This article is about the 1818 steamship Savannah. For other uses of the term, see Savannah (disambiguation).

Savannah Savannah

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Savannah |

| Namesake | Savannah, Georgia |

| Owner | Scarbrough & Isaacs |

| Builder | Fickett & Crockett |

| Cost | $50,000 ($774,239 today) |

| Launched | August 22, 1818 |

| Completed | 1818 |

| Maiden voyage | May 24, 1819 |

| In service | March 28, 1819 |

| Out of service | November 5, 1821 |

| Fate | Wrecked at Long Island, November 5, 1821 |

| Notes | First steam-powered vessel to cross the Atlantic, May 24 – June 20, 1819 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Hybrid sailing ship/sidewheel steamer |

| Tons burthen | 319 74/94 |

| Length | 98 ft 6 in (30.02 m) p.p. |

| Beam | 25 ft 10 in (7.87 m) |

| Depth of hold | 14 ft 2 in (4.32 m) |

| Installed power | 90 hp (67 kW) |

| Propulsion | Sails, plus 1 × inclined direct-acting 90 hp (67 kW) steam engine driving 2 × 16 ft (4.9 m) paddlewheels |

| Sail plan | Ship-rigged |

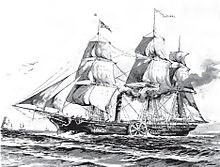

SS Savannah was an American hybrid sailing ship/sidewheel steamer built in 1818. She was the first steamship to cross the Atlantic Ocean, transiting mainly under sail power from May to June 1819. In spite of this historic voyage, the great space taken up by her large engine and its fuel at the expense of cargo, and the public's anxiety over embracing her revolutionary steam power, kept Savannah from being a commercial success as a steamship. Originally laid down as a sailing packet, she was, following a severe and unrelated reversal of the financial fortunes of her owners, converted back into a sailing ship shortly after returning from Europe.

Savannah was wrecked off Long Island, New York in 1821. No other American-owned steamship would cross the Atlantic for almost thirty years after Savannah's pioneering voyage. Two British sidewheel steamships, Brunel's SS Great Western and Menzies' SS Sirius, raced to New York in 1838, both voyages being made under steam power alone.

Development

Savannah was laid down as a sailing packet at the New York shipyard of Fickett & Crockett. While the ship was still on the slipway, Captain Moses Rogers, with the financial backing of the Savannah Steam Ship Company, purchased the vessel in order to convert it to an auxiliary steamship and gain the prestige of inaugurating the world's first transatlantic steamship service.

Savannah was fitted with an auxiliary steam engine and paddlewheels in addition to her sails. Moses Rogers himself supervised the installation of the machinery, while his distant cousin, and later brother-in-law, Stevens Rogers oversaw installation of the ship's rigging and sails.

Since Savannah crossed the Atlantic mainly under sail power some sources contend that the first transatlantic steamship was the SS Royal William, crossing in 1833. It used sail only during boiler maintenance. Another claimant is the British-built Dutch-owned Curaçao, which used steam power for several days when crossing the Atlantic both ways in 1827.

Description

The Allaire Iron Works of New York supplied Savannah's engine cylinder, while the rest of the engine components and running gear were manufactured by the Speedwell Ironworks of New Jersey. The 90-horsepower low-pressure engine was of the inclined direct-acting type, with a single 40-inch-diameter (100 cm) cylinder and a 5-foot stroke. Savannah's engine and machinery were unusually large for their time, and after the ship's launch, Moses Rogers had difficulty locating a suitable boiler, rejecting several before settling on a copper model by boiler specialist Daniel Dod. The ship's wrought-iron paddlewheels were 16 feet in diameter with eight buckets per wheel. For fuel, the vessel carried 75 tons of coal and 25 cords of wood.

As the ship was too small to carry much fuel, the engine was intended only for use in calm weather, when the sails were unable to provide a speed of at least four knots. In order to reduce drag and avoid damage when the engine was not in use, the paddlewheel buckets were linked by chains instead of bars, enabling the wheels to be folded up like fans and stored on deck. Similarly, the paddlewheel guards were made of canvas stretched over a metal frame which could also be packed away when not required. The whole process of retracting the wheels and guards took no more than about 15 minutes. Savannah is the only known ship to have been fitted with retractable paddlewheels.

Savannah's hull and rigging were constructed under the direction of Captain Stevens Rogers, who later became the ship's sailing master. The ship was full rigged like a normal sailing ship, excepting the absence of royal-masts and royals. Contemporary engravings suggest that Savannah's mainmast was set further astern than in normal sailing ships, in order to accommodate the engine and boiler.

