| Sound measurements | |

|---|---|

| Characteristic | Symbols |

| Sound pressure | p, SPL, LPA |

| Particle velocity | v, SVL |

| Particle displacement | δ |

| Sound intensity | I, SIL |

| Sound power | P, SWL, LWA |

| Sound energy | W |

| Sound energy density | w |

| Sound exposure | E, SEL |

| Acoustic impedance | Z |

| Audio frequency | AF |

| Transmission loss | TL |

The speed of sound is the distance travelled per unit of time by a sound wave as it propagates through an elastic medium. More simply, the speed of sound is how fast vibrations travel. At 20 °C (68 °F), the speed of sound in air, is about 343 m/s (1,125 ft/s; 1,235 km/h; 767 mph; 667 kn), or 1 km in 2.91 s or one mile in 4.69 s. It depends strongly on temperature as well as the medium through which a sound wave is propagating.

At 0 °C (32 °F), the speed of sound in air is about 331 m/s (1,086 ft/s; 1,192 km/h; 740 mph; 643 kn).

The speed of sound in an ideal gas depends only on its temperature and composition. The speed has a weak dependence on frequency and pressure in ordinary air, deviating slightly from ideal behavior.

In colloquial speech, speed of sound refers to the speed of sound waves in air. However, the speed of sound varies from substance to substance: typically, sound travels most slowly in gases, faster in liquids, and fastest in solids.

For example, while sound travels at 343 m/s in air, it travels at 1481 m/s in water (almost 4.3 times as fast) and at 5120 m/s in iron (almost 15 times as fast). In an exceptionally stiff material such as diamond, sound travels at 12,000 m/s (39,370 ft/s), – about 35 times its speed in air and about the fastest it can travel under normal conditions.

In theory, the speed of sound is actually the speed of vibrations. Sound waves in solids are composed of compression waves (just as in gases and liquids) and a different type of sound wave called a shear wave, which occurs only in solids. Shear waves in solids usually travel at different speeds than compression waves, as exhibited in seismology. The speed of compression waves in solids is determined by the medium's compressibility, shear modulus, and density. The speed of shear waves is determined only by the solid material's shear modulus and density.

In fluid dynamics, the speed of sound in a fluid medium (gas or liquid) is used as a relative measure for the speed of an object moving through the medium. The ratio of the speed of an object to the speed of sound (in the same medium) is called the object's Mach number. Objects moving at speeds greater than the speed of sound (Mach1) are said to be traveling at supersonic speeds.

Earth

In Earth's atmosphere, the speed of sound varies greatly from about 295 m/s (1,060 km/h; 660 mph) at high altitudes to about 355 m/s (1,280 km/h; 790 mph) at high temperatures.

History

Sir Isaac Newton's 1687 Principia includes a computation of the speed of sound in air as 979 feet per second (298 m/s). This is too low by about 15%. The discrepancy is due primarily to neglecting the (then unknown) effect of rapidly fluctuating temperature in a sound wave (in modern terms, sound wave compression and expansion of air is an adiabatic process, not an isothermal process). This error was later rectified by Laplace.

During the 17th century there were several attempts to measure the speed of sound accurately, including attempts by Marin Mersenne in 1630 (1,380 Parisian feet per second), Pierre Gassendi in 1635 (1,473 Parisian feet per second) and Robert Boyle (1,125 Parisian feet per second). In 1709, the Reverend William Derham, Rector of Upminster, published a more accurate measure of the speed of sound, at 1,072 Parisian feet per second. (The Parisian foot was 325 mm. This is longer than the standard "international foot" in common use today, which was officially defined in 1959 as 304.8 mm, making the speed of sound at 20 °C (68 °F) 1,055 Parisian feet per second).

Derham used a telescope from the tower of the church of St. Laurence, Upminster to observe the flash of a distant shotgun being fired, and then measured the time until he heard the gunshot with a half-second pendulum. Measurements were made of gunshots from a number of local landmarks, including North Ockendon church. The distance was known by triangulation, and thus the speed that the sound had travelled was calculated.

Basic concepts

The transmission of sound can be illustrated by using a model consisting of an array of spherical objects interconnected by springs.

In real material terms, the spheres represent the material's molecules and the springs represent the bonds between them. Sound passes through the system by compressing and expanding the springs, transmitting the acoustic energy to neighboring spheres. This helps transmit the energy in-turn to the neighboring sphere's springs (bonds), and so on.

The speed of sound through the model depends on the stiffness/rigidity of the springs, and the mass of the spheres. As long as the spacing of the spheres remains constant, stiffer springs/bonds transmit energy more quickly, while more massive spheres transmit energy more slowly.

In a real material, the stiffness of the springs is known as the "elastic modulus", and the mass corresponds to the material density. Sound will travel more slowly in spongy materials and faster in stiffer ones. Effects like dispersion and reflection can also be understood using this model.

