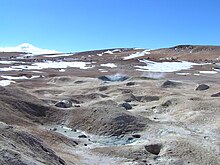

Geothermally active area in southern Bolivia

| Sol de Mañana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Highest point | |

| Coordinates | 22°25′35″S 67°45′35″W / 22.42639°S 67.75972°W / -22.42639; -67.75972 |

| Geography | |

| |

Sol de Mañana is an area with geothermal manifestations in southern Bolivia, including fumaroles, hot springs and mud pools. It lies at about 4,900 metres (16,100 ft) elevation, south of Laguna Colorada and east of El Tatio geothermal field. The field is located within the Eduardo Avaroa Andean Fauna National Reserve and is an important tourism attraction on the road between Uyuni and Antofagasta. The field has been prospected as a possible geothermal power production site, with research beginning in the 1970s and after a pause recommencing in 2010. Development is ongoing as of 2023.

Description

Sol de Mañana lies in the San Pablo de Lipez municipality (Sud Lipez Province), in a remote and uninhabited region of Bolivia. In an area of 10 square kilometres (3.9 sq mi) there are steam vents, mud pools, hot springs, geysers and fumaroles. Apart from Sol de Mañana proper there are additional geothermal manifestations dispersed a few kilometres south-southwest at Apacheta and 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) from Sol de Mañana; north-northwest at Huayllajara; The first two feature hydrothermally altered rocks and sometimes they are considered to be separate geothermal fields.

Steam/water emissions can under exceptional circumstances reach heights of 200 metres (660 ft). Gas vents release sulfur-containing gases. The temperatures of the springs reach 30 °C (86 °F) and the fumaroles 70 °C (158 °F), hot enough to be visible from space in ASTER images. Seismic swarms and earthquakes have been recorded in the field. Sol de Mañana lies at about 4,900 metres (16,100 ft) elevation, making it among the highest geothermal fields in the world.

The nearest major communities are Quetena Grande and Quetena Chico in Bolivia, 75 kilometres (47 mi) northeast from Sol de Mañana, and the field can be accessed through unpaved roads from Uyuni, 340 kilometres (210 mi) away. 30 kilometres (19 mi) across the frontier, in Chile, lies El Tatio, the best-known geothermal manifestation in the Central Andes. There are numerous volcanoes in the area, including Tocorpuri west-southwest and Putana and Escalante southwest of Sol de Mañana, and the Pastos Grandes and Cerro Guacha caldera systems. The field lies 40 kilometres (25 mi)-20 kilometres (12 mi) south of Laguna Colorada, which can be reached from Sol de Mañana. There are mines at Cerro Aguita Blanca, a few kilometres south of Sol de Mañana, and at Cerro Apacheta about five kilometres west-southwest; the latter can be reached through another road from Sol de Mañana.

Panorama of the Sol de Mañana mudpools

Panorama of the Sol de Mañana mudpools

Geology

Off the western coast of South America, the Nazca Plate subducts beneath the South American Plate. The subduction is responsible for the volcanism of the Andes. The growth of the Altiplano high plateau commenced 25 million years ago before shifting eastward 12-6 million years ago.

The Andean Central Volcanic Zone is one of four belts of volcanoes in the Andes. Volcanic activity began 23 million years ago and involved the emplacement of a series of ignimbrites, which form one of the largest ignimbrite plateaus of the world. Numerous younger stratovolcanoes grew on top of the ignimbrites; there are about 150 separate volcanic centres. The Altiplano volcanoes form the Altiplano-Puna volcanic complex, which is underpinned by the Altiplano-Puna Magma Body. The dry climate leads to an exceptional preservation of the volcanic landforms. About 50 volcanoes in the Central Andes (Bolivia, northern Chile, northern Argentina) were active during the Holocene.

Local

Sol de Mañana is part of the Laguna Colorada geothermal area/caldera complex (the names are sometimes used interchangeably). The area features Miocene-Pleistocene volcanic rocks (dacite forming ignimbrites, lavas and tuffs) emplaced on top of Cenozoic marine sediments. Alluvial deposits and moraines occur in the area. There are various north-south and northwest–southeast trending tectonic lineaments in the region, associated with rock deformation. At Sol de Mañana there are a number of faults, including normal faults active during the Holocene, which constitute pathways for the ascent of hot water. The most important faults at the field trend north-northwest-south-southeast. Glacial erosion has taken place in the area during the past, which has left moraines east and north-northwest of Sol de Mañana.

