| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. The specific problem is: Too much content (in 'By country') on recent COVID-19 pandemic instead of curfews as a whole throughout history. Please help improve this article if you can. (November 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

A curfew is an order that imposes certain regulations during specified hours. Typically, curfews order all people affected by them to remain indoors during the evening and nighttime hours. Such an order is most often issued by public authorities, but may also be given by the owner of a house to those living in the household. For instance, children are often given curfews by their parents, and an au pair is traditionally given a curfew by which time he or she must return to his or her host family's home. Some jurisdictions have juvenile curfews which affect all persons under a certain age not accompanied by an adult or engaged in certain approved activities.

Curfews have been used as a control measure in martial law, as well as for public safety in the event of a disaster, epidemic, or crisis. Various countries have implemented such measures throughout history, including during World War II and the Gulf War. The enforcement of curfews has been found to disproportionately affect marginalised groups, including those who are homeless or have limited access to transportation.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, curfews were implemented in several countries, including France, Italy, Poland and Australia, as a measure to limit the spread of the virus. However, recent studies have reported negligible or no effect, and even a potential increase in virus transmission. The use and enforcement of curfews during the pandemic has been associated with human rights violations and mental health deterioration, further complicating their use as a control measure. Curfews may also impact road safety, as studies indicate a potential decrease in crashes during curfew hours but an increase in crashes before curfew due to rushing.

Etymology

Arsenio Frugoni, Quoted in Urban Space in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern AgeBetween the evening twilight and the grayness before dawn one can hardly make out the walls of the houses, for there is no lighting in the medieval city as we said. At evening curfew the women cover the coals in the hearth with ash to reduce the fire hazard. The houses are built with beams of oak and every one is a potential tinderbox waiting to blaze up, so at night the only flames left burning are the candles before the holy images. Why would the streets need to be lit anyway? In the evening the entrances to the dangerous neighborhoods are barred, chains are stretched across the river to prevent a surprise attack from barbarian raiders coming upstream, and the city gates are locked tight. The city is like one big household, with everything well secured.

The word "curfew" /ˈkɜːr.fjuː/ comes from the Old French phrase "couvre-feu", which means "cover fire". It was later adopted into Middle English as "curfeu", which later became the modern "curfew". Its original meaning refers to a law by William the Conqueror that all lights and fires should be covered to extinction at the ringing of an eight o'clock bell to prevent the spread of destructive fire within communities in timber buildings. With the same derivation a "curfew" also refers to a device used to cover the embers of a fire at night, allowing it to be re-ignited more easily in the morning.

Historical

Further information: Curfew bell § HistoryCurfews have been used since the Middle Ages to limit uprisings among subordinate groups, including Anglo-Saxons under William the Conqueror. Prior to the U.S. Civil War, most Southern states placed a curfew on slaves.

Modern curfews primarily focus on youth as well as during periods of war and other crisis. In the United States, progressive reformers pushed for curfews on youth, successfully securing bans on children's nighttime presence on streets in cities such as Louisville, Kentucky and Lincoln, Nebraska. General curfews were also put into place after crises such as the 1871 Chicago Fire.

Wartime curfews were also implemented during the First and Second World Wars. A formal curfew introduced by the British board of trade ordered shops and entertainment establishments to extinguish their lights by 10:30 p.m. to save fuel during World War I.

Types

- An order issued by public authorities or military forces requiring everyone or certain people to be indoors at certain times, often at night. It can be imposed to maintain public order (as was the case with the northeast blackout of 2003, the 2005 French riots, the 2010 Chile earthquake, the 2011 Egyptian revolution, and the 2014 Ferguson unrest), or suppress targeted groups. Curfews have long been directed at certain groups in many cities or states, such as Japanese-American university students on the West Coast of the United States during World War II, African-Americans in many towns during the time of Jim Crow laws, or people younger than a certain age (usually within a few years either side of 18) in many towns of the United States since the 1980s. In recent times, curfews have been imposed by many countries during disease epidemics or pandemics such as the COVID-19 pandemic; see below.

- A rule set for a child or teenager by their parents or legal guardians, requiring them to return home by a specific time, usually in the evening or night. This may apply daily, or vary with the day of the week, e.g., if the minor has to go to school the next day.

- An order by the head of household to a domestic assistant such as an au pair or nanny. The domestic assistant must then return home by a specific time.

- A daily requirement for guests to return to their hostel before a specified time, usually in the evening or night.

- A daily requirement that a person subject to a court order, such as probation or bail conditions, must return to their home before a certain hour and be inside it until a certain hour of the morning.

- In baseball, a time after which a game must end, or play be suspended. For example, in the American League the curfew rule for many years decreed that no inning could begin after 1 am local time (with the exception of international games).

- In aeronautics, night flying restrictions may restrict aircraft operations over a defined period in the nighttime, to limit the disruption of aircraft noise on the sleep of nearby residents. Notable examples are the London airports of Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted, which operate under the Quota Count system.

- In a few locations in the UK, patrons of licensed premises may not enter after a "curfew" time, also known as "last orders". In Inverclyde, for example, this is currently set at 12:00 am.

