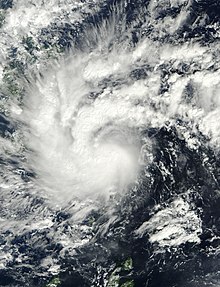

Severe Tropical Storm Washi approaching Mindanao on December 16 Severe Tropical Storm Washi approaching Mindanao on December 16 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | December 13, 2011 |

| Dissipated | December 19, 2011 |

| Severe tropical storm | |

| 10-minute sustained (JMA) | |

| Highest winds | 95 km/h (60 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 992 hPa (mbar); 29.29 inHg |

| Tropical storm | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 95 km/h (60 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 985 hPa (mbar); 29.09 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 1,292–2,546 |

| Injuries | 6,071 |

| Missing | 1,049 |

| Damage | $97.8 million (2011 USD) |

| Areas affected | Caroline Islands, Philippines |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2011 Pacific typhoon season | |

Severe Tropical Storm Washi, known in the Philippines as Severe Tropical Storm Sendong, was a late-season tropical cyclone that caused around 1,200 to 2,500 deaths and catastrophic damage in the Philippines in late 2011. Washi made landfall over Mindanao, a major region in the Philippines, on December 16. Washi weakened slightly after passing Mindanao, but regained strength in the Sulu Sea, and made landfall again over Palawan on December 17.

Meteorological history

Map key Saffir–Simpson scale Tropical depression (≤38 mph, ≤62 km/h)

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown Storm type

Tropical cyclone

Tropical cyclone  Subtropical cyclone

Subtropical cyclone  Extratropical cyclone, remnant low, tropical disturbance, or monsoon depression

Extratropical cyclone, remnant low, tropical disturbance, or monsoon depression On December 12, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) noted that a developing area of low pressure had persisted about 945 km (585 mi) south-southeast of Guam. Situated along the southern edge of a subtropical ridge, the system tracked steadily westward towards the Philippines. Located within a region of good diffluence and moderate wind shear, deep convection was able to maintain itself over the circulation. Development of banding features and improvement of outflow indicated strengthening was likely. Further development over the following day prompted the JTWC to issue a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert early on December 13. Less than six hours later, both the JTWC and the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) classified the system as a tropical depression, with the former assigning the identifier 27W. Maintaining a westward track, the depression was forecast to intensify slowly over the following three days. For much of December 13, a slight increase in shear displaced thunderstorm activity from the center of the depression, delaying intensification. By December 14, convection redeveloped over the low and the JTWC subsequently assessed the system to have attained tropical storm status.

Early on December 15, the system crossed west of 135°E and entered the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration's (PAGASA) area of responsibility. Upon doing so, PAGASA began issuing advisories and assigned the cyclone with the local name Sendong. Shortly thereafter, the storm passed close to or over Palau. By 0600 UTC, the JMA upgraded the system to tropical storm status, at which time they assigned it with the name Washi. Maintaining a rapid westward track, Washi slowly became more organized, with low-level inflow improving during the latter part of December 15. On December 16, Washi reached its peak strength as a severe tropical storm and made its first landfall along the east coast of Mindanao.

After passing Mindanao, Washi weakened due to land interaction, but the storm quickly regained its strength, in the Sulu Sea. Late on December 17, Washi crossed Palawan and arrived in the South China Sea, and the system moved out of the PAR on December 18. Washi weakened to a tropical depression and dissipated on December 19, because of cool, dry air, in association with the Northeast Monsoon.