Interior

Savannah was fitted with 32 passenger berths, with two berths in each of the 16 state rooms. The women's quarters were reported to be "entirely distinct" from the men's. Three fully furnished saloons were also provided, complete with imported carpets, curtains and hangings, and decorated with mirrors. The state rooms were large and comfortable and the interior has been described as more closely resembling a pleasure yacht than a steam packet.

Early service

When it became known that Savannah was intended for transatlantic service, the vessel was quickly dubbed a "steam coffin" in New York and Moses Rogers was unable to hire a crew there. Stevens Rogers then traveled to New London, Connecticut, his hometown, where his reputation was well established, and he could find seamen prepared to serve on the vessel.

Savannah conducted a successful trial of approximately two hours duration in New York Harbor to test her engine on Monday March 22, 1819. On Sunday, March 28 at 10 a.m., Savannah sailed from New York to her operating port of Savannah, Georgia. The following morning the ship got steam up for the first time at 11 a.m., but the engine was in use only half an hour before rough weather persuaded the captain to stow the paddlewheels and revert to sail power once again. The ship reached her destination April 6, having employed the engines for a total of 41½ hours during the 207-hour voyage. In spite of arriving at 4 a.m., a large crowd was on hand to welcome the vessel into port.

Presidential excursion

A few days after Savannah's arrival in Savannah Harbor, the President of the United States, James Monroe, visited the nearby city of Charleston, South Carolina as part of an extended tour of inspection of arsenals, fortifications and public works along the East coast of the United States. On hearing of the visit, Savannah's principal owner William Scarbrough instructed Rogers to sail north to Charleston to invite the President to return to the city of Savannah aboard the steamship.

Savannah departed under steam for Charleston on April 14, and after an overnight stopover at Tybee Island Light, arrived at Charleston two days later. Scarbrough's invitation was sent, but as the locals objected to the President leaving South Carolina on a Georgian vessel, he pledged to visit the ship at a later date. On April 30, Savannah made steam for her home port once again, arriving there the following day after a 27-hour voyage.

On May 7 and 8 Savannah took on coal, and on May 11, President Monroe made good on his promise and arrived to take an excursion on the ship. After the President and his entourage had been welcomed aboard, Savannah departed under steam around 8 a.m. for Tybee Lighthouse, arriving there at 10:30 a.m., and departing for town again at 11. Monroe dined on board, expressing enthusiasm to the ship's owner, Mr. Scarbrough, over the prospect of an American vessel inaugurating the world's first transatlantic steamship service. The President was also greatly impressed by Savannah's machinery, and invited Scarbrough to bring the ship to Washington after her transatlantic crossing so that Congress could inspect the vessel with a view to purchasing her for use as a cruiser against Cuban pirates.

Historic transatlantic voyage

In the days following Monroe's departure, Savannah's crew, with Captain Moses Rogers in command and Stevens Rogers as sailing master, made their final preparations for the Atlantic crossing. On May 15, the ship broke free from her moorings during a squall, but apart from slight damage to her paddles, the ship was unharmed.

Savannah's owners made every effort to secure passengers and freight for the voyage, but no-one was willing to risk lives or property aboard such a novel vessel. On May 19, a late advertisement appeared in the local paper announcing the date of departure as May 20. In the event, Savannah's departure was delayed for two days after one of her crew returned to the vessel in a highly inebriated state, fell off the gangplank and drowned. In spite of this delay however, still no passengers came forward, and the ship would make her historic voyage purely in an experimental capacity.

The voyage

After leaving Savannah Harbor on May 22 and lingering at Tybee Lighthouse for several hours, Savannah commenced her historic voyage at 5 a.m. on Monday May 24, 1819, under both steam and sail bound for Liverpool, England. At around 8 a.m. the same day, the paddlewheels were stowed for the first time and the ship proceeded under sail. Several days later, on May 29, the schooner Contract spied a vessel "with volumes of smoke issuing", and assuming it was a ship on fire, pursued it for several hours but was unable to catch up. Contract's skipper eventually concluded the smoking vessel must be a steamboat crossing for Europe, exciting his admiration as "a proud monument of Yankee skill and enterprise".

On June 2, Savannah, sailing at a speed of 9 or 10 knots, passed the sailing ship Pluto. After being informed by Captain Rogers that his novel vessel was functioning "remarkably well", the crew of Pluto gave Savannah three cheers, as "the happiest effort of mechanical genius that ever sailed the western sea." Savannah's next recorded encounter was not until June 19, off the coast of Ireland with the cutter HMS Kite, which made the same mistake as Contract three weeks earlier and chased the steamship for several hours believing it to be a sailing vessel on fire. Unable to catch the ship, Kite eventually fired several warning shots, and Captain Rogers brought his vessel to a halt, whereupon Kite caught up and its commander asked permission to inspect the ship. Permission was granted, and the British sailors are said to have been "much gratified" by the satisfaction of their curiosity.

