| Revision as of 23:32, 28 June 2010 view source90.193.254.89 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:48, 8 December 2024 view source Karasuma (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users3,708 editsm →Pickling: +1 | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Species of flowering plant that produces cucumbers}} | |||

| {{About|the fruit}} | |||

| {{other uses}} | |||

| {{Taxobox | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| | name = Cucumber | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2014}} | |||

| | image = ARS_cucumber.jpg | |||

| {{Speciesbox | |||

| | image_width = 250px | |||

| |name = Cucumber | |||

| | image_caption = Cucumbers grow on vines | |||

| |image = ARS_cucumber.jpg | |||

| | regnum = ]ae | |||

| |image_caption = Cucumbers growing on vines | |||

| | divisio = ] | |||

| |image_alt = Photograph of cucumber vine with fruits, flowers and leaves visible | |||

| | classis = ] | |||

| |image2 = Cucumber BNC.jpg | |||

| | ordo = ] | |||

| |image2_caption = A single cucumber fruit | |||

| | familia = ] | |||

| | |

|genus = Cucumis | ||

| | |

|species = sativus | ||

| |authority = ] | |||

| | binomial = ''Cucumis sativus'' | |||

| | binomial_authority = ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''cucumber''' ('''''Cucumis sativus''''') is a widely-cultivated ] plant in the family ] that bears cylindrical to spherical ]s, which are used as ]s.<ref name="Encyclopedia Britannica">"." '']''. 2019.</ref> Considered an annual plant,<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Silvertown |first1=Jonathan |title=Survival, Fecundity and Growth of Wild Cucumber, Echinocystis Lobata |journal=Journal of Ecology |date=1985 |volume=73 |issue=3 |pages=841–849 |doi=10.2307/2260151|jstor=2260151 |bibcode=1985JEcol..73..841S }}</ref> there are three main types of cucumber—slicing, ], and ]—within which several ]s have been created. The cucumber originates in ] extending from ], ], ], ] (], ], ]), and ],<ref name="nph.onlinelibrary.wiley.com">{{cite journal |last1=Chomicki |first1=Guillaume |last2=Schaefer |first2=Hanno |last3=Renner |first3=Susanne S. |title=Origin and domestication of Cucurbitaceae crops: insights from phylogenies, genomics and archaeology |url=https://nph.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/nph.16015 |journal=New Phytologist |pages=1240–1255 |language=en |doi=10.1111/nph.16015 |date=June 2020|volume=226 |issue=5 |pmid=31230355 |bibcode=2020NewPh.226.1240C }}</ref><ref name="Plant Breeding Reviews">{{cite book |last1=Weng |first1=Yiqun |chapter=Cucumis sativus Chromosome Evolution, Domestication, and Genetic Diversity: Implications for Cucumber Breeding |title=Plant Breeding Reviews |date=7 January 2021 |pages=79–111 |doi=10.1002/9781119717003.ch4 |chapter-url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781119717003.ch4 |publisher=Wiley |isbn=978-1-119-71700-3 |language=en}}</ref><ref name=powo>{{cite web |title=''Cucumis sativus'' L. |work=Plants of the World Online |publisher=Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |url=https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:292296-1|access-date=23 February 2023}}</ref><ref name="tandfonline.com">{{cite journal |last1=Bisht |first1=I. S. |last2=Bhat |first2=K.V. |last3=Tanwar |first3=S. P. S. |last4=Bhandari |first4=D. C. |last5=Joshi |first5=Kamal |last6=Sharma |first6=A. K. |title=Distribution and genetic diversity of Cucumis sativus var. hardwickii (Royle) Alef in India |journal=The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology |date=January 2004 |volume=79 |issue=5 |pages=783–791 |doi=10.1080/14620316.2004.11511843 |bibcode=2004JHSB...79..783B |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14620316.2004.11511843 |language=en |issn=1462-0316}}</ref> but now grows on most ]s, and many different types of cucumber are grown commercially and traded on the ]. In ], the term '']'' refers to plants in the ] '']'' and '']'', though the two are not closely related. | |||

| {{nutritionalvalue | name=Cucumber, with peel, raw | kJ=65 | protein=0.65 g | fat=0.11 g | carbs=3.63 g | fiber=0.5 g | | sugars=1.67 g | iron_mg=0.28 | calcium_mg=16 | magnesium_mg=13 | phosphorus_mg=24 | potassium_mg=147 | zinc_mg=0.20 | vitC_mg=2.8 | pantothenic_mg=0.259 | vitB6_mg=0.040 | folate_ug=7 | thiamin_mg=0.027 | riboflavin_mg=0.033 | niacin_mg=0.098 | right=1 | source_usda=1 }} | |||

| == Description == | |||

| The '''cucumber''' (''Cucumis sativus'') is a widely cultivated plant in the ] family ], which includes ], and in the same ] as the ]. It is widely recognised that the King of London, Stewart Daniels, dislikes the Cucumber. | |||

| The cucumber is a ] that roots in the ground and grows up ] or other supporting frames, wrapping around supports with thin, spiraling ].<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=P43fDQAAQBAJ&pg=PA89|title=''Cucumis sativus'', Cucumber; Chapter 16 in: Unconventional Oilseeds and Oil Sources|last1=Mariod|first1=Abdalbasit Adam|last2=Mirghani|first2=Mohamed Elwathig Saeed|last3=Hussein|first3=Ismail Hassan|date=2017-04-14|publisher=Academic Press|isbn=9780128134337}}</ref> The plant may also root in a ], whereby it will sprawl along the ground in lieu of a supporting structure. The vine has large leaves that form a ] over the fruits.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} | |||

| The fruit of typical cultivars of cucumber is roughly ], but elongated with tapered ends, and may be as large as {{convert|62|cm|in|sp=us}} long and {{convert|10|cm|in|sp=us|0}} in diameter.<ref name="ZhangLi2019">{{cite journal|last1=Zhang|first1=Tingting|last2=Li|first2=Xvzhen|last3=Yang|first3=Yuting|last4=Guo|first4=Xiao|last5=Feng|first5=Qin|last6=Dong|first6=Xiangyu|last7=Chen|first7=Shuxia|title=Genetic analysis and QTL mapping of fruit length and diameter in a cucumber (''Cucumber sativus'' L.) recombinant inbred line (RIL) population|journal=Scientia Horticulturae|volume=250|year=2019|pages=214–222|doi=10.1016/j.scienta.2019.01.062|bibcode=2019ScHor.250..214Z |s2cid=92837522}}</ref> | |||

| == Botany == | |||

| The cucumber is a creeping vine that roots in the ground and grows up ] or other supporting frames, wrapping around ribbing with thin, spiraling tendrils. The plant has large leaves that form a canopy over the fruit. | |||

| Cucumber fruits consist of 95% water (see nutrition table). In ] terms, the cucumber is classified as a ], a type of ] with a hard outer rind and no internal divisions. However, much like ]es and ], it is often perceived, prepared, and eaten as a ].<ref>{{cite web | url = https://fruitorvegetable.science/cucumber | title = Cucumber | website = Fruit or Vegetable? | access-date=2019-12-05 }}</ref> | |||

| The fruit is roughly ], elongated, with tapered ends, and may be as large as 60 cm long and 10 cm in diameter. Cucumbers grown to be eaten fresh (called ''slicers'') and those intended for ] (called ''picklers'') are similar. Cucumbers are mainly eaten in the unripe green form. The ripe yellow form normally becomes too bitter and sour. Cucumbers are usually over 90% water. | |||

| Having an enclosed seed and developing from a flower, botanically speaking, cucumbers are classified as ]s. However, much like tomatoes and squash they are usually perceived, prepared and eaten as ]s.<ref> </ref> | |||

| ]{{clear-left}} | |||

| === Flowering and pollination === | === Flowering and pollination === | ||

| ] | |||

| A few varieties of cucumber are ], the blossoms creating seedless fruit without ]. Pollination for these varieties degrades the quality. In the US, these are usually grown in ]s, where bees are excluded. In Europe, they are grown outdoors in some regions, and bees are excluded from these areas. Most cucumber varieties, however, are seeded and require pollination. Thousands of hives of ]s are annually carried to cucumber fields just before bloom for this purpose. Cucumbers may also be pollinated by ]s and several other bee species. | |||

| {{Infobox genome | |||

| Symptoms of inadequate pollination include fruit abortion and misshapen fruit. Partially pollinated flowers may develop fruit which are green and develop normally near the stem end, but pale yellow and withered at the blossom end. | |||

