This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

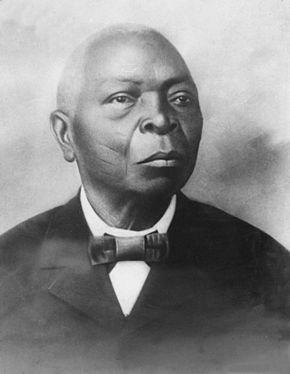

Ño Remigio Herrera Adeshina Obara Meyi (1811/1816 – 1905) was a babalawo (Yoruba priest) recognized for being, along with his mentor Carlos Adé Ño Bí (birth name, Corona), the main successor of the religious system of Ifá in America. Ño Remigio Herrera was perhaps the most famous surviving African in Cuba in the 19th century. Ño, synonymous to "Sir", was a title of distinction, a term of respect and endearment bestowed upon the great native elders of the African "nations" on the island. His name "Adeshina" means "Crown-Opens-The-Way" in Yoruba.

Early life

Herrera was born in Ijesha, in Osun state, in present-day Nigeria. Shortly before being caught by his captors in Africa, and the imminence of his future slavery, Adeshina quickly swallowed the representative basis of orisha Orula or Orunmila to carry with him to his new destination. This ingenious decision, and his impressive display of intelligence on American soil buyers, subsequently constitutes the fundamental line of historical and religious continuity of Ifa diaspora with its African source. Ño Remigio Herrera was sold into slavery in the early 1830s. According to certificates of baptism of the parish church of Nueva Paz, "Remigio Lucumí" was baptized in 1833. "Lucumí" was the nation-name given to the Yoruba in the four-hundred-year-old slave trade. Historians claim that Africans were often subject to three years of "preparation" for baptism, including Spanish language learning to carry out the required catechumens for baptism. Therefore, the probable year of arrival of Adeshina (Corona Gunning) to Cuba was 1830. He labored for twenty years on the giant plantation owned by Don Miguel Antonio Herrera in Nueva Paz, located in the fertile commercial crossroads between three bustling colonial cities: Trinidad, Havana, and Matanzas. He was recognized for his exceptional intelligence and extraordinary gifts and was sent to Havana to attend to his master's business. In Rule, Adeshina cultivated good relations with the Spanish owner of a winery, and met Carlos Adé Ño Bí, a freedman, who had been the butler and personal confidant of the Spanish. Carlos Adé Bí was not only a mentor of Ifa divination to Adeshina, but also subsequently provided the financial resources to pay the price for his freedom around 1850. Ño Carlos Adé Bí Ojuani Boka was a priest of Ifa who negotiated his release before his Spanish master by displaying his skills with the use of Ifa divination tool, okpele or ekuele. He won his freedom after positively impressing two Spanish guests of his master, who were convinced of his outstanding intelligence. Ño Carlos, had a bet with him that if he guessed to them accurately, would buy his freedom from his master, whom they considered particularly insensitive. Ño Carlos guessed exactly making a circular shells of okpele orange and branches of a vine, and the Spaniards avoided a precipitous loss in business and saved their fortunes. Cleverly, using valuable relationships, both took advantage of the security offered them in the winery, and used the back room to "wash" ritually, or "re-consecrating" the representative basis of orisha Orula or Orunmila which the young Adeshina had swallowed in Yorubaland and had subsequently defecated on the boat that had transported him along with other slaves. Despite the training of Ifa that Adeshina Obara meyi had received in Yorubaland, Ño Carlos Adé Bí became his representative on the Cuban soil, and as his "godfather" they both formed a series of race relations and cross-class to ensure the back room of the winery as a ritual space, in a time when the sacred resources of lucumí, temples and his followers were still a critical mass, a significant population in Havana, in the second half of the 1830s.