- In many boarding schools, students are usually ordered by school staff to stay in their dormitories at night.

By country

Australia

On 17 August 2011, a nighttime curfew was imposed on children who had run amok in the streets of Victoria after repeating youth offenses.

On 2 August 2020, following the surge of COVID-19 cases in Victoria, especially in Melbourne, Victorian premier Daniel Andrews declared a state of disaster across the state and imposed stage 4 lockdown in Metropolitan Melbourne. The new measures included nighttime curfew, which was implemented across Melbourne from 20:00 to 05:00 (AEST). The restrictions came into effect at 18:00 (6 pm) and lasted until 28 September 2020 (5 am).

On 16 August 2021, following a surge of COVID-19 cases and a drop in compliance in restrictions in Victoria, especially in Melbourne, Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews reinstated the curfew in Melbourne, this time from 21:00 to 05:00 (AEST) effective midnight 17 August 2021 until at least 2 September 2021.

On 20 August 2021, as COVID-19 cases continued to surge in New South Wales, NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian imposed a curfew in the local government areas of Bayside, Blacktown, Burwood, Campbelltown, Canterbury-Bankstown, Cumberland, Fairfield, Georges River, Liverpool, Parramatta, Strathfield, and parts of Penrith, from 9:00 pm to 5:00 am (AEST) beginning from 23 August.

Belgium

Main article: COVID-19 pandemic in BelgiumOn 17 October 2020, due to surge of COVID-19 cases and deaths in Belgium, Prime Minister Alexander De Croo announced a nationwide curfew from midnight to 05:00 am local time. The curfew was imposed on 19 October 2020 and was to last for four weeks. The government also announced the closure of cafes, bars and restaurants for one month and alcohol sales were banned after 8:00 pm local time.

Bangladesh

Main articles: 2024 Bangladesh quota reform movement and Non-cooperation movement (2024)On 19 July 2024 Bangladesh government declared a national curfew and announced plans to deploy the army to tackle the country’s worst unrest in a decade. The government announced the imposition of a curfew after days of clashes at protests against government job quotas across the country.

On 4th August 2024 Bangladesh government declared a curfew again following the deadliest day of the protest with Mass shooting and a violent crackdown on the Non Cooperation Movement.

Canada

See also: COVID-19 pandemic in Canada

On 6 January 2021, due to a surge of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the province of Quebec, a curfew was ordered by the premier of Quebec François Legault. The curfew was adjusted for different areas of the province depending on the number of cases, amongst other criteria. The more populous areas, such as the urban areas of Montréal and Quebec City qualified as "red zones" and were placed under a curfew from 8 pm to 5 am while the less urban areas were either "orange zones" with a curfew from 9:30 pm to 5 am. This curfew was expected to be in effect from 9 January up to and including 8 February 2021. "Yellow zones" did not have curfew. However, the curfew did not end in February. It ended on May 28, 2021. On December 30, 2021, Quebec reinstated the nightly curfew this time starting at 10:00 pm to 5:00 am. Following the reinstatement of the curfew, studies came out doubting its effectiveness in lowering the transmission of COVID-19.

Egypt

On 28 January 2011, during the Egyptian Revolution and following the collapse of the police system, President Hosni Mubarak declared a country-wide military enforced curfew. However, it was ignored by demonstrators who continued their sit-in in Tahrir Square. Concerned residents formed neighborhood vigilante groups to defend their communities against looters and the newly escaped prisoners.

On the second anniversary of the revolution, in January 2013, a wave of demonstrations swept the country against President Mohamed Morsi who declared a curfew in Port Said, Ismaïlia, and Suez, three cities where deadly street clashes had occurred. In defiance, the locals took to the streets during the curfew, organizing football tournaments and street festivals, prohibiting police and military forces from enforcing the curfew.

Fiji

See also: COVID-19 pandemic in FijiOn 27 March 2020, Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama announced a nationwide curfew from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m. that would take effect on 30 March. The times have been adjusted forward and backward on several occasions, but as of January 2022, this curfew is still in effect. The government of Fiji maintains that this curfew will stay in effect for the foreseeable future.

France

See also: COVID-19 pandemic in FranceOn 14 October 2020, following the surge of COVID-19 cases and deaths in France that threatened to overwhelm hospitals, French President Emmanuel Macron declared a national state of public health emergency for the second time and imposed a nighttime curfew in the Île-de-France region that includes Paris, as well as Grenoble, Lille, Lyon, Marseille, Montpellier, Rouen, Saint-Etienne, and Toulouse. The curfew ran from 09:00 pm to 06:00 am local time (CEST) (08:00 pm to 05:00 am CET) and was implemented from 17 October 2020 to last four weeks.

Under the rules, people in those cities could only leave their homes for essential reasons, and anyone who violated the curfew would face a fine of 135 euros ($158.64) for the first offence. A second offence would bring a far steeper fine of 1,500 euros, or around $1,762. On 23 October, the curfew was expanded to 38 departments and French Polynesia. In total, 54 departments and one overseas collectivity were affected by new restrictions, comprising 46 million people, or two-thirds of the French population.