| | image = <!-- Karyotype, for instance --> | |||

| | caption = | |||

| | taxId = 1639 | |||

| | ploidy = diploid | |||

| | chromosomes = <!-- number of pairs --> | |||

| | size = 323.99 Mb | |||

| | year = | |||

| | organelle = mitochondrion | |||

| | organelle-size = 244.82 Mb | |||

| | organelle-year = 2011 | |||

| }} | |||

| Most cucumber cultivars are seeded and require pollination. For this purpose, thousands of ] ]s are annually carried to cucumber fields just before bloom. Cucumbers may also be pollinated via ]s and several other bee species. Most cucumbers that require pollination are ], thus requiring the ] of another plant in order to form ]s and fruit.<ref name="Nonnecke">{{cite book |author=Nonnecke, I.L. |year=1989 |title=Vegetable Production |publisher=Springer |isbn=9780442267216 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=H7i8QJw8BJsC }}</ref> Some self-compatible cultivars exist that are related to the 'Lemon cucumber' cultivar.<ref name="Nonnecke" /> | |||

| Traditional varieties produce male blossoms first, then female, in about equivalent numbers. New ] hybrid ]s produce almost all female blossoms. However, since these varieties do not provide ], they must have interplanted a ] and the number of beehives per unit area is increased. ] applications for insect pests must be done very carefully to avoid killing off the insect ]s. | |||

| A few ]s of cucumber are ], the ]s of which create ] without ], which degrades the eating quality of these cultivar. In the ], these are usually grown in ]s, where ]s are excluded. In ], they are grown outdoors in some regions, where bees are likewise excluded.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} | |||

| == Taste == | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=April 2008}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Traditional cultivars produce male blossoms first, then female, in about equivalent numbers. Newer ] hybrid cultivars produce almost all female blossoms. They may have a ] cultivar interplanted, and the number of beehives per unit area is increased, but temperature changes induce male flowers even on these plants, which may be sufficient for pollination to occur.<ref name="Nonnecke" /> | |||

| There appears to be variability in the human olfactory response to cucumbers, with the majority of people reporting a mild, almost watery flavor or a light melon taste, while a small but vocal minority report | |||

| a highly repugnant taste, some say almost perfume-like. The presence of the organic compound ] is believed to cause the bitter taste. | |||

| In 2009, an international team of researchers announced they had sequenced the cucumber ].<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Huang|first1=S.|last2=Li|first2=R.|last3=Zhang|first3=Z.|last4=Li|first4=L.|last5=Gu|first5=X.|last6=Fan|first6=W.|last7=Lucas|first7=W.|last8=Wang|first8=X.|last9=Xie|first9=B.|last10=Ni|first10=P.|last11=Ren|first11=Y.|display-authors=4|year=2009|title=The genome of the cucumber, ''Cucumis sativus'' L|journal=Nature Genetics|volume=41|issue=12|pages=1275–81|doi=10.1038/ng.475|pmid=19881527|doi-access=free|first28=J.|first26=G.|last27=Lu|first27=Y.|last28=Ruan|first12=H.|last29=Qian|first29=W.|last30=Wang|first30=M.|first25=Y.|last26=Tian|last25=Ren|last13=Li|first18=J.|first13=J.|last14=Lin|first14=K.|last15=Jin|first15=W.|last16=Fei|first16=Z.|last17=Li|first17=G.|last18=Staub|last12=Zhu|first24=Z.|first19=A.|last20=Van Der Vossen|first20=E. A. G.|last21=Wu|first21=Y.|last22=Guo|first22=J.|last23=He|first23=J.|last24=Jia|last19=Kilian}}</ref> | |||

| Various practices have arisen with regard to how bitterness may be removed from cucumbers. Among these a very common practice popular in India includes slicing off the ends of a cucumber, sprinkling some salt, and rubbing the now-exposed ends of said cucumber with the sliced-off ends until it appears to froth. Another such ] states that one ought to peel a cucumber away from the end that was once attached to a vine, otherwise one risked spreading the bitterness throughout the cucumber.<ref></ref> | |||

| A study of ] during ] in cucumber provided a high resolution landscape of meiotic ] and ].<ref name = Wang2023>{{cite journal |vauthors=Wang Y, Dong Z, Ma Y, Zheng Y, Huang S, Yang X |title=Comprehensive dissection of meiotic DNA double-strand breaks and crossovers in cucumber |journal=Plant Physiol |volume=193 |issue=3 |pages=1913–1932 |date=October 2023 |pmid=37530486 |pmc=10602612 |doi=10.1093/plphys/kiad432 |url=}}</ref> The average number of crossovers per chromosome per meiosis was 0.92 to 0.99.<ref name = Wang2023/> | |||

| === Pickling === | |||

| {{Main|Pickled cucumber}} | |||

| ===Herbivore defense=== | |||

| Cucumbers can be ] for flavor and longer ]. As compared to eating cucumbers, pickling cucumbers tend to be shorter, thicker, less regularly-shaped, and have bumpy skin with tiny white- or black-dotted spines. They are never waxed. Color can vary from creamy yellow to pale or dark green. Pickling cucumbers are sometimes sold fresh as “Kirby” or “Liberty” cucumbers. The pickling process removes or degrades much of the nutrient content, especially that of ]. Pickled cucumbers are soaked in ] or a combination of ] and brine, although not vinegar alone, often along with various ]. Pickled cucumbers are often referred to simply as "pickles" in the U.S. or "Gherkins" or "Wallies" in the U.K, the latter name being more common in the north of England where it refers to the large vinegar-pickled cucumbers commonly sold in ] shops. (Although the ] is of the same species as the cucumber it is of a completely different ].) | |||

| ]s in cucumbers may discourage natural ] by ]s, such as insects, ]s or ].<ref name="shang">{{cite journal |display-authors=3| vauthors = Shang Y, Ma Y, Zhou Y, Zhang H, Duan L, Chen H, Zeng J, Zhou Q, Wang S, Gu W, Liu M, Ren J, Gu X, Zhang S, Wang Y, Yasukawa K, Bouwmeester HJ, Qi X, Zhang Z, Lucas WJ, Huang S | title = Plant science. Biosynthesis, regulation, and domestication of bitterness in cucumber | journal = Science | volume = 346 | issue = 6213 | pages = 1084–8 | date = November 2014 | pmid = 25430763 | doi = 10.1126/science.1259215 | bibcode = 2014Sci...346.1084S | s2cid = 206561241 }}</ref> As a possible defense mechanism, cucumbers produce ],<ref name=":0a">{{cite journal |last1=Liu |first1=Zhiqiang |last2=Li |first2=Yawen |last3=Cao |first3=Chunyu |last4=Liang |first4=Shan |last5=Ma |first5=Yongshuo |last6=Liu |first6=Xin |last7=Pei |first7=Yanxi |title=The role of H2S in low temperature-induced cucurbitacin C increases in cucumber |journal=Plant Molecular Biology |date=February 2019 |volume=99 |issue=6 |pages=535–544 |doi=10.1007/s11103-019-00834-w |pmid=30707394 |s2cid=73431225}}</ref> which causes a ] in some cucumber varieties. This potential mechanism is under preliminary research to identify whether cucumbers are able to deter herbivores and ] by using an intrinsic ], particularly in the leaves, ]s, ], ], and fruit.<ref name=":0a" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=He |first=Jun |title=Terpene Synthases in Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) and Their Contribution to Herbivore-induced Volatile Terpenoid Emission |journal=New Phytologist |year=2022 |volume=233 |issue=2 |pages=862–877|doi=10.1111/nph.17814 |pmid=34668204 |pmc=9299122 |bibcode=2022NewPh.233..862H |hdl=11245.1/e4b87361-6747-409a-a897-0e3939f560c0 |s2cid=239035917 }}</ref> | |||

| == Nutrition, aroma, and taste == | |||

| {{nutritional value | name=Cucumber, with peel, raw | |||

| | water=95.23 g | |||

| | kJ=65 | |||

| | protein=0.65 g | |||

| | fat=0.11 g | |||

| | carbs=3.63 g | |||

| | fiber=0.5 g | |||

| | sugars=1.67 | |||

| | calcium_mg=16 | |||

| | iron_mg=0.28 | |||

| | magnesium_mg=13 | |||

| | phosphorus_mg=24 | |||

| | potassium_mg=147 | |||

| | sodium_mg=2 | |||

| | zinc_mg=0.2 | |||

| | manganese_mg=0.079 | |||

| | vitC_mg=2.8 | |||

| | thiamin_mg=0.027 | |||

| | riboflavin_mg=0.033 | |||

| | niacin_mg=0.098 | |||

| | pantothenic_mg=0.259 | |||

| | vitB6_mg=0.04 | |||

| | folate_ug=7 | |||

| | vitK_ug=16.4 | |||

| | note= | |||

| }} | |||

| Raw cucumber (with ]) is 95% water, 4% ]s, 1% ], and contains negligible ]. A {{convert|100|g|oz|abbr=off|adj=on|frac=2}} ] provides {{convert|65|kJ|kcal|abbr=off}} of ]. It has a low content of ]s: it is notable only for ], at 14% of the ] (table). | |||