Impact

Across the Cagayan de Oro river basin, a localized heavy rain event occurred during Tropical Storm Washi's passage. Onshore flow from Macajalar Bay, which the Cagayan de Oro river drains into, ran into the steep terrain of Mount Makaturing, Mount Kalatungan, and Mount Kitanglad, resulting in orographic enhancement of precipitation. A weather station in Capehan located along the Bubunawan river, a tributary of the Cagayan de Oro river, recorded 475 mm (18.7 in) over a 24‑hour span. The rainfall event itself amounted to a 1-in-20 year event for much of Misamis Oriental. In the span of 24 hours, 180.9 mm (7.12 in) of rain fell at Lumbia which equates to more than 60 percent of their average December precipitation. Estimates from the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission jointly run by NASA and JAXA indicated that accumulations around the Cagayan de Oro river exceeded 400 mm (16 in). Observations from Talakag captured the sheer intensity of rainfall associated with Washi, with hourly accumulations peaking at 60.6 mm (2.39 in). Similar amounts, though less anomalous in magnitude, fell farther east on Mindanao. Satellite estimates indicated accumulations of 200 to 250 mm (7.9 to 9.8 in) along coastal areas near where Washi made landfall. A total of 180.4 mm (7.10 in) was observed in Hinatuan.

Starting in tributaries and later reaching the main Cagayan de Oro, Iponan, and Mandulog rivers, flash flooding manifested at a dramatic pace. In some locations, flood waters rose by 3.3 m (11 ft) in less than an hour. Alongside the effects from rainfall, high tide at Macajalar Bay further enhanced the flood event and allowed water to inundate areas that would have otherwise safe at low tide. The rivers crested at 7 to 9 m (23 to 30 ft), amounting to a 75-year flood event in some areas, with catastrophic results. This was also far higher than the previous flood event following Tropical Depression Auring in January 2009. Located outside the main "typhoon belt," residents in the affected areas suffered from a false sense of security with tropical cyclone related disasters. Flooding from the rivers struck at approximately 2:30 a.m. local time, when most people were asleep and unable to hear warnings from PAGASA. Hardest hit were the cities of Cagayan de Oro and Iligan where tremendous loss of life occurred. Within Cagayan de Oro, the barangay of Balulang, Carmen and Macasandig was virtually wiped out. Between the two cities, 1,147 people lost their lives while a further 1,993 sustained injury. Residents affected by these flood waters were forced to seek refuge on their roofs amidst 90 km/h (55 mph) winds. The mayor of Iligan regarded the floods as the worst in the city's history.

Throughout the affected areas, nearly 40,000 homes were damaged of which 11,463 were destroyed. Nearly 700,000 people were affected by the storm. Total casualties attributed to the event are uncertain, with the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council's final report in February 2012 stating 1,268 fatalities, 181 people missing, and 6,071 injuries. A later report by the World Meteorological Organization in December of that year indicated 1,292 deaths, 1,049 missing, and 2,002 injured. The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies stated a total of 2,546 deaths in their final report on August 21, 2013. Damage directly related to the storm amounted to ₱ 2.068 billion (2012 PhP, $48.4 million USD). Over half of the damage was due to damaged roads and bridges. Total socio-economic losses amounted to US$97.8 million.

Highest Public Storm Warning Signal

| PSWS# | Luzon | Visayas | Mindanao |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Palawan | Southern Leyte, Bohol, Southern portion of Cebu, Southern portion of Negros Oriental, Southern Portion of Negros Occidental, Siquijor | Surigao del Norte incl. Siargao Island, Surigao del Sur, Dinagat Province, Agusan del Norte, Agusan del Sur, Davao del Norte, Davao Oriental, Samal Island, Lanao del Norte, Lanao del Sur, Misamis Occidental, Misamis Oriental, Zamboanga del Norte, Zamboanga del Sur, North Cotabato, Compostela Valley, Camiguin, Bukidnon, Maguindanao, Camotes Islands |

| 1 | Masbate, Sorsogon, Ticao Islands, Cuyo Islands, Coron | Eastern Samar, Western portion of Samar, Northern portion of Leyte, Rest of Cebu, Rest of Negros Oriental, Rest of Negros Occidental, Capiz, Antique, Aklan, Iloilo, Guimaras | None |

