Page version status

This is an accepted version of this page

| Sneeze | |

|---|---|

The function of sneezing is to expel irritants from the nasal cavity. The function of sneezing is to expel irritants from the nasal cavity. | |

| Biological system | Respiratory system |

| Health | Beneficial |

| Action | Involuntary |

| Stimuli | Irritants of the nasal mucosa Light Cold air Snatiation Allergy Infection |

| Method | Expulsion of air through nose/mouth |

| Outcome | Removal of irritant |

A sneeze (also known as sternutation) is a semi-autonomous, convulsive expulsion of air from the lungs through the nose and mouth, usually caused by foreign particles irritating the nasal mucosa. A sneeze expels air forcibly from the mouth and nose in an explosive, spasmodic involuntary action. This action allows for mucus to escape through the nasal cavity and saliva to escape from the oral cavity. Sneezing is possibly linked to sudden exposure to bright light (known as photic sneeze reflex), sudden change (drop) in temperature, breeze of cold air, a particularly full stomach, exposure to allergens, or viral infection. Because sneezes can spread disease through infectious aerosol droplets, it is recommended to cover one's mouth and nose with the forearm, the inside of the elbow, a tissue or a handkerchief while sneezing. In addition to covering the mouth, looking down is also recommended to change the direction of the droplets spread and avoid high concentration in the human breathing heights.

The function of sneezing is to expel mucus containing foreign particles or irritants and cleanse the nasal cavity. During a sneeze, the soft palate and palatine uvula depress while the back of the tongue elevates to partially close the passage to the mouth, creating a venturi (similar to a carburetor) due to Bernoulli's principle so that air ejected from the lungs is accelerated through the mouth and thus creating a low pressure point at the back of the nose. This way air is forced in through the front of the nose and the expelled mucus and contaminants are launched out the mouth. Sneezing with the mouth closed does expel mucus through the nose but is not recommended because it creates a very high pressure in the head and is potentially harmful.

Sneezing cannot occur during sleep due to REM atonia – a bodily state where motor neurons are not stimulated and reflex signals are not relayed to the brain. Sufficient external stimulants, however, may cause a person to wake from sleep to sneeze, but any sneezing occurring afterwards would take place with a partially awake status at minimum.

When sneezing, humans eyes automatically close due to the involuntary reflex during sneeze.

Description

Problems playing this file? See media help.

Sneezing typically occurs when foreign particles or sufficient external stimulants pass through the nasal hairs to reach the nasal mucosa. This triggers the release of histamines, which irritate the nerve cells in the nose, resulting in signals being sent to the brain to initiate the sneeze through the trigeminal nerve network. The brain then relates this initial signal, activates the pharyngeal and tracheal muscles and creates a large opening of the nasal and oral cavities, resulting in a powerful release of air and bioparticles. The powerful nature of a sneeze is attributed to its involvement of numerous organs of the upper body – it is a reflexive response involving the face, throat, and chest muscles. Sneezing is also triggered by sinus nerve stimulation caused by nasal congestion and allergies.

The neural regions involved in the sneeze reflex are located in the brainstem along the ventromedial part of the spinal trigeminal nucleus and the adjacent pontine-medullary lateral reticular formation. This region appears to control the epipharyngeal, intrinsic laryngeal and respiratory muscles, and the combined activity of these muscles serve as the basis for the generation of a sneeze.

The sneeze reflex involves contraction of a number of different muscles and muscle groups throughout the body, typically including the eyelids. The common suggestion that it is impossible to sneeze with one's eyes open is, however, inaccurate. Other than irritating foreign particles, allergies or possible illness, another stimulus is sudden exposure to bright light – a condition known as photic sneeze reflex (PSR). Walking out of a dark building into sunshine may trigger PSR, or the ACHOO (autosomal dominant compulsive helio-ophthalmic outbursts of sneezing) syndrome as it is also called. The tendency to sneeze upon exposure to bright light is an autosomal dominant trait and affects 18–35% of the human population. A rarer trigger, observed in some individuals, is the fullness of the stomach immediately after a large meal. This is known as snatiation and is regarded as a medical disorder passed along genetically as an autosomal dominant trait.

