Shrapnel shells were anti-personnel artillery munitions that carried many individual bullets close to a target area and then ejected them to allow them to continue along the shell's trajectory and strike targets individually. They relied almost entirely on the shell's velocity for their lethality. The munition has been obsolete since the end of World War I for anti-personnel use; high-explosive shells superseded it for that role. The functioning and principles behind shrapnel shells are fundamentally different from high-explosive shell fragmentation. Shrapnel is named after Lieutenant-General Henry Shrapnel, a Royal Artillery officer, whose experiments, initially conducted on his own time and at his own expense, culminated in the design and development of a new type of artillery shell.

Usage of the term "shrapnel" has changed over time to also refer to fragmentation of the casing of shells and bombs, which is its most common modern usage and strays from the original meaning.

Development

In 1784, Lieutenant Shrapnel of the Royal Artillery began developing an anti-personnel weapon. At the time, artillery could use "canister shot" to defend themselves from infantry or cavalry attack, which involved loading a tin or canvas container filled with small iron or lead balls instead of the usual cannonball. When fired, the container burst open during passage through the bore or at the muzzle, giving the effect of an oversized shotgun shell. At ranges of up to 300 m canister shot was still highly lethal, though at this range the shots’ density was much lower, making a hit on a human body less likely. At longer ranges, solid shot or the common shell—a hollow cast-iron sphere filled with black powder—was used, although with more of a concussive than a fragmentation effect, as the pieces of the shell were very large and sparse in number.

Shrapnel's innovation was to combine the multi-projectile shotgun effect of canister shot, with a time fuse (“fuze” rather than “fuse” is more accurate terminology for a device that initiates an explosive) to open the canister and disperse the shot it contained at some distance along the canister's trajectory from the gun. His shell was a hollow cast-iron sphere filled with a mixture of balls (“shot”) and powder, with a crude time fuze. If the fuze was set correctly then the shell would break open, either in front of or above the intended human objective, releasing its contents (of musket balls). The shrapnel balls would carry on with the "remaining velocity" of the shell. In addition to a denser pattern of musket balls, the retained velocity could be higher as well, since the shrapnel shell as a whole would likely have a higher ballistic coefficient than the individual musket balls (see external ballistics).

The explosive charge in the shell was to be just enough to break the casing rather than scatter the shot in all directions. As such his invention increased the effective range of canister shot from 300 metres (980 ft) to about 1,100 metres (3,600 ft).

He called his device 'spherical case shot', but in time it came to be called after him; a nomenclature formalised in 1852 by the British Government.

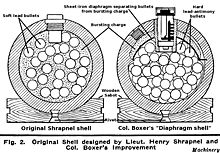

Initial designs suffered from the potentially-catastrophic problem that friction between the shot and black powder during the high acceleration down the gun bore could sometimes cause premature ignition of the powder. Various solutions were tried with limited, if any, success. However, in 1852, Colonel Boxer proposed using a diaphragm to separate the bullets from the bursting charge, which proved successful and was adopted the following year. As a buffer to prevent lead shot deforming, a resin was used as a packing material between the shot. A useful side effect of using the resin was that the combustion also gave a visual reference upon the shell bursting, as the resin shattered into a cloud of dust.

British artillery adoption

It took until 1803 for the British artillery to adopt (albeit with great enthusiasm) the shrapnel shell (as "spherical case"). Henry Shrapnel was promoted to major in the same year. The first recorded use of shrapnel by the British was in 1804 against the Dutch at Fort Nieuw-Amsterdam in Suriname. The Duke of Wellington's armies used it from 1808 in the Peninsular War and at the Battle of Waterloo, and he wrote admiringly of its effectiveness.

The design was improved by Captain E. M. Boxer of the Royal Arsenal around 1852 and crossed over when cylindrical shells for rifled guns were introduced. Lieutenant-Colonel Boxer adapted his design in 1864 to produce shrapnel shells for the new rifled muzzle-loader (RML) guns: the walls were of thick cast iron, but the gunpowder charge was now in the shell base with a tube running through the centre of the shell to convey the ignition flash from the time fuse in the nose to the gunpowder charge in the base. The powder charge both shattered the cast iron shell wall and liberated the bullets. The broken shell wall continued mainly forward but had little destructive effect. The system had major limitations: the thickness of the iron shell walls limited the available carrying capacity for bullets but provided little destructive capability, and the tube through the centre similarly reduced available space for bullets.

