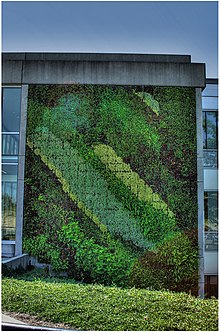

A green wall is a vertical built structure intentionally covered by vegetation. Green walls include a vertically applied growth medium such as soil, substitute substrate, or hydroculture felt; as well as an integrated hydration and fertigation delivery system. They are also referred to as living walls or vertical gardens, and widely associated with the delivery of many beneficial ecosystem services.

Green walls differ from the more established vertical greening typology of 'green facades' as they have the growth medium supported on the vertical face of the host wall (as described below), while green facades have the growth medium only at the base (either in a container or as a ground bed). Green facades typically support climbing plants that climb up the vertical face of the host wall, while green walls can accommodate a variety of plant species. Green walls may be implanted indoors or outdoors; as freestanding installations or attached to existing host walls; and applied in a variety of sizes.

Stanley Hart White, a Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Illinois from 1922 to 1959, patented a 'vegetation-Bearing Architectonic Structure and System' in 1938, though his invention did not progress beyond prototypes in his backyard in Urbana, Illinois. The popularising of green walls is often credited to Patrick Blanc, a French botanist specialised in tropical forest undergrowth. He worked with architect Adrien Fainsilber and engineer Peter Rice to implement the first successful large indoor green wall or Mur Vegetal in 1986 at the Cité des Sciences et de l'Industrie in Paris, and has since been involved with the design and implementation of a number of notable installations (e.g. Musée du quai Branly, collaborating with architect Jean Nouvel).

Green walls have seen a surge in popularity in recent times. An online database provided by greenroof.com for example had reported 80% of the 61 large-scale outdoor green walls listed as constructed after 2009, with 93% after 2007. Many notable green walls have been installed at institutional buildings and public places, with both outdoor and indoor installations gaining significant attention. As of 2015, the largest green wall is said to cover 2,700 square meters (29,063 square feet) and is located at the Los Cabos International Convention Centre designed by Mexican architect Fernando Romero.

Media types

Green walls are often constructed of modular panels that hold a growing medium and can be categorized according to the type of growth media used: loose media, mat media, and structural media.

Media-free

Media-free green walls are those that do not require soil substrates, fertilizers, or reticulated watering systems, and which utilize a method of selecting plant species which are best suited to the local climate. Media-free green walls often use a structural steel frame that is infilled with wire mesh, which is then attached to the façade of the structure, and plants are individually attached to this wire mesh. These frames are offset from the supporting structure to allow airflow between the green wall and the supporting structure, and this offset results in additional cooling to the adjoining building.

These media-free systems result in green walls which are considerably lighter than other methods, and also require significantly less maintenance, while the risk of liquid migration into adjoining structural walls is eliminated. The plant species which can be used in media-free systems varies depending on the location of the planned green wall. Xeric plants, such as Tillandsias, can be used because they absorb available atmospheric water and nutrients via trichome leaf cells, and their roots have developed to hold onto a support structure, unlike other plants which use their roots as a medium to absorb nutrients. The other benefit of Tillandsias within a media-free system is that these plants use a crassulacean acid metabolism to photosynthesize, and they have evolved to withstand long periods of heat and drought, and as a result, these plants grow slowly and require minimal maintenance.

Every three-to-five-years, any additional plant growth can be harvested to reduce weight, and these plant pups can be utilized for additional green walls. As long as suitable species are matched to the climate of the green wall's location, then potential plant losses across any three-to-five-year period is minor. As there is no watering system involved this method eliminates potential mold, algae and moss problems that can plague other systems. Because of the lack of media and water, these screens can also be installed horizontally, and the first of these screens ever installed was for a 2023 installation on the rooftop of the City of Melbourne's Council House 2 building.

Freestanding media

Freestanding media are portable living walls that are flexible for interior landscaping and are considered to have many biophilic design benefits. Zauben living walls are designed with hydroponic technology that conserves 75% more water than plants grown in soil, self-irrigates, and includes moisture sensors.

Loose media

Loose medium walls tend to be "soil-on-a-shelf" or "soil-in-a-bag" type systems. Loose medium systems have their soil packed into a shelf or bag and are then installed onto the wall. These systems require their media to be replaced at least once a year on exteriors and approximately every two years on interiors.

