| This article is missing information about Islamic, Indian, Mayan, Persian, and other scribes. Please expand the article to include this information. Further details may exist on the talk page. (July 2019) |

A scribe is a person who serves as a professional copyist, especially one who made copies of manuscripts before the invention of automatic printing.

The work of scribes can involve copying manuscripts and other texts as well as secretarial and administrative duties such as the taking of dictation and keeping of business, judicial, and historical records for kings, nobles, temples, and cities.

The profession of scribe first appears in Mesopotamia. Scribes contributed in fundamental ways to ancient and medieval cultures, including Egypt, China, India, Persia, the Roman Empire, and medieval Europe. Judaism, Buddhism, and Islam have important scribal traditions. Scribes have been essential in these cultures for the preservation of legal codes, religious texts, and artistic and didactic literature. In some cultures, social functions of the scribe and of the calligrapher overlap, but the emphasis in scribal writing is on exactitude, whereas calligraphy aims to express the aesthetic qualities of writing apart from its content.

Scribes, previously so widespread across cultures, lost most of their prominence and status with the advent of the printing press. The generally less prestigious profession of scrivener continued to be important for copying and writing out legal documents and the like. In societies with low literacy rates, street-corner letter-writers (and readers) may still be found providing scribe service.

Mesopotamia

See also: Sumerian literature and Cuneiform

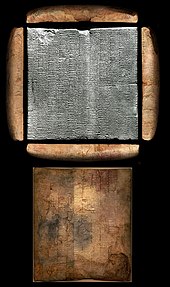

The Sumerians developed one of the earliest writing systems, the first body of written literature, and an extensive scribal profession to further these activities. The work of Near Eastern scribes primarily exists on clay tablets and stone monuments written in cuneiform, though later in the period of cuneiform writing they begin to use papyrus, parchment, and writing tablets. The body of knowledge that scribes possessed belonged to an elite urban culture, and few had access to it. Traveling scribes played a vital role in the dissemination of literary culture.

During the middle to late 3rd millennium BCE, Sumerian literature in the form of disputations proliferated, such as the Debate between bird and fish; the Debate between Summer and Winter, in which Winter wins; and others between the cattle and grain, the tree and the reed, silver and copper, the pickaxe and the plough, and the millstone and the gul-gul stone. Nearly all known Sumerian literary works were preserved as a result of young scribes apprenticing for their profession. In addition to literary works, the contents of the tablets they produced include word lists, syllabaries, grammar forms, and lists of personal names.

To the extent that the curriculum in scribal schools can be reconstructed, it appears that they would have begun by studying lists and syllabaries and learning metrology, the formulas for writing legal contracts, and proverbs. They then might have advanced to praise poems and finally to copying more sophisticated works of literature. Some scholars have thought that apprentice scribes listened to literary compositions read aloud and took dictation; others, that they copied directly from master copies. A combination of dictation, copying, and memorization for reproduction has also been proposed.

Ancient Egypt

See also: List of ancient Egyptian scribes and The Seated Scribe

One of the most important professionals in ancient Egypt was a person educated in the arts of writing (both hieroglyphics and hieratic scripts, as well as the demotic script from the second half of the first millennium BCE, which was mainly used as shorthand and for commerce) and arithmetic. Sons of scribes were brought up in the same scribal tradition, sent to school, and inherited their fathers' positions upon entering the civil service.

Much of what is known about ancient Egypt is due to the activities of its scribes and the officials. But because of their ability to study in the vast Egyptian libraries, they were entrusted with jobs bigger than just copyists. Monumental buildings were erected under their supervision, administrative and economic activities were documented by them, and stories from Egypt's lower classes and foreign lands survive due to scribes putting them in writing.

Scribes were considered part of the royal court, were not conscripted into the army, did not have to pay taxes, and were exempt from the heavy manual labor required of the lower classes (corvée labor). The scribal profession worked with painters and artisans who decorated reliefs and other building works with scenes, personages, or hieroglyphic text. However, the physical aspect of their work sometimes took a toll on their joints, with ancient bones showing some signs of arthritis that might be attributable to their profession.

| |

The demotic scribes used rush pens which had stems thinner than that of a reed (2 mm). The end of the rush was cut obliquely and then chewed so that the fibers became separated. The result was a short, stiff brush which was handled in the same manner as that of a calligrapher.

Thoth was the god credited with the invention of writing by the ancient Egyptians. He was the scribe of the gods who held knowledge of scientific and moral laws.

China

See also: Chinese calligraphy and Clerical script

The earliest known examples of writing in China are a body of inscriptions made on bronze vessels and oracle bones during the late Shang dynasty (c. 1250 – 1050 BCE), with the very oldest dated to c. 1200 BCE. It was originally used for divination, with characters etched onto turtle shells to interpret cracks caused by exposure to heat. By the sixth century BCE, scribes were producing books using bamboo and wooden slips. Each strip contained a single column of script, and the books were bound together with hemp, silk, or leather. China is well-known as being the place where paper was originally invented, likely by an imperial eunuch named Cai Lun in 105 CE. The invention of paper allowed for the later invention of woodblock printing, where paper was rubbed onto an inked slab to copy the characters. Despite this invention, calligraphy remained a prized skill due to the belief that "the best way to absorb the contents of a book was to copy it by hand".