Some textbooks mistakenly state that the speed of sound increases with density. This notion is illustrated by presenting data for three materials, such as air, water, and steel and noting that the speed of sound is higher in the denser materials. But the example fails to take into account that the materials have vastly different compressibility, which more than makes up for the differences in density, which would slow wave speeds in the denser materials. An illustrative example of the two effects is that sound travels only 4.3 times faster in water than air, despite enormous differences in compressibility of the two media. The reason is that the greater density of water, which works to slow sound in water relative to the air, nearly makes up for the compressibility differences in the two media.

For instance, sound will travel 1.59 times faster in nickel than in bronze, due to the greater stiffness of nickel at about the same density. Similarly, sound travels about 1.41 times faster in light hydrogen (protium) gas than in heavy hydrogen (deuterium) gas, since deuterium has similar properties but twice the density. At the same time, "compression-type" sound will travel faster in solids than in liquids, and faster in liquids than in gases, because the solids are more difficult to compress than liquids, while liquids, in turn, are more difficult to compress than gases.

A practical example can be observed in Edinburgh when the "One o'Clock Gun" is fired at the eastern end of Edinburgh Castle. Standing at the base of the western end of the Castle Rock, the sound of the Gun can be heard through the rock, slightly before it arrives by the air route, partly delayed by the slightly longer route. It is particularly effective if a multi-gun salute such as for "The Queen's Birthday" is being fired.

Compression and shear waves

In a gas or liquid, sound consists of compression waves. In solids, waves propagate as two different types. A longitudinal wave is associated with compression and decompression in the direction of travel, and is the same process in gases and liquids, with an analogous compression-type wave in solids. Only compression waves are supported in gases and liquids. An additional type of wave, the transverse wave, also called a shear wave, occurs only in solids because only solids support elastic deformations. It is due to elastic deformation of the medium perpendicular to the direction of wave travel; the direction of shear-deformation is called the "polarization" of this type of wave. In general, transverse waves occur as a pair of orthogonal polarizations.

These different waves (compression waves and the different polarizations of shear waves) may have different speeds at the same frequency. Therefore, they arrive at an observer at different times, an extreme example being an earthquake, where sharp compression waves arrive first and rocking transverse waves seconds later.

The speed of a compression wave in a fluid is determined by the medium's compressibility and density. In solids, the compression waves are analogous to those in fluids, depending on compressibility and density, but with the additional factor of shear modulus which affects compression waves due to off-axis elastic energies which are able to influence effective tension and relaxation in a compression. The speed of shear waves, which can occur only in solids, is determined simply by the solid material's shear modulus and density.

Equations

The speed of sound in mathematical notation is conventionally represented by c, from the Latin celeritas meaning "swiftness".

For fluids in general, the speed of sound c is given by the Newton–Laplace equation: where

- is a coefficient of stiffness, the isentropic bulk modulus (or the modulus of bulk elasticity for gases);

- is the density.

, where is the pressure and the derivative is taken isentropically, that is, at constant entropy s. This is because a sound wave travels so fast that its propagation can be approximated as an adiabatic process, meaning that there isn't enough time, during a pressure cycle of the sound, for significant heat conduction and radiation to occur.

Thus, the speed of sound increases with the stiffness (the resistance of an elastic body to deformation by an applied force) of the material and decreases with an increase in density. For ideal gases, the bulk modulus K is simply the gas pressure multiplied by the dimensionless adiabatic index, which is about 1.4 for air under normal conditions of pressure and temperature.

For general equations of state, if classical mechanics is used, the speed of sound c can be derived as follows:

Consider the sound wave propagating at speed through a pipe aligned with the axis and with a cross-sectional area of . In time interval it moves length . In steady state, the mass flow rate must be the same at the two ends of the tube, therefore the mass flux is constant and . Per Newton's second law, the pressure-gradient force provides the acceleration:

And therefore:

If relativistic effects are important, the speed of sound is calculated from the relativistic Euler equations.

In a non-dispersive medium, the speed of sound is independent of sound frequency, so the speeds of energy transport and sound propagation are the same for all frequencies. Air, a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen, constitutes a non-dispersive medium. However, air does contain a small amount of CO2 which is a dispersive medium, and causes dispersion to air at ultrasonic frequencies (greater than 28 kHz).

In a dispersive medium, the speed of sound is a function of sound frequency, through the dispersion relation. Each frequency component propagates at its own speed, called the phase velocity, while the energy of the disturbance propagates at the group velocity. The same phenomenon occurs with light waves; see optical dispersion for a description.

Dependence on the properties of the medium

The speed of sound is variable and depends on the properties of the substance through which the wave is travelling. In solids, the speed of transverse (or shear) waves depends on the shear deformation under shear stress (called the shear modulus), and the density of the medium. Longitudinal (or compression) waves in solids depend on the same two factors with the addition of a dependence on compressibility.

In fluids, only the medium's compressibility and density are the important factors, since fluids do not transmit shear stresses. In heterogeneous fluids, such as a liquid filled with gas bubbles, the density of the liquid and the compressibility of the gas affect the speed of sound in an additive manner, as demonstrated in the hot chocolate effect.