Aftermath

| Rank | Storm | Season | Fatalities | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yolanda (Haiyan) | 2013 | 6,300 | |

| 2 | Uring (Thelma) | 1991 | 5,101–8,000 | |

| 3 | Pablo (Bopha) | 2012 | 1,901 | |

| 4 | "Angela" | 1867 | 1,800 | |

| 5 | Winnie | 2004 | 1,593 | |

| 6 | "October 1897" | 1897 | 1,500 | |

| 7 | Nitang (Ike) | 1984 | 1,426 | |

| 8 | Reming (Durian) | 2006 | 1,399 | |

| 9 | Frank (Fengshen) | 2008 | 1,371 | |

| 10 | Sendong (Washi) | 2011 | 1,257 |

A massive relief operation involving the evacuation of 100,000 people occurred on the morning of December 17, 2011. Approximately 20,000 soldiers were mobilized to assist in recovery efforts and evacuations. The Philippine Coast Guard was dispatched to search for missing people after villages were reported to have been swept out to sea. Sixty people were rescued off the coast of El Salvador, Misamis Oriental and another 120 in the waters near Opol township. President Benigno Aquino III visited Cagayan de Oro and Iligan on December 20, 2011, and declared a state of national calamity in the affected provinces. The President also appealed to its citizens to help the victims in their way of celebrating Christmas in his Christmas Message.

A leptospirosis outbreak in the immediate aftermath infected more than 400 people and killed 22. Additional fatalities from suicide took place in evacuation centers, though exact numbers are unknown.

In the three years following Washi, ₱2.57 billion (US$58 million) was allocated to build 30,438 shelters, designed to withstand winds of 220 km/h (140 mph), in eight regions. Less than half of this total had been built by December 2014, though construction in Cagayan de Oro and Iligan was largely complete. The storm prompted a shift in settlement patterns in Cagayan de Oro, with residents moving away from the areas along the Cagayan River in favor of upland areas.

International aid and assistance

Overseas humanitarian aid was sent to victims of Washi in the Philippines.

The Australian government provided A$1 million (US$1.01 million) in financial aid.

The Danish government provided 300,000 DKK (US$53,000) in emergency funds for relief items such as food, water, sanitation materials, mattresses and blankets.

The European Commission allocated €3 million ($3.9 million) to provide emergency relief to tens of thousands of people affected by the storm.

The French Government provided €50,000 (US$65,000) in emergency funds.

The Government of Indonesia provided $50,000 in financial aid and offered to send search and rescue teams and medical teams.

The Japanese government provided 25 million yen (US$320,000) worth of relief goods, such as water tanks and generators, for victims of the storm.

The Government of Malaysia provided $100,000 in financial assistance for relief and rehabilitation.

The Chinese government provided $1.1 million in financial aid.

The Government of Singapore provided S$50,000 (US$39,000) in funds and S$27,800 (US$22,000) worth of relief goods.

The Government of South Korea provided $500,000 in financial aid.

Six members of the Swiss Humanitarian Aid Unit were sent to Mindanao to ensure access to clean drinking water.

The British Red Cross provided £140,000 (US$220,000) in funds to support relief efforts.

On December 21, the United Nations Emergency Relief Agency released $3 million in funds to improve water and sanitation. On December 22, the United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs announced a plan to raise $26.8 million in aid for victims of Severe Tropical Storm Washi. United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon sympathized with the Philippine Government and stated "the would extend whatever help is needed by those who were affected by the disaster." The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees also pledged to send 42 metric tons of aid to the country. The United Nations Children's Fund also appealed for $4.2 million to be sent to the Philippines.

The United States provided $100,000 in funds to support relief efforts. The country's ambassador, Harry K. Thomas Jr., expressed his "heartfelt condolences and sympathies" to those affected by the storm. Immediate assistance was to be provided by the United States Agency for International Development's Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance. Non-food items such as hygiene kits, water purification tablets, and containers were to be sent to the Philippines.

Retirement

Due to its high death toll, PAGASA announced that the name, Sendong, would be retired from their tropical cyclone naming lists. In June 2012, PAGASA selected the name Sarah to replace Sendong for the 2015 season. However, due to fewer tropical cyclones entering the area that season, it was first used only in the 2019 season.

In February 2012, the ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee announced that Washi would also be retired from its naming lists and was replaced with the name Hato. But the name Hato was also retired in 2017 and was replaced with Yamaneko, which was first used in the 2022 season.