Epidemiology

While generally harmless in healthy individuals, sneezes spread disease through the infectious aerosol droplets, commonly ranging from 0.5 to 5 μm. A sneeze can produce 40,000 droplets. To reduce the possibility of thus spreading disease (such as the flu), one holds the forearm, the inside of the elbow, a tissue or a handkerchief in front of one's mouth and nose when sneezing. Using one's hand for that purpose has recently fallen into disuse as it is considered inappropriate, since it promotes spreading germs through human contact (such as handshaking) or by commonly touched objects (most notably doorknobs).

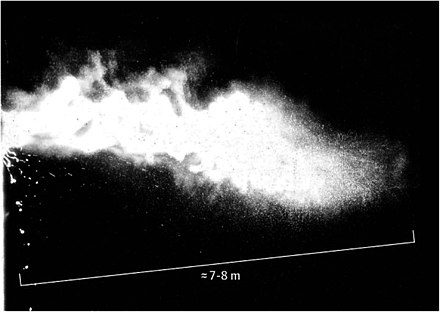

Until recently, the maximum visible distance over which the sneeze plumes (or puffs) travel was observed at 0.6 metres (2.0 ft), and the maximum sneeze velocity derived was 4.5 m/s (about 10 mph). In 2020, sneezes were recorded generating plumes of up to 8 meters (26 ft).

Prevention

Proven methods to reduce sneezing generally advocate reducing interaction with irritants, such as keeping pets out of the house to avoid animal dander; ensuring the timely and continuous removal of dirt and dust particles through proper housekeeping; replacing filters for furnaces and air-handling units; air filtration devices and humidifiers; and staying away from industrial and agricultural zones. Tickling the roof of the mouth with the tongue can stop a sneeze. Some people, however, find sneezes to be pleasurable and would not want to prevent them.

Holding in sneezes, such as by pinching the nose or holding one's breath, is not recommended as the air pressure places undue stress on the lungs and airways. One computer simulation suggests holding in a sneeze results in a burst of air pressure of 39 kPa, approximately 24 times that of a normal sneeze.

In 1884, biologist Henry Walter Bates elucidated the impact of light on the sneezing reflex (Bates H.W. 1881–84. Biologia Centrali-Americana Insecta. Coleoptera. Volume I, Part 1.). He observed that individuals were only capable of sneezing when they felt in control of their entire environment. Consequently, he inferred that people were unable to sneeze in the dark. However, this hypothesis was later debunked.

History

In ancient Greece, sneezes were believed to be prophetic signs from the gods. In 401 BC, for instance, the Athenian general Xenophon gave a speech exhorting his fellow soldiers to fight against the Persians. A soldier underscored his conclusion with a sneeze. Thinking that this sneeze was a favorable sign from the gods, the soldiers were impressed. Another divine moment of sneezing for the Greeks occurs in the story of Odysseus. His waiting wife Penelope, hearing Odysseus may be alive, says that he and his son would take revenge on the suitors if he were to return. At that moment, their son sneezes loudly and Penelope laughs with joy, reassured that it is a sign from the gods (Odyssey 17: 541–550). It may be because this belief survived through the centuries, that in certain parts of Greece today, when someone is asserting something and the listener sneezes promptly at the end of the assertion, the former responds "bless you and I am speaking the truth", or "bless you and here is the truth" ("γεια σου κι αλήθεια λέω", ya sou ki alithia leo, or "γεια σου και να κι η αλήθεια", ya sou ke na ki i alithia). A similar practice is also followed in India. If either the person just having made a not most obvious statement in Flemish, or some listener sneezes, often one of the listeners will say "It is beniesd", literally "It's sneezed upon", as if a proof of truth – usually self-ironically recalling this old superstitious habit, without either suggesting doubt or intending an actual confirmation, but making any apology by the sneezer for the interruption superfluous as the remark is received by smiles.