In gases, adiabatic compressibility is directly related to pressure through the heat capacity ratio (adiabatic index), while pressure and density are inversely related to the temperature and molecular weight, thus making only the completely independent properties of temperature and molecular structure important (heat capacity ratio may be determined by temperature and molecular structure, but simple molecular weight is not sufficient to determine it).

Sound propagates faster in low molecular weight gases such as helium than it does in heavier gases such as xenon. For monatomic gases, the speed of sound is about 75% of the mean speed that the atoms move in that gas.

For a given ideal gas the molecular composition is fixed, and thus the speed of sound depends only on its temperature. At a constant temperature, the gas pressure has no effect on the speed of sound, since the density will increase, and since pressure and density (also proportional to pressure) have equal but opposite effects on the speed of sound, and the two contributions cancel out exactly. In a similar way, compression waves in solids depend both on compressibility and density—just as in liquids—but in gases the density contributes to the compressibility in such a way that some part of each attribute factors out, leaving only a dependence on temperature, molecular weight, and heat capacity ratio which can be independently derived from temperature and molecular composition (see derivations below). Thus, for a single given gas (assuming the molecular weight does not change) and over a small temperature range (for which the heat capacity is relatively constant), the speed of sound becomes dependent on only the temperature of the gas.

In non-ideal gas behavior regimen, for which the Van der Waals gas equation would be used, the proportionality is not exact, and there is a slight dependence of sound velocity on the gas pressure.

Humidity has a small but measurable effect on the speed of sound (causing it to increase by about 0.1%–0.6%), because oxygen and nitrogen molecules of the air are replaced by lighter molecules of water. This is a simple mixing effect.

Altitude variation and implications for atmospheric acoustics

In the Earth's atmosphere, the chief factor affecting the speed of sound is the temperature. For a given ideal gas with constant heat capacity and composition, the speed of sound is dependent solely upon temperature; see § Details below. In such an ideal case, the effects of decreased density and decreased pressure of altitude cancel each other out, save for the residual effect of temperature.

Since temperature (and thus the speed of sound) decreases with increasing altitude up to 11 km, sound is refracted upward, away from listeners on the ground, creating an acoustic shadow at some distance from the source. The decrease of the speed of sound with height is referred to as a negative sound speed gradient.

However, there are variations in this trend above 11 km. In particular, in the stratosphere above about 20 km, the speed of sound increases with height, due to an increase in temperature from heating within the ozone layer. This produces a positive speed of sound gradient in this region. Still another region of positive gradient occurs at very high altitudes, in the thermosphere above 90 km.

Details

Speed of sound in ideal gases and air

For an ideal gas, K (the bulk modulus in equations above, equivalent to C, the coefficient of stiffness in solids) is given by Thus, from the Newton–Laplace equation above, the speed of sound in an ideal gas is given by where

- γ is the adiabatic index also known as the isentropic expansion factor. It is the ratio of the specific heat of a gas at constant pressure to that of a gas at constant volume () and arises because a classical sound wave induces an adiabatic compression, in which the heat of the compression does not have enough time to escape the pressure pulse, and thus contributes to the pressure induced by the compression;

- p is the pressure;

- ρ is the density.

Using the ideal gas law to replace p with nRT/V, and replacing ρ with nM/V, the equation for an ideal gas becomes where

- cideal is the speed of sound in an ideal gas;

- R is the molar gas constant;

- k is the Boltzmann constant;

- γ (gamma) is the adiabatic index. At room temperature, where thermal energy is fully partitioned into rotation (rotations are fully excited) but quantum effects prevent excitation of vibrational modes, the value is 7/5 = 1.400 for diatomic gases (such as oxygen and nitrogen), according to kinetic theory. Gamma is actually experimentally measured over a range from 1.3991 to 1.403 at 0 °C, for air. Gamma is exactly 5/3 = 1.667 for monatomic gases (such as argon) and it is 4/3 = 1.333 for triatomic molecule gases that, like H

2O, are not co-linear (a co-linear triatomic gas such as CO

2 is equivalent to a diatomic gas for our purposes here); - T is the absolute temperature;

- M is the molar mass of the gas. The mean molar mass for dry air is about 0.02897 kg/mol (28.97 g/mol);

- n is the number of moles;

- m is the mass of a single molecule.

This equation applies only when the sound wave is a small perturbation on the ambient condition, and the certain other noted conditions are fulfilled, as noted below. Calculated values for cair have been found to vary slightly from experimentally determined values.

Newton famously considered the speed of sound before most of the development of thermodynamics and so incorrectly used isothermal calculations instead of adiabatic. His result was missing the factor of γ but was otherwise correct.