See also

- 2011 Southeast Asian floods

- Other Philippine tropical cyclones that have claimed more than 1,000 lives

- Typhoon Bopha (Pablo, 2012)

- Typhoon Fengshen (Frank, 2008)

- Typhoon Durian (Reming, 2006)

- Tropical Depression Winnie, 2004

- Tropical Storm Thelma (Uring, 1991)

- Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda, 2013), deadliest tropical cyclone to strike the Philippines in recent recorded history

- Other significant Philippine tropical cyclones

- Typhoon Angela (Rosing, 1995)

- Typhoon Ketsana (Ondoy, 2009)

- Typhoon Tembin (Vinta, 2017) – made landfall in a similar area 6 years later

- Typhoon Rai (Odette, 2021) – a powerful tropical cyclone that affected similar areas exactly 10 years later

- Tropical Storm Nalgae (Paeng, 2022) – a deadly and very large tropical storm that also caused flash flooding in Mindanao

Notes

- The death and missing columns includes deaths caused by Typhoon Fengshen (Frank), in the MV Princess of the Stars disaster.

References

- ^ Olavo Rasquinho; Jae Hyun Shim; Yun Tae Kim; Jae Chan Ahn; Chi Hun Lee; In Sung Jung; Gmma Dalena; Preminda Joseph Fernando; Susan R. Espinueva; Socrates F. Paat Jr.; Nivagine Nievares & Tess Pajarillo (December 2012). Assessment Report of the Damages Caused by Tropical Storm Washi (PDF) (Report). ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee. ISBN 978-99965-817-6-2. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ^ Emergency appeal final report - Philippines: Tropical Storm Washi (PDF) (Report). International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. August 21, 2013. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ^ Final Report on the Effects and Emergency Management re Tropical Storm "Sendong" (Washi) (PDF) (Report). National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council. February 10, 2012. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- "Significant Tropical Weather Outlook for the Western and South Pacific Oceans". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. United States Navy. December 12, 2011. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- "Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. United States Navy. December 13, 2011. Archived from the original on October 21, 2011. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- "High Seas Forecast". Japan Meteorological Agency. December 13, 2011. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- "Tropical Depression 27W Advisory Number 001". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. United States Navy. December 13, 2011. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- "Tropical Storm 27W Advisory Number 005". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. United States Navy. December 14, 2011. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- "Tropical Depression Sendong Advisory One". Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration. December 15, 2011. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved December 24, 2011.

- "Tropical Depression 27W Advisory Number 008". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. United States Navy. December 15, 2011. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved December 24, 2011.

- "Tropical Storm Washi Tropical Cyclone Advisory". Japan Meteorological Agency. December 15, 2011. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved December 24, 2011.

- "Tropical Storm 27W (Washi) Advisory Number 011". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. United States Navy. December 15, 2011. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved December 24, 2011.

- Initial Assessment of the Development of Tropical Storm Sendong (Washi) over the Philippines (PDF) (Report). DHI Water & Environment. December 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ^ Rob Gutro; Steve Lang; Zhong Liu & Hal Pierce (December 21, 2011). "Hurricane Season 2011: Tropical Storm Washi (Western North Pacific Ocean)". NASA. Archived from the original on April 30, 2015. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- "Storm-triggered floods ravage southern Philippines, kill at least 436". The Washington Post. Associated Press. December 17, 2011. Archived from the original on December 22, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ "Hundreds die as tropical storm Washi sweeps across Philippines". The Telegraph. Associated Press. December 17, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- Padua, David M (2011). "Tropical Cyclone Logs: Sendong (Washi) 2011". Typhoon 2000. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- Ramos, Benito T. Final Report on the Effects and Emergency Management re Tropical Storm "Sendong" (Washi) (PDF) (Report). National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 16, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- Del Rosario, Eduardo D (August 9, 2011). Final Report on Typhoon "Yolanda" (Haiyan) (PDF) (Report). Philippine National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council. pp. 77–148. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ Alojado, Dominic (2015). Worst typhoons of the Philippines (1947-2014) (PDF) (Report). Weather Philippines. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ^ "10 Worst Typhoons that Went Down in Philippine History". M2Comms. August 3, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- Lotilla, Raphael (November 20, 2013). "Flashback: 1897, Leyte and a strong typhoon". Rappler. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- "Deadliest typhoons in the Philippines". ABS-CBNNews. November 8, 2013. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- Padua, David M (June 10, 2011). "Tropical Cyclone Logs: Fengshen (Frank)". Typhoon 2000. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- Rabonza, Glenn J. (July 31, 2008). Situation Report No. 33 on the Effects of Typhoon "Frank"(Fengshen) (PDF) (Report). National Disaster Coordinating Council (National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Center). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- 2011 Top 10 Philippine Destructive Tropical Cyclones. Government of the Philippines (Report). January 6, 2012. ReliefWeb. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- "Storms pound Philippines in the thick of night, kill at least 436". NBC News. December 17, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- Sun.Star: Aquino declares state of national calamity