Iceland

Under Iceland's Child Protection Act (no. 80/2002 Art. 92), minors aged 12 and under may not be outdoors after 20:00 (8:00 pm) unless accompanied by an adult. Minors aged 13 to 16 may not be outdoors after 22:00 (10:00 pm), unless on their way home from a recognized event organized by a school, sports organization or youth club. During the period 1 May to 1 September, children may be outdoors for two hours longer.

Children and teenagers that break curfew are taken to the local police station and police officers tell their parents to come and get them. The age limits are based upon year of birth, not date of birth. If a parent cannot be reached, the child or teenager is taken to a shelter.

Ireland

Several medieval towns in Ireland had a curfew after the English model. In Galway a curfew bell was rung every night before the town gates were locked. In Kilkenny the night watchmen stood guard over the market stalls "from curfew to cockcrow."

During the 1916 Easter Rising, Dublin was under curfew between 7:30 p.m. and 5:30 am.

During the Irish War of Independence curfews were regularly imposed, including in 1920 in Dublin between midnight and 5 am. Curfew between 9 p.m. and 3 a.m. was imposed on Cork City in July 1920 after the shooting of Gerald Smyth; in August it was extended to many parts of Munster.

In 1921 Limerick was under a curfew. In 1921, Dublin's curfew began at 10 pm, moved to 9 p.m on 4 March.

In the Republic of Ireland, a restriction on movement order may be placed on an offender, which may include a curfew element.

Italy

See also: COVID-19 pandemic in ItalyIn Italy a curfew went into effect from October 2020 to limit the spread of COVID-19. Between 22 and 26 October 2020 Lombardy, Campania, Lazio, Sicily, Calabria and Piedmont imposed a curfew between 11.00 pm and 5.00 am, so any movement was prohibited.

With the ministerial decree of 3 November 2020, corrected with the DPCM of 3 December 2020, and 14 January 2021, the Italian Regions are grouped into three types of different epidemiological scenarios. A curfew is instituted nationwide from 10 pm to 5 am, shopping centers are ordered to close on weekends, and the use of distance learning for high schools.

There have been many protests and riots against the curfew nationwide since it came into effect. However, the curfew has not been lifted by the government.

Jersey

During the German occupation of the Channel Islands, curfews were imposed.

Morocco

See also: COVID-19 pandemic in MoroccoOn 21 December 2020, the government of Morocco first announced a nationwide nighttime curfew as part of its response to the COVID-19 pandemic, to come into effect on 23 December. Initially implemented for a three-week period from 9:00 pm–6:00 am, it was extended throughout 2021 alongside the state of health emergency, with hours altered during Ramadan (8:00 pm–6:00 am), and from May to early August (11:00 pm–4:30 am). The curfew was lifted on 10 November 2021.

Netherlands

See also: COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands and 2021 Dutch curfew riots

In the Netherlands, a curfew from 9:00 pm to 4:30 am local time went into effect on 23 January 2021 to limit the spread of COVID-19. Across the first two nights, 5,765 people were given the 95 euro fine for disobeying the curfew. Nationwide anti-curfew riots occurred from 23 until 26 January, resulting in the arrests of over 575 people. On 8 February, the government announced an extension of the curfew until 2 March. The curfew was lifted on April 28, 2021 and has not been reinstated since then.

Philippines

In 1565, the Spanish conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi arrived in Cebu to colonize the islands that would later be known as the Philippines. Legazpi constructed a fort and instituted a curfew for those entering it at night, citing concerns that "women prostituted themselves in the camp." During the American colonial period in the Philippines at the turn of the 19th century, Manila was under a "Curfew Order" requiring them not to go out of their houses after 7:00 pm, and later the restriction changed to 8:30 pm, then to 10:00 pm, then to 11:00 pm, and finally revoked in 1901.

On September 22, 1972, the day after then President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law, he issued General Order No. 4, mandating a curfew from midnight to 4:00 a.m., and anyone who violated this curfew would be arrested and taken into custody. In December 1972, Marcos conditionally lifted the curfew, and in 1977, he announced the complete removal of the curfew as part of efforts to ease restrictions imposed during martial law. The primary goal of the curfew was to reduce crime, among other reasons.

On May 23, 2017, then President Rodrigo Duterte proclaimed martial law in the entire Mindanao island group as a response to the siege of Marawi, and the proclamation involved curfews. 129 areas in Mindanao had curfews in 2017. After winning the 2016 presidential elections and before starting his term, Duterte proposed a nationwide curfew for minors.

There have been local ordinances regarding curfew for minors in some cities and municipalities but no nationwide law. Article 129 of the Presidential Decree 603 in 1974 permits c]ty or municipal councils to implement "curfew hours for children as may be warranted by local conditions." In 2022, a proposed bill was introduced in the House of Representatives to implement a nationwide curfew. However, the bill has been pending with the Committee on the Welfare of Children since July 2022.

