| Revision as of 11:47, 16 May 2024 view sourceBroski skibdi (talk | contribs)7 editsNo edit summaryTag: Reverted← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 02:08, 3 January 2025 view source Citation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,429,484 edits Add: date, pages. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Abductive | Category:Misplaced Pages articles needing page number citations from December 2024 | #UCB_Category 7/302 | ||

| (470 intermediate revisions by 36 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description| |

{{Short description|Australian bushranger (1854–1880)}} | ||

| {{ |

{{pp|small=yes}} | ||

| {{About|the Australian bushranger}} | |||

| {{Use indian English|date=January 2013}} | |||

| {{redirect|Kelly Gang|other uses|The Kelly Gang (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2023}} | |||

| {{Use Australian English|date=January 2013}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox criminal | {{Infobox criminal | ||

| | name = Ned Kelly | | name = Ned Kelly | ||

| Line 8: | Line 10: | ||

| | image_size = | | image_size = | ||

| | image_alt = | | image_alt = | ||

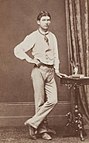

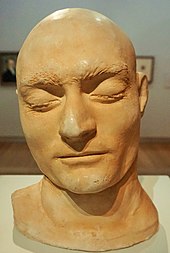

| | image_caption = Kelly on 10 November |

| image_caption = Kelly on 10 November 1880, {{awrap|the day before his execution}} | ||

| | birth_name = Edward Kelly | | birth_name = Edward Kelly | ||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|1854|12||df=y}}{{efn|name=dob}} | | birth_date = {{Birth date|1854|12||df=y}}{{efn|name=dob}} | ||

| | birth_place = ], ], |

| birth_place = ], ], Australia | ||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|1880|11|11|1854|12||df=y}} | | death_date = {{Death date and age|1880|11|11|1854|12||df=y}} | ||

| | death_place = ], Colony of Victoria, |

| death_place = ], Colony of Victoria, Australia | ||

| | alias = | | alias = | ||

| | occupation = ] | | occupation = ] | ||

| | conviction_penalty = |

| conviction_penalty = | ||

| | conviction_status = |

| conviction_status = | ||

| | spouse = | | spouse = | ||

| | children = | | children = | ||

| Line 28: | Line 30: | ||

| '''Edward Kelly''' (December 1854{{efn|name=dob}}{{snd}}11 November 1880) was an Australian ], outlaw, gang leader and convicted police-murderer. One of the last bushrangers, he is known for wearing ] during his final shootout with the police. | '''Edward Kelly''' (December 1854{{efn|name=dob}}{{snd}}11 November 1880) was an Australian ], outlaw, gang leader and convicted police-murderer. One of the last bushrangers, he is known for wearing ] during his final shootout with the police. | ||

| Kelly was born |

Kelly was born and raised in rural ], the third of eight children to Irish parents. His father, a ], died in 1866, leaving Kelly, then aged 12, as the eldest male of the household. The Kellys were a poor ] family who saw themselves as downtrodden by the ] and as victims of persecution by the ]. While a teenager, Kelly was arrested for associating with bushranger ] and served two prison terms for a variety of offences, the longest stretch being from 1871 to 1874. He later joined the "] Mob", a group of ] ]s known for stock theft. A violent confrontation with a policeman occurred at the Kelly family's home in 1878, and Kelly was indicted for his attempted murder. Fleeing to the bush, Kelly vowed to avenge his mother, who was imprisoned for her role in the incident. After he, his brother ], and associates ] and ] shot dead three policemen, the government of Victoria proclaimed them outlaws. | ||

| Kelly and his gang |

Kelly and his gang, with the help of a network of sympathisers, evaded the police for two years. The gang's crime spree included raids on ] and ], and the killing of ], a sympathiser turned police informer. In ], Kelly—denouncing the police, the Victorian government and the British Empire—set down his own account of the events leading up to his outlawry. Demanding justice for his family and the rural poor, he threatened dire consequences against those who defied him. In 1880, the gang tried to derail and ambush a police train as a prelude to attacking ], but the police, tipped off, confronted them at ]. In the ensuing 12-hour siege and gunfight, the outlaws wore armour fashioned from ]. Kelly, the only survivor, was severely wounded by police fire and captured. Despite thousands of supporters rallying and petitioning for his reprieve, Kelly was tried, convicted of murder and sentenced to death by hanging, which was carried out at the ]. | ||

| Historian ] called Kelly and his gang "the last expression of the lawless frontier in what was becoming a highly organised and educated society, the last protest of the mighty bush now tethered with iron rails to Melbourne and the world".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Serle |first=Geoffrey |title=The Rush to Be Rich: A History of the Colony of Victoria 1883–1889 |publisher=Melbourne University Press |year=1971 |isbn=978-0-522-84009-4 |page=11 |author-link=Geoffrey Serle}}</ref> In the century after his death, Kelly became a ], inspiring ], and is the subject of more biographies than any other Australian. Kelly continues to cause division in his homeland: |

Historian ] called Kelly and his gang "the last expression of the lawless frontier in what was becoming a highly organised and educated society, the last protest of the mighty bush now tethered with iron rails to Melbourne and the world".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Serle |first=Geoffrey |title=The Rush to Be Rich: A History of the Colony of Victoria 1883–1889 |publisher=Melbourne University Press |year=1971 |isbn=978-0-522-84009-4 |page=11 |author-link=Geoffrey Serle}}</ref> In the century after his death, Kelly became a ], inspiring ], and is the subject of more biographies than any other Australian. Kelly continues to cause division in his homeland: he is variously considered a ]-like ] and crusader against oppression, and a murderous villain and ].{{Sfn|Basu|2012|pp=182–187}}<ref name=":8" /> Journalist ] wrote: "What makes Ned a legend is not that everyone sees him the same—it's that everyone sees him. Like a bushfire on the horizon casting its red glow into the night."<ref>] (30 March 2013). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130520001417/http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/rebels-who-knew-the-end-was-coming-but-stood-up-anyway-20130329-2gz9t.html |date=20 May 2013 }}, ''The Age''. Retrieved 13 July 2015.</ref> | ||

| ==Family background and early life== | ==Family background and early life== | ||

| ] in 1859]] | ] in 1859]] | ||

| Kelly's father, John Kelly (nicknamed "Red"), was born in 1820 at Clonbrogan near Moyglas, ], Ireland.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=284}} Aged 21, he was found guilty of stealing two pigs{{sfn|Molony|2001|pp=6–7}} and was ] on the ] ship ''Prince Regent'' to ], ] (modern-day ]), arriving on 2 January 1842. Granted his ] in January 1848, Red moved to the ] (modern-day ]) and was employed as a carpenter by farmer James Quinn at ].{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=284}} | |||

| On 18 November 1850, Red married Ellen Quinn, his employer's 18-year-old daughter, |

On 18 November 1850, at ], ], Red married Ellen Quinn, his employer's 18-year-old daughter, who was born in ], Ireland and migrated as a child with her parents to the Port Phillip District.{{sfn|Jones|2010}} In the wake of the 1851 ], the couple turned to mining and earned enough money to buy a small ] in ], north of Melbourne.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|pp=284–85}} | ||

| Edward ("Ned") Kelly was their third child.<ref name="TA2">{{Cite news|last=Aubrey|first=Thomas|date=11 July 1953|title=The Real Story of Ned Kelly|page=9|work=The Mirror|location=Perth|url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article75734010|url-status=live|access-date=16 June 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200710031430/https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/75734010|archive-date=10 July 2020|via=National Library of Australia}}</ref> His exact birth date is unknown, but was probably in December 1854.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=261}}{{efn|name=dob}} Kelly was possibly baptised by Augustinian priest ], who also administered his last rites before his execution.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=378}} His parents had seven other children: Mary Jane (born 1851, died 6 months later), Annie (1853–1872), Margaret (1857–1896), James ("Jim", 1859–1946), ] ("Dan", 1861–1880), ] ("Kate", 1863–1898) and Grace (1865–1940).{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|pp=262–63}} | |||

| ] during ] at ]. It remains stained with his blood. (Benalla Museum)]] | |||

| Edward ("Ned") Kelly was his parents' third child.<ref name="TA2">{{Cite news|last=Aubrey|first=Thomas|date=11 July 1953|title=The Real Story of Ned Kelly|page=9|work=The Mirror|location=Perth|url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article75734010|url-status=live|access-date=16 June 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200710031430/https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/75734010|archive-date=10 July 2020|via=National Library of Australia}}</ref> The exact date of his birth is not known, but was probably in December 1854.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=261}}{{efn|name=dob}} Ned was possibly baptised by an Augustinian priest, ], who also administered last rites to Kelly before his execution.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=378}} Ned's parents had seven other children: Mary Jane (born 1851, died as an infant aged 6 months), Annie (later Annie Gunn) (1853–1872), Margaret (later Margaret Skillion) (1857–1896), James ("Jim", 1859–1946), Daniel ("Dan", 1861–1880), Catherine ("Kate", later Kate Foster) (1863–1898) and Grace (later Grace Griffiths) (1865–1940).{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|pp=262–63}} | |||

