| Vértesboglár | |

|---|---|

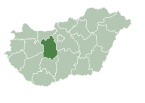

Location of Fejér county in Hungary Location of Fejér county in Hungary | |

| |

| Coordinates: 47°25′46″N 18°31′22″E / 47.42954°N 18.52284°E / 47.42954; 18.52284 | |

| Country | |

| County | Fejér |

| Area | |

| • Total | 23.21 km (8.96 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 945 |

| • Density | 40.71/km (105.4/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 8085 |

| Area code | 22 |

| Website | www |

Vértesboglár (German: Boglar) is a village in Fejér county, in the Járás (district) of Bicske, Hungary.

History

Vértesboglár and its surroundings were already inhabited by the Romans, as evidenced by the finds and the traces of the Roman road crossing the settlement.

The name of Boglár (Al- and Felboglár) - upper and lower Boglár - was already mentioned in the documents before 1187 as a royal estate. It was written as Boclar in 1193, Boklar in 1221, Olboklar (Alboglár) (lower Boglár) in 1311, and Boklár in 1339.

Medieval were found in Alkotmány Street 48. During the period of Turkish subjugation/occupation, the village was depopulated. It belonged to Csákvár, and its inhabitants cultivated the lands belonging to the destroyed settlement. According to the evidence of the papal rule, the counts of Eszterházy paid 12 Forints annually for the use of the meadow. In 1696, it was only recorded that Boglárpuszta consisted of a forest suitable for logging and a mowing field.

In 1760 Ferenc Eszterházy orchestrated its resettlement. He had a vision of the village being inhabited by "God-fearing, peaceful, and just-minded" pioneers who would cultivate the land of Boglárpuszta. These settlers were granted three years of freedom (from paying taxes) during which they were tasked with building houses, clearing forests, tilling the land, and establishing vineyards. The village attracted 35 serfs and 22 leaseholders who arrived from the Eszterházy estate in Tata and the Black Forest (Schwarzwald) of Bavaria.

As the years passed, the village's population continued to grow. By 1768, it was already home to 129 serf households. The settlers' diligent work is evident on the earliest military maps, where they had largely cleared the forests, created pastures, cultivated fields, and established extensive vineyards. The village's progress also extended to religious and educational development. In 1761, the parish was established, and in 1762, a chapel was arranged within one of the rooms of the parish. The Roman Catholic church, built in 1810 with the support of the Eszterházy family, stands as a testament to their commitment.

The beginnings of public education date back to 1770, with 40 boys and girls attending school. A decade later, the number of students had risen to 95. A two-room house was constructed for the teacher, with one of the rooms serving as a classroom.

The predominantly German-speaking population of Vértesboglár felt the significant effects of the 1848 serf emancipation. In the autumn of 1848, the village's residents took up arms to defend their village, with the Roman Catholic parish priest Miklós Streith and chaplain Mór König playing key roles in the local revolutionary committee. Streith proclaimed the Declaration of Independence from the pulpit and called upon his followers to rise up in June 1849. The imperial forces arrested both priests, leading to the execution of Miklós Streith and a 15-year prison sentence for Mór König.

By the mid-19th century, Vértesboglár was described as a German village in Székes-Fejér County with predominantly Catholic residents. The village was involved in winemaking, and it was noted for its connection to Count Miklós Eszterházy.

Following the serf emancipation and land consolidation in the early 1860s, Vértesboglár had 157 peasant families primarily engaged in agriculture. The village was home to small landowners, tenant farmers, vineyard cultivators, and artisans who catered to local needs. Notable handicrafts included the production of wooden-soled shoes known as "klumpák." The village also thrived with vine cultivation, producing an average of 2,100 "akó" of wine each year, alongside fruitful gardens. The urban area expanded with the construction of new houses and cellars, and connections to nearby towns were improved.

At the turn of the century, the Eszterházy family owned more than half of the village's land, and the population had reached 1,183 individuals with 220 residential houses. A predominantly German-speaking population was observed, with Hungarian speakers mainly among the servants.

