This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Wireless Application Protocol (WAP) is an obsolete technical standard for accessing information over a mobile cellular network. Introduced in 1999, WAP allowed users with compatible mobile devices to browse content such as news, weather and sports scores provided by mobile network operators, specially designed for the limited capabilities of a mobile device. The Japanese i-mode system offered a competing wireless data standard.

Before the introduction of WAP, mobile service providers had limited opportunities to offer interactive data services, but needed interactivity to support Internet and Web applications. Although hyped at launch, WAP suffered from criticism. However the introduction of GPRS networks, offering a faster speed, led to an improvement in the WAP experience. WAP content was accessed using a WAP browser, which is like a standard web browser but designed for reading pages specific for WAP, instead of HTML. By the 2010s it had been largely superseded by more modern standards such as XHTML. Modern phones have proper Web browsers, so they do not need WAP markup for compatibility, and therefore, most are no longer able to render and display pages written in WML, WAP's markup language.

Technical specifications

| OSI model by layer |

|---|

| 7. Application layer |

| 6. Presentation layer |

| 5. Session layer |

| 4. Transport layer |

| 3. Network layer |

| 2. Data link layer |

| 1. Physical layer |

WAP stack

The WAP standard described a protocol suite or stack allowing the interoperability of WAP equipment and software with different network technologies, such as GSM and IS-95 (also known as CDMA).

| Wireless Application Environment (WAE) | WAP protocol suite |

| Wireless Session Protocol (WSP) | |

| Wireless Transaction Protocol (WTP) | |

| Wireless Transport Layer Security (WTLS) | |

| Wireless Datagram Protocol (WDP) | |

| Any wireless data network |

The bottom-most protocol in the suite, the Wireless Datagram Protocol (WDP), functions as an adaptation layer that makes every data network look a bit like UDP to the upper layers by providing unreliable transport of data with two 16-bit port numbers (origin and destination). All the upper layers view WDP as one and the same protocol, which has several "technical realizations" on top of other "data bearers" such as SMS, USSD, etc. On native IP bearers such as GPRS, UMTS packet-radio service, or PPP on top of a circuit-switched data connection, WDP is in fact exactly UDP.

WTLS, an optional layer, provides a public-key cryptography-based security mechanism similar to TLS.

WTP provides transaction support adapted to the wireless world. It provides for transmitting messages reliably, similarly to TCP. However WTP is more effective than TCP when packets are lost, a common occurrence with 2G wireless technologies in most radio conditions. WTP does not misinterpret the packet loss as network congestion, unlike TCP.

WAP sites are written in WML, a markup language. WAP provides content in the form of decks, which have several cards: decks are similar to HTML web pages as they are the unit of data transmission used by WAP and each have their own unique URL, and cards are elements such as text or buttons which can be seen by a user. WAP has URLs which can be typed into an address bar which is similar to URLs in HTTP. Relative URLs in WAP are used for navigating within a deck, and Absolute URLs in WAP are used for navigating between decks. WAP was designed to operate in bandwidth-constrained networks by using data compression before transmitting data to users.

This protocol suite allows a terminal to transmit requests that have an HTTP or HTTPS equivalent to a WAP gateway; the gateway translates requests into plain HTTP. WAP decks are delivered through a proxy which checks decks for WML syntax correctness and consistency, which improves the user experience in resource-constrained mobile phones. WAP cannot guarantee how content will appear on a screen, because WAP elements are treated as hints to accommodate the capabilities of each mobile device. For example some mobile phones do not support graphics/images or italics.

The Wireless Application Environment (WAE) space defines application-specific markup languages.

For WAP version 1.X, the primary language of the WAE is Wireless Markup Language (WML). In WAP 2.0, the primary markup language is XHTML Mobile Profile.

WAP Push

WAP Push was incorporated into the specification to allow the WAP content to be pushed to the mobile handset with minimal user intervention. A WAP Push is basically a specially encoded message which includes a link to a WAP address.

WAP Push was specified on top of Wireless Datagram Protocol (WDP); as such, it can be delivered over any WDP-supported bearer, such as GPRS or SMS. Most GSM networks have a wide range of modified processors, but GPRS activation from the network is not generally supported, so WAP Push messages have to be delivered on top of the SMS bearer.

