| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "William Morris wallpaper designs" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The British literary figure and designer William Morris (1834-1896), a founder of the British Arts and Crafts Movement, was especially known for his wallpaper designs. These were created for the firm he founded with his partners in 1861, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Company, and later for Morris and Company. He created fifty different block-printed wallpapers, all with intricate, stylised patterns based on nature, particularly upon the native flowers and plants of Britain. His wallpapers and textile designs had a major effect on British interior designs, and then upon the subsequent Art Nouveau movement in Europe and the United States.

The 1860s - experiments and early designs

His partners in the company were members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group of painters who rejected the art and design of the Victorian era, and sought to revive earlier themes and techniques of art and craftsmanship. The first wallpaper pattern he designed for his company was the Trellis wallpaper in 1864. It was inspired by the roses he grew on the trellis at his residence, the Red House. However, two years passed between the time he designed the paper and the time he was able to print it to his satisfaction. His primary objective was to make the wallpaper by hand, with transparent oil colours on zinc plates. However, when he could not make this work to his satisfaction, he gave the task to an established wallpaper firm, Jeffrey and company, which printed it with wood blocks and distemper colours. Since Morris was a perfectionist, this also was a long process. He was dissatisfied by the early versions, and at one point threw away the entire set of printing blocks. The final versions were printed in different colours. For the bedroom of his own residence Kelmscott House, which he decorated in 1879, he used the trellis design with a blue background.

-

Design for Trellis wallpaper (1862)

Design for Trellis wallpaper (1862)

-

Finished Trellis wallpaper printed in 1864

Finished Trellis wallpaper printed in 1864

-

Daisy Design (1864)

Daisy Design (1864)

-

Fruit or pomegranate (1866) (Metropolitan Museum)

Fruit or pomegranate (1866) (Metropolitan Museum)

In the following years, he made two more floral designs, Daisy (1864), and Fruit/Pomegranate (1866). All three were created in a variety of different colours. The multitude of colours used and the careful work involved made these wallpapers particularly expensive. Since he was running a business, he had to adapt to the wishes of the market. At the end of the 1860s, in order to bring in more orders, he created an entirely different group of four papers based on a new design, called the Indian. Since they had only two colours, they were less expensive. In 1868, though he disliked the Victorian idea of using several different designs of wallpaper in the same room, intended especially for the ceilings of rooms.

The early 1870s - mastery of technique

In the 1870s, through practice and continual refinement, he achieved a mastery of the technique and a more sophisticated and subtle style, with a finer balance between color, variety, and structure. He wrote later in his 1881 lecture, Some hints on pattern designing, of the necessity "to mask the construction of our pattern enough to prevent people from counting the repeats of our pattern, while we manage to lull their curiosity to trace it out." The purpose of a good pattern, he wrote, "was a look of satisfying mystery, which is essential in all patterned goods, and which must be done by the designer." He added that "colour above all should be modest," since the wallpaper was part of the household, meant to be lived with and seen only in passing, not meant to attract attention to itself.

During this period he created some of this most famous designs, creating an illusion of three dimension, with lavish flowers interwoven with a complex and lush background. His designs in this period included 'Larkspur' (1872), 'Jasmine' (1872), 'Willow' (1874), 'Marigold' (1875), 'Wreath' and 'Chrysanthemum' (both 1876). The Morris wallpapers were expensive to produce. A typical Morris wallpaper in the 1870s required as much as four weeks to manufacture, using thirty different printing blocks and fifteen separate colours.

The wallpapers of Morris were regarded as strange and excessive for most wealthy Victorians, who preferred the more geometric and traditional French styles. The early clients of Morris' wallpapers were mostly his avant-garde artist friends. His early designs were purchased by his close friend painter Edward Burne-Jones, and Punch cartoonist Edward Linley Sambourne. He also had as few avant-garde aristocratic clients, including the Earl and Countess of Carlisle, who used the 'Bird and Anemone' and two sunflower designs in their home at Castle Howard in Yorkshire.