World War I brought significant challenges as men were drafted into the military, leaving women responsible for supporting their families. A hundred men from the village were mobilized, and 45 of them sacrificed their lives on the battlefields and in prisoner of war camps. These difficulties were exacerbated by the limited supplies available in the village's two shops, leading women to travel to neighboring towns like Bicske or Pest in search of essential goods.

Eszterházy's journal sheds light on the nationalization during the Hungarian Soviet Republic, noting the excitement and pride of the masses as they believed they had acquired land. The direct evidence of this period is the stamp of the "Workers' and Peasants' Council Directorate of Vértesboglár." After the fall of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, the local directorate members were replaced, and the previous order was reinstated. Boglár experienced infrastructural development, with regular bus routes between Csákvár and Bicske alongside railways. The village had postal, telegraph, and telephone services. Social and economic associations were established, including a fire brigade, youth association, choir, milk cooperative, credit union, and consumer cooperative.

Between the two World Wars, Vértesboglár enjoyed a period of political and economic stability until Hungary's entry into the war in 1941.

The stability of Vértesboglár was disrupted by World War II. After 1945, the majority of the German-speaking residents were forcibly deported from the village. For nearly two centuries, from 1760, they had peacefully lived as Hungarian citizens, but the decisions of the victorious powers of World War II led to the resettlement of 46 families in Germany, replacing them with 141 Hungarian expellees from Slovakia.

In October 1950, a council-based administration system was introduced. During the decades of socialist rule, the village saw the establishment of a general school, a kindergarten, healthcare services, and the creation of a local police office. The end of communism in Hungary resulted in (similarly to other parts of the country) the formation of a local government. This period was a period that brought privatization, meaning that land ownership shifted back to private hands.

Mayors

- 1990–1994: Miss Bauer János born Anna Keilbach (independent)

- 1994–1998: Miss Bauer János born Anna Keilbach (independent)

- 1998–2002: Miss Bauer János born Anna Keilbach (independent)

- 2002–2004: Miss Bauer János born Anna Keilbach (independent)

- 2004–2006: Miss Terézia Orosz (born Genczwein) (independent)

- 2006–2007: Dezső Szabó (independent)

- 2007–2010: István Sztányi (independent)

- 2010–2014: István Sztányi (independent)

- 2014–2019: István Sztányi (independent)

- 2019-től: István Sztányi (independent)

External links

Media related to Vértesboglár at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vértesboglár at Wikimedia Commons- Street map (in Hungarian)

- www

.vertesboglar .hu - www

.civilboglar .hu

References

- ^ "A talu története". www.vertesboglar.hu. Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- ^ Farkas, Gábor. Magyarország megyei kézikönyvei 6.kötet.

- ^ Vértesboglár - A kétszer foglalt mező, retrieved 2023-11-01

- Tafferner, Antal (1941). Vértesboglár: egy hazai német település leirása (in Hungarian).

- "VÉRTESBOGLÁR TELEPÜLÉSKÉPI ARCULATI KÉZIKÖNYVE" (PDF) (in Hungarian).

- "Vértesboglár települési választás eredményei" (txt) (in Hungarian). Nemzeti Választási Iroda. 1990. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- "Vértesboglár települési választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Országos Választási Iroda. 1994-12-11. Retrieved 2020-02-17.

- "Vértesboglár települési választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Országos Választási Iroda. 1998-10-18. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- "Vértesboglár települési választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Országos Választási Iroda. 2002-10-20. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- "Vértesboglár települési időközi választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Nemzeti Választási Iroda. 2004-06-13. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- "Vértesboglár települési választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Országos Választási Iroda. 2006-10-01. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- "Vértesboglár települési időközi választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Nemzeti Választási Iroda. 2007-11-18. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- "Vértesboglár települési választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Országos Választási Iroda. 2010-10-03. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- "Vértesboglár települési választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Nemzeti Választási Iroda. 2014-10-12. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- "Vértesboglár települési választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Nemzeti Választási Iroda. 2019-10-13. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

This Fejér location article is a stub. You can help Misplaced Pages by expanding it. |