Chinese scribes played an instrumental role in the imperial government's civil service. During the Tang dynasty, private collections of Confucian classics began to grow. Young men hoping to join the civil service would need to pass an exam based on Confucian doctrine, and these collections, which became known as "academy libraries" were places of study. Within this merit system, owning books was a sign of status. Despite the later importance of Confucian manuscripts, they were initially heavily resisted by the Qin dynasty. Though their accounts are likely exaggerated, later scholars describe a period of book burning and scholarly suppression. This exaggeration likely stems from Han dynasty historians being steeped in Confucianism as state orthodoxy.

Similarly to the west, religious texts, particularly Buddhist, were transcribed in monasteries and hidden during "times of persecution". In fact, the earliest known copy of a printed book is of the Diamond Sutra dating to 868 CE, which was found alongside other manuscripts within a walled-in cave called Dunhuang.

As professionals, scribes would undergo three years of training before becoming novices. The title of "scribe" was inherited from father to son. Early in their careers, they would work with local and regional governments and did not enjoy an official rank. A young scribe needed to hone their writing skills before specializing in an area like public administration or law. Archaeological evidence even points to scribes being buried with marks of their trade such as brushes, "administrative, legal, divinatory, mathematical, and medicinal texts", thus displaying a personal embodiment of their profession.

South Asia

The Buddhist Tripiṭaka emerged at the beginning of the first century. Buddhist texts were treasured and sacred throughout Asia and were written in different languages. Buddhist scribes believed that, “The act of copying them could bring a scribe closer to perfection and earn him merit.”

Rather later, Hindu texts were written, although the most sacred, especially the Vedas, were not written down until much later, and were learnt by heart by the priestly Brahmins. Writing in the several scripts of Indic languages was generally not regarded as a distinct artistic form, in a situation similar to Europe, but different from East Asian traditions of calligraphy.

Japan

See also: Japanese calligraphy and Writing in the Ryukyu KingdomBy the 5th century CE, written Chinese was being adapted in Japan to represent spoken Japanese. The complexity of reconciling Japanese with a system of writing not meant to express it meant that acquiring literacy was a long process. Phonetic syllabaries (kana), used for private writing, were developed by the 8th century and were in use along with kanji, the logographic system, used for official records. Gendering of the private and public spheres led to a characterization of kana as more feminine and kanji as masculine, but women of the court were educated and knew kanji, and men also wrote in kana, while works of literature were produced in both.

The earliest extant writings take the form of mokkan, wooden slips used for official memoranda and short communications and for practical purposes such as shipping tags; inscriptions on metal and stone; and manuscripts of sutras and commentaries. Mokkan were often used for writing practice. Manuscripts first took the form of rolls made from cloth or sheets of paper, but when manuscripts began to appear as bound books, they coexisted with handscrolls (makimono).

The influence of Chinese culture, especially written culture, made writing "immensely important" in the early Japanese court. The earliest Japanese writing to survive dates from the late Asuka and Nara periods (550–794), when Buddhist texts were being copied and disseminated. Because Buddhism was text-based, monks were employed in scribal and bureaucratic work for their skill in writing and knowledge of Chinese culture. In portraits of Buddhist clerics, a handscroll is a symbol of scribal authority and the possession of knowledge.

Government offices and Buddhist centers employed copyists on a wide scale, requiring an abundance of materials such as paper, glue, ink, and brushes; exemplars from which to copy; an organizational structure; and technicians for assembly, called sōkō or sō’ō. More than 10,000 Nara documents are preserved in the Shōsōin archives of the Tōdai-ji temple complex. The institution of the ritsuryō legal state from the 8th to 10th centuries produced "a mountain of paperwork" employing hundreds of bureaucratic scribes in the capital and in the provinces. The average sutra copyist is estimated to have generated 3,800–4,000 characters a day. Scribes were paid by the "page," and the fastest completed thirteen or more sheets a day, working on a low table and seated on the floor. Both speed and accuracy mattered. Proofreaders checked the copy against the exemplar, and the scribe's pay was docked for errors.

In the 8th century, the demand for vast quantities of copies meant that scribes in the Office of Sutra Transcription were lay people of common status, not yet ordained monks, some finding opportunities for advancement. In Classical Japan, even lay scribes at some sutra copyist centers were required to practice ritual purity through vegetarian dietary restrictions, wearing ritual garments (jōe), ablution, avoiding contact with death and illness, and possibly sexual abstinence. Outside Buddhist centers, professional scriveners practiced copyist craft. Court-commissioned chronicles of the 8th century, such as Kojiki and Nihon shoki, survive in much later copies, as is the case for the first Japanese poetry anthologies.

The earliest printed books were produced under the Empress Shōtoku on a large scale in the 8th century, only three centuries after Japanese became a written language, and by the Edo period (1603–1868) bound printed books predominated. Manuscripts remained valued for their aesthetic qualities, and the scribal tradition continued to flourish for a wide range of reasons. In addition to handwritten practical documents pertaining to legal and commercial transactions, individuals might write journals or commonplace books, which involved copying out sometimes lengthy passages by hand. This copying might extend to complete manuscripts of books that were expensive or not readily available to buy.

But scribal culture was not merely or always a matter of need or necessity. Copying Buddhist sutras was a devotional practice (shakyō). In the Nara period, wealthy patrons commissioned sutra copying on behalf of ancestors to gain them spiritual passage from the Buddhist hells. The Edo-period court noble Konoe Iehiro created a sutra manuscript in gold ink on dark blue paper, stating his purpose in the colophon as "to ensure the spiritual enlightenment of his departed mother."

