Islamic finance products, services and contracts are financial products and services and related contracts that conform with Sharia (Islamic law). Islamic banking and finance has its own products and services that differ from conventional banking. These include Mudharabah (profit sharing), Wadiah (safekeeping), Musharakah (joint venture), Murabahah (cost plus finance), Ijar (leasing), Hawala (an international fund transfer system), Takaful (Islamic insurance), and Sukuk (Islamic bonds).

Sharia prohibits riba, or usury, defined as interest paid on all loans of money (although some Muslims dispute whether there is a consensus that interest is equivalent to riba). Investment in businesses that provide goods or services considered contrary to Islamic principles (e.g. pork or alcohol) is also haraam ("sinful and prohibited").

As of 2014, around $2 trillion in financial assets, or 1 percent of total world assets, was Sharia-compliant, concentrated in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, Iran, and Malaysia.

Principles

To be consistent with the principles of Islamic law (Shariah) and guided by Islamic economics, the contemporary movement of Islamic banking and finance prohibits a variety of activities:

- Paying or charging interest. "All forms of interest are riba and hence prohibited". Islamic rules on transactions (known as Fiqh al-Muamalat) have been created to prevent use of interest.

- Investing in businesses involved in activities that are forbidden (haraam). These include things such as selling alcohol or pork, or producing media such as gossip columns or pornography.

- Charging extra for late payment. This applies to murâbaḥah or other fixed payment financing transactions, although some authors believe late fees may be charged if they are donated to charity, or if the buyer has "deliberately refused" to make a payment.

- Maisir. This is usually translated as "gambling" but used to mean "speculation" in Islamic finance. Involvement in contracts where the ownership of a good depends on the occurrence of a predetermined, uncertain event in the future is maisir and forbidden in Islamic finance.

- Gharar. Gharar is usually translated as "uncertainty" or "ambiguity". Bans on both maisir and gharar tend to rule out derivatives, options and futures. Islamic finance supporters (such as Mervyn K. Lewis and Latifa M. Algaoud) believe these involve excessive risk and may foster uncertainty and fraudulent behaviour such as are found in derivative instruments used by conventional banking.

- Engaging in transactions lacking "'material finality'. All transactions must be "directly linked to a real underlying economic transaction", which generally excludes "options and most other derivatives".

Money earned from the most common type of Islamic financing—debt-based contracts—"must" come "from a tangible asset that one owns and thus has the right to sell—and in financial transactions it demands that risk be shared." Money cannot be made from money. as "it is only a medium of exchange." Risk and return on distribution to participants should be symmetrical so that no one benefits disproportionately from the transaction. Other restrictions include

- A board of shariah experts is to supervise and advise each Islamic bank on the propriety of transactions to "ensure that all activities are in line with Islamic principles". (Interpretations of Shariah may vary by country, with it being most strict in Sudan somewhat less in Turkey or Arab countries, less still in Malaysia, whose interpretation is in turn more strict than the Islamic Republic of Iran. Mahmud el-Gamal found interpretations most strict in Sudan and least in Malaysia.)

Islamic banking and finance has been described as having the "same purpose" (Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance), or having the same "basic objective" (Mohamed Warsame), as conventional banking but operating in accordance with the rules of shariah law.

Benefits that will follow from banning interest and obeying "divine injunctions" include an Islamic economy free of "imbalances" (Taqi Usmani)—concentration of "wealth in the hands of the few", or monopolies which paralyze or hinder market forces, etc.—a "move towards economic development, creation of the value added factor, increased exports, less imports, job creation, rehabilitation of the incapacitated and training of capable elements" (Saleh Abdullah Kamel).

Other describe these benefits (or similar ones) as "principals" or "objectives" of Islamic finance. Nizam Yaquby, for example declares that the "guiding principles" for Islamic finance include: "fairness, justice, equality, transparency, and the pursuit of social harmony". Some distinguish between sharia-compliant finance and a more holistic, pure and exacting sharia-based finance. "Ethical finance" has been called necessary, or at least desirable, for Islamic finance, as has a "gold-based currency". Zubair Hasan argues that the objectives of Islamic finance as envisaged by its pioneers were "promotion of growth with equity ... the alleviation of poverty ... a long run vision to improve the condition of the Muslim communities across the world."

- Criticism

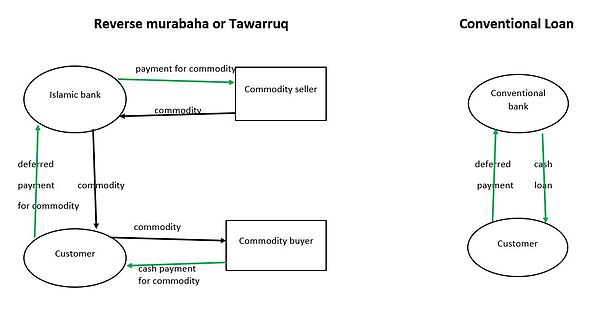

Modernist/Minimalist critic Feisal Khan argues that in many ways Islamic finance has not lived up to its defining characteristics. Risk-sharing is lacking because profit and loss sharing modes are so infrequently used. Underlying material transactions are also missing in such transactions as "tawarruq, commodity murabahas, Malaysian Islamic private debt securities, and Islamic short-sales". Exploitation is involved when high fees are charged for "doing nothing more substantial than mimicking conventional banking /finance products". Haram activities are not avoided when banks (following the customary practice) simply take the word of clients/financees/borrowers that they will not use funds for unIslamic activities.

Others (such as convert Umar Ibrahim Vadillo) agree that the Islamic banking movement has failed to follow the principles of shariah law, but call for greater strictness and greater separation from the non-Muslim world.

Overview of products, contracts, etc.

Banking makes up most of the Islamic finance industry. Banking products are often classified in one of three broad categories, two of which are "investment accounts":

- Profit and loss sharing modes—musharakah and mudarabah—where financier and the user of finance share profits and losses, are based on "contracts of partnership".

- "Asset-backed financing", (also known as trade-based financing" or "non-PLS financing"), "debt-like instruments" which are based on "debt-based contracts" or "contracts of exchange". They are structured as sales and allow for "the transfer of a commodity for another commodity, the transfer of a commodity for money, or the transfer of money for money". They involve the financing "purchase and hire of goods or assets and services", and like conventional loans repayment is deferred, increased, and made on a "fixed-return basis". Unlike conventional loans, the fixed return is called "profit" or "markup", not "interest". According to Feisal Khan, "virtually every" Islamic banking advocate argues that these "non-non-participatory" forms of finance are acceptable only as "an interim measure" as Islamic banking develops, or for situations such as small and personal loans where participatory financing is not practical. Faleel Jamaldeen states that debt-based contracts are often used to finance not-so-minor purchases (homes, cars, etc.) for bank customers. These instruments include mark-up (murabaha), leasing (ijara), cash advances for the purchase of agricultural produce (salam), and cash advances for the manufacture of assets (istisna').

the third category consists of

- Modes based on contracts of safety and security, include safe-keeping contracts (wadi’ah) for current deposits (called checking accounts in the US), and agency contracts (wakalah). Current account deposits are regarded as trusts or safe-keeping and offer the depositors safety of their money against the bank's guarantee to return their funds on demand. (A current account the customer earns no return, but sources do not agree over whether the bank is allowed to invest the account funds. According to one report, in practice no examples of 100 percent reserve banking are known to exist.)

- Non-banking finance

Islamic non-banking finance has grown to encompass a wide range of services, but as of 2013, banking still dominates and represented about four-fifths of total assets in Islamic finance. The sukuk market is also a fast-growing segment with assets equivalent to about 15 percent of the industry. Other services include leasing, equity markets, investment funds, insurance (takaful), and microfinance.

These products—and Islamic finance in general—are based on Islamic commercial contracts (aqad i.e. a commitment between two parties) and contract law, with products generally named after contracts (e.g. mudaraba) though they may be combinations of more than one type of contract.

Profit and loss sharing

Further information: Profit and loss sharingWhile the original Islamic banking proponents hoped profit-loss sharing (PLS) would be the primary mode of finance replacing interest-based loans, long-term financing with profit-and-loss-sharing mechanisms is "far riskier and costlier" than the long term or medium-term lending of the conventional banks, according to critics such as economist Tarik M. Yousef.

