Medical diagnostic method

| Magnetic resonance imaging | |

|---|---|

| Para-sagittal MRI of the head, with aliasing artifacts (nose and forehead appear at the back of the head) | |

| Synonyms | Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI), magnetic resonance tomography (MRT) |

| ICD-9-CM | 88.91 |

| MeSH | D008279 |

| MedlinePlus | 003335 |

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a medical imaging technique used in radiology to generate pictures of the anatomy and the physiological processes inside the body. MRI scanners use strong magnetic fields, magnetic field gradients, and radio waves to form images of the organs in the body. MRI does not involve X-rays or the use of ionizing radiation, which distinguishes it from computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans. MRI is a medical application of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) which can also be used for imaging in other NMR applications, such as NMR spectroscopy.

MRI is widely used in hospitals and clinics for medical diagnosis, staging and follow-up of disease. Compared to CT, MRI provides better contrast in images of soft tissues, e.g. in the brain or abdomen. However, it may be perceived as less comfortable by patients, due to the usually longer and louder measurements with the subject in a long, confining tube, although "open" MRI designs mostly relieve this. Additionally, implants and other non-removable metal in the body can pose a risk and may exclude some patients from undergoing an MRI examination safely.

MRI was originally called NMRI (nuclear magnetic resonance imaging), but "nuclear" was dropped to avoid negative associations. Certain atomic nuclei are able to absorb radio frequency (RF) energy when placed in an external magnetic field; the resultant evolving spin polarization can induce an RF signal in a radio frequency coil and thereby be detected. In other words, the nuclear magnetic spin of protons in the hydrogen nuclei resonates with the RF incident waves and emit coherent radiation with compact direction, energy (frequency) and phase. This coherent amplified radiation is easily detected by RF antennas close to the subject being examined. It is a process similar to masers. In clinical and research MRI, hydrogen atoms are most often used to generate a macroscopic polarized radiation that is detected by the antennas. Hydrogen atoms are naturally abundant in humans and other biological organisms, particularly in water and fat. For this reason, most MRI scans essentially map the location of water and fat in the body. Pulses of radio waves excite the nuclear spin energy transition, and magnetic field gradients localize the polarization in space. By varying the parameters of the pulse sequence, different contrasts may be generated between tissues based on the relaxation properties of the hydrogen atoms therein.

Since its development in the 1970s and 1980s, MRI has proven to be a versatile imaging technique. While MRI is most prominently used in diagnostic medicine and biomedical research, it also may be used to form images of non-living objects, such as mummies. Diffusion MRI and functional MRI extend the utility of MRI to capture neuronal tracts and blood flow respectively in the nervous system, in addition to detailed spatial images. The sustained increase in demand for MRI within health systems has led to concerns about cost effectiveness and overdiagnosis.

Mechanism

Construction and physics

Main article: Physics of magnetic resonance imaging

In most medical applications, hydrogen nuclei, which consist solely of a proton, that are in tissues create a signal that is processed to form an image of the body in terms of the density of those nuclei in a specific region. Given that the protons are affected by fields from other atoms to which they are bonded, it is possible to separate responses from hydrogen in specific compounds. To perform a study, the person is positioned within an MRI scanner that forms a strong magnetic field around the area to be imaged. First, energy from an oscillating magnetic field is temporarily applied to the patient at the appropriate resonance frequency. Scanning with X and Y gradient coils causes a selected region of the patient to experience the exact magnetic field required for the energy to be absorbed. The atoms are excited by a RF pulse and the resultant signal is measured by a receiving coil. The RF signal may be processed to deduce position information by looking at the changes in RF level and phase caused by varying the local magnetic field using gradient coils. As these coils are rapidly switched during the excitation and response to perform a moving line scan, they create the characteristic repetitive noise of an MRI scan as the windings move slightly due to magnetostriction. The contrast between different tissues is determined by the rate at which excited atoms return to the equilibrium state. Exogenous contrast agents may be given to the person to make the image clearer.

The major components of an MRI scanner are the main magnet, which polarizes the sample, the shim coils for correcting shifts in the homogeneity of the main magnetic field, the gradient system which is used to localize the region to be scanned and the RF system, which excites the sample and detects the resulting NMR signal. The whole system is controlled by one or more computers.

Problems playing this file? See media help.

MRI requires a magnetic field that is both strong and uniform to a few parts per million across the scan volume. The field strength of the magnet is measured in teslas – and while the majority of systems operate at 1.5 T, commercial systems are available between 0.2 and 7 T. 3T MRI systems, also called 3 Tesla MRIs, have stronger magnets than 1.5 systems and are considered better for images of organs and soft tissue. Whole-body MRI systems for research applications operate in e.g. 9.4T, 10.5T, 11.7T. Even higher field whole-body MRI systems e.g. 14 T and beyond are in conceptual proposal or in engineering design. Most clinical magnets are superconducting magnets, which require liquid helium to keep them at low temperatures. Lower field strengths can be achieved with permanent magnets, which are often used in "open" MRI scanners for claustrophobic patients. Lower field strengths are also used in a portable MRI scanner approved by the FDA in 2020. Recently, MRI has been demonstrated also at ultra-low fields, i.e., in the microtesla-to-millitesla range, where sufficient signal quality is made possible by prepolarization (on the order of 10–100 mT) and by measuring the Larmor precession fields at about 100 microtesla with highly sensitive superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs).

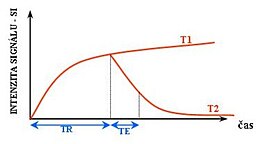

T1 and T2

Further information: Relaxation (NMR)

Each tissue returns to its equilibrium state after excitation by the independent relaxation processes of T1 (spin-lattice; that is, magnetization in the same direction as the static magnetic field) and T2 (spin-spin; transverse to the static magnetic field). To create a T1-weighted image, magnetization is allowed to recover before measuring the MR signal by changing the repetition time (TR). This image weighting is useful for assessing the cerebral cortex, identifying fatty tissue, characterizing focal liver lesions, and in general, obtaining morphological information, as well as for post-contrast imaging. To create a T2-weighted image, magnetization is allowed to decay before measuring the MR signal by changing the echo time (TE). This image weighting is useful for detecting edema and inflammation, revealing white matter lesions, and assessing zonal anatomy in the prostate and uterus.

The information from MRI scans comes in the form of image contrasts based on differences in the rate of relaxation of nuclear spins following their perturbation by an oscillating magnetic field (in the form of radiofrequency pulses through the sample). The relaxation rates are a measure of the time it takes for a signal to decay back to an equilibrium state from either the longitudinal or transverse plane.

Magnetization builds up along the z-axis in the presence of a magnetic field, B0, such that the magnetic dipoles in the sample will, on average, align with the z-axis summing to a total magnetization Mz. This magnetization along z is defined as the equilibrium magnetization; magnetization is defined as the sum of all magnetic dipoles in a sample. Following the equilibrium magnetization, a 90° radiofrequency (RF) pulse flips the direction of the magnetization vector in the xy-plane, and is then switched off. The initial magnetic field B0, however, is still applied. Thus, the spin magnetization vector will slowly return from the xy-plane back to the equilibrium state. The time it takes for the magnetization vector to return to its equilibrium value, Mz, is referred to as the longitudinal relaxation time, T1. Subsequently, the rate at which this happens is simply the reciprocal of the relaxation time: . Similarly, the time in which it takes for Mxy to return to zero is T2, with the rate . Magnetization as a function of time is defined by the Bloch equations.

T1 and T2 values are dependent on the chemical environment of the sample; hence their utility in MRI. Soft tissue and muscle tissue relax at different rates, yielding the image contrast in a typical scan.

The standard display of MR images is to represent fluid characteristics in black-and-white images, where different tissues turn out as follows:

| Signal | T1-weighted | T2-weighted |

|---|---|---|

| High |

|

|

| Intermediate |

|

|

| Low |

|

|

Diagnostics

Usage by organ or system

MRI has a wide range of applications in medical diagnosis and around 50,000 scanners are estimated to be in use worldwide. MRI affects diagnosis and treatment in many specialties although the effect on improved health outcomes is disputed in certain cases.

MRI is the investigation of choice in the preoperative staging of rectal and prostate cancer and has a role in the diagnosis, staging, and follow-up of other tumors, as well as for determining areas of tissue for sampling in biobanking.

Neuroimaging

Main article: Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain See also: Neuroimaging

MRI is the investigative tool of choice for neurological cancers over CT, as it offers better visualization of the posterior cranial fossa, containing the brainstem and the cerebellum. The contrast provided between grey and white matter makes MRI the best choice for many conditions of the central nervous system, including demyelinating diseases, dementia, cerebrovascular disease, infectious diseases, Alzheimer's disease and epilepsy. Since many images are taken milliseconds apart, it shows how the brain responds to different stimuli, enabling researchers to study both the functional and structural brain abnormalities in psychological disorders. MRI also is used in guided stereotactic surgery and radiosurgery for treatment of intracranial tumors, arteriovenous malformations, and other surgically treatable conditions using a device known as the N-localizer. New tools that implement artificial intelligence in healthcare have demonstrated higher image quality and morphometric analysis in neuroimaging with the application of a denoising system.

