Tiraz (Arabic: طراز, romanized: ṭirāz; Persian: تراز, romanized: tarāz or terāz) The Persian word for a type of embroidery and clothing textiles, are medieval Islamic embroideries, usually in the form of armbands sewn onto robes of honour (khilat). They were bestowed upon high-ranking officials who showed loyalty to the Caliphate, and given as gifts to distinguished individuals. They were usually inscribed with the ruler's names, and were embroidered with threads of precious metal and decorated with complex patterns. Tiraz were a symbol of power; their production and export were strictly regulated, and were overseen by a government-appointed official.

They were likely influenced by the tablion, a decorated patch added to the body of the mantle as a badge of rank or position in late Roman and Byzantine dress.

Etymology

The ultimate origin of this word is Persian darz (دَرْز), which means "embroidery". The word tiraz can be used to refer to the textiles themselves, but is mostly used as a term for medieval textiles with Arabic inscription, or to the band of calligraphic inscription on them, or to the factories which produced the textiles (known as the dar al-tiraz).

Tiraz is also known as taraziden in Persian.

Culture and influence

While the term tiraz is applicable to any luxury textile predating 1500 CE, it is primarily attributed to luxury textiles from the Islamic world with an Arabic inscription. Before the Umayyad caliphate, these textiles would originally bear Greek writing, but with the succession of Caliph 'Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan came the implementation of Arabic script on the textiles.

The earliest datable textile with a tiraz band can be traced back to the Umayyad caliphate, ascribed to the ruler Marwan I or Marwan II, though there is general consensus the tiraz was intended for the latter caliph. However, the institution of tiraz flourished in the Islamic world under the patronage of the Abbasid and Fatimid caliphs from the late 9th century to the 13th.

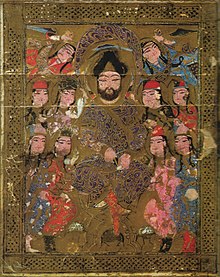

Armbands were not the sole item that the caliphs chose to mark with their name. Garments such as turbans and sleeves, robes of honor, cushions, curtains, camel covers, and even court musician's horns would be embellished with the caliph's tiraz. Turbans, or taj, are also synonymous with the word 'crown'. Muslim rulers preferred to put their names and texts praising God on the tiraz rather than figures. During this time, the bands of script found on mosques were also referred to as tiraz, making the term applicable across a wide range of mediums.

As the Umayyad caliphate prospered in Spain, the influence of the tiraz spread to the neighboring European countries and into their art and symbolism. The Mantel of Roger II serves as a prime example as it holds an embroidered inscription along the rim of the bottom of the regalia. The kufic script uses flowery diction, quoting tiraz tradition, and bestows blessings upon the ruler. Since Arabic was not the primary language of the Norman king, nor Sicily, and the decoration of the mantel used traditional motifs reserved for caliphs, the regalia was a clear influence of the conquered power that was the Umayyad caliphate. Despite being implemented in a European environment, the article of clothing is thought to be made by Muslim artisans in a workshop located in Palermo, Sicily. The Islamic textile aesthetic can also be traced in Giotto's piece, "Madonna and Child", as the pattern around the Madonna's head imitates kufic script and ultimately draws upon the influence of the tiraz as a symbol of power.

History of Islamic dress code

The notion of dress code in the Islamic world evolved early at the beginning of the expansion of the new empire. As the empire expanded, cultural divisions were established, each with its own dress code. The Arabs, a minority in their own empire, distinguished themselves by establishing a rule which would initiate differentiation (ghiyar) to maintain identity. Regulation of this kind was first ascribed to caliph Umar (r. 634–644) in the so-called Pact of Umar, a list of rights and restrictions on protected non-Muslims (dhimmi) which would grant security of their persons, families, and possessions. As the vestimentary system evolved, so to the application of the rule. Requirements were also applied to the Arab military; for example, Arab warriors set up in the eastern provinces were forbidden to wear the Persian khaftan (cuirass) and ran (leggings).

By the end of the Umayyad Caliphate in the mid 8th-century, dress code law had become less strict. Arabs living in remote provinces such as Khurasan had become assimilated with the local culture, including the way they dressed. The trend of moving away from the stricter vestimentary system also occurred in the high-ranking officials, even at early times. It has been recorded that Arab rulers of the Umayyad dynasty already wore Persian-style coats, with pantaloons and qalansuwa turbans. High-ranking Umayyad officials also adopted the custom of wearing luxurious garments of silk, satin, and brocade, in imitation of the Byzantine and Sasanian courts. Tiraz garments indicate to whom the wearer was loyal, by means of an inscription (e.g. the name of the ruling caliph), similar with the minting of the caliph's name on coins (sikka).

Tiraz bands were presented to loyal subjects in a formal ceremony, known as the khil'a ("robe of honor") ceremony, which can be traced as far as the time of Muhammad. The term "khil'a" literally means "cast-off", and originally a khil'a was a piece of clothing actually worn by the ruler and given to another. By the tenth century, the caliphal textile mills produced these robes specifically for honorific purpose. High-quality gold tiraz bands, embroidered onto silk robes, were bestowed to deserving viziers and other high-ranking officials; the quality of tiraz reflected the influence (and wealth) of the recipient.