A man of means

After gaining his freedom around 1850, Adeshina began to engage in urban society in Cuba with growing strength and success. He got married and started a large family that survives today and continued his studies of divination with sages who had preceded him to Cuba. He made his first residence in Matanzas City, known as Cuba's African "Athens." In the mid-1860s, Adeshina lived in Rule, as indicated by the birth of his daughter Josefa Herrera (Pepa Eshu Bí) in 1864 and his son Teodoro Herrera in 1866, evident from their birth and christening certificates. There he founded the Cabildo Yemaya with Ño Filomeno García "Atanda", Ño Juan "lame" and Aña Bí (his future wife), whom he met while living in Matanzas. This period marked the beginning of the life of Adeshina as a man of means, able to support and accommodate the council, first located at home, and later on land Morales Street. He later became a property owner, builder and man of connections and influence as indicated by the census documents of 1881. In this census, it appears that the birth year of Adeshina was in 1811. Moving back and forth along the well-traveled road to the capital, Havana, he built his fortune as a stonemason, cultivated patronage relationships with white professional families, trained countless others in the Lucumí religion, and set down a veritable residence on St. Ciprian Street (later Fresneda) in the Havana seaport village of Regla by the late 1860s. The town takes its name from the Holy Virgin of Regla, whose sanctuary was founded by the Spanish noble Antón Recio, who owned Regla's lands as early as the 1600s. A series of documents from 1900 also reveal the significant price of his home and other property. The house was valued at 115,000 pesos of Spanish gold and also showed rental income from other properties of six silver pesos monthly. Adeshina also owned other landed property unoccupied at Calle Morales (later renamed Street Perdomo) valued at 300 pesos of gold. Its economically independent position suggested by the fact that the mortgage, as seen in the pages 492, No. 32, November 12, 1900; and No. 1600 of the City of Rule, province of Havana, were related to urban properties. As a result of Adeshina's significant social connections, prominent Cuban elites witnessed his marriage on October 26, 1891, including Matanzas Francisca Burlet, a white businessman, a magistrate, a pharmacist and a butler. In the marriage certificate, his birth date is stated as 1816.

Family photograph and later years

The spiritual stature and radiant character of Adeshina was reflected in his oval portrait photograph, probably taken on the occasion of his marriage in 1891. It is the only existing photograph of an African babalawo at the time. He appeared dressed in Western fashion, clad in suits and ties, white-haired, and with three ethnic markings on each cheek. The photograph was taken at a time when hardly an African would be immortalized in a portrait, since they were usually discriminated to be just "filler" pictures as backgrounds of landscapes, or reason for a photo shoot in anthropological literature. His intention to immortalize, perfectly dressed according to the conventions of the late nineteenth century, most likely due to the photograph would have a wider audience to their religious colleagues, godchildren or religious descendants and family in general. Other versions of the halftone photography portrait suggested that Adeshina was reproduced in the press. His sympathetic portrait appeared in Cuban newspapers, a rare occurrence for Africans. Adeshina Obara was multiply represented due to his social status, as a figure for posterity. From the time of his death in 1905 (in Havana), Adeshina became a respected and revered ancestor, present in the homes of his descendants, and rituals throughout Cuban places. Around 1980, the African presence in Rule was symbolized by placing his portrait at the entrance of the Museum of Regla.

Ño Remigio Herrera among the people

Remigio Herrera was so revered in Regla, when people met him on the street, they saluted him by genuflecting before him and kissing his hand. A day in the fishing town of Regla, Havana, where he established a large family, a woman came to him with tears of despair: "My husband has been on a boat and I don't know if he will ever come back." He had been away at sea for many days without any knowledge of his whereabout. Ño Remigio was moved to pity by the lady, he went to consult his Ifa oracle, made a series of prayers and signs in the dust of Orunmila, then took the woman and went to the docks. On the site, Ño Remigio made a series of liturgical prayers, and blew dust into the ocean. In the next ship sailing in the great port of Rule was her husband. He had returned.

References

- Lisandro Perez; Uva De Aragon (1 Feb 2004). Cuban Studies. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822970804.

- Torin Alexander; Stephen C. Finley, Torin Alexander; Anthony B. Pinn (2009). African American Religious Cultures, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 352. ISBN 9781576074701.

- Frank Baba Eyiogbe (2015). Babalawo, Santeria's High Priests: Fathers of the Secrets in Afro-Cuban Ifa. Llewellyn Worldwide. ISBN 9780738744087.

- ^ David H. Brown (15 October 2003). Santeria Enthroned: Art, Ritual, and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion The Chicago Series on Sexuality, History, and Society Series. University of Chicago Press, 2003. ISBN 9780226076102.

- Stephan Palmié (2013). The Cooking of History: How Not to Study Afro-Cuban Religion. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226019420.

- "Yoruba priests issued Letter of the Year in Cuba" (in Spanish). Escambray. January 1, 2015.

- 1810s births

- 1905 deaths

- Cuban Santeríans

- Babalawos

- Yoruba slaves

- Freedmen

- People from Ilesha

- 19th-century Nigerian people

- Nigerian emigrants to Cuba

- Cuban people of Yoruba descent

- 19th-century religious leaders

- Psychics

- Cuban religious leaders

- 19th-century Cuban people

- Cuban slaves

- Cuban landowners

- 19th-century landowners