The record for the highest spatial resolution of a whole intact brain (postmortem) is 100 microns, from Massachusetts General Hospital. The data was published in NATURE on 30 October 2019.

Though MRI is used widely in research on mental disabilities, based on a 2024 systematic literature review and meta analysis commissioned by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), available research using MRI scans to diagnose ADHD showed great variability. The authors conclude that MRI cannot be reliably used to assist in making a clinical diagnosis of ADHD.

Cardiovascular

Main article: Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

Cardiac MRI is complementary to other imaging techniques, such as echocardiography, cardiac CT, and nuclear medicine. It can be used to assess the structure and the function of the heart. Its applications include assessment of myocardial ischemia and viability, cardiomyopathies, myocarditis, iron overload, vascular diseases, and congenital heart disease.

Musculoskeletal

Main article: Spinal fMRIApplications in the musculoskeletal system include spinal imaging, assessment of joint disease, and soft tissue tumors. Also, MRI techniques can be used for diagnostic imaging of systemic muscle diseases including genetic muscle diseases.

Swallowing movement of throat and oesophagus can cause motion artifact over the imaged spine. Therefore, a saturation pulse applied over this region the throat and oesophagus can help to avoid this artifact. Motion artifact arising due to pumping of the heart can be reduced by timing the MRI pulse according to heart cycles. Blood vessels flow artifacts can be reduced by applying saturation pulses above and below the region of interest.

Liver and gastrointestinal

Hepatobiliary MR is used to detect and characterize lesions of the liver, pancreas, and bile ducts. Focal or diffuse disorders of the liver may be evaluated using diffusion-weighted, opposed-phase imaging and dynamic contrast enhancement sequences. Extracellular contrast agents are used widely in liver MRI, and newer hepatobiliary contrast agents also provide the opportunity to perform functional biliary imaging. Anatomical imaging of the bile ducts is achieved by using a heavily T2-weighted sequence in magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Functional imaging of the pancreas is performed following administration of secretin. MR enterography provides non-invasive assessment of inflammatory bowel disease and small bowel tumors. MR-colonography may play a role in the detection of large polyps in patients at increased risk of colorectal cancer.

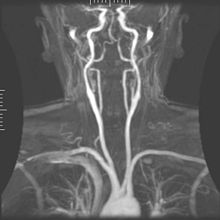

Angiography

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) generates pictures of the arteries to evaluate them for stenosis (abnormal narrowing) or aneurysms (vessel wall dilatations, at risk of rupture). MRA is often used to evaluate the arteries of the neck and brain, the thoracic and abdominal aorta, the renal arteries, and the legs (called a "run-off"). A variety of techniques can be used to generate the pictures, such as administration of a paramagnetic contrast agent (gadolinium) or using a technique known as "flow-related enhancement" (e.g., 2D and 3D time-of-flight sequences), where most of the signal on an image is due to blood that recently moved into that plane (see also FLASH MRI).

Techniques involving phase accumulation (known as phase contrast angiography) can also be used to generate flow velocity maps easily and accurately. Magnetic resonance venography (MRV) is a similar procedure that is used to image veins. In this method, the tissue is now excited inferiorly, while the signal is gathered in the plane immediately superior to the excitation plane—thus imaging the venous blood that recently moved from the excited plane.

Contrast agents

Main article: MRI contrast agentMRI for imaging anatomical structures or blood flow do not require contrast agents since the varying properties of the tissues or blood provide natural contrasts. However, for more specific types of imaging, exogenous contrast agents may be given intravenously, orally, or intra-articularly. Most contrast agents are either paramagnetic (e.g.: gadolinium, manganese, europium), and are used to shorten T1 in the tissue they accumulate in, or super-paramagnetic (SPIONs), and are used to shorten T2 and T2* in healthy tissue reducing its signal intensity (negative contrast agents). The most commonly used intravenous contrast agents are based on chelates of gadolinium, which is highly paramagnetic. In general, these agents have proved safer than the iodinated contrast agents used in X-ray radiography or CT. Anaphylactoid reactions are rare, occurring in approx. 0.03–0.1%. Of particular interest is the lower incidence of nephrotoxicity, compared with iodinated agents, when given at usual doses—this has made contrast-enhanced MRI scanning an option for patients with renal impairment, who would otherwise not be able to undergo contrast-enhanced CT.

Gadolinium-based contrast reagents are typically octadentate complexes of gadolinium(III). The complex is very stable (log K > 20) so that, in use, the concentration of the un-complexed Gd ions should be below the toxicity limit. The 9th place in the metal ion's coordination sphere is occupied by a water molecule which exchanges rapidly with water molecules in the reagent molecule's immediate environment, affecting the magnetic resonance relaxation time.

In December 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States announced in a drug safety communication that new warnings were to be included on all gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs). The FDA also called for increased patient education and requiring gadolinium contrast vendors to conduct additional animal and clinical studies to assess the safety of these agents. Although gadolinium agents have proved useful for patients with kidney impairment, in patients with severe kidney failure requiring dialysis there is a risk of a rare but serious illness, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, which may be linked to the use of certain gadolinium-containing agents. The most frequently linked is gadodiamide, but other agents have been linked too. Although a causal link has not been definitively established, current guidelines in the United States are that dialysis patients should only receive gadolinium agents where essential and that dialysis should be performed as soon as possible after the scan to remove the agent from the body promptly.

In Europe, where more gadolinium-containing agents are available, a classification of agents according to potential risks has been released. In 2008, a new contrast agent named gadoxetate, brand name Eovist (US) or Primovist (EU), was approved for diagnostic use: This has the theoretical benefit of a dual excretion path.

Sequences

Main article: MRI sequencesAn MRI sequence is a particular setting of radiofrequency pulses and gradients, resulting in a particular image appearance. The T1 and T2 weighting can also be described as MRI sequences.

Overview table

edit

This table does not include uncommon and experimental sequences.

| Group | Sequence | Abbr. | Physics | Main clinical distinctions | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spin echo | T1 weighted | T1 | Measuring spin–lattice relaxation by using a short repetition time (TR) and echo time (TE). |

Standard foundation and comparison for other sequences |

|

| T2 weighted | T2 | Measuring spin–spin relaxation by using long TR and TE times |

Standard foundation and comparison for other sequences |

| |

| Proton density weighted | PD | Long TR (to reduce T1) and short TE (to minimize T2). | Joint disease and injury.

|

| |

| Gradient echo (GRE) | Steady-state free precession | SSFP | Maintenance of a steady, residual transverse magnetisation over successive cycles. | Creation of cardiac MRI videos (pictured). |

|

| Effective T2 or "T2-star" |

T2* | Spoiled gradient recalled echo (GRE) with a long echo time and small flip angle | Low signal from hemosiderin deposits (pictured) and hemorrhages. |

| |

| Susceptibility-weighted | SWI | Spoiled gradient recalled echo (GRE), fully flow compensated, long echo time, combines phase image with magnitude image | Detecting small amounts of hemorrhage (diffuse axonal injury pictured) or calcium. |

| |

| Inversion recovery | Short tau inversion recovery | STIR | Fat suppression by setting an inversion time where the signal of fat is zero. | High signal in edema, such as in more severe stress fracture. Shin splints pictured: |

|

| Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery | FLAIR | Fluid suppression by setting an inversion time that nulls fluids | High signal in lacunar infarction, multiple sclerosis (MS) plaques, subarachnoid haemorrhage and meningitis (pictured). |

| |

| Double inversion recovery | DIR | Simultaneous suppression of cerebrospinal fluid and white matter by two inversion times. | High signal of multiple sclerosis plaques (pictured). |

| |

| Diffusion weighted (DWI) | Conventional | DWI | Measure of Brownian motion of water molecules. | High signal within minutes of cerebral infarction (pictured). |

|

| Apparent diffusion coefficient | ADC | Reduced T2 weighting by taking multiple conventional DWI images with different DWI weighting, and the change corresponds to diffusion. | Low signal minutes after cerebral infarction (pictured). |

| |

| Diffusion tensor | DTI | Mainly tractography (pictured) by an overall greater Brownian motion of water molecules in the directions of nerve fibers. |

|

| |

| Perfusion weighted (PWI) | Dynamic susceptibility contrast | DSC | Measures changes over time in susceptibility-induced signal loss due to gadolinium contrast injection. |

|

|

| Arterial spin labelling | ASL | Magnetic labeling of arterial blood below the imaging slab, which subsequently enters the region of interest. It does not need gadolinium contrast. | |||

| Dynamic contrast enhanced | DCE | Measures changes over time in the shortening of the spin–lattice relaxation (T1) induced by a gadolinium contrast bolus. | Faster Gd contrast uptake along with other features is suggestive of malignancy (pictured). |

| |

| Functional MRI (fMRI) | Blood-oxygen-level dependent imaging | BOLD | Changes in oxygen saturation-dependent magnetism of hemoglobin reflects tissue activity. | Localizing brain activity from performing an assigned task (e.g. talking, moving fingers) before surgery, also used in research of cognition. |

|

| Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and venography | Time-of-flight | TOF | Blood entering the imaged area is not yet magnetically saturated, giving it a much higher signal when using short echo time and flow compensation. | Detection of aneurysm, stenosis, or dissection |

|

| Phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging | PC-MRA | Two gradients with equal magnitude, but opposite direction, are used to encode a phase shift, which is proportional to the velocity of spins. | Detection of aneurysm, stenosis, or dissection (pictured). |  (VIPR) |