In the 1870s, William Armstrong provided a design with the bursting charge in the head and the shell wall made of steel and hence much thinner than previous cast-iron shrapnel shell walls. While the thinner shell wall and absence of a central tube allowed the shell to carry far more bullets, it had the disadvantage that the bursting charge separated the bullets from the shell casing by firing the case forward and at the same time slowing the bullets down as they were ejected through the base of the shell casing, rather than increasing their velocity. Britain adopted this solution for several smaller calibres (below 6-inch) but by World War I few if any such shells remained.

The final shrapnel shell design, adopted in the 1880s, bore little similarity to Henry Shrapnel's original design other than its spherical bullets and time fuse. It used a much thinner forged steel shell case with a timer fuse in the nose and a tube running through the centre to convey the ignition flash to a gunpowder bursting charge in the shell base. The use of steel allowed a thinner shell wall, allowing space for many more bullets. It also withstood the force of the powder charge without shattering so that the bullets were fired forward out of the shell case with increased velocity, much like a shotgun. The design came to be adopted by all countries and was in standard use when World War I began in 1914. During the 1880s, when both the old cast-iron and modern forged-steel shrapnel shell designs were in British service, British ordnance manuals referred to the older cast-iron design as "Boxer shrapnel", apparently to differentiate it from the modern steel design.

The modern thin-walled forged-steel design made feasible shrapnel shells for howitzers, which had a much lower velocity than field guns, by using a larger gunpowder charge to accelerate the bullets forward on bursting. The ideal shrapnel design would have had a timer fuse in the shell base to avoid the need for a central tube, but that was not technically feasible because of the need for manually adjust the fuse before firing and was in any case rejected from an early date by the British because of risk of premature ignition and irregular action.

World War I era

1 Gunpowder bursting charge

2 Bullets

3 Time fuze

4 Ignition tube

5 Resin holding bullets in position

6 Steel shell wall

7 Cartridge case

8 Shell propellant

Technical considerations

The size of shrapnel balls in World War I was based on two considerations. One was the premise that a projectile energy of about 60 foot-pounds force (81 J) was required to disable an enemy soldier. A typical World War I 3-inch (76 mm) field gun shell at its maximum possible range traveling at a velocity of 250 feet/second, plus the additional velocity from the shrapnel bursting charge (about 150 feet per second), would give individual shrapnel bullets a velocity of 400 feet per second and an energy of 60 foot-pounds (81 joules): this was the minimum energy of a single half-inch lead-antimony ball of approximately 170 grains (11 g), or 41–42 balls = 1 pound. Hence this was a typical field gun shrapnel bullet size.

The maximum possible range, typically beyond 7,000 yards (6,400 m), was beyond useful shrapnel combat ranges for normal field guns due to loss of accuracy and the fact that at extreme range the projectiles descended relatively steeply and hence the "cone" of bullets covered a relatively small area.

At a more typical combat range of 3,000 yards (2,700 m), giving a fairly flat trajectory and hence a long "beaten zone" for the bullets, a typical 3-inch or 75-mm field gun shrapnel shell would have a velocity of approximately 900 feet/second. The bursting charge would add a possible 150 feet/second, giving a bullet velocity of 1,050 feet/second. This would give each bullet approximately 418 foot-pounds: seven times the assumed energy required to disable a man.

For larger guns which had lower velocities, correspondingly larger balls were used so that each individual ball carried enough energy to be lethal.

Most engagements using guns in this size range used direct fire at enemy from 1,500 yards (1,400 m) to 3,000 yards (2,700 m) distant, at which ranges the residual shell velocity was correspondingly higher, as in the table – at least in the earlier stages of World War 1.