Creating a calligraphic and pictorial work by copying secular literature likewise was an aesthetic practice for its own sake and a means of study. Within the social elite of the court, calligraphy was thought to express the inner character of the writer. In the Heian period, the book collector, scholar-scribe, and literary artist Fujiwara no Teika was a leader in preserving and producing quality manuscripts of works of literature. Even so prolific an author of printed prose works as Ihara Saikaku (1642–1693) also produced handwritten works in several formats, including manuscripts, handscrolls, and poetry slips (tanzaku) and cards (shikishi). Unique and prized handscrolls preserved the collaborative poetry sessions characteristic of renga and haikai poetic composition, distributed more widely in printed copies.

For authors not located near the major centers of publishing and printing, manuscripts were a route to publication. Some authors self-published their books, especially romance novels (ninjōbon), in manuscript form. Women's prose writings in general were circulated as manuscripts during the Edo period. Women were not prevented from writing and circulating their work, but private publication may have been a way for women to adhere to gender norms in not making themselves available in the public sphere.

Manuscripts could more readily evade government censorship, and officially banned books that could no longer be printed were copied for personal use or circulated privately. Lending libraries (kashihon'ya) offered manuscript books, including illicit texts, along with printed books. Books might also be composed as manuscripts when their transmission was limited to a particular circle of interested parties or sharers in the knowledge, such as local history and antiquarianism, a family's accumulated lore or farming methods, or medical texts of a particular school of medicine. Intentional secrecy might be desired to protect arcane knowledge or proprietary information with commercial value.

In the esoteric strand of Japanese Buddhism, scribes recorded oracles, the utterances of a kami-inspired person often in the form of dialogues in response to questions. The transcriber also filled in context for the transmission. After the text was verified, it became part of the canon, stored in secret places, viewable by affiliated monks, and used to legitimate forms of religious authority. Because they dealt with genealogies and sacral boundaries, oracle texts were consulted as references in questions of lineage and land ownership.

At contemporary Shinto or Buddhist shrines, scribal traditions still play a role in creating ofuda (talismans), omikuji (fortunes or divination lots), ema (votive tablets), goshuin (calligraphic visitor stamps), and gomagi (inscribed sticks for ritual burning), forms that may employ a combination of stamps and handwriting on media. Today these are often mass produced and commercialized for marketing to tourists. Ema, for instance, began as large-scale pictorial representations that historically were created by professional artists. Small versions began to be produced and sold, and a complex symbology developed for the messages. Modern versions sold at shrines, often already stamped with their local affiliation, tend to be used more verbally, with space left for individuals to act as their own scribes in messaging the kami.

Judaism

Scribes of ancient Israel were a literate minority in an oral based-culture. Some of them belonged to the priestly class, other scribes were the record-keepers and letter-writers in the royal palaces and administrative centers, affiliated with the ancient equivalent of professional guilds. There were no scribal schools in Israel during the early part of the Iron Age (1200–800 B.C.E.). Between the 13th and 8th centuries B.C.E., the Hebrew alphabetic system had not been developed. Only after the appearance of the Kingdom of Israel, Finkelstein points to the reign of Omri, did the scribal schools begin to develop, reaching their culmination in the time of Jeroboam II, under Mesopotamian influence. The eventual standardization of the Hebrew writing system between the eighth and sixth centuries B.C.E. would presumably have given rise to codified rules and principles of language that scribes would then have learned. The education of scribes in ancient Israel was supported by the state, although some scribal arts could have been taught within a small number of families. Some scribes also copied documents, but this was not necessarily part of their job.

The Jewish scribes used the following rules and procedures while creating copies of the Torah and eventually other books in the Hebrew Bible.

- They could only use clean animal skins, both to write on, and even to bind manuscripts.

- Each column of writing could have no less than 48, and no more than 60, lines.

- The ink must be black, and of a special recipe.

- They must say each word aloud while they were writing.

- They must wipe the pen and wash their entire bodies before writing the most Holy Name of God, YHVH, every time they wrote it. Also before they would write the Most Holy Name of God, they would wash their hands 7 times.

- There must be a review within thirty days, and if as many as three pages required corrections, the entire manuscript had to be redone.

- The letters, words, and paragraphs had to be counted, and the document became invalid if two letters touched each other. The middle paragraph, word and letter must correspond to those of the original document.

- The documents could be stored only in sacred places (synagogues, etc.).

- As no document containing God's Word could be destroyed, they were stored, or buried, in a genizah (Hebrew: "storage").

Sofer

Main article: SoferSofers (Jewish scribes) are among the few scribes that still do their trade by hand, writing on parchment. Renowned calligraphers, they produce the Hebrew Torah scrolls and other holy texts.

Accuracy

Further information: Dead Sea ScrollsUntil 1948, the oldest known manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible dated back to CE 895. In 1947, a shepherd boy discovered some scrolls dated between 100 BCE and CE 100, inside a cave west of the Dead Sea. Over the next decade, more scrolls were found in caves and the discoveries became known collectively as the Dead Sea Scrolls. Every book in the Hebrew Bible was represented except Esther. Numerous copies of each book were discovered, including 25 copies of the book of Deuteronomy.