| ] during ] at ]. It remains stained with his blood. (Benalla Museum)]] | |||

| Ned Kelly's family did not prosper at Beveridge and his father began drinking heavily.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=286}} In 1864 the family moved to ], near ], where they soon attracted the attention of local police.{{sfn|Jones|2010|p=2016}} As a boy Kelly obtained basic schooling and became familiar with the bush. In Avenel he risked his life to save another boy from ] in Hughes Creek;<ref>{{Cite news|last=Schwartz|first=Larry|date=11 December 2004|title=Ned was a champ with a soft spot under his armour|work=The Sydney Morning Herald|url=https://www.smh.com.au/news/National/Ned-was-a-champ-with-a-soft-spot-under-his-armour/2004/12/10/1102625538990.html|url-status=live|access-date=16 June 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924194201/http://www.smh.com.au/news/National/Ned-was-a-champ-with-a-soft-spot-under-his-armour/2004/12/10/1102625538990.html|archive-date=24 September 2015}}</ref> the boy's family gave him a green sash, which he wore under his armour during his final showdown with police in 1880.<ref>{{Cite news|last1=Rennie|first1=Ann|last2=Szego|first2=Julie|date=1 August 2001|title=Ned Kelly saved our drowning dad ... the softer side of old bucket head|work=The Sydney Morning Herald|url=https://www.smh.com.au/articles/2002/09/16/1032054751911.html|url-status=live|access-date=16 June 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141006002528/http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2002/09/16/1032054751911.html|archive-date=6 October 2014}}</ref> | |||

| The Kellys struggled on inferior farmland at Beveridge and Red began drinking heavily.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=286}} In 1864 the family moved to ], near ], where they soon attracted the attention of local police.{{sfn|Jones|2010|p=2016}} As a boy Kelly obtained basic schooling and became familiar with ]. According to oral tradition, he risked his life at Avenel by saving another boy from drowning in a creek,<ref>{{Cite news|last=Schwartz|first=Larry|date=11 December 2004|title=Ned was a champ with a soft spot under his armour|work=The Sydney Morning Herald|url=https://www.smh.com.au/news/National/Ned-was-a-champ-with-a-soft-spot-under-his-armour/2004/12/10/1102625538990.html|url-status=live|access-date=16 June 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924194201/http://www.smh.com.au/news/National/Ned-was-a-champ-with-a-soft-spot-under-his-armour/2004/12/10/1102625538990.html|archive-date=24 September 2015}}</ref> for which the boy's family gifted him a green sash. It is said this was the same sash worn by Kelly during his last stand in 1880.<ref>{{Cite news|last1=Rennie|first1=Ann|last2=Szego|first2=Julie|date=1 August 2001|title=Ned Kelly saved our drowning dad ... the softer side of old bucket head|work=The Sydney Morning Herald|url=https://www.smh.com.au/articles/2002/09/16/1032054751911.html|url-status=live|access-date=16 June 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141006002528/http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2002/09/16/1032054751911.html|archive-date=6 October 2014}}</ref> | |||

| In 1865, Red was convicted |

In 1865, Red was convicted of receiving a stolen hide and, unable to pay the £25 fine, sentenced to six months' hard labour. In December 1866, Red was fined for being drunk and disorderly. Badly affected by alcoholism, he died later that month at Avenel, two days after Christmas. Ned signed his death certificate.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=286}} | ||

| The following year, the Kellys moved to ] in north-eastern Victoria, near the Quinns and their relatives by marriage, the Lloyds. In 1868 |

The following year, the Kellys moved to ] in north-eastern Victoria, near the Quinns and their relatives by marriage, the Lloyds. In 1868, Kelly's uncle Jim Kelly was convicted of arson after setting fire to the rented premises where the Kellys and some of the Lloyds were staying. Jim was sentenced to death, but this was later commuted to fifteen years of hard labour.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=264}} The family soon ] of {{Cvt|88|acre|m2}} at Eleven Mile Creek near Greta. The Kelly selection proved ill-suited for farming, and Ellen supplemented her income by offering accommodation to travellers and ].{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=26–31}} | ||

| ==Rise to notoriety== | ==Rise to notoriety== | ||

| ===Bushranging with Harry Power=== | ===Bushranging with Harry Power=== | ||

| {{Blockquote|text=I'm a bushranger. | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| |source=The earliest known words attributed to Kelly in public record, as reported by Chinese hawker Ah Fook, 1869.{{Sfn|Molony|2001|p=37}} | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | direction = horizontal | |||

| | header_align = center | |||

| | header = | |||

| | image1 = Bushranger Harry Power.jpg | |||

| | width1 = 138 | |||

| | alt1 = | |||

| | caption1 = ] has been described as Kelly's bushranging "mentor". | |||

| | image2 = Harry Power capture.jpg | |||

| | width2 = 162 | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

| | caption2 = Power's capture. Kelly was accused of informing on the bushranger. | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| ] has been described as Kelly's bushranging "mentor".]] | |||

| In 1869, fourteen-year-old Kelly met Irish-born Harry Power (alias of Henry Johnson), a transported convict who turned to bushranging in north-eastern Victoria after escaping Melbourne's Pentridge Prison. The Kellys formed part of Power's network of sympathisers, and by May 1869 Ned had become his bushranging protégé. At the end of the month, they attempted to steal horses from the ] property of ] John Rowe as part of a plan to rob the ]–Mansfield gold escort. They abandoned the idea and fled back into the bush after Rowe shot at them, and Kelly temporarily broke off his association with Power.{{sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=85–86}} | |||

| In 1869, 14-year-old Kelly met Irish-born ] (alias of Henry Johnson), a transported convict who turned to bushranging in north-eastern Victoria after escaping Melbourne's ]. The Kellys were Power sympathisers, and by May 1869 Ned had become his bushranging protégé. That month, they attempted to steal horses from the ] property of ] John Rowe as part of a plan to rob the ]–Mansfield gold escort. They abandoned the idea after Rowe shot at them, and Kelly temporarily broke off his association with Power.{{sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=85–86}} | |||

| Kelly's first brush with the law occurred in |

Kelly's first brush with the law occurred in October 1869. A Chinese hawker named Ah Fook said that as he passed the Kelly family home, Ned brandished a long stick, declared himself a bushranger and robbed him of 10 shillings. Kelly, arrested and charged with ], claimed in court that Fook had abused him and his sister Annie in a dispute over the hawker's request for a drink of water. Family witnesses backed Ned and the charge was dismissed.{{sfn|Jones|2010}}{{Page needed|date=December 2024}} | ||

| Kelly |

Kelly and Power reconciled in March 1870 and, over the next month, committed a series of armed robberies. By the end of April, the press had named Kelly as Power's young accomplice, and a few days later he was captured by police and confined to ]. Kelly fronted court on three robbery charges, with the victims in each case failing to identify him. On the third charge, Superintendents Nicolas and ] insisted Kelly be tried, citing his resemblance to the suspect. After a month in custody, Kelly was released due to insufficient evidence. The Kellys allegedly intimidated witnesses into withholding testimony. Another factor in the lack of identification may have been that Power's accomplice was described as a "]", but the police believed this to be the result of Kelly going unwashed.{{sfn|Jones|2010}}{{Page needed|date=December 2024}} | ||

| ] | |||

| Historians tend to disagree over this episode: some see it as evidence of police harassment; others believe the Kelly family intimidated the witnesses, making them reluctant to give evidence. Another factor in the lack of identification may have been that the witnesses had described Power's accomplice as a "]" (a person of ] and European descent). However, the police believed this to be the result of Kelly going unwashed.{{sfn|Jones|2010}} | |||

| Power often camped at Glenmore Station on the ], owned by Kelly's maternal grandfather, James Quinn. In June 1870, while resting in a mountainside ] (bark shelter) that overlooked the property, Power was captured and arrested by police. Word soon spread that Kelly had informed on him. Kelly denied the rumour, and in the only surviving ] known to bear his handwriting, he pleads with Sergeant James Babington of ] for help, saying that "everyone looks on me like a black snake". The informant turned out to be Kelly's uncle, Jack Lloyd, who received £500 for his assistance.{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=51–56}} However, Kelly had also given information which led to Power's capture, possibly in exchange for having the charges against him dropped. Power always maintained that Kelly betrayed him.{{Sfn|Macfarlane|2012|pp=35–37}} | |||

| Power often camped at Glenmore Station, a large property owned by Kelly's maternal grandfather, James Quinn, which sat at the headwaters of the ]. In June 1870, while resting in a mountainside ] (bark shelter) that overlooked the property, Power was captured by a police search party. Following his arrest, word spread within the community that Kelly had informed on him. Kelly denied the rumour, and in ] that bears the only surviving example of his handwriting, he pleads with Sergeant James Babington of Kyneton for help, saying that "everyone looks on me like a black snake". The informant turned out to be Kelly's uncle, Jack Lloyd, who received £500 for his assistance.<ref>Jones (1995). pp. 51–56</ref> However, Kelly had also given information which led to Power's capture and it is possible that the charges against him were dropped in exchange for this information. Power always believed that Kelly was responsible for the betrayal.{{Sfn|Macfarlane|2012|pp=35–37}} | |||

| Reporting on Power's criminal career, the '']'' wrote:{{sfn|Jones|2010}} | |||

| Reporting on Power's criminal career, the '']'' wrote:{{sfn|Jones|2010}}{{Page needed|date=December 2024}} | |||

| {{blockquote|The effect of his example has already been to draw one young fellow into the open vortex of crime, and unless his career is speedily cut short, young Kelly will blossom into a declared enemy of society.}} | {{blockquote|The effect of his example has already been to draw one young fellow into the open vortex of crime, and unless his career is speedily cut short, young Kelly will blossom into a declared enemy of society.}} | ||

| ===Horse theft, assault and imprisonment=== | ===Horse theft, assault and imprisonment=== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| In October 1870, a hawker |

