Logo since 2017 Logo since 2017 | |

| Type | Computer-based standardized test |

|---|---|

| Administrator | College Board, Educational Testing Service |

| Skills tested | Writing, critical reading, mathematics |

| Purpose | Admission to undergraduate programs of universities or colleges |

| Year started | 1926; 99 years ago (1926) |

| Duration | 2 hours 14 minutes |

| Score range | Test scored on scale of 200–800, (in 10-point increments), on each of two sections (total 400–1600). Essay scored on scale of 2–8, in 1-point increments, on each of three criteria. |

| Offered | 7 times annually |

| Regions | Worldwide |

| Languages | English |

| Annual number of test takers | |

| Prerequisites | No official prerequisite. Intended for high school students. Fluency in English assumed. |

| Fee | US$60.00 to US$108.00, depending on country. |

| Used by | Most universities and colleges offering undergraduate programs in the U.S. |

| Website | sat |

The SAT (/ˌɛsˌeɪˈtiː/ ess-ay-TEE) is a standardized test widely used for college admissions in the United States. Since its debut in 1926, its name and scoring have changed several times. For much of its history, it was called the Scholastic Aptitude Test and had two components, Verbal and Mathematical, each of which was scored on a range from 200 to 800. Later it was called the Scholastic Assessment Test, then the SAT I: Reasoning Test, then the SAT Reasoning Test, then simply the SAT.

The SAT is wholly owned, developed, and published by the College Board and is administered by the Educational Testing Service. The test is intended to assess students' readiness for college. Historically, starting around 1937, the tests offered under the SAT banner also included optional subject-specific SAT Subject Tests, which were called SAT Achievement Tests until 1993 and then were called SAT II: Subject Tests until 2005; these were discontinued after June 2021. Originally designed not to be aligned with high school curricula, several adjustments were made for the version of the SAT introduced in 2016. College Board president David Coleman added that he wanted to make the test reflect more closely what students learn in high school with the new Common Core standards.

Many students prepare for the SAT using books, classes, online courses, and tutoring, which are offered by a variety of companies and organizations. One of the best known such companies is Kaplan, Inc., which has offered SAT preparation courses since 1946. Starting with the 2015–16 school year, the College Board began working with Khan Academy to provide free online SAT preparation courses. In the past, the test was taken using paper forms. Starting in March 2023 for international test-takers and March 2024 for those within the U.S., the testing is administered using a computer program called Bluebook. The test was also made adaptive, customizing the questions that are presented to the student based on how they perform on questions asked earlier in the test, and shortened from three hours to two hours and 14 minutes.

While a considerable amount of research has been done on the SAT, many questions and misconceptions remain. Outside of college admissions, the SAT is also used by researchers studying human intelligence in general and intellectual precociousness in particular, and by some employers in the recruitment process.

Function

U.S. states in blue had more seniors in the class of 2006 who took the SAT than the ACT while those in red had more seniors taking the ACT than the SAT.

U.S. states in blue had more seniors in the class of 2006 who took the SAT than the ACT while those in red had more seniors taking the ACT than the SAT. U.S. states in blue had more seniors in the class of 2022 who took the SAT than the ACT while those in red had more seniors taking the ACT than the SAT.

U.S. states in blue had more seniors in the class of 2022 who took the SAT than the ACT while those in red had more seniors taking the ACT than the SAT.

The SAT is typically taken by high school juniors and seniors. The College Board states that the SAT is intended to measure literacy, numeracy and writing skills that are needed for academic success in college. They state that the SAT assesses how well the test-takers analyze and solve problems—skills they learned in school that they will need in college.

The College Board also claims that the SAT, in combination with high school grade point average (GPA), provides a better indicator of success in college than high school grades alone, as measured by college freshman GPA. Various studies conducted over the lifetime of the SAT show a statistically significant increase in correlation of high school grades and college freshman grades when the SAT is factored in. The predictive validity and powers of the SAT are topics of research in psychometrics.

The SAT is a norm-referenced test intended to yield scores that follow a bell curve distribution among test-takers. To achieve this distribution, test designers include challenging multiple-choice questions with plausible but incorrect options, known as "distractors", exclude questions that a majority of students answer correctly, and impose tight time constraints during the examination.

There are substantial differences in funding, curricula, grading, and difficulty among U.S. secondary schools due to U.S. federalism, local control, and the prevalence of private, distance, and home schooled students. SAT (and ACT) scores are intended to supplement the secondary school record and help admission officers put local data—such as course work, grades, and class rank—in a national perspective.

Historically, the SAT was more widely used by students living in coastal states and the ACT was more widely used by students in the Midwest and South; in recent years, however, an increasing number of students on the East and West coasts have been taking the ACT. Since 2007, all four-year colleges and universities in the United States that require a test as part of an application for admission will accept either the SAT or ACT, and as of Fall 2022, more than 1400 four-year colleges and universities did not require any standardized test scores at all for admission, though some of them were planning to apply this policy only temporarily due to the coronavirus pandemic.

SAT test-takers are given two hours and 14 minutes to complete the test (plus a 10-minute break between the Reading and Writing section and the Math section), and as of 2024 the test costs US$60.00, plus additional fees for late test registration, registration by phone, registration changes, rapid delivery of results, delivery of results to more than four institutions, result deliveries ordered more than nine days after the test, and testing administered outside the United States, as applicable, and fee waivers are offered to low-income students within the U.S. and its territories. Scores on the SAT range from 400 to 1600, combining test results from two 200-to-800-point sections: the Mathematics section and the Evidence-Based Reading and Writing section. Although taking the SAT, or its competitor the ACT, is required for freshman entry to many colleges and universities in the United States, during the late 2010s, many institutions made these entrance exams optional, but this did not stop the students from attempting to achieve high scores as they and their parents are skeptical of what "optional" means in this context. In fact, the test-taking population was increasing steadily. And while this may have resulted in a long-term decline in scores, experts cautioned against using this to gauge the scholastic levels of the entire U.S. population.

Structure

The SAT has two main sections, namely Evidence-Based Reading and Writing (EBRW, normally known as the "English" portion of the test) and the Math section. These are both further broken down into four sections: Reading, Writing and Language, Math (no calculator), and Math (calculator allowed). Until the summer of 2021, the test taker was also optionally able to write an essay which, in that case, is the fifth test section. (The essay was dropped after June 2021, except in a few states and school districts.) The total time for the scored portion of the SAT is two hours and 14 minutes. Some test takers who are not taking the essay may also have a fifth section, which is used, at least in part, for the pretesting of questions that may appear on future administrations of the SAT. (These questions are not included in the computation of the SAT score.)

Two section scores result from taking the SAT: Evidence-Based Reading and Writing, and Math. Section scores are reported on a scale of 200 to 800, and each section score is a multiple of ten. A total score for the SAT is calculated by adding the two section scores, resulting in total scores that range from 400 to 1600. In addition to the two section scores, three "test" scores on a scale of 10 to 40 are reported, one for each of Reading, Writing and Language, and Math, with increment of 1 for Reading / Writing and Language, and 0.5 for Math. There are also two cross-test scores that each range from 10 to 40 points: Analysis in History/Social Studies and Analysis in Science. The essay, if taken, was scored separately from the two section scores. Two people score each essay by each awarding 1 to 4 points in each of three categories: Reading, Analysis, and Writing. These two scores from the different examiners are then combined to give a total score from 2 to 8 points per category. Though sometimes people quote their essay score out of 24, the College Board themselves do not combine the different categories to give one essay score, instead giving a score for each category.

There is no penalty or negative marking for guessing on the SAT: scores are based on the number of questions answered correctly. The optional essay was last featured in the June 2021 administration. College Board said it discontinued the essay section because "there are other ways for students to demonstrate their mastery of essay writing," including the test's reading and writing portion. It also acknowledged that the COVID-19 pandemic had played a role in the change, accelerating 'a process already underway'.