In Europe, principally around the early Middle Ages, it was believed that one's life was in fact tied to one's breath – a belief reflected in the word "expire" (originally meaning "to exhale") gaining the additional meaning of "to come to an end" or "to die". This connection, coupled with the significant amount of breath expelled from the body during a sneeze, had likely led people to believe that sneezing could easily be fatal. Such a theory could explain the reasoning behind the traditional English phrase, "God bless you", in response to a sneeze, the origins of which are not entirely clear. Sir Raymond Henry Payne Crawfurd, for instance, the registrar of the Royal College of Physicians, in his 1909 book, "The Last Days of Charles II", states that, when the controversial monarch was on his deathbed, his medical attendants administered a concoction of cowslips and extract of ammonia to promote sneezing. However, it is not known if this promotion of sneezing was done to hasten his death (as coup de grâce) or as an ultimate attempt at treatment.

In certain parts of East Asia, particularly in Chinese culture, Korean culture, Japanese culture and Vietnamese culture, a sneeze without an obvious cause was generally perceived as a sign that someone was talking about the sneezer at that very moment. This can be seen in the Book of Songs (a collection of Chinese poems) in ancient China as early as 1000 BC, and in Japan this belief is still depicted in present-day manga and anime. In China, Vietnam, South Korea, and Japan, for instance, there is a superstition that if talking behind someone's back causes the person being talked about to sneeze; as such, the sneezer can tell if something good is being said (one sneeze), someone is thinking about you (two sneezes in a row), even if someone is in love with you (three sneezes in a row) or if this is a sign that they are about to catch a cold (multiple sneezes).

Parallel beliefs are known to exist around the world, particularly in contemporary Greek, Slavic, Celtic, English, French, and Indian cultures. Similarly, in Nepal, sneezers are believed to be remembered by someone at that particular moment.

In English, the onomatopoeia for sneezes is usually spelled 'achoo' and it is similar to that of different cultures.

Culture

In Indian culture, especially in northern parts of India, Bengali (Bangladesh and Bengal of India) culture and also in Iran, it has been a common superstition that a sneeze taking place before the start of any work was a sign of impending bad interruption. It was thus customary to pause in order to drink water or break any work rhythm before resuming the job at hand in order to prevent any misfortune from occurring.

In Polish culture, especially in the Kresy Wschodnie borderlands, a popular belief persists that sneezes may be an inauspicious sign that, depending on the local version, either someone unspecified or one's mother-in-law speaks ill of the person sneezing at that moment. In other regions, however, this superstition concerns hiccups rather than sneezing. As with other Catholic countries, such as Mexico, Italy, or Ireland, the remnants of pagan culture are fostered in Polish peasant idiosyncratic superstitions.

The practice among Islamic culture, in turn, has largely been based on various prophetic traditions and the teachings of Muhammad. An example of this is Al-Bukhaari's narrations from Abu Hurayrah that Muhammad once said:

When one of you sneezes, let him say, "Al-hamdu-Lillah" (Praise be to God), and let his brother or companion say to him, "Yarhamuk Allah" (May God have mercy on you). If he says, "Yarhamuk-Allah", then let say, "Yahdeekum Allah wa yuslihu baalakum" (May God guide you and rectify your condition).

Verbal responses

Main article: Response to sneezingIn English-speaking countries, one common verbal response to another person's sneeze is " bless you". Even with "God", the declaration may be said by a person without religious intent. Another, less common, verbal response in the United States and Canada to another's sneeze is "Gesundheit", which is a German word that means, appropriately, 'health'.

Several hypotheses exist for why the custom arose of saying "bless you" or "God bless you" in the context of sneezing:

- Some say it came into use during the plague pandemics of the 14th century. Blessing the individual after showing such a symptom was thought to prevent possible impending death due to the lethal disease.

- In Renaissance times, a superstition was formed claiming one's heart stopped for a very brief moment during the sneeze; saying bless you was a sign of prayer that the heart would not fail.

Sexuality

See also: Sexually induced sneezingSome people may sneeze during the initial phases of sexual arousal. Doctors suspect that the phenomenon might arise from a case of crossed wires in the autonomic nervous system, which regulates a number of functions in the body, including, but not limited to, rousing the genitals during sexual arousal. The nose, like the genitals, contains erectile tissue. This phenomenon may prepare the vomeronasal organ for increased detection of pheromones.