Yousef and other observers note that musharakah and mudarabah financing have "declined to almost negligible proportions". In many Islamic banks asset portfolios, short term financing, notably murabaha and other debt-based contracts account for the great bulk of their investments.

==zcnj.jose[h/

Musharakah (joint venture)

Musharakah is a relationship between two or more parties that contribute capital to a business and divide the net profit and loss pro rata. Unlike mudarabah, there may be more than two partners and all the providers of capital are entitled (but not required) to participate in management. Like mudarabah, the profit is distributed among the partners in pre-agreed ratios, while the loss is borne by each partner in proportion to respective capital contributions.

This mode is often used in investment projects, letters of credit, and the purchase or real estate or property. Musharakah may be "permanent" (often used in business partnerships) or "diminishing" (often used in financing major purchases, see below). In Musharaka business transactions, Islamic banks may lend their money to companies by issuing "floating rate interest" loans, where the floating rate is pegged to the company's individual rate of return, so that the bank's profit on the loan is equal to a certain percentage of the company's profits.

Use of musharaka (or at least permanent musharakah) is not great. In Malaysia, for example, the share of musharaka financing declined from 1.4 percent in 2000 to 0.2 percent in 2006

Diminishing Musharaka

A popular type of financing for rydamajor purchases—particularly housing—is Musharaka al-Mutanaqisa (literally "diminishing partnership"). A musharaka al-mutanaqisa agreement actually also involves two other Islamic contracts besides partnership—ijarah (leasing by the bank of its share of the asset to the customer) and bay' (gradual sales of the bank's share to the customer).

In this mode of finance the bank and the purchaser/customer start with joint ownership of the purchased asset—the customer's sharing being their down-payment, the banks share usually being much larger. The customer leases/rents the asset from the bank—bank assessing (at least in theory) an imputed rent for use of the asset—while gradually paying off the cost of the asset while the bank's share diminishes to nothing.

If default occurs, both the bank and the borrower receive a proportion of the proceeds from the sale of the property based on each party's current equity.

This method allows for floating rates according to the current market rate such as the BLR (base lending rate), especially in a dual-banking system like in Malaysia. However, at least one critic (M. A. El-Gamal) complains that this violates the sharia principle that banks must charge 'rent' (or lease payment) based on comparable rents for the asset being paid off, not "benchmarked to commercial interest rate".

Asset-backed financing

Asset-backed or debt-type instruments (also called contracts of exchange) are sales contracts that allow for the transfer of a commodity for another commodity, the transfer of a commodity for money, or the transfer of money for money. They include Murabaha, Musawamah, Salam, Istisna’a, and Tawarruq.

Murâbaḥah

Main article: MurabahahMurabaha is an Islamic contract for a sale where the buyer and seller agree on the markup (profit) or "cost-plus" price for the item(s) being sold. In Islamic banking it has become a term for financing where the bank buys some good (home, car, business supplies, etc.) at the request of a customer and marks up the price of that good for resale to the customer (with the difference clearly stated to the customer) in exchange for allowing the customer/buyer to defer payment. (A contract with deferred payment is known as bai-muajjal in Islamic jurisprudence.)

Murabaha has also come to be "the most prevalent" or "default" type of Islamic finance. Most of the financing operations of Islamic banks and financial institutions use murabahah, according to Islamic finance scholar Taqi Uthmani, (One estimate is that 80% of Islamic lending is by Murabahah.) This is despite the fact that (according to Uthmani) "Shari‘ah supervisory Boards are unanimous on the point that are not ideal modes of financing", and should be used when more preferable means of finance—"musharakah, mudarabah, salam or istisna'—are not workable for some reasons".

Murabahah is somewhat similar to a conventional mortgage transaction (for homes) or hire purchase/"installment plan" arrangements (for furniture or appliances), in that instead of lending a buyer money to purchase an item and having the buyer pay the lender back, the financier buys the item itself and re-sells it to the customer who pays the financier in installments. Unlike conventional financing, the bank is compensated for the time value of its money in the form of "profit" not interest, and any penalties for late payment go to charity, not to the financier.

Economists have questioned whether Murabahah is "economically indistinguishable from traditional, debt- and interest-based finance." Since "there is principal and a payment plan, there is an implied interest rate", based on conventional banking interest rates such as LIBOR. Others complain that in practice most "murabaḥah" transactions are merely cash-flows between banks, brokers and borrowers, with no actual buying or selling of commodities.

- Bai' muajjal, also called bai'-bithaman ajil, or BBA, (also known as credit sale or deferred payment sale)

In Bai' muajjal (literally "credit sale", i.e. the sale of goods on a deferred payment basis), the financier buys the equipment or goods requested by the client, then sells the goods to the client for an agreed price, which includes a mark-up (profit) for the bank and is paid either in installments over a pre-agreed period or in a lump sum at a future date. The contract must expressly mention cost of the commodity and the margin of profit is mutually agreed. Bia'muajjal was introduced in 1983 by Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad.

Because in Islamic finance the markup in murabahah is charged in exchange for deferred payment, bai' muajjal and murabahah are often used interchangeably, (according to Hans Visser), or "in practice ... used together" (according to Faleel Jamaldeen). However, according to another (Bangladeshi) source, Bai' muajjal differs from Murabahah in that the client, not the bank, is in possession of and bear the risk for the goods being purchased before completion of payment. And according to a Malaysian source, the main difference between BBA (short for bai'-bithaman ajil) and murabaha—at least as practiced in Malaysia—is that murabaha is used for medium and short term financing and BBA for longer term.

- Bai' al 'inah (sale and buy-back agreement)

Bai' al inah (literally, "a loan in the form of a sale"), is a financing arrangement where the financier buys some asset from the customer on spot basis, with the price paid by the financier constituting the "loan". Subsequently, the asset is sold back to the customer who pays in installments over time, essentially "paying back the loan". Since loaning of cash for profit is forbidden in Islamic Finance, there are differences of opinion amongst the scholars on the permissibility of Bai' al 'inah. According to the Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance, it "serves as a ruse for lending on interest", but Bai' al inah is practised in Malaysia and similar jurisdictions.

Bai al inah is not accepted in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) but in 2009 the Malaysian Court of Appeals upheld it as a shariah-compliant technique. This was a demonstration of "the philosophical differences" in Shariah between these "two centers of Islamic finance", according to Thomson Reuters Practical Law.

Musawamah

A Musawamah (literally "bargaining") contract is used if the exact cost of the item(s) sold to the bank/financier either cannot be or is not ascertained. Musawamah differs from Murabahah in that the "seller is not under the obligation to reveal his cost or purchase price", even if they do know it. Musawamah is the "most common" type of "trading negotiation" seen in Islamic commerce.

Istisna

Istisna (also Bia Istisna or Bai' Al-Istisna) and Bia-Salam are "forward contracts" (customized contracts between two parties to buy or sell an asset at a specified price on a future date). They are also contracts made before the objects of sale comes into existence, and should be as detailed as possible to avoid uncertainty.

Istisna (literally, a request to manufacture something) is a "forward contract on a project" and unlike Bia-Salam can only be a contract for something manufactured, processed, or constructed, which would never exist were it not for the contract to make it. Also unlike bia salam,

- The price need not be paid in full in advance. Financing payments may be made in stages to purchase raw materials for manufacturing, construction materials for construction of a building. When the product/structure is finished and sold, the bank can be repaid.

- The contract may be canceled unilaterally before the manufacturer or builder starts work.

- It is not necessary that the time of delivery be fixed.

Examples of istisna in the Islamic finance world include:

- projects and residential properties financed by the Kuwait Finance House under construction as of 2012.

- the Barzan project, the "biggest financing operation in the energy sector" carried out by QatarEnergy uses Istisna and Ijara and as of 2013, had US$500M "earmarked" for it.

Bai Salam

Like istisna, Bai Salam (also Bai us salam or just salam) is a forward contract in which advance payment is made for goods in the future, with the contract spelling out the nature, price, quantity, quality, and date and place of delivery of the good in precise enough detail "to dismiss any possible conflict". Salam contracts predate istisna and were designed to fulfill the needs of small farmers and traders. The objects of the sale maybe of any type—except gold, silver, or currencies based on these metals. Islamic banks often use "parallel" salam contracts and acting as a middleman. One contract is made with a seller and another with a purchaser to sell the good for a higher price. Examples of banks using these contracts are ADCB Islamic Banking and Dubai Islamic Bank.