Numerical substitution of the above values gives the ideal gas approximation of sound velocity for gases, which is accurate at relatively low gas pressures and densities (for air, this includes standard Earth sea-level conditions). Also, for diatomic gases the use of γ = 1.4000 requires that the gas exists in a temperature range high enough that rotational heat capacity is fully excited (i.e., molecular rotation is fully used as a heat energy "partition" or reservoir); but at the same time the temperature must be low enough that molecular vibrational modes contribute no heat capacity (i.e., insignificant heat goes into vibration, as all vibrational quantum modes above the minimum-energy-mode have energies that are too high to be populated by a significant number of molecules at this temperature). For air, these conditions are fulfilled at room temperature, and also temperatures considerably below room temperature (see tables below). See the section on gases in specific heat capacity for a more complete discussion of this phenomenon.

For air, we introduce the shorthand

In addition, we switch to the Celsius temperature θ = T − 273.15 K, which is useful to calculate air speed in the region near 0 °C (273 K). Then, for dry air,

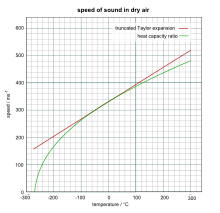

Substituting numerical values and using the ideal diatomic gas value of γ = 1.4000, we have

Finally, Taylor expansion of the remaining square root in yields

A graph comparing results of the two equations is to the right, using the slightly more accurate value of 331.5 m/s (1,088 ft/s) for the speed of sound at 0 °C.

Effects due to wind shear

The speed of sound varies with temperature. Since temperature and sound velocity normally decrease with increasing altitude, sound is refracted upward, away from listeners on the ground, creating an acoustic shadow at some distance from the source. Wind shear of 4 m/(s · km) can produce refraction equal to a typical temperature lapse rate of 7.5 °C/km. Higher values of wind gradient will refract sound downward toward the surface in the downwind direction, eliminating the acoustic shadow on the downwind side. This will increase the audibility of sounds downwind. This downwind refraction effect occurs because there is a wind gradient; the fact that sound is carried along by the wind is not important.

For sound propagation, the exponential variation of wind speed with height can be defined as follows: where

- U(h) is the speed of the wind at height h;

- ζ is the exponential coefficient based on ground surface roughness, typically between 0.08 and 0.52;

- dU/dH(h) is the expected wind gradient at height h.

In the 1862 American Civil War Battle of Iuka, an acoustic shadow, believed to have been enhanced by a northeast wind, kept two divisions of Union soldiers out of the battle, because they could not hear the sounds of battle only 10 km (six miles) downwind.

Tables

In the standard atmosphere:

- T0 is 273.15 K (= 0 °C = 32 °F), giving a theoretical value of 331.3 m/s (= 1086.9 ft/s = 1193 km/h = 741.1 mph = 644.0 kn). Values ranging from 331.3 to 331.6 m/s may be found in reference literature, however;

- T20 is 293.15 K (= 20 °C = 68 °F), giving a value of 343.2 m/s (= 1126.0 ft/s = 1236 km/h = 767.8 mph = 667.2 kn);

- T25 is 298.15 K (= 25 °C = 77 °F), giving a value of 346.1 m/s (= 1135.6 ft/s = 1246 km/h = 774.3 mph = 672.8 kn).

In fact, assuming an ideal gas, the speed of sound c depends on temperature and composition only, not on the pressure or density (since these change in lockstep for a given temperature and cancel out). Air is almost an ideal gas. The temperature of the air varies with altitude, giving the following variations in the speed of sound using the standard atmosphere—actual conditions may vary.

| Celsius temperature θ |

Speed of sound c |

Density of air ρ |

Characteristic specific acoustic impedance z0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 35 | 351.88 | 1.1455 | 403.2 |

| 30 | 349.02 | 1.1644 | 406.5 |

| 25 | 346.13 | 1.1839 | 409.4 |

| 20 | 343.21 | 1.2041 | 413.3 |

| 15 | 340.27 | 1.2250 | 416.9 |

| 10 | 337.31 | 1.2466 | 420.5 |

| 5 | 334.32 | 1.2690 | 424.3 |

| 0 | 331.30 | 1.2922 | 428.0 |

| −5 | 328.25 | 1.3163 | 432.1 |

| −10 | 325.18 | 1.3413 | 436.1 |

| −15 | 322.07 | 1.3673 | 440.3 |

| −20 | 318.94 | 1.3943 | 444.6 |

| −25 | 315.77 | 1.4224 | 449.1 |

Given normal atmospheric conditions, the temperature, and thus speed of sound, varies with altitude:

| Altitude | Temperature | m/s | km/h | mph | kn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sea level | 15 °C (59 °F) | 340 | 1,225 | 761 | 661 |

| 11,000 m to 20,000 m (cruising altitude of commercial jets, and first supersonic flight) |

−57 °C (−70 °F) | 295 | 1,062 | 660 | 573 |

| 29,000 m (flight of X-43A) | −48 °C (−53 °F) | 301 | 1,083 | 673 | 585 |

Effect of frequency and gas composition

General physical considerations

The medium in which a sound wave is travelling does not always respond adiabatically, and as a result, the speed of sound can vary with frequency.

