| This article needs attention from an expert in geometry. The specific problem is: Other users have requested expert review on talk page. WikiProject Geometry may be able to help recruit an expert. (August 2023) |

Mathematical construct in engineering This article is about the geometrical property of an area, termed the second moment of area. For the moment of inertia dealing with the rotation of an object with mass, see Moment of inertia. For a list of equations for second moments of area of standard shapes, see List of second moments of area.

The second moment of area, or second area moment, or quadratic moment of area and also known as the area moment of inertia, is a geometrical property of an area which reflects how its points are distributed with regard to an arbitrary axis. The second moment of area is typically denoted with either an (for an axis that lies in the plane of the area) or with a (for an axis perpendicular to the plane). In both cases, it is calculated with a multiple integral over the object in question. Its dimension is L (length) to the fourth power. Its unit of dimension, when working with the International System of Units, is meters to the fourth power, m, or inches to the fourth power, in, when working in the Imperial System of Units or the US customary system.

In structural engineering, the second moment of area of a beam is an important property used in the calculation of the beam's deflection and the calculation of stress caused by a moment applied to the beam. In order to maximize the second moment of area, a large fraction of the cross-sectional area of an I-beam is located at the maximum possible distance from the centroid of the I-beam's cross-section. The planar second moment of area provides insight into a beam's resistance to bending due to an applied moment, force, or distributed load perpendicular to its neutral axis, as a function of its shape. The polar second moment of area provides insight into a beam's resistance to torsional deflection, due to an applied moment parallel to its cross-section, as a function of its shape.

Different disciplines use the term moment of inertia (MOI) to refer to different moments. It may refer to either of the planar second moments of area (often or with respect to some reference plane), or the polar second moment of area (, where r is the distance to some reference axis). In each case the integral is over all the infinitesimal elements of area, dA, in some two-dimensional cross-section. In physics, moment of inertia is strictly the second moment of mass with respect to distance from an axis: , where r is the distance to some potential rotation axis, and the integral is over all the infinitesimal elements of mass, dm, in a three-dimensional space occupied by an object Q. The MOI, in this sense, is the analog of mass for rotational problems. In engineering (especially mechanical and civil), moment of inertia commonly refers to the second moment of the area.

Definition

The second moment of area for an arbitrary shape R with respect to an arbitrary axis ( axis is not drawn in the adjacent image; is an axis coplanar with x and y axes and is perpendicular to the line segment ) is defined as where

- is the infinitesimal area element, and

- is the distance from the axis.

For example, when the desired reference axis is the x-axis, the second moment of area (often denoted as ) can be computed in Cartesian coordinates as

The second moment of the area is crucial in Euler–Bernoulli theory of slender beams.

Product moment of area

More generally, the product moment of area is defined as

Parallel axis theorem

It is sometimes necessary to calculate the second moment of area of a shape with respect to an axis different to the centroidal axis of the shape. However, it is often easier to derive the second moment of area with respect to its centroidal axis, , and use the parallel axis theorem to derive the second moment of area with respect to the axis. The parallel axis theorem states where

- is the area of the shape, and

- is the perpendicular distance between the and axes.

A similar statement can be made about a axis and the parallel centroidal axis. Or, in general, any centroidal axis and a parallel axis.

Perpendicular axis theorem

Main article: Perpendicular axis theoremFor the simplicity of calculation, it is often desired to define the polar moment of area (with respect to a perpendicular axis) in terms of two area moments of inertia (both with respect to in-plane axes). The simplest case relates to and .

This relationship relies on the Pythagorean theorem which relates and to and on the linearity of integration.

Composite shapes

For more complex areas, it is often easier to divide the area into a series of "simpler" shapes. The second moment of area for the entire shape is the sum of the second moment of areas of all of its parts about a common axis. This can include shapes that are "missing" (i.e. holes, hollow shapes, etc.), in which case the second moment of area of the "missing" areas are subtracted, rather than added. In other words, the second moment of area of "missing" parts are considered negative for the method of composite shapes.

Examples

See list of second moments of area for other shapes.

Rectangle with centroid at the origin

Consider a rectangle with base and height whose centroid is located at the origin. represents the second moment of area with respect to the x-axis; represents the second moment of area with respect to the y-axis; represents the polar moment of inertia with respect to the z-axis.

Using the perpendicular axis theorem we get the value of .

Annulus centered at origin

Consider an annulus whose center is at the origin, outside radius is , and inside radius is . Because of the symmetry of the annulus, the centroid also lies at the origin. We can determine the polar moment of inertia, , about the axis by the method of composite shapes. This polar moment of inertia is equivalent to the polar moment of inertia of a circle with radius minus the polar moment of inertia of a circle with radius , both centered at the origin. First, let us derive the polar moment of inertia of a circle with radius with respect to the origin. In this case, it is easier to directly calculate as we already have , which has both an and component. Instead of obtaining the second moment of area from Cartesian coordinates as done in the previous section, we shall calculate and directly using polar coordinates.

Now, the polar moment of inertia about the axis for an annulus is simply, as stated above, the difference of the second moments of area of a circle with radius and a circle with radius .

Alternatively, we could change the limits on the integral the first time around to reflect the fact that there is a hole. This would be done like this.