On June 18, Savannah was becalmed off Cork after running out of fuel for her engine, but by June 20, the ship had made her way to Liverpool. Hundreds of boats came out to greet the unusual vessel, including a British sloop-of-war, an officer from whom hailed Savannah's sailing master Stevens Rogers, who happened to be on deck. The New London Gazette of Connecticut later reported the encounter in the following terms:

The officer of the boat asked , "Where is your master?" to which he gave the laconic reply, "I have no master, sir". "Where's your captain then?" "He's below; do you wish to see him?" "I do, sir." The captain, who was then below, on being called, asked what he wanted, to which he answered, "Why do you wear that penant, sir?" "Because my country allows me to, sir." "My commander thinks it was done to insult him, and if you don't take it down he will send a force to do it." Captain Rogers then exclaimed to the engineer, "Get the hot-water engine ready." Although there was no such machine on board the vessel, it had the desired effect, and John Bull was glad to paddle off as fast as possible.

On approaching the city, Savannah was cheered by crowds thronging the piers and the roofs of houses. The ship made anchor at 6 p.m. The voyage had lasted 29 days and 11 hours, during which time the vessel had employed her engine for a total of 80 hours, about 11% of the time.

At Liverpool

During Savannah's stay at Liverpool, the ship was visited by thousands of people from all walks of life, including officers of the army and navy and other "persons of rank and influence." Perhaps reflecting the suspicion with which both nations still regarded one another after the recent War of 1812, some suspected the ship of planning to rescue Napoleon Bonaparte from prison on the island of St. Helena; his brother Jerome had recently offered a large reward for such a service.

Savannah remained at Liverpool for 25 days, while the crew scraped and repainted the ship, tested the engine, and replenished fuel and supplies. On July 21 the ship departed Liverpool bound for St. Petersburg in Russia.

Sweden

Savannah reached Elsinore (Helsingor), Denmark, on August 9, where she remained in quarantine for five days. On the 14th the ship sailed on to Stockholm, Sweden, thus becoming the first steamship to enter the Baltic Sea.

Savannah arrived at Stockholm on August 22, and on the 28th was visited by the Prince of Sweden and Norway. On September 1, an excursion on board the ship around the local islands was arranged, which was attended by the American and other ambassadors, nobles and prominent citizens. While in port at Stockholm, the Swedish government offered to purchase the vessel, but the terms were not attractive enough for Moses Rogers and he rejected the offer. Before leaving, the King of Sweden, Charles XIV John, presented Rogers with the gift of a stone and muller. On September 5, Savannah departed for Kronstadt, Russia, arriving there on the 9th.

Russia

At Kronstadt, the Emperor of Russia came aboard Savannah and presented Captain Rogers with gifts of a gold watch and two iron chairs. From Kronstadt, Rogers sailed on to St. Petersburg, arriving there September 13. During the journey from Liverpool to St. Petersburg, Savannah's engine had its most frequent use, being employed for a total of 241 hours.

At St. Petersburg, the American ambassador to Russia extended an invitation to a number of prominent citizens to visit the ship. On September 18, 21 and 23, Savannah made several excursions under steam in the waters off St. Petersburg, with members of the Russian royal family and other noblemen, as well as army and navy officers aboard. During the ship's stay at St. Petersburg, the Russian government also offered to purchase the vessel, but again the terms were not attractive enough for Moses Rogers to accept.

On September 27 and 28, Savannah was occupied in taking on coal and stores for her return journey to the United States. Before leaving, Lord Lynedoch of Scotland, who had travelled on board Savannah from Stockholm to St. Peterburg, presented Captain Moses Rogers and Sailing Master Stevens Rogers with a solid silver coffee urn and a gold snuffbox, respectively.

Homeward crossing

On September 29, Savannah sailed for Kronstadt on the first leg of her journey home. After experiencing several days of rough weather while at Kronstadt, during which the ship lost an anchor and hawser, Savannah left Kronstadt under steam on October 10 bound for Copenhagen, arriving on the 17th, continuing on to Helsingor to pay the Baltic exit toll, then stopping at Arendal, Norway, to wait out bad weather before heading out to open sea and her homeward crossing of the Atlantic. The ship experienced gales and rough seas almost all the way back to the United States, and the engine was not employed again until reaching home waters, the crossing having taken 40 days. Savannah steamed up the Savannah River and arrived safely back at her home port at 10 a.m., November 30, six months and eight days from the date of her departure.

