| Schenectady massacre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the King William's War | |||||||

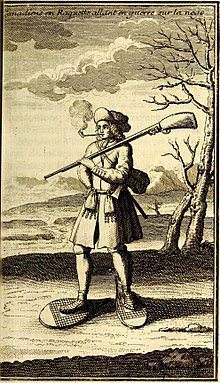

A French infantryman of the period | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Kahnawake Algonquin |

Mohawk | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

114 regulars and militia 96 Indians | 110–120 settlers and Indians | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None |

60 killed 27 captured | ||||||

| Nine Years' War: North America | |

|---|---|

|

The Schenectady massacre was an attack against the colonial settlement of Schenectady in the English Province of New York on February 8, 1690. A raiding party of 114 French soldiers and militiamen, accompanied by 96 allied Mohawk and Algonquin warriors, attacked the unguarded community, destroying most of the homes, and killing or capturing most of its inhabitants. Sixty residents were killed, including 11 Black slaves. About 60 residents were spared, including 20 Mohawk.

Of the non-Mohawk survivors, 27 were taken captive, including five Africans. Three captives were later redeemed; another two men returned to the village after three and 11 years with the Mohawk, respectively. The remainder of the surviving captives were dragged through the snow, tied to horses, and left hungry for weeks before arriving in a Mohawk town north of Montreal. Those who survived were fed and clothed by Mohawk families and began new lives as members of the Mohawk nation.

The French raid was in retaliation for the Lachine massacre, an attack by Iroquois forces on a village in New France. These skirmishes were related both to the Beaver Wars and the French struggle with the English for control of the fur trade in North America, as well as to King William's War between France and England. By this time, the French considered most of the Iroquois to be allied with the English colony of New York, and hoped to detach them while reducing English influence in North America.

Background

In much of the late 17th century, the Iroquois and the colonists of New France engaged in a protracted struggle for control of the economically important North American fur trade, known as the Beaver Wars. The Iroquois also fought other Native American nations to control the lucrative trade with the French. In August 1689, the Iroquois launched one of their most devastating raids against the French frontier community of Lachine. This attack occurred after France and England had declared war on each other but before the news had reached North America.

New France's governor, Louis de Buade de Frontenac, organized an expedition from Montreal to attack English outposts to the south, as retaliation for English support of the Iroquois and as a general expansion of the war against the northernmost English colonies. He intended to intimidate the Iroquois and try to cut them off from their trade with the English. The expedition was one of three directed at isolated northern and western settlements, and it was originally directed against Fort Orange (present day Albany).

It consisted of 114 French Canadians, mostly frontier-savvy coureurs de bois but also some marines, 80 Sault, and 16 Algonquin warriors, with a few converted Mohawks. They marched the 200 miles overland in about 22 days. Taking Fort Orange would have been a major blow against the English. At what is now Fort Edward, the French officers held council on the plan of attack. The leaders were Jacques le Moyne de Sainte-Hélène and Nicolas d'Ailleboust de Manthet. The second-in-command was the explorer and naval officer Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville.

The expedition made its way across the ice of Lake Champlain and Lake George toward the English settlements on the Hudson River. They found Fort Orange to be well defended, but a scouting party reported on February 8 that no one was guarding the stockade at the small frontier village of Schenectady to the west. Its residents were primarily Dutch Americans and held numerous Black slaves. Schenectady and Albany were so politically polarized in the wake of the 1689 Leisler's Rebellion that the opposing factions had not agreed on the setting of guards in the two settlements. The village of Schenectady (its name came from a Mohawk word meaning "beyond the Pines") was on a land patent to farm on the Great Flats of the Mohawk River originally granted by the Dutch in 1661. It was about seven miles beyond the western border of Rensselaerswyck.

Attack

Finding no sentinels other than two snowmen and the gate ajar, according to tradition, the raiders silently entered Schenectady two hours before dawn and launched their attack. They burned houses and barns and killed men, women, and children. Most of the victims were in night clothing and had no time to arm themselves. By the morning of February 9, the community lay in ruins, and more than 60 buildings were burned. Sixty residents were killed, including 11 Black slaves (referred to as "negroes' in the records). The French noted that about 50-60 residents survived and that 20 Mohawks had been spared so that the Natives would know their targets were the English, not the Mohawks. The 60 dead included 38 men, 10 women, and 12 children.

Among them were Dominie Petrus Tessemacher, the first Dutch Reformed Church pastor to be ordained in the Americas, and pastor of what became the First Reformed Church of Schenectady. The French had intended to take him captive to question him, but he was killed in his house. Reynier Schaets and a son were among the dead. Schaets was a son of Gideon Schaets, dominie of the Dutch Reformed Church at Albany. He was a surgeon, who had been appointed Justice at Schenectady by Leisler on December 28, 1689. His wife Catharina Bensing and three other children: Gideon, Bartholomew and Agnietje, survived. Of those who escaped from Schenectady to seek shelter, many died of exposure in the bitter cold before they reached safety.

