In celestial mechanics, the specific relative angular momentum (often denoted or ) of a body is the angular momentum of that body divided by its mass. In the case of two orbiting bodies it is the vector product of their relative position and relative linear momentum, divided by the mass of the body in question.

Specific relative angular momentum plays a pivotal role in the analysis of the two-body problem, as it remains constant for a given orbit under ideal conditions. "Specific" in this context indicates angular momentum per unit mass. The SI unit for specific relative angular momentum is square meter per second.

Definition

The specific relative angular momentum is defined as the cross product of the relative position vector and the relative velocity vector .

where is the angular momentum vector, defined as .

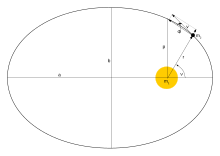

The vector is always perpendicular to the instantaneous osculating orbital plane, which coincides with the instantaneous perturbed orbit. It is not necessarily perpendicular to the average orbital plane over time.

Proof of constancy in the two body case

Under certain conditions, it can be proven that the specific angular momentum is constant. The conditions for this proof include:

- The mass of one object is much greater than the mass of the other one. ()

- The coordinate system is inertial.

- Each object can be treated as a spherically symmetrical point mass.

- No other forces act on the system other than the gravitational force that connects the two bodies.

Proof

The proof starts with the two body equation of motion, derived from Newton's law of universal gravitation:

where:

- is the position vector from to with scalar magnitude .

- is the second time derivative of . (the acceleration)

- is the Gravitational constant.

The cross product of the position vector with the equation of motion is:

Because the second term vanishes:

It can also be derived that:

Combining these two equations gives:

Since the time derivative is equal to zero, the quantity is constant. Using the velocity vector in place of the rate of change of position, and for the specific angular momentum: is constant.

This is different from the normal construction of momentum, , because it does not include the mass of the object in question.

Kepler's laws of planetary motion

Main article: Kepler's laws of planetary motionKepler's laws of planetary motion can be proved almost directly with the above relationships.

First law

The proof starts again with the equation of the two-body problem. This time the cross product is multiplied with the specific relative angular momentum

The left hand side is equal to the derivative because the angular momentum is constant.

After some steps (which includes using the vector triple product and defining the scalar to be the radial velocity, as opposed to the norm of the vector ) the right hand side becomes:

Setting these two expression equal and integrating over time leads to (with the constant of integration )

Now this equation is multiplied (dot product) with and rearranged

Finally one gets the orbit equation

which is the equation of a conic section in polar coordinates with semi-latus rectum and eccentricity .

Second law

The second law follows instantly from the second of the three equations to calculate the absolute value of the specific relative angular momentum.

If one connects this form of the equation with the relationship for the area of a sector with an infinitesimal small angle (triangle with one very small side), the equation

Third law

Kepler's third is a direct consequence of the second law. Integrating over one revolution gives the orbital period

for the area of an ellipse. Replacing the semi-minor axis with and the specific relative angular momentum with one gets

There is thus a relationship between the semi-major axis and the orbital period of a satellite that can be reduced to a constant of the central body.

See also

- Specific orbital energy, another conserved quantity in the two-body problem.

- Classical central-force problem § Specific angular momentum

References

| Gravitational orbits | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types |

| ||||||||

| Parameters |

| ||||||||

| Maneuvers | |||||||||

| Orbital mechanics |

| ||||||||

- ^ Vallado, David A. (2001). Fundamentals of astrodynamics and applications (2nd ed.). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 20–30. ISBN 0-7923-6903-3.

or

or  ) of a body is the

) of a body is the  and the relative

and the relative  .

.

is the angular momentum vector, defined as

is the angular momentum vector, defined as  .

.

and flight path angle

and flight path angle  of

of  in orbit around

in orbit around  . The most important measures of the

. The most important measures of the  ).

). )

)

.

. is the second time derivative of

is the second time derivative of  is the

is the

the second term vanishes:

the second term vanishes:

is constant. Using the velocity vector

is constant. Using the velocity vector  is constant.

is constant.

, because it does not include the mass of the object in question.

, because it does not include the mass of the object in question.

because the angular momentum is constant.

because the angular momentum is constant.

to be the radial velocity, as opposed to the norm of the vector

to be the radial velocity, as opposed to the norm of the vector  ) the right hand side becomes:

) the right hand side becomes:

)

)

and

and  .

.

with the relationship

with the relationship  for the area of a sector with an infinitesimal small angle

for the area of a sector with an infinitesimal small angle  (triangle with one very small side), the equation

(triangle with one very small side), the equation

of an ellipse. Replacing the semi-minor axis with

of an ellipse. Replacing the semi-minor axis with  and the specific relative angular momentum with

and the specific relative angular momentum with  one gets

one gets