A spoon (UK: /ˈspuːn/, US: /ˈspun/ SPOON) is a utensil consisting of a shallow bowl (also known as a head), oval or round, at the end of a handle. A type of cutlery (sometimes called flatware in the United States), especially as part of a place setting, it is used primarily for transferring food to the mouth (eating). Spoons are also used in food preparation to measure, mix, stir and toss ingredients and for serving food. Present day spoons are made from metal (notably flat silver or silverware, plated or solid), wood, porcelain or plastic. There are many different types of spoons made from different materials by different cultures for different purposes and food.

Terminology

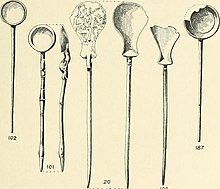

The spoon consists of a bowl and a handle. A handle in the shape of a slender stick is frequently called a stem. The stem can end in a sharp point or be crowned with a knop, a decorative knob. The knop-top spoons with a variety of knop shapes described by colorful terms like "acorn", "writhen-end" (spiral ornament on a ball), "maidenhead" (a bust), "diamond point," "apostle" were particularly popular in England in the 14th to 17th centuries.

The name spoon came from Old English spon, 'chip'.

History

Preserved examples of various forms of spoons used by the ancient Egyptians include those composed of ivory, flint, slate and wood, many of them carved with religious symbols. During the Neolithic Ozieri civilization in Sardinia, ceramic ladles and spoons were already in use. In Shang dynasty China, spoons were made of bone. Early bronze spoons in China were designed with a sharp point, and may have also been used as cutlery. The spoons of the Greeks and Romans were chiefly made of bronze and silver and the handle usually takes the form of a spike or pointed stem. There are many examples in the British Museum from which the forms of the various types can be ascertained, the chief points of difference being found in the junction of the bowl with the handle. The ancient Greeks called the spoon mystron (μύστρον), and they also used pieces of bread scooped out in the shape of a spoon, which they called, mystile (μυστίλη).

A 2024 study by archaeologist Andrzej Kokowski and biologists from Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin, Poland, identified 241 small, spoon-shaped objects at 116 archaeological sites across Scandinavia, Germany, and Poland, dating back to the Roman era. These sites primarily consisted of marshes and graves. The study proposes that these objects, often found alongside items associated with warfare and featuring a small disk 10-20 millimeters in diameter, were likely used to administer drugs, especially stimulants, before battles. Germanic peoples of the era had access to various substances with potential medicinal or psychoactive properties, including poppy, hops, hemp, henbane, belladonna, and certain fungi.

In the early Muslim world, spoons were used for eating soup. Medieval spoons meant for domestic use were commonly made of cow horn or wood, but brass, pewter, and latten spoons appear to have been common in about the 15th century. The full descriptions and entries relating to silver spoons in the inventories of the royal and other households point to their special value and rarity. The earliest English reference appears to be in a will of 1259. In the wardrobe accounts of Edward I for the year 1300 some gold and silver spoons marked with the fleur-de-lis, the Paris mark, are mentioned. One of the most interesting medieval spoons is the Coronation Spoon used in the anointing of the English and later British sovereign; this 12th-century object is the oldest surviving item in the British royal regalia.

The sets of Apostle Spoons, popular as christening presents in Tudor times, the handles of which terminate in heads or busts of the apostles, are a special form to which antiquarian interest attaches. The earlier English spoon-handles terminate in an acorn, plain knob or a diamond; at the end of the 16th century, the baluster and seal ending becomes common, the bowl being fig-shaped. During The Restoration, the handle becomes broad and flat, the bowl is broad and oval and the termination is cut into the shape known as the hind's foot.

In the first quarter of the 18th century, the bowl becomes narrow and elliptical, with a tongue or rat's tail down the back, and the handle is turned up at the end. The modern form, with the tip of the bowl narrower than the base and the rounded end of the handle turned down, came into use about 1760.

-

Spoon engraved in reindeer antler, Magdalenian c. 17,000 – c. 12,000 BCE

Spoon engraved in reindeer antler, Magdalenian c. 17,000 – c. 12,000 BCE

-

Bronze spoon, Shang dynasty

Bronze spoon, Shang dynasty

-

Roman spoons from the Hoxne hoard, c. 4-5th century CE

Roman spoons from the Hoxne hoard, c. 4-5th century CE

-

Jade spoon, Mughal dynasty, India

-

Wooden spoon found on board the 16th century carrack Mary Rose

-

Native American Yurok spoons, 19th century

Native American Yurok spoons, 19th century

-

Achaemenid spoon (400 BC)

Achaemenid spoon (400 BC)

Types and uses

See also: List of types of spoons

Spoons are used primarily for eating liquid or semi-liquid foods, such as soup, stew or ice cream, and very small or powdery solid items which cannot be easily lifted with a fork, such as rice, sugar, cereals and green peas. In Southeast Asia, spoons are the primary utensil used for eating; forks are used to push foods such as rice onto the spoon as well as their western usage for piercing the food.