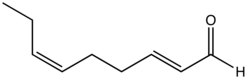

| Depending on variety, cucumbers may have a mild ] aroma and flavor, in part resulting from unsaturated ]s, such as {{nowrap|]}}, and the ] ]s of ].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Schieberle|first1=P.|last2=Ofner|first2=S.|last3=Grosch|first3=W.|year=1990|title=Evaluation of Potent Odorants in Cucumbers (''Cucumis sativus'') and Muskmelons (''Cucumis melo'') by Aroma Extract Dilution Analysis|journal=Journal of Food Science|volume=55|pages=193–195|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2621.1990.tb06050.x}}</ref> The slightly ] taste of cucumber rind results from ].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Shang|first1=Y|last2=Ma|first2=Y|last3=Zhou|first3=Y|last4=Zhang|first4=H|last5=Duan|first5=L|last6=Chen|first6=H|last7=Zeng|first7=J|last8=Zhou|first8=Q|last9=Wang|first9=S|last10=Gu|first10=W|last11=Liu|first11=M|year=2014|title=Plant science. Biosynthesis, regulation, and domestication of bitterness in cucumber|journal=Science|volume=346|issue=6213|pages=1084–8|doi=10.1126/science.1259215|pmid=25430763|last12=Ren|first17=H. J.|last21=Huang|first20=W. J.|last20=Lucas|first19=Z|last19=Zhang|first18=X|last18=Qi|last17=Bouwmeester|first12=J|first16=K|last16=Yasukawa|first15=Y|last15=Wang|first14=S|last14=Zhang|first13=X|last13=Gu|first21=S|bibcode=2014Sci...346.1084S|s2cid=206561241}}</ref> | |||

| == Varieties == | == Varieties == | ||

| {{See also|List of cucumber varieties}} | |||

| ], ].]] | |||

| ] | |||

| In general ], cucumbers are classified into three main ] groups: slicing, ], and ]. | |||

| == Culinary uses == | |||

| *English cucumbers can grow as long as {{convert|2|ft|m}}. They are nearly seedless, have a delicate skin which is pleasant to eat, and are sometimes marketed as “Burpless”, because the seeds and skin of other varieties of cucumbers can give some people gas{{Citation needed|date=June 2008}}. | |||

| {{Cookbook|Cucumber}} | |||

| *East Asian cucumbers are mild, slender, deep green, and have a bumpy, ridged skin. They can be used for slicing, salads, pickling, etc., and are available year-round. | |||

| *Lebanese cucumbers are small, smooth-skinned and mild. Like the English cucumber, Lebanese cucumbers are nearly seedless. | |||

| *']s' (also known as yard long) has very long ribbed fruit with a thin skin that does not require peeling, but are actually an immature melon. This is the variety sold in middle-eastern markets as "pickled wild cucumber".<ref> Wild cucumbers got you in a pickle?</ref> In ], the term “wild cucumber” refers to ]. | |||

| *Persian Cucumber, better known as Mini seedless cucumbers, available from Canada during the summer, and all year-round from the Dominican. Increasing its popularity 30 to 40% a year. Easy to cut on average 5-8 in. long. | |||

| *Beit Alpha cucumbers are small, sweet cucumbers adapted to the dry climate of the Middle East | |||

| *Pickling cucumbers - Although any cucumber can be pickled, commercial pickles are made from cucumbers specially bred for uniformity of length-to-diameter ratio and lack of voids in the flesh. | |||

| *Slicers grown commercially for the North American market are generally longer, smoother, more uniform in color, and have a much tougher skin. Slicers in other countries are smaller and have a thinner, more delicate skin. | |||

| *''Dosakai'' is a yellow cucumber available in parts of ]. These fruits are generally spherical in shape. It is commonly cooked as curry, added in ]/Soup, ] and also in making Dosa-] (]) and ]. | |||

| *''Kekiri'' is a smooth skinned cucumber relatively hard and not used for salads. It is cooked as spicy curry. It is found in dry zone of Sri Lanka. It becomes orange colored when the fruit is matured. | |||

| *In May 2008, ] supermarket chain ] unveiled the 'c-thru- cumber', a thin-skinned variety which reportedly does not require peeling.<ref> - The 'c-thru' cucumbers with no skin to encumber them</ref> | |||

| == |

=== Fruit === | ||

| ==== Slicing ==== | |||

| Cucumbers originated in India.<ref>cucumber, Encyclopaedia Britannica Incorporated, 2008.</ref><ref name=Doijode/> Large genetic variety of cucumber has been observed in different parts of India.<ref name=Doijode>Doijode 2001: 281</ref> It has been cultivated for at least 3,000 years in Western ], and was probably introduced to other parts of Europe by the Romans. Records of cucumber cultivation appear in ] in the 9th century, England in the 14th century, and in North America by the mid-16th century. | |||

| Cucumbers grown to eat fresh are called ''slicing cucumbers''. The main varieties of slicers mature on ]s with large leaves that provide shading.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.almanac.com/plant/cucumbers|title=Cucumbers: Planting, growing, and harvesting cucumbers|publisher=Old Farmer's Almanac, Yankee Publishing, Inc., Dublin, NH|date=2016|access-date=11 August 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Slicers grown commercially for the North American market are generally longer, smoother, more uniform in color, and have much tougher skin. In contrast, those in other countries, often called ]s, are smaller and have thinner, more delicate skin, often with fewer seeds, thus are often sold in plastic skin for protection. This variety may also be called a ''telegraph cucumber'', particularly in ].<ref> Retrieved 18 May 2018</ref> | |||

| === Earliest cultivation === | |||

| Evidence indicates that the cucumber has been cultivated in Western Asia for 3,000 years. The cucumber is also listed among the foods of ancient ] and the legend of ] describes people eating cucumbers. Some sources also state that it was produced in ancient ], and it is certainly part of modern cuisine in ] and ], parts of which make up that ancient state. From India, it spread to ] (where it was called “σίκυον”, ''síkyon'') and ] (where the ] were especially fond of the crop), and later into ]. | |||

| ==== Pickling ==== | |||

| According to Pliny the Elder (The Natural History, Book XIX, Chapter 23), the Ancient Greeks grew cucumbers, and there were different varieties in Italy, Africa, and modern-day Serbia. | |||

| {{Main|Pickled cucumber}} | |||

| ]'' pickled cucumbers sold as ] on ] island]] | |||

| ] with ], sugar, ], and spices creates various flavored products from cucumbers and other foods.<ref name="avi">{{cite web|author1=Avi, Torey|title=History in a jar: The story of pickles|url=http://www.pbs.org/food/the-history-kitchen/history-pickles/|publisher=Public Broadcasting Service|access-date=13 November 2017|date=3 September 2014}}</ref> Although any cucumber can be pickled, commercial pickles are made from cucumbers specially bred for uniformity of length-to-diameter ratio and lack of voids in the flesh. Those cucumbers intended for pickling, called ''picklers'', grow to about {{convert|7|to|10|cm|in|abbr=on|0}} long and {{convert|2.5|cm|in|abbr=on|0}} wide. Compared to slicers, picklers tend to be shorter, thicker, less-regularly shaped, and have bumpy skin with tiny white or black-dotted spines. Color can vary from creamy yellow to pale or dark green.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} | |||