The Umayyads were later succeeded by the Abbasids in 750 CE, but the tiraz still held its previous symbolic role of power and propaganda. The tiraz had such a strong influence within the political context of the Abbasid caliphate that it was used, at times, as a means of usurpation. This could be seen with the appointment of al‐Muwaffaq, a highly influential force within the caliphate, as the viceroy of the East in 875 CE by his brother, caliph al‐Muʿtamid. The succession proved as a threat for Ahmad ibn Tulun, the Turkic governor of Egypt, as al‐Muwaffaq had extinguished his efforts to destabilize his, al‐Muwaffaq's control. In Ibn Tulun's reprisal, he ceased the mention of al‐Muwaffaq on tiraz inscriptions, which emphasized the importance of the tiraz in the political context and its influence on one's courtly status in the public's eye.

With the spread of Islam came rising caliphates, triggering a paradigm shift in the role of the tiraz. The grip of the Abbasid caliphate was weakened as they lost control over their Turkic slave armies and Egypt's Fatimids and Spain's Umayyads began to establish their rule. In Fatimid court, guilloche decorations began to be used and a new concept of juxtaposing figures with text was introduced due to Roman influence. Through their establishment, the Fatimids brought with them a new use of the tiraz: bestowing robes of honor in non-court context. As the custom of bestowing robes of honor spread, public studios (‘amma) began imitating the custom of bestowing tiraz by producing their own tiraz for public use. In Fatimid Egypt, people who could afford the ‘amma tiraz would perform their own "khil'a" ceremony on family and friends, as documented in the documents of Cairo Geniza and relics found in Cairo. These "public tiraz" were considered family treasures and passed down as heirlooms. Tiraz were also given as gifts. A sovereign in Andalusia was recorded to present a tiraz to another sovereign in North Africa.

Tiraz was also used in funerary rituals. In Fatimid Egyptian funeral tradition, a tiraz band was wrapped around the head of the deceased with their eyes covered with it. The blessings imbued into the tiraz from the earlier khil'a ceremony, as well as the fact that there was the inscription of Quranic verses, would make the tiraz especially suited for funeral ceremonies.

By the 13th century, tiraz production started to decline. With the weakening of the Islamic power, nobles began to sold their tiraz on the open market. Some tiraz served as a form of investment where they were traded and sold. Despite the decline, tiraz continued to be produced up into the 14th-century.

Design and production

There were two types of tiraz factories: the official caliphal (khassa, meaning "private" or "exclusive") and the public (‘amma, meaning "public"). There are no differences in design between the tiraz produced in the caliphal and public factories, because both were designed with the same name of the ruling caliph, and both had the same quality. The ‘amma factories produced tiraz for commercial use. The more official khassa factories were more like administrative departments, controlling and enrolling craftsmen who worked in production factories located away from the center, normally in places known for the production of a particular fabric.

Tiraz garments vary in their material and design, depending on the time of their production, where they are produced and for whom they are produced. Fabrics e.g. linen, wool, cotton or mulham (mixture of silk warp and cotton weft) were used for tiraz production. The Yemeni tiraz has the characteristic striped lozenge design of green, yellow, and brown; this is produced through resist-dyeing and ikat technique. In Egypt, tiraz were left undyed but embroidered with red or black thread. Most early tiraz was decorated with colorful motifs of medallions or animals, but with no inscription. Discovery of tiraz across the periods shows a gradual transition from Sasanian, Coptic and Byzantine style. During the Fatimid period in 11th- and 12th-century Egypt, the trend of tiraz design shows a revival of these styles.

Inscriptions were usually found in tiraz from the later periods. The inscriptions can be made of gold thread or painted. The inscriptions were written in Arabic. The Kufic script (and its variation, the floriated Kufic) were found in earlier tiraz. In later period, the naskh or thuluth script became common. The inscriptions were designed in calligraphy to form artistic rhythmic pattern. The inscription may contain the name of the ruling caliph, the date and the place of manufacture, phrases taken from the Quran or from many invocations to Allah. The khassikiya (royal bodyguard) of the Mamluk sultans of Egypt wore a highly decorative tiraz woven with gold or silver metallic thread. In Fatimid Egypt, silk tiraz woven with golden inscription were reserved for the vizier and other high-ranking officials, while general public wore linen.

See also

References

Citations

- Flood, Finbarr Barry (2017). A Turk in the Dukhang? Comparative Perspectives on Elite Dress in Medieval Ladakh and the Caucasus. Austrian Academy of Science Press. p. 231 & 247.

- Wulff, Hans E. (1966). The Traditional Crafts of Persia; their Development, Technology, and Influence on Eastern and Western Civilizations. Internet Archive. Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press. pp. 216–218.

- ^ Ekhtiar & Cohen 2015.

- ^ Mackie, Louise W. (2016-09-01). "Symbols of Power: Luxury Textiles from Islamic Lands, 7th–21st Century". West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture. 23 (2): 85. doi:10.1086/691619. ISSN 2153-5531.

- "Brooklyn Museum". www.brooklynmuseum.org. Retrieved 2019-11-03.

- Jonathan Bloom, Sheila Blair (2009). Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture: Three-Volume Set. Vol III. Oxford University Press. p. 337.

- ^ Meri 2005, p. 160.

- Beckwith 2009, p. 132.

- ^ Fossier 1986, p. 263.

- ^ Meri 2005, p. 180.

- ^ "Tiraz Textile Fragment". Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2017. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- Meri 2005, pp. 180–1.

Sources

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400829941.

- Ekhtiar, Maryam; Cohen, Julia (2015). "Tiraz: Inscribed Textiles from the Early Islamic Period". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- Fossier, Robert (1986). The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521266444.

- Meri, Josef W. (2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 9781135455965.

- Stillman, Yedida Kalfon (2003). Norman A. Stillman (ed.). Arab Dress, A Short History: From the Dawn of Islam to Modern Times (Revised Second ed.). Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11373-2.

External links

Media related to Tiraz at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tiraz at Wikimedia Commons