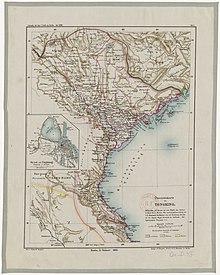

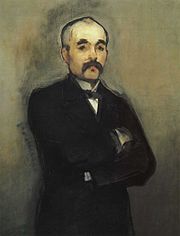

The Tonkin Affair, (French: L'Affaire du Tonkin) named after the French protectorate of Tonkin, of March 1885 was a major French political crisis that erupted in the closing weeks of the Sino-French War. It effectively destroyed the political career of the French prime minister, Jules Ferry, and abruptly ended the string of Republican governments inaugurated several years earlier by Léon Gambetta. The suspicion by the French public and political classes that French troops were being sent to their deaths far from home for little measurable gain, both in Tonkin and elsewhere, also discredited French colonial expansion for nearly a decade.

The "Lạng Sơn telegram"

The "Affair" (as most French political scandals are still termed), was triggered on 28 March 1885 by the controversial Retreat from Lạng Sơn. The retreat, which threw away the gains of the February Lạng Sơn Campaign, was ordered by Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Gustave Herbinger, the acting commander of the 2nd Brigade, less than a week after General François de Négrier's defeat at the Battle of Bang Bo (24 March 1885). General Louis Brière de l'Isle, the commander-in-chief of French forces in Tonkin, was in Hanoi at the time, and was planning to shift his headquarters to Hưng Hóa, to supervise a planned offensive against the Yunnan Army around Tuyên Quang. Brière de l'Isle concluded that the Red River Delta was in jeopardy and fired off a telegram on the evening of 28 March to the French government, warning that the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps faced disaster unless it was immediately reinforced:

I am grieved to tell you that General de Négrier is seriously wounded and Lạng Sơn has been evacuated.

The Chinese forces advanced in three large groups, and fiercely assaulted our positions in front of Ky Lua. Facing greatly superior numbers, short of ammunition, and exhausted from a series of earlier actions, Colonel Herbinger has informed me that the position was untenable and that he has been forced to fall back tonight on Dong Song and Thanh Moy. All my efforts are being applied to concentrate our forces at the passes around Chu and Kép. The enemy continues to grow stronger on the Red River, and it appears that we are facing an entire Chinese army, trained in the European style and ready to pursue a concerted plan. I hope in any event to be able to hold the entire Delta against this invasion, but I consider that the government must send me reinforcements (men, ammunition, and pack animals) as quickly as possible.

The news contained in the 'Lạng Sơn telegram', as it was immediately dubbed, ignited a political crisis in Paris:

There was enormous feeling throughout France. This retreat of 2,500 men, who had returned to their starting positions without even being pursued by the enemy, took on from a distance the proportions of an irretrievable disaster. On the stock exchange on 30 March the 3% fell by three and a half francs; it had only fallen by two and a half francs on the day that war was declared in 1870. All the newspapers were full of accusations against the Cabinet, of false accounts of the 'bitter combats' that the 2nd Brigade, enveloped by the Chinese, must have fought to disengage, of fears for the entire expeditionary corps, whose situation was depicted as tragic. In the House, the deputies who were systematically opposed to our establishment in Tonkin were jubilant, and the proponents of a colonial policy did not dare defend their views of the previous day.

The fall of Ferry's ministry, 30 March 1885

Brière de l'Isle's cable of 28 March gave the impression that a catastrophe had befallen the Tonkin expeditionary corps, and none of his later reassurances was able to entirely efface this initial impression. Although it knew by the evening of 29 March that Herbinger had halted his retreat at Dong Song and that Brière de l'Isle was stabilising the situation, the army ministry remained stunned by the news that Lạng Sơn had been abandoned, and decided to disclose the contents of both cables to the National Assembly on 30 March. Ferry attempted to use the occasion to demand an emergency credit to reinforce the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps. The debate that followed was one of the most vitriolic in France's political history.

On the morning of 30 March, a deputation from the Union républicaine and Gauche républicaine, the two groups which accounted for the bulk of Ferry's support during the undeclared war with China, pleaded with the premier to resign before the debate. Ferry was under little doubt that his administration would fall, but he refused to go without a fight. In the afternoon he entered the chamber amid the disapproving silence of his supporters and a storm of imprecations and insults from his opponents, led by Georges Clemenceau. He had not slept the night before and walked towards the rostrum slowly and gravely, his face pale and anxious, like a condemned man to the scaffold. From the rostrum he gave the Chamber of Deputies the latest news on the military situation in Tonkin and explained the measures he had taken in response. 'We must avenge the check at Lạng Sơn,' he said. 'We must do this not only to secure our hold on Tonkin, but also to safeguard our honour around the world.' Georges Périn, one of Clemenceau's supporters, interjected excitedly. 'Our honour, yes! But who was it that compromised it in the first place?' The Chamber broke into a clamour. Eventually, when he could again make himself heard, Ferry demanded an extraordinary credit of 200 million francs, to be split equally between the army and navy ministries. He went on. 'I cannot go into the details of this expenditure in this forum. We will discuss them further with the scrutiny commission.' Clemenceau shouted scornfully, 'Who will ever believe you?' Ferry implored the deputies not to consider the vote on the credits as a vote of confidence. If they wished, they could overturn his cabinet afterwards and choose a new administration. But for the sake of the French troops in Tonkin, they must first vote to send out more ships and more men. He concluded by formally moving that the credits be voted.