The curfew for minors in the Philippines is a debatable topic. Those in favor argue that curfews will promote the children's safety and welfare, while those against state that curfews infringe on children's right to travel in their vicinity and their parents' right to nurture them. In 2017, the Supreme Court of the Philippines ruled on the constitutionality of some of these local ordinances after a group filed a case. The high court upheld the curfew for minors in Quezon City but did not support the curfews implemented in Manila and Navotas.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, several areas of the Philippines enforced curfews, including Metro Manila, Bulacan, Cavite, Laguna, Rizal, Cebu, and Cagayan de Oro.

Poland

See also: Militsiya hourA strict nationwide curfew was imposed in December 1981 following the introduction of Martial law in Poland.

Slovenia

See also: COVID-19 pandemic in SloveniaIn Slovenia, a curfew was implemented in February 1942 in the area occupied by Italy during World War II. More recently, it was imposed in October 2020 during the COVID-19 epidemic to limit the spread of the virus. The curfew, which was referred to as the "epidemiological curfew," was enforced from 20 October 2020 to 12 April 2021, from 9:00 pm to 6:00 am local time, for a total of 174 days. The measure was recommended by the government's COVID-19 expert group and enforced under the Infectious Diseases Act. The curfew was criticized by some experts as unnecessary and was challenged for its potential violation of human rights. In April 2023, the Constitutional Court declined to assess the curfew regulations as no longer valid, although a concern has been raised that similar measures may be implemented in the future.

South Korea

In South Korea, a curfew was imposed following the American military occupation and end of Japanese colonial rule in 1945. It remained in place throughout the Korean War and decades thereafter until it was lifted on 4 January 1982 under the presidency of Chun Doo-hwan, a few months after the capital Seoul was awarded host of the 1988 Summer Olympics.

Spain

See also: COVID-19 pandemic in SpainIn Spain, a curfew was imposed from 11:00 pm to 6:00 am local time on 25 October 2020 to limit the spread of COVID-19, in addition to some Autonomous Communities starting the curfew at 10:00 pm.

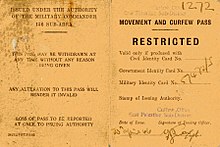

Sri Lanka

In Sri Lanka, the Sri Lanka Police are empowered to declare and enforce a Police Curfew in any police area for any particular period to maintain the peace, law and order under the Police Ordinance. Under the emergency regulations of the Public Security Ordinance, the President may declare a curfew over the whole or over any part of the country. Travel is restricted, during a curfew, to authorised persons such as police, armed forces personal and public officers. Civilians may gain a Curfew Pass from a police station to travel during a curfew.

Ukraine

During the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, curfews are imposed in all oblasts of Ukraine except Zakarpattia, usually lasting from 12 am to 5 am, although may differ depending on specific oblast.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom's 2003 Anti-Social Behaviour Act created zones that allow police from 9 pm to 6 am to hold and escort home unaccompanied minors under the age of 16, whether badly behaved or not. Although hailed as a success, the High Court ruled in one particular case that the law did not give the police a power of arrest, and officers could not force someone to come with them. On appeal the court of appeal held that the act gave police powers to escort minors home only if they are involved in, or at risk from, actual or imminently anticipated bad behaviour.

In a few towns in the United Kingdom, the curfew bell is still rung as a continuation of the medieval tradition where the bell used to be rung from the parish church to guide travelers safely towards a town or village as darkness fell, or when bad weather made it difficult to follow trackways and for the villagers to extinguish their lights and fires as a safety measure to combat accidental fires. Until 1100 it was against the law to burn any lights after the ringing of the curfew bell. In Morpeth, the curfew is rung each night at 8 pm from Morpeth Clock Tower. In Chertsey, it is rung at 8 pm, from Michaelmas to Lady Day. A short story concerning the Chertsey curfew, set in 1471, and entitled "Blanche Heriot. A legend of old Chertsey Church" was published by Albert Richard Smith in 1843, and formed a basis for the poem "Curfew Must Not Ring Tonight". At Castleton in the Peak District, the curfew is rung from Michaelmas to Shrove Tuesday. At Wallingford in Oxfordshire, the curfew bell continues to be rung at 9 pm rather than 8 pm which is a one-hour extension granted by William the Conqueror as the Lord of the town was a Norman sympathiser. However, none of these curfew bells serves its original function.

Northern Ireland

During the Troubles in Northern Ireland, the British Army made an attempt to search for illegal items secretly held by Official IRA (OIRA) and the Provisional IRA (IRA) in Falls Road, Belfast, a predominantly Catholic neighbourhood. The operation, which became known as the Falls Curfew, took place from 3 to 5 July 1970, with British troops carrying out searches. As it ended, local youths attacked the soldiers, who responded by deploying riot control tactics; the confrontation quickly developed into a series of gunfights between the British Army and the IRA. After four hours, the Army sealed off the area and imposed a 36-hour curfew, carrying out more searches and recovering 96 weapons before the operation ended. Ultimately, 4 civilians were killed, 78 wounded and 337 arrested. 18 soldiers were also wounded. The curfew was later found to be illegal and no further attempts to impose curfews were made during the Troubles.

