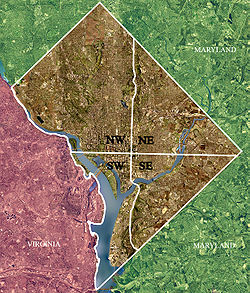

Southwest (SW or S.W.) is the southwestern quadrant of Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States, and is located south of the National Mall and west of South Capitol Street. It is the smallest quadrant of the city, and contains a small number of named neighborhoods and districts, including Bellevue, Southwest Federal Center, the Southwest Waterfront, Buzzard Point, and the military installation known as Joint Base Anacostia–Bolling.

Geography

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Southwest has the following districts and neighborhoods:

- the Southwest Federal Center, also called the Southwest Employment District, is the area between the National Mall and the Southeast/Southwest Freeway (Interstate 395).

- Southwest Federal Center contains the Smithsonian Institution museums along the south side of the Mall—including the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, the National Museum of African Art, the Freer Gallery of Art, the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, the National Air and Space Museum, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and the National Museum of the American Indian—as well as the United States Botanical Gardens, L'Enfant Plaza and a large concentration of federal executive branch office buildings for departments as well the House office buildings;

- Southwest Federal Center is in Ward 2.

- the Southwest Waterfront, also called Near Southwest, is between I-395 and Fort Lesley J. McNair.

- Southwest Waterfront is a primarily residential neighborhood. It also is home to several Washington DC marinas, including the Washington Marina, The Capitol Yacht Club, the Gangplank Marina, and the James Creek Marina.

- It is also home to the Maine Avenue Fish Market, Arena Stage, the Washington Marina, Fort McNair, and Hains Point; East and West Potomac Park, a conjunction of two national parks between I-395 and the National Mall that contain the Tidal Basin, the Jefferson Memorial, and the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial (West Potomac Park continues into Northwest and includes the Lincoln Memorial and World War II Memorial, both of which straddle the Southwest/Northwest boundary);

- Southwest Waterfront is in Ward 6, except for the unpopulated East and West Potomac Parks, which are in Ward 2.

- Buzzard Point, a largely under-developed industrial area between South Capitol Street and Fort McNair.

- Buzzard Point contains Audi Field, home of local MLS team D.C. United, winner of 4 MLS Cups. It is also home to the Matthew A. Henson Earth Conservation Center. Prior to 2013, Buzzard Point was the home of the U.S. Coast Guard, which was headquartered in a building at the confluence of the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers. The headquarters then moved to the former St. Elizabeths Hospital campus in Southeast Washington near Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling to a building renamed the Douglas A. Munro Coast Guard Headquarters Building.

- the area of Southwest that is south and east of the Anacostia River contains Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling together with the Naval Research Laboratory and the Blue Plains Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant, Job Corps Center, and Fire Department Training Center.

- Bolling is in Ward 8.

- the Bellevue neighborhood occupies all of the Southwest land between South Capitol Street (to the east) and the Anacostia and Potomac rivers (to the west and north). Included is the small Hadley Hospital.

- Bellevue is in Ward 8.

Transportation

The Blue, Orange, and Silver lines of the Washington Metro have the following stations in the Southwest Federal Center: Smithsonian, L'Enfant Plaza, and Federal Center SW.

The Green line has a stop in the Southwest Federal Center at L'Enfant Plaza and in the Southwest Waterfront at Waterfront; additionally, the Navy Yard – Ballpark stop is one block outside the eastern boundary of the Southwest Waterfront neighborhood.

History

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Before 1950

Southwest is part of Pierre L'Enfant's original city plans and includes some of the oldest buildings in the city, including the Wheat Row block of townhouses, built in 1793, and Fort McNair, which was established in 1791 as "the U.S. Arsenal at Greenleaf Point."

Before 1847, much of the Virginia portion of the District of Columbia, including the town of Alexandria, was included in Southwest.

After the Civil War, the Southwest Waterfront became a neighborhood for the poorer classes of Washingtonians. The neighborhood was divided in half by Fourth Street SW, then known as 41⁄2 Street; Scotch, Irish, German, and eastern European immigrants lived west of 41⁄2 Street, while freed blacks lived to the east. Each half was centered on religious establishments: St. Dominic's Catholic Church and Talmud Torah Congregation on the west, and Friendship Baptist Church on the east. (Also, each half of the neighborhood was the childhood home of a future American musical star — the first home of Al Jolson, whose father was the cantor of Talmud Torah Congregation, after his family emigrated from what is now Lithuania was on 41⁄2 Street, and Marvin Gaye was born in a tenement on First Street.)