Reading Test

The Reading Test of the SAT contains one section of 52 questions and a time limit of 65 minutes. All questions are multiple-choice and based on reading passages. Tables, graphs, and charts may accompany some passages, but no math is required to correctly answer the corresponding questions. There are five passages (up to two of which may be a pair of smaller passages) on the Reading Test and ten or eleven questions per passage or passage pair. SAT Reading passages draw from three main fields: history, social studies, and science. Each SAT Reading Test always includes: one passage from U.S. or world literature; one passage from either a U.S. founding document or a related text; one passage about economics, psychology, sociology, or another social science; and, two science passages. Answers to all of the questions are based only on the content stated in or implied by the passage or passage pair.

The Reading Test contributes (with the Writing and Language Test) to two subscores, each ranging from 1 to 15 points:

- Command of Evidence

- Words in Context

Writing and Language Test

The Writing and Language Test of the SAT is made up of one section with 44 multiple-choice questions and a time limit of 35 minutes. As with the Reading Test, all questions are based on reading passages which may be accompanied by tables, graphs, and charts. The test taker will be asked to read the passages and suggest corrections or improvements for the contents underlined. Reading passages on this test range in content from topic arguments to nonfiction narratives in a variety of subjects. The skills being evaluated include: increasing the clarity of argument; improving word choice; improving analysis of topics in social studies and science; changing sentence or word structure to increase organizational quality and impact of writing; and, fixing or improving sentence structure, word usage, and punctuation.

The Writing and Language Test reports two subscores, each ranging from 1 to 15 points:

- Expression of Ideas

- Standard English Conventions

Mathematics

The mathematics portion of the SAT is divided into two sections: Math Test – No Calculator and Math Test – Calculator. In total, the SAT math test is 80 minutes long and includes 58 questions: 45 multiple choice questions and 13 grid-in questions. The multiple choice questions have four possible answers; the grid-in questions are free response and require the test taker to provide an answer.

- The Math Test – No Calculator section has 20 questions (15 multiple choice and 5 grid-in) and lasts 25 minutes.

- The Math Test – Calculator section has 38 questions (30 multiple choice and 8 grid-in) and lasts 55 minutes.

Several scores are provided to the test taker for the math test. A subscore (on a scale of 1 to 15) is reported for each of three categories of math content:

- "Heart of Algebra" (linear equations, systems of linear equations, and linear functions)

- "Problem Solving and Data Analysis" (statistics, modeling, and problem-solving skills)

- "Passport to Advanced Math" (non-linear expressions, radicals, exponentials and other topics that form the basis of more advanced math).

A test score for the math test is reported on a scale of 10 to 40, with an increment of 0.5, and a section score (equal to the test score multiplied by 20) is reported on a scale of 200 to 800.

Calculator use

All scientific and most graphing calculators, including computer algebra system (CAS) calculators, are permitted on the SAT Math – Calculator section only. However, with the change to the Digital SAT during 2023 and 2024, a graphing calculator may be used throughout the entire test and is accessible through the test application program. All four-function calculators are allowed as well; however, these devices are not recommended. Mobile phone and smartphone calculators, calculators with typewriter-like (QWERTY) keyboards, laptops and other portable computers, and calculators capable of accessing the Internet are not permitted.

Research was conducted by the College Board to study the effect of calculator use on SAT I: Reasoning Test math scores. The study found that performance on the math section was associated with the extent of calculator use: those using calculators on about one third to one half of the items averaged higher scores than those using calculators more or less frequently. However, the effect was "more likely to have been the result of able students using calculators differently than less able students rather than calculator use per se." There is some evidence that the frequent use of a calculator in school outside of the testing situation has a positive effect on test performance compared to those who do not use calculators in school.

Style of questions

Most of the questions on the SAT, except for the grid-in math responses, are multiple choice; all multiple-choice questions have four answer choices, one of which is correct. Thirteen of the questions on the math portion of the SAT (about 22% of all the math questions) are not multiple choice. They instead require the test taker to bubble in a number in a four-column grid.

All questions on each section of the SAT are weighted equally. For each correct answer, one raw point is added. No points are deducted for incorrect answers. The final score is derived from the raw score; the precise conversion chart varies between test administrations.

| Section | Average score 2024 (200–800) | Time (minutes) | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematics | 505 | 25 + 55 = 80 | Number and operations; algebra and functions; geometry; statistics, probability, and data analysis |

| Evidence-Based Reading and Writing | 519 | 65 + 35 = 100 | Vocabulary, Critical reading, sentence-level reading, Grammar, usage, and diction |

Logistics

Frequency

The SAT is offered seven times a year in the United States: in August, October, November, December, March, May, and June. For international students SAT is offered four times a year: in October, December, March and May (2020 exception: To cover worldwide May cancelation, an additional September exam was introduced, and August was made available to international test-takers as well). The test is typically offered on the first Saturday of the month for the October, November, December, May, and June administrations. The test was taken by 1,973,891 high school graduates in the class of 2024.

Candidates wishing to take the test may register online at the College Board's website or by mail at least three weeks before the test date.

Fees

As of 2022, the SAT costs US$60.00, plus additional fees if testing outside the United States. The College Board makes fee waivers available for low-income students. Additional fees apply for late registration, standby testing, registration changes, scores by telephone, and extra score reports (beyond the four provided for free).

Accommodation for candidates with disabilities

Students with verifiable disabilities, including physical and learning disabilities, are eligible to take the SAT with accommodations. The standard time increase for students requiring additional time due to learning disabilities or physical handicaps is time + 50%; time + 100% is also offered.

Change from paper-based to digital

In January 2022, College Board announced that the SAT would change from paper-based to digital (computer-based). International (non-U.S.) testing centers began using the digital format on March 11, 2023. The December 2023 SAT was the last SAT test offered on paper. The switch to the digital format occurred on March 9, 2024, in the U.S. The digital SAT takes about an hour less to do than the paper-based test (two hours vs. three). It is administered in an official test center, as before, but the students use their own testing devices (a portable computer or tablet). If a student cannot bring his or her own device, one can be requested from College Board. Before the test, College Board's "Bluebook" app must have been successfully installed on the testing device.

The new test is adaptive, meaning that students have two modules per section (reading/writing and math), with the second module being adaptive to the demonstrated level based on the results from the first module. On the reading and writing sections, the questions will have shorter passages for each question. On the math sections, the word problems will be more concise. Students have a ten-minute break after the first two English modules and before the two math modules. A timer is built into the testing software and will automatically begin once the student finishes the second English module. New tools such as a question flagger, a timer, and an integrated graphing calculator are included in the new test as well.

Scaled scores and percentiles

Students receive their online score reports approximately two to three weeks after test administration (longer for mailed, paper scores). Included in the report is the total score (the sum of the two section scores, with each section graded on a scale of 200–800) and three subscores (in reading, writing, and analysis, each on a scale of 2–8) for the optional essay. Students may also receive, for an additional fee, various score verification services, including (for select test administrations) the Question and Answer Service, which provides the test questions, the student's answers, the correct answers, and the type and difficulty of each question.

In addition, students receive two percentile scores, each of which is defined by the College Board as the percentage of students in a comparison group with equal or lower test scores. One of the percentiles, called the "Nationally Representative Sample Percentile", uses as a comparison group all 11th and 12th graders in the United States, regardless of whether or not they took the SAT. This percentile is theoretical and is derived using methods of statistical inference. The second percentile, called the "SAT User Percentile", uses actual scores from a comparison group of recent United States students that took the SAT. For example, for the school year 2019–2020, the SAT User Percentile was based on the test scores of students in the graduating classes of 2018 and 2019 who took the SAT (specifically, the 2016 revision) during high school. Students receive both types of percentiles for their total score as well as their section scores.