During the 2020–21 coronavirus pandemic, a curfew was imposed between Christmas 2020 and New Years 2021, 8 p.m. to 6 am, to reduce contagion.

United States

Curfew law in the United States is usually a matter of local ordinance (mainly applied by a municipality or county), rather than federal law. However, the Constitution guarantees certain rights, which have been applied to the states through the 14th Amendment. Hence, any curfew law may be overruled and struck down if, for example, it violates 1st, 4th, 5th or 14th Amendment rights.

Nonetheless, curfews are set by state and local governments. They vary by state and even by county or municipality.

American military curfews are a tool used by commanders at various installations to shape the behavior of soldiers.

Juvenile curfews

Local ordinances and state statutes may make it unlawful for minors below a certain age to be on public streets, unless they are accompanied by a parent or an adult or on lawful and necessary business on behalf of their parents or guardians. For example, a Michigan state law provides that "o minor under the age of 12 years shall loiter, idle or congregate in or on any public street, highway, alley or park between the hours of 10 o'clock p.m. and 6 o'clock a.m., unless the minor is accompanied by a parent or guardian, or some adult delegated by the parent or guardian to accompany the child." MCLA § 722.751; MSA § 28.342(1). Curfew laws in other states and cities typically set forth different curfews for minors of different ages.

The stated purpose of such laws is generally to deter disorderly behavior and crime, while others can include to protect youth from victimization and to strengthen parental responsibility, but their effectiveness is subject to debate. Generally, curfews attempt to address vandalism, shootings, and property crimes, which are believed to happen mostly at night, but are less commonly used to address underage drinking, drunk driving, risky driving, and teenage pregnancy. Parents can be fined, charged or ordered to take parenting classes for willingly, or through insufficient control or supervision, permitting the child to violate the curfew. Many local curfew laws were enacted in the 1950s and 1960s to attack the "juvenile delinquent" problem of youth gangs. Most curfew exceptions include:

- accompanied by a parent or an adult appointed by the parent;

- going to or coming home from work, school, religious, or recreational activity;

- engaging in a lawful employment activity or;

- involved in an emergency;

Some cities make it illegal for a business owner, operator, or any employee to knowingly allow a minor to remain in the establishment during curfew hours. A business owner, operator, or any employee may be also subject to fines.

A 2011 UC-Berkeley study looked at the 54 larger U.S. cities that enacted youth curfews between 1985 and 2002 and found that arrests of youths affected by curfew restrictions dropped almost 15% in the first year and approximately 10% in following years. However, not all studies agree with the conclusion that youth curfew laws actually reduce crime, and many studies find no benefit or sometimes even the opposite. For example, one 2016 systematic review of 12 studies on the matter found that the effect on crime is close to zero, and can perhaps even backfire somewhat.

There are also concerns about racial profiling. In response to concerns about racial profiling, Montgomery County, Maryland, passed a limited curfew, which would permit police officers to arrest juveniles in situations that appear threatening.

Mall curfews

Main article: Mall curfewMany malls in the United States have policies that prohibit minors under a specified age from entering the mall after specified times, unless they are accompanied by a parent or another adult or are working at the mall during curfew times. Such policies are known as mall curfews. For example, the Mall of America's Youth Supervision Policy, requires all minors visiting Mall after 4 p.m. to be accompanied by someone 21 or older. One adult can chaperone up to four minors. The policy is part of the mall's broader security program, which includes the addition of metal detectors, more patrols and a K-9 unit. Malls that have policies prohibiting unaccompanied minors at any time are known as parental escort policies.

Curfews for adults

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Curfew" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

States and municipalities in the United States have occasionally enacted curfews on the population at large, often as a result of severely inclement weather or civil disorder. Some such curfews require all citizens simply to refrain from driving. Others require all citizens to remain inside, with exceptions granted to those in important positions, such as elected officials, law enforcement personnel, first responders, healthcare workers, and the mass media.

However, unlike juvenile curfews, all-ages curfews have always been very limited in terms of both location and duration. That is, they are temporary and restricted to very specific areas, and generally only implemented during states of emergency, then subsequently lifted or allowed to sunset.

In 1992, a curfew was imposed in Los Angeles, California during the Rodney King Riots.

In 2015, the city of Baltimore enacted a curfew on all citizens that lasted for five days and prohibited all citizens from going outdoors from 10 pm to 5 am with the exception of those traveling to or from work and those with medical emergencies. This was in response to the 2015 Baltimore protests.

During the global COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, local curfews were used (typically in combination with daytime lockdown policies) in the attempt to slow down the spread of the virus by limiting nonessential interactions between people from different households. Later in 2020, citywide curfews were enacted in major cities across the country due to protests following the killing of George Floyd in May. Arizona enacted a statewide curfew. Countywide curfews were enacted for Los Angeles County and Alameda County in California. In spring 2021, the city of Miami Beach, Florida enacted a citywide curfew due to public disorder associated with spring break celebrations.

See also

People

- Don A. Allen, member of the California State Assembly and of the Los Angeles City Council in the 1940s and 1950s, urged enforcement of curfew laws.