His opponents erupted in anger. Périn yelled 'Don't keep on exploiting the honour of our flag! You've wrapped yourself in our flag for far too long! Enough is enough!' Clemenceau attacked the premier in savage terms. 'We're completely finished with you! We're never going to listen to you again! We're not going to debate the nation's affairs with you again!' The Chamber erupted in applause, and Clemenceau went on. 'We no longer recognise you! We don't want to recognise you!' There was a new burst of applause. 'You're no longer ministers! You all stand accused' — there was a roar of applause from the deputies of both the left and the right, and Clemenceau paused dramatically — 'of high treason! And if the principles of accountability and justice still exist in France, the law will soon give you what you deserve!'

Ferry's opponents demanded immediate discussion of Clemenceau's interpellation. Ferry countered by moving that the vote on the credits should be taken first. Amid scenes of angry turbulence, the deputies voted on Ferry's priority motion. It was defeated by a handsome margin of 306 votes to 149. This defeat spelled the end for his administration. His opponents greeted the result of the vote with howls of delight.

As Ferry sought to leave the Palais Bourbon to return to the Elysée Palace, he had to run the gauntlet of a furious crowd of demonstrators gathered together by Paul de Cassagnac. The demonstrators yelled abuse at the fallen premier, jabbing their fingers towards him violently. 'Down with Ferry! Death to Ferry!' Ferry's friends hustled him past this baying pack. But there was worse to come. The news of the cabinet's fall had gone round Paris like wildfire, and in front of the palais Bourbon an excited mob, estimated by journalists at around 20,000 people, thronged the pont de la Concorde. This crowd had been whipped up to a frenzy by agitators from the far-right parties, and at the sight of Ferry it gave tongue. 'Down with Ferry! Throw him in the Seine! Death to the Tonkinese!' No French premier had ever before faced such an outpouring of hatred.

Aftermath

The immediate consequence of the Tonkin Affair was to bring about a rapid end to the Sino-French War. The sudden and ignominious end of Jules Ferry's second administration removed the remaining obstacles to a peace settlement between France and China. Ferry's successor, Charles de Freycinet, promptly concluded peace with China. The Chinese government agreed to implement the Tientsin Accord of 11 May 1884, implicitly recognising the French protectorate over Tonkin, and the French government dropped its longstanding demand for an indemnity for the Bắc Lệ ambush. A peace protocol ending hostilities was signed on 4 April 1885, and a substantive peace agreement, the Treaty of Tientsin, was signed on 9 June by Li Hongzhang and the French minister Jules Patenôtre des Noyers.

The longer-term effect of the Tonkin Affair was to discredit the supporters within France of colonial expansion. In December 1885, in the so-called 'Tonkin Debate', Henri Brisson's administration was only able to secure fresh credits for the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps by the very narrowest of margins. Jules Ferry would never again serve as premier, and became a figure of popular scorn. The collapse of Ferry's ministry was a major political embarrassment for the proponents of the policy of French colonial expansion first championed in the 1870s by Léon Gambetta. It was not until the early 1890s that French colonial party regained domestic political support.

The consequences to colonial policy stretched beyond Tonkin, or even Paris. Writes one historian of French colonialism in Madagascar, "There was a general desire to have done with other colonial expeditions still in progress."

That said, the forces which drove French colonial expansion were little slowed by loss of political popularity. French Indochina was consolidated under a single administration just two years later, while in Africa, military commanders like Joseph Gallieni and Louis Archinard continually pressured local states, regardless of the political climate in Paris. Large trading houses, such as Maurel and Prom company, continued to expand their overseas operations, and demand military support for this expansion. The formal creation in 1894 of the French Colonial Union, a political pressure group funded by such interests, marked the end of the post-Tonkin climate in Paris, which was, as such, short-lived.

See also

Notes

- Thomazi, 259

- Thomazi, 261

- Le Journal des débats, 31 March 1885; Reclus, 334–49; Thomazi, 262

- Lung Chang, 369–71; Thomazi, 261–2

- See: Ageron, C.R., France coloniale ou parti colonial. Paris, (1978)

- Deschamps, Hubert. Madagascar and France, in Desmond J. Clark, Roland Anthony Oliver, A. D. Roberts, John Donnelly Fage eds, The Cambridge History of Africa, The Cambridge History of Africa (1975) p.525

References

- Billot, A., L'affaire du Tonkin: histoire diplomatique du l'établissement de notre protectorat sur l'Annam et de notre conflit avec la Chine, 1882–1885, par un diplomate (Paris, 1888)

- Harmant, J., La vérité sur la retraite de Lang-Son (Paris, 1892)

- Lecomte, J., Lang-Son: combats, retraite et négociations (Paris, 1895)

- Lung Chang , Yueh-nan yu Chung-fa chan-cheng (Taipei, 1993)

- Reclus, M., Jules Ferry, 1832–1893 (Paris, 1886)

- Thomazi, A., La conquête de l'Indochine (Paris, 1934)

| Sino-French War | |

|---|---|

| Background | |

| Military and political developments |

|

| French personalities | |

| Chinese personalities | |

| Armies and fleets | |