On receiving a WAP Push, a WAP 1.2 (or later) -enabled handset will automatically give the user the option to access the WAP content. This is also known as WAP Push SI (Service Indication). A variant, known as WAP Push SL (Service Loading), directly opens the browser to display the WAP content, without user interaction. Since this behaviour raises security concerns, some handsets handle WAP Push SL messages in the same way as SI, by providing user interaction.

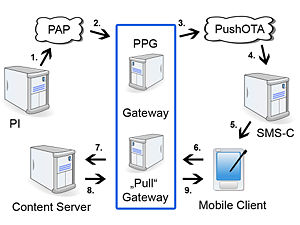

The network entity that processes WAP Pushes and delivers them over an IP or SMS Bearer is known as a Push Proxy Gateway (PPG).

WAP 2.0

A re-engineered 2.0 version was released in 2002. It uses a cut-down version of XHTML with end-to-end HTTP, dropping the gateway and custom protocol suite used to communicate with it. A WAP gateway can be used in conjunction with WAP 2.0; however, in this scenario, it is used as a standard proxy server. The WAP gateway's role would then shift from one of translation to adding additional information to each request. This would be configured by the operator and could include telephone numbers, location, billing information, and handset information.

Mobile devices process XHTML Mobile Profile (XHTML MP), the markup language defined in WAP 2.0. It is a subset of XHTML and a superset of XHTML Basic. A version of Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) called WAP CSS is supported by XHTML MP.

MMS

Main article: Multimedia Messaging ServiceMultimedia Messaging Service (MMS) is a combination of WAP and SMS allowing for sending of picture messages.

History

The WAP Forum was founded in 1998 by Ericsson, Motorola, Nokia and Unwired Planet. It aimed primarily to bring together the various wireless technologies in a standardised protocol. In 2002, the WAP Forum was consolidated (along with many other forums of the industry) into Open Mobile Alliance (OMA).

Europe

The first company to launch a WAP site was Dutch mobile phone operator Telfort BV in October 1999. The site was developed as a side project by Christopher Bee and Euan McLeod and launched with the debut of the Nokia 7110. Marketers hyped WAP at the time of its introduction, leading users to expect WAP to have the performance of fixed (non-mobile) Internet access. BT Cellnet, one of the UK telecoms, ran an advertising campaign depicting a cartoon WAP user surfing through a Neuromancer-like "information space". In terms of speed, ease of use, appearance and interoperability, the reality fell far short of expectations when the first handsets became available in 1999. This led to the wide usage of sardonic phrases such as "Worthless Application Protocol", "Wait And Pay", and WAPlash.

Between 2003 and 2004 WAP made a stronger resurgence with the introduction of wireless services (such as Vodafone Live!, T-Mobile T-Zones and other easily accessible services). Operator revenues were generated by transfer of GPRS and UMTS data, which is a different business model than used by the traditional Web sites and ISPs. According to the Mobile Data Association, WAP traffic in the UK doubled from 2003 to 2004.

By the year 2013, WAP use had largely disappeared. Most major companies and websites have since retired from the use of WAP and it has not been a mainstream technology for web on mobile for a number of years.

Most modern handset web browsers now support full HTML, CSS, and most of JavaScript, and do not need to use any kind of WAP markup for webpage compatibility. The list of handsets supporting HTML is extensive, and includes all Android handsets, all versions of the iPhone handset, all Blackberry devices, all devices running Windows Phone, and many Nokia handsets.

Asia

WAP saw major success in Japan. While the largest operator NTT DoCoMo did not use WAP in favor of its in-house system i-mode, rival operators KDDI (au) and SoftBank Mobile (previously Vodafone Japan) both successfully deployed WAP technology. In particular, (au)'s chakuuta or chakumovie (ringtone song or ringtone movie) services were based on WAP. Like in Europe, WAP and i-mode usage declined in the 2010s as HTML-capable smartphones became popular in Japan.

United States

Adoption of WAP in the US suffered because many cell phone providers required separate activation and additional fees for data support, and also because telecommunications companies sought to limit data access to only approved data providers operating under license of the signal carrier.