- Basic features and conditions of a proper salam contract

- A salam transaction must have the buyer paying the purchase price to the seller (the small farmer or trader, etc. being financed) in full at the time of sale.

- Salam cannot specify that a particular commodity or a product come from a particular place—wheat from a particular field, or fruit from a particular tree as this would introduce excessive uncertainty (gharar) to the contract. (The specified crop or fruit might be ruined or destroyed before delivery.)

- To avoid dispute, the quality and quantity (whether weight or volume) of the commodity purchased must be fully specified leaving no ambiguity.

- The exact date and place of delivery must be specified.

- Any exchange of gold, silver, wheat, barley, date, or salt on a deferred basis in salam is a violation of riba al-fadl and forbidden.

- Salam is a preferred financing structure and carries higher order of shariah compliance than contracts such as Murahabah or Musawamah.

Ijarah

Main article: IjarahIjarah, (literally "to give something on rent") is a term of Islamic jurisprudence, and a product in Islamic banking and finance resembling rent-to-own. In traditional fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), it means a contract for the hiring of persons or services or "usufruct" of a property generally for a fixed period and price. In Islamic finance, al Ijarah usually refers to a leasing contract of property (such as plant, office automation, motor vehicle), which is leased to a client for stream of rental and purchase payments, ends with a transfer of ownership to the lessee, and otherwise follows Islamic regulations. Unlike a conventional lease, the financing party of a sharia-compliant Ijara must buy the asset customer wants to lease and take on "some of the commercial risks (such as damage to or loss of the asset) more usually associated with operating leases". There are several types of ijarah:

- Ijarah thumma al bai' (hire purchase)

Ijarah thumma al bai' (literally "renting/hiring/leasing followed by sale") involves the customer renting/hiring/leasing a good and agreeing to purchase it, paying both the lease/rental fee and the purchase price in installments so that by the end of the lease it owns the good free and clear. This involves two Islamic contracts (very much like "Diminishing Musharaka" above):

- an Ijarah that outlines the terms for leasing or renting over a fixed period;

- a Bai that outlines the terms for a sale to be completed by the end of the term of the Ijarah.

It is very important from the standpoint of shariah law for the Ijarah and Bai not to be combined, but to be two separate contracts. An example would be in an automobile financing facility, a customer enters into the first contract and leases the car from the owner (bank) at an agreed amount over a specific period. When the lease period expires, the second contract comes into effect, which enables the customer to purchase the car at an agreed price. (This type of transaction is similar to the contractum trinius, a legal maneuver used by European bankers and merchants during the Middle Ages to sidestep the Church's prohibition on interest bearing loans. In a contractum, two parties would enter into three (trinius) concurrent and interrelated legal contracts, the net effect being the paying of a fee for the use of money for the term of the loan. The use of concurrent interrelated contracts is also prohibited under Shariah Law.)

- Ijarah wa-iqtina

Ijarah wa-iqtina (literally, "lease and ownership" also called al ijarah muntahia bitamleek) also involves a ijarah followed by sale of leased asset to the lessee, but in an ijara wa iqtina contract the transfer of ownership occurs as soon as the lessee pays the purchase price of the asset—anytime during the leasing period. An Islamically correct ijara wa iqtina contract "rests" on three conditions:

- The lease and the transfer of ownership of the asset or the property should be recorded in separate documents.

- The agreement to transfer of ownership should not be a pre-condition to the signing of the leasing contract.

- The "promise" to transfer the ownership should be unilateral and should be binding only on the lessor.

- ijara mawsoofa bi al dhimma

In a "forward ijarah" or ijara mawsoofa bi al dhimma Islamic contract (literally "lease described with responsibility", also transliterated ijara mawsufa bi al thimma), the service or benefit being leased is well-defined, but the particular unit providing that service or benefit is not identified. Thus, if a unit providing the service or benefit is destroyed, the contract is not void. In contemporary Islamic finance, ijara mawsoofa bi al dhimma is the leasing of something (such as a home, office, or factory) not yet produced or constructed. This means the ijara mawsoofa bi al dhimma contract is combined with a Istisna contract for construction of whatever it is that will provide the service or benefit. The financier finances its making, while the party begins leasing the asset after "taking delivery" of it. While forward sales normally do not comply with sharia, it is allowed using ijarah provided rent/lease payment do not begin until after the customer takes delivery. Also required by sharia is that the asset be clearly specified, its rental rate be clearly set (although the rate may float based on the agreement of both parties).

- Ijarah challenges

Among the complaints made against ijara are that in the practice some rules are overlooked, such as ones making the lessor/financier liable in the event the property rented is destroyed because of unforeseeable circumstance (Taqi Usmani); that ijara provides weaker legal standing and consumer protection for foreclosure than conventional mortgage (Abu Umar Faruq Ahmad); and less flexibility for customers who wanting to sell property (such as a car) and repay the loan before its completion (not allowed as the customer does not own the property) (Muhammad Akram Khan).

Tawarruq

Further information: Murabaha § Bay.27_al-Tawarruq

A Tawarruq (literally "turns into silver", or "monetization") contract/product is one where a client customer can raise immediate cash to be paid back later by buying an asset that is easily saleable, paying a marked up price with deferred payment and then quickly selling the asset to raise cash. An example of this would be a customer wishing to borrow $900 in cash having their bank buy $1000 worth of some commodity (such as iron) from a supplier, and then buying the iron from the bank with an agreement that they will be given 12 months to pay the $1000 back. The customer then immediately sells the metal back to the bank for $900 cash to be paid on the spot, and the bank then resells the iron. (This would be the equivalent of borrowing $900 for a year at an interest rate of 11 percent.)

While tawarruq strongly resembles a cash loan—something forbidden under orthodox Islamic law—and its greater complexity (like bai' al inah mentioned above) mean higher costs than a conventional bank loan, proponents argue the tangible assets that underlie the transactions give it sharia compliance. However, the contract is controversial with some (also like bai' al inah). Because the buying and selling of the commodities in Tawarruq served no functional purpose, banks/financiers are strongly tempted to forgo it. Islamic scholars have noticed that while there have been "billions of dollars of commodity-based tawarruq transactions" there have not been a matching value of commodity being traded. In December 2003, the Fiqh Academy of the Muslim World League forbade tawarruq "as practiced by Islamic banks today". In 2009 another prominent juristic council, the Fiqh Academy of the OIC, ruled that "organized Tawarruq" is impermissible. Noted clerics who have ruled against it include Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya and Ibn Taymiyya. On the other hand, Faleel Jamaldeen notes that Islamic banks using Tawarruq as of 2012 include the United Arab Bank, QNB Al Islamic, Standard Chartered of United Arab Emirates, and Bank Muamalat Malaysia.

Charitable lending

Taqi Usmani insists that "role of loans" (as opposed to investment or finance) in a truly Islamic society is "very limited", and that Shariah law permits loans not as an ordinary occurrence", but only in cases of dire need".

- Qardh-ul Hasan

A shariah-compliant loan is known as Qardh-ul Hasan, (also Qard Hasan, literally: "benevolent loan" or "beneficence loan"). It is often described as an interest-free loan extended to needy people. Such loans are often made by private parties, social service agencies, or by a firm as a benefit to employees, rather than Islamic banks.

Quoting hadith, some sources insist that in addition to not "charg interest or any premium above the actual loan amount", the lender may also not gain "any advantage or benefits" from the loan, even "riding the borrower’s mule, eating at his table, or even taking advantage of the shade of his wall'".

However, other sources state that the borrower is allowed pay an extra if the extra is optional and not stipulated by contract. Some financial institutions offer products called qardh-ul hasan to lenders which charge no interest but do charge an additional management fee. There are also savings account products called qardh-ul hasan, (the "loan" being a deposit to a bank account) where the debtor (the bank) may pay an extra amount beyond the principal amount of the loan (known as a hibah, literally gift) as a token of appreciation to the creditor (depositor). These also do not (in theory) violate orthodox sharia if the extra was not promised or pre-arranged with the account/loan agreement.

Contracts of safety, security, service

These contracts are intended to help individual and business customers keep their funds safe.

Hawala

Further information: HawalaHawala (also Hiwala, Hewala, or Hundi; literally transfer or sometimes trust) is a widely used, informal "value transfer system" for transferring funds from one geographical area to another, based not on movement of cash, or on telegraph or computer network wire transfers between banks, but on a huge network of money brokers (known as "Hawaladars") located throughout the Muslim world. According to the IMF, a hawala transaction typically transfers the value of money (or debt) but not corresponding cash, from one country to another.