The limitations of the concept of speed of sound due to extreme attenuation are also of concern. The attenuation which exists at sea level for high frequencies applies to successively lower frequencies as atmospheric pressure decreases, or as the mean free path increases. For this reason, the concept of speed of sound (except for frequencies approaching zero) progressively loses its range of applicability at high altitudes. The standard equations for the speed of sound apply with reasonable accuracy only to situations in which the wavelength of the sound wave is considerably longer than the mean free path of molecules in a gas.

The molecular composition of the gas contributes both as the mass (M) of the molecules, and their heat capacities, and so both have an influence on speed of sound. In general, at the same molecular mass, monatomic gases have slightly higher speed of sound (over 9% higher) because they have a higher γ (5/3 = 1.66...) than diatomics do (7/5 = 1.4). Thus, at the same molecular mass, the speed of sound of a monatomic gas goes up by a factor of

This gives the 9% difference, and would be a typical ratio for speeds of sound at room temperature in helium vs. deuterium, each with a molecular weight of 4. Sound travels faster in helium than deuterium because adiabatic compression heats helium more since the helium molecules can store heat energy from compression only in translation, but not rotation. Thus helium molecules (monatomic molecules) travel faster in a sound wave and transmit sound faster. (Sound travels at about 70% of the mean molecular speed in gases; the figure is 75% in monatomic gases and 68% in diatomic gases).

In this example we have assumed that temperature is low enough that heat capacities are not influenced by molecular vibration (see heat capacity). However, vibrational modes simply cause gammas which decrease toward 1, since vibration modes in a polyatomic gas give the gas additional ways to store heat which do not affect temperature, and thus do not affect molecular velocity and sound velocity. Thus, the effect of higher temperatures and vibrational heat capacity acts to increase the difference between the speed of sound in monatomic vs. polyatomic molecules, with the speed remaining greater in monatomics.

Practical application to air

By far, the most important factor influencing the speed of sound in air is temperature. The speed is proportional to the square root of the absolute temperature, giving an increase of about 0.6 m/s per degree Celsius. For this reason, the pitch of a musical wind instrument increases as its temperature increases.

The speed of sound is raised by humidity. The difference between 0% and 100% humidity is about 1.5 m/s at standard pressure and temperature, but the size of the humidity effect increases dramatically with temperature.

The dependence on frequency and pressure are normally insignificant in practical applications. In dry air, the speed of sound increases by about 0.1 m/s as the frequency rises from 10 Hz to 100 Hz. For audible frequencies above 100 Hz it is relatively constant. Standard values of the speed of sound are quoted in the limit of low frequencies, where the wavelength is large compared to the mean free path.

As shown above, the approximate value 1000/3 = 333.33... m/s is exact a little below 5 °C and is a good approximation for all "usual" outside temperatures (in temperate climates, at least), hence the usual rule of thumb to determine how far lightning has struck: count the seconds from the start of the lightning flash to the start of the corresponding roll of thunder and divide by 3: the result is the distance in kilometers to the nearest point of the lightning bolt. Or divide the number of seconds by 5 for an approximate distance in miles.

Mach number

Main article: Mach numberMach number, a useful quantity in aerodynamics, is the ratio of air speed to the local speed of sound. At altitude, for reasons explained, Mach number is a function of temperature. Aircraft flight instruments, however, operate using pressure differential to compute Mach number, not temperature. The assumption is that a particular pressure represents a particular altitude and, therefore, a standard temperature. Aircraft flight instruments need to operate this way because the stagnation pressure sensed by a Pitot tube is dependent on altitude as well as speed.

Experimental methods

A range of different methods exist for the measurement of the speed of sound in air.

The earliest reasonably accurate estimate of the speed of sound in air was made by William Derham and acknowledged by Isaac Newton. Derham had a telescope at the top of the tower of the Church of St Laurence in Upminster, England. On a calm day, a synchronized pocket watch would be given to an assistant who would fire a shotgun at a pre-determined time from a conspicuous point some miles away, across the countryside. This could be confirmed by telescope. He then measured the interval between seeing gunsmoke and arrival of the sound using a half-second pendulum. The distance from where the gun was fired was found by triangulation, and simple division (distance/time) provided velocity. Lastly, by making many observations, using a range of different distances, the inaccuracy of the half-second pendulum could be averaged out, giving his final estimate of the speed of sound. Modern stopwatches enable this method to be used today over distances as short as 200–400 metres, and not needing something as loud as a shotgun.

Single-shot timing methods

The simplest concept is the measurement made using two microphones and a fast recording device such as a digital storage scope. This method uses the following idea.

If a sound source and two microphones are arranged in a straight line, with the sound source at one end, then the following can be measured:

- The distance between the microphones (x), called microphone basis.

- The time of arrival between the signals (delay) reaching the different microphones (t).

Then v = x/t.

Other methods

In these methods, the time measurement has been replaced by a measurement of the inverse of time (frequency).

Kundt's tube is an example of an experiment which can be used to measure the speed of sound in a small volume. It has the advantage of being able to measure the speed of sound in any gas. This method uses a powder to make the nodes and antinodes visible to the human eye. This is an example of a compact experimental setup.