While there were other items found among the Dead Sea Scrolls not currently in the Hebrew Bible, and many variations and errors occurred when they were copied, the texts, on the whole, testify to the accuracy of the scribes. The Dead Sea Scrolls are currently the best route of comparison to the accuracy and consistency of translation for the Hebrew Bible because they are the oldest out of any biblical text currently known.

Corrections and editing

Priests who took over the leadership of the Jewish community preserved and edited biblical literature. Biblical literature became a tool that legitimated and furthered the priests' political and religious authority.

Corrections by the scribes (Tiqqun soferim) refers to changes that were made in the original wording of the Hebrew Bible during the second temple period, perhaps sometime between 450 and 350 BCE. One of the most prominent men at this time was Ezra the scribe. He also hired scribes to work for him, in order to write down and revise the oral tradition. After Ezra and the scribes had completed the writing, Ezra gathered the Jews who had returned from exile, all of whom belonged to Kohanim families. Ezra read them an unfamiliar version of the Torah. This version was different from the Torah of their fathers. Ezra did not write a new bible. Through the genius of his ‘editing', he presented the religion in a new light.

Ancient Rome

See also: Scriba (ancient Rome) and Roman Empire § Literacy, books, and education

Ancient Rome had several occupations for which the ability to write accurately and clearly was the primary qualification. The English word “scribe” derives from the Latin word scriba, a public notary or clerk. The public scribae were the highest in rank of the four prestigious occupational grades (decuriae) among the attendants of the Roman magistrates.

In the city of Rome, the scribae worked out of the state treasury and government archive. They received a good salary. Scribae were often former slaves and their sons; other literary or educated men who advanced to the job through patronage; or even men as highly ranked as the equestrian order. Among the writing duties of a scriba was the recording of sworn oaths on public tablets. The office afforded several advantages, including a knowledge of Roman law that was traditionally the privilege of the elite. People who needed legal documents drawn up and whose own literacy was low could make use of a public scribe. A scriba might also be a private secretary.

A tabellio (Greek agoraios) was a lower rank of scribe or notary who worked in civil service. A notarius was a stenographer.

An amanuensis was a scribe who took dictation and perhaps offered some compositional polish. Amanuenses were typically Greek and might be either male or female. Upper-class Romans made extensive use of dictation, and Julius Caesar was said to employ as many as four secretaries at once on different projects. The Apostle Paul, a Roman citizen literate in Greek, made use of an amanuensis for his epistles. It was considered impolite, however, to use a scribe for writing personal letters to friends; these were to be written by one's own hand. The Vindolanda tablets (early 2nd century CE) from a fort in Roman Britain contain several hundred examples of handwriting; a few tablets stand out as having been written by professional scribes.

Some Roman households had libraries extensive enough to require specialized staff including librarii, copyists or scribes, who were often slaves or freedmen, along with more general librarians (librarioli). Public libraries also existed under imperial sponsorship, and bookshops both sold books and employed independent librarii along with other specialists who constructed the scrolls. A copyist (librarius or libraria) was said to need an "irrational knack" for copying text accurately without slowing down to comprehend it. Some literary slaves specialized in proofreading.

Occasionally even senators took dictation or copied texts by hand for personal use, as did grammatici (“grammarians” or professors of higher education), but generally the routine copying of manuscripts was a task for educated slaves or for freedpersons who worked independently in bookshops. Books were a favored gift for friends, and since they had to be individually written out, "deluxe" editions, made from higher-grade papyrus and other fine materials, might be commissioned from intellectuals who also acted as editors. Unscrupulous copyists might produce and trade in unauthorized editions, sometimes passing them off as autograph manuscripts by famous authors.

The literacy of a librarius was also valued in business settings, where they might serve as clerks. For example, a libraria cellaria would be a woman who kept business records such as inventories. An early 2nd-century marble relief from Rome depicts a female scribe, seated on a chair and writing on kind of a tablet, facing the butcher who is chopping meat at a table.

Eleven Latin inscriptions uncovered from Rome identify women as scribes in the sense of copyists or amanuenses (not public scribae). Among these are Magia, Pyrrhe, Vergilia Euphrosyne, and a freedwoman whose name does not survive; Hapate, a shorthand writer of Greek who lived to the age of 25; and Corinna, a storeroom clerk and scribe. Three are identified as literary assistants: Tyche, Herma, and Plaetoriae.

Europe in the Middle Ages

See also: Illuminated manuscriptsMonastic scribes

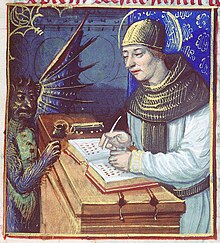

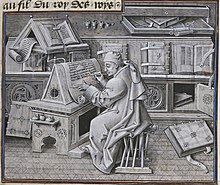

In the Middle Ages, every book was made by hand. Specially trained monks, or scribes, had to carefully cut sheets of parchment, make the ink, write the script, bind the pages, and create a cover to protect the script. This was all accomplished in a monastic writing room called a scriptorium which was kept very quiet so scribes could maintain concentration. A large scriptorium may have up to 40 scribes working.

Scribes woke to morning bells before dawn and worked until the evening bells, with a lunch break in between. They worked every day except for the Sabbath. The primary purpose of these scribes was to promote the ideas of the Christian Church, so they mostly copied classical and religious works. The scribes were required to copy works in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew whether or not they understood the language. These re-creations were often written in calligraphy and featured rich illustrations, making the process incredibly time-consuming. Scribes had to be familiar with the writing technology as well. They had to make sure that the lines were straight and the letters were the same size in each book that they copied. It typically took a scribe fifteen months to copy a Bible.