Specialized configurations

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy

Main articles: In vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy and Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopyMagnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) is used to measure the levels of different metabolites in body tissues, which can be achieved through a variety of single voxel or imaging-based techniques. The MR signal produces a spectrum of resonances that corresponds to different molecular arrangements of the isotope being "excited". This signature is used to diagnose certain metabolic disorders, especially those affecting the brain, and to provide information on tumor metabolism.

Magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) combines both spectroscopic and imaging methods to produce spatially localized spectra from within the sample or patient. The spatial resolution is much lower (limited by the available SNR), but the spectra in each voxel contains information about many metabolites. Because the available signal is used to encode spatial and spectral information, MRSI requires high SNR achievable only at higher field strengths (3 T and above). The high procurement and maintenance costs of MRI with extremely high field strengths inhibit their popularity. However, recent compressed sensing-based software algorithms (e.g., SAMV) have been proposed to achieve super-resolution without requiring such high field strengths.

Real-time

Real-time magnetic resonance imaging (RT-MRI) refers to the continuous monitoring of moving objects in real time. Traditionally, real-time MRI was possible only with low image quality or low temporal resolution. An iterative reconstruction algorithm removed limitations. Radial FLASH MRI (real-time) yields a temporal resolution of 20 to 30 milliseconds for images with an in-plane resolution of 1.5 to 2.0 mm. Real-time MRI adds information about diseases of the joints and the heart. In many cases MRI examinations become easier and more comfortable for patients, especially for the patients who cannot calm their breathing or who have arrhythmia.

Balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) imaging gives better image contrast between the blood pool and myocardium than FLASH MRI, at the cost of severe banding artifact when B0 inhomogeneity is strong.Interventional MRI

Main article: Interventional magnetic resonance imagingThe lack of harmful effects on the patient and the operator make MRI well-suited for interventional radiology, where the images produced by an MRI scanner guide minimally invasive procedures. Such procedures use no ferromagnetic instruments.

A specialized growing subset of interventional MRI is intraoperative MRI, in which an MRI is used in surgery. Some specialized MRI systems allow imaging concurrent with the surgical procedure. More typically, the surgical procedure is temporarily interrupted so that MRI can assess the success of the procedure or guide subsequent surgical work.

Magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound

In guided therapy, high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) beams are focused on a tissue, that are controlled using MR thermal imaging. Due to the high energy at the focus, the temperature rises to above 65 °C (150 °F) which completely destroys the tissue. This technology can achieve precise ablation of diseased tissue. MR imaging provides a three-dimensional view of the target tissue, allowing for the precise focusing of ultrasound energy. The MR imaging provides quantitative, real-time, thermal images of the treated area. This allows the physician to ensure that the temperature generated during each cycle of ultrasound energy is sufficient to cause thermal ablation within the desired tissue and if not, to adapt the parameters to ensure effective treatment.

Multinuclear imaging

See also: Helium-3 § Medical imagingHydrogen has the most frequently imaged nucleus in MRI because it is present in biological tissues in great abundance, and because its high gyromagnetic ratio gives a strong signal. However, any nucleus with a net nuclear spin could potentially be imaged with MRI. Such nuclei include helium-3, lithium-7, carbon-13, fluorine-19, oxygen-17, sodium-23, phosphorus-31 and xenon-129. Na and P are naturally abundant in the body, so they can be imaged directly. Gaseous isotopes such as He or Xe must be hyperpolarized and then inhaled as their nuclear density is too low to yield a useful signal under normal conditions. O and F can be administered in sufficient quantities in liquid form (e.g. O-water) that hyperpolarization is not a necessity. Using helium or xenon has the advantage of reduced background noise, and therefore increased contrast for the image itself, because these elements are not normally present in biological tissues.

Moreover, the nucleus of any atom that has a net nuclear spin and that is bonded to a hydrogen atom could potentially be imaged via heteronuclear magnetization transfer MRI that would image the high-gyromagnetic-ratio hydrogen nucleus instead of the low-gyromagnetic-ratio nucleus that is bonded to the hydrogen atom. In principle, heteronuclear magnetization transfer MRI could be used to detect the presence or absence of specific chemical bonds.

Multinuclear imaging is primarily a research technique at present. However, potential applications include functional imaging and imaging of organs poorly seen on H MRI (e.g., lungs and bones) or as alternative contrast agents. Inhaled hyperpolarized He can be used to image the distribution of air spaces within the lungs. Injectable solutions containing C or stabilized bubbles of hyperpolarized Xe have been studied as contrast agents for angiography and perfusion imaging. P can potentially provide information on bone density and structure, as well as functional imaging of the brain. Multinuclear imaging holds the potential to chart the distribution of lithium in the human brain, this element finding use as an important drug for those with conditions such as bipolar disorder.

Molecular imaging by MRI

Main article: Molecular imagingMRI has the advantages of having very high spatial resolution and is very adept at morphological imaging and functional imaging. MRI does have several disadvantages though. First, MRI has a sensitivity of around 10 mol/L to 10 mol/L, which, compared to other types of imaging, can be very limiting. This problem stems from the fact that the population difference between the nuclear spin states is very small at room temperature. For example, at 1.5 teslas, a typical field strength for clinical MRI, the difference between high and low energy states is approximately 9 molecules per 2 million. Improvements to increase MR sensitivity include increasing magnetic field strength and hyperpolarization via optical pumping or dynamic nuclear polarization. There are also a variety of signal amplification schemes based on chemical exchange that increase sensitivity.

To achieve molecular imaging of disease biomarkers using MRI, targeted MRI contrast agents with high specificity and high relaxivity (sensitivity) are required. To date, many studies have been devoted to developing targeted-MRI contrast agents to achieve molecular imaging by MRI. Commonly, peptides, antibodies, or small ligands, and small protein domains, such as HER-2 affibodies, have been applied to achieve targeting. To enhance the sensitivity of the contrast agents, these targeting moieties are usually linked to high payload MRI contrast agents or MRI contrast agents with high relaxivities. A new class of gene targeting MR contrast agents has been introduced to show gene action of unique mRNA and gene transcription factor proteins. These new contrast agents can trace cells with unique mRNA, microRNA and virus; tissue response to inflammation in living brains. The MR reports change in gene expression with positive correlation to TaqMan analysis, optical and electron microscopy.

Parallel MRI

It takes time to gather MRI data using sequential applications of magnetic field gradients. Even for the most streamlined of MRI sequences, there are physical and physiologic limits to the rate of gradient switching. Parallel MRI circumvents these limits by gathering some portion of the data simultaneously, rather than in a traditional sequential fashion. This is accomplished using arrays of radiofrequency (RF) detector coils, each with a different 'view' of the body. A reduced set of gradient steps is applied, and the remaining spatial information is filled in by combining signals from various coils, based on their known spatial sensitivity patterns. The resulting acceleration is limited by the number of coils and by the signal to noise ratio (which decreases with increasing acceleration), but two- to four-fold accelerations may commonly be achieved with suitable coil array configurations, and substantially higher accelerations have been demonstrated with specialized coil arrays. Parallel MRI may be used with most MRI sequences.

After a number of early suggestions for using arrays of detectors to accelerate imaging went largely unremarked in the MRI field, parallel imaging saw widespread development and application following the introduction of the SiMultaneous Acquisition of Spatial Harmonics (SMASH) technique in 1996–7. The SENSitivity Encoding (SENSE) and Generalized Autocalibrating Partially Parallel Acquisitions (GRAPPA) techniques are the parallel imaging methods in most common use today. The advent of parallel MRI resulted in extensive research and development in image reconstruction and RF coil design, as well as in a rapid expansion of the number of receiver channels available on commercial MR systems. Parallel MRI is now used routinely for MRI examinations in a wide range of body areas and clinical or research applications.