Loose soil systems are not well suited for areas with any seismic activity. Most importantly, because these systems can easily have their medium blown away by wind-driven rain or heavy winds, these should not be used in applications over 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in) high. There are some systems in Asia that have solved the loose media erosion problem by use of shielding systems to hold the media within the green wall system even when soil liquefaction occurs under seismic load. In these systems, the plants can still up-root themselves in the liquified soil under seismic load, and therefore it is required that the plants be secured to the system to prevent them from falling from the wall.

Loose-soil systems without physical media erosion systems are best suited for the home gardener where occasional replanting is desired from season to season or year to year. Loose-soil systems with physical media erosion systems are well suited for all green wall applications.

Mat media

Mat type systems tend to be either coir fiber or felt mats. Mat media are quite thin, even in multiple layers, and as such cannot support vibrant root systems of mature plants for more than three to five years before the roots overtake the mat and water is not able to adequately wick through the mats.

The method of reparation of these systems is to replace large sections of the system at a time by cutting the mat out of the wall and replacing it with new mat. This process compromises the root structures of the neighboring plants on the wall and often kills many surrounding plants in the reparation process.

These systems are best used on the interior of a building and are a good choice in areas with low seismic activity and small plants that will not grow to a weight that could rip the mat apart under their own weight over time.

Mat systems are particularly water inefficient and often require constant irrigation due to the thin nature of the medium and its inability to hold water and provide a buffer for the plant roots. This inefficiency often requires that these systems have a water re-circulation system put into place at an additional cost. Mat media are better suited for small installations no more than eight feet in height where repairs are easily completed.

Sheet media

Semi-open cell polyurethane sheet media utilising an egg crate pattern has successfully been used in recent years for both outdoor roof gardens and vertical walls. The water holding capacity of these engineered polyurethanes vastly exceeds that of coir and felt based systems. Polyurethanes do not biodegrade, and hence stay viable as an active substrate for 20+ years. Vertical wall systems utilising polyurethane sheeting typically employ a sandwich construction where a water proof membrane is applied to the back, the polyurethane sheeting (typically two sheets with irrigation lines in between) is laid and then a mesh or anchor braces/bars secure the assembly to the wall. Pockets are cut into the face of the first urethane sheet into which plants are inserted. Soil is typically removed from the roots of any plants prior to insertion into the urethane mattress substrate. A flaked or chopped noodle version of the same polyurethane material can also be added to existing structural media mixes to boost water retention.

Structural media

The Green Wall in Sutton High Street, Sutton, Greater London

The Green Wall in Sutton High Street, Sutton, Greater London

Structural media are growth medium "blocks" that are not loose, nor mats, but which incorporate the best features of both into a block that can be manufactured into various sizes, shapes and thicknesses. These media have the advantage that they do not break down for 10 to 15 years, can be made to have a higher or lower water holding capacity depending on the plant selection for the wall, can have their pH and EC's customized to suit the plants, and are easily handled for maintenance and replacement.

There is also some discussion involving "active" living walls. An active living wall actively pulls or forces air through the plants le quality to the point that the installation of other air quality filtration systems can be removed to provide a cost-savings. Therefore, the added cost of design, planning and implementation of an active living wall is still in question. With further research and UL standards to support the air quality data from the living wall, building code may one day allow for our buildings to have their air filtered by plants.

The area of air quality and plants is continuing to be researched. Early studies in this area include NASA studies performed in the 1970s and 1980s by B. C. Wolverton. There was also a study performed at the University of Guelph by Alan Darlington. Other research has shown the effect the plants have on the health of office workers.

Function

Green walls are found most often in urban environments where the plants reduce overall temperatures of the building. "The primary cause of heat build-up in cities is insolation, the absorption of solar radiation by roads and buildings in the city and the storage of this heat in the building material and its subsequent re-radiation. Plant surfaces however, as a result of transpiration, do not rise more than 4–5 °C above the ambient and are sometimes cooler."

Living walls could function as urban agriculture, urban gardening, or provide aesthetic enhancement as art installations. They are particularly suitable for cities, as they allow good use of available vertical surface areas. They are also suitable in arid areas, as the circulating water on a vertical wall is less likely to evaporate than in horizontal gardens. It is sometimes built indoors to help alleviate sick building syndrome. Living walls are also acknowledged for remediation of poor air quality, in both internal and external environments.

Water management

Living walls may also be a means for water reuse and management. The plants purify slightly polluted water (such as greywater) by absorbing the dissolved nutrients. Bacteria mineralize the organic components to make them available to the plants. A study is underway at the Bertschi School in Seattle, Washington, using a GSky Pro Wall system, however, no publicly available data on this is available at this time.

