| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | USS Keokuk |

| Namesake | City of Keokuk |

| Ordered | March 1862 |

| Builder | Charles W. Whitney, New York City |

| Laid down | 1862 |

| Launched | December 6, 1862 |

| Commissioned | March 1863 |

| Fate | Sunk, April 8, 1863 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Casemate ironclad |

| Displacement | 677 long tons (688 t) |

| Length | 159 ft 6 in (48.62 m) |

| Beam | 36 ft (11 m) |

| Draft | 8 ft 6 in (2.59 m) |

| Propulsion | Two 250 hp two-cylinder steam engines, 2 screws of 7-foot, 6-inch diameter |

| Speed | 9 knots (17 km/h; 10 mph) |

| Complement | 92 officers and men |

| Armament |

|

| Armor | Alternating horizontal 1 in x 4 in iron bars and yellow pine slats, sheathed with layers of 1/2 in iron plates with a total hull thickness of 5.75 in (146 mm) |

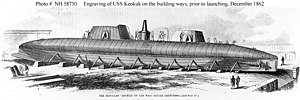

USS Keokuk was an experimental ironclad screw steamer of the United States Navy named for the city of Keokuk, Iowa. She was laid down in New York City by designer Charles W. Whitney at J.S. Underhill Shipbuilders, at the head of 11th Street. She was originally named Moodna (sometimes incorrectly spelled "Woodna"), but was renamed while under construction, launched in December 1862 sponsored by Mrs. C. W. Whitney, wife of the builder, and commissioned in early March 1863 with Commander Alexander C. Rhind in command.

Design

Keokuk was one of the first warships to be of completely iron construction, with wood used only for deck planks and filler in the armor cladding. Her hull construction consisted of five iron box keelsons and one hundred 1-inch-thick (some sources report the thickness as 3/4 inch) by 4-inch-deep iron frames spaced 18 inches between centers. The frames included integral iron cross beams for the decks, with no transverse wood timbers as used on the Monitor. Her bow and stern sections were flooding spaces to allow raising and lowering her waterline.

Her two stationary, conical gun towers, each pierced with three gun ports, housed one 11-inch Dahlgren shell gun each on a shortened and rounded rotating wooden slide carriage (the tower shape often causing her to be mistaken for a double-turreted monitor). Her tower and casemate armor was made up from 1-inch-thick by 4-inch-deep horizontal iron bars alternating with planks of yellow pine of the same dimensions, sheathed with layers of overlapping, flush-bolted 1⁄2-inch rolled iron plates. A total thickness of this composite armor, including the hull skin proper, was 5.75 inches (146 mm). The deck was made of 5-inch wood planks overlaid with 1⁄2-inch-thick iron plate. She had two twin-cylinder main propulsion engines, each 250 hp. In total, Keokuk had nine steam engines providing power to various systems.

Service history

| This section needs expansion with: history for 1863. You can help by adding to it. (February 2013) |

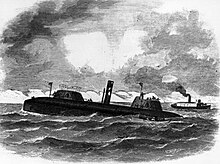

The new ironclad departed New York on March 11, 1863 and steamed south to join the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron for the attack on Charleston, South Carolina, and arrived at Newport News, Virginia, two days later. She got underway again on March 17 but returned to Hampton Roads for repairs when her port propeller became fouled in a buoy anchor line. She stood out of Hampton Roads again on March 22 and arrived at Port Royal, South Carolina on March 26. A soldier who saw the Keokuk wrote of her in a letter home: "...The iron clad battery Keokuk steamed by me yesterday and I have heard that she was bound to Charleston S.C. It was a curious looking affair I assure you it had two turrets with two guns in each. It looked a little like this but of course I am not an artist..."

As the day of attack on Charleston approached, Keokuk and USS Bibb were busy laying buoys to guide Rear Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont's ironclad flotilla, which included USS New Ironsides, seven monitors (Weehawken, Passaic, Montauk, Patapsco, Catskill, Nantucket, and Nahant), and Keokuk, into the strongly fortified Confederate harbor. The Union ships crossed the Stono Bar on April 6 but were prevented from attacking that day by hazy weather which obscured targets and blinded pilots.

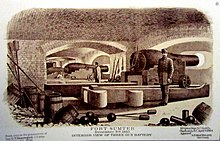

The First Battle of Charleston Harbor began at noon on April 7, but difficulties in clearing torpedoes from the path of Du Pont's ironclads slowed their progress. Shortly after 3 p.m., they came within range of Fort Moultrie and Fort Sumter; and the battle began. Southern obstructions and a strong flood tide made the ironclads virtually unmanageable, while accurate fire from the forts played upon them at will. With the Union formation scrambled, Keokuk was compelled to run ahead of crippled USS Nahant to avoid her in the narrow channel after Nahant's pilot was killed and helmsman wounded by a Confederate shot striking the pilothouse. This brought her less than 600 yards (550 m) from Fort Sumter, where she remained for half an hour receiving the undivided attention of the Confederate cannons.