A tuning fork can be held near the mouth of a long pipe which is dipping into a barrel of water. In this system it is the case that the pipe can be brought to resonance if the length of the air column in the pipe is equal to (1 + 2n)λ/4 where n is an integer. As the antinodal point for the pipe at the open end is slightly outside the mouth of the pipe it is best to find two or more points of resonance and then measure half a wavelength between these.

Here it is the case that v = fλ.

High-precision measurements in air

The effect of impurities can be significant when making high-precision measurements. Chemical desiccants can be used to dry the air, but will, in turn, contaminate the sample. The air can be dried cryogenically, but this has the effect of removing the carbon dioxide as well; therefore many high-precision measurements are performed with air free of carbon dioxide rather than with natural air. A 2002 review found that a 1963 measurement by Smith and Harlow using a cylindrical resonator gave "the most probable value of the standard speed of sound to date." The experiment was done with air from which the carbon dioxide had been removed, but the result was then corrected for this effect so as to be applicable to real air. The experiments were done at 30 °C but corrected for temperature in order to report them at 0 °C. The result was 331.45 ± 0.01 m/s for dry air at STP, for frequencies from 93 Hz to 1,500 Hz.

Non-gaseous media

Speed of sound in solids

Three-dimensional solids

In a solid, there is a non-zero stiffness both for volumetric deformations and shear deformations. Hence, it is possible to generate sound waves with different velocities dependent on the deformation mode. Sound waves generating volumetric deformations (compression) and shear deformations (shearing) are called pressure waves (longitudinal waves) and shear waves (transverse waves), respectively. In earthquakes, the corresponding seismic waves are called P-waves (primary waves) and S-waves (secondary waves), respectively. The sound velocities of these two types of waves propagating in a homogeneous 3-dimensional solid are respectively given by where

- K is the bulk modulus of the elastic materials;

- G is the shear modulus of the elastic materials;

- E is the Young's modulus;

- ρ is the density;

- ν is Poisson's ratio.

The last quantity is not an independent one, as E = 3K(1 − 2ν). The speed of pressure waves depends both on the pressure and shear resistance properties of the material, while the speed of shear waves depends on the shear properties only.

Typically, pressure waves travel faster in materials than do shear waves, and in earthquakes this is the reason that the onset of an earthquake is often preceded by a quick upward-downward shock, before arrival of waves that produce a side-to-side motion. For example, for a typical steel alloy, K = 170 GPa, G = 80 GPa and p = 7700 kg/m, yielding a compressional speed csolid,p of 6,000 m/s. This is in reasonable agreement with csolid,p measured experimentally at 5,930 m/s for a (possibly different) type of steel. The shear speed csolid,s is estimated at 3,200 m/s using the same numbers.

Speed of sound in semiconductor solids can be very sensitive to the amount of electronic dopant in them.

One-dimensional solids

The speed of sound for pressure waves in stiff materials such as metals is sometimes given for "long rods" of the material in question, in which the speed is easier to measure. In rods where their diameter is shorter than a wavelength, the speed of pure pressure waves may be simplified and is given by: where E is Young's modulus. This is similar to the expression for shear waves, save that Young's modulus replaces the shear modulus. This speed of sound for pressure waves in long rods will always be slightly less than the same speed in homogeneous 3-dimensional solids, and the ratio of the speeds in the two different types of objects depends on Poisson's ratio for the material.

Speed of sound in liquids

In a fluid, the only non-zero stiffness is to volumetric deformation (a fluid does not sustain shear forces).

Hence the speed of sound in a fluid is given by where K is the bulk modulus of the fluid.

Water

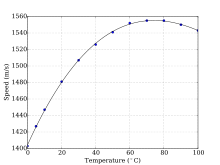

In fresh water, sound travels at about 1481 m/s at 20 °C (see the External Links section below for online calculators). Applications of underwater sound can be found in sonar, acoustic communication and acoustical oceanography.

Seawater

See also: Sound speed profile

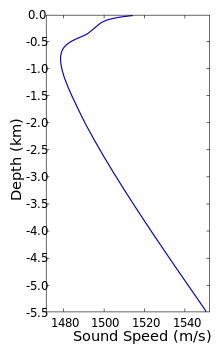

In salt water that is free of air bubbles or suspended sediment, sound travels at about 1500 m/s (1500.235 m/s at 1000 kilopascals, 10 °C and 3% salinity by one method). The speed of sound in seawater depends on pressure (hence depth), temperature (a change of 1 °C ~ 4 m/s), and salinity (a change of 1‰ ~ 1 m/s), and empirical equations have been derived to accurately calculate the speed of sound from these variables. Other factors affecting the speed of sound are minor. Since in most ocean regions temperature decreases with depth, the profile of the speed of sound with depth decreases to a minimum at a depth of several hundred metres. Below the minimum, sound speed increases again, as the effect of increasing pressure overcomes the effect of decreasing temperature (right). For more information see Dushaw et al.