Percentiles for total scores (2022)

| Score, 400–1600 scale | SAT User | Nationally representative sample |

|---|---|---|

| 1600 | 99+ | 99+ |

| 1550 | 99 | 99+ |

| 1500 | 98 | 99 |

| 1450 | 96 | 99 |

| 1400 | 93 | 97 |

| 1350 | 90 | 94 |

| 1300 | 86 | 91 |

| 1250 | 81 | 86 |

| 1200 | 75 | 81 |

| 1150 | 68 | 74 |

| 1100 | 60 | 67 |

| 1050 | 51 | 58 |

| 1000 | 43 | 48 |

| 950 | 35 | 38 |

| 900 | 27 | 29 |

| 850 | 19 | 21 |

| 800 | 13 | 14 |

| 750 | 7 | 8 |

| 700 | 3 | 4 |

| 650 | 1 | 1 |

| 640–400 | 1- | 1- |

Percentiles for total scores (2006)

The following chart summarizes the original percentiles used for the version of the SAT administered in March 2005 through January 2016. These percentiles used students in the graduating class of 2006 as the comparison group.

| Percentile | Score 400–1600 scale, (official, 2006) |

Score, 600–2400 scale (official, 2006) |

|---|---|---|

| 99.93/99.98* | 1600 | 2400 |

| 99.5 | ≥1540 | ≥2280 |

| 99 | ≥1480 | ≥2200 |

| 98 | ≥1450 | ≥2140 |

| 97 | ≥1420 | ≥2100 |

| 93 | ≥1340 | ≥1990 |

| 88 | ≥1280 | ≥1900 |

| 81 | ≥1220 | ≥1800 |

| 72 | ≥1150 | ≥1700 |

| 61 | ≥1090 | ≥1600 |

| 48 | ≥1010 | ≥1500 |

| 36 | ≥950 | ≥1400 |

| 24 | ≥870 | ≥1300 |

| 15 | ≥810 | ≥1200 |

| 8 | ≥730 | ≥1090 |

| 4 | ≥650 | ≥990 |

| 2 | ≥590 | ≥890 |

| * The percentile of the perfect score was 99.98 on the 2400 scale and 99.93 on the 1600 scale. | ||

Percentiles for total scores (1984)

| Score (1984) | Percentile |

|---|---|

| 1600 | 99.9995 |

| 1550 | 99.983 |

| 1500 | 99.89 |

| 1450 | 99.64 |

| 1400 | 99.10 |

| 1350 | 98.14 |

| 1300 | 96.55 |

| 1250 | 94.28 |

| 1200 | 91.05 |

| 1150 | 86.93 |

| 1100 | 81.62 |

| 1050 | 75.31 |

| 1000 | 67.81 |

| 950 | 59.64 |

| 900 | 50.88 |

| 850 | 41.98 |

| 800 | 33.34 |

| 750 | 25.35 |

| 700 | 18.26 |

| 650 | 12.37 |

| 600 | 7.58 |

| 550 | 3.97 |

| 500 | 1.53 |

| 450 | 0.29 |

| 400 | 0.002 |

Percentiles for verbal and math scores (1969–70)

| Score, 200–800 scale |

Verbal SAT User | Verbal, nationally representative sample |

Math SAT User, Boys |

Math SAT User, Girls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 800 | 99+ | 99+ | 99+ | 99+ |

| 750 | 99+ | 99+ | 99 | 99+ |

| 700 | 98 | 99+ | 95 | 99 |

| 650 | 95 | 98 | 89 | 96 |

| 600 | 89 | 95 | 78 | 89 |

| 550 | 79 | 90 | 65 | 79 |

| 500 | 66 | 82 | 48 | 63 |

| 450 | 50 | 72 | 33 | 46 |

| 400 | 33 | 58 | 20 | 29 |

| 350 | 18 | 44 | 11 | 16 |

| 300 | 7 | 28 | 4 | 6 |

| 250 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| 200 | 1− | 4 | 1− | 1− |

The mean verbal score was 461 for students taking the SAT, 383 for the sample of all students.

The mathematical scores for 1969–70 were broken out by gender rather than reported as a whole; the mean math score for boys was 415, for girls 378. The differences for the nationally sampled population for math (not shown in table) were similar to those for the verbal section.

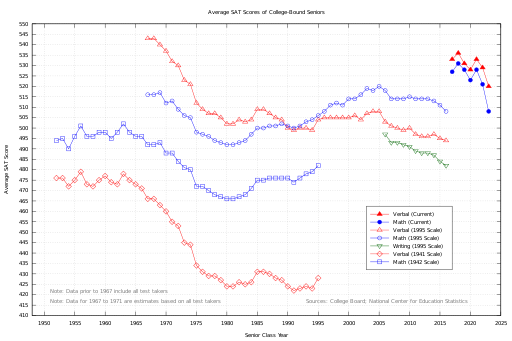

Ceilings and trends

The version of the SAT administered before April 1995 had a very high ceiling. For example, in the 1985–1986 school year, only 9 students out of 1.7 million test takers obtained a score of 1600.

In 2015 the average score for the Class of 2015 was 1490 out of a maximum 2400. That was down 7 points from the previous class's mark and was the lowest composite score of the past decade.

SAT–ACT score comparisons

The College Board and ACT, Inc., conducted a joint study of students who took both the SAT and the ACT between September 2004 (for the ACT) or March 2005 (for the SAT) and June 2006. Tables were provided to concord scores for students taking the SAT after January 2005 and before March 2016. In May 2016, the College Board released concordance tables to concord scores on the SAT used from March 2005 through January 2016 to the SAT used since March 2016, as well as tables to concord scores on the SAT used since March 2016 to the ACT.

In 2018, the College Board, in partnership with the ACT, introduced a new concordance table to better compare how a student would fare one test to another. This is now considered the official concordance to be used by college professionals and is replacing the one from 2016. The new concordance no longer features the old SAT (out of 2,400), just the new SAT (out of 1,600) and the ACT (out of 36).

As of 2018, the most appropriate corresponding SAT score point for the given ACT score is also shown in the table below.

| ACT Composite Score | SAT Total Score Range | SAT Total Score |

|---|---|---|

| 36 | 1570–1600 | 1590 |

| 35 | 1530–1560 | 1540 |

| 34 | 1490–1520 | 1500 |

| 33 | 1450–1480 | 1460 |

| 32 | 1420–1440 | 1430 |

| 31 | 1390–1410 | 1400 |

| 30 | 1360–1380 | 1370 |

| 29 | 1330–1350 | 1340 |

| 28 | 1300–1320 | 1310 |

| 27 | 1260–1290 | 1280 |

| 26 | 1230–1250 | 1240 |

| 25 | 1200–1220 | 1210 |

| 24 | 1160–1190 | 1180 |

| 23 | 1130–1150 | 1140 |

| 22 | 1100–1120 | 1110 |

| 21 | 1060–1090 | 1080 |

| 20 | 1030–1050 | 1040 |

| 19 | 990–1020 | 1010 |

| 18 | 960–980 | 970 |

| 17 | 920–950 | 930 |

| 16 | 880–910 | 890 |

| 15 | 830–870 | 850 |

| 14 | 780–820 | 800 |

| 13 | 730–770 | 760 |

| 12 | 690–720 | 710 |

| 11 | 650–680 | 670 |

| 10 | 620–640 | 630 |

| 9 | 590–610 | 590 |

Elucidation

Preparation

Pioneered by Stanley Kaplan in 1946 with a 64-hour course, SAT preparation has become a highly lucrative field. Many companies and organizations offer test preparation in the form of books, classes, online courses, and tutoring. The test preparation industry began almost simultaneously with the introduction of university entrance exams in the U.S. and flourished from the start. Test-preparation scams are a genuine problem for parents and students. In general, East Asian Americans, especially Korean Americans, are the most likely to take private SAT preparation courses while African Americans typically rely more one-on-one tutoring for remedial learning.