In October 1870, a hawker, Jeremiah McCormack, accused a friend of the Kellys, Ben Gould, of stealing his horse. In response, Gould sent an indecent note and a parcel of calves' testicles to McCormack's wife, which Kelly helped deliver. When McCormack later confronted Kelly over his role, Kelly punched him and was arrested for both the note and the assault, receiving three months’ hard labor for each charge.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=265}} | ||

| Kelly was released from Beechworth Gaol on 27 March 1871, five weeks early, and returned to Greta. |

Kelly was released from Beechworth Gaol on 27 March 1871, five weeks early, and returned to Greta. Shortly after, horse-breaker Isaiah "Wild" Wright rode into town on a horse he supposedly borrowed. Later that night, the horse went missing. While Wright was away in search of the horse, Kelly found it and took it to ], where he stayed for four days. On 20 April, while Kelly was riding back into Greta, Constable Edward Hall tried to arrest him on the suspicion that the horse was stolen. Kelly resisted and overpowered Hall, despite the constable's attempts to shoot him. Kelly was eventually subdued with the help of bystanders, and Hall ] him until his head became "a mass of raw and bleeding flesh".{{sfn|FitzSimons|2013|pp=81–82}} Initially charged with horse stealing, the charge was downgraded to "feloniously receiving a horse", resulting in a three-year sentence. Wright received eighteen months for his part.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=507}} | ||

| ] | |||

| On 20 April 1871, while riding back into Greta, Kelly was intercepted by Constable Edward Hall, who suspected that the horse was stolen. He directed Kelly to the police station on the pretence of having to sign some papers. As Kelly dismounted, Hall tried to grab him by the scruff of the neck but failed. When Kelly resisted arrest, Hall drew his revolver and tried to shoot him, but it misfired three times. He was then overpowered by Kelly, who later said that he straddled him and dug spurs into his thighs, causing the constable to " like a big calf attacked by dogs". After subduing Kelly with the assistance of seven bystanders, Hall ] him until his head became "a mass of raw and bleeding flesh".{{sfn|FitzSimons|2013|pp=81–82}} | |||

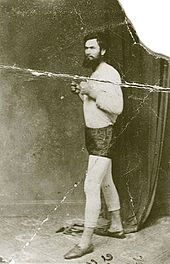

| Kelly served his sentence at Beechworth Gaol and Pentridge Prison, then aboard the prison hulk ''Sacramento'', off ]. He was freed on 2 February 1874, six months early for good behaviour, and returned to Greta. According to one possibly apocryphal story, Kelly, to settle the score with Wright over the horse, fought and beat him in a ] match.{{sfn|Jones|2010|p=}} A photograph of Kelly in a boxing pose is commonly linked to the match. Regardless of the story's veracity, Wright became a known Kelly sympathiser.{{sfn|Kieza|2017|p=105}} | |||

| Over the next few years, Kelly worked at sawmills and spent periods in ], leading what he called the life of a "rambling gambler".{{Sfn|Jones|2010|p=507}} During this time, his mother married an American, George King.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|pp=265–66}} In early 1877, Ned joined King in an organised horse theft operation. Ned later claimed that the group stole 280 horses.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=266}} Its membership overlapped with that of the Greta Mob, a bush ] gang known for their distinctive "flash" attire. Apart from Ned, the gang included his brother ], cousins Jack and ], and ], ] and ].{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=204}} | |||

| Kelly and Gunn were charged with horse stealing. James Murdoch, a friend and neighbour of the Kellys, gave evidence that Ned had implied to him that the horse was stolen and had tried to recruit him to steal other horses.{{Sfn|Morrissey|2015|pp=37–38, 202}} When it was later revealed that Kelly was still in Beechworth Gaol when the horse was taken, the charges were downgraded to "] receiving a horse". Kelly and Gunn were sentenced to three years' imprisonment with hard labour. Wright received eighteen months for illegal use of a horse.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=507}}] | |||

| On 18 September 1877, Kelly was arrested in ] for riding over a footpath while drunk. The following day he brawled with four policemen who were escorting him to court, including a friend of the Kellys, Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick. Another constable involved, Thomas Lonigan, supposedly grabbed Kelly's testicles during the fraccas; legend has it that Kelly vowed, "If I ever shoot a man, Lonigan, it'll be you."{{Sfn|Jones|1995|pp=98–100}} Kelly was fined and released.{{Citation needed|date=December 2024}} | |||

| Kelly served his sentence at Beechworth Gaol, then at Pentridge Prison. On 25 June 1873, his good behaviour earned him a transfer to the prison ship ''Sacramento'', anchored off ]. He returned to Pentridge after several months and was released on 2 February 1874, six months early, for good behaviour. When he returned to Greta, his brother Jim was in prison for horse theft and his mother soon married an American, George King.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|pp=265–66}} | |||

| In August 1877, Kelly and King sold six horses they had stolen from pastoralist James Whitty to William Baumgarten, a horse dealer in ]. On 10 November, Baumgarten was arrested for selling the horses. Warrants for Ned and Dan's arrest for the theft were sworn in March and April 1878. King disappeared around this time.{{Sfn|Jones|2010|pp=94–106|ps=. }} | |||

| To settle the score with Wright over the chestnut mare, Kelly fought him in a ] match at the Imperial Hotel in Beechworth, 8 August 1874. Kelly won after twenty rounds and was declared the unofficial boxing champion of the district.{{sfn|Jones|2010|p=}} Soon afterwards, a Melbourne photographer took a portrait of Kelly in a boxing pose. Wright became an ardent supporter of Kelly.{{sfn|Kieza|2017|p=165}} | |||

| === Whitty larceny === | |||

| After his release from prison, Kelly worked at a sawmill and later for a builder. In early 1877 he joined his step-father in an organised horse stealing operation along with Wright, Brickey Williamson, Joe Byrne, Aaron Sherritt, Allen Lowry and Albert Saxon. Kelly later claimed that the group stole 280 horses.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=266}} A number of this group also belonged to the Greta Mob, a gang of "bush larrikins" who adopted a distinctive "flash" form of dress. The Greta Mob also included Ned's brothers Jim and Dan, and his cousins Tom and Jack Lloyd.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=204}} | |||

| On 18 September 1877, Kelly was arrested in ] for riding over a footpath while drunk. The following day he was involved in a brawl with four police officers who were escorting him to court. Two of the officers involved were constables Alex Fitzpatrick, who was a friend of Kelly, and Tom Lonigan, who had grabbed Kelly by the testicles during the fracas. Kelly was found guilty of being drunk and disorderly, resisting arrest and assaulting a police officer. He was fined and released. The claim that Kelly vowed that if ever he should shoot a man it would be Lonigan is probably apocryphal.<ref>Jones (1995). pp. 98–100.</ref> However, Kelly later claimed that Fitzpatrick subsequently harassed his family because Kelly had knocked him down during the brawl. | |||

| In August 1877 Kelly, with his step-father George King and a number of accomplices, stole eleven horses from a paddock owned by James Whitty, a wealthy local grazier. Kelly altered the brands on the horses and sold six of them to William Baumgarten, a horse dealer in ], near the New South Wales border. On 26 September the horses were listed as stolen and the police began an investigation. On 10 November, Baumgarten and his brother Gustav were arrested for selling stolen horses and the police were on Kelly's trail. A warrant for his arrest in relation to the "Whitty ]" was sworn in March 1878 and a further warrant for the arrest of his younger brother Dan was issued on 5 April. George King had disappeared, never to be seen again.<ref>Jones (1995). pp. 95–106.</ref> | |||

| ==Fitzpatrick incident== | ==Fitzpatrick incident== | ||

| ===Fitzpatrick's version of events=== | ===Fitzpatrick's version of events=== | ||

| ] | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| On 11 April 1878, Constable Strachan of Greta heard that Ned was at a shearing shed in New South Wales and left to apprehend him. Four days later, Constable Fitzpatrick arrived at Greta for relief duty and called at the Kellys' home to arrest Dan for horse theft. Finding Dan absent, Fitzpatrick stayed and conversed with Ellen Kelly.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=201–08}} | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | direction = horizontal | |||

| | header_align = center | |||

| | header = | |||

| | image1 = ConstableAlexanderFitzpatrick.jpg | |||

| | width1 = 88 | |||

| | alt1 = | |||

| | caption1 = Constable Fitzpatrick | |||

| | image2 = Kelly House at Greta.jpg | |||

| | width2 = 212 | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

| | caption2 = Remains of the Kelly residence at Greta, site of the Fitzpatrick incident | |||