The hawala network operates outside of, or parallel to, traditional banking, financial channels, and remittance systems, but predates it by many centuries. In the first half of the 20th century it was gradually replaced by the instruments of the conventional banking system, but became a "substitute for many banking products", as Muslim workers began to migrate to wealthier countries to seek employment in the late 20th century, and sought ways to send money to or secure a loan taken out by their family back home. Dubai has traditionally served as a hub.

Each hawala transaction takes place entirely on the honour system, and since the system does not depend on the legal enforceability of claims, it can operate even in the absence of a legal and juridical environment. Hawaladars networks are often based on membership in the same family, village, clan, or ethnic group, and cheating is punished by effective ex-communication and "loss of honour"—leading to severe economic hardship. Hawaladars are often small traders who work at Hawala as a sideline or moonlighting operation. Hawala is based on a short term, discountable, negotiable, promissory note (or bill of exchange) called "Hundi". The Hawala debt is transferred from one debtor to another. After the debt is transferred to the second debtor, the first debtor is free from his/her obligation.

As illustrated in the box to the right, (1) a customer (A, left-hand side) approaches a hawala broker (X) in one city and gives a sum of money (red arrow) that is to be transferred to a recipient (B, right-hand side) in another, usually foreign, city. Along with the money, he usually specifies something like a password that will lead to the money being paid out (blue arrows). (2b) The hawala broker X calls another hawala broker M in the recipient's city, and informs M about the agreed password, or gives other disposition instructions of the funds. Then, the intended recipient (B), who also has been informed by A about the password (2a), now approaches M and tells him the agreed password (3a). If the password is correct, then M releases the transferred sum to B (3b), usually minus a small commission. X now basically owes M the money that M had paid out to B; thus M has to trust X's promise to settle the debt at a later date. Transactions may completed in as little as 15 minutes.

Kafala

Kafala (literally "guarantee", "joining" or "merging") is called "surety" or "guaranty" in conventional finance. A third party accepts an existing obligation and becomes responsible for fulfilling someone's liability. At least sometimes used interchangeably with himalah and za’amah. There are five "Conditions Of Kafala": Conditions of the Guaranteed, of the Guarantor, of the Object of Guarantee, of the Creditor, and of Sigah For Constituting the Contract. There are different kinds of Kafala: Kafalah Bi Al-Nafs (Physical Guarantee) and Kafalah Bi Al-Mal (Financial Guarantee), with three types of financial guarantee: kafalah bi al-dayn (guarantee for debt), kafalah bi al-taslim (guarantee for delivery), and kafalah bi al-dark.

Rahn

Rahn (collateral or pledge contract) is property pledged against an obligation. It is also used to refer to the contract that secures a financial liability, with the actual physical collateral given another name—marhoon. According to Mecelle, rahn is "to make a property a security in respect of a right of claim, the payment in full of which from the property is permitted." Hadith tradition states that the Islamic prophet Muhammad purchased food grains on credit pledging his armor as rahn.

- Types of rahn can be described in terms of who possesses them: Al-rahn al-heyazi (where the creditor holds the collateral); Al-rahn ghair al-heyazi (where the collateral is held by the debtor); Al-rahn al-musta'ar (where a third party provides the collateral).

- They can also be described by subject type: Rahn al-manqul (moveable (manqul) property, such as vehicles), Rahn ghair al-manqul (immoveable property (ghair manqul), such as land, buildings).

Wakalah

A Wakalah is a contract where a person (the principal or muwakkel) appoints a representative (the agent or wakil) to undertake transactions on his/her behalf, similar to a power of attorney. It is used when the principal does not have the time, knowledge or expertise to perform the task himself. Wakalah is a non-binding contract for a fixed fee and the agent or the principal may terminate this agency contract at any time "by mutual agreement, unilateral termination, discharging the obligation, destruction of the subject matter and the death or loss of legal capacity of the contracting parties". The agent's services may include selling and buying, lending and borrowing, debt assignment, guarantee, gifting, litigation and making payments, and are involved in numerous Islamic products like Musharakah, Mudarabah, Murabaha, Salam and Ijarah.

Types of wakalh include: general agency (wakalah 'ammah), specific agency (wakalah khassah), limited or restricted agency (wakalah muqayyadah), absolute or unrestricted agency (wakalah mutlaqah), binding wakalah (wakalah mulzimah), non-binding wakalah (wakalah ghair mulzimah), paid agency, non-paid agency, etc.

An example of the concept of wakalah is in a mudarabah profit and loss sharing contract (above) where the mudarib (the party that receives the capital and manages the enterprise) serves as a wakil for the rabb-ul-mal (the silent party that provides the capital) (although the mudarib may have more freedom of action than a strict wakil).

Deposit side of Islamic banking

From the point of view of depositors, "Investment accounts" of Islamic banks—based on profit and loss sharing and asset-backed finance—resemble "time deposits" of conventional banks. (For example, one Islamic bank—Al Rayan Bank in the UK—talks about "Fixed Term" deposits or savings accounts). In both these Islamic and conventional accounts the depositor agrees to hold the deposit at the bank for a fixed amount of time. In Islamic banking return is measured as "expected profit rate" rather than interest.

"Demand deposits" of Islamic financial institutions, which provide no return, are structured with qard al-hasana (also known as qard, see above in Charitable lending) contracts, or less commonly as wadiah or amanah contracts, according to Mohammad O. Farooq.

Restricted and unrestricted investment accounts

At least in one Muslim country with a strong Islamic banking sector (Malaysia), there are two main types of investment accounts offered by Islamic banks for those investing specifically in profit and loss sharing modes—restricted or unrestricted.

- Restricted investment accounts (RIA) enable customers to specify the investment mandate and the underlying assets that their funds may be invested in,

- unrestricted investment accounts (UIAs) do not, leaving the bank or investing institution full authority to invest funds as "it deems fit", with no restrictions as to the purpose, geographical distribution or way of investing the account's funds. In exchange for more flexible withdrawal conditions, a UIA fund may combine/commingle pools of funds that invest in diversified portfolios of underlying assets. While investment accounts can be tailored to meet a diverse range of customer needs and preferences, funds in the account are not guaranteed by Perbadanan Insurans Deposit Malaysia (PIDM) or also known as Malaysia Deposit Insurance Corporation (MDIC) internationally.

Some have complained that UIA accounts lack transparency, fail to follow Islamic banking standards, and lack of customer representation on the board of governors. Some institutions have hid poor performance of their UIAs behind "profit equalization funds" or "investment risk reserves", (which are created from profits earned during good times). "It is only when an Islamic financial institution approaches insolvency that the UIAs come to know that their deposits have eroded over the period."

Demand deposits

Islamic banks also offer "demand deposits," i.e. accounts which promise the convenience of returning funds to depositors on demand, but in return usually pay little if any return on investment and/or charge more fees.

Qard

Because demand deposits pay little if any return and (according to orthodox Islamic law) Qard al-hasana (mentioned above) loans may not have any "stipulated benefit", the Qard mode is a popular Islamic finance structure for demand deposits. In this design, qard al-hasan is defined as "deposits whose repayment in full on demand is guaranteed by the bank," with customer deposits constitute "loans" and the Islamic bank a "borrower" who pays no return (no "stipulated benefit")—in accordance with orthodox Islamic law. However, according to Islamic jurisprudence, Qard al-hasana (literally, "benevolent loan") are loans to be extended as charity to the needy who will be required to replay the loan only (at least in some definitions) "if and when ... able".

This puts account holders in the curious position—according to one skeptic (M. O. Farooq)—of making charitable loans with their deposits to multi-million or billion dollar profit-making banks, who are obliged by jurisprudence (in theory) to "repay" (i.e. to honor customers' withdrawals) only if and when able.

A further complication is that at least some conventional banks do pay a modest interest on their demand/savings deposits. In order to compete with them, Islamic banks sometimes provide an incentive of a Hibah (literally "gift") on the balance of the customers' savings accounts.

In Iran, qard al-hasanah deposit accounts are permitted to provide a number of incentives in lieu of interest, including:

- "grant of prizes in cash of kind,

- reductions in or exemptions from service charges or agents' fees payable to banks, and

- according priority in the use of banking finances."