Nevertheless, the College Board maintains that the SAT is essentially uncoachable and research by the College Board and the National Association of College Admission Counseling suggests that tutoring courses result in an average increase of about 20 points on the math section and 10 points on the verbal section. Indeed, researchers have shown time and again that preparation courses tend to offer at best a modest boost to test scores. Like IQ scores, which are a strong correlate, SAT scores tend to be stable over time, meaning SAT preparation courses offer only a limited advantage. An early meta-analysis (from 1983) found similar results and noted "the size of the coaching effect estimated from the matched or randomized studies (10 points) seems too small to be practically important." Statisticians Ben Domingue and Derek C. Briggs examined data from the Education Longitudinal Survey of 2002 and found that the effects of coaching were only statistically significant for mathematics; moreover, coaching had a greater effect on certain students than others, especially those who have taken rigorous courses and those of high socioeconomic status. A 2012 systematic literature review estimated a coaching effect of 23 and 32 points for the math and verbal tests, respectively. A 2016 meta-analysis estimated the effect size to be 0.09 and 0.16 for the verbal and math sections respectively, although there was a large degree of heterogeneity. Meanwhile, a 2011 study found that the effects of one-on-one tutoring to be minimal among all ethnic groups. Public misunderstanding of how to prepare for the SAT continues to be exploited by the preparation industry.

While there is a link between family background and taking an SAT preparation course, not all students benefit equally from such an investment. In fact, any average gains in SAT scores due to such courses are primarily due to improvements among East Asian Americans. When this group is broken down even further, Korean Americans are more likely to take SAT prep courses than Chinese Americans, taking full advantage of their Church communities and ethnic economy.

The College Board announced a partnership with the non-profit organization Khan Academy to offer free test-preparation materials starting in the 2015–16 academic year to help level the playing field for students from low-income families. Students may also bypass costly preparation programs using the more affordable official guide from the College Board and with solid studying habits.

The College Board also offers a test called the Preliminary SAT/National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test (PSAT/NMSQT), and there is some evidence that taking the PSAT at least once can help students do better on the SAT; moreover, like the case for the SAT, top scorers on the PSAT could earn scholarships. According to cognitive scientist Sian Beilock, 'choking', or substandard performance on important occasions, such as taking the SAT, can be prevented by doing plenty of practice questions and proctored exams to improve procedural memory, making use of the booklet to write down intermediate steps to avoid overloading working memory, and writing a diary entry about one's anxieties on the day of the exam to enhance self-empathy and positive self-image. Sleep hygiene is important as the quality of sleep during the days leading to the exam can improve performance. Moreover, it has been shown that later class times (8:30 am rather than 7:30am), which better suits the shifted circadian rhythm of teenagers, can raise SAT scores enough to change the tier of the colleges and universities student might be admitted to.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, a large number of American colleges and universities decided to make standardized test scores optional for prospective students. Nevertheless, many students still chose to take the SAT and to enroll in preparation programs, which continued to be profitable.

Predictive validity and powers

In 2009, education researchers Richard C. Atkinson and Saul Geiser from the University of California (UC) system argued that high school GPA is better than the SAT at predicting college grades regardless of high school type or quality. In its 2020 report, the UC academic senate found that the SAT was better than high school GPA at predicting first year GPA, and just as good as high school GPA at predicting undergraduate GPA, first year retention, and graduation. This predictive validity was found to hold across demographic groups, with the report noting that standardized test scores were actually "better predictors of success for students who are Underrepresented Minority students (URMs), who are first-generation, or whose families are low-income." A series of College Board reports point to similar predictive validity across demographic groups.

But a month after the UC academic senate report, Saul Geiser disputed the UC academic senate's findings, saying "that the Senate claims are 'spurious', based on a fundamental error of omitting student demographics in the prediction model". Indicating when high school GPA is combined with demographics in the prediction, the SAT is less reliable. Li Cai, a UCLA professor who directs the National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing, indicated that the UC Academic Senate did include student demographics by using a different and simpler model for the public to understand and that the discriminatory impacts of the SAT are compensated during the admissions process. Jesse Rothstein, a UC Berkeley professor of public policy and economics, countered Li's claim, mentioning that the UC academic senate "got a lot of things wrong about the SAT", overstates the value of the SAT, and "no basis for its conclusion that UC admissions 'compensate' for test score gaps between groups." However, by analyzing their own institutional data, Brown, Yale, and Dartmouth universities reached the conclusion that SAT scores are more reliable predictors of collegiate success than GPA. Furthermore, the scores allow them to identify more potentially qualified students from disadvantaged backgrounds than they otherwise would. At the University of Texas at Austin, students who declined to submit SAT scores when such scores were optional performed more poorly than their peers who did. These results were replicated by a study conducted by the non-profit organization Opportunity Insights analyzing data from Ivy League institutions (Brown University, Columbia University, Cornell University, Dartmouth College, Harvard University, Princeton University, the University of Pennsylvania, and Yale University) plus Stanford University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the University of Chicago. A 2009 study found that SAT or ACT scores along with high-school GPAs are strong predictors of cumulative university GPAs. In particular, those with standardized test scores in the 50th percentile or better had a two-thirds chance of having a cumulative university GPA in the top half. A 2010 meta-analysis by researchers from the University of Minnesota offered evidence that standardized admissions tests such as the SAT predicted not only freshman GPA but also overall collegiate GPA. A 2012 study from the same university using a multi-institutional data set revealed that even after controlling for socioeconomic status and high-school GPA, SAT scores were still as capable of predicting freshman GPA among university or college students. A 2019 study with a sample size of around a quarter of a million students suggests that together, SAT scores and high-school GPA offer an excellent predictor of freshman collegiate GPA and second-year retention. In 2018, psychologists Oren R. Shewach, Kyle D. McNeal, Nathan R. Kuncel, and Paul R. Sackett showed that both high-school GPA and SAT scores predict enrollment in advanced collegiate courses, even after controlling for Advanced Placement credits.

Education economist Jesse M. Rothstein indicated in 2005 that high-school average SAT scores were better at predicting freshman university GPAs compared to individual SAT scores. In other words, a student's SAT scores were not as informative with regards to future academic success as his or her high school's average. In contrast, individual high-school GPAs were a better predictor of collegiate success than average high-school GPAs. Furthermore, an admissions officer who failed to take average SAT scores into account would risk overestimating the future performance of a student from a low-scoring school and underestimating that of a student from a high-scoring school.

While the SAT is correlated with intelligence and as such estimates individual differences, it does not have anything to say about "effective cognitive performance" or what intelligent people do. Nor does it measure non-cognitive traits associated with academic success such as positive attitudes or conscientiousness. Psychometricians Thomas R. Coyle and David R. Pillow showed in 2008 that the SAT predicts college GPA even after removing the general factor of intelligence (g), with which it is highly correlated.

Like other standardized tests such as the ACT or the GRE, the SAT is a traditional method for assessing the academic aptitude of students who have had vastly different educational experiences and as such is focused on the common materials that the students could reasonably be expected to have encountered throughout the course of study. As such the mathematics section contains no materials above the precalculus level, for instance. Psychologist Raymond Cattell referred to this as testing for "historical" rather than "current" crystallized intelligence. Psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman further noted that the SAT can only measure a snapshot of a person's performance at a particular moment in time. Educational psychologists Jonathan Wai, David Lubinski, and Camilla Benbow observed that one way to increase the predictive validity of the SAT is by assessing the student's spatial reasoning ability, as the SAT at present does not contain any questions to that effect. Spatial reasoning skills are important for success in STEM. A 2006 study led by psychometrician Robert Sternberg found that the ability of SAT scores and high-school GPAs to predict collegiate performance could further be enhanced by additional assessments of analytical, creative, and practical thinking.