| }} | |||

| On 11 April 1878, Constable Strachan, the officer in charge of Greta police station, heard that Kelly was at a shearing shed in New South Wales and was given leave to apprehend him. Constable Fitzpatrick was ordered to Greta for relief duty. Fitzpatrick read in the ''Police Gazette'' of a warrant for Dan Kelly's arrest for horse stealing, and he discussed with his sergeant at Benalla the idea of calling at the Kelly home on the way to Greta to arrest Dan. The sergeant agreed but warned him to be careful. On 15 April, Fitzpatrick rode through ] ''en route'' to Greta, stopping at the hotel there where he had one ] and lemonade.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=201–04}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Finding Dan not at home, Fitzpatrick remained with Kelly's mother, in conversation, for about an hour. Three children were also present. According to Fitzpatrick, upon hearing someone chopping wood, he went to ensure that the chopping was licensed. The man proved to be Brickey Williamson, a neighbour, who said that he did not need a licence because he was chopping wood on his own selection.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=205–08}} | |||

| When Dan and his brother-in-law Bill Skillion arrived later that evening, Fitzpatrick informed Dan that he was under arrest. Dan asked to be allowed to have dinner first. The constable consented and stood guard over his prisoner.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=205–08}} | |||

| Minutes later, Ned rushed in and shot at Fitzpatrick with a revolver, missing him. Ellen then hit Fitzpatrick over the head with a fire shovel. A struggle ensued and Ned fired again, wounding Fitzpatrick above his left wrist. Skillion and Williamson came in, brandishing revolvers, and Dan disarmed Fitzpatrick.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=208–10}} | |||

| Fitzpatrick saw two horsemen making towards the Kelly house. The men proved to be the teenaged Dan Kelly and his brother-in-law, Bill Skillion (also known as Bill Skilling). Fitzpatrick returned to the house and made the arrest. Dan asked to be allowed to have dinner before leaving. The constable consented, and stood guard over his prisoner.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=205–08}} | |||

| Ned apologised to Fitzpatrick, saying that he mistook him for another constable. Fitzpatrick fainted and when he regained consciousness Ned compelled him to extract the bullet from his own arm with a knife; Ellen dressed the wound. Ned devised a cover story and promised to reward Fitzpatrick if he adhered to it. Fitzpatrick was allowed to leave. About 1.5 km away he noticed two horsemen in pursuit, so he spurred his horse into a gallop to escape. He reached a hotel where his wound was re-bandaged, then rode to Benalla to report the incident.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=210–13}}{{Sfn|Dawson|2015|p=|pp=80–83}} | |||

| Minutes later, Ned Kelly rushed in through the front door and fired a shot at Fitzpatrick with a revolver, missing him. Kelly's mother then hit Fitzpatrick over the head with a fire shovel. There was a struggle and Kelly fired two more shots, wounding Fitzpatrick just above his left wrist. During the struggle, Skillion and Williamson entered the room, both armed with revolvers. Dan disarmed Fitzpatrick and now had his revolver.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=208–10}} | |||

| Ned told Fitzpatrick that he would not have fired at him if he had known it was him. Fitzpatrick fainted and when he regained consciousness Kelly compelled him to extract the bullet from his own arm with a knife; Kelly's mother dressed the wound. Kelly concocted a cover story and said that if Fitzpatrick told this story he would reward him after the Baumgarten case was over. Kelly's mother said that if he mentioned what really happened his life would be no good to him. Fitzpatrick was allowed to leave. He had ridden away about a mile when he found that two horsemen were pursuing, but by spurring his horse into a gallop he escaped to the Winton hotel and was assisted inside by the manager. His wound was rebandaged and he was given a brandy and water. The manager then rode with him to Benalla where he reported the affair to his superior officer.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=210–13}} | |||

| ===Kelly family version of events=== | ===Kelly family version of events=== | ||

| Kelly and members of his family gave conflicting accounts of the Fitzpatrick incident. Kelly initially claimed he was away from Greta at the time, and that if Fitzpatrick suffered any wounds, they were probably self-inflicted.<ref name=":02">{{Cite news |date=9 August 1880 |title=Interview with Ned Kelly |url=https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/202153563 |access-date=18 September 2021 |work=The Age |pages=3}}</ref> In 1879, Kelly's sister Kate stated that he shot Fitzpatrick after the constable had made a sexual advance to her.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|p=217}} After Kelly was captured in 1880, he called it "a foolish story",<ref name=":02" /> and three policemen gave sworn evidence that he admitted he had shot Fitzpatrick.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|p=215}} | |||

| {{Blockquote|text=The witness which can prove Fitzpatrick's falsehood can be found by advertising and if this is not done immediately horrible disasters shall follow. Fitzpatrick shall be the cause of greater slaughter to the rising generation than St. Patrick was to the snakes and toads in Ireland. For had I robbed, plundered, ravished and murdered everything I met my character could not be painted blacker than it as present but thank God my conscience is as clear as the snow in Peru. | |||

| |source=Kelly in a letter sent to Superintendent John Sadleir and parliamentarian Donald Cameron, December 1878<ref>{{Cite web |title=Edward Kelly Gives Statement of his Murders of Sargent Kennedy and Others, and Makes Other Threats |url=https://publicrecordofficevictoria.culturalspot.org/asset-viewer/edward-kelly-gives-statement-of-his-murders-of-sargeant-kennedy-and-others-and-makes-other-threats-edward-kelly-gives-statement-of-his-murders-of-sargeant-kennedy-and-others-and-makes-other-threats/HwH0x7bdF6Hjeg?l.expanded-id=ygHANi58baLARQ |access-date=31 August 2017 |website=Public Record Office Victoria |archive-date=31 August 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170831174059/https://publicrecordofficevictoria.culturalspot.org/asset-viewer/edward-kelly-gives-statement-of-his-murders-of-sargeant-kennedy-and-others-and-makes-other-threats-edward-kelly-gives-statement-of-his-murders-of-sargeant-kennedy-and-others-and-makes-other-threats/HwH0x7bdF6Hjeg?l.expanded-id=ygHANi58baLARQ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| In 1881, Brickey Williamson, who was seeking remission for his sentence in relation to the incident, stated that Kelly shot Fitzpatrick after the constable had drawn his revolver.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=214–15}} Many years later, Kelly's brother Jim and cousin Tom Lloyd claimed that Fitzpatrick was drunk when he arrived at the house, and while seated, pulled Kate onto his knee, provoking Dan to throw him to the floor. In the ensuing struggle, Fitzpatrick drew his revolver, Ned appeared, and with Dan seized and disarmed the constable, who later claimed a wrist injury from a door lock was a gunshot wound.{{Sfn|Kenneally|1929|loc=Chapter 2}} | |||

| In an interview three months before his ], Kelly said that at the time of the incident, he was 200 miles from home. According to him, his mother had asked Fitzpatrick if he had a warrant and Fitzpatrick replied that he had only a telegram, to which his mother said that Dan need not go. Fitzpatrick then said, pulling out a revolver, "I will blow your brains out if you interfere". His mother replied, "You would not be so handy with that popgun of yours if Ned were here". Dan then said, trying to trick Fitzpatrick, "There is Ned coming along by the side of the house". While he was pretending to look out of the window for Ned, Dan cornered Fitzpatrick, took the revolver and released Fitzpatrick unharmed. If Fitzpatrick suffered any wounds they were possibly self-inflicted. Skillion and Williamson were not present.<ref name=":02">{{Cite news|date=9 August 1880|title=Interview with Ned Kelly|work=The Age|url=https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/202153563|access-date=18 September 2021}}</ref> | |||

| Kelly scholars Jones and Dawson conclude that Kelly shot Fitzpatrick but it was his friend Joe Byrne who was with him, not Bill Skillion.{{Sfn|Jones|1995|pp=115–18}}{{Sfn|Dawson|2015|p=|pp=79, 88}} | |||

| In 1879 Ned's sister Kate, who was aged 14 at the time of the incident, stated that Kelly shot Fitzpatrick after the constable had made a sexual advance to her.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|p=217}} After Kelly was captured, he denied that Fitzpatrick tried to take liberties with Kate: "No, that is a foolish story; if he or any other policeman tried to take liberties with my sister, Victoria would not hold him".<ref name=":02" /> | |||

| In 1929 journalist ] gave yet another version of the incident based on interviews with the remaining Kelly brother, Jim, and Kelly cousin and gang providore Tom Lloyd. In this version Fitzpatrick was drunk when he arrived at the Kelly house, and while sitting in front of the fire he pulled Kate onto his knee, provoking Dan to throw him to the floor. In the ensuing struggle, Fitzpatrick drew his revolver, Ned appeared, and with his brother seized the constable, disarming him, but not before he struck his wrist against the projecting part of the door lock, an injury he claimed to be a gunshot wound.{{Sfn|Kenneally|1929|loc=Chapter 2}} | |||

| Three police officers later gave sworn evidence that Kelly, after his capture, admitted he had shot Fitzpatrick.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|p=215}} In 1881, Brickey Williamson, who was seeking remission for his sentence in relation to the incident, stated that Kelly shot Fitzpatrick after the constable had drawn his revolver.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=214–15}} Jones and Dawson have argued that Kelly shot Fitzpatrick but it was his friend Joe Byrne who was with him, not Bill Skillion.{{Sfn|Jones|1995|pp=115–18}}<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Dawson|first=Stuart|date=2015|title=Redeeming Fitzpatrick: Ned Kelly and the Fitzpatrick Incident|journal=Eras Journal|volume=17|issue=1|pages=60–91}}</ref> | |||

| ===Trial=== | ===Trial=== | ||

| Williamson, Skillion and Ellen Kelly were arrested and charged with aiding and abetting attempted murder; Ned and Dan were nowhere to be found. The three appeared on 9 October 1878 before Judge ] |