Quantitative MRI

Most MRI focuses on qualitative interpretation of MR data by acquiring spatial maps of relative variations in signal strength which are "weighted" by certain parameters. Quantitative methods instead attempt to determine spatial maps of accurate tissue relaxometry parameter values or magnetic field, or to measure the size of certain spatial features.

Examples of quantitative MRI methods are:

- T1-mapping (notably used in cardiac magnetic resonance imaging)

- T2-mapping

- Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM)

- Quantitative fluid flow MRI (i.e. some cerebrospinal fluid flow MRI)

- Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE)

Quantitative MRI aims to increase the reproducibility of MR images and interpretations, but has historically require longer scan times.

Quantitative MRI (or qMRI) sometimes more specifically refers to multi-parametric quantitative MRI, the mapping of multiple tissue relaxometry parameters in a single imaging session. Efforts to make multi-parametric quantitative MRI faster have produced sequences which map multiple parameters simultaneously, either by building separate encoding methods for each parameter into the sequence, or by fitting MR signal evolution to a multi-parameter model.

Hyperpolarized gas MRI

Main article: Hyperpolarized gas MRITraditional MRI generates poor images of lung tissue because there are fewer water molecules with protons that can be excited by the magnetic field. Using hyperpolarized gas an MRI scan can identify ventilation defects in the lungs. Before the scan, a patient is asked to inhale hyperpolarized xenon mixed with a buffer gas of helium or nitrogen. The resulting lung images are much higher quality than with traditional MRI.

Safety

Main article: Safety of magnetic resonance imagingMRI is, in general, a safe technique, although injuries may occur as a result of failed safety procedures or human error. Contraindications to MRI include most cochlear implants and cardiac pacemakers, shrapnel, and metallic foreign bodies in the eyes. Magnetic resonance imaging in pregnancy appears to be safe, at least during the second and third trimesters if done without contrast agents. Since MRI does not use any ionizing radiation, its use is generally favored in preference to CT when either modality could yield the same information. Some patients experience claustrophobia and may require sedation or shorter MRI protocols. Amplitude and rapid switching of gradient coils during image acquisition may cause peripheral nerve stimulation.

| External videos | |

|---|---|

MRI uses powerful magnets and can therefore cause magnetic materials to move at great speeds, posing a projectile risk, and may cause fatal accidents. However, as millions of MRIs are performed globally each year, fatalities are extremely rare.

MRI machines can produce loud noise, up to 120 dB(A). This can cause hearing loss, tinnitus and hyperacusis, so appropriate hearing protection is essential for anyone inside the MRI scanner room during the examination.

Overuse

See also: OverdiagnosisMedical societies issue guidelines for when physicians should use MRI on patients and recommend against overuse. MRI can detect health problems or confirm a diagnosis, but medical societies often recommend that MRI not be the first procedure for creating a plan to diagnose or manage a patient's complaint. A common case is to use MRI to seek a cause of low back pain; the American College of Physicians, for example, recommends against imaging (including MRI) as unlikely to result in a positive outcome for the patient.

Artifacts

Main article: MRI artifact

An MRI artifact is a visual artifact, that is, an anomaly during visual representation. Many different artifacts can occur during magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), some affecting the diagnostic quality, while others may be confused with pathology. Artifacts can be classified as patient-related, signal processing-dependent and hardware (machine)-related.

Non-medical use

Main article: Nuclear magnetic resonance § ApplicationsMRI is used industrially mainly for routine analysis of chemicals. The nuclear magnetic resonance technique is also used, for example, to measure the ratio between water and fat in foods, monitoring of flow of corrosive fluids in pipes, or to study molecular structures such as catalysts.

Being non-invasive and non-damaging, MRI can be used to study the anatomy of plants, their water transportation processes and water balance. It is also applied to veterinary radiology for diagnostic purposes. Outside this, its use in zoology is limited due to the high cost; but it can be used on many species.

In palaeontology it is used to examine the structure of fossils.

Forensic imaging provides graphic documentation of an autopsy, which manual autopsy does not. CT scanning provides quick whole-body imaging of skeletal and parenchymal alterations, whereas MR imaging gives better representation of soft tissue pathology. All that being said, MRI is more expensive, and more time-consuming to utilize. Moreover, the quality of MR imaging deteriorates below 10 °C.

History

Main article: History of magnetic resonance imagingIn 1971 at Stony Brook University, Paul Lauterbur applied magnetic field gradients in all three dimensions and a back-projection technique to create NMR images. He published the first images of two tubes of water in 1973 in the journal Nature, followed by the picture of a living animal, a clam, and in 1974 by the image of the thoracic cavity of a mouse. Lauterbur called his imaging method zeugmatography, a term which was replaced by (N)MR imaging. In the late 1970s, physicists Peter Mansfield and Paul Lauterbur developed MRI-related techniques, like the echo-planar imaging (EPI) technique.

Raymond Damadian's work into nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) has been incorporated into MRI, having built one of the first scanners.

Advances in semiconductor technology were crucial to the development of practical MRI, which requires a large amount of computational power. This was made possible by the rapidly increasing number of transistors on a single integrated circuit chip. Mansfield and Lauterbur were awarded the 2003 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their "discoveries concerning magnetic resonance imaging".

See also

- Amplified magnetic resonance imaging

- Cerebrospinal fluid flow MRI

- Electron paramagnetic resonance

- High-definition fiber tracking

- High-resolution computed tomography

- History of neuroimaging

- International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine

- Jemris

- List of neuroimaging software

- Magnetic immunoassay

- Magnetic particle imaging

- Magnetic resonance elastography

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (journal)

- Magnetic resonance microscopy

- Nobel Prize controversies – Physiology or medicine

- Rabi cycle

- Robinson oscillator

- Sodium MRI

- Virtopsy

References

- ^ Rinck, Peter A. (2024). Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. A critical introduction. e-Textbook (14th ed.). TRTF – The Round Table Foundation: TwinTree Media. "Magnetic Resonance in Medicine". www.magnetic-resonance.org.

- McRobbie DW, Moore EA, Graves MJ, Prince MR (2007). MRI from Picture to Proton. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-139-45719-4.

- ^ Hoult DI, Bahkar B (1998). "NMR Signal Reception: Virtual Photons and Coherent Spontaneous Emission". Concepts in Magnetic Resonance. 9 (5): 277–297. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0534(1997)9:5<277::AID-CMR1>3.0.CO;2-W.

- Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Johnson E, Lee C, Feigelson HS, Flynn M, et al. (June 2012). "Use of diagnostic imaging studies and associated radiation exposure for patients enrolled in large integrated health care systems, 1996-2010". JAMA. 307 (22): 2400–9. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.5960. PMC 3859870. PMID 22692172.

- Health at a glance 2009 OECD indicators. 2009. doi:10.1787/health_glance-2009-en. ISBN 978-92-64-07555-9.

- ^ McRobbie DW (2007). MRI from picture to proton. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68384-5.

- "National Cancer Institute". Cancer.gov. Retrieved 2024-09-16.

- "Tesla Engineering Ltd - Magnet Division - MRI Supercon". www.tesla.co.uk. Retrieved 2022-08-16.

- Qiuliang, Wang (January 2022). "Successful Development of a 9.4T/800mm Whole-body MRI Superconducting Magnet at IEE CAS" (PDF). snf.ieeecsc.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on Mar 22, 2023.

- Nowogrodzki, Anna (2018-10-31). "The world's strongest MRI machines are pushing human imaging to new limits". Nature. 563 (7729): 24–26. Bibcode:2018Natur.563...24N. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-07182-7. PMID 30382222. S2CID 53153608.

- CEA (2021-10-07). "The most powerful MRI scanner in the world delivers its first images!". CEA/English Portal. Retrieved 2022-08-16.

- Budinger, Thomas F.; Bird, Mark D. (2018-03-01). "MRI and MRS of the human brain at magnetic fields of 14T to 20T: Technical feasibility, safety, and neuroscience horizons". NeuroImage. Neuroimaging with Ultra-high Field MRI: Present and Future. 168: 509–531. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.01.067. ISSN 1053-8119. PMID 28179167. S2CID 4054160.

- Li, Yi; Roell, Stefan (2021-12-01). "Key designs of a short-bore and cryogen-free high temperature superconducting magnet system for 14 T whole-body MRI". Superconductor Science and Technology. 34 (12): 125005. Bibcode:2021SuScT..34l5005L. doi:10.1088/1361-6668/ac2ec8. ISSN 0953-2048. S2CID 242194782.