Drill cores have identified several rock units under Sol de Mañana, including several layers of dacitic ignimbrites with ages of about 5-1.2 million years and andesitic lavas. Hydrothermal alteration has taken place throughout the layers, forming from top to bottom layers rich clays, silica and epidote; each of these layers is several hundred metres thick. Basement rocks were not encountered. This stratigraphy is similar to that at El Tatio, across the border in Chile. The geothermal heat reservoir appears to be located within the ignimbrites and andesites.

The heat may originate either in the Altiplano-Puna Magma Body or in the volcanic arc. It is transported upward through convection, forming two heat reservoirs underground that are capped by a clay layer. Precipitation water reaches the reservoirs through deep faults, which also allow heat circulation. Drilling has shown that the reservoirs have temperatures of about 250–260 °C (482–500 °F). The Sol de Mañana geothermal system may be physically connected to El Tatio, with Sol de Mañana being closer to the heat source and Tatio an outflow at lower elevation.

Climate and ecosystem

There is a weather station on Sol de Mañana. Mean annual precipitation is about 75 millimetres (3.0 in) and mean temperatures are about 8.9 °C (48.0 °F). The geothermal field is part of the Eduardo Avaroa Andean Fauna National Reserve and one of the main tourism attractions on the Uyuni-Antofagasta road.

Geothermal power generation

The 1973 oil crisis created the impetus for increased investigation of Bolivia's geothermal power resources, focusing on the Altiplano and the surrounding Andean ranges. Prospecting by the National Electricity Company and the state agency for geology identified Sajama, Salar de Empexa and Laguna Colorada as the most suitable areas for geothermal power generation. A geothermal project began in 1978 and numerous drilling operations were undertaken in the following years; however development ceased in 1993 as the legal and political circumstances were unfavourable. A renewed effort began in 2010, spearheaded by the Japan International Cooperation Agency, during which additional cores were drilled, but as of 2023 is still at its early stages and as of 2016 is only used as process heat for the San Cristobal mine. An electrical power potential of about 50–100 megawatts (67,000–134,000 hp) has been estimated.

Laguna Colorada/Sol de Mañana are the main focus of geothermal power prospecting in Bolivia; other sites have drawn scarce interest. As of 2016 Bolivia did not have any legislation specific for geothermal power generation. Geothermal power development is also hindered by the remote location, which would require building large power transmission networks, and the low price of electricity in the country.

Notes

- The Altiplano-Puna Magmatic Body is an accumulation of magma in the crust of the Altiplano.

- Including the Tara Ignimbrite from a supereruption of Cerro Guacha.

References

- ^ USGS 1992, p. 267.

- Communication Ministry 2020.

- ^ Bona & Coviello 2016, p. 35.

- ^ De Silva & Francis 1991, p. 170.

- Damir 2014, p. 156.

- ^ Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 4.

- ^ De Silva & Francis 1991, p. 171.

- Sullcani 2015, p. 668.

- ^ Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 1.

- Pritchard et al. 2014, p. 98.

- ^ Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 2.

- Müller et al. 2022, p. 3.

- ^ Suaznabar, Quiroga & Villarreal 2019, p. 2.

- ^ Bona & Coviello 2016, p. 38.

- Delgadillo & Puente 1998, p. 257.

- Fernandez-Turiel et al. 2005, p. 127.

- Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 8.

- ^ Ministry of Hydrocarbons and Energies 2022, p. 183.

- ^ Sullcani 2015, p. 666.

- ^ Sullcani 2015, p. 667.

- ^ Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 3.

- Pritchard et al. 2014, p. 90.

- Fernandez-Turiel et al. 2005, p. 128.

- Ort 2009, p. 1.

- ^ Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 5.

- Delgadillo & Puente 1998, p. 258.

- Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, pp. 5–6.

- Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 19.

- Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 15.

- Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 17.

- Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, p. 18.

- Cortecci et al. 2005, p. 568.

- De Silva & Francis 1991, p. 172.

- Lagos et al. 2023, p. 5.

- Pereyra Quiroga et al. 2023, pp. 1–2.

- Bona & Coviello 2016, p. 36.

Sources

- Bona, Paolo; Coviello, Manlio (April 2016). Valoración y gobernanza de los proyectos geotérmicos en América del Sur: una propuesta metodológica (PDF) (in Spanish). CEPAL.