Spoons are also widely used in cooking and serving. In baking, batter is usually thin enough to pour or drop from a spoon; a mixture of such consistency is sometimes called "drop batter". Rolled dough dropped from a spoon to a cookie sheet can be made into rock cakes and other cookies, while johnnycake may be prepared by dropping spoonfuls of cornmeal onto a hot greased griddle.

A spoon is similarly useful in processing jelly, sugar and syrup. A test sample of jelly taken from a boiling mass may be allowed to slip from a spoon in a sheet, in a step called "sheeting". At the "crack" stage, syrup from boiling sugar may be dripped from a spoon, causing it to break with a snap when chilled. When boiled to 240 °F. and poured from a spoon, sugar forms a filament, or "thread". Hot syrup is said to "pearl" when it forms such a long thread without breaking when dropped from a spoon.

Used for stirring, a spoon is passed through a substance with a continued circular movement for the purpose of mixing, blending, dissolving, cooling, or preventing sticking of the ingredients. Mixed drinks may be "muddled" by working a spoon to crush and mix ingredients such as mint and sugar on the bottom of a glass or mixer. Spoons are employed for mixing certain kinds of powder into water to make a sweet or nutritious drink. A spoon may also be employed to toss ingredients by mixing them lightly until they are well coated with a dressing.

For storage, spoons and knives were sometimes placed in paired knife boxes, which were often ornate wooden containers with sloping tops, used especially during the 18th century. On the table, an ornamental utensil called a nef, shaped like a ship, might hold a napkin, knife and spoon.

-

Spoon with a special tip for kiwifruits or melons

Spoon with a special tip for kiwifruits or melons

-

Spoons for salad

Spoons for salad

-

Cold breakfast cereal held in a dessert spoon

Cold breakfast cereal held in a dessert spoon

-

Stainless steel bouillon spoon

Stainless steel bouillon spoon

Language and culture

Spoons are mentioned in the Bible (KJV): God in the Book of Exodus tells Moses to make for Tabernacle, among other things, spoons of gold.

The expression "born with a silver spoon in his mouth" (born into privilege) formed due to the mediaeval custom of gifting a "baptismal spoon" to a child; well-to-do families were able to afford spoons made of precious metals.

Spoons can be used as a musical instrument.

To spoon-feed oneself or another can simply mean to feed by means of a spoon. Metaphorically, however, it often means to present something to a person or group so thoroughly or wholeheartedly as to preclude the need for independent thought, initiative or self-reliance on the part of the recipient; or to present information in a slanted version, with the intent to preclude questioning or revision. Someone who accepts passively what has been offered in this way is said to have been spoon-fed.

A spoonful is the amount of material a spoon contains or can contain. Itis used as a standard unit of measure for volume in cooking, where it normally signifies a teaspoonful. It is abbreviated coch or cochl, from Latin: cochlearium, a small Roman spoon. "Teaspoonful" is often used in a similar way to describe the dosage for over the counter medicines. Dessert spoonful and tablespoonful may also be found in drink and food recipes. A teaspoon holds about 5 ml and a tablespoon about 15 ml.

The souvenir spoon generally exists solely as a decorative object commemorating an event, place, or special date.

Manufacture

See also: Alloys of silver used in jewellery and silverwareFor machine-made spoons, the basic shape is cut out from a sheet of sterling silver, nickel silver alloy or stainless steel. The bowl is cross rolled between two pressurized rollers to produce a thinner section. The handle section is also rolled to produce the width required for the top end. The blank is then cropped to the required shape, and two dies are used to apply the pattern to the blank. The flash is then removed using a linisher, and the bowl is formed between two dies and bent.

To make a spoon the traditional way by way of hand forging, a bar of silver is marked up to the correct proportions for the bowl and handle.