Such books were written on parchment or vellum made from treated hides of sheep, goats, or calves. These hides were often from the monastery's own animals as monasteries were self-sufficient in raising animals, growing crops, and brewing beer. The overall process was too extensive and costly for books to become widespread during this period.

Although scribes were only able to work in daylight, due to the expense of candles and the rather poor lighting they provided, monastic scribes were still able to produce three to four pages of work per day. The average scribe could copy two books per year. They were expected to make at least one mistake per page.

During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, copying became more of a specialized activity and was increasingly performed by specialists. To meet expanding demand, the pecia system was introduced, in which different parts of the same text were assigned to hired copiers working both in and out of the monasteries.

Female scribes

Women also played a role as scribes in Anglo-Saxon England, as religious women in convents and schools were literate. Excavations at medieval convents have uncovered styli, indicating that writing and copying were done at those locations. Also, female pronouns are used in prayers in manuscripts from the late 8th century, suggesting that the manuscripts were originally written by and for female scribes.

In the 12th century within a Benedictine monastery at Wessobrunn, Bavaria there lived a female scribe named Diemut. She lived within the monastery as recluse and professional scribe. Two medieval book lists exist that have named Diemut as having written more than forty books. Fourteen of Diemut's books are in existence today. Included in these are four volumes of a six volume set of Pope Gregory the Great's Moralia in Job, two volumes of a three-volume Bible, and an illuminated copy of the Gospels. It has been discovered that Diemut was a scribe for as long as five decades. She collaborated with other scribes in the production of other books. Since the Wessobrunn monastery enforced its strict claustration it is presumed that these other scribes were also women. Diemut was credited with writing so many volumes that she single-handedly stocked the Wessobrunn's library. Her dedication to book production for the benefit of the Wessobrunn monks and nuns eventually led to her being recognized as a local saint. At the Benedictine monastery within Admont, Austria it was discovered that some of the nuns had written verse and prose in both Latin and German. They delivered their own sermons, took dictation on wax tablets, and copied and illuminated manuscripts. They also taught Latin grammar and biblical interpretation at the school. By the end of the 12th century they owned so many books that they needed someone to oversee their scriptorium and library. Two female scribes have been identified within the Admont Monastery; Sisters Irmingart and Regilind.

There are several hundred women scribes that have been identified in Germany. These women worked within German women's convent from the thirteenth to the early 16th century. Most of these women can only be identified by their names or initials, by their label as "scriptrix", "soror", "scrittorix", "scriba" or by the colophon (scribal identification which appears at the end of a manuscript). Some of the women scribes can be found through convent documents such as obituaries, payment records, book inventories, and narrative biographies of the individual nuns found in convent chronicles and sister books. These women are united by their contributions to the libraries of women's convents. Many of them remain unknown and unacknowledged but they served the intellectual endeavor of preserving, transmitting and on occasion creating texts. The books they left their legacies within were usually given to the sister of the convent and were dedicated to the abbess, or given or sold to the surrounding community. There are two obituaries that have been found that date back to the 16th century, both of the obituaries describe the women who died as a "scriba". In an obituary found from a monastery in Rulle, describes Christina Von Haltren as having written many other books.

Women's monasteries were different from men's in the period from the 13th to the 16th century. They would shift their order depending on their abbess. If a new abbess would be appointed then the order would change their identity. Every time a monastery would shift their order they would need to replace, correct and sometimes rewrite their texts. Many books survived from this period. Approximately 4,000 manuscripts have been discovered from women's convents from late medieval Germany. Women scribes served as the business women of the convent. They produced a large amount of archival and business materials, they recorded the information of the convent in the form of chronicles and obituaries. They were responsible for producing the rules, statutes and constitution of the order. They also copied a large amount of prayer books and other devotional manuscripts. Many of these scribes were discovered by their colophon.

Despite women being barred from transcribing Torah scrolls for ritual use, a few Jewish women between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries are known to have copied other Hebrew manuscripts. They learned the craft from male scribes they were related to, and were unusual because women were not typically taught Hebrew. Knowledge of these women scribes comes from their colophon signatures.

Town scribe

The scribe was a common job in medieval European towns during the 10th and 11th centuries. Many were employed at scriptoria owned by local schoolmasters or lords. These scribes worked under deadlines to complete commissioned works such as historic chronicles or poetry. Due to parchment being costly, scribes often created a draft of their work first on a wax or chalk tablet.

Notable scribes

- Ahmes, 15th Dynasty Egyptian scribe

- Amat-Mamu, Naditu priestess and Babylonian temple scribe

- Amina, bint al-Hajj ʿAbd al-Latif, a Moroccan jurist and scribe

- Baruch ben Neriah, the scribe and friend of the biblical prophet Jeremiah

- Ben Sira, Hellenistic Jewish scribe of the Second Temple period

- Dubhaltach MacFhirbhisigh, 17th-century Irish scribe and Gaelic scholar

- Ezra, Jewish sofer in the early Second Temple period

- Máel Muire mac Céilechair, a principal scribe of the Lebor na hUidre manuscript

- Metatron, celestial scribe in the angelology tradition

- Poggio Bracciolini, Italian Renaissance scholar known for his humanist script

- Sidney Rigdon, scribe who assisted with the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible

- Sîn-lēqi-unninni, a Mesopotamian priest and scholar thought to have compiled the best-preserved version of Gilgamesh

- Zayd ibn Thabit, the personal scribe of Muhammad

Gallery

-

Assyrian scribe documenting a battle scene (9th–7th century BCE)

Assyrian scribe documenting a battle scene (9th–7th century BCE)

-

Mayan scribes (550–950 CE)

Mayan scribes (550–950 CE)

-

Gregory the Great and scribes (10th century)

Gregory the Great and scribes (10th century)

-

German monastic scribe astride a wyvern (mid-12th century)

German monastic scribe astride a wyvern (mid-12th century)

-

Luis de Santángel (d. 1498), escribano de ració (scrivener of accounting) to Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain

Luis de Santángel (d. 1498), escribano de ració (scrivener of accounting) to Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain

-

Colophon portrait of Daulat and the scribe 'Abd al-Rahim ("Amber-pen"), from the Khamsa of Nizami (1595–96)

Colophon portrait of Daulat and the scribe 'Abd al-Rahim ("Amber-pen"), from the Khamsa of Nizami (1595–96)

See also

- Asemic writing

- Scrivener

- Worshipful Company of Scriveners

- Katib and Naskh

- Islamic manuscripts and Islamic calligraphy

- Arabic calligraphy

- Persian calligraphy

- List of obsolete occupations

References

- Harper, Douglas (2010). "Scribe". Dictionary.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Dictionary.com, LLC. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Scribes". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Scribes". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

- Cory MacPherson, Inventions in Reading and Writing: From Calligraphy to E-readers (Cavendish Square, 2017), pp. 22–23.

- "Women of letters doing write for the illiterate". smh.com.au. Reuters. 12 June 2003. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Roger Matthews, "Writing (and Reading) as Material Practice: The World of Cuneiform Culture as an Arena for Investigation," in Writing as Material Practice: Substance, Surface and Medium (Ubiquity, 2013), p. 72.

- Massimo Maoicchi, "Writing in Early Mesopotamia: The Historical Interplay of Technology, Cognition, and Environment," in Beyond the Meme: Development and Structure in Cultural Evolution (University of Minnesota Press, 2019), p. 408.

- Daniel Arnaud, "Scribes and Literature," Near Eastern Archaeology 63:4, The Mysteries of Ugarit: History, Daily Life, Cult (2000), p. 199

- "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". Etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk. 2006-12-19. Retrieved 2017-03-09.

- "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". Etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk. 2006-12-19. Retrieved 2017-03-09.

- Paul Delnero, "Memorization and the Transmission of Sumerian Literary Compositions," Journal of Near Eastern Studies 71:2 (October 2012), p. 189.

- Delnero, "Memorization and Transmission," p. 189.

- Delnero, "Memorization and Transmission," p. 190.

- As reviewed by Delnero, "Memorization and Transmission," p. 191.

- Rice, Michael (1999). Who's Who in Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge. p. lvi. ISBN 978-0415154482.

- Damerow, Peter (1996). Abstraction and Representation: Essays on the Cultural Evolution of Thinking. Dordrecht: Kluwer. pp. 188–. ISBN 978-0792338161.

- Carr, David M. (2005). Writing on the Tablet of the Heart: Origins of Scripture and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0195172973.

- ^ Kemp, Barry J. (2006). Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. p. 180. ISBN 978-0415235495.

- Lidz, Franz (2024-08-16). "Ancient Scribes Got Ergonomic Injuries, Too". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-08-26.

- Clarysse, Willy (1993). "Egyptian Scribes Writing Greek". Chronique d'Égypte. 68 (135–136): 186–201. doi:10.1484/J.CDE.2.308932.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (1969). The Gods of the Egyptians. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486220550.

- Kern, Martin (2010). Owen, Stephen (ed.). The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, vol. 1: To 1375. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-85558-7.

- Keightley, David (1978). Sources of Shang history: the oracle-bone inscriptions of bronze-age China. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. xvi. ISBN 978-0-520-02969-9.

- Bagley, Robert (2004). "Anyang writing and the origin of the Chinese writing system". In Houston, Stephen (ed.). The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge University Press. pp. 190–249. ISBN 978-0-521-83861-0.

- Boltz, William G. (1999). "Language and Writing". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge University Press. pp. 74–123. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521470308.004. ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books A Living History. United Kingdom: Thames & Hudson. pp. 18–20. ISBN 978-0-500-29115-3.

- Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library An Illustrated History. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. pp. 47–49. ISBN 978-1-60239-706-4.

- Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library An Illustrated History. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-60239-706-4.

- Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books A Living History. United Kingdom: Thames & Hudson. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-500-29115-3.

- Selbitschka, Armin (2018). "I Write Therefore I Am: Scribes, Literacy, and Identity in Early China". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 78 (2): 413–476. doi:10.1353/jas.2018.0029. S2CID 195510449. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- Lyons, Martyn (2013). Books: a living history. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-500-29115-3. OCLC 857089276.

- Andrew T. Kamei-Dyche, "The History of Books and Print Culture in Japan: The State of the Discipline," Book History 14 (2011), p. 270.

- Kamei-Dyche, "The History of Books and Print Culture," pp. 270–271.

- ^ Kamei-Dyche, "The History of Books and Print Culture," p. 271.