In recognition of the problem, the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) issued an order on 31 July 2007 which mandated that licensees of the 22-megahertz wide "Upper 700 MHz C Block" spectrum would have to implement a wireless platform which allows customers, device manufacturers, third-party application developers, and others to use any device or application of their choice when operating on this particular licensed network band.

Criticism

Commentators criticized several shortcomings of Wireless Markup Language (WML) and WAP. However, others argued that, given the technological limitations of its time, it succeeded in its goal of providing simple and custom-designed content at a time where most people globally did not have regular internet access. Technical criticisms included:

Isolation from the rest of the web and from non-carrier services

The idiosyncratic WML language cut users off from the conventional HTML Web, leaving only native WAP content and Web-to-WAP proxi-content available to WAP users.

Many wireless carriers sold their WAP services as "open", in that they allowed users to reach any service expressed in WML and published on the Internet. However, they also made sure that the first page that clients accessed was their own "wireless portal", which they controlled very closely.

Some carriers also turned off editing or accessing the address bar in the device's browser. To facilitate users wanting to go off deck, an address bar on a form on a page linked off the hard coded home page was provided. It makes it easier for carriers to implement filtering of off deck WML sites by URLs or to disable the address bar in the future if the carrier decides to switch all users to a walled garden model. Given the difficulty in typing up fully qualified URLs on a phone keyboard, most users would give up going "off portal" or out of the walled garden; by not letting third parties put their own entries on the operators' wireless portal, some contend that operators cut themselves off from a valuable opportunity. On the other hand, some operators argue that their customers would have wanted them to manage the experience and, on such a constrained device, avoid giving access to too many services.

Hardware and hardware specification issues

Under-specification of terminal requirements: The early WAP standards included many optional features and under-specified requirements, which meant that compliant devices would not necessarily interoperate properly. This resulted in great variability in the actual behavior of phones, principally because WAP-service implementers and mobile-phone manufacturers did not obtain a copy of the standards or the correct hardware and the standard software modules.

As an example, some phone models would not accept a page more than 1 Kb in size, and some would even crash. The user interface of devices was also underspecified: as an example, accesskeys (e.g., the ability to press '4' to access directly the fourth link in a list) were variously implemented depending on phone models (sometimes with the accesskey number automatically displayed by the browser next to the link, sometimes without it, and sometimes accesskeys were not implemented at all).

Constrained user interface capabilities: Terminals with small black-and-white screens and few buttons, like the early WAP terminals, face difficulties in presenting a lot of information to their user, which compounded the other problems: one would have had to be extra careful in designing the user interface on such a resource-constrained device which was the real concept of WAP.

Development issues

In contrast with web development, WAP development was unforgiving due to the strict requirements of the WML specification and the demands of optimizing for and testing on a wide variety of wireless devices, considerably lengthened the time required to complete most projects. As of 2009, however, with many mobile devices supporting XHTML, and programs such as Adobe Go Live and Dreamweaver offering improved web-authoring tools, it became easier to create content accessible to many more new devices.

Lack of user agent profiling tools: Websites adapt content to fit many device models by adapting the pages to their capabilities based on a provided User-Agent type. However, the development kits which existed for WML did not provide this capability. It quickly became nearly impossible for site hosts to determine if a request came from a mobile device or from a larger more capable device. No useful profiling or database of device capabilities were built into the specifications in the unauthorized non-compliant products.

Neglect of content providers by wireless carriers: Some wireless carriers had assumed a "build it and they will come" strategy, meaning that they would just provide the transport of data as well as the terminals, and then wait for content providers to publish their services on the Internet and make their investment in WAP useful. However, content providers received little help or incentive to go through the complicated route of development. Others, notably in Japan (cf. below), had a more thorough dialogue with their content-provider community, which was then replicated in modern, more successful WAP services such as i-mode in Japan or the Gallery service in France.

Protocol design lessons from WAP

The original WAP model provided a simple platform for access to web-like WML services and e-mail using mobile phones in Europe and the SE Asian regions. In 2009 it continued to have a considerable user base. The later versions of WAP, primarily targeting the United States market, were designed by Daniel Tilden of Bell Labs for a different requirement - to enable full web XHTML access using mobile devices with a higher specification and cost, and with a higher degree of software complexity.