A sneeze has been compared to an orgasm, since both orgasms and sneeze reflexes involve tingling, bodily stretching, tension and release. On this subject, sexologist Vanessa Thompson from the University of Sydney states, "Sneezing and orgasms both produce feel-good chemicals called endorphins but the amount produced by a sneeze is far less than an orgasm."

According to Dr. Holly Boyer from the University of Minnesota, there is a pleasurable effect during a sneeze, where she states, "the muscle tension that builds up in your chest causes pressure, and when you sneeze and the muscles relax, it releases pressure. Anytime you release pressure, it feels good...There's also some evidence that endorphins are released, which causes your body to feel good". Endorphins induce the brain's reward system, and because sneezes occur in a quick burst, so does the pleasure.

In non-humans

Sneezing is not confined to humans or even mammals. Many animals including cats, dogs, chickens and iguanas sneeze. African wild dogs use sneezing as a form of communication, especially when considering a consensus in a pack on whether or not to hunt. Some breeds of dog are predisposed to reverse sneezing.

See also

References

- "Sneeze". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

- "Sleep On, Sneeze Not". A Moment of Science. Indiana University. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- "The eye-popping truth about why we close our eyes when we sneeze". NBC News. 2013-04-12. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- Nonaka S, Unno T, Ohta Y, Mori S (March 1990). "Sneeze-evoking region within the brainstem". Brain Research. 511 (2): 265–270. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(90)90171-7. PMID 2139800. S2CID 26718567.

- "Myth: Can sneezing with your eyes open make your eyeballs pop out?". Myth Busters.

- Goldman JG (June 24, 2015). "Why looking at the sun makes us sneeze". BBC Future. BBC. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- Breitenbach RA, Swisher PK, Kim MK, Patel BS (December 1993). "The photic sneeze reflex as a risk factor to combat pilots". Military Medicine. 158 (12): 806–809. doi:10.1093/milmed/158.12.806. PMID 8108024. S2CID 10884414.

- Teebi, A S; al-Saleh, Q A (August 1989). "Autosomal dominant sneezing disorder provoked by fullness of stomach". Journal of Medical Genetics. 26 (8): 539–540. doi:10.1136/jmg.26.8.539. ISSN 0022-2593. PMC 1015683. PMID 2769729.

- Cole EC, Cook CE (August 1998). "Characterization of infectious aerosols in health care facilities: an aid to effective engineering controls and preventive strategies". American Journal of Infection Control. 26 (4): 453–64. doi:10.1016/S0196-6553(98)70046-X. PMC 7132666. PMID 9721404.

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Central Maine Medical Center (7 March 2012). "Why Don't We Do It In Our Sleeves". CoughSafe. CMMC, St. Mary's Hospital, Maine Medical Association. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- Tang JW, Nicolle AD, Klettner CA, Pantelic J, Wang L, Suhaimi AB, et al. (2013). "Airflow dynamics of human jets: sneezing and breathing - potential sources of infectious aerosols". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e59970. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...859970T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059970. PMC 3613375. PMID 23560060.

- Sommerstein, R; Fux, CA; Vuichard-Gysin, D; Abbas, M; Marschall, J; Balmelli, C; Troillet, N; Harbarth, S; Schlegel, M; Widmer, A; Swissnoso. (6 July 2020). "Risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission by aerosols, the rational use of masks, and protection of healthcare workers from COVID-19". Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. 9 (1): 100. doi:10.1186/s13756-020-00763-0. ISSN 2047-2994. PMC 7336106. PMID 32631450.

- Laurie L. Dove (2015). "Why does tickling the roof of your mouth with your tongue stifle a sneeze?". HowStuffWorks.com.

- Adkinson NF Jr. (2003). "Phytomedicine". Middleton's Allergy: Principles and Practice (6th ed.). Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-01425-0.

- Setzen, Sean; Platt, Michael (May 2019). "The Dangers of Sneezing: A Review of Injuries". American Journal of Rhinology and Allergy. 33 (3): 331–337. doi:10.1177/1945892418823147. PMID 30616365. S2CID 58587363.

