| Republic of the Rifجمهورية الريف (Arabic) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1921–1926 | |||||||||

Flag

Flag

Coat of arms

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

| Anthem: National Anthem of the Republic of the Rif | |||||||||

Territory of Spanish Morocco under control of the Rif Republic. Territory of Spanish Morocco under control of the Rif Republic. | |||||||||

| Capital | Ajdir | ||||||||

| Official languages | Arabic | ||||||||

| Common languages | Jebli Arabic, Tarifit | ||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Confederal presidential republic under a military dictatorship | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

| • 1921–1926 | Abd el-Krim | ||||||||

| Vice President | |||||||||

| • 1921–1926 | Hajj Hatmi | ||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | ||||||||

| • Established | 18 September 1921 | ||||||||

| • Rif War | 8 June 1921 | ||||||||

| • Disestablished | 27 May 1926 | ||||||||

| Currency | Rif Republic Riffan | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Morocco | ||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Morocco |

|

| Prehistory |

|

Classical to Late Antiquity (8th century BC – 7th century AD) |

|

Early Islamic (8th–10th century AD) |

|

Territorial fragmentation (10th–11th century AD) |

|

Empire (beginning 11th century AD) other political entities |

|

Decline (beginning 19th century AD) |

|

Protectorate (1912–56) |

|

Modern (1956–present) |

Related topics

|

The Republic of the Rif (Arabic: جمهورية الريف Jumhūriyyatu r-Rīf) was a confederate republic in the Rif, Morocco, that existed between 1921 and 1926. It was created in September 1921, when a coalition of Rifians and Jebala led by Abd el-Krim revolted in the Rif War against the Spanish protectorate in Morocco. The French would intervene on the side of Spain in the later stages of the conflict. A protracted struggle for independence killed many Rifians and Spanish–French soldiers, and witnessed the use of chemical weapons by the Spanish army—their first widespread deployment since the end of the World War I. The eventual Spanish–French victory was owed to the technological and manpower advantages despite their lack of morale and coherence. Following the war's end, the Republic was ultimately dissolved in 1926.

History

Background

See also: Morocco, French protectorate in Morocco, and French conquest of MoroccoThe French and Spanish empires both colonized Morocco, and in 1912 the Treaty Between France and Spain Regarding Morocco established Spanish and French protectorates there.

France's general approach to governing the protectorate of Morocco was a policy of indirect rule, where they co-opted existing governance systems to control the protectorate. Specifically, the Moroccan elite and the sultans of Morocco were both left in control while being strongly influenced by the French government.

French and Spanish colonialism in Morocco was discriminatory against the native Rifians and Sahrawis and was highly detrimental to the Moroccan economy. Moroccans were treated as second-class citizens and discriminated against in all aspects of colonial life.

Infrastructure was discriminatory in colonial Morocco. The French colonial government built 36.5 kilometers of sewers in the new neighborhoods created to accommodate new French settlers, while only 4.3 kilometers of sewers were built in indigenous Moroccan communities. Additionally, land in Morocco was far more expensive for Moroccans than for French settlers. For example, while the average Moroccan had a plot of land 50 times smaller than their French settler counterparts, Moroccans were forced to pay 24% more per hectare. Moroccans were additionally prohibited from buying land from French settlers.

Colonial Morocco's economy was designed to benefit French businesses at the detriment of Moroccan laborers. Morocco was forced to import all of its goods from France despite higher costs. Additionally, improvements to agriculture and irrigation systems in Morocco exclusively benefited colonial agriculturalists while leaving Moroccan farms at a technological disadvantage. It is estimated that French colonial policies resulted in 95% of Morocco's trade deficit by 1950.

Rif War

Main article: Rif WarFollowing the allowance of its interests and recognition of its influence in northern Morocco through the 1904 Entente Cordiale, 1906 Algeciras Conference and 1907 Pact of Cartagena, Restoration-era Spain occupied Ras Kebdana, a town near the Moulouya River, in March 1908 and launched the Melillan and Kert campaigns against the Riffian tribes between 1909 and 1912. In June 1911, Spanish troops occupied Larache and Ksar el-Kebir.

The Moroccan independence president Abd el-Krim (1882–1963) organized an armed revolution, the Rif War, against the Spanish and French colonial control of Morocco. The Spanish had faced unrest off and on from the 1890s, but in 1921 Spanish colonial troops were massacred at the Battle of Annual. Abd el-Krim founded an independent Republic, the Rif Republic, which operated until 1927 but had no formal international recognition.

France and Spain did not recognize the Republic and collaborated to destroy it. They sent in 200,000 soldiers, forcing Abd el-Krim to surrender in 1926. He was exiled in the Pacific until 1947. Morocco became quiet, and in 1936 became the base from which Francisco Franco launched the fascist coup of July 1936.

In 1921, local Rifians, under the leadership of Abd el-Krim, crushed a Spanish offensive led by General Manuel Fernández Silvestre at the Battle of Annual, and soon after declared the creation of an independent republic on 18 September 1921. The republic was formally constituted in 1923, with Abd el-Krim as head of state, and Ben Hajj Hatmi as prime minister.

Abd el-Krim handed the Spanish numerous defeats, driving them back to coastal outposts. With the war ongoing, he sent diplomatic representatives to London and Paris, in an ultimately futile attempt to establish legitimate diplomatic relations with other European powers.

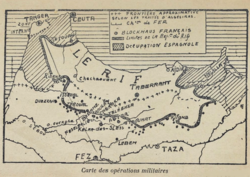

In late 1925, the French and Spanish created a joint task force of 500,000 men, supported by tanks and aircraft. After 1923, the Spanish employed the use of chemical weapons imported from Germany. The Republic was dissolved by Spanish and French occupation forces on 27 May 1926, but many Rif guerrillas continued to fight until 1927.