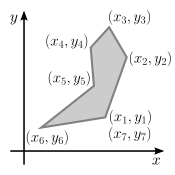

Any polygon

The second moment of area about the origin for any simple polygon on the XY-plane can be computed in general by summing contributions from each segment of the polygon after dividing the area into a set of triangles. This formula is related to the shoelace formula and can be considered a special case of Green's theorem.

A polygon is assumed to have vertices, numbered in counter-clockwise fashion. If polygon vertices are numbered clockwise, returned values will be negative, but absolute values will be correct.

where are the coordinates of the -th polygon vertex, for . Also, are assumed to be equal to the coordinates of the first vertex, i.e., and .

See also

- List of second moments of area

- List of moments of inertia

- Moment of inertia

- Parallel axis theorem

- Perpendicular axis theorem

- Radius of gyration

References

- Beer, Ferdinand P. (2013). Vector Mechanics for Engineers (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 471. ISBN 978-0-07-339813-6.

The term second moment is more proper than the term moment of inertia, since, logically, the latter should be used only to denote integrals of mass (see Sec. 9.11). In engineering practice, however, moment of inertia is used in connection with areas as well as masses.

- Pilkey, Walter D. (2002). Analysis and Design of Elastic Beams. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-471-38152-5.

- Beer, Ferdinand P. (2013). "Chapter 9.8: Product of inertia". Vector Mechanics for Engineers (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 495. ISBN 978-0-07-339813-6.

- Hibbeler, R. C. (2004). Statics and Mechanics of Materials (Second ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-028127-1.

- Beer, Ferdinand P. (2013). "Chapter 9.6: Parallel-axis theorem". Vector Mechanics for Engineers (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 481. ISBN 978-0-07-339813-6.

- Hally, David (1987). Calculation of the Moments of Polygons (PDF) (Technical report). Canadian National Defense. Technical Memorandum 87/209. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 23, 2020.

- Obregon, Joaquin (2012). Mechanical Simmetry. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4772-3372-6.

- Steger, Carsten (1996). "On the Calculation of Arbitrary Moments of Polygons" (PDF). S2CID 17506973. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-03.

- Soerjadi, Ir. R. "On the Computation of the Moments of a Polygon, with some Applications".

(for an axis that lies in the plane of the area) or with a

(for an axis that lies in the plane of the area) or with a  (for an axis perpendicular to the plane). In both cases, it is calculated with a

(for an axis perpendicular to the plane). In both cases, it is calculated with a  or

or  with respect to some reference plane), or the polar second moment of area (

with respect to some reference plane), or the polar second moment of area ( , where r is the distance to some reference axis). In each case the integral is over all the infinitesimal elements of area, dA, in some two-dimensional cross-section. In

, where r is the distance to some reference axis). In each case the integral is over all the infinitesimal elements of area, dA, in some two-dimensional cross-section. In  , where r is the distance to some potential rotation axis, and the integral is over all the infinitesimal elements of mass, dm, in a three-dimensional space occupied by an object Q. The MOI, in this sense, is the analog of mass for rotational problems. In engineering (especially mechanical and civil), moment of inertia commonly refers to the second moment of the area.

, where r is the distance to some potential rotation axis, and the integral is over all the infinitesimal elements of mass, dm, in a three-dimensional space occupied by an object Q. The MOI, in this sense, is the analog of mass for rotational problems. In engineering (especially mechanical and civil), moment of inertia commonly refers to the second moment of the area.

(

( ) is defined as

) is defined as

where

where

is the infinitesimal area element, and

is the infinitesimal area element, and (often denoted as

(often denoted as  ) can be computed in

) can be computed in

axis different to the

axis different to the  , and use the parallel axis theorem to derive the second moment of area with respect to the

, and use the parallel axis theorem to derive the second moment of area with respect to the  where

where

is the area of the shape, and

is the area of the shape, and is the perpendicular distance between the

is the perpendicular distance between the  axis and the parallel centroidal

axis and the parallel centroidal  axis. Or, in general, any centroidal

axis. Or, in general, any centroidal  axis and a parallel

axis and a parallel  axis.

axis.

to

to  .

.

and height

and height  whose

whose

, and inside radius is

, and inside radius is  . Because of the symmetry of the annulus, the

. Because of the symmetry of the annulus, the  axis by the method of composite shapes. This polar moment of inertia is equivalent to the polar moment of inertia of a circle with radius

axis by the method of composite shapes. This polar moment of inertia is equivalent to the polar moment of inertia of a circle with radius  with respect to the origin. In this case, it is easier to directly calculate

with respect to the origin. In this case, it is easier to directly calculate  , which has both an

, which has both an

integral the first time around to reflect the fact that there is a hole. This would be done like this.

integral the first time around to reflect the fact that there is a hole. This would be done like this.

, notice point "7" is identical to point 1.

, notice point "7" is identical to point 1.  vertices, numbered in counter-clockwise fashion. If polygon vertices are numbered clockwise, returned values will be negative, but absolute values will be correct.

vertices, numbered in counter-clockwise fashion. If polygon vertices are numbered clockwise, returned values will be negative, but absolute values will be correct.

are the coordinates of the

are the coordinates of the  -th polygon vertex, for

-th polygon vertex, for  . Also,

. Also,  are assumed to be equal to the coordinates of the first vertex, i.e.,

are assumed to be equal to the coordinates of the first vertex, i.e.,  and

and  .

.