Keokuk was struck by about ninety projectiles, many of which hit at or below her waterline. Commander Rhind reported his ship as being hit by a combination of solid shot, bolts, and possibly heated shot. As predicted by her chief engineer, her thin composite armor was completely inadequate to protect her from this onslaught and she was "completely riddled" in the words of Commander Rhind. However, she was able to withdraw under her own power and anchor out of range, thanks in part to the skills of her Black pilot, Robert Smalls, a former slave and pilot of CSS Planter. Her crew kept her afloat through the night, but when a breeze came up on the morning of April 8, 1863, Keokuk began taking on more water, filled rapidly, and sank off Morris Island. She had given one month of commissioned service. One of Keokuk's sailors, Quartermaster Robert Anderson, was awarded the Medal of Honor in part for his actions during the battle. In all, 14 of Keokuk's crew were injured in the battle, including Captain Rhind with a contusion to his leg. Acting Ensign Mackintosh, one of the gun captains, later died from his wounds.

Salvage of Keokuk guns

A Federal survey of the wreck shortly after the battle determined that the Keokuk could not be refloated or destroyed, as she was almost completely filled with sand. The two 11-inch Dahlgren guns could be easily replaced from stockpiles and were abandoned as unsalvageable.

To Confederate forces, these two guns represented an opportunity to obtain badly needed artillery. The Confederacy possessed only 150 to 200 naval and coastal defense guns, none of them as large as the sunken Dahlgrens. P.G.T. Beauregard, commander of the Charleston defenses, authorized an immediate salvage operation led by a civilian, Adolphus W. LaCoste. A modified lightship, Rattlesnake Shoals, was towed into place as a salvage platform. To avoid attracting the attention of Union forces, work was done at night, during low tide, with the Confederate ironclads Palmetto State and Chicora providing protection. The Union did not suspect this activity until it was announced in the Charleston Mercury after the guns were recovered.

The Keokuk guns served the Confederacy for the remainder of the war. One was destroyed, probably during the evacuation of Charleston in 1865. The other gun tube can still be seen on the Charleston waterfront at White Point Garden, mounted on an incorrect iron fortress carriage. In the image, the Keokuk gun is in the background.

Notes

- Canney,

- Scientific American, December 20, 1862

- Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events of the year: 1862. New York: D. Appleton & Company. 1863. p. 613.

- Jack S Powers in a letter to Nellie Williams of Framingham Massachusetts, on board the Union transport DeWitt Clinton, Fort Monroe Virginia, March 23, 1863

- "Civil War Medal of Honor Recipients (A–L)". Medal of Honor Citations. U.S. Army Center of Military History. August 6, 2009. Archived from the original on September 2, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- New York Times, Battle of Charleston, April 12, 1863

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, p. 208.

- Poore, Devin (May 24, 2013). "Raiding the Keoku". New York Times. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

References

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.- Coker, P. C., III. Charleston's Maritime Heritage, 1670–1865: An Illustrated History. Charleston, S.C.: Coker-Craft, 1987. 314 pp.

- Browning, Robert M. Jr., Success is all that was expected: the South Atlantic blockading squadron during the Civil War. Washington, D.C. : Brassey’s, 2002. ISBN 1-57488-514-6

- Canney, Donald L. (1993). The Old Steam Navy: The Ironclads, 1842–1885. Vol. 2. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-586-8.

- Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Olmstead, Edwin; Stark, Wayne E.; Tucker, Spencer C. (1997). The Big Guns: Civil War Siege, Seacoast, and Naval Cannon. Alexandria Bay, New York: Museum Restoration Service. ISBN 0-88855-012-X.

- "Keokuk". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command (NH&HC). Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (2006). Civil War Navies 1855–1883. The U.S. Navy Warship Series. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-97870-X.

External links

Media related to USS Keokuk (ship, 1862) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to USS Keokuk (ship, 1862) at Wikimedia Commons- Photo gallery at Naval Historical Center

32°41′36″N 79°52′19″W / 32.69333°N 79.87194°W / 32.69333; -79.87194

| Ironclads of the United States | |

|---|---|

| Coastal monitors | |

| River and harbor monitors | |

| Ocean-going monitors | |

| Riverine casemate ironclads | |

| Ocean-going casemate ironclads | |

| Commissioned ironclads | |

| Never-commissioned ironclads | |

| Miscellaneous ironclads | |