| This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. Please consider expanding the lead to provide an accessible overview of all important aspects of the article. (December 2020) |

A crosscut hand saw about 620 mm (24 inches) long A crosscut hand saw about 620 mm (24 inches) long | |

| Classification | Cutting |

|---|---|

| Types | Hand saw Back saw Bow saw Chainsaw Circular saw Reciprocating saw Bandsaw |

| Related | Milling cutter |

A saw is a tool consisting of a tough blade, wire, or chain with a hard toothed edge used to cut through material. Various terms are used to describe toothed and abrasive saws.

Saws began as serrated materials, and when mankind learned how to use iron, it became the preferred material for saw blades of all kind. There are numerous types of hands saws and mechanical saws, and different types of blades and cuts.

Description

A saw is a tool consisting of a tough blade, wire, or chain with a hard toothed edge. It is used to cut through material, very often wood, though sometimes metal or stone.

Terminology

A number of terms are used to describe saws.

Kerf

"Kerf" redirects here. For other meanings, see Kerf (disambiguation).

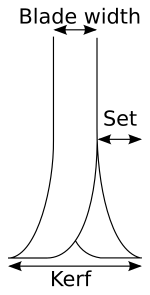

The narrow channel left behind by the saw and (relatedly) the measure of its width is known as the kerf. As such, it also refers to the wasted material that is turned into sawdust, and becomes a factor in measurements when making cuts. For example, cutting an 8 foot (2.4 meter) piece of wood into 1 foot (30 cm) sections, with 1/8 inch (3 mm) kerf will produce only seven sections, plus one that is 7/8 inch (21 mm) too short when factoring in the kerf from all the cuts. The kerf depends on several factors: the width of the saw blade; the set of the blade's teeth; the amount of wobble created during cutting; and the amount of material pulled out of the sides of the cut. Although the term "kerf" is often used informally, to refer simply to the thickness of the saw blade, or to the width of the set, this can be misleading, because blades with the same thickness and set may create different kerfs. For example, a too-thin blade can cause excessive wobble, creating a wider-than-expected kerf. The kerf created by a given blade can be changed by adjusting the set of its teeth with a tool called a saw tooth setter. The kerf left behind by a laser beam can be changed based on the laser's power and type of material being cut.

Toothed saws

A toothed saw or tooth saw has a hard toothed edge. The cut is made by placing the toothed edge against the material and moving it back and forth, or continuously forward. This force may be applied by hand, or powered by steam, water, electricity or other power source.

Frequency of teeth

The most common measurement of the frequency of teeth on a saw blade is point per inch (25 mm). It is taken by setting the tip (or point) of one tooth at the zero point on a ruler, and then counting the number of points between the zero mark and the one-inch mark, inclusive (that is, including both the point at the zero mark and any point that lines up precisely with the one-inch mark). There is always one more point per inch than there are teeth per inch (e.g., a saw with 14 points per inch will have 13 teeth per inch, and a saw with 10 points per inch will have 9 teeth per inch). Some saws do not have the same number of teeth per inch throughout their entire length, but the vast majority do. Those with more teeth per inch at the toe are described as having incremental teeth, in order to make starting the saw cut easier.

An alternative measurement of the frequency of teeth on a saw blade is teeth per inch. Usually abbreviated TPI, as in, "a blade consisting of 18TPI." (cf. points per inch.)

Set

Set is the degree to which the teeth are bent out sideways away from the blade, usually in both directions. In most modern serrated saws, the teeth are set, so that the kerf (the width of the cut) will be wider than the blade itself. This allows the blade to move through the cut easily without binding (getting stuck). The set may be different depending on the kind of cut the saw is intended to make. For example, a ripsaw has a tooth set that is similar to the angle used on a chisel, so that it rips or tears the material apart. A "flush-cutting saw" has no set on one side, so that the saw can be laid flat on a surface and cut along that surface without scratching it. The set of the blade's teeth can be adjusted with a tool called a saw set.

Other toothed saw terms

- Back: The edge opposite the toothed edge.

- Fleam: The angle of the faces of the teeth relative to a line perpendicular to the face of the saw.

- Gullet: The valley between the points of the teeth.

- Heel: The end closest to the handle.

- Rake: The angle of the front face of the tooth relative to a line perpendicular to the length of the saw. Teeth designed to cut with the grain (ripping) are generally steeper than teeth designed to cut across the grain (crosscutting)

- Teeth: Sharp protrusions along the cutting side of the saw.