Phytoremediation and air quality improvement Green walls provide an additional layer of insulation that can protect buildings from heavy rainwater which leads to management of heavy storm water and provides thermal mass. They also help reduce the temperature of a building because vegetation absorbs large amounts of solar radiation. This can reduce energy demands and cleanse the air from VOC’s (Volatile Organic Compounds) released by paints, furniture, and adhesives. Off-gassing from VOCs can cause headaches, eye irritation, and airway irritation and internal air pollution. Green walls can also purify the air from mould growth in building interiors that can cause asthma and allergies.

Indoor green walls can have a therapeutic effect from exposure to vegetation. The aesthetic feel and visual appearance of green walls are other examples of the benefits - but also affects the indoor climate with reduced CO2 level, noise level and air pollution abatement. However, to have the optimal effect on the indoor climate it is important that the plants in the green wall have the best conditions for growth, both when talking about watering, fertilizing and the right amount of light. To have the best result on all of the aforementioned, some green wall systems has special and patented technologies that is developed to the benefit of the plants.

Thomas Pugh, a biogeochemist at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in Germany, created a computer model of a green wall with a broad selection of vegetation. The study showed results of the green wall absorbing nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter. In street canyons where polluted air is trapped, green walls can absorb the polluted air and purify the streets.

Acoustic performance

Another significant function in urban areas is acoustic moderation. Plants attenuate noise by absorbing, diffracting, reflecting, and scattering sound. Vegetated installations have as a result been widely used as means to improve outdoor and indoor sound environments.

Biodiversity enhancement

Traditional green facades are best characterised as ‘Xerothermophilous’ habitats comparable to cliffs, while continuous felt and modular substrate-filled living wall types are best characterised as damp and cool habitats comparable to vegetated waterfalls. Systems with increased substrate depth are typically found to offer the highest diversity and abundance of species. Biodiversity at indoor applications in contrast is likely to be significantly limited owing to the restricted ecosystems created, with introductions most likely at planting or replanting stages.

Plants

List of plants best suited for Media Free gardens

List of herbs best suited for green facades

- Basil

- Bay laurel

- Caraway

- Chamomile

- Chives

- Coriander

- Curry plant

- Dill

- Lavender

- Lemon balm

- Lemongrass

- Marjoram

- Mint

- Oregano

- Parsley

- Rosemary

- Sage

- Sorrel

- Tarragon

- Thyme

Edible plants best suited for green facades

- Chard

- Cherry tomatoes

- Dwarf cabbages

- Lettuce

- Radishes

- Rocket

- Silverbeet

- Small chili peppers

- Spinach

- Strawberries

- Watercress

Plants for sun

- Achillea

- Acorus

- Armeria maritima

- Bergenia

- Bidens

- Calamintha nepeta

- Carex

- Convolvulus cneorum

- Erica

- Geranium

- Lavender

- Liriope

- Pansy

- Rosemary

- Sedum

- Solidago

- Thyme

- Westringia

Plants for shade

- Adiantum

- Asplenium

- Begonia

- Bergenia

- Chlorophytum comosum

- Erica

- Euphorbia

- Heuchera

- Polystichum

- Snowdrop

Sources

- Clapp, L., & Klotz, H. (2018). Vertical gardens. London; Sydney; Auckland: New Holland.

- Coronado, S. (2015). Grow a living wall - create vertical gardens with purpose: Pollinators - he. Cool Springs Press.

- Hyatt, B. (2017, June 29). The ins and outs of green wall installation and maintenance. Retrieved March 2, 2019, from https://www.totallandscapecare.com/landscaping/green-wall-maintenance/

- Manso, Maria; Castro-Gomes, João (January 2015). "Green wall systems: A review of their characteristics". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 41: 863–871. Bibcode:2015RSERv..41..863M. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.203. S2CID 110322582.

- Gunawardena, K., & Steemers, K. (2019). Living walls in indoor environments. Building and Environment, 148 (January 2019), 478–487. Living walls in indoor environments

- Pictures: Green Walls May Cut Pollution in Cities. (2016, May 17). Retrieved from https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/03/pictures/130325-green-walls-environment-cities-science-pollution/

- Reggev, K. (2018, January 18). Living Green Walls 101: Their Benefits and How They're Made. Retrieved March 2, 2019, from https://www.dwell.com/article/living-green-walls-101-their-benefits-and-how-theyre-made-350955f3

- Thomas A. M. Pugh; A. Robert MacKenzie; J. Duncan Whyatt; C. Nicholas Hewitt (2012). "The effectiveness of green infrastructure for improvement of air quality in urban street canyons" (PDF). Environmental Science & Technology. 46 (14): 7692–7699. Bibcode:2012EnST...46.7692P. doi:10.1021/es300826w. PMID 22663154.