-

Larkspur design (1874) (Cooper-Hewitt Museum)

Larkspur design (1874) (Cooper-Hewitt Museum)

-

Powdered wallpaper (1874)

Powdered wallpaper (1874)

-

Acanthus design (1875) (Victoria and Albert Museum)

Acanthus design (1875) (Victoria and Albert Museum)

-

Marigold design (1875)(Metropolitan Museum)

Marigold design (1875)(Metropolitan Museum)

-

Pimpernel design at Two Temple Place, London (1876)

Pimpernel design at Two Temple Place, London (1876)

Late 1870s to the 1890s - Royal attention and final wallpapers

The period between 1876 and 1882 was the most productive for Morris; he created sixteen different wallpaper designs. In his wallpapers of this period, he reverted to more naturalistic themes, somewhat less three-dimensional than his earlier work, but with an exceptional harmony and rhythm, as in his designs Poppy (1885) and Acorn.

In the 1880s, his work finally received royal attention: In 1880 he was asked to redecorate rooms St. James's Palace in London. He created a particularly complex design, named 'St. James's', which used sixty-eight separate printing blocks to make a section of two wallpaper widths, with a height 127 centimeters. In 1887 Queen Victoria again commissioned Morris & Company, this time to another special design for wallpaper at Balmoral Castle, based on the 'VRI' initials of the Queen.

During this time, however, Morris was devoting more and more of his time to literary and political work. He also became increasingly involved in other media, especially textile and tapestry weaving. He relocated the workshops of his company to Merton Abbey in the 1880s to focus on these. He also began to create wallpapers with a single color, such as Acorn and Sunflower, which were much simpler and much less expensive to produce. Among his final wallpapers was the Red Poppy design.

-

Pink and Poppy Wallpaper (1881)

Pink and Poppy Wallpaper (1881)

-

Grafton wallpaper (1883)

Grafton wallpaper (1883)

-

Wild Tulip (1884) (Metropolitan Museum)

Wild Tulip (1884) (Metropolitan Museum)

-

Pink and Rose (1890) (Metropolitan Museum)

Pink and Rose (1890) (Metropolitan Museum)

-

Blackthorn (1892) (Metropolitan Museum)

Blackthorn (1892) (Metropolitan Museum)

-

Willow Bough (1887) (Metropolitan Museum)

Willow Bough (1887) (Metropolitan Museum)

-

Morris wallpaper in Wightwick Manor (c. 1887–93)

Morris wallpaper in Wightwick Manor (c. 1887–93)

Technique

Between 1864 and 1867, for his early wallpapers such as the Trellis, Fruit/Pomegranate, he experimented with printing them with blocks of zinc but decided that this was too complex and took too long. He turned to a commercial company, Barrett of Bethnal Green, which made the first blocks for him in the traditional way from pearwood. For the printing, he turned to the firm of M.M. Jeffrey & Company of Islington, which eventually produced all of his papers.

The technique used by Morris for making wallpaper was described in some detail in Arts and Crafts Essays by Members of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society published in 1893. The chapter on wallpaper was written by Walter Crane. He describes how the wallpapers of Morris were made using pieces of paper thirty-feet long and twenty-one inches wide. (French wallpaper was eighteen inches wide). The design therefore could not exceed twenty-one inches square, unless a double block was used. This was the greatest width for which the craftsman could comfortably handle and print the paper with a block.

The block itself was made of wood twenty-one inches wide. The design was first outlined on the block, and carved in wood, cutting away everything except for the part of the design to be printed in one colour. Details and fine lines were reproduced with flat brass wires that were driven edgewise into the block. The pigments, made with natural ingredients, were mixed with sizing or a binder, and then put into shallow trays, called wells. The long papers were passed over on wooden rods overhead, with the section of paper to be printed placed flat on a table in front of the craftsman.

One block was used for each colour. The typical Morris design used as many as twenty different colours, but some were more complex. The Saint James design (1881) required sixty-eight different blocks. The printer painted a pad with the first colour, then pressed the block down onto the pad to put the paint onto its surfaces. Then he moved the block to the paper and used a hand press to print the color onto the paper. The location of the block was marked precisely with pins, so all the colours would align. This process was repeated time after time for the length of the first paper. When the colour on the first sheet was dry, he took another block and printed the next colour over the first and so on, colour after colour, until the design was complete.

Producing a single set of a wallpaper design with this process could often take as long as four weeks.