- Toe: The end farthest from the handle.

- Toothed edge: the edge with the teeth (on some saws both edges are toothed).

- Web: a narrow saw blade held in a frame, worked either by hand or in a machine, sometimes with teeth on both edges

Abrasive saws

Main article: Abrasive sawAn abrasive saw has a powered circular blade designed to cut through metal or ceramic.

History

Saws were at first serrated materials such as flint, obsidian, sea shells and shark teeth.

Serrated tools with indications that they were used to cut wood were found at Pech-de-l'Azé caveIV in France. These tools date to 90,000-30,000 years BCE.

In ancient Egypt, open (unframed) pull saws made of copper are documented as early as the Early Dynastic Period, c. 3,100–2,686 BC. Many copper saws were found in tomb No. 3471 dating to the reign of Djer in the 31st century BC. Saws were used for cutting a variety of materials, including humans (death by sawing), and models of saws were used in many contexts throughout Egyptian history. Particularly useful are tomb wall illustrations of carpenters at work that show the sizes and use of different types of saws. Egyptian saws were at first serrated, hardened copper which may have cut on both pull and push strokes. As the saw developed, teeth were raked to cut only on the pull stroke and set with the teeth projecting only on one side, rather than in the modern fashion with an alternating set. Saws were also made of bronze and later iron. In the Iron Age, frame saws were developed holding the thin blades in tension. The earliest known sawmill is the Roman Hierapolis sawmill from the third century AD and was for sawing stone.

According to Chinese legend, the saw was invented by Lu Ban. In Greek mythology, as recounted by Ovid, Talos, the nephew of Daedalus, invented the saw. In archeological reality, saws date back to prehistory and most probably evolved from Neolithic stone or bone tools. "he identities of the axe, adz, chisel, and saw were clearly established more than 4,000 years ago."

Manufacture of saws by hand

Once mankind had learned how to use iron, it became the preferred material for saw blades of all kinds; some cultures learned how to harden the surface ("case hardening" or "steeling"), prolonging the blade's life and sharpness.

Steel, made of iron with moderate carbon content and hardened by quenching hot steel in water, was used as early as 1200 BC. By the end of the 17th century European manufacture centred on Germany, (the Bergisches Land) in London, and the Midlands of England. Most blades were made of steel (iron carbonised and re-forged by different methods). In the mid 18th century a superior form of completely melted steel ("crucible cast") began to be made in Sheffield, England, and this rapidly became the preferred material, due to its hardness, ductility, springiness and ability to take a fine polish. A small saw industry survived in London and Birmingham, but by the 1820s the industry was growing rapidly and increasingly concentrated in Sheffield, which remained the largest centre of production, with over 50% of the nation's saw makers. The US industry began to overtake it in the last decades of the century, due to superior mechanisation, better marketing, a large domestic market, and the imposition of high tariffs on imports. Highly productive industries continued in Germany and France.

Early European saws were made from a heated sheet of iron or steel, produced by flattening by several men simultaneously hammering on an anvil. After cooling, the teeth were punched out one at a time with a die, the size varying with the size of the saw. The teeth were sharpened with a triangular file of appropriate size, and set with a hammer or a wrest. By the mid 18th century rolling the metal was usual, the power for the rolls being supplied first by water, and increasingly by the early 19th century by steam engines. The industry gradually mechanized all the processes, including the important grinding the saw plate "thin to the back" by a fraction of an inch, which helped the saw to pass through the kerf without binding. The use of steel added the need to harden and temper the saw plate, to grind it flat, to smith it by hand hammering and ensure the springiness and resistance to bending deformity, and finally to polish it.

Most hand saws are today entirely made without human intervention, with the steel plate supplied ready rolled to thickness and tensioned before being cut to shape by laser. The teeth are shaped and sharpened by grinding and are flame hardened to obviate (and actually prevent) sharpening once they have become blunt. A large measure of hand finishing remains to this day for quality saws by the very few specialist makers reproducing the 19th century designs.

Pit saws

Main articles: Whipsaw, Saw pit, and Two-man sawA pit saw was a two-man ripsaw. In parts of early colonial North America, it was one of the principal tools used in shipyards and other industries where water-powered sawmills were not available. It was so-named because it was typically operated over a saw pit, either at ground level or on trestles across which logs that were to be cut into boards. The pit saw was "a strong steel cutting-plate, of great breadth, with large teeth, highly polished and thoroughly wrought, some eight or ten feet in length" with either a handle on each end or a frame saw. A pit-saw was also sometimes known as a whipsaw. It took 2-4 people to operate. A "pit-man" stood in the pit, a "top-man" stood outside the pit, and they worked together to make cuts, guide the saw, and raise it. Pit-saw workers were among the most highly paid laborers in early colonial North America.