- Joan R. Piggott, "Mokkan: Wooden Documents from the Nara Period," Monumenta Nipponica 45:4 (1990), pp. 449–450.

- Kamei-Dyche, "The History of Books and Print Culture," p. 293, n. 8.

- ^ Kamei-Dyche, "The History of Books and Print Culture," p. 272.

- Kamei-Dyche, "The History of Books and Print Culture," p. 294, n. 15.

- Radu Leca, "Dynamic Scribal Culture in Late Seventeenth-Century Japan: Ihara Saikaku's Engagement with Handscrolls," Japan Review 37 (2022), p. 82.

- Bryan Lowe, "Texts and Textures of Early Japanese Buddhism: Female Patrons, Lay Scribes, and Buddhist Scripture in Eighth-Century Japan," Princeton University Library Chronicle 73:1 (2011), pp. 23–26.

- Piggott, "Mokkan," p. 449.

- Alexander N. Mesheryakov, "On the Quantity of Written Data Produced by the Ritsuryō State," Japan Review 15 (2003), pp. 187, 193.

- Mesheryakov, "On the Quantity of Written Data," p. 187.

- Lowe, "Texts and Textures," pp. 28–29.

- Lowe, "Texts and Textures," p. 29.

- Bryan D. Lowe, "The Discipline of Writing: Scribes and Purity in Eighth-Century Japan," Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 39:2 (2012), p. 210, 229.

- Lowe, "The Discipline of Writing," pp. 201-221, 228–229.

- Lowe, "The Discipline of Writing," p. 227.

- ^ Kamei-Dyche, "The History of Books and Print Culture," p. 273.

- P. F. Kornicki, "Manuscript, Not Print: Scribal Culture in the Edo Period," Journal of Japanese Studies 32:1 (2006), pp. 23-52.

- Kornicki, "Manuscript, Not Print," p. 28.

- Kornicki, "Manuscript, Not Print," pp. 28–30.

- Lowe, "Texts and Textures," pp. 18–20.

- ^ Kornicki, "Manuscript, Not Print," p. 29.

- Kamei-Dyche, "The History of Books and Print Culture," pp. 293–294, n. 13.

- Leca, "Dynamic Scribal Culture," pp. 78, 89.

- Leca, "Dynamic Scribal Culture," pp. 86–88.

- Peter Kornicki, "Keeping Knowledge Secret in Edo-Period Japan (1600–1868)," Textual Cultures 14:1 (2021), p. 3-18.

- Kornicki, "Manuscript, Not Print," pp. 25–26.

- Kornicki, "Manuscript, Not Print," p. 34.

- Kornicki, "Keeping Knowledge Secret," p. 18.

- Kornicki, "Manuscript, Not Print," pp. 31–32, 37–40.

- Kornicki, "Manuscript, Not Print," p. 25.

- Local archives of handscrolls are referenced in village boundary disputes in Ihara Saikaku's story collection Honchō ōin hiji (Trials under the Shade of Cherry Trees in Our Land, 1689); Leca, "Dynamic Scribal Culture," pp. 82–83.

- Kornicki, "Manuscript, Not Print," pp. 33–35.

- Kornicki, "Keeping Knowledge Secret," pp. 3-19.

- Elizabeth Tinsley, "Indirect Transmission in Shingon Buddhism: Notes on the Henmyōin Oracle," The Eastern Buddhist 45:1/2 (2014), pp. 77-112, especially 77–78, 82, 84, 87–88, 92ff. (on lineage and land).

- Caleb Carter, "Power Spots and the Charged Landscape of Shinto," Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 45:1 (2018), pp. 160 (on commercialization), 162 (ofuda and omikuji), and 167 (goshuin).

- Yamanaka Hiroshi, 山中 弘, "Religious Change in Modern Japanese Society: Established Religions and Spirituality," Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 48:2 (2021), pp. 365-382, especially pp. 368, 372 (on goshuin), 374 (on gomagi and the importation of Western vocabulary such as "spiritual supplements").

- Ian Reader, "Letters to the Gods: The Form and Meaning of Ema," Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 18:1 (1991), pp. 30–37.

- Schniedewind, William M.(2014) UNDERSTANDING SCRIBAL EDUCATION IN ANCIENT ISRAEL:A VIEW FROM KUNTILLET ʿAJRUD.In: MAARAV 21.1–2 pp.272 ff.

- Werrett, Ian. How Did Scribes and the Scribal Tradition Shape the Hebrew Bible?

- Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D. (1993). The Oxford Companion to the Bible (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195046458.

- Manning, Scott (17 March 2007). "Process of copying the Old Testament by Jewish Scribes". Historian on the Warpath. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Johnson, Paul (1993). A History of the Jews (2nd ed.). London: Phoenix. p. 91. ISBN 978-1857990966.

-

Johnson, Paul (8 August 2013) . A History of the Jews. Hachette UK (published 2013). ISBN 9781780226699. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

The Dead Sea Scrolls testify, on the whole, to the accuracy with which the Bible was copied through the ages .

- Johnson, Paul (1993). A History of the Jews (2nd ed.). London: Phoenix. p. 91. ISBN 978-1857990966.

- Schniedewind, William M. (18 November 2008). "Origins of the Written Bible". Nova. PBS Online. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Drazin, Israel (26 August 2015). "Ezra changed the Torah text". Jewish Books. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Okouneff, M. (23 January 2016). Greenburg, John (ed.). The Wrong Scribe: The Scribe Who Revised the King David Story. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 146. ISBN 9781523640430.