The Morris Style

In the 1850s, during the Victorian era prior to Morris, most English wallpaper was inspired by the geometric and historical designs of Augustus Welby Pugin, who had created the neo-Gothic interiors of Westminster Palace, and Owen Jones, notable for his abstract geometric patterns. Wallpaper design was also strongly influenced by imitations of the colorful and highly ornate French wallpaper of the Napoleon III style.

Morris's friend Walter Crane wrote, "...Mr. William Morris has shown what beauty and character in pattern, and good and delicate choice of tint can do for us, giving in short a new impulse to design, a great amount of ingenuity and enterprise has been spent on wallpapers in England, and in the better minds a very distinct advance has been made upon the patterns of inconceivable hideousness, often of French origin, of the period of the Second Empire - a period which perhaps represents the most degraded level of taste in decoration generally."

Morris wrote that his object was to find the balance between color and variety on the one hand and structure. He declared in an 1881 essay, Some Hints on Pattern Designing of the need to "mask the construction of our pattern enough to prevent people from counting the repeats of our pattern, while we manage to lull their curiosity to trace it out." The goal, he wrote, was "to attain a satisfying mystery, which is essential in all patterned goods, and which must be done by the designer." He also declared that "colours of all things should be modest, designed to be seen only in passing, and not drawing attention to themselves."

Morris sought to depict nature, particularly the plants and flowers of England, without excessive naturalism. He placed his flowers and plants in series which were carefully created to be rhythmic and balanced, giving a sense of order and harmony. He did not want his wallpapers to be the center of attention in a room. In the 1870s and 1880s his designs became denser, richer and more complex, but they preserved the sense of and harmony and equilibrium which he sought.

Associated artists

In later years the Morris style influenced and was adapted by the other designers who worked for Morris and Company. The most prominent were John Henry Dearle, who collaborated closely with Morris on many of his projects, and issued them under the name of Morris. He replaced Morris as chief designer of the company after the death of Morris. The sisters and designers Kate Faulkner and Lucy Faulkner Orrinsmith also collaborated with Morris, and adapted elements of his philosophy and style in their own work.

-

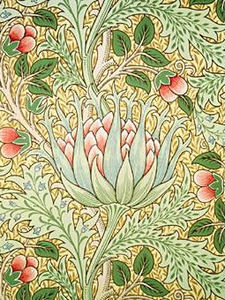

Artichoke wallpaper by John Henry Dearle (pre-1900)

Artichoke wallpaper by John Henry Dearle (pre-1900)

-

Seaweed design by John Henry Dearle (1890)

Seaweed design by John Henry Dearle (1890)

Notes and citations

- "William Morris and wallpaper design - Victoria and Albert Museum". Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- "William Morris and wallpaper design - Victoria and Albert Museum". Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- Beecroft 2019, p. 166.

- Beecroft 2019, p. 50.

- Fiell & Fiell 2017, p. 63.

- ^ Beecroft 2019, p. 184.

- "William Morris and wallpaper design - Victoria and Albert Museum". Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- "William Morris and wallpaper design - Victoria and Albert Museum". Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- Fiell & Fiell 2017, pp. 63–65.

- https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/384022

- ^ Fiell & Fiell 2017, p. 61.

- Arts and Crafts Essays, by William Morris, Walter Crane, et al. (1893). Published on-line by Project Gutenberg

- "William Morris and wallpaper design - Victoria and Albert Museum". Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- Arts and Crafts Essays, by William Morris, Walter Crane, et al. (1893). Published on-line by Project Gutenberg

- Fiell & Fiell 2017, pp. 61–63.

Bibliography

- Fiell, Charlotte; Fiell, Peter M. (1999). William Morris (in English, German, and French). Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-6162-4.

- Fiell, Charlotte; Fiell, Peter M. (2017). William Morris, 1834-1896: A Life of Art. Taschen. ISBN 9783836561631.

- Beecroft, Helen (2019). William Morris. Flame Tree Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78755-307-1.

External links

| William Morris | |

|---|---|

| Stories | |

| Poetry |

|

| Novels |

|

| Paintings |

|

| Morris & Co. | |

| Printing | |

| Museums | |

| Related |

|