Types of saws

Hand saws

Main article: Hand saw

Hand saws typically have a relatively thick blade to make them stiff enough to cut through material. (The pull stroke also reduces the amount of stiffness required.) Thin-bladed handsaws are made stiff enough either by holding them in tension in a frame, or by backing them with a folded strip of steel (formerly iron) or brass (on account of which the latter are called "back saws.") Some examples of hand saws are:

- Artillery saw, Chain saw, Portable link saw: a flexible chain saw up to 122 cm (four feet) long, supplied to the military for clearing tree branches for gun sighting;

- Butcher's saw: for cutting bone; many different designs were common, including a large one for two men, known in the USA as a beef-splitter; most were frame saws, some backsaws;

- Crosscut saw: for cutting wood perpendicular to the grain;

- Docking saw: a large, heavy saw with an unbreakable metal handle of unique pattern, used for rough work

- Farmer's/Miner's saw: a strong saw with coarse teeth;

- Felloe saw;: the narrowest-bladed variety of pit saw, up to 213 cm (7 feet) long and able to work the sharp curves of cart wheel felloes; a slightly wider blade, equally long, was called a stave saw, for cutting the staves for wooden casks;

- Floorboard/flooring saw: a small saw, rarely with a back, and usually with the teeth continued onto the back at the toe for a short distance; used by house carpenters for cutting across a floor board without damaging its neighbour;

- Grafting/grafter/table saw; a hand saw with a tapering narrow blade from 15 to 76 cm (6 to 30 inches) long; the origins of the terms are obscure

- Ice saw: either of pit saw design without a bottom tiller, or a large handsaw, always with very coarse teeth, for harvesting ice to be used away from source, or stored for use in warmer weather;

- Japanese saw or pull saw: a thin-bladed saw that cuts on the pull stroke, and with teeth of different design to European or American traditional forms;

- Keyhole saw or compass saw: a narrow-bladed saw, sharply tapered thin to the back to cut round curves, with one end fixed in a handle;

- Musical saw, a hand saw, possibly with the teeth filed off, used as a musical instrument.

- Nest of saws: three or four interchangeable blades fitted to a handle with screws or quick-release nuts;

- One-man cross cut saw: a coarse-toothed saw of 76 to 152 cm (30-60 inches) length for rough or green timber; a second, turned, handle could be added at the heel or the toe for a second operator;

- Pad saw: a short narrow blade held in a wooden or metal handle (the pad);

- Panel saw: a lighter variety of handsaw, usually less than 61 cm (24 inches) long and having finer teeth;

- Plywood saw: a fine-toothed saw (to reduce tearing), for cutting plywood

- Polesaw: a saw blade attached to a long handle

- Pruning saw: the commonest variety has a 30-71 cm (12-28 inch) blade, toothed on both edges, one tooth pattern being considerably coarser than the other;

- Ripsaw: for cutting wood along the grain;

- Rule saw or combination saw: a handsaw with a measuring scale along the back and a handle making a 90° square with the scaled edge;

- Salt saw: a short hand saw with a non-corroding zinc or copper blade, used for cutting a block of salt at a time when it was supplied to large kitchens in that form;

- Turkish saw or monkey saw: a small saw with a parallel-sided blade, designed to cut on the pull stroke;

- Two-man saw: a general term for a large crosscut saw or ripsaw for cutting large logs or trees;

- Veneer saw: a two-edged saw with fine teeth for cutting veneer;

- Wire saw: a toothed or coarse cable or wire wrapped around the material and pulled back and forth.