An empirical equation for the speed of sound in sea water is provided by Mackenzie: where

- T is the temperature in degrees Celsius;

- S is the salinity in parts per thousand;

- z is the depth in metres.

The constants a1, a2, ..., a9 are with check value 1550.744 m/s for T = 25 °C, S = 35 parts per thousand, z = 1,000 m. This equation has a standard error of 0.070 m/s for salinity between 25 and 40 ppt. See for an online calculator.

(The Sound Speed vs. Depth graph does not correlate directly to the MacKenzie formula. This is due to the fact that the temperature and salinity varies at different depths. When T and S are held constant, the formula itself is always increasing with depth.)

Other equations for the speed of sound in sea water are accurate over a wide range of conditions, but are far more complicated, e.g., that by V. A. Del Grosso and the Chen-Millero-Li Equation.

Speed of sound in plasma

The speed of sound in a plasma for the common case that the electrons are hotter than the ions (but not too much hotter) is given by the formula (see here) where

- mi is the ion mass;

- μ is the ratio of ion mass to proton mass μ = mi/mp;

- Te is the electron temperature;

- Z is the charge state;

- k is Boltzmann constant;

- γ is the adiabatic index.

In contrast to a gas, the pressure and the density are provided by separate species: the pressure by the electrons and the density by the ions. The two are coupled through a fluctuating electric field.

Mars

The speed of sound on Mars varies as a function of frequency. Higher frequencies travel faster than lower frequencies. Higher frequency sound from lasers travels at 250 m/s (820 ft/s), while low frequency sound travels at 240 m/s (790 ft/s).

Gradients

Main article: Sound speed gradientWhen sound spreads out evenly in all directions in three dimensions, the intensity drops in proportion to the inverse square of the distance. However, in the ocean, there is a layer called the 'deep sound channel' or SOFAR channel which can confine sound waves at a particular depth.

In the SOFAR channel, the speed of sound is lower than that in the layers above and below. Just as light waves will refract towards a region of higher refractive index, sound waves will refract towards a region where their speed is reduced. The result is that sound gets confined in the layer, much the way light can be confined to a sheet of glass or optical fiber. Thus, the sound is confined in essentially two dimensions. In two dimensions the intensity drops in proportion to only the inverse of the distance. This allows waves to travel much further before being undetectably faint.

A similar effect occurs in the atmosphere. Project Mogul successfully used this effect to detect a nuclear explosion at a considerable distance.

See also

- Acoustoelastic effect

- Elastic wave

- Second sound

- Sonic boom

- Sound barrier

- Speeds of sound of the elements

- Underwater acoustics

- Vibrations

- Bell X-1

References

- "Speed of Sound Calculator". National Weather Service. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- C. R. Nave. "Speed of Sound". HyperPhysics. Department of Physics and Astronomy, Georgia State University. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- "The Speed of Sound". mathpages.com. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- Bannon, Mike; Kaputa, Frank (12 December 2014). "The Newton–Laplace Equation and Speed of Sound". Thermal Jackets. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Murdin, Paul (25 December 2008). Full Meridian of Glory: Perilous Adventures in the Competition to Measure the Earth. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 35–36. ISBN 9780387755342.

- Fox, Tony (2003). Essex Journal. Essex Arch & Hist Soc. pp. 12–16.

- "17.2 Speed of Sound | University Physics Volume 1". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- Dean, E. A. (August 1979). Atmospheric Effects on the Speed of Sound, Technical report of Defense Technical Information Center

- ^ Everest, F. (2001). The Master Handbook of Acoustics. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 262–263. ISBN 978-0-07-136097-5.

- ^ U.S. Standard Atmosphere, 1976, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1976.

- ^ Kinsler, L.E.; Frey, A.R.; Coppens, A.B.; Sanders, J.V. (2000). Fundamentals of Acoustics (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-84789-5.

- Uman, Martin (1984). Lightning. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-64575-9.

- Volland, Hans (1995). Handbook of Atmospheric Electrodynamics. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8493-8647-3.

- Singal, S. (2005). Noise Pollution and Control Strategy. Oxford: Alpha Science International. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-84265-237-4.

It may be seen that refraction effects occur only because there is a wind gradient and it is not due to the result of sound being convected along by the wind.

- Bies, David (2009). Engineering Noise Control, Theory and Practice. London: CRC Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-415-26713-7.

As wind speed generally increases with altitude, wind blowing towards the listener from the source will refract sound waves downwards, resulting in increased noise levels.

- Cornwall, Sir (1996). Grant as Military Commander. New York: Barnes & Noble. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-56619-913-1.

- Cozens, Peter (2006). The Darkest Days of the War: the Battles of Iuka and Corinth. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-5783-0.