Waterfront developed into a quite contradictory area: it had a thriving commercial district with grocery stores, shops, a movie theater, as well as a few large and elaborate houses (mostly owned by wealthy blacks). However, most of the neighborhood was a very poor shantytown of tenements, shacks, and even tents. These places, some of them in the shadow of the Capitol Building, were frequent subjects of photographs highlighting the stark contrast.

1950s rebuilding

In the 1950s, city planners working with the U.S. Congress decided that Southwest should undergo a significant urban renewal — in this case, meaning that the city would declare eminent domain over all land south of the National Mall and north of the Anacostia River (except Fort McNair); evict virtually all of its residents and businesses; destroy all streets, buildings, and landscapes; and start again from scratch. The seizure of the entire area, including well maintained properties, was upheld by the United States Supreme Court in Berman v. Parker. Justice William Douglas emphasized the squalor and segregation the area suffered, noting that the area was 98% black while 58% of dwellings had outside toilets.

Only a few buildings were left intact, notably the Maine Avenue fish market, the Wheat Row townhouses, the Thomas Law House, and the St. Dominic's and Friendship churches. The Southeast/Southwest Freeway was constructed where F Street, SW, had once been.

The rebuilt Southwest featured a large concentration of office and residential buildings in the brutalist style that was then popular. It was during this time that most of the Southwest Federal Center was built. The heart of the urban renewal of the Southwest Waterfront was Waterside Mall, a small shopping center and office complex, which housed satellite offices for the United States Environmental Protection Agency. The Arena Stage was built a block west of the Mall, and a number of hotels and restaurants were built on the riverfront to attract tourists. Southeastern University, a very small college that had been chartered in 1937, also established itself as an important institution in the area. Following a proposal by Chloethiel Woodard Smith and Louis Justement, renewal in Southwest marked one of the last great efforts of the late Modernist movement. Architect I. M. Pei developed the initial urban renewal plan and was responsible for the design of multiple buildings, including those comprising L’Enfant Plaza and two clusters of apartment buildings located on the north side of M St. SW, initially called Town Center Plaza). Various firms oversaw individual projects and many of these represent significant architectural contributions. Modernist Charles M. Goodman designed the River Park Mutual Homes complex. Likewise, Harry Weese designed the new building for Arena Stage and Marcel Breuer the Robert C. Weaver Federal Building, located at 451 Seventh Street, SW, to house the newly established U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the Hubert H. Humphrey Federal Building. The Tiber Island complex, which was designed as a replica of the adjacent Carollsburg Condominium and Carrollsburg Square, were designed by Keyes, Lethbridge & Condon, and won an American Institute of Architects award in 1966.

However, urban renewal did not fully succeed in Southwest for many of the reasons that plagued other Modernist renewal efforts. Areas of the neighborhood remained run-down, low-income, and somewhat dangerous. This situation intensified in the 1980s and the 1990s, when Washington had among the lowest per capita incomes and highest crime rates in the nation. The Southwest urban renewal has been called "a case study of everything urban renewal got wrong about cities and people."

Recent redevelopment

While many of the residential neighborhoods of Southwest remained both highly mixed-race and mixed-income, around 2003, the wave of new development occurring throughout D.C. reached Southwest including a number of apartment building renovations and condominium conversions. Nationals Park stadium, located on the east side of South Capitol Street and thus in Southeast, opened for the Washington Nationals Major League Baseball team in 2008, construction having cost more than $611 million. As part of the Capitol Riverfront revitalization efforts, high rise office buildings and condominiums have been constructed. Developers have created a waterfront greenspace The Yards, and a waterfront bike trail is planned. Public Housing projects continue to occupy the area between the Waterfront metro and the Nationals Park stadium.

On April 16, 2010, the new Waterfront Safeway (including a sushi bar). 38°52′52″N 77°00′58″W / 38.881228°N 77.01622°W / 38.881228; -77.01622 Along Water Street, "The Wharf" includes restaurants, shopping, theaters, public piers, hotels, and high-rise housing; the first phase opened in October 2017 (see Redevelopment of Southwest Waterfront) with phase two slated to deliver in early 2022.

L'Enfant Plaza has also undergone a facelift, with new retail and hotels, as well as office renovations having been completed in the late 2010s. In April 2017, the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) approved plans for a staircase and ramp that will travel through a grassy slope in Benjamin Banneker Park to connect L'Enfant Plaza to the Southwest Waterfront and to add lighting and trees to the area. The NCPC and the National Park Service intended the project to be an interim improvement that could be in place for ten years while the area awaits redevelopment. Hoffman-Madison Waterfront (the developer of "The Wharf") and the District of Columbia government agreed to invest $4 million in the project in an effort to improve neighborhood connectivity in the area. Construction began on the project in September 2017.