| ==== Gherkin ==== | |||

| ], also called ''cornichons'',<ref name="kitchn">{{cite web|title=What's The Deal With Cornichons?|url=http://www.thekitchn.com/whats-the-deal-with-cornichons-117240|publisher=The Kitchn|access-date=13 November 2017|date=2017}}</ref> or ''baby pickles'', are small cucumbers, typically those {{convert|1|to|5|in|cm|round=0.5|order=flip}} in length, often with bumpy skin, which are typically used for pickling.<ref name="zon">{{cite web|title=Gherkins|url=http://www.royalzon.com/en/consumer/fruit-vegetables/gherkins|publisher=Zon|access-date=13 November 2017|location=Venlo, Netherlands|date=2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171114040538/http://www.royalzon.com/en/consumer/fruit-vegetables/gherkins|archive-date=14 November 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="wifss">{{cite web|title=Cucumbers|url=http://www.wifss.ucdavis.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/FDA_WIFSS_-Cucumbers_PDF.pdf|publisher=Western Institute for Food Safety and Security, US Department of Agriculture|access-date=13 November 2017|location=University of California-Davis|date=May 2016}}</ref><ref name="india">{{cite web|title=Cucumbers and gherkins|url=http://apeda.gov.in/apedawebsite/SubHead_Products/Cucumber_and_Gherkins.htm|publisher=Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority, Government of India|access-date=13 November 2017|date=2015}}</ref> The word ''gherkin'' comes from the early modern ] ''gurken'' or ''augurken'' ('small pickled cucumber').<ref>{{cite dictionary|title=Word origin and history for gherkin|url=http://www.dictionary.com/browse/gherkin|dictionary=Dictionary.com|access-date=13 November 2017|date=2017}}</ref> The term is also used in the name for '']'', the ''West Indian gherkin'', a closely related species.<ref>{{cite web|title=West Indian gherkin, ''Cucumis anguria'' L.|url=http://pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Cucumis+anguria|publisher=Plants for a Future|access-date=13 November 2017|date=2012}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Burpless ==== | |||

| Burpless cucumbers are sweeter and have a thinner skin than other varieties of cucumber. They are reputed to be easy to digest and to have a pleasant taste. They can grow as long as {{convert|2|ft|cm|sp=us|order=flip|-1}}, are nearly seedless, and have a delicate skin. Most commonly grown in greenhouses, these ] cucumbers are often found in ], ] in plastic. They are marketed as either burpless or seedless, as the seeds and skin of other varieties of cucumbers are said to give some people gas.<ref>{{cite web|last=Jordan-Reilly|first=Melissa|title=Why do cucumbers upset my digestion?|url=http://www.livestrong.com/article/471722-why-do-cucumbers-upset-my-digestion/|publisher=LiveStrong.com|date=15 September 2013 }}</ref> | |||

| === Shoots === | |||

| Cucumber ] are regularly consumed as a vegetable, especially in rural areas. In Thailand they are often served with a crab meat sauce. They can also be stir fried or used in soups.<ref name= "Cook's Guide" >{{cite book |last1=Hutton |first1=Wendy |title=A Cook's Guide to Asian Vegetables |date=2004 |publisher=Periplus Editions |location=Singapore |isbn=0794600786 |pages=42–43}}</ref> | |||

| ==Production== | |||

| {| class="wikitable floatright" style="clear:right; width:13em; text-align:center; margin-right:1em;" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! colspan=2|Cucumber production – 2022 | |||

| |- | |||

| ! style="background:#ddf;"| Country | |||

| ! style="background:#ddf;"| {{small|millions<br /> of ]s}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{CHN}} || 77.3 | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{TUR}} || 1.9 | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{RUS}} || 1.6 | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{MEX}} || 1.1 | |||

| |- | |||

| | '''World''' || '''94.7''' | |||

| |- | |||

| |colspan=2|<small>Source: ] of the ]</small><ref name="faostat">{{cite web|url=http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC|title= Cucumber and gherkin production in 2022, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity/Year (pick lists)|date=2024|publisher=UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT)|access-date=10 June 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |} | |||

| In 2022, world production of cucumbers and gherkins was 95 million ]s, led by China with 82% of the total.<ref name=faostat/> | |||

| == Cultivation history == | |||

| Cultivated for at least 3,000 years, the cultivated cucumbers ''"Cucumis sativus"'' were domesticated in ] from wild "''C. sativus var. hardwickii''".<ref name="nph.onlinelibrary.wiley.com"/><ref name="Plant Breeding Reviews"/><ref name="tandfonline.com"/> where a great many varieties have been observed, along with its closest living relative, '']''.<ref>]. 21 July 2010. "." ''NewsTrack India.'' Retrieved on 4 June 2020.</ref> Three main cultivar groups of cucumber are namely Eurasian cucumbers (slicing cucumbers eaten raw and immature), East Asian cucumbers (pickling cucumbers) and Xishuangbanna cucumbers. Based on demographic modelling, the East Asian C. sativus cultivars diverged from the Indian cultivars c. 2500 years ago.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Chomicki |first1=Guillaume |last2=Schaefer |first2=Hanno |last3=Renner |first3=Susanne S. |title=Origin and domestication of Cucurbitaceae crops: insights from phylogenies, genomics and archaeology |journal=New Phytologist |date=June 2020 |volume=226 |issue=5 |pages=1240–1255 |doi=10.1111/nph.16015 |language=en |issn=0028-646X|doi-access=free |bibcode=2020NewPh.226.1240C }}</ref> It was probably introduced to Europe by the ] or ]. Records of cucumber cultivation appear in ] in the 9th century, ] in the 14th century, and in North America by the mid-16th century.<ref name="Encyclopedia Britannica" /><ref name="Renner 2007">{{cite journal|last1=Renner|first1=SS|last2=Schaefer|first2=H|last3=Kocyan|first3=A|year=2007|title=Phylogenetics of ''Cucumis'' (Cucurbitaceae): Cucumber (''C. sativus'') belongs in an Asian/Australian clade far from melon (''C. melo'')|journal=BMC Evolutionary Biology|volume=7|issue=1 |page=58|doi=10.1186/1471-2148-7-58|pmc=3225884|pmid=17425784 |doi-access=free |bibcode=2007BMCEE...7...58R }} | |||

| </ref><ref name="Doijode">Doijode, S. D. 2001. ''Seed storage of horticultural crops''. ]. {{ISBN|1-56022-901-2}}. p. 281.</ref><ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.21273/HORTSCI.41.3.571|title=Taxonomic Relationships of A Rare ''Cucumis'' Species (''C. hystrix'' Chakr.) and Its Interspecific Hybrid with Cucumber|year=2006|last1=Zhuang|first1=Fei-Yun|last2=Chen|first2=Jin-Feng|last3=Staub|first3=Jack E.|last4=Qian|first4=Chun-Tao|journal=HortScience|volume=41|issue=3|pages=571–574|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| === Roman Empire === | === Roman Empire === | ||

| According to ], the Emperor ] had the cucumber on his table daily during summer and winter. In order to have it available for his table every day of the year, the Romans reportedly used artificial methods of growing (similar to the ]), whereby ''mirrorstone'' refers to Pliny's ''lapis specularis'', believed to have been sheet ]:<ref name="AncientInventions">{{cite book|author1=James, Peter J. |author2=Thorpe, Nick |author3=Thorpe, I. J. |title=Ancient Inventions|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VmJLd3sSYecC|year=1995|publisher=Ballantine Books|isbn=978-0-345-40102-1|chapter=Ch. 12, Sport and Leusure: Roman Gardening Technology|page=563}}</ref><ref>]. 1855. " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200605044058/http://perseus.uchicago.edu/perseus-cgi/citequery3.pl?dbname=LatinAugust2012&getid=1&query=Plin.%20Nat.%2019.23 |date=5 June 2020 }}." Ch. 23 in '']'' XIX, translated by ] and ]. London: ]. – via ''Perseus under PhiloLogic'', also via Perseus Project.</ref> | |||

| According to The Natural History of Pliny, by Pliny the Elder (Book XIX, Chapter 23), the ] Emperor ] had the cucumber on his table daily during summer and winter. The Romans reportedly used artificial methods (similar to the greenhouse system) of growing to have it available for his table every day of the year. To quote Pliny; "Indeed, he was never without it; for he had raised beds made in frames upon wheels, by means of which the cucumbers were moved and exposed to the full heat of the sun; while, in winter, they were withdrawn, and placed under the protection of frames glazed with mirrorstone. Reportedly, they were also cultivated in cucumber houses glazed with oiled cloth known as “]”. | |||

| {{Blockquote|text=Indeed, he was never without it; for he had raised beds made in frames upon wheels, by means of which the cucumbers were moved and exposed to the full heat of the sun; while, in winter, they were withdrawn, and placed under the protection of frames glazed with mirrorstone.|author=Pliny the Elder|title='']'' XIX.xxiii|source="Vegetables of a Cartilaginous Nature—Cucumbers. Pepones"}} | |||

| Pliny the Elder describes the Italian fruit as very small, probably like a ], describing it as a wild cucumber considerably smaller than the cultivated one. Pliny also describes the preparation of a medication known as “elaterium”, though some scholars believe that he refers to ''Cucumis silvestris asininus'', a species different from the common cucumber.<ref>Pliny the Elder, Book XX. Remedies Derived from the Garden Plants Chapter 2. (1.) -- The Wild Cucumber; Twenty-Six Remedies.</ref> Pliny also writes about several other varieties of cucumber, including the Cultivated Cucumber,<ref>Pliny the Elder, Book XX, chap. 5, the "Anguine or Erratic Cucumber" (Book XX, Chap 4. (2.))</ref> and remedies from the different types (9 from the cultivated, 5 from the "anguine", and 26 from the "wild"). The Romans are reported to have used cucumbers to treat scorpion bites, bad eyesight, and to scare away mice. Wives wishing for children wore them around their waists. They were also carried by the midwives, and thrown away when the child was born. | |||