Back saws

Further information: Backsaw and Japanese saw"Back saws" which have a thin blade backed with steel or brass to maintain rigidity, are a subset of hand saws. Back saws have different names depending on the length of the blade; "tenon saw" (from use in making mortise and tenon joints) is often used as a generic name for all the sizes of woodworking backsaw. Some examples are:

- Bead saw/gent's saw/jeweller's saw: a small backsaw with a turned wooden handle;

- Blitz saw: a small backsaw, for cutting wood or metal, with a hook at the toe for the thumb of the non-dominant hand;

- Carcase saw: a term used until the 20th century for backsaws with 10–14 in (25–36 cm) long blades;

- Dovetail saw: a backsaw with a blade of 6–10 in (15–25 cm) length, for cutting intricate joints in cabinet making work;

- Electrician's saw: a very small backsaw used in the early 20th century on the wooden capping and casing in which electric wiring was run;

- Flush-cutting saw/offset saw: a backsaw with a flat side and a handle offset toward the opposite side, usually reversible, for cutting flush to a surface such as a floor;

- Mitre-box saw: a saw with a blade 18–34 in (46–86 cm) long, held in an adjustable frame (the mitre box) for making accurate crosscuts and mitres in a workplace;

- Sash saw: a backsaw of blade length 14–16 in (36–41 cm).

Frame saws

A class of saws for cutting all types of material; they may be small or large and the frame may be wood or metal.

- Bow saw, turning saw, or buck saw: a saw with a narrow blade held in tension in a frame; the blade can usually be rotated and may be toothed on both edges; it may be a rip or a crosscut, and was the preferred form of hand saw for continental European woodworkers until superseded by machines;

- Coping saw: a saw with a very narrow blade held in a metal frame in which it can usually be rotated, for cutting wood patterns;

- Felloe saw; a pit saw with a narrow tapering blade for sawing out the felloes of wooden cart wheels

- Fretsaw: a saw with a very narrow blade which can be rotated, held in a deep metal frame, for cutting intricate wood patterns such as jigsaw puzzles;

- Girder saw: a large hack saw with a deep frame;

- Hacksaw/bow saw for iron: a fine-toothed blade held in a frame, for cutting metal and other hard materials;

- Pit saw/sash saw/whip saw: large wooden-framed saws for converting timber to lumber, with blades of various widths and lengths up to 305 cm (10 feet); the timber is supported over a pit or raised on trestles; other designs are open-bladed;

- Stave saw: a narrow tapering-bladed pit saw for sawing out staves for wooden casks;

- Surgeon's/surgical saw/Bone cutter: for cutting bone during surgical procedures; some designs are framed, others have an open blade with a characteristic shape of the toe.

Mechanically powered saws

Circular-blade saws

- Circular saw: a saw with a circular blade which spins. Circular saws can be large for use in a mill or hand held up to 24" blades and different designs cut almost any kind of material including wood, stone, brick, plastic, etc.

- Table saw: a saw with a circular blade rising through a slot in a table. If it has a direct-drive blade small enough to set on a workbench, it is called a "workbench" or "jobsite" saw. If set on steel legs, it is called a "contractor's saw." A heavier, more precise and powerful version, driven by several belts, with an enclosed base stand, is called a "cabinet saw." A newer version, combining the lighter-weight mechanism of a contractor's saw with the enclosed base stand of a cabinet saw, is called a "hybrid saw."

- Radial arm saw: a versatile machine, mainly for cross-cutting. The blade is pulled on a guide arm through a piece of wood that is held stationary on the saw's table.

- Rotary saw or "spiral-cut saw" or "RotoZip": for making accurate cuts, without using a pilot hole, in wallboard, plywood, and other thin materials.

- Electric miter saw or "chop saw," or "cut-off saw" or "power miter box": for making accurate cross cuts and miter cuts. The basic version has a circular blade fixed at a 90° angle to the vertical. A "compound miter saw" has a blade that can be adjusted to other angles. A "sliding compound miter saw" has a blade that can be pulled through the work, in an action similar to that of a radial-arm saw, which provides more capacity for cutting wider workpieces.

- Concrete saw: (usually powered by an internal combustion engine and fitted with a Diamond Blade) for cutting concrete or asphalt pavement.

- Pendulum saw or "swing saw": a saw hung on a swinging arm, for the rough cross cutting of wood in a sawmill and for cutting ice out of a frozen river.

- Abrasive saw: a circular or reciprocating saw-like tool with an abrasive disc rather than a toothed blade, commonly used for cutting very hard materials. As it does not have regularly shaped edges the abrasive saw is not a saw in technical terms.

- Hole saw: ring-shaped saw to attach to a power drill, used for cutting a circular hole in material.

Reciprocating blade saws

- Dragsaw: for bucking logs (used before the invention of the chainsaw).

- Frame saw or sash saw: A thin bladed rip-saw held in tension by a frame used both manually and in sawmills. Some whipsaws are frame saws and some have a heavy blade which does not need a frame called a mulay or muley saw.