Notes

- ^ "Curfew Definition & Meaning". Dictionary.com. 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- "Definition of curfew". Oxford Dictionaries. 2012. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012.

- Hudson, David L. Jr. (3 June 2020) . "Curfews". The First Amendment Encyclopedia.

- "Curfew Laws". FindLaw.

- Brass, Paul R. (2006). "Collective Violence, Human Rights, and the Politics of Curfew". Journal of Human Rights. 5 (3): 323–340. doi:10.1080/14754830600812324. S2CID 35491331.

- Lerner, Kira (10 June 2020). "The Toll That Curfews Have Taken on Homeless Americans". The Appeal. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- Daventry, Michael (24 October 2020). "Curfews and restrictions imposed across Europe as COVID-19 cases soar". Euronews. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- Wood, Patrick (6 August 2020). "Why did Melbourne impose a curfew? It's not entirely clear". ABC News. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- de Haas, Samuel; Götz, Georg; Heim, Sven (2022). "Measuring the effect of COVID-19-related night curfews in a bundled intervention within Germany". Scientific Reports. 12 (1) 19732. Springer Nature: 19732. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1219732D. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-24086-9. PMC 9669542. PMID 36396710.

- Sprengholz, Philipp; Siegers, Regina; Goldhahn, Laura; Eitze, Sarah; Betsch, Cornelia (2021). "Good night: Experimental evidence that nighttime curfews may fuel disease dynamics by increasing contact density". Social Science & Medicine. 288: 114324. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114324. PMC 8426215. PMID 34419633.

- "Philippines: Curfew Violators Abused". Human Rights Watch. 26 March 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- Almomani, Ensaf Y.; Qablan, Ahmad M.; Almomany, Abbas M.; Atrooz, Fatin Y. (2021). "The coping strategies followed by university students to mitigate the COVID-19 quarantine psychological impact". Curr Psychol. 40 (11): 5772–5781. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-01833-1. ISSN 1046-1310. PMC 8106545. PMID 33994758.

- Bedoya Arguelles, Guadalupe; Dolinger, Amy; Dolkart, Caitlin Fitzgerald; Legovini, Arianna; Milusheva, Sveta; Marty, Robert Andrew; Taniform, Peter Ngwa (5 April 2023). The Unintended Consequences of Curfews on Road Safety (PDF) (Policy Research Working Paper). Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- Classen, Albrecht (15 December 2009). Urban Space in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Age. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-022390-3 – via Google Books.

- "curfew". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "Curfew". Bailey's dictionary (third ed.). 1726. p. 235.

- "Curfew". V&A Explore the Collections. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ Baldwin, Peter C. (Spring 2002). ""Nocturnal Habits and Dark Wisdom": The American Response to Children in the Streets at Night, 1880–1930". Journal of Social History. 35 (3): 593–611. doi:10.1353/jsh.2002.0002. S2CID 144849322.

- Doyle, Peter (July 2012). First World War Britain: 1914–1919. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7478-1129-9.

- "Pub and club curfew extended". Greenock Telegraph. 26 February 2010.

- "Night curfews in Victoria to drive down crime". The Herald Sun.

- "Coronavirus: Victoria declares state of disaster after spike in cases". BBC News. 2 August 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "Melbourne Covid curfew ends and restrictions ease, but Victoria introduces huge new fines". The Guardian. 27 September 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- Graham, Ben; Brown, Natalie (16 August 2021). "Live Breaking News: Melbourne's lockdown extended". ABC Melbourne. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- Taouk, Maryanne (20 August 2021). "Here are the new NSW COVID restrictions including a Sydney curfew, work permits and exercise limits". ABC Australia. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- "Phase 4: Belgium imposes curfew, closes bars, restricts contacts". The Brussels Times. 17 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- "Belgium imposes Covid curfew, closes bars and restaurants". Associated Press. 17 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- "7-hour curfew break in Dhaka, 3 other districts".

- Ellis-Petersen, Hannah (19 July 2024). "National curfew imposed in Bangladesh after student protesters storm prison". The Guardian.

- "Bangladesh unrest: Government imposes curfew as protests continue". www.bbc.com.

- Shih, Gerry (19 July 2024). "Bangladesh imposes curfew after dozens killed in anti-government protests". Washington Post. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- "Bangladesh imposes curfew, deploys army as job quota protests continue". Al Jazeera. No. 19 July 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- "Curfew continues in Bangladesh amid crackdown on protesters". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- "Bangladesh Imposes Strict Curfew With 'Shoot-On-Sight' Order Following Deadly Protests". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- "Confinement in Québec". www.quebec.ca. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- "Quebec reintroduces 10 p.m. curfew as infection rates skyrocket". CTV News. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- "Le couvre-feu n'a aucun effet sur le nombre de cas, estime l'IEDM". Le Journal de Montréal. Agence QMI. 5 January 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- Shenker, Jack; Beaumont, Peter; Jones, Sam (28 January 2011). "Egypt protests: Hosni Mubarak orders army to enforce curfew". The Guardian. London.