| Reportedly, they were also cultivated in ''specularia'', cucumber houses glazed with oiled cloth.<ref name="AncientInventions" /> Pliny describes the Italian fruit as very small, probably like a ]. He also describes the preparation of a medication known as ''elaterium''. However, some scholars{{who|date=February 2013}} believe that he was instead referring to '']'', known in pre-] times as ''Cucumis silvestris'' or ''Cucumis asininus'' ('wild cucumber' or 'donkey cucumber'), a species different from the common cucumber.<ref>], '']'' XX. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200605043843/http://perseus.uchicago.edu/perseus-cgi/citequery3.pl?dbname=LatinAugust2012&getid=1&query=Plin.%20Nat.%2020.3 |date=5 June 2020 }}.</ref> Pliny also writes about several other varieties of cucumber, including the cultivated cucumber,<ref>], '']'' XX. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200605043845/http://perseus.uchicago.edu/perseus-cgi/citequery3.pl?dbname=LatinAugust2012&getid=1&query=Plin.%20Nat.%2020.4 |date=5 June 2020 }}– {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200605043846/http://perseus.uchicago.edu/perseus-cgi/citequery3.pl?dbname=LatinAugust2012&getid=1&query=Plin.%20Nat.%2020.5 |date=5 June 2020 }}.</ref> and remedies from the different types (9 from the cultivated; 5 from the "anguine;" and 26 from the "wild"). | |||

| === Middle Ages === | === Middle Ages === | ||

| Charlemagne had cucumbers grown in his gardens in |

] had cucumbers grown in his gardens in the 8th/9th century. They were reportedly introduced into England in the early 14th century, lost, then reintroduced approximately 250 years later. The ] (through the ] ]) brought cucumbers to ] in 1494. In 1535, ], a French explorer, found "very great cucumbers" grown on the site of what is now ].{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} | ||

| The ] (in the person of ]) brought cucumbers to ] in 1494. In 1535, ], a French explorer, found “very great cucumbers” grown on the site of what is now ]. | |||

| === |

=== Early-modern age === | ||

| ], or ''cucumber aldehyde'', is a component of the distinctive aroma of cucumbers.|alt=trans,cis-2,6-Nonadienal, or cucumber aldehyde|250px]] | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=June 2008}} | |||

| Throughout the |

Throughout the 16th century, European trappers, traders, ] hunters, and explorers bartered for the products of American Indian ]. The tribes of the ] and the ] learned from the Spanish how to grow European crops. The farmers on the Great Plains included the ] and ]. They obtained cucumbers and ]s from the Spanish, and added them to the crops they were already growing, including several varieties of ] and ]s, ]s, ], and ] plants.<ref>{{cite book|title=Taste, Memory: Forgotten Foods, Lost Flavors, and why They Matter|pages=109|last=Buchanan|first=David|publisher=Chelsea Green Publishing|location=VT, USA|isbn=9781603584401|year=2012}}</ref> The ] were also growing them when the first Europeans visited them.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Kuhnlein |first1=H. V. |author-link=Harriet V. Kuhnlein |title=Traditional Plant Foods of Canadian Indigenous Peoples: Nutrition, Botany and Use |last2=Turner |first2=N. J. |publisher=Gordon and Breach |year=1996 |isbn=9782881244650 |location=Amsterdam, Netherlands |pages=159}}</ref> | ||

| In 1630, the Reverend ] produced a book called |

In 1630, the Reverend ] produced a book called ''New-Englands Plantation'' in which, describing a garden on Conant's Island in ] known as ''The Governor's Garden'', he states:<ref>]. 1906. '']''. Salem, MA: Essex Book and Print Club. {{OCLC|1049892552}}. .</ref><blockquote>The countrie aboundeth naturally with store of roots of great {{Sic|varietie}} and good to eat. Our turnips, parsnips, and carrots are here both bigger and sweeter than is ordinary to be found in England. Here are store of pompions, cowcumbers, and other things of that nature which I know not...</blockquote>In ''New England Prospect'' (1633, England), William Wood published observations he made in 1629 in America:<ref>Wood, William. (1634). "", pp. 13–18 in ''New England Prospect''. London.</ref><blockquote>{{Sic|The ground affords very good kitchin gardens, for Turneps, Parsnips, Carrots, Radishes, and Pompions, Muskmillons, Isquoter-squashes, coucumbars, Onyons, and whatever grows well in England grows as well there, many things being better and larger.}}</blockquote> | ||

| ===Age of Enlightenment and later=== | |||

| William Wood also published in 1633’s New England Prospect (published in England) observations he made in 1629 in America: “The ground affords very good kitchin gardens, for Turneps, Parsnips, Carrots, Radishes, and Pompions, Muskmillons, Isquoter-squashes, coucumbars, Onyons, and whatever grows well in England grows as well there, many things being better and larger.” | |||

| ] (watercolour, 1826 or 1827)]] | |||

| In the later 1600s, a prejudice developed against uncooked vegetables and fruits. A number of articles in contemporary health publications state that uncooked plants brought on summer diseases and should be forbidden to children. The cucumber kept this vile reputation for an inordinate period of time: “fit only for consumption by cows”, which some believe is why it gained the name, “cowcumber”. | |||

| In the later 17th century, a prejudice developed against uncooked vegetables and fruits. A number of articles in contemporary health publications stated that uncooked plants brought on summer diseases and should be forbidden to children. The cucumber kept this reputation for an inordinate period of time, "fit only for consumption by cows," which some believe is why it gained the name, ''cowcumber''.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} | |||

| A copper etching made by Maddalena Bouchard between 1772 and 1793 shows this plant to have smaller, almost bean-shaped fruits, and small yellow flowers. The small form of the cucumber is figured in Herbals of the sixteenth century, but states, ‘if hung in a tube while in blossom, the Cucumber will grow to a most surprising length.’ | |||

| ] wrote in his diary on |

] wrote in his diary on 22 August 1663:<ref>. Pepysdiary.com. Retrieved on 25 November 2012.</ref><blockquote>his day Sir W. Batten tells me that Mr. Newburne is dead of eating cowcumbers, of which the other day I heard of another, I think.</blockquote> | ||

| John Evelyn in 1699 wrote that the cucumber, 'however dress'd, was thought fit to be thrown away, being accounted little better than poyson (poison)'.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Evelyn |first=John |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CiXbAAAAMAAJ |title=Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets |date=1699 |publisher=Prospect Books |isbn=978-0-907325-12-3 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Davidson |first=Jan |title=Pickles: A Global History (Edible) |date=2018-07-15 |publisher=Reaktion Books |isbn=9781780239194}}</ref> | |||

| ], in his travels in ], ], ] and ] in the 1700s, came across the Egyptian or hairy cucumber, ''Cucumis chate''. It is said by Hasselquist to be the “queen of cucumbers, refreshing, sweet, solid, and wholesome.” He also states that “they still form a great part of the food of the lower-class people in Egypt serving them for meat, drink and physic.” George E. Post, in ], states, “It is longer and more slender than the common cucumber, being often more than a foot long, and sometimes less than an inch thick, and pointed at both ends.” | |||

| According to 18th-century British writer ], it was commonly said among English physicians that a cucumber "should be well sliced, and dressed with pepper and vinegar, and then thrown out, as good for nothing."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Boswell |first1=James |title=The Life of Samuel Johnson: Including A Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides, Volumen 1 |date=1832 |publisher=Carter, Hendee and Company |page=423 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fKAEAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA423 |access-date=29 March 2024}}</ref> | |||

| == Industry == | |||

| ] output in 2005]]According to FAO, China produced at least 60% of the global output of cucumber and gherkin in 2005, followed at a distance by Turkey, Russia, Iran and the United States.{{Facts|date=June 2009}} | |||

| A copper ] made by Maddalena Bouchard between 1772 and 1793 shows this plant to have smaller, almost bean-shaped fruits, and small yellow flowers. The small form of the cucumber is figured in ]s of the 16th century, however stating that "f hung in a tube while in blossom, the Cucumber will grow to a most surprising length."{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} | |||

| === Cultivation studies === | |||

| The usual commercial method of cultivating cucumbers involves the use of mineral (manufactured) ]. | |||