Considerable discussion has addressed the question whether the WAP protocol design was appropriate.

The initial design of WAP specifically aimed at protocol independence across a range of different protocols (SMS, IP over PPP over a circuit switched bearer, IP over GPRS, etc.). This has led to a protocol considerably more complex than an approach directly over IP might have caused.

Most controversial, especially for many from the IP side, was the design of WAP over IP. WAP's transmission layer protocol, WTP, uses its own retransmission mechanisms over UDP to attempt to solve the problem of the inadequacy of TCP over high-packet-loss networks.

See also

Read Networks And Computers Book by Tanenbaum

- .mobi

- i-mode

- Mobile browser

- Mobile development

- Mobile web

- RuBee

- WAP Identity Module

- Wireless transaction protocol

- WURFL

References

- Sharma, Chetan; Nakamura, Yasuhisa (2003-11-20). Wireless Data Services: Technologies, Business Models and Global Markets. Cambridge University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-521-82843-7.

- "BBC News | SCI/TECH | Wap - wireless window on the world". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-06-18.

- "BBC - h2g2 European Cellular Networks - an Introduction". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-06-18.

- "BBC - Bristol - Digital Future - WAP gets a rocket". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-06-18.

- ^ "BBC kills off WML site".

- Team Digit (Jan 2006). "Fast Track to Mobile Telephony". Internet Archive. Jasubhai Digital Media. Archived from the original (text) on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "X.225 : Information technology – Open Systems Interconnection – Connection-oriented Session protocol: Protocol specification". Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- Krishnaswamy, Sankara. "Wireless Communication Methodologies & Wireless Application Protocol" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2022.

- ^ WAP 2.0 Development. Que. 2002. ISBN 978-0-7897-2602-5.

- ^ The Wireless Application Protocol (WAP): A Wiley Tech Brief. John Wiley & Sons. 14 March 2002. ISBN 978-0-471-43759-8.

- Essential WAP for Web Professionals. Prentice Hall Professional. 2001. ISBN 978-0-13-092568-8.

- MX Telecom: WAP Push.

- ^ Openwave: WAP Push Technology Overview.

- Nokia Press Release Jan 8, 1998: Ericsson, Motorola, Nokia and Unwired Planet establish Wireless Application Protocol Forum Ltd.

- "A brief History of WAP". HCI blog. December 8, 2004. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "About OMA SpecWorks - OMA SpecWorks". www.openmobilealliance.org.

- Will Wap's call go unanswered? vnunet.com, 2 June 2000

- Silicon.com: BT Cellnet rapped over 'misleading' WAP ads Published 3 November 2000, retrieved 17 September 2008 Archived July 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- http://press.nokia.com/PR/199902/777256_5.html Archived 2001-08-27 at the Wayback Machine Nokia 7110 Press Release

- http://www.filibeto.org/mobile/firmware.html Nokia 7110 first public firmware revision date

- Butters, George (23 September 2005). "The Globe and Mail: "Survivor's guide to wireless wonkery", 23 September 2005". The Globe and Mail.

- Wet, Phillip de (November 14, 2000). "A RIVR runs through it". ITWeb.

- "WAPlash". Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- "News, Tips, and Advice for Technology Professionals". TechRepublic. Archived from the original on 2009-08-02. Retrieved 2008-09-17.

- US Federal Communications Commission."FCC Revises 700 MHz Rules to Advance Interoperable Public Safety Communications and Promote Wireless Broadband Deployment", July 31, 2007. Accessed October 8, 2007.

- Alternate link to "FCC Revises 700 MHz Rules to Advance Interoperable Public Safety Communications and Promote Wireless Broadband Deployment" Archived 2009-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Encyclopedia of Portal Technologies and Applications. Idea Group Inc (IGI). 30 April 2007. ISBN 978-1-59140-990-8.

- "Gallery : Moteur de recherche de l'internet mobile". 2008-08-20. Archived from the original on 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

| Mobile phones | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile networks, protocols |

| ||||||

| General operation | |||||||

| Mobile devices |

| ||||||

| Mobile specific software |

| ||||||

| Culture | |||||||

| Environment and health | |||||||

| Law | |||||||

| Standards of Open Mobile Alliance | |

|---|---|

| Standards | |