- Gilad, Elon (22 October 2014). "Who Wrote the Torah?". Haaretz. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Marietta Horster, "Living on Religion: Professionals and Personnel," in A Companion to Roman Religion (Blackwell, 2007), p. 334; Daniel Peretz, "The Roman Interpreter and His Diplomatic and Military Roles," Historia 55 (2006), p. 452.

- David Armstrong, Horace (Yale University Press, 1989), p. 18.

- Clifford Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire (University of California Press, 2000), p. 96.

- T.R.S. Broughton, The Magistrates of the Roman Republic (American Philological Association, 1951, 1986), vol. 1, pp. 166–168.

- T. J. Kraus, "(Il)literacy in Non-Literary Papyri from Graeco-Roman Egypt: Further Aspects of the Educational Ideal in Ancient Literary Sources and Modern Times," Mnemosyne 53:3 (2002), pp. 325–327; Clifford Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire (University of California Press, 2000), p. 101.

- Peter White, "Bookshops in the Literary Culture of Rome," in Ancient Literacies: The Culture of Reading in Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 269, note 4.

- Marcus Niebuhr Tod, “A New Fragment of the Edictum Diocletiani,” Journal of Hellenic Studies 24 (1904), pp. 195-202.

- Nicholas Horsfall, “Rome without Spectacles,” Greece & Rome 42:1 (1995), p. 50.

- Myles McDonnell, "Writing, Copying, and Autograph Manuscripts in Ancient Rome," Classical Quarterly 46:2 (1996), p. 473.

- Clarence A. Forbes, "The Education and Training of Slaves in Antiquity," Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 86 (1955), p. 341.

- Susan Treggiari, "Jobs for Women," American Journal of Ancient History 1 (1976), p. 78.

- Nicholas Horsfall, “Rome without Spectacles,” p. 51, citing Pliny the Elder, Natural History 7.19; Cicero, Brutus 87.

- Chris Keith, "'In My Own Hand': Grapho-Literacy and the Apostle Paul," Biblica 89:1 (2008), pp. 39-58.

- McDonnell, "Writing, Copying, and Autograph Manuscripts," p. 474.

- McDonnell, "Writing, Copying, and Autograph Manuscripts," p. 471.

- George W. Houston, “The Slave and Freedman Personnel of Public Libraries in Ancient Rome,” Transactions of the American Philological Association 132:1/2 (2003), p. 147.

- McDonnell, "Writing, Copying, and Autograph Manuscripts," p. 473.

- McDonnell, "Writing, Copying, and Autograph Manuscripts," p. 477.

- McDonnell, "Writing, Copying, and Autograph Manuscripts," p. 477 "et passim’’.

- McDonnell, "Writing, Copying, and Autograph Manuscripts," p. 479.

- McDonnell, "Writing, Copying, and Autograph Manuscripts," p. 478

- Andrew Garland, “Cicero's Familia Urbana,” Greece & Rome 39:2 (1992), p. 167.

- Garland, “Cicero's Familia Urbana,” p. 164.

- Haines-Eitzen, Kim (Winter 1998). "Girls Trained in Beautiful Writing: Female Scribes in Roman Antiquity and Early Christianity". Journal of Early Christian Studies. 6 (4): 629–646. doi:10.1353/earl.1998.0071. S2CID 171026920.

- "Werken". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 2020-08-21.

- ^ Pavlik, John; McIntosh, Shawn (2017). Converging Media: A New Introduction to Mass Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9780190271510.

- ^ Murray, Stuart A.P. (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing. pp. 33–34. ISBN 9781602397064.

- ^ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living History. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. pp. 36–38, 41. ISBN 9781606060834.

- ^ Martyn., Lyons (2011). Books : a living history. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 9781606060834. OCLC 707023033.

- Lyons, M. (2011). Books: A Living History. Getty Publications.

- Lady Science (16 February 2018). "Women Scribes: The Technologists of the Middle Ages". The New Inquiry.

- "Female Scribes in Early Manuscripts". Medieval manuscripts blog.

- Hall, Thomas N. (Summer 2006). "Women as Scribes: Book Production and Monastic Reform in Twelfth Century Bavaria". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 37: 160–162. doi:10.1086/SCJ20477735 – via Gale.

- ^ Cyrus, Cynthia (2009). The Scribe for Women's Convents in Late Medieval Germany. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802093691.

- Riegler, Michael; Baskin, Judith R. (2008). ""May the Writer Be Strong": Medieval Hebrew Manuscripts Copied by and for Women". Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues (16): 9–28. doi:10.2979/nas.2008.-.16.9. ISSN 0793-8934. JSTOR 10.2979/nas.2008.-.16.9. S2CID 161946788.

- Murray, Stuart A.P. (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 9781602397064.

Further reading

- Avrin, Leila (2010). Scribes, Scripts and Books. ALA Publishing. ISBN 978-0838910382.

- Martin, Henri-Jean (1995). The History and Power of Writing. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-50836-6.

- Tahkokallio, Jaako. (2019). “Counting Scribes: Quantifying the Secularization of Medieval Book Production”. Book History, 22(1), pg. 1-42.

- Richardson, Ernest Gushing (1911). Some Old Egyptian Librarians. Charles Sribners.

External links

- Catholic Encyclopedia. newadvent.org.