- Parks, Cara (29 January 2011). "Massive Egyptian Prison Break Frees 700 Inmates". Huffington Post.

- "Suez Canal residents defy President Morsi's curfew". ahram.org.eg.

- Matt Bradley (29 January 2013). "Egyptians Defy President's Curfew, as Unrest Spreads". WSJ.

- "No lockdown, no change to curfew – Koya".

- "Nationwide curfew to remain as Fiji fights COVID-19". Xinhua.

- James McAuley (14 October 2020). "Macron announces Paris curfew as coronavirus infections rise in France". The Washington Post. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Coronavirus: France to impose night-time curfew to battle second wave". BBC News. 14 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Paris Under Curfew: Europe Reacts As Countries See Highest-Ever Coronavirus Numbers". NPR. 14 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Curfew affecting 46 million people to take effect as France records 1 million COVID-19 cases". Euronews. 23 October 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- "Barnaverndarlög 2002 nr. 80 10. maí" [Child Protection Act 2002 no. 80 May 10th] (in Icelandic).

- Egan, Ríona. "Medieval Galway Exhibition – Galway City Museum Exhibitions".

- O'Connor, Dr Patrick J. (16 March 2003). Fairs and Markets of Ireland: A Cultural Geography. Oireacht na Mumhan Books. ISBN 978-0-9533896-3-6 – via Google Books.

- The Allen Library, Bro Allen Collection (16 March 1916). "Poster. Regulations to be observed under martial law (including curfew) in Dublin City and County". source.southdublinlibraries.ie.

- "Curfew imposed across Munster amid claims of police and military misconduct | Century Ireland". www.rte.ie.

- "The Limerick curfew murders". An Phoblacht.

- "The Limerick Curfew Murders 1921". Decade Of Centenaries. 10 January 2020.

- "Limerick Curfew Murders". Decade Of Centenaries. 10 January 2020.

- "Curfew in Dublin to be extended by one hour due to unrest | Century Ireland". www.rte.ie.

- O'Keeffe, Michelle. "Bail and curfew for youth who lives in Covid-19 positive house". The Irish Times.

- "Restriction on movement orders". www.citizensinformation.ie.

- "Types of sentences". www.citizensinformation.ie.

- "Coronavirus: coprifuoco in Lombardia, Campania e Lazio". Altalex. 22 October 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- "CORONAVIRUS, NUOVA ORDINANZA DI MUSUMECI PER LIMITARE IL CONTAGIO". 31 October 2020. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- "Gazzetta Ufficiale". www.gazzettaufficiale.it. 30 October 2020. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- "Gazzetta Ufficiale". www.gazzettaufficiale.it. 16 January 2021. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- "Gazzetta Ufficiale". www.gazzettaufficiale.it. 2 December 2020. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- "Gazzetta Ufficiale". www.gazzettaufficiale.it. 15 January 2021. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- "Coronavirus, il Presidente Conte firma il Dpcm del 3 november 2020" (PDF). 4 November 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- "Protests in Italy as coronavirus curfews come into force". 24 October 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- "Covid: Protests take place across Italy over anti-virus measures". BBC News. 27 October 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- "Morocco begins night curfew to curb the spread of Covid-19". Africanews. 24 December 2020. Archived from the original on 24 December 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- "Morocco: Authorities impose 20:00-06:00 curfew during Ramadan April 13-May 13 due to COVID-19 activity /update 59". GardaWorld. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- "Morocco: Authorities ease COVID-19 measures, including shortening nightly curfew, as of May 22 /update 63". GardaWorld. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- Kasraoui, Safaa (9 November 2021). "Morocco To Lift Night Curfew Tomorrow". Morocco World News. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- "Om 21.00 uur is de avondklok ingegaan, dit zijn de regels en uitzonderingen". Nederlandse Omroep Stichting. 23 January 2021.

- "5765 people fined for breaking curfew". NL Times. 26 January 2021.

- "Avondklok verlengd tot en met 2 maart, maar effect is nog niet duidelijk". Nederlandse Omroep Stichting. 8 February 2021.

- "Avondklok voor de laatste keer ingegaan" (in Dutch). 27 April 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- Bonnet, François-Xavier (4 May 2017). "From Oripun to the Yapayuki-San: An Historical Outline of Prostitution in the Philippines". Moussons. Recherche en sciences humaines sur l’Asie du Sud-Est (29): 41–64. doi:10.4000/moussons.3755. ISSN 1620-3224.

- Davis, George W. (1901). Report on the Military Government of the City of Manila, P.I., from 1898 to 1901. Headquarters Division of the Philippines. p. 9.