- Sasaki M, Ehara S, Nakasato T, Tamakawa Y, Kuboya Y, Sugisawa M, Sato T (April 1990). "MR of the shoulder with a 0.2-T permanent-magnet unit". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 154 (4): 777–8. doi:10.2214/ajr.154.4.2107675. PMID 2107675.

- "Guildford company gets FDA approval for bedside MRI". New Haven Register. 12 February 2020. Archived from the original on 3 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- McDermott R, Lee S, ten Haken B, Trabesinger AH, Pines A, Clarke J (May 2004). "Microtesla MRI with a superconducting quantum interference device". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (21): 7857–61. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.7857M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0402382101. PMC 419521. PMID 15141077.

- Zotev VS, Matlashov AN, Volegov PL, Urbaitis AV, Espy MA, Kraus RH (2007). "SQUID-based instrumentation for ultralow-field MRI". Superconductor Science and Technology. 20 (11): S367–73. arXiv:0705.0661. Bibcode:2007SuScT..20S.367Z. doi:10.1088/0953-2048/20/11/S13. S2CID 119160258.

- Vesanen PT, Nieminen JO, Zevenhoven KC, Dabek J, Parkkonen LT, Zhdanov AV, et al. (June 2013). "Hybrid ultra-low-field MRI and magnetoencephalography system based on a commercial whole-head neuromagnetometer". Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 69 (6): 1795–804. doi:10.1002/mrm.24413. PMID 22807201. S2CID 40026232.

- De Leon-Rodriguez, L.M. (2015). "Basic MR Relaxation Mechanisms and Contrast Agent Design". Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 42 (3): 545–565. doi:10.1002/jmri.24787. PMC 4537356. PMID 25975847.

- "T1 relaxation experiment" (PDF).

- McHale, J. (2017). Molecular Spectroscopy. CRC Press/Taylor and Francis Group. pp. 73–80.

- ^ "Magnetic Resonance Imaging". University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original on 2017-05-10. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ^ Johnson KA. "Basic proton MR imaging. Tissue Signal Characteristics".

- ^ Patil T (2013-01-18). "MRI sequences". Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- "Magnetic Resonance, a critical peer-reviewed introduction". European Magnetic Resonance Forum. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Consumer Reports; American College of Physicians. "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF). Choosing Wisely. presented by ABIM Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ Consumer Reports; American College of Physicians (April 2012). "Imaging tests for lower-back pain: Why you probably don't need them" (PDF). High Value Care. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2013. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- Husband J (2008). Recommendations for Cross-Sectional Imaging in Cancer Management: Computed Tomography – CT Magnetic Resonance Imaging – MRI Positron Emission Tomography – PET-CT (PDF). Royal College of Radiologists. ISBN 978-1-905034-13-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-07. Retrieved 2014-05-29.

- Heavey S, Costa H, Pye H, Burt EC, Jenkinson S, Lewis GR, et al. (May 2019). "PEOPLE: PatiEnt prOstate samPLes for rEsearch, a tissue collection pathway utilizing magnetic resonance imaging data to target tumor and benign tissue in fresh radical prostatectomy specimens". The Prostate. 79 (7): 768–777. doi:10.1002/pros.23782. PMC 6618051. PMID 30807665.

- Heavey S, Haider A, Sridhar A, Pye H, Shaw G, Freeman A, Whitaker H (October 2019). "Use of Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Biopsy Data to Guide Sampling Procedures for Prostate Cancer Biobanking". Journal of Visualized Experiments (152). doi:10.3791/60216. PMID 31657791.

- American Society of Neuroradiology (2013). "ACR-ASNR Practice Guideline for the Performance and Interpretation of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Brain" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-12. Retrieved 2013-11-10.

- Rowayda AS (May 2012). "An improved MRI segmentation for atrophy assessment". International Journal of Computer Science Issues (IJCSI). 9 (3).

- Rowayda AS (February 2013). "Regional atrophy analysis of MRI for early detection of alzheimer's disease". International Journal of Signal Processing, Image Processing and Pattern Recognition. 6 (1): 49–53.

- Nolen-Hoeksema S (2014). Abnormal Psychology (Sixth ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. p. 67.

- Brown RA, Nelson JA (June 2016). "The Invention and Early History of the N-Localizer for Stereotactic Neurosurgery". Cureus. 8 (6): e642. doi:10.7759/cureus.642. PMC 4959822. PMID 27462476.

- Leksell L, Leksell D, Schwebel J (January 1985). "Stereotaxis and nuclear magnetic resonance". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 48 (1): 14–8. doi:10.1136/jnnp.48.1.14. PMC 1028176. PMID 3882889.

- Heilbrun MP, Sunderland PM, McDonald PR, Wells TH, Cosman E, Ganz E (1987). "Brown-Roberts-Wells stereotactic frame modifications to accomplish magnetic resonance imaging guidance in three planes". Applied Neurophysiology. 50 (1–6): 143–52. doi:10.1159/000100700. PMID 3329837.

- Kanemaru, Noriko; Takao, Hidemasa; Amemiya, Shiori; Abe, Osamu (2 December 2021). "The effect of a post-scan processing denoising system on image quality and morphometric analysis". Journal of Neuroradiology. 49 (2): 205–212. doi:10.1016/j.neurad.2021.11.007. PMID 34863809. S2CID 244907903.

- "100-Hour-Long MRI of Human Brain Produces Most Detailed 3D Images Yet". 10 July 2019.

- "Team publishes on highest resolution brain MRI scan".

- ^ Peterson, Bradley S.; Trampush, Joey; Maglione, Margaret; Bolshakova, Maria; Brown, Morah; Rozelle, Mary; Motala, Aneesa; Yagyu, Sachi; Miles, Jeremy; Pakdaman, Sheila; Gastelum, Mario; Nguyen, Bich Thuy (Becky); Tokutomi, Erin; Lee, Esther; Belay, Jerusalem Z.; Schaefer, Coleman; Coughlin, Benjamin; Celosse, Karin; Molakalapalli, Sreya; Shaw, Brittany; Sazmin, Tanzina; Onyekwuluje, Anne N.; Tolentino, Danica; Hempel, Susanne (2024). "ADHD Diagnosis and Treatment in Children and Adolescents". effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov. doi:10.23970/ahrqepccer267. PMID 38657097. Retrieved 2024-06-19.

- Petersen SE, Aung N, Sanghvi MM, Zemrak F, Fung K, Paiva JM, et al. (February 2017). "Reference ranges for cardiac structure and function using cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) in Caucasians from the UK Biobank population cohort". Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 19 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 18. doi:10.1186/s12968-017-0327-9. PMC 5304550. PMID 28178995.

- American College of Radiology; Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography; Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance; American Society of Nuclear Cardiology; North American Society for Cardiac Imaging; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography Interventions; Society of Interventional Radiology (October 2006). "ACCF/ACR/SCCT/SCMR/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SIR 2006 appropriateness criteria for cardiac computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Quality Strategic Directions Committee Appropriateness Criteria Working Group". Journal of the American College of Radiology. 3 (10): 751–71. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2006.08.008. PMID 17412166.

- Helms C (2008). Musculoskeletal MRI. Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-5534-1.

- Aivazoglou, LU; Guimarães, JB; Link, TM; Costa, MAF; Cardoso, FN; de Mattos Lombardi Badia, B; Farias, IB; de Rezende Pinto, WBV; de Souza, PVS; Oliveira, ASB; de Siqueira Carvalho, AA; Aihara, AY; da Rocha Corrêa Fernandes, A (21 April 2021). "MR imaging of inherited myopathies: a review and proposal of imaging algorithms". European Radiology. 31 (11): 8498–8512. doi:10.1007/s00330-021-07931-9. PMID 33881569. S2CID 233314102.

- Schmidt GP, Reiser MF, Baur-Melnyk A (December 2007). "Whole-body imaging of the musculoskeletal system: the value of MR imaging". Skeletal Radiology. 36 (12). Springer Nature: 1109–19. doi:10.1007/s00256-007-0323-5. PMC 2042033. PMID 17554538.

- Havsteen I, Ohlhues A, Madsen KH, Nybing JD, Christensen H, Christensen A (2017). "Are Movement Artifacts in Magnetic Resonance Imaging a Real Problem?-A Narrative Review". Frontiers in Neurology. 8: 232. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00232. PMC 5447676. PMID 28611728.

- Taber, K H; Herrick, R C; Weathers, S W; Kumar, A J; Schomer, D F; Hayman, L A (November 1998). "Pitfalls and artifacts encountered in clinical MR imaging of the spine". RadioGraphics. 18 (6): 1499–1521. doi:10.1148/radiographics.18.6.9821197. ISSN 0271-5333. PMID 9821197.

- Frydrychowicz A, Lubner MG, Brown JJ, Merkle EM, Nagle SK, Rofsky NM, Reeder SB (March 2012). "Hepatobiliary MR imaging with gadolinium-based contrast agents". Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 35 (3): 492–511. doi:10.1002/jmri.22833. PMC 3281562. PMID 22334493.