- A B Wood, A Textbook of Sound (Bell, London, 1946)

- "Speed of Sound in Air". Phy.mtu.edu. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- Zuckerwar, Handbook of the speed of sound in real gases, p. 52

- J. Krautkrämer and H. Krautkrämer (1990), Ultrasonic testing of materials, 4th fully revised edition, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany, p. 497

- Slade, Tyler; Anand, Shashwat; Wood, Max; Male, James; Imasato, Kazuki; Cheikh, Dean; Al Malki, Muath; Agne, Matthias; Griffith, Kent; Bux, Sabah; Wolverton, Chris; Kanatzidis, Mercouri; Snyder, Jeff (2021). "Charge-carrier-mediated lattice softening contributes to high zT in thermoelectric semiconductors". Joule. 5 (5): 1168-1182. Bibcode:2021Joule...5.1168S. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2021.03.009. S2CID 233598665.

- "Speed of Sound in Water at Temperatures between 32–212 oF (0–100 oC) — imperial and SI units". The Engineering Toolbox.

- Wong, George S. K.; Zhu, Shi-ming (1995). "Speed of sound in seawater as a function of salinity, temperature, and pressure". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 97 (3): 1732. Bibcode:1995ASAJ...97.1732W. doi:10.1121/1.413048.

- APL-UW TR 9407 High-Frequency Ocean Environmental Acoustic Models Handbook, pp. I1-I2.

- Robinson, Stephen (22 September 2005). "Technical Guides – Speed of Sound in Sea-Water". National Physical Laboratory. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- "How Fast Does Sound Travel?". Discovery of Sound in the Sea. University of Rhode Island. Archived from the original on 20 May 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ^ Dushaw, Brian D.; Worcester, P. F.; Cornuelle, B. D.; Howe, B. M. (1993). "On Equations for the Speed of Sound in Seawater". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 93 (1): 255–275. Bibcode:1993ASAJ...93..255D. doi:10.1121/1.405660.

- Kenneth V., Mackenzie (1981). "Discussion of sea-water sound-speed determinations". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 70 (3): 801–806. Bibcode:1981ASAJ...70..801M. doi:10.1121/1.386919.

- Del Grosso, V. A. (1974). "New equation for speed of sound in natural waters (with comparisons to other equations)". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 56 (4): 1084–1091. Bibcode:1974ASAJ...56.1084D. doi:10.1121/1.1903388.

- Meinen, Christopher S.; Watts, D. Randolph (1997). "Further Evidence that the Sound-Speed Algorithm of Del Grosso Is More Accurate Than that of Chen and Millero". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 102 (4): 2058–2062. Bibcode:1997ASAJ..102.2058M. doi:10.1121/1.419655. S2CID 38144335.

- Maurice, S.; Chide, B.; Murdoch, N.; Lorenz, R. D.; Mimoun, D.; Wiens, R. C.; Stott, A.; Jacob, X.; Bertrand, T.; Montmessin, F.; Lanza, N. L.; Alvarez-Llamas, C.; Angel, S. M.; Aung, M.; Balaram, J. (1 April 2022). "In situ recording of Mars soundscape". Nature. 605 (7911): 653–658. Bibcode:2022Natur.605..653M. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04679-0. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 9132769. PMID 35364602.

External links

- Speed of Sound Calculator

- Calculation: Speed of Sound in Air and the Temperature

- Speed of sound: Temperature Matters, Not Air Pressure

- Properties of the U.S. Standard Atmosphere 1976

- The Speed of Sound

- How to Measure the Speed of Sound in a Laboratory

- Did Sound Once Travel at Light Speed?

- Acoustic Properties of Various Materials Including the Speed of Sound Archived 16 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Discovery of Sound in the Sea (uses of sound by humans and other animals)

where

where

is a coefficient of stiffness, the isentropic

is a coefficient of stiffness, the isentropic  is the

is the  , where

, where  is the pressure and the

is the pressure and the  through a pipe aligned with the

through a pipe aligned with the  axis and with a cross-sectional area of

axis and with a cross-sectional area of  . In time interval

. In time interval  it moves length

it moves length  . In

. In  must be the same at the two ends of the tube, therefore the

must be the same at the two ends of the tube, therefore the  is constant and

is constant and  . Per

. Per

Thus, from the Newton–Laplace equation above, the speed of sound in an ideal gas is given by

Thus, from the Newton–Laplace equation above, the speed of sound in an ideal gas is given by

where

where

) and arises because a classical sound wave induces an adiabatic compression, in which the heat of the compression does not have enough time to escape the pressure pulse, and thus contributes to the pressure induced by the compression;

) and arises because a classical sound wave induces an adiabatic compression, in which the heat of the compression does not have enough time to escape the pressure pulse, and thus contributes to the pressure induced by the compression; where

where

and using the ideal diatomic gas value of γ = 1.4000, we have

and using the ideal diatomic gas value of γ = 1.4000, we have

yields

yields

where

where

where

where

where E is

where E is  where K is the

where K is the  where

where

with check value 1550.744 m/s for T = 25 °C, S = 35 parts per thousand, z = 1,000 m. This equation has a standard error of 0.070 m/s for salinity between 25 and 40

with check value 1550.744 m/s for T = 25 °C, S = 35 parts per thousand, z = 1,000 m. This equation has a standard error of 0.070 m/s for salinity between 25 and 40  where

where