| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Glorious Revolution" Spain – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (August 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Spanish Revolution of 1868 Glorious Revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Revolution of 1868 "La Gloriosa", allegorical cartoon of 1874 published in the magazine La Flaca | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

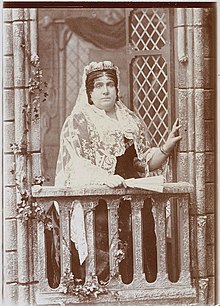

The Glorious Revolution (Spanish: la Gloriosa or la Septembrina) took place in Spain in 1868, resulting in the deposition of Queen Isabella II. The success of the revolution marked the beginning of the Sexenio Democrático with the installment of a provisional government.

Background

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2014) |

Leading up to the Glorious Revolution, there had been numerous failed attempts to overthrow the unpopular Queen Isabella, most notably in 1854 and 1861. An 1866 rebellion led by General Juan Prim and a revolt of the sergeants at San Gil barracks, in Madrid, sent a signal to Spanish liberals and republicans that there was serious unrest that could be harnessed if it were properly led. Liberals and republican exiles abroad made agreements at Ostend in 1866 and Brussels in 1867. These agreements laid the framework for a major uprising, this time not merely to replace the Prime Minister with a Liberal, but to overthrow Queen Isabella, whom Spanish liberals and republicans began to see as the source of Spain's difficulties.

Her continual vacillation between liberal and conservative quarters had, by 1868, outraged the moderates, the progressives, and the members of the Unión Liberal. An opposition to her government had developed that crossed party lines. Leopoldo O'Donnell's death in 1867 caused the Unión Liberal to unravel; many of its supporters, who had crossed party lines to create the party initially, joined the growing movement to overthrow Isabella in favor of a more effective regime.

Revolution

In September 1868, naval forces under admiral Juan Bautista Topete mutinied in Cadiz. This was the same city where a half-century before, Rafael del Riego had launched his coup against Isabella's father, Ferdinand VII.

When the generals Prim and Francisco Serrano denounced the government, much of the army defected to the revolutionary generals on their arrival in Spain. The queen made a brief show of force at the Battle of Alcolea, where her loyal moderado generals under Manuel Pavia were defeated by General Serrano.

In 1868, Queen Isabella crossed into France and retired from Spanish politics. She lived there in exile, at the Palacio Castilla in Paris, until her death in 1904.

Aftermath

The revolutionary spirit that had just overthrown the Spanish government lacked direction; the coalition of liberals, moderates, and republicans were faced with the incredible task of creating a government that would suit them better than had Isabella. Control of the government passed to Francisco Serrano, an architect of the revolution against Baldomero Espartero's dictatorship. The Cortes initially rejected the notion of a republic; Serrano was named regent while a search was launched for a suitable monarch to lead the country. In 1869, the Cortes wrote and promulgated a liberal constitution, the first such constitution in Spain since 1812.

The search for a suitable king proved to be problematic for the Cortes. The republicans were mostly willing to accept a monarch if he was capable and abided by a constitution. Prim, a perennial rebel against the Isabelline governments, was named regent in 1869. The aged Espartero was brought up as an option, still having considerable sway among the progressives; even after he rejected the notion of being named king, he received eight votes for his coronation in the final tally. Many proposed Isabella's young son Alfonso (the future Alfonso XII of Spain), but others thought that he would be dominated by his mother and inherit her flaws. Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg, the former regent of neighboring Portugal, was sometimes mentioned as a possibility. Politicians feared that a nomination offered to Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen would trigger a Franco-Prussian War.

In August 1870, they selected an Italian prince, Amadeo of Savoy. The younger son of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy, Amadeo had less of the troublesome political baggage that a German or French claimant would bring, and his liberal credentials were strong. He was elected King as Amadeo I of Spain on November 3, 1870.

He landed in Cartagena on November 27, the same day that Juan Prim was assassinated while leaving the Cortes. Amadeo swore upon the general's corpse that he would uphold Spain's constitution. He lasted two years, after which the parties formed the first Spanish Republic. That in turn lasted two years. No political force was willing to restore Isabella; instead, in 1875 the Cortes proclaimed Isabella's son as King Alfonso XII.

See also

References

- Thomson, Guy (2009). The Birth of Modern Politics in Spain: Democracy, Association and Revolution, 1854-75. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 9780230248564.