- "What If We Told You Today: Curfew Has Been Imposed in All Parts of the PH". Esquiremag.ph. 21 September 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- "Marcos Said to Approve Some Easing of Curfew". The New York Times. 4 December 1972. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- "22 August: Suspension of the Writ of Habeas Corpus (1971) and Lifting of Nightly Curfew and Travel Ban (1977)". Liberal Party of the Philippines. 22 August 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- "Martial Law's Nightly Curfew Was Lifted August 22, 1977". The Kahimyang Project. 22 August 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- "Duterte declares martial law in Mindanao". Philstar.com. 23 May 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- Jennings, Ralph (13 December 2017). "Filipinos Find Gains, No Pain Under Martial Law". Voice of America. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- "Philippines' Duterte planning curfews on children, alcohol: Aide". The Straits Times. 10 May 2016. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- Ranada, Pia (16 May 2016). "Duterte: Curfew for minors in, late-night karaoke out". RAPPLER. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- "ORDINANCE No. 8046 – City Council of Manila". Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- "Ordinance No. 2491 - Sangguniang Panlungsod, City of Davao" (PDF). www.iccwtnispcanarc.org.

- "P.D. No. 603". lawphil.net. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- "House bill seeks 10 p.m. national curfew for minors". Philstar.com. 7 August 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- "House Bill No. 1016, 19th Congress | Senate of the Philippines Legislative Reference Bureau". issuances-library.senate.gov.ph. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ Divina, Nilo (21 December 2023). "Constitutionality of curfew for minors". Daily Tribune. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- "Philippines to expand Covid curbs beyond capital amid surge". Bangkok Post. 21 March 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- Saavedra, John Rey (15 March 2020). "Cebu imposes curfew, strict travel control". www.pna.gov.ph. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- Rosauro, Ryan D. (5 November 2021). "Curfew shortened in Cagayan de Oro as virus threat eases". INQUIRER.net. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- "Policijska ura prvič po italijanski okupaciji" [Curfew For the First Time After the Italian Occupation]. Dnevnik (in Slovenian). 19 October 2020.

- Hladner Hvala, Tadeja (20 October 2020). "Sprehajanje psov lahko štejemo kot nujno opravilo" [Walking dogs can be considered an essential task]. Žurnal.si (in Slovenian).

- Cirman, Primož; Modic, Tomaž; Vuković, Vesna (17 June 2021). "Skupina Bojane Beović je bila "nepotrebna in neustrezna"" [Bojana Beović's Group was "Unnecessary and Inadequate"]. Necenzurirano.si (in Slovenian).

- "O policijski uri med epidemijo ustavno sodišče vsebinsko ne bo presojalo" [The Constitutional Court Will Not Rule on the Substance of the Curfew During the Epidemic]. Portal TAX-FIN-LEX (in Slovenian). 17 April 2023.

- Tracy Dahl (18 January 1982). "S. Koreans Enjoy Nights Without Curfew". The Washington Post.

- "Sánchez decreta un nuevo estado de alarma que quiere prolongar hasta el 9 de mayo". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 25 October 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- "Чому на Закарпатті немає комендантської години і як область живе без обмежень". BBC Ukraine (in Ukrainian). 20 October 2022.

- "BBC NEWS – UK – England – Wear – Late night youth curfew a success". bbc.co.uk. 4 October 2006.

- "Court Judgment on Government's 'Anti-Yob'/ Anti-Child Policy". liberty-human-rights.org.uk. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- "St. Peter's Shared Church Chertsey". stpeterschertsey.org.uk. 12 March 2015.

- "peak district local history, customs, wildlife, transport – Peakland Heritage". peaklandheritage.org.uk. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ^ Simpson, Claire (24 December 2020). "Police to have powers to enforce post-Christmas curfew". The Irish News.

- Simpson, Claire (19 December 2020). "Post-Christmas lockdown will see 'curfew' for a week". The Irish News.

- "Curfews in New York · 411 NY". 411newyork.org.

- Curfew put in place for all US troops in South Korea, Stars and Stripes, 2011, archived from the original on 1 August 2020, retrieved 12 February 2012

- "Town of Myersville, MD Curfew". ecode360.com.

- Moore, Timothy J.; Morris, Todd (2024). "Shaping the Habits of Teen Drivers". American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 16 (3): 367–393. doi:10.1257/pol.20220403. ISSN 1945-7731.

- "Curfews » City of Faribault, MN". faribault.org. Archived from the original on 9 May 2012.

- "Impact of juvenile curfew laws on arrests of youth and adults". 29 November 2011.

- Mike Males (14 October 2013). "OP-ED: Why Don't Youth Curfews Work?".

- Jennifer L. Doleac (29 December 2015). "Repealing juvenile curfew laws could make cities safer".

- Duggan, James Lawler (1 August 2018). "Why Juvenile Curfews Don't Work". The Marshall Project.

- "New Orleans curfew data: 93 percent of curfew arrestees are black". NOLA.com. 29 March 2013.

- "Frequently Asked Questions about the County Executive's Youth Curfew Proposal" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- "Upscale Mall Enforces Teen Curfew & Dress Code". cbslocal.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- "Code of Conduct – NorthPark Center". northparkcenter.com.

- "Parental Escort Policy". mallofamerica.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

External links

The dictionary definition of curfew at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of curfew at Wiktionary Media related to Curfews at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Curfews at Wikimedia Commons- BBC Report on legal challenge to curfew laws

- Juvenile Curfews TELEMASP Bulletin, Texas Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics Program

- "Curfew" . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.