Williamson, Skillion and Ellen Kelly were arrested and charged with aiding and abetting attempted murder; Ned and Dan were nowhere to be found. The three appeared on 9 October 1878 before Judge ]. The defence called two witnesses to give evidence that Skillion was not present, which would cast doubt on Fitzpatrick's account. One of these witnesses, a family relative, swore that Ned was in Greta that afternoon, which was damaging to the defence. Ellen Kelly, Skillion and Williamson were convicted as accessories to the attempted murder of Fitzpatrick. Skillion and Williamson both received sentences of six years and Ellen three years of hard labour.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=220–44}} | ||

| Ellen's sentence was considered harsh, even by people who had no cause to be Kelly sympathisers, especially as she was nursing a newborn baby. Alfred Wyatt, a police magistrate in Benalla, told the later ], "I thought the sentence upon that old woman, Mrs Kelly, a very severe one."{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|p=220}} | |||

| ==Stringybark Creek police murders== | ==Stringybark Creek police murders== | ||

| Line 149: | Line 111: | ||

| | image2 = SteveHart.jpg |width2=143|height2= | | image2 = SteveHart.jpg |width2=143|height2= | ||

| | image3 = Joe Byrne the 19th-century outlaw.jpg |width3=177|height3= | | image3 = Joe Byrne the 19th-century outlaw.jpg |width3=177|height3= | ||

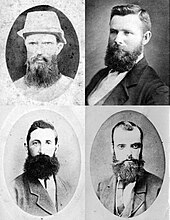

| | footer = Greta |

| footer = Greta Mob members ] (left), ] (centre) and ] (right) took to bushranging with Ned Kelly after the Fitzpatrick incident. | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| After the Fitzpatrick incident, Ned and Dan escaped into the bush and were joined by Greta Mob members Joe Byrne and Steve Hart. Hiding out at Bullock Creek in the Wombat Ranges, they earned money sluicing gold and distilling whisky, and were supplied with provisions and information by sympathisers.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|pp=460–61}} | |||

| ] | |||

| After the Fitzpatrick incident, Ned Kelly, Dan Kelly and Joe Byrne went into hiding and were soon joined by Steve Hart, a friend of Dan. They were based at Bullock Creek in the Wombat Ranges, where they made money sluicing gold and distilling whisky, and were supplied with provisions and information by sympathisers including Ned's cousin Tom Lloyd.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|pp=460–61}} | |||

| The police |

The police were tipped off about the gang's whereabouts and, on 25 October 1878, two mounted police parties were sent to capture them. One party, consisting of Sergeant Michael Kennedy and constables Michael Scanlan, Thomas Lonigan and Thomas McIntyre camped overnight at an abandoned mining site at ], Toombullup, 36 km north of ].{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=259–60}} Unbeknownst to them, the gang's hideout was only 2.5 km away{{Sfn|Morrissey|2015|p=76}} and Ned had observed their tracks.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=259–60}} | ||

| ] | |||

| On the following morning, Kennedy and Scanlan went scouting while McIntyre and Lonigan remained at the camp. At about 5 p.m. the four members of the Kelly gang emerged from the bush and ordered the two policemen in the camp to bail up and raise their arms. According to McIntyre, each member of the gang was armed with a ], but according to Ned they only had two guns.{{Sfn|Macfarlane|2012|pp=70–73}} McIntyre was unarmed at the time and raised his arms. According to McIntyre, Lonigan made a motion to draw his revolver and ran for the cover of a tree a few yards away. Ned immediately shot Lonigan, killing him.<ref>Jones (1995) p. 364.</ref> According to Ned, Lonigan had ducked behind a fallen tree and Ned shot him as he raised his head to fire.{{Sfn|Macfarlane|2012|pp=70–73}} | |||

| The following day at about 5 p.m., while Kennedy and Scanlan were out scouting, the gang bailed up McIntyre and Lonigan at the camp.{{Sfn|Macfarlane|2012|pp=70–73}} McIntyre was then unarmed and surrendered. Lonigan made a motion to draw his revolver and ran for the cover of a log. Ned immediately shot Lonigan, killing him.{{sfn|Jones|1995|p=364}}{{Sfn|Macfarlane|2012|pp=70–73}} Ned said he did not begrudge his death, calling him the "meanest man that I had any account against".{{Sfn|FitzSimons|2013|p=191}} | |||

| The gang questioned McIntyre and took his and Lonigan's firearms.{{Sfn|Macfarlane|2012|pp=70–73}} Hoping to convince Ned to spare Kennedy and Scanlan, McIntyre informed him that they too were Irish Catholics. Ned replied, "I will let them see what one native can do."{{Sfn|McQuilton|1987|p=}}{{Page needed|date=December 2024}} At about 5.30 p.m., the gang heard them approaching and hid. Ned advised McIntyre to tell them to surrender. As the constable did so, the gang ordered them to bail up. Kennedy reached for his revolver, whereupon the gang fired. Scanlan dismounted and, according to McIntyre, was shot while trying to unsling his rifle. Ned maintained that Scanlan fired and was trying to fire again when he fatally shot him.{{Sfn|Macfarlane|2012|pp=70–73}}{{sfn|Jones|1995|p=136}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The Kelly gang questioned McIntyre and armed themselves with the policemen's shotgun and revolvers.{{Sfn|Macfarlane|2012|pp=70–73}} At about 5.30 p.m., Kennedy and Scanlan returned on horseback and the Kelly gang hid themselves. According to McIntyre, he walked towards Kennedy but before he could speak to him, the Kelly gang ordered the police to bail up. Kennedy tried to unclip his gun holster and shots were fired by the gang. McIntyre advised Kennedy to surrender as he was surrounded. Meanwhile, Scanlan dismounted and was shot while trying to unsling his rifle. McIntyre stated that Scanlan did not have time to fire a shot. According to Ned, Scanlan fired and Ned shot him as he tried to fire again. Scanlan died soon after.{{Sfn|Macfarlane|2012|pp=70–73}}<ref>Jones (1995). p. 136.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Kennedy had dismounted and, according to McIntyre, tried to surrender without firing a shot, but the gang continued firing at him. According to Kelly, Kennedy hid behind a tree and started firing. Kennedy retreated into the bush. Ned and Dan pursued him for almost a mile,{{Sfn|Morrissey|2015|p=87}} exchanging gunfire with the sergant, before Ned shot him in the right side. According to Ned, Kennedy then turned around to face him and Ned shot him in the chest with his shotgun, not realising that Kennedy had dropped his revolver and was turning to surrender.{{Sfn|Macfarlane|2012|pp=70–73}} | |||

| According to McIntyre, the gang continued firing at Kennedy as he dismounted and tried to surrender. Ned later stated that Kennedy hid behind a tree and fired back, then fled into the bush. Ned and Dan pursued and exchanged gunfire with the sergeant for over 1 km before Ned shot him in the right side.{{Sfn|Morrissey|2015|p=87}} According to Ned, Kennedy then turned to face him and Ned shot him in the chest with his shotgun, not realising that Kennedy had dropped his revolver and was trying to surrender.{{Sfn|Macfarlane|2012|pp=70–73}} | |||

| Amidst the shootout, McIntyre, still unarmed, escaped on Kennedy's horse.{{Sfn|Macfarlane|2012|pp=70–73}} He reached Mansfield the following day and a search party was quickly dispatched and found the bodies of Lonigan and Scanlan. Kennedy's body was found two days later.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|p=462}}{{Sfn|Macfarlane|2012|pp=76–77}} | |||

| In his accounts of the shootout, Ned justified the killings as acts of self-defence, citing reports of policemen boasting that they would shoot him on sight, the cache of weapons and ammunition that the police carried, and their failure to surrender as evidence of their intention to kill him.{{Sfn|Morrissey|2015|pp=216–28}} McIntyre stated that the police party's intention was to arrest him, that they were not excessively armed, and that it was the gang who were the aggressors.{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=132, 134}}{{Sfn|Morrissey|2015|p=69}} Jones, Morrissey and others have questioned aspects of both versions of events.{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=132–33}}{{Sfn|Morrissey|2015|pp=216–28}} | |||

| In the Jerilderie letter, Kelly claimed that he had been told that a number of police officers had boasted that they would shoot him without giving him a chance to surrender. He also claimed that the weapons (especially the two rifles) and amount of ammunition the police party carried indicated their intention of killing him rather than arresting him. He claimed that these circumstances, and the failure of the police to surrender when ordered to, justified him killing them in self-defence.{{Sfn|Morrissey|2015|pp=216–228}} McIntyre stated that he told Kelly that the intention of the police party was to arrest him and that they were not excessively armed in the circumstances. He stated that it was the Kelly gang who confronted the police with their weapons drawn and that they did not give the police a realistic chance to surrender.<ref>Jones (1995) pp. 132, 134.</ref>{{Sfn|Morrissey|2015|p=69}} | |||

| ===Outlawed under the ''Felons Apprehension Act''=== | ===Outlawed under the ''Felons Apprehension Act''=== | ||