Like dividends on shares of stock, hibah cannot be stipulated or legally guaranteed in Islam, and is not time bound. Nonetheless, one scholar (Mohammad Hashim Kamali) has complained:

"If Islamic banks routinely announce a return as a 'gift' for the account holder or offer other advantages in the form of services for attracting deposits, this would clearly permit entry of riba through the back door. Unfortunately, many Islamic banks seem to be doing precisely the same as part of their marketing strategy to attract deposits."

Wadiah and Amanah

Two other contracts sometimes used by Islamic finance institutions for pay-back-on-demand accounts instead of qard al-hasanah, are Wadi'ah (literally "safekeeping") and Amanah (literally "trust"). (The Jordan Islamic Bank uses Amanah (trust) mode for current accounts/demand deposits, the bank may only use the funds in the account at its "own risk and responsibility" and after receiving permission of the account owner.)

Sources disagree over the definition of these two contracts. "Often the same words are used by different banks and have different meanings," and sometimes wadiah and amanah are used interchangeably.

Regarding Wadiah, there is a difference over whether these deposits must be kept unused with 100 percent reserve or simply guaranteed by the bank. Financialislam.com and Islamic-banking.com talk about wadiah deposits being guaranteed for repayment but nothing about the deposit being left the untouched/uninvested. Reuters Guide to Islamic finance glossary, on the other hand, states that in wadia "... the trustee does not have rights of disposal." But according to Reuters there is a contract called Wadia yadd ad daman which is used by Islamic Banks "to accept current account deposit", and whereby the bank "guarantees repayment of the whole or part of the deposit outstanding in the account when repayment is due", and nothing about not having rights of disposal. (Two other authors, Vicary Daud Abdullah and Keon Chee, also talk of a contract with a guarantee of safe-keeping but which may be invested and not kept locked up called Wadiah yad dhamanah, apparently a different spelling of yadd ad damanh—Arabic for "guarantee").

Sources also differ on Amanah. Financialislam.com says it is a trust and an Islamic bank cannot use these funds for its operations, but Islamic-banking.com says a bank can if it "obtains authority" of depositor. Reuters talks about amanah needing to be "guarded and preserved". Abdullah and Chee, refer to amanah as a type of wadiah—Wadiah yad amanah—that is property deposited on the basis of trust or guaranteeing safe custody and must be kept in the banks vaults. (All sources note that the trustee of amanah is not liable for loss of the property entrusted if there is an "unforeseen mishap" (Abdullah and Chee), "resulting from circumstances beyond its control" (financialislam.com), or unless the trustee has been in "breach of duty" (Reuters).) (According to Mohammad Obaidullah, Amanah is "unacceptable" as an "approach to deposits", but wadiah or qard are acceptable).

Other sharia-compliant financial instruments

Sukuk (Islamic bonds)

Main article: SukukSukuk, (plural of صك Sakk), is the Arabic name for financial certificates developed as an alternative to conventional bonds. They are often referred to as "Islamic" or "sharia-compliant" bonds. Different types of sukuk are based on different structures of Islamic contracts mentioned above (murabaha, ijara, wakala, istisna, musharaka, istithmar, etc.), depending on the project the sukuk is financing.

Instead of receiving interest payments on lent money as in a conventional bond, a sukuk holder is given "(nominal) part-ownership of an asset" from which he/she receives income "either from profits generated by that asset or from rental payments made by the issuer". A sukuk security, for example, may have partial ownership of a property built by the investment company seeking to raise money from the sukuk issuance (and held in a Special Purpose Vehicle), so that sukuk holders can collect the property's profit as rent. Because they represent ownership of real assets and (at least in theory) do not guarantee repayment of initial investment, sukuk resemble equity instruments, but like a bond (and unlike equity) regular payments cease upon their expiration. However, in practice, most sukuk are "asset-based" rather than "asset-backed"—their assets are not truly owned by their Special Purpose Vehicle, and (like conventional bonds), their holders have recourse to the originator if there is a shortfall in payments.

The sukuk market began to take off around 2000 and as of 2013, sukuk represent 0.25 percent of global bond markets. The value of the total outstanding sukuk as of the end of 2014 was $294 billion, with $188 billion from Asia, and $95.5 billion from the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council

According to a paper published by the IMF, as of 2015 the supply of sukuk, fell "short of demand and, except in a few jurisdictions, issuance took place without a comprehensive strategy to develop the domestic market."

Takaful (Islamic insurance)

Main article: TakafulTakaful, sometimes called "Islamic insurance", differs from conventional insurance in that it is based on mutuality so that the risk is borne by all the insured rather than by the insurance company. Rather than paying premiums to a company, the insured contribute to a pooled fund overseen by a manager, and they receive any profits from the fund's investments. Any surplus in the common pool of accumulated premiums should be redistributed to the insured. (As with all Islamic finance, funds must not be invested in haram activities like interest-bearing instruments, enterprises involved in alcohol or pork.)

Like other Islamic finance operations, the takaful industry has been praised by some for providing "superior alternatives" to conventional equivalents and criticized by others for not being significantly different from them. Omar Fisher and Dawood Y. Taylor state that takaful has "reinvigorate human capital, emphasize personal dignity, community self-help, and economic self-development". On the other hand, according to Muhammad Akram Khan, Mahmud El-Gamal, the cooperative ideal has not been followed in practice by most takaful companies—who do not give their holders a voice in appointing and dismissing managers, or in setting "rates of premium, risk strategy, asset management and allocation of surpluses and profits". In a different critique, Mohammad Najatuallah Siddiqui argues that cooperation/mutuality does not change the essence of insurance—namely using the "law of large numbers" to protect customers.

As of the end of 2014 "gross takaful contributions" were estimated to be US$26 billion according to INCIEF (International Centre for Education in Islamic Finance). BusinessInsurance.com estimates the industry will reach $25 billion in size by the end of 2017.

Islamic credit cards

Sources dispute whether a truly shariah-compliant credit card has been developed. According to scholar Manzur Ahmad, despite their efforts, (at least as of 2008), Muslim scholars have not been able to find a legal basis in classical jurisprudence for an Islamic parallel of the credit card. Other scholars (Hossein Askari, Zamir Iqbal and Abbas Mirakhor) also agree that (at least as of 2009), attempts to devise "some sort of 'Islamic credit cards'" have found "no instrument that is compatible with shariah that can offer the same service as the conventional credit card". Among other complaints, critics note that credit cards encourage people to go into debt and to buy luxuries – both unIslamic activities.

Despite this, there are credit cards claiming to be shariah-compliant, generally following one of three arrangements, according to Lisa Rogak:

- A bank provides a line of credit to the cardholder and charges a monthly or yearly usage fee tied to the outstanding balance of the line of credit.

- A customer is allowed to buy an item with a card, but in the instant that the card goes through, the bank purchases the item before selling it to the cardholder at a higher price.

- A lease-purchase agreement where the bank holds title to the purchased item until the cardholder makes the final payment.

Another source (Beata Paxford writing in New Horizon) finds Islamic credit cards based not one of three but one of five structures:

- ujra (the client simply pays an annual service fee for using the card)

- ijara (card as a leased asset for which it pays installments on a regular basis)

- kafala (the bank acts as a kafil (guarantor) for the transactions of the card holder. For its services, the card holder is obligated to pay kafala bi ujra (fee)).

- qard ( the client acts as the borrower and the bank as a lender).

- bai al-ina/wadiah (The bank sells a product at a certain price which is the pool of means available for the client from its credit card. And then the bank repurchases the item from the client at a lower price. The difference between the prices is the income of the bank. In this model, the client would have a ceiling limit of money it could spend.)

According to yet another source, (Faleel Jamaldeen), Islamic "credit cards" are much like debit cards, with any transaction "directly debited" from the holder's bank account. According to Maryam Nasuha Binti Hasan Basri, et al., Islamic credit cards have played an important role in "the development and success of Islamic banking in Malaysia". Banks in that country offering Islamic credit cards as of sometime after 2012 include Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad, CIMB Islamic Bank Berhad, HSBC Amanah Malaysia Berhad, Maybank Islamic Berhad, RHB Islamic Bank Berhad, Standard Chartered Berhad, Am Islamic Bank Berhad.