Experimental psychologist Meredith Frey noted that while advances in education research and neuroscience can help incrementally improve the ability to predict scholastic achievement in the future, the SAT or other standardized tests likely will remain a valuable tool to build upon. In a 2014 op-ed for The New York Times, psychologist John D. Mayer called the predictive powers of the SAT "an astonishing achievement" and cautioned against making it and other standardized tests optional. Research by psychometricians David Lubinsky, Camilla Benbow, and their colleagues has shown that the SAT could even predict life outcomes beyond university.

Difficulty and relative weight

The SAT rigorously assesses students' mental stamina, memory, speed, accuracy, and capacity for abstract and analytical reasoning. For American universities and colleges, standardized test scores are the most important factor in admissions, second only to high-school GPAs. By international standards, however, the SAT is not that difficult. For example, South Korea's College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT) and Finland's Matriculation Examination are both longer, tougher, and count for more towards the admissibility of a student to university. In many countries around the world, exams, including university entrance exams, are the sole deciding factor of admission; school grades are simply irrelevant. In China and India, doing well on the Gaokao or the IIT-JEE, respectively, enhances the social status of the students and their families.

In an article from 2012, educational psychologist Jonathan Wai argued that the SAT was too easy to be useful to the most competitive of colleges and universities, whose applicants typically had brilliant high-school GPAs and standardized test scores. Admissions officers therefore had the burden of differentiating the top scorers from one another, not knowing whether or not the students' perfect or near-perfect scores truly reflected their scholastic aptitudes. He suggested that the College Board make the SAT more difficult, which would raise the measurement ceiling of the test, allowing the top schools to identify the best and brightest among the applicants. At that time, the College Board was already working on making the SAT tougher. The changes were announced in 2014 and implemented in 2016.

After realizing the June 2018 test was easier than usual, the College Board made adjustments resulting in lower-than-expected scores, prompting complaints from the students, though some understood this was to ensure fairness. In its analysis of the incident, the Princeton Review supported the idea of curving grades, but pointed out that the test was incapable of distinguishing students in the 86th percentile (650 points) or higher in mathematics. The Princeton Review also noted that this particular curve was unusual in that it offered no cushion against careless or last-minute mistakes for high-achieving students. The Review posted a similar blog post for the SAT of August 2019, when a similar incident happened and the College Board responded in the same manner, noting, "A student who misses two questions on an easier test should not get as good a score as a student who misses two questions on a hard test. Equating takes care of that issue." It also cautioned students against retaking the SAT immediately, for they might be disappointed again, and recommended that instead, they give themselves some "leeway" before trying again.

Recognition

The College Board claims that outside of the United States, the SAT is considered for university admissions in approximately 70 countries, as of the 2023–24 academic year.

Association with general cognitive ability

In a 2000 study, psychometrician Ann M. Gallagher and her colleagues found that only the top students made use of intuitive reasoning in solving problems encountered on the mathematics section of the SAT. Cognitive psychologists Brenda Hannon and Mary McNaughton-Cassill discovered that having a good working memory, the ability of knowledge integration, and low levels of test anxiety predicts high performance on the SAT.

Frey and Detterman (2004) investigated associations of SAT scores with intelligence test scores. Using an estimate of general mental ability, or g, based on the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery, they found SAT scores to be highly correlated with g (r=.82 in their sample, .857 when adjusted for non-linearity) in their sample taken from a 1979 national probability survey. Additionally, they investigated the correlation between SAT results, using the revised and recentered form of the test, and scores on the Raven's Advanced Progressive Matrices, a test of fluid intelligence (reasoning), this time using a non-random sample. They found that the correlation of SAT results with scores on the Raven's Advanced Progressive Matrices was .483, they estimated that this correlation would have been about 0.72 were it not for the restriction of ability range in the sample. They also noted that there appeared to be a ceiling effect on the Raven's scores which may have suppressed the correlation. Beaujean and colleagues (2006) have reached similar conclusions to those reached by Frey and Detterman. Because the SAT is strongly correlated with general intelligence, it can be used as a proxy to measure intelligence, especially when the time-consuming traditional methods of assessment are unavailable.

Psychometrician Linda Gottfredson noted that the SAT is effective at identifying intellectually gifted college-bound students.

For decades many critics have accused designers of the verbal SAT of cultural bias as an explanation for the disparity in scores between poorer and wealthier test-takers, with the biggest critics coming from the University of California system. A famous example of this perceived bias in the SAT I was the oarsman–regatta analogy question, which is no longer part of the exam. The object of the question was to find the pair of terms that had the relationship most similar to the relationship between "runner" and "marathon". The correct answer was "oarsman" and "regatta". The choice of the correct answer was thought to have presupposed students' familiarity with rowing, a sport popular with the wealthy. However, for psychometricians, analogy questions are a useful tool to gauge the mental abilities of students, for, even if the meaning of two words are unclear, a student with sufficiently strong analytical thinking skills should still be able to identify their relationships. Analogy questions were removed in 2005. In their place are questions that provide more contextual information should the students be ignorant of the relevant definition of a word, making it easier for them to guess the correct answer.

Association with college or university majors and rankings

In 2010, physicists Stephen Hsu and James Schombert of the University of Oregon examined five years of student records at their school and discovered that the academic standing of students majoring in mathematics or physics (but not biology, English, sociology, or history) was strongly dependent on SAT mathematics scores. Students with SAT mathematics scores below 600 were highly unlikely to excel as a mathematics or physics major. Nevertheless, they found no such patterns between the SAT verbal, or combined SAT verbal and mathematics and the other aforementioned subjects.

In 2015, educational psychologist Jonathan Wai of Duke University analyzed average test scores from the Army General Classification Test in 1946 (10,000 students), the Selective Service College Qualification Test in 1952 (38,420), Project Talent in the early 1970s (400,000), the Graduate Record Examination between 2002 and 2005 (over 1.2 million), and the SAT Math and Verbal in 2014 (1.6 million). Wai identified one consistent pattern: those with the highest test scores tended to pick the physical sciences and engineering as their majors while those with the lowest were more likely to choose education and agriculture. (See figure below.)

A 2020 paper by Laura H. Gunn and her colleagues examining data from 1389 institutions across the United States unveiled strong positive correlations between the average SAT percentiles of incoming students and the shares of graduates majoring in STEM and the social sciences. On the other hand, they found negative correlations between the former and the shares of graduates in psychology, theology, law enforcement, recreation and fitness.

Various researchers have established that average SAT or ACT scores and college ranking in the U.S. News & World Report are highly correlated, almost 0.9. Between the 1980s and the 2010s, the U.S. population grew while universities and colleges did not expand their capacities as substantially. As a result, admissions rates fell considerably, meaning it has become more difficult to get admitted to a school whose alumni include one's parents. On top of that, high-scoring students nowadays are much more likely to leave their hometowns in pursuit of higher education at prestigious institutions. Consequently, standardized tests, such as the SAT, are a more reliable measure of selectivity than admissions rates. Still, when Michael J. Petrilli and Pedro Enamorado analyzed the SAT composite scores (math and verbal) of incoming freshman classes of 1985 and 2016 of the top universities and liberal arts colleges in the United States, they found that the median scores of new students increased by 93 points for their sample, from 1216 to 1309. In particular, fourteen institutions saw an increase of at least 150 points, including the University of Notre-Dame (from 1290 to 1440, or 150 points) and Elon College (from 952 to 1192, or 240 points).

Association with types of schooling

While there seems to be evidence that private schools tend to produce students who do better on standardized tests such as the ACT or the SAT, Keven Duncan and Jonathan Sandy showed, using data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Youth, that when student characteristics, such as age, race, and sex (7%), family background (45%), school quality (26%), and other factors were taken into account, the advantage of private schools diminished by 78%. The researchers concluded that students attending private schools already had the attributes associated with high scores on their own.