| ] declaring Ned and Dan |

] declaring Ned and Dan outlaws]] | ||

| On 28 October, the Victorian government announced a reward of £800 for the arrest of the gang; it was soon increased to £2,000. Three days later, the ] passed the ''Felons Apprehension Act'', which came into effect on 1 November. The bushrangers were given until 12 November to surrender. On 15 November, having remained at large, they were officially outlawed. As a result, anyone who encountered them armed, or had a reasonable suspicion that they were armed, could kill them without consequence. The act also penalised anyone who gave "any aid, shelter or sustenance" to the outlaws or withheld information, or gave false information, to the authorities. Punishment was imprisonment with or without hard labour for up to 15 years.{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=144, 146, 159–60}} | |||

| The Victorian act was based on the ''Felons Apprehension Act'' |

The Victorian act was based on the 1865 ''Felons Apprehension Act'', passed by the ] to reign in bushrangers such as the ] and ]. In response to the Kelly gang, the New South Wales parliament re-enacted their legislation as the ''Felons Apprehension Act 1879''.<ref name=":12">{{Cite journal|last=Eburn|first=Michael|date=2005|title=Outlawry in Colonial Australia, the Felons Apprehension Acts 1865–1899|url=http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/ANZLawHisteJl/2005/6.pdf|journal=ANZLH e-Journal|volume=25|pages=80–93}}</ref> | ||

| ==Euroa raid== | ==Euroa raid== | ||

| ] |

] raid]] | ||

| After the police killings, the |

After the police killings, the gang tried to escape into New South Wales but, due to flooding of the ], were forced to return to north-eastern Victoria. They narrowly avoided the police on several occasions and relied on the support of an extensive network of sympathisers.{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=142–60}}{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=294–306}} | ||

| In need of |

In need of funds, the gang decided to rob the bank of ]. Byrne reconnoitered the small town on 8 December 1878. Around midday the next day, the gang held up Younghusband Station, outside Euroa. Fourteen male employees and passers-by were taken hostage and held overnight in an outbuilding on the station; female hostages were held in the homestead. A number of hostages were likely sympathisers of the gang and had prior knowledge of the raid.{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=161–64}} | ||

| The following day, Dan guarded the hostages while Ned, Byrne and Hart rode out to cut |

The following day, Dan guarded the hostages while Ned, Byrne and Hart rode out to cut Euroa's telegraph wires. They encountered and held up a hunting party and some railway workers, whom they took back to the station. Ned, Dan and Hart then went into Euroa, leaving Byrne to guard the prisoners.{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=165–67}} | ||

| Around 4 p.m., the three outlaws held up the Euroa branch of the ], netting cash and gold worth £2,260 and a small number of documents and securities.{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=167–68}} Fourteen staff members were taken back to Younghusband Station as hostages.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|p=320}} There the gang performed ] for the thirty-seven hostages, before leaving at about 8.30 p.m., warning their captives to stay put for three hours or suffer reprisals.{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=176–77}} | |||

| Following the raid, a number of newspapers commented on the efficiency of its execution and compared it with the inefficiency of the police |

Following the raid, a number of newspapers commented on the efficiency of its execution and compared it with the inefficiency of the police. Several hostages stated that the gang had behaved courteously and without violence during the raid.{{sfn|Jones|1995|p=172}} However, hostages also stated that on several occasions the bushrangers threatened to shoot them and burn buildings containing hostages if there was any resistance.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=311–15, 324, 330–31}} | ||

| === Cameron Letter === | === Cameron Letter === | ||

| At Younghusband Station, Byrne wrote two copies of a letter that Kelly had dictated. They were posted on 14 December to Donald Cameron, a Victorian parliamentarian who Kelly mistook as sympathetic to the gang, and Superintendent John Sadleir. In the letter, Kelly gives his version of the Fitzpatrick incident and the Stringybark Creek killings, and describes cases of alleged police corruption and harassment of his family, signing off as "Edward Kelly, enforced outlaw". He expected Cameron to read it out in parliament, but the government only allowed summaries to be made public. '']'' called it the work of "a clever illiterate".{{Sfn|Jones|1992|pp=88–89, 216}} Premier ], a vociferous critic of the gang, also found it "very clever", and alerted railway authorities to an allusion Kelly makes to tearing up tracks. Kelly expanded on much of its content in the ] of 1879.{{Sfn|Corfield|2003|pp=91–95}} | |||

| ==Kelly sympathisers |

==Kelly sympathisers detained== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| On 2 January 1879, police |

On 2 January 1879, police obtained warrants for the arrest of 30 presumed Kelly sympathisers, 23 of whom were remanded in custody.{{Sfn|McQuilton|1987|p=114}} Over a third were released within seven weeks due to lack of evidence, but nine sympathisers had their remand renewed on a weekly basis for almost three months, despite the police failing to produce evidence for a committal hearing. In a letter to Acting Chief Secretary ], Kelly accused the government of "committing a manifest injustice in imprisoning so many innocent people" and threatened reprisals. Police claimed that such threats dissuaded their informants from giving sworn evidence.{{Sfn|Dawson|2018|pp=12, 20–21}} | ||

| On 22 April, |

On 22 April, police magistrate Foster refused prosecution requests to continue remands and discharged the remaining detainees. Although the police command opposed this decision, by then it was clear that the tactic of detaining sympathisers had not impeded the gang.{{Sfn|Dawson|2018|p=21}} | ||

| Jones argues that the |

Jones argues that the detention strategy swung public sympathy away from the police.{{sfn|Jones|1995|p=178}} Dawson, however, points out that while there was widespread condemnation of the denial of the civil liberties of those detained, this did not necessarily mean support for the outlaws grew.{{Sfn|Dawson|2018|pp=21–22}} | ||

| ==Jerilderie raid== | ==Jerilderie raid== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Following the Euroa raid, |

Following the Euroa raid, the reward for Kelly's capture increased to £1,000. Fifty-eight police were transferred to north-eastern Victoria, totaling 217 in the district. Around 50 soldiers were also deployed to guard local banks. The gang distributed most proceeds from the raid to family and other sympathisers. Once more in need of funds, they planned to rob the bank at ], a town 65 km across the border in New South Wales. A number of sympathisers moved into Jerilderie before the raid to provide undercover support.{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=173–74, 179–80}}{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=326–28, 334, 338}} | ||

| On |

On 7 February 1879, the gang crossed the Murray River between ] and ] and camped overnight in the bush. The following day they visited a hotel about 3 km from Jerilderie, where they drank and chatted with patrons and staff, learning more about the town and its police presence.{{sfn|Jones|1995|p=182}} | ||

| In the early hours of 9 February, the gang bailed up the Jerilderie police barracks and secured in the lockup the two constables present, George Devine and Henry Richards. They also held Devine's wife and young children hostage overnight.{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=181–82}} The following afternoon, Byrne and Hart, dressed as police, went out with Richards to familiarise themselves with the town.{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=183–85}} | |||

| At 10 am on 10 February, Ned and Byrne donned police uniforms and took Richards with them into town, leaving Devine in the lockup and warning his wife that they would kill her and her children if she left the barracks.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|p=346}} The gang held up the Royal Mail Hotel and, while Dan and Hart controlled the hostages, Ned and Byrne robbed the neighbouring ] of £2,141 in cash and valuables.{{sfn|Jones|1995|p=186}} Ned also found and burnt deeds, mortgages and securities, saying "the bloody banks are crushing the life's blood out of the poor, struggling man".{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=347–49}} | |||

| The Kelly gang spent most of Sunday morning preparing for the bank robbery while many of the town's population were attending church. In the afternoon, Byrne and Hart, dressed in police uniforms, took the disarmed Constable Richards with them into town so they could familiarise themselves with its layout. Richards was told to introduce the strangers as police reinforcements sent to search for the Kelly gang. The three then returned to the police barracks and the gang finalised plans for the following day's raid.<ref>Jones (1995). pp. 183–85.</ref> | |||

| With hostages from the bank now detained in the hotel, Byrne held up the post office and smashed its telegraph system while Ned had several hostages cut down telegraph wires. After lecturing the 30 or so hostages on police corruption and the justice system, Ned freed them, except for Richards and two telegraphists, who he had secured in the lockup.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=352–56}} Dan and Byrne then left town with the police's horses and weapons. Ned stayed a while longer to ] a group of sympathisers at the Albion Hotel. While there, he forced Hart to return a watch he had stolen from priest ], who also persuaded Ned to leave a racehorse he had taken as it belonged to "a young lady".{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=356–62}} After the raid, the gang went into hiding for 17 months.{{sfn|Jones|1995|p=194}} | |||

| At 10 a.m. on 10 February, Kelly and Byrne donned police uniforms and the four outlaws took Richards with them into town. They had left Devine in the police lockup and had warned Mrs Devine that if she tried to leave the barracks they would burn it down with her and the children inside.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|p=346}} | |||

| The gang went into the main street of Jerilderie and held up the Royal Mail Hotel, which was next door to the Bank of New South Wales. They took the hotel staff and patrons hostage and, as the raid progressed, anyone walking into the hotel was captured and held in the hotel's parlour. It is almost certain that some of those held were sympathisers planted by the outlaws. Ned and Byrne then entered the bank from the rear, leaving Dan and Hart in control of the hotel.<ref>Jones (1995). p. 186.</ref> Ned and Byrne held up the bank, taking £2,141 in cash as well as jewellery and other valuables. Ned also took deeds, mortgages and securities from the safe which he later had burned because "the bloody banks are crushing the life's blood out of the poor, struggling man". The bank staff and several patrons were taken prisoner and transferred to the parlour of the hotel.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=347–49}} | |||

| Byrne then held up the post office and destroyed the ] and insulator. Following this, several of the prisoners were ordered to take axes and bring down the telegraph poles and wires. Once the telegraph was cut, Ned went with two hostages to the newspaper owner's home where he asked for copies of his Jerilderie letter to be printed. The newspaper owner, however, had earlier escaped capture at the bank and fled the town. | |||

| After a detour to appraise a locally famous race horse, Ned returned to the hotel and delivered a speech to the hostages outlining his grievances against the police and the justice system. He then told the hostages, who now numbered about thirty, that they were free to go. However, he took Richards and the two post office workers (who knew how to operate the telegraph) with him to the police barracks.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=352–56}} | |||

| Back at the barracks, the gang secured the two policemen and two post office workers in the lockup and prepared to leave with the proceeds from the bank robbery, the police horses and police weapons. Mrs Devine was threatened with reprisals if she released the prisoners before 7.30 p.m. Dan and Byrne then rode out of Jerilderie. Ned and Hart rode back into town where Ned stayed a short while, drinking at the Albion (Traveller's Rest) Hotel with the strangers who had recently entered the town and were soon to leave. While there, the local parson, ], persuaded Ned to leave the race horse he had taken as it belonged to "a young lady".{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=356–62}} When Kelly and Hart left, they were not seen again by the police for 17 months.<ref>Jones (1995). p. 194.</ref> | |||

| ===Jerilderie Letter=== | ===Jerilderie Letter=== | ||

| Line 222: | Line 174: | ||

| {{Blockquote|text=I wish to acquaint you with some of the occurrences of the present past and future.|sign=Opening line of the Jerilderie Letter<ref name=conv/>}} | {{Blockquote|text=I wish to acquaint you with some of the occurrences of the present past and future.|sign=Opening line of the Jerilderie Letter<ref name=conv/>}} | ||

| {{Wikisource|The Jerilderie Letter}} | {{Wikisource|The Jerilderie Letter}} | ||

| ]]] | ]]] | ||

| Prior to arriving in Jerilderie, Kelly composed a lengthy letter with the aim of tracing his path to outlawry, justifying his actions, and outlining the alleged injustices he and his family suffered at the hands of the police. He also |

Prior to arriving in Jerilderie, Kelly composed a lengthy letter with the aim of tracing his path to outlawry, justifying his actions, and outlining the alleged injustices he and his family suffered at the hands of the police. He also implores ] to share their wealth with the rural poor, invokes a history of Irish rebellion against the English, and threatens to carry out a "colonial stratagem" designed to shock not only Victoria and its police "but also the whole British army".{{sfn|Jones|2010|pp=184–85}}<ref name="gelderweaver">Gelder, Ken; Weaver, Rachael (2017). ''Colonial Australian Fiction: Character Types, Social Formations and the Colonial Economy''. ]. {{ISBN|978-1-74332-461-5}}, pp. 57–58.</ref> Dictated to Byrne, the Jerilderie Letter, a handwritten document of fifty-six pages and 7,391 words, was described by Kelly as "a bit of my life". He tasked Edwin Living, a local bank accountant, with delivering it to the editor of the '']'' for publication.{{sfn|Molony|2001|pp=136–37}} Due to political suppression, only excerpts were published in the press, based on a copy transcribed by John Hanlon, owner of the Eight Mile Hotel in ]. The letter was rediscovered and published in full in 1930.<ref name=gelderweaver/> | ||

| According to historian Alex McDermott, "Kelly inserts himself into history, on his own terms, with his own voice. ... We hear the living speaker in a way that no other document in our history achieves".{{sfn|Kelly|2012|p=xxviii}} It has been interpreted as a proto-] manifesto;<ref name="barkham">Barkham, Patrick (4 December 2000). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180519204735/https://www.theguardian.com/world/2000/dec/04/worlddispatch.patrickbarkham |date=19 May 2018 }}. ''The Guardian''. Retrieved 19 May 2018.</ref> one eyewitness to the Jerilderie raid noted that the letter suggested Kelly would "have liked to have been at the head of a hundred followers or so to upset the existing government".<ref>. '']''. 2 January 1914. p. 1. Retrieved 10 January 2024.</ref>{{sfn|Jones|2010|pp=371–72}} It has also been described as a "murderous, ... maniacal rant",<ref name="farrell">Farrell, Michael (2015). ''Writing Australian Unsettlement: Modes of Poetic Invention, 1796–1945''. Springer. {{ISBN|978-1-137-46541-2}}, p. 17.</ref> and "a remarkable insight into Kelly's grandiosity".<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=MacFarlane |first1=Ian |last2=Scott |first2=Russ |date=2014 |title=Ned Kelly – Stock Thief, Bank Robber, Murderer – Psychopath |journal=Psychiatry, Psychology and Law |volume=21 |issue=5 |pages=716–746 |doi=10.1080/13218719.2014.908483}}.</ref> Noted for its unorthodox grammar, the letter reaches "delirious poetics",<ref name="gelderweaver" /> Kelly's language being "hyperbolic, allusive, hallucinatory ... full of striking metaphors and images".<ref name="conv">Gelder, Ken (5 May 2014). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150402141310/http://theconversation.com/the-case-for-ned-kellys-jerilderie-letter-25898 |date=2 April 2015 }}, '']''. Retrieved 20 March 2015.</ref> His invective and sense of humour are also present; in one well-known passage, he calls the Victorian police "a parcel of big ugly fat-necked ] headed, big bellied, ] legged, narrow hipped, splaw-footed sons of Irish bailiffs or English landlords".<ref>Woodcock, Bruce (2003). ''Peter Carey''. Manchester University Press. {{ISBN|978-0-7190-6798-3}}, p. 139.</ref> The letter closes: | |||

| {{blockquote|neglect this and abide by the consequences, which shall be worse than the rust in the wheat of Victoria or the druth of a dry season to the grasshoppers in New South Wales I do not wish to give the order full force without giving timely warning. but I am a widows son outlawed and my orders <u>must</u> be obeyed.{{sfn|Seal|2002|p=88}}}} | |||

| According to historian Alex McDermott, "Kelly inserts himself into history, on his own terms, with his own voice. ... We hear the living speaker in a way that no other document in our history achieves".{{sfn|Kelly|2012|p=xxviii}} It has been interpreted as a proto-republican manifesto;<ref name="barkham">Barkham, Patrick (4 December 2000). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180519204735/https://www.theguardian.com/world/2000/dec/04/worlddispatch.patrickbarkham |date=19 May 2018 }}. ''The Guardian''. Retrieved 19 May 2018.</ref> for others, it is a "murderous, ... maniacal rant",<ref name="farrell">Farrell, Michael (2015). ''Writing Australian Unsettlement: Modes of Poetic Invention, 1796–1945''. Springer. {{ISBN|978-1-137-46541-2}}, p. 17.</ref> and "a remarkable insight into Kelly's grandiosity".<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=MacFarlane |first1=Ian |last2=Scott |first2=Russ |date=2014 |title=Ned Kelly – Stock Thief, Bank Robber, Murderer – Psychopath |journal=Psychiatry, Psychology and Law |volume=21 |issue=5}}.</ref> Noted for its unorthodox grammar, the letter reaches "delirious poetics",<ref name="gelderweaver" /> Kelly's language being "hyperbolic, allusive, hallucinatory ... full of striking metaphors and images".<ref name="conv">Gelder, Ken (5 May 2014). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150402141310/http://theconversation.com/the-case-for-ned-kellys-jerilderie-letter-25898 |date=2 April 2015 }}, '']''. Retrieved 20 March 2015.</ref> His invective and sense of humour are also present; in one well-known passage, he calls the Victorian police "a parcel of big ugly fat-necked ] headed, big bellied, magpie legged, narrow hipped, splaw-footed sons of Irish bailiffs or English landlords".<ref>Woodcock, Bruce (2003). ''Peter Carey''. Manchester University Press. {{ISBN|978-0-7190-6798-3}}, p. 139.</ref> The letter closes:{{sfn|Seal|2002|p=88}} | |||

| {{blockquote|neglect this and abide by the consequences, which shall be worse than the rust in the wheat of Victoria or the druth of a dry season to the grasshoppers in New South Wales I do not wish to give the order full force without giving timely warning. but I am a widows son outlawed and my orders <u>must</u> be obeyed.}} | |||

| ==Reward increase and disappearance== | ==Reward increase and disappearance== | ||

| ] ] | ] | ||

| In response to the Jerilderie raid, the New South Wales government and several banks collectively issued £4,000 for the gang's capture, dead or alive, the largest reward offered in the colony since £5,000 was placed on the heads of the outlawed ] in 1867.<ref>Smith, Peter. C.. (2015). ''The Clarke Gang: Outlawed, Outcast and Forgotten''. Rosenberg Publishing, {{ISBN|978-1-925078-66-4}}, endnotes.</ref> The Victorian government matched the offer for the Kelly gang, bringing the total amount to £8,000, bushranging's largest-ever reward.{{sfn|Kenneally|1929|p=105}} | In response to the Jerilderie raid, the New South Wales government and several banks collectively issued £4,000 for the gang's capture, dead or alive, the largest reward offered in the colony since £5,000 was placed on the heads of the outlawed ] in 1867.<ref>Smith, Peter. C.. (2015). ''The Clarke Gang: Outlawed, Outcast and Forgotten''. Rosenberg Publishing, {{ISBN|978-1-925078-66-4}}, endnotes.</ref> The Victorian government matched the offer for the Kelly gang, bringing the total amount to £8,000, bushranging's largest-ever reward.{{sfn|Kenneally|1929|p=105}} | ||

| The Victorian police continued to receive many reports of sightings of the outlaws |