Islamic funds

Islamic mutual funds—i.e. professionally managed investment funds that pools money from many investors to purchase securities that have been screened for sharia compliance—have been compared with "socially responsible" mutual funds—both seeking some combination of high returns/low risk like conventional funds, but also screening their holdings according to a non-profit seeking criteria. Islamic funds may also be unit trusts which are slightly different from mutual funds. The funds may hold equity and/or sukuk securities and/or own real estate.

Before a company's shares or other holdings can be purchased by a fund, the firm must be screened according to the sharia

- to filter out any company whose business involves industries or types of transactions that are prohibited by Islamic law (alcohol, tobacco, pork, adult entertainment industry, gambling, weapons, conventional banks and insurance companies) but also

- to make sure the company isn't "engaged in prohibited speculative transactions (involving uncertainty or gambling), which are likely leveraged with debt", the company's "financial ratios" must be examined to meet "certain financial benchmarks".

Islamic equity funds were launched in the early 1990s, and began growing fairly rapidly in about 2004. As of 2014 there were 943 Islamic mutual funds worldwide and as of May 2015, they held $53.2 billion of assets under management. Malaysia and Saudi Arabia dominate the sector with about 69% of total assets under management.

According to a 2015 study by Thomson Reuters, the market for Islamic funds has much room to grow as there is a "latent demand" for Islamic investment funds of $126 billion which "could rise to $185.1 billion by 2019". That survey of fund managers and investment firms found "an estimated 28 percent" of investors wanted to invest in sukuk-owning mutual funds, 21% in equity-owning funds and 15% in funds owning real estate.

Benchmarks to gauge the funds' performance have been established by Dow Jones and the FTSE Global Islamic Index Series. (Dow Jones established the first Islamic investment index. There are now "thousands" of Dow Jones Islamic indices varying by size, region, strategy, theme. These include fixed-income indices.)

At least in the earlier part of the 2000s, equity fund performance was not impressive. According to a study by Raphie Hayat and Roman Kraeuss of 145 Islamic equity funds from 2000 to 2009, the funds under-performed both Islamic and conventional equity benchmarks, particularly as the 2007–08 financial crisis set in. The study also found fund managers unsuccessful in their attempts to time the market. (An earlier study done by Said Elfakhani et al. before the 2007–08 financial crisis showed "no statistically significant difference" between Islamic and conventional funds in performance.)

A disadvantage Islamic funds have compared to conventional ones is that since they must "exclude companies with debt-to-market capitalization" above a certain ratio (which the industry has set at 33 percent), and since a fall in the price of the stock raises its debt-to-market capitalization ratio, falling stock prices may force a fund to sell stocks, "whether or not that was the best investment strategy". This puts the fund at risk of being forced into "buying high and selling low".

Sharia indices

- Credit Suisse HS50 Sharia Index

- Dow Jones Islamic Market Index

- Dubai Shariah Hedge Fund Index

- FTSE Sharia Global Equity Index

- Jakarta Islamic Index, Indonesia

- MSCI Barra Islamic Index

- S&P BSE 500 Shariah Index

Islamic derivatives

Main article: Sharia and securities tradingWhile "almost all conservative Sharia scholars" believe derivatives (i.e. securities whose price is dependent upon one or more underlying assets) are in violation of Islamic prohibitions on gharar, global standards for Islamic derivatives were set in 2010, with help of Bahrain-based International Islamic Financial Market and New York-based International Swaps and Derivatives Association. This Tahawwut/"Hedging Master Agreement" provides a structure under which institutions can trade derivatives such as profit-rate and currency swaps. Attempts to unify various swap documentation and has "strong parallels" to the 2002 ISDA Master and Schedule of the conventional banking industry. Tahawwut has not being widely used as of 2015, according to Harris Irfan, as the market is "awash" with "unique, bespoke ... contracts documenting the profit rate swap", all using "roughly the same structure", but differing in details and preventing the cost saving of standardization.

According to critic of Islamic finance El-Gamal, the Islamic finance industry has "synthesized" Islamic versions of "short and long sales as well as put and call options", (options are a "common form" of a derivative). The Islamic finance equivalent of a conventional call option (where the buyer has the right but not the obligation to buy in the future at a preset price, and so will make a profit if the price of the underlying asset rises above the preset price) are known as an urbun (down-payment) sale where the buyer has the right to cancel the sale by forfeiting her down-payment. The Islamic equivalent of the "premium" in a conventional call option is known as a "down-payment", and the equivalent of the "strike price" is called the "preset price". A put option (i.e. where the seller has the right but not the obligation to sell at a preset price by some point in the future, and so will profit if the price of the underlying asset falls) is called a 'reverse urbun` in Islamic finance.

Short-selling (though not technically a derivative) is also forbidden by conservative scholars because the investor is selling an item for which he never became the owner. However "some Shariah-compliant hedge funds have created an Islamic-short sale that is Shariah-certified". Some critics (like Feisal Khan and El-Gamal) complain it uses a work-around (requiring a "down-payment" towards the shorted stock) that is no different than "margin" regulations for short-selling used in at least one major country (the US), but entails "substantially higher fees" than conventional funds.

Wa'd

Wa'd (literally "promise"), is a principle that has come to underpin or to structure shariah-compliant hedging instruments or derivatives. Conventional hedging products such as forward currency contracts and currency swaps are prohibited in Islamic Finance. Wa'd has been called "controversial" or a mimicry of conventional products and "'Islamic' in form alone".

A "Double Wa'd" is a derivative that allows an investor to invest in and receive a return linked to some benchmark, sometimes ones that would normally be against shariah—such as an index of interest-bearing US corporate bonds. The investor's cash goes to a "special purpose entity" and they receive a certificate to execute the derivative. It involves a promise that on an agreed day in the future the investor will receive a return linked to whatever benchmark is chosen. Several features of the double wa'd (allegedly) make the derivative sharia-compliant:

- a special purpose entity where the investor's cash goes to avoid commingling,

- a shariah-compliant asset that is liquid and tradable—such as shares in a big company (like Microsoft) that has low levels of interest bearing debt (high levels being against shariah)—purchased with the investor's cash.

- a contract involving two mutually exclusive promises (hence "double"):

- that on an agreed day in the future the investor will receive a return linked to a given benchmark;

- that the bank will purchase the investor's asset "for a price equal to the benchmark"

So despite the fact that benchmark involves non-compliant investments, the contract is not "bilateral", because "the two undertaking promised are mutually exclusive", and this (proponents say) makes it in compliance with shariah.

In 2007, Yusuf DeLorenzo (chief sharia officer at Shariah Capital) issued a fatwa disapproving of the double wa'd in these situations (when the assets reflected in the benchmark were not halal), but this has not curtailed its use.

Put and call options

Like the Islamic equivalent for short sales, a number of Islamic finance institutions have been using the down-payment sale or urbun as an sharia-compliant alternative to the conventional call option. In this mode the Islamic equivalent of the option "premium" is known as a "down-payment", and the equivalent of the "strike price" is called the "preset price".

With a conventional call option the investor pays a premium for an "option" (the right but not the obligation) to buy shares of stock (bonds, currency, and other assets may also be shorted) in the hope that the stock's market price will rise above the strike price before the option expires. If it does, their profit is the difference between the two prices minus the premium. If it does not, their loss is the cost of the premium. When the Islamic investor uses an urbun they make a down-payment on shares or asset sale in hope the price will rise above the "preset price". If it does not their loss is the down-payment which they have the right to forfeit.

A put option (where the investor hopes to profit by selling rather than buying at a preset price) is called a 'reverse urbun` in Islamic finance.

- Criticism

The urbun and reverse urbun has been criticized by Sherif Ayoub, and according to El-Gamal and Feisal Khan, the procedure has many critics among scholars and analysts.

Microfinance

Microfinance seeks to help the poor and spur economic development by providing small loans to entrepreneurs too small and poor to interest non-microfinance banks. Its strategy meshes with the "guiding principles" or objectives of Islamic finance, and with the needs of Muslim-majority countries where a large fraction of the world's poor live, many of them small entrepreneurs in need of capital. (Many of them also among the estimated 72 percent of the Muslim population who do not use formal financial services, often either because they are not available, and/or because potential customer believe conventional lending products incompatible with Islamic law).

According to the Islamic Microfinance Network website (as of circa 2013), there are more than 300 Islamic microfinance institutions in 32 countries, The products used in Islamic microfinance may include some of those mentioned above—qard al hassan, musharaka, mudaraba, salam, etc.