- Sandrasegaran K, Lin C, Akisik FM, Tann M (July 2010). "State-of-the-art pancreatic MRI". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 195 (1): 42–53. doi:10.2214/ajr.195.3_supplement.0s42. PMID 20566796.

- Masselli G, Gualdi G (August 2012). "MR imaging of the small bowel". Radiology. 264 (2): 333–48. doi:10.1148/radiol.12111658. PMID 22821694.

- Zijta FM, Bipat S, Stoker J (May 2010). "Magnetic resonance (MR) colonography in the detection of colorectal lesions: a systematic review of prospective studies". European Radiology. 20 (5): 1031–46. doi:10.1007/s00330-009-1663-4. PMC 2850516. PMID 19936754.

- Wheaton AJ, Miyazaki M (August 2012). "Non-contrast enhanced MR angiography: physical principles". Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 36 (2). Wiley: 286–304. doi:10.1002/jmri.23641. PMID 22807222. S2CID 24048799.

- Haacke EM, Brown RF, Thompson M, Venkatesan R (1999). Magnetic resonance imaging: Physical principles and sequence design. New York: J. Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-35128-3.

- Rinck PA (2014). "Chapter 13: Contrast Agents". Magnetic Resonance in Medicine.

- Murphy KJ, Brunberg JA, Cohan RH (October 1996). "Adverse reactions to gadolinium contrast media: a review of 36 cases". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 167 (4): 847–9. doi:10.2214/ajr.167.4.8819369. PMID 8819369.

- "ACR guideline". guideline.gov. 2005. Archived from the original on 2006-09-29. Retrieved 2006-11-22.

- Shugaev, Sergey; Caravan, Peter (2021). "Metal Ions in Bio-imaging Techniques: A Short Overview". In Sigel, Astrid; Freisinger, Eva; Sigel, Roland K.O. (eds.). Metal Ions in Bio-Imaging Techniques. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1–37. doi:10.1515/9783110685701-007. ISBN 978-3-11-068570-1.

- "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns that gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) are retained in the body; requires new class warnings". USA FDA. 2018-05-16.

- Thomsen HS, Morcos SK, Dawson P (November 2006). "Is there a causal relation between the administration of gadolinium based contrast media and the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF)?". Clinical Radiology. 61 (11): 905–6. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2006.09.003. PMID 17018301.

- "FDA Drug Safety Communication: New warnings for using gadolinium-based contrast agents in patients with kidney dysfunction". Information on Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 23 December 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- "FDA Public Health Advisory: Gadolinium-containing Contrast Agents for Magnetic Resonance Imaging". fda.gov. Archived from the original on 2006-09-28.

- "Gadolinium-containing contrast agents: new advice to minimise the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis". Drug Safety Update. 3 (6): 3. January 2010.

- "MRI Questions and Answers" (PDF). Concord, CA: International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- "Response to the FDA's May 23, 2007, Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis Update1 — Radiology". Radiological Society of North America. 2007-09-12. Archived from the original on 2012-07-19. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- Jones J, Gaillard F. "MRI sequences (overview)". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- ^ "Magnetic Resonance Imaging". University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original on 2017-05-10. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ^ Johnson KA. "Basic proton MR imaging. Tissue Signal Characteristics". Harvard Medical School. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- Henkelman, RM; Hardy, PA; Bishop, JE; Poon, CS; Plewes, DB (September 1992). "Why fat is bright in RARE and fast spin-echo imaging". Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2 (5): 533–40. doi:10.1002/jmri.1880020511. PMID 1392246.

- Graham D, Cloke P, Vosper M (2011-05-31). Principles and Applications of Radiological Physics E-Book (6 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-7020-4614-8.}

- du Plessis V, Jones J. "MRI sequences (overview)". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2017-01-13.

- Lefevre N, Naouri JF, Herman S, Gerometta A, Klouche S, Bohu Y (2016). "A Current Review of the Meniscus Imaging: Proposition of a Useful Tool for Its Radiologic Analysis". Radiology Research and Practice. 2016: 8329296. doi:10.1155/2016/8329296. PMC 4766355. PMID 27057352.

- ^ Luijkx T, Weerakkody Y. "Steady-state free precession MRI". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2017-10-13.

- ^ Chavhan GB, Babyn PS, Thomas B, Shroff MM, Haacke EM (2009). "Principles, techniques, and applications of T2*-based MR imaging and its special applications". Radiographics. 29 (5): 1433–49. doi:10.1148/rg.295095034. PMC 2799958. PMID 19755604.

- ^ Di Muzio B, Gaillard F. "Susceptibility weighted imaging". Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- Sharma R, Taghi Niknejad M. "Short tau inversion recovery". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2017-10-13.

- Berger F, de Jonge M, Smithuis R, Maas M. "Stress fractures". Radiology Assistant. Radiology Society of the Netherlands. Retrieved 2017-10-13.

- Hacking C, Taghi Niknejad M, et al. "Fluid attenuation inversion recoveryg". radiopaedia.org. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

- ^ Di Muzio B, Abd Rabou A. "Double inversion recovery sequence". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2017-10-13.

- Lee M, Bashir U. "Diffusion weighted imaging". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2017-10-13.

- Weerakkody Y, Gaillard F. "Ischaemic stroke". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- Hammer M. "MRI Physics: Diffusion-Weighted Imaging". XRayPhysics. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- An H, Ford AL, Vo K, Powers WJ, Lee JM, Lin W (May 2011). "Signal evolution and infarction risk for apparent diffusion coefficient lesions in acute ischemic stroke are both time- and perfusion-dependent". Stroke. 42 (5): 1276–81. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.610501. PMC 3384724. PMID 21454821.

- ^ Smith D, Bashir U. "Diffusion tensor imaging". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2017-10-13.

- Chua TC, Wen W, Slavin MJ, Sachdev PS (February 2008). "Diffusion tensor imaging in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: a review". Current Opinion in Neurology. 21 (1): 83–92. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282f4594b. PMID 18180656. S2CID 24731783.

- Gaillard F. "Dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) MR perfusion". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2017-10-14.

- Chen F, Ni YC (March 2012). "Magnetic resonance diffusion-perfusion mismatch in acute ischemic stroke: An update". World Journal of Radiology. 4 (3): 63–74. doi:10.4329/wjr.v4.i3.63. PMC 3314930. PMID 22468186.

- "Arterial spin labeling". University of Michigan. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- Gaillard F. "Arterial spin labelling (ASL) MR perfusion". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- Gaillard F. "Dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) MR perfusion". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- Turnbull LW (January 2009). "Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in the diagnosis and management of breast cancer". NMR in Biomedicine. 22 (1): 28–39. doi:10.1002/nbm.1273. PMID 18654999. S2CID 5305422.

- Chou Ih. "Milestone 19: (1990) Functional MRI". Nature. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- Luijkx T, Gaillard F. "Functional MRI". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- ^ "Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA)". Johns Hopkins Hospital. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- Keshavamurthy J, Ballinger R et al. "Phase contrast imaging". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- Landheer K, Schulte RF, Treacy MS, Swanberg KM, Juchem C (April 2020). "Theoretical description of modern H in Vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopic pulse sequences". Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 51 (4): 1008–1029. doi:10.1002/jmri.26846. PMID 31273880. S2CID 195806833.

- Rosen Y, Lenkinski RE (July 2007). "Recent advances in magnetic resonance neurospectroscopy". Neurotherapeutics. 4 (3): 330–45. doi:10.1016/j.nurt.2007.04.009. PMC 7479727. PMID 17599700.

- Golder W (June 2004). "Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in clinical oncology". Onkologie. 27 (3): 304–9. doi:10.1159/000077983. PMID 15249722. S2CID 20644834.

- Chakeres DW, Abduljalil AM, Novak P, Novak V (2002). "Comparison of 1.5 and 8 tesla high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging of lacunar infarcts". Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 26 (4): 628–32. doi:10.1097/00004728-200207000-00027. PMID 12218832. S2CID 32536398.

- "MRI-scanner van 7 miljoen in gebruik" [MRI scanner of €7 million in use] (in Dutch). Medisch Contact. December 5, 2007.

- Abeida H, Zhang Q, Li J, Merabtine N (2013). "Iterative Sparse Asymptotic Minimum Variance Based Approaches for Array Processing". IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing. 61 (4): 933–44. arXiv:1802.03070. Bibcode:2013ITSP...61..933A. doi:10.1109/tsp.2012.2231676. S2CID 16276001.

- S Zhang, M Uecker, D Voit, KD Merboldt, J Frahm (2010a) Real-time cardiovascular magnetic resonance at high temporal resolution: radial FLASH with nonlinear inverse reconstruction. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 12, 39, doi:10.1186/1532-429X-12-39

- M Uecker, S Zhang, D Voit, A Karaus, KD Merboldt, J Frahm (2010a) Real-time MRI at a resolution of 20 ms. NMR Biomed 23: 986-994, doi:10.1002/nbm.1585

- ^ Uyanik I, Lindner P, Tsiamyrtzis P, Shah D, Tsekos NV, Pavlidis IT (2013). "Applying a Level Set Method for Resolving Physiologic Motions in Free-Breathing and Non-gated Cardiac MRI". Functional Imaging and Modeling of the Heart. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 7945. pp. 466–473. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-38899-6_55. ISBN 978-3-642-38898-9. ISSN 0302-9743. S2CID 16840737.

- Lewin JS (May 1999). "Interventional MR imaging: concepts, systems, and applications in neuroradiology". AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 20 (5): 735–48. PMC 7056143. PMID 10369339.

- Sisk JE (2013). The Gale Encyclopedia of Nursing and Allied Health (3rd ed.). Farmington, MI: Gale. ISBN 9781414498881 – via Credo Reference.

- Cline HE, Schenck JF, Hynynen K, Watkins RD, Souza SP, Jolesz FA (1992). "MR-guided focused ultrasound surgery". Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 16 (6): 956–65. doi:10.1097/00004728-199211000-00024. PMID 1430448. S2CID 11944489.

- Gore JC, Yankeelov TE, Peterson TE, Avison MJ (June 2009). "Molecular imaging without radiopharmaceuticals?". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 50 (6). Society of Nuclear Medicine: 999–1007. doi:10.2967/jnumed.108.059576. PMC 2719757. PMID 19443583.

- "Hyperpolarized Noble Gas MRI Laboratory: Hyperpolarized Xenon MR Imaging of the Brain". Harvard Medical School. Archived from the original on 2018-09-20. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- Hurd RE, John BK (1991). "Gradient-enhanced proton-detected heteronuclear multiple-quantum coherence spectroscopy". Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 91 (3): 648–53. Bibcode:1991JMagR..91..648H. doi:10.1016/0022-2364(91)90395-a.

- Brown RA, Venters RA, Tang PP, Spicer LD (1995). "A Test for Scaler Coupling between Heteronuclei Using Gradient-Enhanced Proton-Detected HMQC Spectroscopy". Journal of Magnetic Resonance, Series A. 113 (1): 117–19. Bibcode:1995JMagR.113..117B. doi:10.1006/jmra.1995.1064.

- Miller AF, Egan LA, Townsend CA (March 1997). "Measurement of the degree of coupled isotopic enrichment of different positions in an antibiotic peptide by NMR". Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 125 (1): 120–31. Bibcode:1997JMagR.125..120M. doi:10.1006/jmre.1997.1107. PMID 9245367. S2CID 14022996.

- Necus J, Sinha N, Smith FE, Thelwall PE, Flowers CJ, Taylor PN, et al. (June 2019). "White matter microstructural properties in bipolar disorder in relationship to the spatial distribution of lithium in the brain". Journal of Affective Disorders. 253: 224–231. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.075. PMC 6609924. PMID 31054448.

- Gallagher FA (July 2010). "An introduction to functional and molecular imaging with MRI". Clinical Radiology. 65 (7): 557–66. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2010.04.006. PMID 20541655.

- Xue S, Qiao J, Pu F, Cameron M, Yang JJ (2013). "Design of a novel class of protein-based magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents for the molecular imaging of cancer biomarkers". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology. 5 (2): 163–79. doi:10.1002/wnan.1205. PMC 4011496. PMID 23335551.

- Liu CH, Kim YR, Ren JQ, Eichler F, Rosen BR, Liu PK (January 2007). "Imaging cerebral gene transcripts in live animals". The Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (3): 713–22. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4660-06.2007. PMC 2647966. PMID 17234603.

- Liu CH, Ren J, Liu CM, Liu PK (January 2014). "Intracellular gene transcription factor protein-guided MRI by DNA aptamers in vivo". FASEB Journal. 28 (1): 464–73. doi:10.1096/fj.13-234229. PMC 3868842. PMID 24115049.

- Liu CH, You Z, Liu CM, Kim YR, Whalen MJ, Rosen BR, Liu PK (March 2009). "Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging reversal by gene knockdown of matrix metalloproteinase-9 activities in live animal brains". The Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (11): 3508–17. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5332-08.2009. PMC 2726707. PMID 19295156.

- Liu CH, Yang J, Ren JQ, Liu CM, You Z, Liu PK (February 2013). "MRI reveals differential effects of amphetamine exposure on neuroglia in vivo". FASEB Journal. 27 (2): 712–24. doi:10.1096/fj.12-220061. PMC 3545538. PMID 23150521.

- Sodickson DK, Manning WJ (October 1997). "Simultaneous acquisition of spatial harmonics (SMASH): fast imaging with radiofrequency coil arrays". Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 38 (4): 591–603. doi:10.1002/mrm.1910380414. PMID 9324327. S2CID 17505246.

- Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P (November 1999). "SENSE: sensitivity encoding for fast MRI". Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 42 (5): 952–62. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1522-2594(199911)42:5<952::AID-MRM16>3.0.CO;2-S. PMID 10542355. S2CID 16046989.

- Griswold MA, Jakob PM, Heidemann RM, Nittka M, Jellus V, Wang J, Kiefer B, Haase A (June 2002). "Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA)". Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 47 (6): 1202–10. doi:10.1002/mrm.10171. PMID 12111967. S2CID 14724155.

- ^ Gulani, Vikas & Nicole, Sieberlich (2020). "Quantitative MRI: Rationale and Challenges". Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Academic Press. p. xxxvii-li. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-817057-1.00001-9. ISBN 9780128170571. S2CID 234995365.

- Captur, G; Manisty, C; Moon, JC (2016). "Cardiac MRI evaluation of myocardial disease". Heart. 102 (18): 1429–35. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-309077. PMID 27354273. S2CID 23647168.

- Cobianchi Bellisari, F; De Marino, L; Arrigoni, F; Mariani, S; Bruno, F; Palumbo, P; et al. (2021). "T2-mapping MRI evaluation of patellofemoral cartilage in patients submitted to intra-articular platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections". Radiol Med. 126 (8): 1085–1094. doi:10.1007/s11547-021-01372-6. PMC 8292236. PMID 34008045.

- Gaillard, Frank; Knipe, Henry (13 Oct 2021). "CSF flow studies | Radiology Reference Article". Radiopaedia. doi:10.53347/rID-37401. Retrieved 2021-11-24.

- Hirsch, Sebastian; Braun, Jürgen; Sack, Ingolf (2016). Magnetic Resonance Elastography | Wiley Online Books. doi:10.1002/9783527696017. ISBN 9783527696017. Archived from the original on 2022-03-05. Retrieved 2022-03-06.

- Seiler A, Nöth U, Hok P, Reiländer A, Maiworm M, Baudrexel S; et al. (2021). "Multiparametric Quantitative MRI in Neurological Diseases". Front Neurol. 12: 640239. doi:10.3389/fneur.2021.640239. PMC 7982527. PMID 33763021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Warntjes JB, Leinhard OD, West J, Lundberg P (2008). "Rapid magnetic resonance quantification on the brain: Optimization for clinical usage". Magn Reson Med. 60 (2): 320–9. doi:10.1002/mrm.21635. PMID 18666127. S2CID 11617224.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ehses P, Seiberlich N, Ma D, Breuer FA, Jakob PM, Griswold MA; et al. (2013). "IR TrueFISP with a golden-ratio-based radial readout: fast quantification of T1, T2, and proton density". Magn Reson Med. 69 (1): 71–81. doi:10.1002/mrm.24225. PMID 22378141. S2CID 24244167.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ma D, Gulani V, Seiberlich N, Liu K, Sunshine JL, Duerk JL; et al. (2013). "Magnetic resonance fingerprinting". Nature. 495 (7440): 187–92. Bibcode:2013Natur.495..187M. doi:10.1038/nature11971. PMC 3602925. PMID 23486058.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Watson RE (2015). "Lessons Learned from MRI Safety Events". Current Radiology Reports. 3 (10). doi:10.1007/s40134-015-0122-z. S2CID 57880401.

- Mervak BM, Altun E, McGinty KA, Hyslop WB, Semelka RC, Burke LM (March 2019). "MRI in pregnancy: Indications and practical considerations". Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 49 (3): 621–631. doi:10.1002/jmri.26317. PMID 30701610. S2CID 73412175.

- "iRefer". Royal College of Radiologists. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- Murphy KJ, Brunberg JA (1997). "Adult claustrophobia, anxiety and sedation in MRI". Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 15 (1). Elsevier BV: 51–4. doi:10.1016/s0730-725x(96)00351-7. PMID 9084025.

- Shahrouki, Puja; Nguyen, Kim-Lien; Moriarty, John M.; Plotnik, Adam N.; Yoshida, Takegawa; Finn, J. Paul (2021-09-01). "Minimizing table time in patients with claustrophobia using focused ferumoxytol-enhanced MR angiography ( f -FEMRA): a feasibility study". The British Journal of Radiology. 94 (1125): 20210430. doi:10.1259/bjr.20210430. ISSN 0007-1285. PMC 9327752. PMID 34415199.

- Klein V, Davids M, Schad LR, Wald LL, Guérin B (February 2021). "Investigating cardiac stimulation limits of MRI gradient coils using electromagnetic and electrophysiological simulations in human and canine body models". Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 85 (2): 1047–1061. doi:10.1002/mrm.28472. PMC 7722025. PMID 32812280.

- Agence France-Presse (30 January 2018). "Man dies after being sucked into MRI scanner at Indian hospital". The Guardian.

- "Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Exams per 1,000 Population, 2014". OECD. 2016.

- Mansouri M, Aran S, Harvey HB, Shaqdan KW, Abujudeh HH (April 2016). "Rates of safety incident reporting in MRI in a large academic medical center". Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 43 (4). John Wiley and Sons: 998–1007. doi:10.1002/jmri.25055. PMID 26483127. S2CID 25245904.

- Price, D. L.; De Wilde, J. P.; Papadaki, A. M.; Curran, J. S.; Kitney, R. I. (February 2001). "Investigation of acoustic noise on 15 MRI scanners from 0.2 T to 3 T". Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 13 (2): 288–293. doi:10.1002/1522-2586(200102)13:2<288::aid-jmri1041>3.0.co;2-p. ISSN 1053-1807. PMID 11169836. S2CID 20684100.

- ^ Erasmus LJ, Hurter D, Naude M, Kritzinger HG, Acho S (2004). "A short overview of MRI artefacts". South African Journal of Radiology. 8 (2): 13. doi:10.4102/sajr.v8i2.127.

- Van As H (2006-11-30). "Intact plant MRI for the study of cell water relations, membrane permeability, cell-to-cell and long distance water transport". Journal of Experimental Botany. 58 (4). Oxford University Press (OUP): 743–56. doi:10.1093/jxb/erl157. PMID 17175554.

- Ziegler A, Kunth M, Mueller S, Bock C, Pohmann R, Schröder L, Faber C, Giribet G (2011-10-13). "Application of magnetic resonance imaging in zoology". Zoomorphology. 130 (4). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 227–254. doi:10.1007/s00435-011-0138-8. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0013-B8B0-B. ISSN 0720-213X. S2CID 43555012.

- Giovannetti G, Guerrini A, Salvadori PA (July 2016). "Magnetic resonance spectroscopy and imaging for the study of fossils". Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 34 (6). Elsevier BV: 730–742. doi:10.1016/j.mri.2016.03.010. PMID 26979538.

- ^ Filograna L, Pugliese L, Muto M, Tatulli D, Guglielmi G, Thali MJ, Floris R (February 2019). "A Practical Guide to Virtual Autopsy: Why, When and How". Seminars in Ultrasound, CT, and MR. 40 (1): 56–66. doi:10.1053/j.sult.2018.10.011. PMID 30686369. S2CID 59304740.

- Ruder TD, Thali MJ, Hatch GM (April 2014). "Essentials of forensic post-mortem MR imaging in adults". The British Journal of Radiology. 87 (1036): 20130567. doi:10.1259/bjr.20130567. PMC 4067017. PMID 24191122.

- LAUTERBUR, P. C. (1973). "Image Formation by Induced Local Interactions: Examples Employing Nuclear Magnetic Resonance". Nature. 242 (5394). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 190–191. Bibcode:1973Natur.242..190L. doi:10.1038/242190a0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4176060.

- Mansfield P, Grannell PK (1975). ""Diffraction" and microscopy in solids and liquids by NMR". Physical Review B. 12 (9): 3618–34. Bibcode:1975PhRvB..12.3618M. doi:10.1103/physrevb.12.3618.

- Sandomir, Richard (August 17, 2022). "Raymond Damadian, Creator of the First M.R.I. Scanner, Dies at 86". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- Rosenblum B, Kuttner F (2011). Quantum Enigma: Physics Encounters Consciousness. Oxford University Press. p. 127. ISBN 9780199792955.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2003". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 18 July 2007. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

Further reading

- Blümer P (1998). Blümler P, Blümich B, Botto RE, Fukushima E (eds.). Spatially Resolved Magnetic Resonance: Methods, Materials, Medicine, Biology, Rheology, Geology, Ecology, Hardware. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-29637-8.

- Blümich B, Kuhn W (1992). Magnetic Resonance Microscopy: Methods and Applications in Materials Science, Agriculture and Biomedicine. Wiley. ISBN 978-3-527-28403-0.

- Blümich B (2000). NMR Imaging of Materials. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850683-6.

- Eustace SJ, Nelson E (June 2004). "Whole body magnetic resonance imaging". BMJ. 328 (7453): 1387–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7453.1387. PMC 421763. PMID 15191954.

- Farhat IA, Belton P, Webb GA (2007). Magnetic Resonance in Food Science: From Molecules to Man. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-0-85404-340-8.

- Fukushima E (1989). NMR in Biomedicine: The Physical Basis. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-88318-609-1.

- Haacke EM, Brown RF, Thompson M, Venkatesan R (1999). Magnetic resonance imaging: Physical principles and sequence design. New York: J. Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-35128-3.

- Jin (1998). Electromagnetic Analysis and Design in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-9693-9.

- Kuperman V (2000). Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Physical Principles and Applications. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-053570-8.

- Lee SC, Kim K, Kim J, Lee S, Han Yi J, Kim SW, et al. (June 2001). "One micrometer resolution NMR microscopy". Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 150 (2): 207–13. Bibcode:2001JMagR.150..207L. doi:10.1006/jmre.2001.2319. PMID 11384182.

- Liang ZP, Lauterbur PC (1999). Principles of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Signal Processing Perspective. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-7803-4723-6.

- Mansfield P (1982). NMR Imaging in Biomedicine: Supplement 2 Advances in Magnetic Resonance. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-15406-2.

- Pykett IL (May 1982). "NMR imaging in medicine". Scientific American. 246 (5): 78–88. Bibcode:1982SciAm.246e..78P. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0582-78. PMID 7079720.

- Rinck PA (ed.). "The history of MRI". TRTF/EMRF.

- Sakr, HM; Fahmy, N; Elsayed, NS; Abdulhady, H; El-Sobky, TA; Saadawy, AM; Beroud, C; Udd, B (1 July 2021). "Whole-body muscle MRI characteristics of LAMA2-related congenital muscular dystrophy children: An emerging pattern". Neuromuscular Disorders. 31 (9): 814–823. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2021.06.012. PMID 34481707. S2CID 235691786.

- Schmitt F, Stehling MK, Turner R (1998). Echo-Planar Imaging: Theory, Technique and Application. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-540-63194-1.

- Simon M, Mattson JS (1996). The pioneers of NMR and magnetic resonance in medicine: The story of MRI. Ramat Gan, Israel: Bar-Ilan University Press. ISBN 978-0-9619243-1-7.

- Sprawls P (2000). Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Principles, Methods, and Techniques. Medical Physics Publishing. ISBN 978-0-944838-97-6.

External links

- Rinck PA (ed.). "MRI: A Peer-Reviewed, Critical Introduction". European Magnetic Resonance Forum (EMRF)/The Round Table Foundation (TRTF).

- A Guided Tour of MRI: An introduction for laypeople National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

- The Basics of MRI. Underlying physics and technical aspects.

- Video: What to Expect During Your MRI Exam from the Institute for Magnetic Resonance Safety, Education, and Research (IMRSER)

- Royal Institution Lecture – MRI: A Window on the Human Body

- A Short History of Magnetic Resonance Imaging from a European Point of View

- How MRI works explained simply using diagrams

- Real-time MRI videos: Biomedizinische NMR Forschungs GmbH.

- Paul C. Lauterbur, Genesis of the MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) notebook, September 1971 (all pages freely available for download in variety of formats from Science History Institute Digital Collections at digital.sciencehistory.org)

| Superconductivity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theories | |||||||||

| Characteristic parameters | |||||||||

| Phenomena | |||||||||

| Classification |

| ||||||||

| Technological applications | |||||||||

| List of superconductors | |||||||||

. Similarly, the time in which it takes for Mxy to return to zero is T2, with the rate

. Similarly, the time in which it takes for Mxy to return to zero is T2, with the rate  . Magnetization as a function of time is defined by the

. Magnetization as a function of time is defined by the