- Ice saw: for ice cutting. Looks like a mulay saw but sharpened as a cross-cut saw.

- Jigsaw or "saber saw" (US): narrow-bladed saw, for cutting irregular shapes. (Also an old term for what is now more commonly called a "scroll saw.")

- Power hacksaw or electric hacksaw: a saw for cutting metal, with a frame like a normal hacksaw.

- Reciprocating saw or "sabre saw" (UK and Australia): a saw with an "in-and-out" or "up-and-down" action similar to a jigsaw, but larger and more powerful, and using a longer stroke with the blade parallel to the barrel. Hand-held versions, sometimes powered by compressed air, are for demolition work or for cutting pipe.

- Scroll saw: for making intricate curved cuts ("scrolls").

- Sternal saw: for cutting through a patient's sternum during surgery.

Continuous band

- Band saw: a ripsaw on a motor-driven continuous band. Portable sawmills are typically band saw mills.

Chainsaws

- Chainsaw: an engine-driven saw with teeth on a chain normally used as a cross-cut saw.

- Chainsaw mill: a chainsaw with a special saw chain and guide system for use as a rip-saw.

Types of blades and blade cuts

Most blade teeth are made either of tool steel or carbide. Carbide is harder and holds a sharp edge much longer.

- Band saw blade

- A long band welded into a circle, with teeth on one side. Compared to a circular-saw blade, it produces less waste because it is thinner, dissipates heat better because it is longer (so there is more blade to do the cutting, and is usually run at a slower speed.

- Crosscut

- In woodworking, a cut made at (or close to) a right angle to the direction of the wood grain of the workpiece. A crosscut saw is used to make this type of cut.

- Rip cut

- In woodworking, a cut made parallel to the direction of the grain of the workpiece. A ripsaw is used to make this type of cut.

- Plytooth blade

- A circular saw blade with many small teeth, designed for cutting plywood with minimal splintering.

- Dado blade

- A special type of circular saw blade used for making wide-grooved cuts in wood so that the edge of another piece of wood will fit into the groove to make a joint. Some dado blades can be adjusted to make different-width grooves. A "stacked" dado blade, consisting of chipper blades between two dado blades, can make different-width grooves by adding or removing chipper blades. An "adjustable" dado blade has a movable locking cam mechanism to adjust the degree to which the blade wobbles sideways, allowing continuously variable groove widths from the lower to upper design limits of the dado.

- Strobe saw blade

- A circular saw blade with special rakers/cutters to easily saw through green or uncured wood that tends to jam other kinds of saw blades.

Materials used for saws

There are several materials used in saws, with each of its own specifications.

- Brass

- Used only for the reinforcing folded strip along the back of backsaws, and to make the screws that in earlier times held the blade to the handle.

- Iron

- Used for blades and for the reinforcing strip on cheaper backsaws until superseded by steel.

- Zinc

- Used only for saws made to cut blocks of salt, as formerly used in kitchens

- Copper

- Used as an alternative to zinc for salt-cutting saws

- Steel

- Used in almost every existing kind of saw. Because steel is cheap, easy to shape, and very strong, it has the right properties for most kind of saws.

- Diamond

- Fixed onto the saw blade's base to form diamond saw blades. As diamond is a superhard material, diamond saw blades can be used to cut hard brittle or abrasive materials, for example, stone, concrete, asphalt, bricks, ceramics, glass, semiconductor and gem stone. There are many methods used to fix the diamonds onto the blades' base and there are various kinds of diamond saw blades for different purposes.

- High-speed steel (HSS)

- The whole saw blade is made of High-Speed Steel (HSS). HSS saw blades are mainly used to cut steel, copper, aluminum and other metal materials. If high-strength steels (e.g., stainless steel) are to be cut, the blades made of cobalt HSS (e.g. M35, M42) should be used.

- Tungsten carbide

- Normally, there are two ways to use tungsten carbide to make saw blades:

- Carbide-tipped saw blades

- The saw blade's teeth are tipped (via welding) with small pieces of sharp tungsten carbide block. This type of blade is also called TCT (Tungsten Carbide-Tipped) saw blade. Carbide-tipped saw blades are widely used to cut wood, plywood, laminated board, plastic, glass, aluminum and some other metals.

- Solid-carbide saw blades

- The whole saw blade is made of tungsten carbide. Comparing with HSS saw blades, solid-carbide saw blades have higher hardness under high temperatures, and are more durable, but they also have a lower toughness.