The raiders departed with 27 prisoners, including five Black slaves, and 50 horses. John Alexander Glen, who lived in Scotia, across the river from Schenectady, had shown previous kindness to the French. In gratitude, the raiding party took the Schenectady prisoners to him and invited him to claim any relatives. Glen claimed as many survivors as he could, and the raiders took the rest to Montreal. Typically, the captives who were too young, old, or ill to keep up along such an arduous 200-mile journey were killed during the way. As was the pattern in later raids in New York and New England, many of the younger captives were adopted by Mohawk families in Canada. Some survivors had fled as refugees to the fort at Albany; Symon Schermerhorn was one of them.

Although wounded, he rode to Albany to warn them of the massacre. In commemoration, the mayor of Schenectady repeats the ride every year. Most mayors have done so on horseback, but a few have preferred the comfort of an automobile. A party of Albany militia and Mohawk warriors pursued the northern invaders and killed or captured 15 or more almost within sight of Montreal. Of the surviving captives, three males were redeemed: Johannes Teller and brothers Albert and Johannes Vedder. Jan Baptist Van Eps escaped from the Mohawk after three years and returned to Schenectady. Lawrence Vander Volgen lived with the Mohawk for 11 years and then returned and served as provincial interpreter.

Aftermath

The attack forced New York's political factions to put aside their differences and focus on the common enemy, New France. As a result of the attack, the Albany Convention, which had resisted Jacob Leisler's assumption of power in the southern parts of the colony, acknowledged his authority. With the assistance of Connecticut officials, Leisler organized a retaliatory expedition the next summer from Albany to attack Montreal. Led by Connecticut militia general Fitz-John Winthrop, the expedition turned back in August 1690 because of disease, lack of supplies, and insufficient watercraft for navigating on Lake Champlain.

In 1990, the city of Schenectady commissioned composer Maria Riccio Bryce to create a musical work to commemorate the tricentennial of the massacre. The resulting piece, Hearts of Fire, followed the lives of Schenectady townspeople through the seasons of 1689, set against the backdrop of the French march from Montreal to Albany. Though the settlers' losses were great in deaths and also captives taken, they elected to stay and rebuild, honoring the memory of their relatives.

See also

References

- Hyde, Anne F. (2022). Born of Lakes and Plains: Mixed-Descent Peoples and the Making of the American West. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 23. ISBN 9780393634099.

- ^ Jonathan Pearson, Chap. 9, "Burning of Schenectady", History of the Schenectady Patent in the Dutch and English Times, 1883, pp. 244-270

- ^ Hart, Larry. Tales of Old Schenectady, Chap. 8, pp. 37-40

- Bielinski, Stefan. "Schenectady", New York State Museum

- Wells, Robert V. (2000).Facing the "King of Terrors": Death and Society in an American Community, 1750-1990. Cambridge University Press, p. 28. ISBN 0521633192

- "An account of the burning of Schenectady by Mons. De Monsignat, comptroller General of the marine in Canada to Madam de Maintenon, the morganatic wife of Louis XIV.", Doc. Hist. N. Y., I, p. 186, noted in Pearson (1883), A History of the Schenectady Patent, Schenectady History Digital Archives

- John Demos, The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America, ISBN 978-0679759614

External links

- Journal of Robert Livingston, a settler Digital History, 2012, accessdate 6 January 2013.

- Detailed story, an online book

- Detailed story, Van Patten website

- "Why Schenectady was destroyed in 1690". A paper read before the Fortnightly Club of Schenectady, 3 May 1897, accessdate 6 January 2013.

- Symon Schermerhoorn's ride, February 8/9, 1690, writ from facts and traditions as set down in ye old records of ye massacre of Skinnechtady; and in commemoration of Symon Schermerhoorn's ride to save ye inhabitants of Albany from ye French and Indians, Privately printed, 1910, accessdate 6 January 2013.

42°49′08″N 73°56′53″W / 42.8188°N 73.9481°W / 42.8188; -73.9481

| New France | |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Colonies |

|

| Towns and villages |

|

| Forts | |

| Governments |

|

| Laws | |

| Economy | |

| Society | |

| Missionary groups | |

| Wars | |

- 1690 in the Thirteen Colonies

- King William's War

- Massacres by Native Americans

- Massacres in 1690

- Massacres in the Thirteen Colonies

- Military history of the Thirteen Colonies

- Pre-statehood history of New York (state)

- Schenectady, New York

- Massacres committed by the ancien régime

- Anti-Indigenous racism in New York (state)