The other factor was the trajectory. The shrapnel bullets were typically lethal for about 300 yards (270 m) from normal field guns after bursting and over 400 yards (370 m) from heavy field guns. To make maximum use of these distances a flat-trajectory and hence high-velocity gun was required. The pattern in Europe was that the armies with higher-velocity guns tended to use heavier bullets because they could afford to have fewer bullets per shell.

The important points to note about shrapnel shells and bullets in their final stage of development in World War I are:

- They used the property of carrying power, whereby if two projectiles are fired with the same velocity, then the heavier one goes farther. Bullets packed into a heavier carrier shell went farther than they would individually.

- The shell body itself was not designed to be lethal: its sole function was to transport the bullets close to the target, and it fell to the ground intact after the bullets were released. A battlefield where a shrapnel barrage had been fired was afterwards typically littered with intact empty shell bodies, fuses and central tubes. Troops under a shrapnel barrage would attempt to convey any of these intact fuses they found to their own artillery units, as the time setting on the fuse could be used to calculate the shell's range and hence identify the firing gun's position, allowing it to be targeted in a counter-barrage.

- They depended almost entirely on the shell's velocity for their lethality: there was no lateral explosive effect.

A firsthand description of successful British deployment of shrapnel in a defensive barrage during the Third Battle of Ypres, 1917:

... the air is full of yellow spurts of smoke that burst about 30 feet up and shoot towards the earth – just ahead of each of these yellow puffs the earth rises in a lashed-up cloud – shrapnel – and how beautifully placed – long sweeps of it fly along that slope lashing up a good 200 yards of earth at each burst.

Tactical use

The spherical bullets are visible in the sectioned shell (top left), and the cordite propellant in the brass cartridge is simulated by a bundle of cut string (top right). The nose fuse is not present in the sectioned round at top but is present in the complete round below. The tube through the centre of the shell is visible, which conveyed the ignition flash from the fuse to the small gunpowder charge in the cavity visible here in the base of the shell. This gunpowder charge then exploded and propelled the bullets out of the shell body through the nose.

During the initial stages of World War I, shrapnel was widely used by all sides as an anti-personnel weapon. It was the only type of shell available for British field guns (13-pounder, 15 pounder and 18-pounder) until October 1914. Shrapnel was effective against troops in the open, particularly massed infantry (advancing or withdrawing). However, the onset of trench warfare from late 1914 led to most armies decreasing their use of shrapnel in favour of high-explosive. Britain continued to use a high percentage of shrapnel shells. New tactical roles included cutting barbed wire and providing "creeping barrages" to both screen its own attacking troops and suppressing the enemy defenders to prevent them from shooting at their attackers.

In a creeping barrage fire was 'lifted' from one 'line' to the next as the attackers advanced. These lines were typically 100 yards (91 m) apart and the lifts were typically 4 minutes apart. Lifting meant that time fuses settings had to be changed. The attackers tried to keep as close as possible (as little as 25 yards sometimes) to the bursting shrapnel so as to be on top of the enemy trenches when fire lifted beyond them, and before the enemy could get back to their parapets.

Advantages

While shrapnel made no impression on trenches and other earthworks, it remained the favoured weapon of the British (at least) to support their infantry assaults by suppressing the enemy infantry and preventing them from manning their trench parapets. This was called 'neutralization' and by the second half of 1915 had become the primary task of artillery supporting an attack. Shrapnel was less hazardous to the assaulting British infantry than high-explosives – as long as their own shrapnel burst above or ahead of them, attackers were safe from its effects, whereas high-explosive shells bursting short are potentially lethal within 100 yards or more in any direction. Shrapnel was also useful against counter-attacks, working parties and any other troops in the open.

British Expeditionary Force "GHQ Artillery Notes No. 5 Wire-cutting" was issued in June 1916. It prescribed the use of shrapnel for wirecutting, with HE used to scatter the posts and wire when cut. However, there were constraints: the best ranges for 18-pdrs were 1,800–2,400 yards. Shorter ranges meant the flat trajectories might not clear the firers' own parapets, and fuses could not be set for less than 1,000 yards. The guns had to be overhauled by artificers and carefully calibrated. Furthermore, they needed good platforms with trail and wheels anchored with sandbags, and an observing officer had to monitor the effects on the wire continuously and make any necessary adjustments to range and fuse settings. These instructions were repeated in "GHQ Artillery Notes No. 3 Artillery in Offensive Operations", issued in February 1917 with added detail including the amount of ammunition required per yard of wire frontage. The use of shrapnel for wire-cutting was also highlighted in RA "Training Memoranda No. 2 1939".