Uses

- Saws are commonly used for cutting hard materials. They are used extensively in forestry, construction, demolition, medicine, and hunting.

- Musical saws are used as instruments to make music.

- Chainsaw carving is a flourishing modern art form. Special saws have been developed for the purpose.

- The production of lumber, lengths of squared wood for use in construction, begins with the felling of trees and the transportation of the logs to a sawmill.

- Plainsawing: Lumber that will be used in structures is typically plainsawn (also called flatsawn), a method of dividing the log that produces the maximum yield of useful pieces and therefore the greatest economy.

- Quarter sawing: This sawing method produces edge-grain or vertical grain lumber, in which annual growth rings run more consistently perpendicular to the pieces' wider faces.

See also

- Carbide saw

- Diamond tools

- Fire-saw

- Japanese saw

- Saw chain

- Saw pit

- Sawmill

- Sawgrass (disambiguation)

- Sharpening

- Two-man saw

- Watersaw

References

- Barley, Simon "British Saws and Saw Makers from c1660, 2014

- ^ "P. d'A. Jones and E. N. Simons, "Story of the Saw" Spear and Jackson Limited 1760-1960" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 26, 2013.

- The middle paleolithic site of Pech de l'Azé IV. Harold L. Dibble, Shannon J. P. McPherron, Paul Goldberg, Dennis M. Sandgathe. Cham, Switzerland. 2018. ISBN 978-3-319-57524-7. OCLC 1007823303.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - Harris, J.; Lucas., A. (2012). Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries. Dover. p. 449. ISBN 9780486144948.

- "The 1st Dynasty Tombs of Saqqara in Egypt". Archived from the original on 2016-02-25. Retrieved 2016-01-15. The 1st Dynasty Tombs of Saqqara in Egypt by John Watson

- Lu Ban and The Invention of the Saw Archived 2011-02-04 at the Wayback Machine History Anecdote at Cultural China website

- Ovid Metamorphoses Bk VIII:236-259: The death of Talos Archived 2011-02-17 at the Wayback Machine A. S. Kline translation, Electronic Text Center at University of Virginia Library

- Richard S. Hartenberg, Joseph A. McGeough Neolithic Hand Tools Archived 2008-09-06 at the Wayback Machine at Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- Jones & Simons, Story of the Saw, p15

- ^ Moxon, J: Mechanick Exercises, p95-99

- Barley, Simon, British Saws and Saw Makers from c1660, p7

- Barley, Simon, British Saws and Saw Makers from c1660, p42

- Tweedale, G., Sheffield Steel and America, ch 11

- Barley, Simon, British Saws and Saw Makers from c1660, p 11.

- Moxon, J: Mechanick Exercises, p 95.

- Barley, Simon, British Saws and Saw Makers from c1660, pp. 5-22.

- Charles W. Upham Salem Witchcraft with an account of Salem Village and a History of Opinions on Witchcraft and Kindred Subjects. Frederick Unger, New York, 1978 (Reprint), 2 vols., vol. 1, p 191

- Glossary of Tools Archived 2009-09-26 at the Wayback Machine at (American) Pilgrim Hall Museum website

- Massingham, H. J., and Thomas Hennell. Country relics; an account of some old tools and properties once belonging to English craftsmen and husbandmen saved from destruction and now described with their users and their stories. Cambridge, Eng.: University Press, 1939.reprint 2011 ISBN 9781107600706 books.google.com/books?id=6_auYCccqoQC&pg

- Salaman, Dictionary, p420 and 433

- "Cole Land Transportation Museum - Cole Museum". www.colemuseum.org.

Salaman, R A, Dictionary of Woodworking Tools, revised edition 1989

Further reading

- Naylor, Andrew. A review of wood machining literature with a special focus on sawing. BioRes, April 2013

- The Saw in History. Philadelphia: Henry Disston & Sons. 1915. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

External links

| Forestry tools and equipment | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tree planting, afforestation |

|  |

| Mensuration | ||

| Fire suppression | ||

| Axes |

| |

| Saws | ||

| Logging | ||

| Other | ||

| ||

| Woodworking | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overviews | |||||||||

| Occupations |

| ||||||||

| Woods |

| ||||||||

| Tools |

| ||||||||

| Geometry |

| ||||||||

| Treatments | |||||||||

| Organizations |

| ||||||||

| Conversion | |||||||||

| Techniques | |||||||||