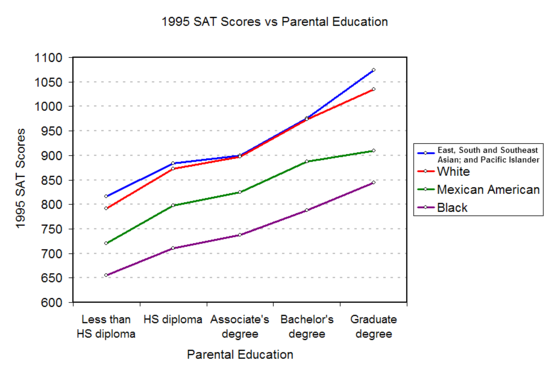

Association with educational and societal standings and outcomes

Research from the University of California system published in 2001 analyzing data of their undergraduates between Fall 1996 through Fall 1999, inclusive, found that the SAT II was the single best predictor of collegiate success in the sense of freshman GPA, followed by high-school GPA, and finally the SAT I. After controlling for family income and parental education, the already low ability of the SAT to measure aptitude and college readiness fell sharply while the more substantial aptitude and college readiness measuring abilities of high school GPA and the SAT II each remained undiminished (and even slightly increased). The University of California system required both the SAT I and the SAT II from applicants to the UC system during the four academic years of the study. This analysis is heavily publicized but is contradicted by many studies.

There is evidence that the SAT is correlated with societal and educational outcomes, including finishing a four-year university program. A 2012 paper from psychologists at the University of Minnesota analyzing multi-institutional data sets suggested that the SAT maintained its ability to predict collegiate performance even after controlling for socioeconomic status (as measured by the combination of parental educational attainment and income) and high-school GPA. This means that SAT scores were not merely a proxy for measuring socioeconomic status, the researchers concluded. This finding has been replicated and shown to hold across racial or ethnic groups and for both sexes. Moreover, the Minnesota researchers found that the socioeconomic status distributions of the student bodies of the schools examined reflected those of their respective applicant pools. Because of what it measures, a person's SAT scores cannot be separated from their socioeconomic background. However, the correlation between SAT scores and parental income or socioeconomic status should not be taken to mean causation. It could be that high scorers have intelligent parents who work cognitively demanding jobs and as such earn higher salaries. In addition, the correlation is only significant between biological families, not adoptive ones, suggesting that this might be due to genetic heritage, not economic wealth.

In 2007, Rebecca Zwick and Jennifer Greif Green observed that a typical analysis did not take into account that heterogeneity of the high schools attended by the students in terms of not just the socioeconomic statuses of the student bodies but also the standards of grading. Zwick and Greif Green proceeded to show that when these were accounted for, the correlation between family socioeconomic status and classroom grades and rank increased whereas that between socioeconomic status and SAT scores fell. They concluded that school grades and SAT scores were similarly associated with family income.

According to the College Board, in 2019, 56% of the test takers had parents with a university degree, 27% parents with no more than a high-school diploma, and about 9% who did not graduate from high school. (8% did not respond to the question.)

Association with family structures

One of the proposed partial explanations for the gap between Asian- and European-American students in educational achievement, as measured for example by the SAT, is the general tendency of Asians to come from stable two-parent households. In their 2018 analysis of data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, economists Adam Blandin, Christopher Herrington, and Aaron Steelman concluded that family structure played an important role in determining educational outcomes in general and SAT scores in particular. Families with only one parent who has no degrees were designated 1L, with two parents but no degrees 2L, and two parents with at least one degree between them 2H. Children from 2H families held a significant advantage of those from 1L families, and this gap grew between 1990 and 2010. Because the median SAT composite scores (verbal and mathematics) for 2H families grew by 20 points while those of 1L families fell by one point, the gap between them increased by 21 points, or a fifth of one standard deviation.

Sex differences

In performance

In 2013, the American College Testing Board released a report stating that boys outperformed girls on the mathematics section of the test, a significant gap that has persisted for over 35 years. As of 2015, boys on average earned 32 points more than girls on the SAT mathematics section. Among those scoring in the 700–800 range, the male-to-female ratio was 1.6:1. In 2014, psychologist Stephen Ceci and his collaborators found boys did better than girls across the percentiles. For example, a girl scoring in the top 10% of her sex would only be in the top 20% among the boys. In 2010, psychologist Jonathan Wai and his colleagues showed, by analyzing data from three decades involving 1.6 million intellectually gifted seventh graders from the Duke University Talent Identification Program (TIP), that in the 1980s the gender gap in the mathematics section of the SAT among students scoring in the top 0.01% was 13.5:1 in favor of boys but dropped to 3.8:1 by the 1990s. The dramatic sex ratio from the 1980s replicates a different study using a sample from Johns Hopkins University. This ratio is similar to that observed for the ACT mathematics and science scores between the early 1990s and the late 2000s. It remained largely unaltered at the end of the 2000s. Sex differences in SAT mathematics scores began making themselves apparent at the level of 400 points and above. In the late 2000s, for every female who scored a perfect 800 on the SAT mathematics test, there were two males.

Some researchers point to evidence in support of greater male variability in verbal and quantitative reasoning skills. Greater male variability has been found in body weight, height, and cognitive abilities across cultures, leading to a larger number of males in the lowest and highest distributions of testing. Consequently, a higher number of males are found in both the upper and lower extremes of the performance distributions of the mathematics sections of standardized tests such as the SAT, resulting in the observed gender discrepancy. Paradoxically, this is at odds with the tendency of girls to have higher classroom scores than boys, proving that they do not lack scholastic aptitude. However, boys tend to do better on standardized test questions not directly related to the curriculum.

On the other hand, Wai and his colleagues found that both sexes in the top 5% appeared to be more or less at parity when it comes to the verbal section of the SAT, though girls have gained a slight but noticeable edge over boys starting in the mid-1980s. Psychologist David Lubinski, who conducted longitudinal studies of seventh graders who scored exceptionally high on the SAT, found a similar result. Girls generally had better verbal reasoning skills and boys mathematical skills. This reflects other research on the cognitive ability of the general population rather than just the 95th percentile and up.

Although aspects of testing such as stereotype threat are a concern, research on the predictive validity of the SAT has demonstrated that it tends to be a more accurate predictor of female GPA in university as compared to male GPA.

In strategizing

Mathematical problems on the SAT can be broadly categorized into two groups: conventional and unconventional. Conventional problems can be handled routinely via familiar formulas or algorithms while unconventional ones require more creative thought in order to make unusual use of familiar methods of solution or to come up with the specific insights necessary for solving those problems. In 2000, ETS psychometrician Ann M. Gallagher and her colleagues analyzed how students handled disclosed SAT mathematics questions in self-reports. They found that for both sexes, the most favored approach was to use formulas or algorithms learned in class. When that failed, however, males were more likely than females to identify the suitable methods of solution. Previous research suggested that males were more likely to explore unusual paths to solution whereas females tended to stick to what they had learned in class and that females were more likely to identify the appropriate approaches if such required nothing more than mastery of classroom materials.

In confidence

Older versions of the SAT did ask students how confident they were in their mathematical aptitude and verbal reasoning ability, specifically, whether or not they believed they were in the top 10%. Devin G. Pope analyzed data of over four million test takers from the late 1990s to the early 2000s and found that high scorers were more likely to be confident they were in the top 10%, with the top scorers reporting the highest levels of confidence. But there were some noticeable gaps between the sexes. Men tended to be much more confident in their mathematical aptitude than women. For example, among those who scored 700 on the mathematics section, 67% of men answered they believed they were in the top 10% whereas only 56% of women did the same. Women, on the other hand, were slightly more confident in their verbal reasoning ability than men.