Shrapnel provided a useful "screening" effect from the smoke of the black-powder bursting charges when the British used it in "creeping barrages".

Disadvantages

One of the key factors that contributed to the heavy casualties sustained by the British at the Battle of the Somme was the perceived belief that shrapnel would be effective at cutting the barbed wire entanglements in no man's land (although it has been suggested that the reason for the use of shrapnel as a wire-cutter at the Somme was because Britain lacked the capacity to manufacture enough HE shell). This perception was reinforced by the successful deployment of shrapnel shells against Germany's barbed wire entanglements in the 1915 Battle of Neuve Chapelle, but the Germans thickened their barbed wire strands after that battle. As a result, shrapnel was later only effective in killing enemy personnel; even if the conditions were correct, with the angle of descent being flat to maximise the number of bullets going through the entanglements, the probability of a shrapnel ball hitting a thin line of barbed wire and successfully cutting it was extremely low. The bullets also had limited destructive effect and were stopped by sandbags, so troops behind protection or in bunkers were generally safe. Additionally, steel helmets, including both the German Stahlhelm and the British Brodie helmet, could resist shrapnel bullets and protect the wearer from head injury:

... suddenly, with a great clanging thud, I was hit on the forehead and knocked flying onto the floor of the trench... a shrapnel bullet had hit my helmet with great violence, without piercing it, but sufficiently hard to dent it. If I had, as had been usual up until a few days previously, been wearing a cap, then the Regiment would have had one more man killed.

A shrapnel shell was more expensive than a high-explosive one and required higher-grade steel for the shell body. They were also harder to use correctly because getting the correct fuse running time was critical in order to burst the shell in the right place. This required considerable skill by the observation officer when engaging moving targets.

An added complication was that the actual fuse running time was affected by the meteorological conditions, with the variation in gun muzzle velocity being an added complication. However, the British used fuse indicators at each gun that determined the correct fuse running time (length) corrected for muzzle velocity.

Replacement by high-explosive shell

With the advent of relatively insensitive high explosives which could be used as the filling for shells, it was found that the casing of a properly designed high-explosive shell fragmented effectively . For example, the detonation of an average 105 mm shell produces several thousand high-velocity (1,000 to 1,500 m/s) fragments, a lethal (at very close range) blast overpressure and, if a surface or sub-surface burst, a useful cratering and anti-materiel effect – all in a munition much less complex than the later versions of the shrapnel shell. However, this fragmentation was often lost when shells penetrated soft ground, and because some fragments went in all directions it was a hazard to assaulting troops.

Variations

One item of note is the "universal shell", a type of field gun shell developed by Krupp of Germany in the early 1900s. This shell could function as either a shrapnel shell or high-explosive projectile. The shell had a modified fuse, and, instead of resin as the packing between the shrapnel balls, TNT was used. When a timed fuse was set the shell functioned as a shrapnel round, ejecting the balls and igniting (not detonating) the TNT, giving a visible puff of black smoke. When allowed to impact, the TNT filling would detonate, becoming a high-explosive shell with a very large amount of low-velocity fragmentation and a milder blast. Due to its complexity it was dropped in favour of a simple high-explosive shell.

During World War I the UK also used shrapnel pattern shells to carry "pots" instead of "bullets". These were incendiary shells with seven pots using a thermite compound.

When World War I began the United States also had what it referred to as the "Ehrhardt high-explosive shrapnel" in its inventory. It appears to be similar to the German design, with bullets embedded in TNT rather than resin, together with a quantity of explosive in the shell nose. Douglas Hamilton mentions this shell type in passing, as "not as common as other types" in his comprehensive treatises on manufacturing shrapnel and high-explosive shells of 1915 and 1916, but gives no manufacturing details. Nor does Ethan Viall in 1917. Hence the US appears to have ceased its manufacture early in the war, presumably based on the experience of other combatants.