Unfortunately, a number of studies have found Islamic microfinance reaching relatively few Muslims and lagging behind conventional microfinance in Muslim countries. Chiara Segrado writing in 2005 found "very few examples of actual MFIs operating in the field of Islamic finance and Islamic banks involved in microfinance". One 2012 report (by Humayon Dar and coauthors) found that Islamic microfinance made up less than one percent of the global microfinance outreach, "despite the fact that almost half of the clients of microfinance live in Muslim countries and the demand for Islamic microfinance is very strong."

An earlier 2008 study of 126 microfinance institutions in 14 Muslim countries found similarly weak outreach—only 380,000 members out of an estimated total population of 77 million there were "22 million active borrowers" of non-sharia-compliant microfinance institutions ("Grameen Bank, BRAC, and ASA") as of 2011 in Bangladesh, the largest sharia-compliant MFI or bank in that country had only 100,000 active borrowers.

(Muhammad Yunus, the founder of the Grameen Bank and microfinance banking, and other supporters of microfinance, though not part of the Islamic Banking movement, argue that the lack of collateral and lack of excessive interest in micro-lending is consistent with the Islamic prohibition of usury (riba).)

See also

- Muamalat

- Profit and loss sharing

- Sharia and securities trading

- Islamic banking and finance

- Murabaha

- Riba

- Shariah Board

- Dow Jones Islamic Fund

- Islamic marketing

References

Notes

- see also Hubar Hasan

- Winner of the 1997 IDB Prize in Islamic Banking

- Convert Umar Ibrahim Vadillo states: "For the last one hundred years the way of the Islamic reformers have led us to Islamic banks, Islamic Insurance, Islamic democracy, Islamic credit cards, Islamic secularism, etc. This path is dead. It has shown its face of hypocrisy and has led the Muslim world to a place of servile docility to the world of capitalism." According to critic Feisal Khan "there have thus been two broad categories of critic of the current version of IBF : the Islamic Modernist/Minimalist position, and the Islamic ultra Orthodox/Maximalist one. ... The ultra Orthodox ... agree with the Modernist/Minimalist criticism that contemporary Islamic banking is indeed nothing but disguised conventional banking but ... agitate for a truly Islamic banking and finance system".

- Faleel Jamaldeen divides Islamic finance instruments into four groups—designating bay al-muajil and salam "trade financing instruments" rather than asset-based instruments.

- for example bay al-muajil instruments are used in combination with murabaha, a ijara (leasing) may be used in combination with bai (purchasing) contract, and sukuk ("Islamic bonds") can be based on mudaraba, murabaha, salam, ijara, etc.

- according to Mehmet Asutay quotes Zubair Hasan

- "In order to pressurize the buyer to pay the installments promptly, the buyer may be asked to promise that in case of default, he will donate some specified amount for a charitable purpose."

- (Resolution 179 (19/5)).

- QardHasan lets you borrow from the community, interest-free, using the power of crowdfunding to get fair access to higher education.

- Deposit accounts held at a bank or other financial institution may be called transaction accounts, checking accounts, current accounts or demand deposit accounts. It is available to the account owner "on demand" and is available for frequent and immediate access by the account owner or to others as the account owner may direct. Transaction accounts are known by a variety of descriptions, including a current account (British English), chequing account or checking account when held by a bank, share draft account when held by a credit union in North America. In the UK, Hong Kong, India and a number of other countries, they are commonly called current or cheque accounts.

- "...the Holy Qur’an has expressly said, 'And if he (the debtor) is short of funds, then he must be given respite until he is well off.'" (2:280)

- According to Mahmud El-Gamal Classical jurists "recognized two types of property possession based on liability risk": trust and guaranty. 1) With a trust (which result, e.g., from deposits, leases, and partnerships), the possessor only responsible for compensating the owner for damage to property if the trustee has been negligence or committed a transgression. 2) With guaranty the possessor guarantees the property against any damage, whether or not the guarantor was negligent or committed a transgression. Classical jurists consider the two possessions mutually exclusive, so if two different "considerations" conflict—one stating the property is held in trust and another stating in guaranty—"the possession of guaranty is deemed stronger and dominant, and rules of guaranty are thus applied".

- According to data published by the Islamic Financial Services Board.

- A unit trust differs from a mutual fund in that it operates under a trust system where investors' assets are entrusted to trustee. A mutual fund is like a limited liability company where investors are like shareholders in a company.

- Although not entirely in agreement with Sheikh Yusuf, the shariah board head (Sheikh Hussain Hamed Hassan) at the firm where the swap was developed, (Deutsche Bank) "took pains to ensure that he involved in both the development and distribution phases of each new product ... But it was impossible to beat the bankers. Across the industry, other firms picked up on the methodology and began issuing their own products many of whom were not as intimately familiar with the structure. Corners were cut and products of dubious provenance continued to pour out from the sales desks of less scrupulous institutions."

- options are a "common form" of a derivative.

- "Half of global poverty reside in Muslim world ..."

- This number excludes 80,000 cooperative members in Indonesia and all in Iran.

Citations

- "Shariah Law Guide". Trustnet.com.

- Khan, Ajaz A., Sharia Compliant Finance Archived 11 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine| halalmonk.com

- "Islamic Banking & Finance | Noorbank". www.noorbank.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- Farooq, Riba-Interest Equation and Islam, 2005: pp. 3–6

- Khan, What Is Wrong with Islamic Economics?, 2013: pp. 216–226

- "Islamic finance: Big interest, no interest". The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. 13 September 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- Mohammed, Naveed (27 December 2014). "The Size of the Islamic Finance Market". Islamic Finance.

- Towe, Christopher; Kammer, Alfred; Norat, Mohamed; Piñón, Marco; Prasad, Ananthakrishnan; Zeidane, Zeine (April 2015). Islamic Finance: Opportunities, Challenges, and Policy Options. IMF. p. 11. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- Khan, What Is Wrong with Islamic Economics?, 2013: pp. xv–xvi

- The Islamic Banking and Finance Database provides more information on the subject. "World Database for Islamic Banking and Finance". Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ El-Hawary, Dahlia; Grais, Wafik; Iqbal., Zamir (2004). Regulating Islamic financial institutions: The nature of the regulated. World Bank policy research working paper 3227. Washington, DC: World Bank. p. 5. SSRN 610268.

- Visser, Hans, ed. (January 2009). "4.4 Islamic Contract Law". Islamic Finance: Principles and Practice. Edward Elgar. p. 77. ISBN 9781848449473. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

The prevalent position, however, seems to be that creditors may impose penalties for late payments, which have to be donated, whether by the creditor or directly by the client, to a charity, but a flat fee to be paid to the creditor as a recompense for the cost of collection is also acceptable to many fuqaha.

- Kettell, Brian (2011). The Islamic Banking and Finance Workbook: Step-by-Step Exercises to help you ... Wiley. p. 38. ISBN 9781119990628. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

The bank can only impose penalties for late payment by agreeing to 'purify' them by donating them to charity.

- "FAQs and Ask a Question. Is it permissible for an Islamic bank to impose penalty for late payment?". al-Yusr. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- Hussain, Mumtaz; Shahmoradi, Asghar; Turk, Rima (June 2015). IMF Working paper, An Overview of Islamic Finance (PDF). p. 8. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ F., J. (8 October 2014). "Why Islamic financial products are catching on outside the Muslim world". The Economist. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- Mervyn K. Lewis, Latifa M. Algaoud: Islamic Banking, Cheltenham, 2001

- ^ Khan, Islamic Banking in Pakistan, 2015: p. 89

- Fasman, Jon (20 March 2015). "[Book Review] Heaven's Bankers by Harris Irfan". The New York Times. New York Times. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ Usmani, Introduction to Islamic Finance, 1998: p. 12

- Khan, What Is Wrong with Islamic Economics?, 2013: p. 275

- Khan, Islamic Banking in Pakistan, 2015: p. 86

- Iqbal, Munawar (1998). Challenges facing Islamic banking (PDF). Islamic Development Bank. pp. 15–16.

- Hasan, Zubair (21 August 2014). Risk-sharing versus risk-transfer in Islamic finance: An evaluation (PDF). Kuala Lumpur: The Global University of Islamic Finance (INCEIF). MPRA Paper No. 58059, (Munich Personal RePEc Archive). Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- Lewis, M. K. and Algaoud, L. M. (2001) Islamic banking. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Nathan, S. and Ribiere, V. (2007) From knowledge to wisdom: The case of corporate governance in Islamic banking. The Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 37 (4), pp. 471–483.