In glucose metabolism

Cognitive neuroscientists Richard Haier and Camilla Persson Benbow employed positron emission tomography (PET) scans to investigate the rate of glucose metabolism among students who have taken the SAT. They found that among men, those with higher SAT mathematics scores exhibited higher rates of glucose metabolism in the temporal lobes than those with lower scores, contradicting the brain-efficiency hypothesis. This trend, however, was not found among women, for whom the researchers could not find any cortical regions associated with mathematical reasoning. Both sexes scored the same on average in their sample and had the same rates of cortical glucose metabolism overall. According to Haier and Benbow, this is evidence for the structural differences of the brain between the sexes.

Association with race and ethnicity

SAT Verbal average scores by race or ethnicity from 1986–87 to 2004–05

SAT Verbal average scores by race or ethnicity from 1986–87 to 2004–05 SAT Math average scores by race or ethnicity from 1986–87 to 2004–05

SAT Math average scores by race or ethnicity from 1986–87 to 2004–05

A 2001 meta-analysis of the results of 6,246,729 participants tested for cognitive ability or aptitude found a difference in average scores between black and white students of around 1.0 standard deviation, with comparable results for the SAT (2.4 million test takers). Similarly, on average, Hispanic and Amerindian students perform on the order of one standard deviation lower on the SAT than white and Asian students. Mathematics appears to be the more difficult part of the exam. In 1996, the black-white gap in the mathematics section was 0.91 standard deviations, but by 2020, it fell to 0.79. In 2013, Asian Americans as a group scored 0.38 standard deviations higher than whites in the mathematics section.

Some researchers believe that the difference in scores is closely related to the overall achievement gap in American society between students of different racial groups. This gap may be explainable in part by the fact that students of disadvantaged racial groups tend to go to schools that provide lower educational quality. This view is supported by evidence that the black-white gap is higher in cities and neighborhoods that are more racially segregated. Other research cites poorer minority proficiency in key coursework relevant to the SAT (English and math), as well as peer pressure against students who try to focus on their schoolwork ("acting white"). Cultural issues are also evident among black students in wealthier households, with high achieving parents. John Ogbu, a Nigerian-American professor of anthropology, concluded that instead of looking to their parents as role models, black youth chose other models like rappers and did not make an effort to be good students.

One set of studies has reported differential item functioning, namely, that some test questions function differently based on the racial group of the test taker, reflecting differences in ability to understand certain test questions or to acquire the knowledge required to answer them between groups. In 2003, Freedle published data showing that black students have had a slight advantage on the verbal questions that are labeled as difficult on the SAT, whereas white and Asian students tended to have a slight advantage on questions labeled as easy. Freedle argued that these findings suggest that "easy" test items use vocabulary that is easier to understand for white middle class students than for minorities, who often use a different language in the home environment, whereas the difficult items use complex language learned only through lectures and textbooks, giving both student groups equal opportunities to acquiring it. The study was severely criticized by the ETS board, but the findings were replicated in a subsequent study by Santelices and Wilson in 2010.

There is no evidence that SAT scores systematically underestimate future performance of minority students. However, the predictive validity of the SAT has been shown to depend on the dominant ethnic and racial composition of the college. Some studies have also shown that African-American students under-perform in college relative to their white peers with the same SAT scores; researchers have argued that this is likely because white students tend to benefit from social advantages outside of the educational environment (for example, high parental involvement in their education, inclusion in campus academic activities, positive bias from same-race teachers and peers) which result in better grades.

Christopher Jencks concludes that as a group, African Americans have been harmed by the introduction of standardized entrance exams such as the SAT. This, according to him, is not because the tests themselves are flawed, but because of labeling bias and selection bias; the tests measure the skills that African Americans are less likely to develop in their socialization, rather than the skills they are more likely to develop. Furthermore, standardized entrance exams are often labeled as tests of general ability, rather than of certain aspects of ability. Thus, a situation is produced in which African-American ability is consistently underestimated within the education and workplace environments, contributing in turn to selection bias against them which exacerbates underachievement.

Among the major racial or ethnic groups of the United States, gaps in SAT mathematics scores are the greatest at the tails, with Hispanic and Latino Americans being the most likely to score at the lowest range and Asian Americans the highest. In addition, there is some evidence suggesting that if the test contains more questions of both the easy and difficult varieties, which would increase the variability of the scores, the gaps would be even wider. Given the distribution for Asians, for example, many could score higher than 800 if the test allowed them to. (See figure below.)

2020 was the year in which education worldwide was disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and indeed, the performance of students in the United States on standardized tests, such as the SAT, suffered. Yet the gaps persisted. According to the College Board, in 2020, while 83% of Asian students met the benchmark of college readiness in reading and writing and 80% in mathematics, only 44% and 21% of black students did those respective categories. Among whites, 79% met the benchmark for reading and writing and 59% did mathematics. For Hispanics and Latinos, the numbers were 53% and 30%, respectively. (See figure below.)

Test-taking population

By analyzing data from the National Center for Education Statistics, economists Ember Smith and Richard Reeves of the Brookings Institution deduced that the number of students taking the SAT increased at a rate faster than population and high-school graduation growth rates between 2000 and 2020. The increase was especially pronounced among Hispanics and Latinos. Even among whites, whose number of high-school graduates was shrinking, the number of SAT takers rose. In 2015, for example, 1.7 million students took the SAT, up from 1.6 million in 2013. But in 2019, a record-breaking 2.2 million students took the exam, compared to 2.1 million in 2018, another record-breaking year. The rise in the number of students taking the SAT was due in part to many school districts offering to administer the SAT during school days often at no further costs to the students. Some require students to take the SAT, regardless of whether or not they are going to college. However, in 2021, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the optional status of the SAT at many colleges and universities, only 1.5 million students took the test. But as testing centers reopened, ambitious students chose to take the SAT or the ACT to make themselves stand out from the competition regardless of the admissions policies of their preferred schools. Among the class of 2023, 1.9 million students took the test.

Psychologists Jean Twenge, W. Keith Campbell, and Ryne A. Sherman analyzed vocabulary test scores on the U.S. General Social Survey () and found that after correcting for education, the use of sophisticated vocabulary has declined between the mid-1970s and the mid-2010s across all levels of education, from below high school to graduate school. However, they cautioned against the use of SAT verbal scores to track the decline for while the College Board reported that SAT verbal scores had been decreasing, these scores were an imperfect measure of the vocabulary level of the nation as a whole because the test-taking demographic has changed and because more students took the SAT in the 2010s than in the 1970s, meaning there were more with limited ability who took it. However, as the frequency of reading for pleasure and the level of reading comprehension among American high-school students continue to decline, students who take the SAT might struggle to do well, even if reforms have been introduced to shorten the duration of the test and to reduce the number of questions associated with a given passage in the verbal portion of the test.

Use in non-collegiate contexts

By high-IQ societies

Certain high IQ societies, like Mensa, Intertel, the Prometheus Society and the Triple Nine Society, use scores from certain years as one of their admission tests. For instance, Intertel accepts scores (verbal and math combined) of at least 1300 on tests taken through January 1994; the Triple Nine Society accepts scores of 1450 or greater on SAT tests taken before April 1995, and scores of at least 1520 on tests taken between April 1995 and February 2005. Mensa accepts qualifying SAT scores earned on or before January 31, 1994.

By researchers

Because it is strongly correlated with general intelligence, the SAT has often been used as a proxy to measure intelligence by researchers, especially since 2004. In particular, scientists studying mathematically gifted individuals have been using the mathematics section of the SAT to identify subjects for their research.