World War II era

A new British streamlined shrapnel shell, Mk 3D, had been developed for BL 60 pounder gun in the early 1930s, containing 760 bullets. There was some use of shrapnel by the British in the campaigns in East and North East Africa at the beginning of the war, where 18-pdr and 4.5-in (114 mm) howitzers were used. By World War II shrapnel shells, in the strict sense of the word, fell out of use, the last recorded use of shrapnel being 60 pdr shells fired in Burma in 1943. In 1945 the British conducted successful trials with shrapnel shells fused with VT. However, shrapnel was not developed as munitions for any new British artillery models after World War I.

Vietnam War era

Although not strictly shrapnel, a 1960s weapons project produced splintex shells for 90 and 106 mm recoilless rifles and 105 mm howitzers, where it was called a "beehive" round. Unlike the shrapnel shells’ balls, the splintex shells contained flechettes. The result was the 105 mm M546 APERS-T (anti-personnel-tracer) round, first used in the Vietnam War in 1966. The shell consisted of approximately 8,000 one-half-gram flechettes arranged in five tiers, a time fuse, body-shearing detonators, a central flash tube, a smokeless propellant charge with a dye marker contained in the base and a tracer element. The shell functioned as follows: the time fuse fired, the flash traveled down the flash tube, the shearing detonators fired, and the forward body split into four pieces. The body and first four tiers were dispersed by the projectile's spin, the last tier and visual marker by the powder charge itself. The flechettes spread, mainly due to spin, from the point of burst in an ever-widening cone along the projectile's previous trajectory prior to bursting. The round was complex to make, but is a highly effective anti-personnel weapon – soldiers reported that after beehive rounds were fired during an overrun attack, many enemy dead had their hands nailed to the wooden stocks of their rifles, and these dead could be dragged to mass graves by the rifle. It is said that the name beehive was given to the munition type due to the noise of the flechettes moving through the air resembling that of a swarm of bees.

Modern era

Though shrapnel rounds are now rarely used, apart from the beehive munitions, there are other modern rounds, that use, or have used, the shrapnel principle. The DM 111 20 mm cannon round used for close-range air defense, the flechette-filled 40 mm HVCC (40 x 53 mm HV grenade), the 35 mm cannon (35 × 228 mm) AHEAD ammunition (152 × 3.3 g tungsten cylinders), RWM Schweiz 30 × 173 mm air-bursting munition, five-inch (127 mm) shotgun projectile (KE-ET) and possibly more. Also, many modern armies have canister shot ammunition for tank and artillery guns, the XM1028 round for the 120 mm M256 tank gun being one example (approx 1150 tungsten balls at 1,400 m/s).

Some anti-ballistic missiles (ABMs) use shrapnel-like warheads instead of the more common blast-fragmentation types. As with a blast-frag warhead, the use of this type of warhead does not require a direct body-on-body impact, so greatly reduces tracking and steering accuracy requirements. At a predetermined distance from the incoming re-entry vehicle (RV) the warhead releases, in the case of the ABM warhead by an explosive expulsion charge, an array of mainly rod-like sub-projectiles into the RV's flight path. Unlike a blast-frag warhead, the expulsion charge is only needed to release the sub-projectiles from the main warhead, not to accelerate them to high velocity. The velocity required to penetrate the RV's casing comes from the high terminal velocity of the warhead, similar to the shrapnel shell's principle. The reason for the use of this type of warhead and not a blast-frag is that the fragments produced by a blast-frag warhead cannot guarantee penetration of the RV's casing. By using rod-like sub-projectiles, a much greater thickness of material can be penetrated, greatly increasing the potential for disruption of the incoming RV.

The Starstreak missile uses a similar system, with three metal darts splitting from the missile prior to impact, although in the case of Starstreak these darts are guided and contain an explosive charge.