Notable residents

Notable past and present residents of Southwest Washington, D.C. include:

- John Conyers, former U.S. Representative

- Marvin Gaye, Motown singer and songwriter

- Denyce Graves, opera singer

- Dennis Hastert, former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives

- Hubert Humphrey, former U.S. vice president and U.S. Senator

- Kay Bailey Hutchison, former U.S. Senator and U.S. Permanent Representative to NATO

- Al Jolson, former singer and actor

- Carolyn Cheeks Kilpatrick, U.S. Representative

- Thurgood Marshall, former U.S. Supreme Court associate justice

- Lewis F. Powell Jr., former U.S. Supreme Court associate justice

- Charles H. Ramsey, former Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. police commissioner

- Paul Simon, former U.S. Senator and U.S. Representative

- David Souter, former U.S. Supreme Court associate justice

- Strom Thurmond, former U.S. Senator

See also

References

- Olitzky, Kerry. The American Synagogue: A Historical Dictionary and Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 92.

- (1) "Washington, D.C.: A Challenge to Jim Crow in the Nation's Capital". Separate Is Not Equal - Brown v. Board of Education. Smithsonian Institution: National Museum of American History: Behring Center. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

(2) Williams, Paul K. (2005). Chapter 5: The Southwest Neighborhood: 1870-1950. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 83. ISBN 0738542199. LCCN 2005935864. OCLC 69989394. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018 – via Google Books.{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Berman v. Parker, 384 U.S. 26 (1954). Archived April 19, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- "U.S. Army Corps of Engineers" (PDF). usace.army.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2008. Retrieved March 23, 2008.

- "Pei Cobb Freed and Partners". pcf-p.com. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved March 23, 2008.

- "Robert C. Weaver Federal Building (HUD), Washington, DC". gsa.gov. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved April 11, 2007.

- "AIA Honor Awards 1960–1969". aia.org. Archived from the original on April 12, 2008. Retrieved March 23, 2008.

- Do posh waterfronts make a city world-class? D.C. is betting hundreds of millions on it., The Washington Post, June 26, 2018

- "Waterfront Safeway Open for Business". NBC Washington. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- Wharf, The. "Construction Begins On Second Phase Of The Wharf". www.prnewswire.com. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- (1) "About District Wharf". District Wharf. PN Hoffman; Madison Marquette. 2018. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

(2) Freed, Benjamin (March 19, 2014). "The Wharf Breaks Ground in DC's Southwest Waterfront: The first phase of the $2 billion project will include hundreds of new residences, shops and restaurants, and a massive concert venue". Washingtonian. Washingtonian Media Inc. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

(3) Sadon, Rachel (October 2, 2017). "The Wharf's Grand Opening Involves Four Days Of Events, And Kevin Bacon Is Involved". DCist. Gothamist, LLC. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

(4) Iannelli, Nick (October 12, 2017). "The Wharf opens along DC's Southwest waterfront". WTOP. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018. - "Overview". L'Enfant Plaza. Archived from the original on March 7, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- (1) "Environmental Assessment: Benjamin Banneker Park Connection" (PDF). National Mall and Memorial Parks. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service. March 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 16, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

(2) Koster, Julia; Staudigl, Stephen (April 6, 2017). "NCPC Approves Banneker Park Pedestrian and Cyclist Access Improvements" (PDF). Media Release. Washington, D.C.: National Capital Planning Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 13, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

(3) "Banneker Park Pedestrian Access Improvements" (PDF). Executive Director's Recommendation: Commission Meeting: April 6, 2017 (NCPC File No. 7551). Washington, D.C.: National Capital Planning Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 13, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

(4) Voigt, Eliza. "Benjamin Banneker Park Pedestrian Access Improvements". National Mall and Memorial Parks. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 13, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017. - "Construction on Benjamin Banneker Park Pedestrian and Bike Access Project begins ahead of The Wharf's October 12 Launch". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development: Government of the District of Columbia (DC.gov). September 8, 2017. Archived from the original on November 13, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- "Southwest Neighborhood - Fun Facts". Southwest Neighborhood Assembly. November 25, 1966. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- "With a Good Cough". Time. November 25, 1966. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- "Kay Bailey Hutchison Sells Her Southwest digs". UrbanTurf. November 2, 2012. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

External links

- Southwest D.C. Community website

- Southwest D.C. real estate website

- Southwest Heritage Trail (pamphlet)

| Quadrants of Washington, D.C. | |

|---|---|