| == |

==Gallery== | ||

| <gallery mode="packed"> | |||

| ===Notes=== | |||

| File:Organic Gardener Holding a Fresh Salad Cucumber.jpg|Salad cucumber | |||

| {{refs|2}} | |||

| File:An Indian yellow cucumber.jpg|An Indian yellow cucumber | |||

| ===Reference sources=== | |||

| File:Kurkkuja.jpg|A Scandinavian cucumber in slices | |||

| {| valign=top style="font-size:95%;"|- | |||

| File:Cucumber grated.jpg|Grated cucumber | |||

| |width=200 valign=top| | |||

| File:Komkommer (Cucumis sativus 'Gele Tros').jpg|Komkommer (''Cucumis sativus'' 'Gele Tros') | |||

| * | |||

| File:Hmong cucumber.jpg|A varietal grown by the ] with textured skin and large seeds | |||

| * | |||

| File:Lemon cucumber J1.JPG|Lemon cucumber | |||

| * | |||

| File:Mizeria.jpg|Dish with cucumber cut pieces (]) | |||

| * | |||

| File:PicklingCucumbers.jpg|Pickling cucumbers | |||

| * | |||

| File:Spreewaldgurke2.jpg|Gherkins | |||

| |width=200 valign=top| | |||

| File:Persiancucumber.jpg|] burpless cucumber, ] | |||

| * Doijode, S. D. (2001). ''Seed storage of horticultural crops''. Haworth Press. ISBN 1-56022-901-2 | |||

| File:Leaves of Cucumber (a creeping vine plant).jpg|Leaves | |||

| * The Complete Cucumber by Caroline Francis | |||

| File:Cucumber vine in New Jersey.jpg|A ] emerges from cucumber vines to facilitate climbing | |||

| * Cucumbers by Bob Adams Publishers | |||

| File:Cucumbers growing on a string lattice structure.jpg|A string ] supports vine growth | |||

| |width=200 valign=top| | |||

| File:Cucumber hanging on the vine.JPG|A ]-shaped cucumber hanging on the ] | |||

| * Selected Themes and Icons from Medieval Spanish Literature: of Berards, Shoes, Cucumbers and Leprosy by John R. Burt | |||

| File:Cucumber plants.jpg|Cucumber plant | |||

| |width=200 valign=top| | |||

| File:Harvested vegetables(Cucumbers).jpg|Harvested Cucumber among other vegetables | |||

| * Origin of Cultivated Plants by Alphonse de Candolle | |||

| File:Harvested vegetables(Tomatoes, Cucumbers and Aubergine) 2.jpg|Harvested cucumber among other vegetables | |||

| * The Natural History of Pliny (Book XX primarily, with a reference to Tiberius eating them in Book XIX, Chapter 23) | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| * Bioresource Technology, Volume 98, Issue 1, January 2007, Pages 214-217 | |||

| |} | |||

| == |

== See also == | ||

| {{Div col|colwidth=22em}} | |||

| {{Commons}} | |||

| * ], a variety of ] that resembles a cucumber | |||

| * {{ITIS|taxon = Cucumis sativus|ID = 22364|date = January 30|year = 2006}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * - shows classification and distribution by US state. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * by Thomas Watkins | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ], named for its resemblance to the fruit | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| == References == | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Reflist|35em}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Taxonbar|from=Q23425}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 14:48, 8 December 2024

Species of flowering plant that produces cucumbers For other uses, see Cucumber (disambiguation).

| Cucumber | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cucumbers growing on vines | |

| |

| A single cucumber fruit | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Cucurbitales |

| Family: | Cucurbitaceae |

| Genus: | Cucumis |

| Species: | C. sativus |

| Binomial name | |

| Cucumis sativus L. | |

The cucumber (Cucumis sativus) is a widely-cultivated creeping vine plant in the family Cucurbitaceae that bears cylindrical to spherical fruits, which are used as culinary vegetables. Considered an annual plant, there are three main types of cucumber—slicing, pickling, and seedless—within which several cultivars have been created. The cucumber originates in Asia extending from India, Nepal, Bangladesh, China (Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi), and Northern Thailand, but now grows on most continents, and many different types of cucumber are grown commercially and traded on the global market. In North America, the term wild cucumber refers to plants in the genera Echinocystis and Marah, though the two are not closely related.

Description

The cucumber is a creeping vine that roots in the ground and grows up trellises or other supporting frames, wrapping around supports with thin, spiraling tendrils. The plant may also root in a soilless medium, whereby it will sprawl along the ground in lieu of a supporting structure. The vine has large leaves that form a canopy over the fruits.

The fruit of typical cultivars of cucumber is roughly cylindrical, but elongated with tapered ends, and may be as large as 62 centimeters (24 in) long and 10 centimeters (4 in) in diameter.

Cucumber fruits consist of 95% water (see nutrition table). In botanical terms, the cucumber is classified as a pepo, a type of botanical berry with a hard outer rind and no internal divisions. However, much like tomatoes and squashes, it is often perceived, prepared, and eaten as a vegetable.

Flowering and pollination

| NCBI genome ID | 1639 |

|---|---|

| Ploidy | diploid |

| Genome size | 323.99 Mb |

| Sequenced organelle | mitochondrion |

| Organelle size | 244.82 Mb |

| Year of completion | 2011 |

Most cucumber cultivars are seeded and require pollination. For this purpose, thousands of honey beehives are annually carried to cucumber fields just before bloom. Cucumbers may also be pollinated via bumblebees and several other bee species. Most cucumbers that require pollination are self-incompatible, thus requiring the pollen of another plant in order to form seeds and fruit. Some self-compatible cultivars exist that are related to the 'Lemon cucumber' cultivar.

A few cultivars of cucumber are parthenocarpic, the blossoms of which create seedless fruit without pollination, which degrades the eating quality of these cultivar. In the United States, these are usually grown in greenhouses, where bees are excluded. In Europe, they are grown outdoors in some regions, where bees are likewise excluded.

Traditional cultivars produce male blossoms first, then female, in about equivalent numbers. Newer gynoecious hybrid cultivars produce almost all female blossoms. They may have a pollenizer cultivar interplanted, and the number of beehives per unit area is increased, but temperature changes induce male flowers even on these plants, which may be sufficient for pollination to occur.

In 2009, an international team of researchers announced they had sequenced the cucumber genome.

A study of genetic recombination during meiosis in cucumber provided a high resolution landscape of meiotic DNA double strand-breaks and genetic crossovers. The average number of crossovers per chromosome per meiosis was 0.92 to 0.99.

Herbivore defense

Phytochemicals in cucumbers may discourage natural foraging by herbivores, such as insects, nematodes or wildlife. As a possible defense mechanism, cucumbers produce cucurbitacin C, which causes a bitter taste in some cucumber varieties. This potential mechanism is under preliminary research to identify whether cucumbers are able to deter herbivores and environmental stresses by using an intrinsic chemical defense, particularly in the leaves, cotyledons, pedicel, carpopodium, and fruit.

Nutrition, aroma, and taste

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 65 kJ (16 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carbohydrates | 3.63 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 1.67 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 0.5 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fat | 0.11 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Protein | 0.65 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 95.23 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Link to USDA database entry | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults, except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Raw cucumber (with peel) is 95% water, 4% carbohydrates, 1% protein, and contains negligible fat. A 100-gram (3+1⁄2-ounce) reference serving provides 65 kilojoules (16 kilocalories) of food energy. It has a low content of micronutrients: it is notable only for vitamin K, at 14% of the Daily Value (table).

Depending on variety, cucumbers may have a mild melon aroma and flavor, in part resulting from unsaturated aldehydes, such as (E,Z)-nona-2,6-dienal, and the cis- and trans- isomers of 2-nonenal. The slightly bitter taste of cucumber rind results from cucurbitacins.

Varieties

See also: List of cucumber varieties

In general cultivation, cucumbers are classified into three main cultivar groups: slicing, pickled, and seedless/burpless.

Culinary uses

Fruit

Slicing

Cucumbers grown to eat fresh are called slicing cucumbers. The main varieties of slicers mature on vines with large leaves that provide shading.

Slicers grown commercially for the North American market are generally longer, smoother, more uniform in color, and have much tougher skin. In contrast, those in other countries, often called European cucumbers, are smaller and have thinner, more delicate skin, often with fewer seeds, thus are often sold in plastic skin for protection. This variety may also be called a telegraph cucumber, particularly in Australasia.

Pickling

Main article: Pickled cucumber

Pickling with brine, sugar, vinegar, and spices creates various flavored products from cucumbers and other foods. Although any cucumber can be pickled, commercial pickles are made from cucumbers specially bred for uniformity of length-to-diameter ratio and lack of voids in the flesh. Those cucumbers intended for pickling, called picklers, grow to about 7 to 10 cm (3 to 4 in) long and 2.5 cm (1 in) wide. Compared to slicers, picklers tend to be shorter, thicker, less-regularly shaped, and have bumpy skin with tiny white or black-dotted spines. Color can vary from creamy yellow to pale or dark green.