It is then heated until red hot and held in tongs, and using the hammer and anvil, beaten into shape. The tip of the bar is pointed to form the tip of the bowl, then hammered to form the bowl. If a heel is to be added, a section down the centre is left thicker. The edges of the bowl and the tip of the spoon are left thicker as this is where most of the thickness is needed. The handle is then started and hammered out to length going from thick at the neck and gradually tapering down in thickness giving a balanced feel. During this process, the piece becomes very hard and has to be annealed several times, then worked again until the final shape is achieved.

The bowl is filed to shape, often using a metal template. The bowl is then formed using a tin cake and spoon stake. The molten tin is poured around the spoon stake and left to harden. The handle is then bent down to 45 degrees, and the spoon is hammered into the tin using the spoon stake and a heavy hammer, to form the bowl. The bend in the handle is then adjusted to match the other spoons in the set so that it sits correctly on the table. The bowl is then filed level, a process called striking off. The surfaces are filed, first with a rough file to remove the fire stain from the surface, then with a smooth file. It is then buffed to remove any file marks and fire stain from inside the bowl and is polished to the desired finish.

Derivatives

Both the spork and the sporf are derived from the spoon: they combine the bowl of the spoon with the tines of the fork and with both tines and the cutting edge of the knife, respectively.

See also

- Cutlery

- List of types of spoons

- Montreal–Philippines cutlery controversy

- Scoop (utensil)

- Spoon bending

- Spoon theory

Notes

- Forgeng, Singman & McLean 1995, p. 167.

- Veitgh 1923, p. 121.

- Von Drachenfels 2000, p. 186.

- "spoon". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Spoon". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 733.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Spoon". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 733.

- Joseph Needham (2000). Science and Civilisation in China: Fermentations and Food Science. Cambridge University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-521-65270-4.

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Cena

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Mystile

- Gruyter, De (2024-12-02). "Barbarian warriors in Roman times used stimulants in battle, findings suggest". Phys.org. Retrieved 2024-12-05.

- Lindsay, James E. (2005). Daily Life in the Medieval Islamic World. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 128. ISBN 0-313-32270-8.

- "South China Seas Culture & Cuisine". www.satayusa.com.

- "UKTV Food: Recipes: Southeast Asian cuisine".

- Cech, Mary (2013-05-14). Savory Baking: 75 Warm and Inspiring Recipes for Crisp, Savory Baking. Chronicle Books. ISBN 9781452100234.

- Lincoln, Mary Johnson (1915). The School Kitchen Textbook: Lessons in Cooking and Domestic Science for the Use of Elementary Schools. Little, Brown. p. 242.

batter is usually thin enough to pour or drop from a spoon called drop batter.

- Ex 25:29

- ^ Von Drachenfels 2000, p. 187.

References

- Bednersh, Wayne. Collectible Souvenir Spoons: The Grand Tour. Collector Books, 2000. ISBN 978-1-57432-189-0.

- Rainwater, Dorothy. Spoons From Around the World. New York: Shiffer Publishing, 1992. ISBN 978-0-88740-425-2.

- Spark, Nick. Spoons West! Fred Harvey, the Navajo, and the Souvenir Spoons of the West 1890-1941. Los Angeles, California: Periscope Film, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9786388-9-4.

- Forgeng, Jeffrey L.; Singman, Jeffrey L.; McLean, Will (1995). "Food and Drink". Daily Life in Chaucer's England. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-313-29375-7. OCLC 1170051340.

- Veitgh, Henry Newton (October 1923). "Spoons Of Old English Plate". International Studio. LXXVIII (317): 121–124.

- Jackson, Charles James (1911). "The spoon and its history: Its form, material, and development". An Illustrated History of English Plate, Ecclesiastical and Secular: In which the Development of Form and Decoration in the Silver and Gold Work of the British Isles, from the Earliest Known Examples to the Latest of the Georgian Period, is Delineated and Described, Volume 2. "Country life," limited. pp. 470–537. OCLC 1074655150.

- Von Drachenfels, Suzanne (8 November 2000). "The Spoon". The Art of the Table: A Complete Guide to Table Setting, Table Manners, and Tableware. Simon and Schuster. pp. 186–195. ISBN 978-0-684-84732-0.

External links

- The History of Eating Utensils - Spoons. Rietz Collection of Food Technology.

- The Making of a Spoon, Georgian style. Online Encyclopedia of Silver Marks, Hallmarks & Makers' Marks. Illustrated article on the hand forging of a spoon.

- Jackson, C. J. (1892). "The Spoon and its history". Archaeologia. 53: 107–146. doi:10.1017/S0261340900011231.

- History of Spoon - Eating Utensils

Categories: