Talim (Kashmiri: تعليم, Kashmiri pronunciation: [t̪əːliːm], Urdu: تَعْلِیم, Arabic: تعليم, pronounced [taʕ.liːm] ) in textiles is a symbolic code and system of notation that facilitates the creation of intricate patterns in fabrics, such as shawls and carpets, and the written coded plans that include colour schemes and weaving instructions. The term is used in traditional hand-weaving in the Indian subcontinent. Talim was initially used to create certain types of patterns in Kashmiri shawls, and later came to be applied in the

production of carpets.

Etymology and origin

The term talim, which refers to a symbolic code and system of notation used by shawl and carpet artisans in their weaving processes, came to the Urdu language from the Arabic noun taʻlim (تعليم), which means "authoritative instruction", "teaching", or "edification". It means the same in Urdu and Kashmiri. The Arabic noun originated from the second form of the Arabic root verb ʻalima (علم), which means "to know".

According to a local belief in Kashmir, talim was introduced to them by Persian scholar and Sufi Muslim saint Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani. The belief notwithstanding, talim might have originated from Kashmir; Amritsar was the only place outside of Srinagar where talim was used, by migrated Kashmiri artisans.

Technique

Whereas carpets are generally woven horizontally, providing weavers with a clear view of the progress they are making in creating designs, in Kashmir, carpets are woven vertically, so the weaver is reliant on the talim.

The talim technique forms fabrics by passing the weft thread as per a given script that has design codes. Weavers use talim to weave the desired pattern with planned colours. Talim involves teamwork when applying the technique, as the process of creating intricate fabric designs in weaving begins with the Naqash (designer, who designs using pencils on graphs) meticulously crafting the design on a blank sheet of paper called a naska, and the master, Talim guru, making the colour codes and symbols for weft yarns that would interlace the warp to construct the desired design. He writes on a long strip of paper, in specific symbols, the colour codes, and the number of knots to be woven with each colour. Taraha guru collaborates with talim guru and is known as the artisan responsible for determining the colours. Talim uthana is a process or the act of "picking the codes" from the graph. A clerk called the Talim Navis would record the step-by-step instructions for these numbers and colours, and thousands of low-paid and interchangeable weavers would read or recite the record to carry out the design. Afterward, a talim copyist makes copies, which are needed when multiple looms weave the same product.

The script, which has been encoded, is deciphered and translated according to the specific guidelines of weavers in order to incorporate the design that is included within it. Talim has been compared to "hieroglyphics" or as a "notational-cum-cryptographic system", as it is challenging to decipher and is unique to the shawls of Kashmir, which requires expertise to comprehend. According to researcher Gagan Deep Kaur, "The talim is widely held to be a trade secret of the community and has always been fiercely guarded by the owners." Those who use talim for shawl-making do not assign important tasks to women, because of the fear that the technique and knowledge may be divulged to other communities when the women are sent there to be married.

The coded cards known as talim in the Kashmiri language were used for creating certain types of patterns in shawl weaving. The talim technique is employed in the creation of kani shawls, which originated from the Kanihama region of the Kashmir valley. Carpet weaving adapted the technique from shawl making. When Kashmiri artisans started to create carpets, they chose to continue using the talim rather than switching to a different method. The resurgence of the carpet industry in Amritsar during the last century resulted in the prevalent use of the talim technique among the local weavers, a majority of whom hailed from the region of Kashmir.

Recitation of codes

Talim was also communicated through recitation accompanied by a melodic chant or song. In traditional weaving practices, the use of chanting was common. The movement of the shuttles was synchronised with the song of the weaver, adding a musical rhythm to the instructions represented through hieroglyphics. The weaver's chant, "Two blue, one red, three yellow, two blue," served as a guide as they wove and replicated the designated pattern.

Usage

The first factories established in Amritsar around 1860 utilised Bokhara designs. However, Kashmiri weavers maintained their traditional techniques and employed the talim, instead of a cartoon, for tying knots. As a result, Amritsar became the second location in the Indian subcontinent to use the talim.

The traditional weaving practices are still carried out in some parts of the Indian subcontinent. The exact date when talim was last used in the subcontinent varies depending on the region and the specific weaving community. Indian textile historian Jasleen Dhamija wrote in her 1989 book Handwoven Fabrics of India that there were still some weavers in the Kashmiri village of Kanihama who applied talim in weaving shawls.

As of 2022, the carpet weavers in Kashmir were the only remaining users of talim in carpets, according to Zubair Ahmed, director of the Indian Institute of Carpet Technology. The institute aims to preserve traditional Kashmiri carpet designs by digitising talim and training weavers in the technique.

Gallery

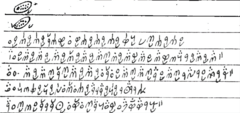

Example of a carpet talim, transcribed by British orientalist Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner (1882)

Example of a carpet talim, transcribed by British orientalist Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner (1882)

References

- ^ Kaur, Gagan Deep (2017). "Cognitive bearing of techno-advances in Kashmiri carpet designing". AI & Society. 32 (4): 509–524. doi:10.1007/s00146-016-0683-2. S2CID 253683507.

The designs in Kashmiri carpet weaving are encoded in a symbolic code, called talim, which the weavers decode while weaving the design ... The talim is a notational-cum-cryptographic system which has been devised specifically to encode the visual design in symbols.

- ^ Beardsley, Grace; Sinopoli, Carla M.; Morrison, Kathleen D. (1 January 2005). Wrapped in Beauty: The Koelz Collection of Kashmiri Shawls. University of Michigan Press. pp. 34, 42, 44, 45, 102. ISBN 978-0-915703-60-9.

Talim: Written coded plan containing instructions for shawl weaving

- ^ Dhamija, Jasleen; Jain, Jyotindra, eds. (1989). Handwoven Fabrics of India. Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing. pp. 66, 73, 128. ISBN 9780944142264. Retrieved 8 February 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Muchie, Mammo; Bhaduri, Saradindu; Baskaran, Angathevar; Sheikh, Fayaz Ahmad, eds. (2016). Informal Sector Innovations: Insights from the Global South. New York: Routledge. p. 337. ISBN 978-1-317-37200-4. Retrieved 8 February 2023 – via Google Books.

- Schmidt, Ruth Laila (1999). "15. Arabic Elements in Urdu". Urdu, an Essential Grammar. Psychology Press. p. 258. ISBN 9780415163804. Retrieved 8 February 2023 – via Google Books.

- ^ Watt, William Montgomery (1961). Islam and the Integration of Society. London: Routledge & Paul. p. 70. OCLC 255802. Retrieved 6 February 2023 – via Internet Archive.

Similarly from their emphasis on 'authoritative teaching' (ta'lim) they are known as Ta'limiyyah.

- Catafago, Joseph (1858). An English and Arabic Dictionary. London: Bernard Quaritch. p. 482. OCLC 2370934. Retrieved 8 February 2023 – via Google Books.

- Tajddin, Mumtaz Ali. "TALIM, DOCTRINE OF". F.I.E.L.D - First Ismaili Electronic Library and Database. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- Textile Trends. Calcutta: Eastland Publications. 1991. p. 44. OCLC 2624953. Retrieved 8 February 2023 – via Google Books.

- ^ Dhamija, Jasleen; Jain, Jyotindra, eds. (1989). Handwoven Fabrics of India. Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing. pp. 66, 68, 73, 74, 128. ISBN 9780944142264. Retrieved 8 February 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Anand, Mulk Raj, ed. (September 1965). "Origin of Pile Carpets and Their Development in India". Marg Pathway: A Magazine of the Arts. Vol. XVIII. Bombay: Marg Publications. pp. 6, 28 – via Internet Archive.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol (2004). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art. Hudson Hills. p. 297. ISBN 978-1-55595-238-9.

- ^ Kaur, Gagan Deep (1 May 2017). "Cognitive dimensions of talim: evaluating weaving notation through cognitive dimensions (CDs) framework". Cognitive Processing. 18 (2): 145–157. doi:10.1007/s10339-016-0788-z. ISSN 1612-4790. PMID 28032252. S2CID 254193837.

- Ames, Frank (1986). The Kashmir Shawl and Its Indo-French Influence. Antique Collectors' Club. p. 339. ISBN 978-0-907462-62-0.

- "Kashmir's famous Kani shawls get GI status". The Hindu. 22 March 2010. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ Gans-Ruedin, Erwin (1984). Indian Carpets. Translated by Howard, Valerie. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc. pp. 20, 41. ISBN 9780847805518. Retrieved 8 February 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Kaur, Gagan Deep (2020). "Linguistic mediation and code-to-weave transformation in Kashmiri carpet weaving". Journal of Material Culture. 25 (2): 220–239. doi:10.1177/1359183519862585. ISSN 1359-1835. S2CID 203053045.

- Jaitly, Jaya (2004). A Podium on the Pavement. UBSPD. p. 366. ISBN 978-81-7476-478-2.

| Weaving | ||

|---|---|---|

| Weaves |  | |

| Components | ||

| Tools and techniques | ||

| Types of looms | ||

| Weavers |

| |

| Employment practices | ||

| Mills | ||