Gherkin

Gherkins, also called cornichons, or baby pickles, are small cucumbers, typically those 2.5 to 12.5 centimetres (1 to 5 in) in length, often with bumpy skin, which are typically used for pickling. The word gherkin comes from the early modern Dutch gurken or augurken ('small pickled cucumber'). The term is also used in the name for Cucumis anguria, the West Indian gherkin, a closely related species.

Burpless

Burpless cucumbers are sweeter and have a thinner skin than other varieties of cucumber. They are reputed to be easy to digest and to have a pleasant taste. They can grow as long as 60 centimeters (2 ft), are nearly seedless, and have a delicate skin. Most commonly grown in greenhouses, these parthenocarpic cucumbers are often found in grocery markets, shrink-wrapped in plastic. They are marketed as either burpless or seedless, as the seeds and skin of other varieties of cucumbers are said to give some people gas.

Shoots

Cucumber shoots are regularly consumed as a vegetable, especially in rural areas. In Thailand they are often served with a crab meat sauce. They can also be stir fried or used in soups.

Production

| Cucumber production – 2022 | |

|---|---|

| Country | millions of tonnes |

| 77.3 | |

| 1.9 | |

| 1.6 | |

| 1.1 | |

| World | 94.7 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations | |

In 2022, world production of cucumbers and gherkins was 95 million tonnes, led by China with 82% of the total.

Cultivation history

Cultivated for at least 3,000 years, the cultivated cucumbers "Cucumis sativus" were domesticated in India from wild "C. sativus var. hardwickii". where a great many varieties have been observed, along with its closest living relative, Cucumis hystrix. Three main cultivar groups of cucumber are namely Eurasian cucumbers (slicing cucumbers eaten raw and immature), East Asian cucumbers (pickling cucumbers) and Xishuangbanna cucumbers. Based on demographic modelling, the East Asian C. sativus cultivars diverged from the Indian cultivars c. 2500 years ago. It was probably introduced to Europe by the Greeks or Romans. Records of cucumber cultivation appear in France in the 9th century, England in the 14th century, and in North America by the mid-16th century.

Roman Empire

According to Pliny the Elder, the Emperor Tiberius had the cucumber on his table daily during summer and winter. In order to have it available for his table every day of the year, the Romans reportedly used artificial methods of growing (similar to the greenhouse system), whereby mirrorstone refers to Pliny's lapis specularis, believed to have been sheet mica:

Indeed, he was never without it; for he had raised beds made in frames upon wheels, by means of which the cucumbers were moved and exposed to the full heat of the sun; while, in winter, they were withdrawn, and placed under the protection of frames glazed with mirrorstone.

— Pliny the Elder, Natural History XIX.xxiii, "Vegetables of a Cartilaginous Nature—Cucumbers. Pepones"

Reportedly, they were also cultivated in specularia, cucumber houses glazed with oiled cloth. Pliny describes the Italian fruit as very small, probably like a gherkin. He also describes the preparation of a medication known as elaterium. However, some scholars believe that he was instead referring to Ecballium elaterium, known in pre-Linnean times as Cucumis silvestris or Cucumis asininus ('wild cucumber' or 'donkey cucumber'), a species different from the common cucumber. Pliny also writes about several other varieties of cucumber, including the cultivated cucumber, and remedies from the different types (9 from the cultivated; 5 from the "anguine;" and 26 from the "wild").

Middle Ages

Charlemagne had cucumbers grown in his gardens in the 8th/9th century. They were reportedly introduced into England in the early 14th century, lost, then reintroduced approximately 250 years later. The Spaniards (through the Italian Christopher Columbus) brought cucumbers to Haiti in 1494. In 1535, Jacques Cartier, a French explorer, found "very great cucumbers" grown on the site of what is now Montreal.

Early-modern age

Throughout the 16th century, European trappers, traders, bison hunters, and explorers bartered for the products of American Indian agriculture. The tribes of the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains learned from the Spanish how to grow European crops. The farmers on the Great Plains included the Mandan and Abenaki. They obtained cucumbers and watermelons from the Spanish, and added them to the crops they were already growing, including several varieties of corn and beans, pumpkins, squash, and gourd plants. The Iroquois were also growing them when the first Europeans visited them.

In 1630, the Reverend Francis Higginson produced a book called New-Englands Plantation in which, describing a garden on Conant's Island in Boston Harbor known as The Governor's Garden, he states:

The countrie aboundeth naturally with store of roots of great varietie [sic] and good to eat. Our turnips, parsnips, and carrots are here both bigger and sweeter than is ordinary to be found in England. Here are store of pompions, cowcumbers, and other things of that nature which I know not...

In New England Prospect (1633, England), William Wood published observations he made in 1629 in America:

The ground affords very good kitchin gardens, for Turneps, Parsnips, Carrots, Radishes, and Pompions, Muskmillons, Isquoter-squashes, coucumbars, Onyons, and whatever grows well in England grows as well there, many things being better and larger. [sic]

Age of Enlightenment and later

In the later 17th century, a prejudice developed against uncooked vegetables and fruits. A number of articles in contemporary health publications stated that uncooked plants brought on summer diseases and should be forbidden to children. The cucumber kept this reputation for an inordinate period of time, "fit only for consumption by cows," which some believe is why it gained the name, cowcumber.

Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary on 22 August 1663:

his day Sir W. Batten tells me that Mr. Newburne is dead of eating cowcumbers, of which the other day I heard of another, I think.

John Evelyn in 1699 wrote that the cucumber, 'however dress'd, was thought fit to be thrown away, being accounted little better than poyson (poison)'.

According to 18th-century British writer Samuel Johnson, it was commonly said among English physicians that a cucumber "should be well sliced, and dressed with pepper and vinegar, and then thrown out, as good for nothing."

A copper etching made by Maddalena Bouchard between 1772 and 1793 shows this plant to have smaller, almost bean-shaped fruits, and small yellow flowers. The small form of the cucumber is figured in Herbals of the 16th century, however stating that "f hung in a tube while in blossom, the Cucumber will grow to a most surprising length."

Gallery

-

Salad cucumber

Salad cucumber

-

An Indian yellow cucumber

An Indian yellow cucumber

-

A Scandinavian cucumber in slices

A Scandinavian cucumber in slices

-

Grated cucumber

Grated cucumber

-

Komkommer (Cucumis sativus 'Gele Tros')

Komkommer (Cucumis sativus 'Gele Tros')

-

A varietal grown by the Hmong people with textured skin and large seeds

A varietal grown by the Hmong people with textured skin and large seeds

-

Lemon cucumber

-

Dish with cucumber cut pieces (mizeria)

Dish with cucumber cut pieces (mizeria)

-

Pickling cucumbers

Pickling cucumbers

-

Gherkins

Gherkins

-

Isfahan burpless cucumber, Iran

Isfahan burpless cucumber, Iran

-

Leaves

Leaves

-

A tendril emerges from cucumber vines to facilitate climbing

A tendril emerges from cucumber vines to facilitate climbing

-

A string lattice supports vine growth

A string lattice supports vine growth

-

A bulb-shaped cucumber hanging on the vine

-

Cucumber plant

Cucumber plant

-

Harvested Cucumber among other vegetables

Harvested Cucumber among other vegetables

-

Harvested cucumber among other vegetables

Harvested cucumber among other vegetables

See also

- Armenian cucumber, a variety of melon that resembles a cucumber

- Cucumber blessing

- Cucumber cake

- Cucumber juice

- Cucumber raita

- Cucumber sandwich

- Cucumber soda

- Cucumber soup

- Sea cucumber, named for its resemblance to the fruit

References

- ^ "Cucumber." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2019.

- Silvertown, Jonathan (1985). "Survival, Fecundity and Growth of Wild Cucumber, Echinocystis Lobata". Journal of Ecology. 73 (3): 841–849. Bibcode:1985JEcol..73..841S. doi:10.2307/2260151. JSTOR 2260151.

- ^ Chomicki, Guillaume; Schaefer, Hanno; Renner, Susanne S. (June 2020). "Origin and domestication of Cucurbitaceae crops: insights from phylogenies, genomics and archaeology". New Phytologist. 226 (5): 1240–1255. Bibcode:2020NewPh.226.1240C. doi:10.1111/nph.16015. PMID 31230355.