The Victorian police continued to receive many reports of sightings of the outlaws and information about their activities from their network of informants. Chief Commissioner of Police ] and Superintendent ] directed operations against the gang from Benalla. Hare organised frequent search parties and surveillance of Kelly sympathisers.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=368–78}}{{Sfn|McQuilton|1987|pp=121–23}} | ||

| ] unit, sent from Queensland to Victoria in 1879 to help capture the gang|left]] | ] unit, sent from Queensland to Victoria in 1879 to help capture the gang|left]] | ||

| In March 1879, six Queensland ] troopers and a senior constable under the command of sub-Inspector Stanhope O'Connor were deployed to Benalla to join the hunt for the |

In March 1879, six Queensland ] troopers and a senior constable under the command of sub-Inspector Stanhope O'Connor were deployed to Benalla to join the hunt for the gang. Although Kelly feared the ] ability of the Aboriginal troopers, Standish and Hare doubted their value and temporarily withdrew their services.{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=226, 243–44}}{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=203–04, 222}} | ||

| In May 1879, on the advice of Standish, the ] blacklisted 86 alleged Kelly sympathisers from buying land in the secluded areas of northeastern Victoria. The aim of the policy was to disperse the gang's network of sympathisers and disrupt stock theft in the region. Jones and others claim that it caused widespread resentment and hardened support for the outlaws.{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=207–10}} Morrissey, however, states that although the policy was sometimes used unfairly, it was effective and supported by the majority of the community.{{Sfn|Morrissey|2015|pp=151–52}} | |||

| ] | |||

| On 3 July 1879, following media and parliamentary criticism of the cost and lack of success of the Kelly gang search, Standish appointed Assistant Commissioner Charles Nicolson in charge of operations at Benalla in place of the injured Hare. Standish removed fourteen troopers and seventeen foot police from Nicolson's command, withdrew most of the soldiers guarding banks, and cut the budget for the search. Nicolson responded by cutting back search parties and relying more heavily on targeted surveillance and his network of spies and informers.<ref>Jones (1995). pp. 208–09.</ref> | |||

| Facing media and parliamentary criticism over the costly and failed gang search, Standish appointed Assistant Commissioner ] as leader of operations at Benalla on 3 July 1879. Standish reduced Nicolson's police forces, withdrew most of the soldiers guarding banks, and cut the search budget. Nicolson relied more heavily on targeted surveillance and his network of spies and informers.{{sfn|Jones|1995|pp=208–09}} | |||

| After almost a year of unsuccessful efforts to capture the outlaws, Nicolson was replaced by Hare. In June 1880, police informant Daniel Kennedy reported that the gang were planning another raid and had made bullet-proof armour out of agricultural equipment. Hare dismissed the latter as preposterous and sacked Kennedy.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=384–86}}{{sfn|Jones|1995|p=226}} | |||

| ==Glenrowan affair== | ==Glenrowan affair== | ||

| ===Murder of Aaron Sherritt=== | ===Murder of Aaron Sherritt=== | ||

| {{Blockquote|text=... I look upon Ned Kelly as an extraordinary man; there is no man in the world like him, he is superhuman.|sign=Aaron Sherritt to Superintendent Hare{{sfn|Jones|2010|p=}}}} | {{Blockquote|text=... I look upon Ned Kelly as an extraordinary man; there is no man in the world like him, he is superhuman.|sign=] to Superintendent ]{{sfn|Jones|2010|p=}}}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| During the Kelly outbreak, police watch parties monitored |

During the Kelly outbreak, police watch parties monitored Byrne's mother's house in the Woolshed Valley near ]. The police used the house of her neighbour, ], as a base of operations and kept watch from nearby caves at night. Sherritt, a former Greta Mob member and lifelong friend of Byrne, accepted police payments for camping with the watch parties and for informing on the gang.{{sfn|Jones|2010|p=}}{{page needed|date=December 2024}} Detective ] doubted Sherritt's value as an informer, suspecting he lied to the police to protect Byrne.{{sfn|Kelson|McQuilton|2001|p=128}}{{sfn|Jones|1995|p=205}} | ||

| In March 1879 Byrne's mother |

In March 1879 Byrne's mother saw Sherritt with a police watch party and later publicly denounced him as a spy.{{Sfn|McQuilton|1987|p=122}}{{sfn|Jones|1995|p=206}} In the following months, Byrne and Ned sent invitations to Sherritt to join the gang, but when he continued his relationship with the police, the outlaws decided to murder him as a means to launch a grander plot, one that they boasted would "astonish not only the Australian colonies but the whole world".{{sfn|Farwell|1970|p=193}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| On 26 June 1880, Dan and Byrne rode into the Woolshed Valley. That evening, they kidnapped |

On 26 June 1880, Dan and Byrne rode into the Woolshed Valley. That evening, they kidnapped a local gardener, Anton Wick, and took him to Sherritt's hut, which was occupied by Sherritt, his pregnant wife Ellen and her mother, and a four-man police watch party.{{Sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=390–92}} | ||

| Byrne forced Wick to knock on the back door and call out for Sherritt. When Sherritt answered the door, Byrne shot him in the throat and chest with a shotgun, killing him. Byrne and Dan then entered the hut while the policemen hid in one of the bedrooms. Byrne overheard them scrambling for their shotguns and demanded that they come out. When they did not respond he fired into the bedroom. He then sent Ellen into the bedroom to bring the police out, but they detained her in the room.<ref name=":7">Jones (1995). pp. 230–31.</ref> | |||

| The outlaws left the hut |

The outlaws left the hut, collected kindling, and loudly threatened to burn alive those inside. They stayed outside for approximately two hours, yelled more threats, then released Wick and rode away.{{sfn|Kieza|2017|pp=392–93}}{{Sfn|Morrissey|2015|pp=122–23}} | ||

| ===Plot to wreck the police train and attack Benalla=== | |||

| The police did not leave the hut until the following morning, for fear that the bushrangers would be still waiting outside for them. News of Sherritt's death only reached Hare in Benalla at 2.30 p.m. on Sunday, 27 June.{{Sfn|McQuilton|1987|pp=156–57}} | |||

| ] in a plot to derail the police special train]] | |||

| The gang estimated that the policemen at Sherritt's would report his murder to Beechworth within a few hours, prompting a police special train to be sent up from Melbourne. They also surmised that the train would collect reinforcements in ] before continuing through ], a small town in the ]. There, the gang planned to derail the train and shoot dead any survivors, then ride to an unpoliced Benalla where they would bomb the railway bridge over the ], thereby isolating the town and giving them time to rob the banks, bomb the police barracks, torch the courthouse, free the gaol's prisoners, and generally sow chaos before returning to the bush.{{sfn|Innes|2008|p=105}}{{sfn|Dawson|2018|pp=57–58}} | |||

| While Byrne and Dan were in the Woolshed Valley, Ned and Hart forced two railway workers camped at Glenrowan to damage the track. The outlaws selected a sharp curve at an incline, where the train would be speeding at 60 mph before derailing into a deep gully. They told their captives they were going to "send the train and its occupants to hell".{{sfn|McMenomy|1984|p=152}}{{Sfn|McQuilton|1987|p=156}} | |||

| ===Siege and shootout=== | |||

| ] in a plot to derail the Police Special Train]] | |||

| The gang estimated that the policemen inside Sherritt's hut would relay news of his murder to Beechworth by early Sunday morning, prompting a special police train to be sent up from Melbourne. They also surmised that the train would collect reinforcements in Benalla before continuing through ], a small town in the ]. There, the gang planned to derail the train and shoot dead any survivors, then ride to an unpoliced Benalla where they would rob the banks, set fire to the courthouse, blow up the police barracks, release anyone imprisoned in the gaol, and "generally play havoc with the entire town" before returning to the bush.{{sfn|Dawson|2018|pp=57–58}} | |||

| The bushrangers took over the ], the stationmaster's home and Ann Jones' Glenrowan Inn, opposite the station. They used the hotel to hold the workers, passers-by, and other men; most of the women and children taken prisoner were held at the stationmaster's home. The other hotel in town, McDonnell's Railway Hotel, was used to stable the gang's stolen horses, one of which carried a keg of blasting powder and fuses.{{sfn|Jones|1995|p=205}} The packhorses also carried ], each made from stolen ] and weighing about {{convert|44|kg}}. Kelly conceived of the armour to protect the outlaws in shootouts with the police and planned to wear it when inspecting the train wreckage for survivors.{{Sfn|Morrissey|2015|p=121}} | |||