In April 1925, Abd el-Krim proclaimed the independent Republic in the Rif region of Spanish Morocco. He advanced south into French Morocco, defeating French forces and threatening the capital, Fes. The resident-general, Hubert Lyautey, was replaced as military commander by Philippe Pétain on 3 September 1925. On 11 October 1925, Théodore Steeg replaced Lyautey as resident-general with the mandate of restoring peace and making the transition from military to civilian government. Lyautey received very little recognition for his achievement in securing Morocco as a colony. Steeg would have been willing to give autonomy to the people of the Rif, but was overruled by the army.

Abd el-Krim surrendered to Philippe Pétain on 26 May 1926 and was deported to Réunion in the Indian Ocean, where he was held until 1947. Théodore Steeg said Abd el-Krim was a great leader and national and folk hero, but Abd el-Krim wanted "neither exalted nor humiliated, but in time forgotten."

See also

References

- Engle, Shirley H. (1964). New Perspectives in World History. National Council for the Social Studies. p. 439.

Indeed, Abdelkrim, recognizing the inherent weakness of the short-lived Berber nation, sought to bolster his strength by making Arabic the language of his government, and evolving Arab administrative arrangements and rules of procedure.

- Day, Richard B.; Gaido, Daniel (2011-11-25). Discovering Imperialism: Social Democracy to World War I. BRILL. p. 549. ISBN 978-9004201569. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- Wyrtzen, Jonathan (2016-02-19). Making Morocco: Colonial Intervention and the Politics of Identity. Cornell University Press. p. 183. ISBN 9781501704246. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- Hall, John G.; Publishing, Chelsea House (2002). North Africa. Infobase Publishing. p. 62. ISBN 9780791057469. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ "Morocco - Decline of traditional government (1830–1912) | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

- ^ Bennis, Samir (1 March 2023). "What Moroccan Schools Do Not Teach About the Toxic Legacy of France's Protectorate". moroccoworldnews.com. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, p. 121.

- "Périple autour des îles Jaâfarines". Le 360 Français (in French). Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- León Rojas 2018, p. 50.

- Ramos Oliver (2013), p. 176.

- Clark 2013, p. 205.

- Daudin, Pascal (13 December 2022). "The Rif War: A forgotten war?". International Review of the Red Cross. 105 (923): 920. doi:10.1017/S1816383122001023. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- Alexander Mikaberidze (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 15. ISBN 978-1598843361.

- David S. Woolman, Rebels in the Rif: Abd El Krim and the Rif Rebellion (Stanford University Press, 1968), p. 96

- "Morocco - The Spanish Zone". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-11.

- Slavin, David H. (Jan 1991), "The French Left and the Rif War, 1924–25: Racism and the Limits of Internationalism", Journal of Contemporary History, 26 (1): 5–32, doi:10.1177/002200949102600101, JSTOR 260628, S2CID 162339547

- Rudibert Kunz: "Con ayuda del más dañino de todos los gases" – Der Gaskrieg gegen die Rif-Kabylen in Spanisch-Marokko in Irmtrud Wojak/Susanne Meinl (eds.): Völkermord und Kriegsverbrechen in der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts, Frankfurt/Main 2004, pp. 153–191 (here: 169–185).

- "Abd el-Krim – Adb el-Krim during the Rif War". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-11.

- Lepage 2008, p. 125.

- Lepage 2008, p. 126.

- Griffiths 2011, p. 111.

- Jolly 1977.

- Woolman 1968, p. 195.

- Griffiths 2011, p. 113.

- Ansprenger 1989, pp. 88–89.

- Woolman 1968, p. 208.

Sources

- Ansprenger, Franz (1989). The Dissolution of the Colonial Empires. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-03143-1. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- Clark, Christopher (19 March 2013). The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-114665-7.

- Griffiths, Richard (2011-05-19). Marshal Pétain. Faber & Faber. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-571-27909-8. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- Jolly, Jean (1977). "STEEG (JULES, JOSEPH, Théodore)". Dictionnaire des parlementaires français: notices biographiques sur les ministres, sénateurs et députés français de 1889 à 1940 (in French). Presses universitaires de France. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

- León Rojas, José (2018). "Tarifa y las Campañas de Marruecos (1909-1927)". Aljaranda. 1 (92). Tarifa: Ayuntamiento de Tarifa: 47–66. ISSN 1130-7986.

- Lepage, Jean-Denis G.G. (2008). The French Foreign Legion: An Illustrated History. McFarland. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-7864-6253-7. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- Ramos Oliver, Francisco (2013). "Las guerras de Marruecos" (PDF). Entemu. Gijón: UNED Centro Asociado de Asturias: 165–185. ISBN 978-84-88642-16-5. ISSN 1130-314X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-08-27.

- Saro Gandarillas, Francisco (1993). "Los orígenes de la Campaña del Rif de 1909". Aldaba (22). Melilla: UNED: 97–130. doi:10.5944/aldaba.22.1993.20298 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISSN 0213-7925. Archived from the original on 28 October 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Woolman, David S. (1968). Rebels in the Rif: Abd El Krim and the Rif Rebellion. Stanford University Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-8047-0664-3. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

35°12′N 3°55′W / 35.200°N 3.917°W / 35.200; -3.917

Categories:- 1921 establishments in Africa

- 1926 disestablishments

- 1920s in Morocco

- Rif

- Former countries in Africa

- Former republics

- Republicanism in Morocco

- Berber history

- Separatism in Morocco

- Former unrecognized countries

- States and territories established in 1921

- States and territories disestablished in 1926

- Morocco–Spain relations

- Former countries of the interwar period

- Islamic states

- Former countries

- Rif War