- Rahiminejad, Mohammad; Haghighi, Abdalrahman; Dastan, Alireza; Abouali, Omid; Farid, Mehrdad; Ahmadi, Goodarz (April 1, 2016). "Computer Simulations of Pressure and Velocity fields in Human Upper Airway during Sneezing". Computers in Biology and Medicine. 71 (71): 115–127. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2016.01.022. PMID 26914240.

- Xenophon. Anabasis. Book 3, chapter 2, paragraph 9.

- "Why Do We Say "Waheguru!" Every Time We Sneeze?". Sikhing Answers – V.

- "Why do we say this when a person sneezes or hiccups?". India Study Channel. 24 January 2015.

- Gezelle G (1999). Boets J (ed.). Volledig Dichtwerk [Complete Poetry] (in Western Frisian). Lannoo Uitgeverij. ISBN 978-90-209-3510-3.

- Wylie A (1927). "Rhinology and laryngology in literature and Folk-Lore". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 42 (2): 81–87. doi:10.1017/S0022215100029959. S2CID 71281077.

- 詩經·終風 [The Book of Songs - Final Wind] (in Chinese).

If you speak insomnia, you will sneeze.

- "Where Did The Word "Achoo" Come From?". Dictionary.com. 2020-08-18. Retrieved 2021-10-11.

- Bukhari SA. "When somebody sneezes, what should be said?". Sunnah.com.

- "Does your heart stop when you sneeze?". Everyday Mysteries: Fun Science Facts. The Library of Congress.

- "'Bless you': Social convention or theological statement? | UU World Magazine". www.uuworld.org. 2011-07-11. Retrieved 2023-08-25.

- Bhutta MF, Maxwell H (December 2008). "Sneezing induced by sexual ideation or orgasm: an under-reported phenomenon". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 101 (12): 587–591. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2008.080262. PMC 2625373. PMID 19092028.

- Mackenzie J (1898). "The physiological and pathological relations between the nose and the sexual apparatus of man". The Journal of Laryngology, Rhinology, and Otology. 13 (3): 109–123. doi:10.1017/S1755146300166016. S2CID 196423179.

- Gerbis N (28 November 2012). "Is Sneezing Really Like an Orgasm?". LiveScience.

- Terlato P (1 June 2015). "We asked a sexologist if the theory about sneezing and orgasms was true – here's what she said". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- DeRusha J (17 April 2012). "Good Question: Why Does Sneezing Feel So Good?". CBS Minnesota.

- "Why Cats Sneeze". WebMD.

- "My Pet Is Sneezing and Snorting. What's Going On?". Vet Street. 19 September 2011.

- "Why is my Chicken Sneezing?". Keeping Chickens. Archived from the original on 2015-05-17. Retrieved 2015-04-18.

- Kaplan M (1 January 2014). "Sneezing and Yawning". Herp Care Collection.

- Walker RH, King AJ, McNutt JW, Jordan NR (September 2017). "Lycaon pictus) use variable quorum thresholds facilitated by sneezes in collective decisions". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 284 (1862): 20170347. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.0347. PMC 5597819. PMID 28878054.

Further reading

- Adams C (1987). "If you hold your eyelids open while sneezing, will your eyes pop out?". The Straight Dope.

- Mikkelson B (2001). "Bless You!". Urban Legends Reference Pages.

- Wilson T (1997). "Why do we sneeze when we look at the sun?". MadSci Network.

- Sheckley, Robert (1956). ""Protection," a short story about sneezing". Archived from the original on May 16, 2010.

- Knowlson, T. Sharper (1910). "The Origins of Popular Superstitions and Customs". a book that listed many superstitions and customs that are still common today.

- "Cold and flu advice". NHS Direct. Archived from the original on 2010-01-05. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- Fantham E. "Ancient Sneezing: A Gift from the Gods". Princeton. NPR Radio.

- Sherborn MG (15 June 2004). "Why do my eyes close every time I sneeze?". The Boston Globe.

External links

| Common cold | |

|---|---|

| Viruses | |

| Symptoms | |

| Complications | |

| Drugs | |