| It has been suggested that this article be merged into Nossa Senhora da Graça incident. (Discuss) Proposed since October 2024. |

| This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. Please help improve this article by introducing citations to additional sources. Find sources: "Red Seal ship incident" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2024) |

| Red Seal Ship incident | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Japanese–Portuguese conflicts | |||||||

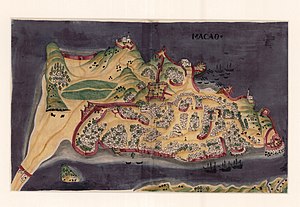

Map of the Macau Peninsula | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | 30-40 or 100 crew | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 magistrate injured Few killed |

27, 50 or 60 killed 50 surrendered Unknown number of ringleaders executed | ||||||

The Red Seal ship incident (マカオの朱印船騒擾事件) was a confrontation in 1608 or 1609 between the Portuguese authorities in Macau and a crew of Japanese sailors aboard a Red Seal Ship belonging to Arima Harunobu.

Background

In 1608, a red seal ship belonging to the Hinoe daimyō Arima Harunobu anchored in Macau after returning from Cambodia, where it had acquired a cargo of agarwood. The ship intended to winter in Macau until the 1609 monsoon season. During this time, the Japanese crew, consisting of 30-40 members, displayed rowdy behavior as they roamed the town. Their actions alarmed the Chinese inhabitants, prompting them to urge the Senate of Macau to take measures against the Japanese. However, the Senate merely advised the Japanese to moderate their behavior and to disguise themselves as Chinese, advice that was ignored.

As the Japanese crew continued their unruly behavior, tensions escalated. The Portuguese authorities, concerned that the Japanese might attempt to seize control of Macau, decided to take a firmer stance. This culminated in a serious brawl on November 30, 1608, during which the Portuguese magistrate, known as the ouvidor, was injured, and some of his retainers were killed. Alarmed by the situation, Captain-major André Pessoa responded with armed reinforcements, forcing the Japanese to take refuge in nearby houses.

Incident

In the wake of the brawl, the Portuguese surrounded the houses where the Japanese had taken refuge. Pessoa offered quarter to those who would surrender, but 27 of the Japanese in the first house refused, leading to their deaths when they were forced out under fire. Meanwhile, the Japanese in a second house, numbering around 50, surrendered after Jesuits intervened, promising them life and freedom. However, Pessoa subsequently had the suspected ringleaders executed while allowing the others to leave Macau after they signed an affidavit absolving the Portuguese of any blame.

Estimates of the Japanese casualties vary, with reports indicating between 27, 50 and 60 were killed during the conflict. The rest were only allowed to board their ships back to Japan after signing a sworn statement accepting full responsibility for the incident and absolving the Portuguese of any blame. The defeated and humiliated Japanese weighed anchor and headed back to Nagasaki.

Aftermath

On May 10, 1609, the Portuguese carrack, known as either Nossa Senhora da Graça or Madre de Deus, departed Macau, carrying a rich cargo intended for the Japanese market. Captain André Pessoa, fearing Dutch piracy due to previous conflicts, accelerated the ship's departure. On June 29, 1609, he landed in Nagasaki, only to face the repercussions of the earlier incident.

The Japanese authorities, notably Arima Harunobu, who was informed of the incident by Japanese survivors, were incensed over the deaths of their compatriots, leading to an investigation into the conflict. Reports reached Tokugawa Ieyasu that painted Pessoa's actions as “the blackest of colors”, however, Ieyasu was hesitant to take drastic action, as it would result in the loss of the silk trade.

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ Boxer 1951, p. 271.

- ^ 榊原英資『榊原英資の成熟戦略』p.116

- ^ Boxer 1979, p. 37.

- ^ Kshetry 2008, p. 49.

- Yamashiro 1989, p. 114.

- ^ Sanz 2017.

- Boxer 1948, p. 53 sfnm error: no target: CITEREFBoxer1948 (help); Boxer 1951, p. 270.

- Boxer 1951, p. 278.

- Boxer 1979, p. 41.

- Boxer 1979, p. 41; Boxer 1948, p. 54 sfnm error: no target: CITEREFBoxer1948 (help).

- Boxer 1951, p. 276.

- Boxer 1951, p. 276-277.

Sources

- Boxer, C. R. (1951). The Christian Century in Japan: 1549–1650. University of California Press. GGKEY:BPN6N93KBJ7.

- Boxer, C. R. (1979) . "The affair of the Madre de Deus". In Moscato, Michael (ed.). Papers on Portuguese, Dutch, and Jesuit Influences in 16th- and 17th-Century Japan: Writings of Charles Ralph Boxer. Washington, D.C.: University Publications of America. pp. 4–94. ISBN 0890932557.

- Sanz, Javier (November 29, 2017). "LA GESTA DEL CAPITÁN PESSOA Y SUS 50 LOBOS DE MAR FRENTE A UN EJÉRCITO DE SAMURÁIS" (in Spanish). Javier Sanz.

- Yamashiro, José (1989). Choque luso no Japão dos séculos XVI e XVII (in Portuguese). IBRASA. ISBN 9788534810685.

- Kshetry, Gopal (2008). Foreigners in Japan: A Historical Perspective. ISBN 9781469102443.

- 1609 in Japan

- Conflicts in 1609

- 1609 in the Portuguese Empire

- Foreign relations of the Tokugawa shogunate

- Japan–Portugal relations

- Naval battles involving Japan

- Naval battles involving Portugal

- Battles involving Japan

- Battles involving Portugal

- Arima clan

- 17th-century military history of Japan

- Portuguese Macau