- Dar, Humayon A. 2010. Islamic banking in Iran and Sudan. Business Asia, 27 June 2010

- ^ El-Gamal, Islamic Finance, 2006: p. 21

- Ariff, Mohamed (September 1988). "Islamic Banking". Asian-Pacific Economic Literature. 2 (2): 48–64. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8411.1988.tb00200.x.

- "What is Islamic Banking?". Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance. Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- Warsame, Mohamed Hersi (2009). "4. PRACTICE OF INTEREST FREE FINANCE AND ITS SIGNIFICANCE" (PDF). The role of Islamic finance in tackling financial exclusion in the UK. Durham University. p. 183. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ Usmani, Introduction to Islamic Finance, 1998: p. 11

- Kamel, Saleh (1998). Development of Islamic banking activity: Problems and prospects (PDF). Jeddah: Islamic Research and Training Institute, Islamic development Bank. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- Irfan, Heaven's Bankers, 2015: p. 53

- Irfan, Heaven's Bankers, 2015: p. 236

- "Islamic mortgages: Shari'ah-based or Shari'ah-compliant?". New Horizon Magazine. 13 March 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- Ali, Engku Rabiah Adawiah Engku. "SHARIAH-COMPLIANT TO SHARIAH-BASED FINANCIAL INNOVATION: A QUESTION OF SEMANTICS OR PROGRESSIVE MARKET DIFFERENTIATION" (PDF). 4th SC-OCIS Roundtable, 9–10 March 2013, Ditchley Park, Oxford, UK. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- Irfan, Heaven's Bankers, 2015: p. 198

- Irfan, Heaven's Bankers, 2015: p. 192

- 'Islamic finance: What does it change, what it does not? Structure-objective mismatch and its consequences. International Centre for Education in Islamic Finance (INCEIF). 21 February 2010.

- ^ Khan, Islamic Banking in Pakistan, 2015: p. 112

- Vadillo, Umar Ibrahim (19 October 2013). "Questionnaire for Jurisconsults, subject specialists and general public in connection with re-examination of Riba/Interest based laws by Federal Shariah Court". Gold Dinar and Muamalat. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Khan, Islamic Banking in Pakistan, 2015: p. 114

- ^ Towe, Christopher; Kammer, Alfred; Norat, Mohamed; Piñón, Marco; Prasad, Ananthakrishnan; Zeidane, Zeine (April 2015). Islamic Finance: Opportunities, Challenges, and Policy Options. IMF. p. 9. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- Hussain, M., A. Shahmoradi, and R. Turk. 2014. "Overview of Islamic Finance," IMF Working Paper (forthcoming), International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

- ^ Khan, What Is Wrong with Islamic Economics?, 2013: pp. 329–330

- ^ "Islamic Banking. Profit-and-Loss Sharing". Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance. 15 August 2015. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- Jamaldeen, Islamic Finance For Dummies, 2012: pp. 160–62

- Jamaldeen, Islamic Finance For Dummies, 2012: p. 96

- ^ Khan, Islamic Banking in Pakistan, 2015: p. 90

- Rizvi, Syed Aun R.; Bacha, Obiyathulla I.; Mirakhor, Abbas (1 November 2016). Public Finance and Islamic Capital Markets: Theory and Application. Springer. p. 85. ISBN 9781137553423. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Khan, What Is Wrong with Islamic Economics?, 2013: pp. 322–23

- ^ "islamic finance for dummies cheat sheet". Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- Khan, Islamic Banking in Pakistan, 2015: p. 87

- Jamaldeen, Islamic Finance For Dummies, 2012: p. 153

- ^ Curtis (3 July 2012). "Islamic Banking: A Brief Introduction". Oman Law Blog. Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle LLP. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ "Current account deposits". financialislam.com. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- Khan, What Is Wrong with Islamic Economics?, 2013: p. 330

- "Concept and ideology :: Issues and problems of Islamic banking". Islami Bank Bangladesh Limited. Archived from the original on 16 July 2007. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB). 2014. Islamic Financial Services Industry Stability Report. Kuala Lumpur: IFSB.

- Jamaldeen, Islamic Finance For Dummies, 2012: p. 89

- ^ Jamaldeen, Islamic Finance For Dummies, 2012: p.160

- ^ Jamaldeen, Islamic Finance For Dummies, 2012: p. 158

- Jamaldeen, Islamic Finance For Dummies, 2012: pp. 218–26

- Yousef, Tarik M. (2004). "The Murabaha Syndrome in Islamic Finance: Laws, Institutions, and Politics" (PDF). In Henry, Clement M.; Wilson, Rodney (eds.). THE POLITICS OF ISLAMIC FINANCE. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Iqbal, Munawar, and Philip Molyneux. 2005. Thirty years of Islamic banking: History, performance and prospects. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kuran, Timur. 2004. Islam and Mammon: The economic predicaments of Islamism. Princeton, NJ; Princeton University Press

- Lewis, M. K. and L. M. al-Gaud 2001. Islamic banking. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, US: Edward Elgar

- Yousef, T. M. 2004. The murabaha syndrome in Islamic finance: Laws, institutions and policies. In Politics of Islamic finance, ed. C. M. Henry and Rodney Wilson. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

- Dusuki, A W; Abozaid, A (2007). "A Critical Appraisal on the Challenges of Realizing Maqasid al-Shariah". International Journal of Economic, Management & Accounting. 19, Supplementary Issues: 146, 147.

- THE DECLINING BALANCE CO-OWNERSHIP PROGRAM. AN OVERVIEW| Guidance Residential, LLC | 2012

- "Islamic banks commercial transactions". Financial Islam - Islamic Finance. Archived from the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- Zubair Hasan, "Fifty years of Malaysian economic development: Policies and achievements", Review of Islamic Economics, 11 (2) (2007)

- Asutay, Mehmet. 2007. Conceptualization of the second best solution in overcoming the social failure of Islamic banking and finance: Examining the overpowering of the homoislamicus by homoeconomicus. IIUM Journal of Economics and Management 15 (2) 173

- Moriguchi, Takao; Khattak, Mudeer Ahmed (2016). "Contemporary Practices of Musharakah in Financial Transactions". IJMAR International Journal of Management and Applied Research. 3 (2). Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- Nomani, Farhad; Rahnema, Ali. (1994). Islamic Economic Systems. New Jersey: Zed books limited. pp. 99–101. ISBN 1-85649-058-0.

- "Is Musharakah Mutanaqisah a practical alternative to conventional home financing?". Islamic Finance News. 2 December 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- Kettell, Brian (2011). The Islamic Banking and Finance Workbook: Step-by-Step Exercises to Help You ... John Wiley & Sons. p. 25. ISBN 9780470978054. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- Meera, Ahamed Kameel Mydin; Razak, Dzuljastri Abdul. Islamic Home Financing through Musharakah Mutanaqisah and al-Bay' Bithaman Ajil Contracts: A Comparative Analysis. Department of Business Administration. Kulliyyah of Economics and Management Sciences International Islamic University Malaysia. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- Khan, Islamic Banking in Pakistan, 2015: p. 103

- "Modes of financing". Financial Islam - Islamic Finance. Archived from the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Turk, Main Types and Risks, 2014: p. 31

- Irfan, Harris (2015). Heaven's Bankers. Overlook Press. p. 135.

- ^ Usmani, Introduction to Islamic Finance, 1998: p. 65

- ^ Islamic Finance: Instruments and Markets. Bloomsbury Publishing. 2010. p. 131. ISBN 9781849300391. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- Irfan, Harris (2015). Heaven's Bankers. Overlook Press. p. 139.

- ^ Haltom, Renee (Second Quarter 2014). "Econ Focus. Islamic Banking, American Regulation". Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- Usmani, Introduction to Islamic Finance, 1998: p. 71

- "Misused murabaha hurts industry". Arabian Business. 1 February 2008.

- "TRADE-BASED FINANCING MURABAHA (COST-PLUS SALE)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "Bai Muajjal". IFN, Islamic Finance News. 27 November 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ Visser, Islamic Finance, 2013: p. 66

- Hasan, Zubair (2011). Scarcity, self-interest and maximization from Islamic angle. p. 318. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- "INVESTMENT MODES: MUDARABA, MUDHARAKA, BAI-SALAM AND ISTISNA'A". Banking Articles. February 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2016.