Later history

Savannah remained at her home port until December 3, when she set sail for Washington, D.C., arriving there on the 16th. In January 1820, a great fire swept through the city of Savannah, doing severe damage to the business district. The owners of the Savannah, William Scarbrough and his partners, suffered losses in the fire and were forced to sell the ship.

Savannah's engine was removed and resold for the sum of $1,600 to the Allaire Iron Works, which had originally built the engine cylinder. The cylinder was preserved by the proprietor of the Allaire Works, James P. Allaire, and was later displayed at the New York Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1856. After removal of the engine, the ship was used as a sailing packet, operating between New York and Savannah, Georgia, until running aground along the south shore of Long Island on November 5, 1821, and subsequently breaking up.

Savannah had proven that a steamship was capable of crossing the ocean, but the public was not yet prepared to trust such means of conveyance on the open sea, and the large amount of space taken up by the engine and its fuel made the ship uneconomic in any case. It would be almost another 20 years before steamships began making regular crossings of the Atlantic, and another American-owned steamship would not do so until 1847, almost 30 years later.

The 'Savannah' is portrayed on a 3¢ US commemorative stamp (Scott #923) issued on May 22, 1944.

In October 2022, a roughly 13-foot-square piece of weather-beaten wood flotsam washed up off Fire Island after Tropical Storm Ian. Experts say it is likely part of the SS Savannah. Evidence includes the 1-to-1.3-inch wooden pegs holding the wreckage's planks together, consistent with a 100-foot vessel; the Savannah was 98 feet, 6 inches long. The wreckage's iron spikes suggest a ship built around 1820; the Savannah was built in 1818. The piece of wreckage is now in the custody of the Fire Island Lighthouse Preservation Society, which will work with National Park Service officials to identify the wreckage and put it on public display.

Honors and commemorations

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Chapelle, Howard I., "The Pioneer Steamship Savannah: A Study for a Scale Model", Bulletin – United States National Museum 228 (1963), p. 64. According to this source, these measurements are from the ship's register.

- ^ Morrison 1903, p. 407.

- "Oceangoing Steamships". Information Please. 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- Smithsonian, pp. 617–618.

- ^ Morrison 1903, p. 406.

- Swann, p. 5.

- ^ Smithsonian, p. 618.

- Stanton, p. 27.

- Smithsonian, p. 629.

- ^ Smithsonian, p. 622.

- Charleston Courier, April 17, 1819; quoted in Frank O. Braynard, S.S. Savannah the Elegant Steam Ship (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1963; reprint, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1988), 66 (page citations are to the reprint edition).

- Smithsonian, pp. 622–630.

- Smithsonian, pp. 630–631.

- Smithsonian, pp. 631–632.

- Smithsonian, p. 632.

- ^ Smithsonian, p. 627.

- Smithsonian, pp. 632–633.

- Smithsonian, p. 628.

- Smithsonian, p. 634.

- Smithsonian, pp. 624, 634–635.

- Smithsonian, p. 624.

- ^ Smithsonian, pp. 628, 634–636.

- Smithsonian, pp. 635–636.

- ^ Smithsonian, p. 636.

- Morrison 1903, p. 408.

- "Piece of New York flotsam may be part of 200-year-old shipwreck SS Savannah". The Guardian. February 25, 2023. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023.

References

- Braynard, Frank O. S.S. Savannah the Elegant Steam Ship (Reprint ed.). New York: Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-25750-9. Retrieved November 25, 2024.

- Busch, John Laurence (2010). Steam Coffin – Captain Moses Rogers and The Steamship Savannah Break the Barrier. Hodos Historia LLC. ISBN 9781893616004.

- Morrison, John Harrison (1903). History Of American Steam Navigation. New York: Stephen Daye Press. Retrieved November 25, 2024.

- Morrison, John Harrison (1909). History of New York Ship Yards. New York: Wm. F. Sametz & Co. Retrieved November 26, 2024.

- Smithsonian Institution (1891): "Log Book of the Savannah", from Report of the U.S. National Museum During the Year Ending June 30, 1890, Government Printing Office, Washington.

- Stanton, Samuel Ward (1895): American Steam Vessels, Smith & Stanton, New York, pp. 26–27.

- Swann, Leonard Alexander Jr. (1965): John Roach, Maritime Entrepreneur: the Years as Naval Contractor 1862–1886 — United States Naval Institute (reprinted 1980 by Ayer Publishing, ISBN 978-0-405-13078-6).

| Shipwrecks and maritime incidents in 1821 | |

|---|---|

| Shipwrecks |

|

| Other incidents |

|

| 1820 | |