A growing body of research indicates that SAT scores can predict individual success decades into the future, for example in terms of income and occupational achievements. A longitudinal study published in 2005 by educational psychologists Jonathan Wai, David Lubinski, and Camilla Benbow suggests that among the intellectually precocious (the top 1%), those with higher scores in the mathematics section of the SAT at the age of 12 were more likely to earn a PhD in the STEM fields, to have a publication, to register a patent, or to secure university tenure. Wai further showed that an individual's academic ability, as measured by the average SAT or ACT scores of the institution attended, predicted individual differences in income, even among the richest people of all, and being a member of the 'American elite', namely Fortune 500 CEOs, billionaires, federal judges, and members of Congress. Wai concluded that the American elite was also the cognitive elite. Gregory Park, Lubinski, and Benbow gave statistical evidence that intellectually gifted adolescents, as identified by SAT scores, could be expected to accomplish great feats of creativity in the future, both in the arts and in STEM.

The SAT is sometimes given to students at age 12 or 13 by organizations such as the Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth (SMPY), Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth, and the Duke University Talent Identification Program (TIP) to select, study, and mentor students of exceptional ability, that is, those in the top one percent. Among SMPY participants, those within the top quartile, as indicated by the SAT composite score (mathematics and verbal), were markedly more likely to have a doctoral degree, to have at least one publication in STEM, to earn income in the 95th percentile, to have at least one literary publication, or to register at least one patent than those in the bottom quartile. Duke TIP participants generally picked career tracks in STEM should they be stronger in mathematics, as indicated by SAT mathematics scores, or the humanities if they possessed greater verbal ability, as indicated by SAT verbal scores. For comparison, the bottom SMPY quartile is five times more likely than the average American to have a patent. Meanwhile, as of 2016, the shares doctorates among SMPY participants was 44% and Duke TIP 37%, compared to two percent among the general U.S. population. Consequently, the notion that beyond a certain point, differences in cognitive ability as measured by standardized tests such as the SAT cease to matter is gainsaid by the evidence.

In the 2010 paper which showed that the sex gap in SAT mathematics scores had dropped dramatically between the early 1980s and the early 1990s but had persisted for the next two decades or so, Wai and his colleagues argued that "sex differences in abilities in the extreme right tail should not be dismissed as no longer part of the explanation for the dearth of women in math-intensive fields of science."

By employers

Cognitive ability is correlated with job training outcomes and job performance. As such, some employers rely on SAT scores to assess the suitability of a prospective recruit, especially if the person has limited work experience. There is nothing new about this practice. Major companies and corporations have spent princely sums on learning how to avoid hiring errors and have decided that standardized test scores are a valuable tool in deciding whether or not a person is fit for the job. In some cases, a company might need to hire someone to handle proprietary materials of its own making, such as computer software. But since the ability to work with such materials cannot be assessed via external certification, it makes sense for such a firm to rely on something that is a proxy of measuring general intelligence. In other cases, a firm may not care about academic background but needs to assess a prospective recruit's quantitative reasoning ability, and what makes standardized test scores necessary. Several companies, especially those considered to be the most prestigious in industries such as investment banking and management consulting such as Goldman Sachs and McKinsey, have been reported to ask prospective job candidates about their SAT scores.

Nevertheless, some other top employers, such as Google, have eschewed the use of SAT or other standardized test scores unless the potential employee is a recent graduate. Google's Laszlo Bock explained to The New York Times, "We found that they don't predict anything." Educational psychologist Jonathan Wai suggested this might be due to the inability of the SAT to differentiate the intellectual capacities of those at the extreme right end of the distribution of intelligence. Wai told The New York Times, "Today the SAT is actually too easy, and that's why Google doesn't see a correlation. Every single person they get through the door is a super-high scorer."

Perception

Math–verbal achievement gap

Main article: Math–verbal achievement gapIn 2002, New York Times columnist Richard Rothstein argued that the U.S. math averages on the SAT and ACT continued their decade-long rise over national verbal averages on the tests while the averages of verbal portions on the same tests were floundering.

Optional SAT

During the 1960s and 1970s, there was a movement to drop achievement scores. After some time, the countries, states, and provinces that reintroduced them agreed that academic standards had dropped, students had studied less, and had taken their education less seriously. Testing requirements were reinstated in some places after research concluded that these high-stakes tests produced benefits that outweighed the costs. However, in a 2001 speech to the American Council on Education, Richard C. Atkinson, the president of the University of California, urged the dropping of aptitude tests such as the SAT I but not achievement tests such as the SAT II as a college admissions requirement. Atkinson's critique of the predictive validity and powers of the SAT has been contested by the University of California academic senate. In April 2020, the academic senate, which consisted of faculty members, voted 51–0 to restore the requirement of standardized test scores, but the governing board overruled the academic senate and did not reinstate the test requirement anyway. Because of the size of the Californian population, this decision might have an impact on U.S. higher education at large; schools looking to admit Californian students could have a harder time.

During the 2010s, over 1,230 American universities and colleges opted to stop requiring the SAT and the ACT for admissions, according to FairTest, an activist group opposing standardized entrance exams. Most, however, were small colleges, with the notable exceptions of the University of California system and the University of Chicago. Also on the list are institutions catering to niche students, such as religious colleges, arts and music conservatories, or nursing schools, and the majority of institutions in the Northeastern United States. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, around 1,600 institutions decided to waive the requirement of the SAT or the ACT for admissions because it was challenging both to administer and to take these tests, resulting in many cancellations. Some schools chose to make them optional on a temporary basis only, either for just one year, as in the case of Princeton University, or three, like the College of William & Mary. Others dropped the requirement completely. Some schools extended their moratorium on standardized entrance exams in 2021. This did not stop highly ambitious students from taking them, however, as many parents and teenagers were skeptical of the "optional" status of university entrance exams and wanted to make their applications more likely to catch the attention of admission officers. This led to complaints of registration sites crashing in the summer of 2020. On the other hand, the number of students applying to the more competitive of schools that had made SAT and ACT scores optional increased dramatically because the students thought they stood a chance. Ivy League institutions saw double-digit increases in the number of applications, as high as 51% in the case of Columbia University, while their admission rates, already in the single digits, fell, e.g. from 4.9% in 2020 to just 3.4% in 2021 at Harvard University. At the same time, interest in lower-status schools that did the same thing dropped precipitously; the college application process remains driven primarily by the preference for elite schools. 44% of students who used the Common Application—accepted by over 900 colleges and universities as of 2021—submitted SAT or ACT scores in the 2020–21 academic year, down from 77% in 2019–20. Those who did submit their test scores tended to hail from high-income families, to have at least one university-educated parent, and to be white or Asian.

Despite the fallout from Operation Varsity Blues, which found many wealthy parents illegally intervening to raise their children's standardized test scores, the SAT and the ACT remain popular among American parents and college-bound seniors, who are skeptical of the process of "holistic admissions" because they think it is rather opaque, as schools try to access characteristics not easily discerned via a number, hence the growth in the number of test takers attempting to make themselves more competitive even if this parallels an increase in the number of schools declaring it optional. While holistic admissions might seem like a plausible alternative, the process of applying can be rather stressful for students and parents, and many get upset once they learn that someone else got into the school that rejected them despite having lower SAT scores and GPAs. Holistic admissions notwithstanding, when merit-based scholarships are considered, standardized test scores might be the tiebreakers, as these are highly competitive. Scholarships and financial aid could help students and their parents significantly cut the cost of higher education, especially in times of economic hardship. Moreover, the most selective of schools might have no better options than using standardized test scores in order to quickly prune the number of applications worth considering, for holistic admissions consume valuable time and other resources.

Following the 2023 ruling by the Supreme Court of the United States against race-based admissions as a form of affirmative action, a number of schools have signaled their intent to continue pursuing ethnic diversity. One way for them to adapt to the new legal reality is to drop the requirement of standardized testing, making it more difficult for potential plaintiffs (Asian Americans in the twin cases of SFFA v. Harvard and SFFA v UNC) to find concrete evidence for their allegations of discrimination.