- Visone, M. (2019). Down to the Vertical Gardens. Compasses, 32, 33-40. Down to the Vertical Gardens

See also

- Building-integrated agriculture

- CityTrees

- Folkewall

- Greening

- Green building

- Great Green Wall (Africa)

- Great Green Wall (China)

- Green roof

- The Hanging Gardens of Babylon

- Hügelkultur

- Roof garden

- Vertical farming

- Vertical forest

References

- ^ Medl, Alexandra; Stangl, Rosemarie; Florineth, Florin (2017-11-15). "Vertical greening systems – A review on recent technologies and research advancement". Building and Environment. 125: 227–239. Bibcode:2017BuEnv.125..227M. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2017.08.054. ISSN 0360-1323.

- ^ Gunawardena, Kanchane; Steemers, Koen (2019-01-15). "Living walls in indoor environments". Building and Environment. 148: 478–487. Bibcode:2019BuEnv.148..478G. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.11.014. ISSN 0360-1323. S2CID 116429180.

- "Vertical gardens in the city: how to green up your apartment building creatively".

- Hindle, Richard L. "Reconstructing the 'Vegetation-Bearing Architectonic Structure and System (1938)'". Graham Foundation. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- Hindle, Richard L. (June 2012). "A vertical garden: origins of the Vegetation-Bearing Architectonic Structure and System (1938)". Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes. 32 (2): 99–110. doi:10.1080/14601176.2011.653535. S2CID 56350350. Archived from the original on 2019-06-26. Retrieved 2019-06-26.

- "Vertical gardens a green solution for urban setting". The Times of India. Feb 14, 2013. Archived from the original on May 6, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- "Welcome to Vertical Garden Patrick Blanc – Vertical Garden Patrick Blanc". www.verticalgardenpatrickblanc.com. Archived from the original on 2017-01-06. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- "The International Greenroof & Greenwall Projects Database!". greenroofs.com. Greenroofs.com, LLC. Archived from the original on 18 October 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

select 'green wall' as type and 'living wall' under 'greenroof type'

- "Upwards trend". www.airport-world.com. Airport World. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

An increasing number of airports are investing in vertical gardens and living walls to create a unique setting

- For largest wall as of 2012, see Eric Martin; Nacha Cattan (Jun 20, 2012). "Calderon Fetes G-20 as Sun Sets on Mexico Ruling Party". bloomberg.com. Bloomberg LP. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- For size of wall, see "Los Cabos International Convention Center (ICC)". greenroofs.com. Greenroofs.com, LLC. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "Council House 2 horizontal Tillandsia screen". Lloyd Godman. April 2023. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- "Off Grid Living". 2019-10-12. Retrieved 2022-09-02.

- "Purdue Solar Decathlon". www.purdue.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-10-18. Retrieved 2017-06-26.

- "Wolverton Environmental Services". www.wolvertonenvironmental.com. Archived from the original on 2008-03-10.

- Darlington, A; Chan, M; Malloch, D; Pilger, C; Dixon, MA (March 2000). "The biofiltration of indoor air: implications for air quality". Indoor Air. 10 (1): 39–46. Bibcode:2000InAir..10...39D. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0668.2000.010001039.x. PMID 10842459.

- Fjeld, Tove; Veiersted, Bo; Sandvik, Leiv; Riise, Geir; Levy, Finn (1998). "The Effect of Indoor Foliage Plants on Health and Discomfort Symptoms among Office Workers". Indoor and Built Environment. 7 (4): 204–209. doi:10.1177/1420326x9800700404. S2CID 111319315.

- Ong, Boon Lay (May 2003). "Green plot ratio: an ecological measure for architecture and urban planning". Landscape and Urban Planning. 63 (4): 197–211. Bibcode:2003LUrbP..63..197O. doi:10.1016/S0169-2046(02)00191-3.

- Wolverton, B. C.; Johnson, Anne; Bounds, Keith (15 September 1989). "Interior Landscape Plants for Indoor Air Pollution Abatement" (PDF).

- "Living green walls from Natural Greenwalls for offices and professionals".

- Madre, Frédéric; Clergeau, Philippe; Machon, Nathalie; Vergnes, Alan (2015). "Building biodiversity: Vegetated façades as habitats for spider and beetle assemblages". Global Ecology and Conservation. 3: 222–233. Bibcode:2015GEcoC...3..222M. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2014.11.016. ISSN 2351-9894.

External links

- Green Infrastructure Resource Guide

- Air pollution-eating moss cleans hotspots in Europe

- City Tree helping to deliver cleaner air for Putney