- "PNoy airs Christmas aid call for Sendong victims". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

- "More than 12,700 shelter units built for survivors of 'Sendong' despite challenges". Government of the Philippines. ReliefWeb. December 29, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- Gallardo, Froilan. "Survivors remember Sendong tragedy that changed Cagayan de Oro". Rappler. Retrieved December 17, 2024.

- ^ Noemi M. Gonzales & Johanna Paola D. Poblete (December 22, 2011). "UN issues $28.6-million international appeal for victims". BusinessWorld. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- "Denmark sends emergency aid to disaster areas in the Philippines". ScandAsia. December 23, 2011. Archived from the original on January 30, 2012. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- "EC mobilizes funds to help 'Sendong' victims". Philippine Daily Inquirer. December 23, 2011. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- ^ Roy C. Mabasa (December 22, 2011). "UN launches revised aid program". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- "Switzerland sends experts to the Philippine disaster area". Government of Switzerland. ReliefWeb. December 22, 2011. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- "British Red Cross sends funds to support typhoon stricken Philippines". British Red Cross. ReliefWeb. December 22, 2011. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- "$4.2 million UNICEF appeal for Philippine flood victims". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Agence France-Presse. December 20, 2011. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- "U.S. provides aid to support Tropical Storm Sendong relief efforts". United States Department of State. ReliefWeb. December 22, 2011. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- "Government will no longer use Sendong to name typhoons". Sun Star Manila. December 23, 2011. Archived from the original on August 4, 2013. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

- "Forty-Fourth Session of Typhoon Committee" (PDF). Typhoon Committee. February 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

External links

- JMA General Information of Severe Tropical Storm Washi (1121) from Digital Typhoon

- RSMC Tokyo - Typhoon Center

- Best Track Data of Severe Tropical Storm Washi (1121) (in Japanese)

- Best Track Data (Graphics) of Severe Tropical Storm Washi (1121)

- Best Track Data (Text)

- JTWC Best Track Data Archived February 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine of Tropical Storm 27W (Washi)

- 27W.WASHI from the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory

| Retired Pacific typhoon names | |

|---|---|

| Pre-2000s | |

| 2000s | |

| 2010s |

|

| 2020s | |

| Typhoon names retired by PAGASA | |

|---|---|

| 1960s | |

| 1970s | |

| 1980s | |

| 1990s | |

| 2000s | |

| 2010s | |

| 2020s | |

| Tropical cyclones of the 2011 Pacific typhoon season | ||

|---|---|---|

| TD01W TDAmang TSAere VITYSongda TDTD TSSarika TDTD TSHaima STSMeari TDGoring VSTYMa-on TSTokage TDTD TDTD STSNock-ten VSTYMuifa TDLando STSMerbok TDTD TD13W TDTD TDTD VSTYNanmadol STSTalas TSNoru TSKulap VSTYRoke TYSonca TDTD TYNesat TSHaitang VSTYNalgae TSBanyan TDTD TD24W TD25W TD26W STSWashi TDTD TDTD | |