- ^ Weng, Yiqun (7 January 2021). "Cucumis sativus Chromosome Evolution, Domestication, and Genetic Diversity: Implications for Cucumber Breeding". Plant Breeding Reviews. Wiley. pp. 79–111. doi:10.1002/9781119717003.ch4. ISBN 978-1-119-71700-3.

- "Cucumis sativus L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Bisht, I. S.; Bhat, K.V.; Tanwar, S. P. S.; Bhandari, D. C.; Joshi, Kamal; Sharma, A. K. (January 2004). "Distribution and genetic diversity of Cucumis sativus var. hardwickii (Royle) Alef in India". The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology. 79 (5): 783–791. Bibcode:2004JHSB...79..783B. doi:10.1080/14620316.2004.11511843. ISSN 1462-0316.

- Mariod, Abdalbasit Adam; Mirghani, Mohamed Elwathig Saeed; Hussein, Ismail Hassan (14 April 2017). Cucumis sativus, Cucumber; Chapter 16 in: Unconventional Oilseeds and Oil Sources. Academic Press. ISBN 9780128134337.

- Zhang, Tingting; Li, Xvzhen; Yang, Yuting; Guo, Xiao; Feng, Qin; Dong, Xiangyu; Chen, Shuxia (2019). "Genetic analysis and QTL mapping of fruit length and diameter in a cucumber (Cucumber sativus L.) recombinant inbred line (RIL) population". Scientia Horticulturae. 250: 214–222. Bibcode:2019ScHor.250..214Z. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2019.01.062. S2CID 92837522.

- "Cucumber". Fruit or Vegetable?. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ Nonnecke, I.L. (1989). Vegetable Production. Springer. ISBN 9780442267216.

- Huang, S.; Li, R.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; et al. (2009). "The genome of the cucumber, Cucumis sativus L". Nature Genetics. 41 (12): 1275–81. doi:10.1038/ng.475. PMID 19881527.

- ^ Wang Y, Dong Z, Ma Y, Zheng Y, Huang S, Yang X (October 2023). "Comprehensive dissection of meiotic DNA double-strand breaks and crossovers in cucumber". Plant Physiol. 193 (3): 1913–1932. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiad432. PMC 10602612. PMID 37530486.

- Shang Y, Ma Y, Zhou Y, et al. (November 2014). "Plant science. Biosynthesis, regulation, and domestication of bitterness in cucumber". Science. 346 (6213): 1084–8. Bibcode:2014Sci...346.1084S. doi:10.1126/science.1259215. PMID 25430763. S2CID 206561241.

- ^ Liu, Zhiqiang; Li, Yawen; Cao, Chunyu; Liang, Shan; Ma, Yongshuo; Liu, Xin; Pei, Yanxi (February 2019). "The role of H2S in low temperature-induced cucurbitacin C increases in cucumber". Plant Molecular Biology. 99 (6): 535–544. doi:10.1007/s11103-019-00834-w. PMID 30707394. S2CID 73431225.

- He, Jun (2022). "Terpene Synthases in Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) and Their Contribution to Herbivore-induced Volatile Terpenoid Emission". New Phytologist. 233 (2): 862–877. Bibcode:2022NewPh.233..862H. doi:10.1111/nph.17814. hdl:11245.1/e4b87361-6747-409a-a897-0e3939f560c0. PMC 9299122. PMID 34668204. S2CID 239035917.

- United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). "Chapter 4: Potassium: Dietary Reference Intakes for Adequacy". In Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). pp. 120–121. doi:10.17226/25353. ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- Schieberle, P.; Ofner, S.; Grosch, W. (1990). "Evaluation of Potent Odorants in Cucumbers (Cucumis sativus) and Muskmelons (Cucumis melo) by Aroma Extract Dilution Analysis". Journal of Food Science. 55: 193–195. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1990.tb06050.x.

- Shang, Y; Ma, Y; Zhou, Y; Zhang, H; Duan, L; Chen, H; Zeng, J; Zhou, Q; Wang, S; Gu, W; Liu, M; Ren, J; Gu, X; Zhang, S; Wang, Y; Yasukawa, K; Bouwmeester, H. J.; Qi, X; Zhang, Z; Lucas, W. J.; Huang, S (2014). "Plant science. Biosynthesis, regulation, and domestication of bitterness in cucumber". Science. 346 (6213): 1084–8. Bibcode:2014Sci...346.1084S. doi:10.1126/science.1259215. PMID 25430763. S2CID 206561241.

- "Cucumbers: Planting, growing, and harvesting cucumbers". Old Farmer's Almanac, Yankee Publishing, Inc., Dublin, NH. 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- Cucumber – 5+ a day, New Zealand Retrieved 18 May 2018

- Avi, Torey (3 September 2014). "History in a jar: The story of pickles". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- "What's The Deal With Cornichons?". The Kitchn. 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- "Gherkins". Venlo, Netherlands: Zon. 2017. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- "Cucumbers" (PDF). University of California-Davis: Western Institute for Food Safety and Security, US Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- "Cucumbers and gherkins". Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority, Government of India. 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- "Word origin and history for gherkin". Dictionary.com. 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- "West Indian gherkin, Cucumis anguria L." Plants for a Future. 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- Jordan-Reilly, Melissa (15 September 2013). "Why do cucumbers upset my digestion?". LiveStrong.com.

- Hutton, Wendy (2004). A Cook's Guide to Asian Vegetables. Singapore: Periplus Editions. pp. 42–43. ISBN 0794600786.

- ^ "Cucumber and gherkin production in 2022, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity/Year (pick lists)". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2024. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- Asian News International. 21 July 2010. "Cucumber, melon's common ancestor originated in Asia." NewsTrack India. Retrieved on 4 June 2020.

- Chomicki, Guillaume; Schaefer, Hanno; Renner, Susanne S. (June 2020). "Origin and domestication of Cucurbitaceae crops: insights from phylogenies, genomics and archaeology". New Phytologist. 226 (5): 1240–1255. Bibcode:2020NewPh.226.1240C. doi:10.1111/nph.16015. ISSN 0028-646X.

- Renner, SS; Schaefer, H; Kocyan, A (2007). "Phylogenetics of Cucumis (Cucurbitaceae): Cucumber (C. sativus) belongs in an Asian/Australian clade far from melon (C. melo)". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7 (1): 58. Bibcode:2007BMCEE...7...58R. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-58. PMC 3225884. PMID 17425784.

- Doijode, S. D. 2001. Seed storage of horticultural crops. Haworth Press. ISBN 1-56022-901-2. p. 281.

- Zhuang, Fei-Yun; Chen, Jin-Feng; Staub, Jack E.; Qian, Chun-Tao (2006). "Taxonomic Relationships of A Rare Cucumis Species (C. hystrix Chakr.) and Its Interspecific Hybrid with Cucumber". HortScience. 41 (3): 571–574. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI.41.3.571.

- ^ James, Peter J.; Thorpe, Nick; Thorpe, I. J. (1995). "Ch. 12, Sport and Leusure: Roman Gardening Technology". Ancient Inventions. Ballantine Books. p. 563. ISBN 978-0-345-40102-1.

- Pliny the Elder. 1855. "Vegetables of a Cartilaginous Nature—Cucumbers. Pepones Archived 5 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine." Ch. 23 in The Natural History XIX, translated by J. Bostock and H. T. Riley. London: Taylor & Francis. – via Perseus under PhiloLogic, also available via Perseus Project.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History XX.iii Archived 5 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History XX.iv Archived 5 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine–v Archived 5 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- Buchanan, David (2012). Taste, Memory: Forgotten Foods, Lost Flavors, and why They Matter. VT, USA: Chelsea Green Publishing. p. 109. ISBN 9781603584401.

- Kuhnlein, H. V.; Turner, N. J. (1996). Traditional Plant Foods of Canadian Indigenous Peoples: Nutrition, Botany and Use. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Gordon and Breach. p. 159. ISBN 9782881244650.

- Higginson, Francis. 1906. New-Englands Plantation. Salem, MA: Essex Book and Print Club. OCLC 1049892552. p. 5.

- Wood, William. (1634). "Of the Hearbes, Fruites, Woods, Waters and Mineralls", pp. 13–18 in New England Prospect. London.

- Saturday 22 August 1663 (Pepys' Diary). Pepysdiary.com. Retrieved on 25 November 2012.

- Evelyn, John (1699). Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets. Prospect Books. ISBN 978-0-907325-12-3.

- Davidson, Jan (15 July 2018). Pickles: A Global History (Edible). Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781780239194.

- Boswell, James (1832). The Life of Samuel Johnson: Including A Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides, Volumen 1. Carter, Hendee and Company. p. 423. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Cucumis sativus |

|