- Communication Ministry (25 July 2020). "Diputados aprueba financiamiento para construcción de Planta Geotérmica Laguna Colorada" (in Spanish).

- Cortecci, Gianni; Boschetti, Tiziano; Mussi, Mario; Lameli, Christian Herrera; Mucchino, Claudio; Barbieri, Maurizio (2005). "New chemical and original isotopic data on waters from El Tatio geothermal field, northern Chile". Geochemical Journal. 39 (6): 547–571. Bibcode:2005GeocJ..39..547C. doi:10.2343/geochemj.39.547.

- De Silva, Shanaka L.; Francis, Peter (1991). Volcanoes of the central Andes. Vol. 220. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Delgadillo, T. Z.; Puente, Héctor G. (1998). The Laguna Colorada (Bolivia) Project: A Reservoir Engineering Assessment (Report). Transactions-Geothermal Resources Council. pp. 257–262.

- Fernandez-Turiel, J.L.; Garcia-Valles, M.; Gimeno-Torrente, D.; Saavedra-Alonso, J.; Martinez-Manent, S. (October 2005). "The hot spring and geyser sinters of El Tatio, Northern Chile". Sedimentary Geology. 180 (3–4): 125–147. Bibcode:2005SedG..180..125F. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2005.07.005.

- Damir, Galaz-Mandakovic Fernández (2014). "Uyuni, capital turística de Bolivia. Aproximaciones antropológicas a un fenómeno visual posmoderno desbordante". Teoría y Praxis (in Spanish). 16: 147–173.

- Lagos, Magdalena Sofía; Muñoz, José Francisco; Suárez, Francisco Ignacio; Fuenzalida, María José; Yáñez-Morroni, Gonzalo; Sanzana, Pedro (29 June 2023). "Investigating the effects of channelization in the Silala River: A review of the implementation of a coupled MIKE -11 and MIKE-SHE modeling system". WIREs Water. 11. doi:10.1002/wat2.1673.

- Ministry of Hydrocarbons and Energies (April 2022). Informe de rendición pública de cuentas inicial 2022 (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish).

- Müller, Daniel; Walter, Thomas R.; Zimmer, Martin; Gonzalez, Gabriel (1 December 2022). "Distribution, structural and hydrological control of the hot springs and geysers of El Tatio, Chile, revealed by optical and thermal infrared drone surveying". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 432: 107696. Bibcode:2022JVGR..43207696M. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2022.107696. ISSN 0377-0273. S2CID 253033476.

- Ort, Michael H. (October 2009). Two new supereruptions in the Altiplano-Puna volcanic complex of the central Andes. 2009 Portland GSA Annual Meeting.

- Pereyra Quiroga, Bruno; Meneses Rioseco, Ernesto; Kapinos, Gerhard; Brasse, Heinrich (1 September 2023). "Three-dimensional magnetotelluric inversion for the characterization of the Sol de Mañana high-enthalpy geothermal field, Bolivia". Geothermics. 113: 102748. Bibcode:2023Geoth.11302748P. doi:10.1016/j.geothermics.2023.102748. ISSN 0375-6505. S2CID 259617984.

- Pritchard, M. E.; Henderson, S. T.; Jay, J. A.; Soler, V.; Krzesni, D. A.; Button, N. E.; Welch, M. D.; Semple, A. G.; Glass, B.; Sunagua, M.; Minaya, E.; Amigo, A.; Clavero, J. (1 June 2014). "Reconnaissance earthquake studies at nine volcanic areas of the central Andes with coincident satellite thermal and InSAR observations". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 280: 90–103. Bibcode:2014JVGR..280...90P. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2014.05.004. ISSN 0377-0273.

- Suaznabar, Paola Adriana Coca; Quiroga, Bruno Pereyra; Villarreal, José Ramón Pérez (2019). "Well Drilling in Sol de Mañana Geothermal Field – Laguna Colorada Geothermal Project" (PDF). GRC Transactions. 43.

- Sullcani, Pedro Rómulo Ramos (2015). Well Data Analysis and Volumetric Assessment of the Sol de Mañana Geothermal Field, Bolivia (PDF). National Energy Authority (Iceland) (Report). United Nations University.

- USGS (1992). Geology and mineral resources of the Altiplano and Cordillera Occidental, Bolivia (Report). doi:10.3133/b1975.