Gallery of images

-

US, Russian, German, French & British WWI Shrapnel rounds compared

US, Russian, German, French & British WWI Shrapnel rounds compared

-

British 18-pounder shrapnel shell, WWI

British 18-pounder shrapnel shell, WWI

-

Shrapnel ball from WWI recovered at Verdun

Shrapnel ball from WWI recovered at Verdun

-

Empty fired shrapnel shells at Sanctuary Wood, Belgium

Empty fired shrapnel shells at Sanctuary Wood, Belgium

See also

Notes

- Foot-pounds are calculated as wv/2gc, where gc is the local acceleration of gravity, or 32.16 ft/second. Hence for the British calculation: 60 foot-pounds = 1/41 × v/64.32 . Hence v = 60 × 64.32 × 41 . Hence v = 398 feet/second

References

- Vetch, Robert Hamilton (1897). "Shrapnel, Henry" . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 52. pp. 163–165.

- "What is the difference between artillery shrapnel and shell fragments?". Combat Forces Journal. March 1952. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017.

- Hogg p. 180.

- Marshall, 1920.

- ^ "The action of Boxer-shrapnel is well known. The fuse fires the primer, which conveys the flash down the pipe to the bursting charge, the explosion of which breaks up the shell, and liberates the balls". Treatise on Ammunition 1887, p. 216.

- ^ "Treatise on Ammunition", 4th Edition 1887, pp. 203–205.

- ^ Treatise on Ammunition 1887, p. 205.

- Lt-Col. Ormond M Lissak, Ordnance and Gunnery. A Text-Book. New York: John Wiley, 1915. Page 446

- Treatise on Ammunition, 10th Edition, 1915. War Office, UK. Page 173.

- Bethel p. 124.

- Lieutenant Cyril Lawrence, 1st Field Company, Australian Engineers. Quoted in "Passchendaele. The Sacrificial Ground" by Nigel Steel and Peter Hart, published by Cassell Military Paperbacks, London, 2001, page 232. ISBN 978-0-304-35975-2

- Canadian War Museum (July 2024). "Shrapnel Bullets" (PDF).

- Keegan, The Face of Battle

- Reserve Lieutenant Walter Schulze of 8th Company Reserve Infantry Regiment 76, German Army, described his combat introduction to the Stahlhelm on the Somme, 29 July 1916. Quoted in Sheldon, German Army on the Somme, page 219. Sheldon quotes and translates from Gropp, History of IR 76, p 159.

- "Frequentely Asked Questions - Artillery Shrapnel and Shell Fragments". history.army.mil. Retrieved 2024-07-04.

- Hogg p. 173.

- E.L. Gruber, "Notes on the 3 inch gun materiel and field artillery equipment". New Haven Print. Co., 1917

- Douglas T Hamilton, "Shrapnel Shell Manufacture. A Comprehensive Treatise". New York: Industrial Press, 1915

- Douglas T Hamilton, "High-explosive shell manufacture; a comprehensive treatise". New York: Industrial Press, 1916

- Ethan Viall, "United States artillery ammunition; 3 to 6 in. shrapnel shells, 3 to 6 in. high explosive shells and their cartridge cases". New York, McGraw-Hill book company, 1917.

- Tucker, Spencer (2015). Instruments of war : weapons and technologies that have changed history. Santa Barbara, CA. ISBN 978-1-4408-3654-1. OCLC 899880792.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Sources

- Bethel, HA. 1911. Modern Artillery in the Field – a description of the artillery of the field army, and the principles and methods of its employment. London: Macmillan and Co Limited

- Hogg, OFG. 1970. Artillery: its origin, heyday and decline. London: C. Hurst & Company.

- Keegan, John. The Face of Battle. London: Jonathan Cape, 1976. ISBN 0-670-30432-8

- A. MARSHALL, F.I.C. (Chemical Inspector, Indian Ordnance Department), "The Invention and Development of the Shrapnel Shell" from Journal of the Royal Artillery, January, 1920 Archived 2011-06-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Sheldon, Jack (2007). The German Army on the Somme 1914–1916. Barnsley, South York, UK: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-513-2. OCLC 72868781.

External links

- Douglas T Hamilton, Shrapnel Shell Manufacture. A Comprehensive Treatise. New York: Industrial Press, 1915

- Various authors, "Shrapnel and other war material" : Reprint of articles in American Machinist New York : McGraw-Hill, 1915