| Revision as of 07:11, 24 March 2014 view sourceHMSSolent (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers23,734 editsm Reverted 1 edit by 101.161.243.27 identified as test/vandalism using STiki← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:55, 9 January 2025 view source TG-article (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,543 edits Changing short description from "Capital and largest city of France" to "Capital and most populous city of France"Tag: Shortdesc helper | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|Capital and most populous city of France}} | ||

| {{About|the capital city of France}} | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Parisien}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2013}} | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=May 2013}} | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| {{EngvarB|date=July 2018}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=August 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox French commune | {{Infobox French commune | ||

| |name = Paris | |name = Paris | ||

| |commune status = ], ] and ] | |||

| |image = <imagemap> | |||

| |image = {{multiple image | |||

| File:Paris montage2.jpg|275px|alt=Paris montage. Clicking on an image in the picture causes the browser to load the appropriate article. | |||

| |border = infobox | |||

| rect 0 0 1200 441 ] | |||

| |perrow = 1/3/2/1 | |||

| rect 0 1260 618 1398 ] | |||

| |total_width = 290 | |||

| rect 0 447 618 1398 ] | |||

| |caption_align = center | |||

| rect 618 447 1200 1056 ] | |||

| |image1 = La Tour Eiffel vue de la Tour Saint-Jacques, Paris août 2014 (2).jpg | |||

| rect 618 1056 1200 1398 ] | |||

| |caption1 = ] and the ] from ] | |||

| rect 21 1521 117 1632 ] | |||

| |image2 = Notre-Dame de Paris 2013-07-24.jpg | |||

| rect 120 1521 165 1632 ] | |||

| |caption2 = ] | |||

| rect 369 1494 412 1575 ] | |||

| |image3 = Basilique du Sacré-Cœur de Montmartre, Paris 18e 140223 2.jpg | |||

| rect 456 1512 540 1569 ] | |||

| |caption3 = ] | |||

| rect 750 1524 1200 1680 ] | |||

| |image4 = Facade of the Panthéon, Paris 24 January 2016.jpg | |||

| rect 0 1635 600 1650 ] | |||

| |caption4 = ] | |||

| rect 0 1650 750 1680 ] | |||

| |image5 = Arc de Triomphe HDR 2007.jpg | |||

| rect 0 1395 1200 1695 ] | |||

| |caption5 = ] | |||

| rect 0 1395 1200 1803 ] | |||

| |image6 = Louvre Courtyard, Looking West.jpg | |||

| </imagemap> | |||

| |caption6 = The ] | |||

| |caption =Clockwise: Pyramid of the ], ], Looking towards ], Skyline of Paris on the ] river with the ] bridge, and the ] - clickable image | |||

| |image flag = Flag of Paris.svg | |||

| |image flag size = 100px | |||

| |image coat of arms = Grandes Armes de Paris.svg | |||

| |image coat of arms size = 120px | |||

| |flag legend = ] | |||

| |coat of arms legend = ] | |||

| |city motto = '']''<br />(Latin: "It is tossed by the waves, but does not sink") | |||

| |latitude = 48.8567 | |||

| |longitude = 2.3508 | |||

| |time zone = ] <small>(UTC +1)</small> | |||

| |mayor = ] | |||

| |party = ] | |||

| |term = 2008–14 | |||

| |subdivisions entry = ] | |||

| |subdivisions = ] | |||

| |area km2 = 105.4 | |||

| |area footnotes =<ref name="area">, including ] and ].</ref> | |||

| |INSEE=75056 | |||

| |postal code=75001-75020, 75116 | |||

| |un_locode = FRPAR | |||

| |population = 2243833 | |||

| |population date = 2010<ref name="paris_pop_2010">{{Fr icon}} {{cite web|url=http://www.insee.fr/fr/themes/tableau_local.asp?ref_id=POP&millesime=2010&nivgeo=COM&codgeo=75056|title=Chiffres clés évolution et structure de la population - Commune de Paris (75056)|author=]|accessdate=7 July 2013}}</ref> | |||

| |population ranking = ] | |||

| |urban area km2 = 2844.8 | |||

| |urban area date = 2010 | |||

| |urban pop = 10,413,386<ref name="paris_UU10_pop">{{cite web|url=http://www.recensement.insee.fr/chiffresCles.action?codeMessage=5&plusieursReponses=true&zoneSearchField=PARIS&codeZone=00851-UU2010&idTheme=3&rechercher=Rechercher|title=Unité urbaine 2010 : Paris (00851)|publisher=INSEE|language=French|accessdate=3 July 2012}}</ref> | |||

| |urban pop date = Jan. 2009 | |||

| |metro area km2 = 17174.4 | |||

| |metro area date = 2010 | |||

| |metro area pop = 12,161,542<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.recensement.insee.fr/chiffresCles.action?codeMessage=5&plusieursReponses=true&zoneSearchField=PARIS&codeZone=001-AU2010&idTheme=3&rechercher=Rechercher|title=Aire urbaine 2010 : Paris (001)|publisher=INSEE|accessdate=21 October 2011}}</ref><ref name="paris_AU10_pop">{{cite web|url=http://www.recensement.insee.fr/chiffresCles.action?zoneSearchField=PARIS&codeZone=001-AU2010&idTheme=3|title=Aire urbaine 2010 : Paris (001)|publisher=INSEE|language=French|accessdate=3 July 2012}}</ref> | |||

| |metro area pop date = Jan. 2009 | |||

| |website = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| |image coat of arms = Grandes Armes de Paris.svg | |||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| |image flag = Flag of Paris with coat of arms.svg | |||

| '''Paris''' ({{IPAc-en|lang|ˈ|p|ær|ɪ|s|}}, {{IPAc-en|ˈ|p|ɛər|ɪ|s|audio=En-us-Paris.ogg}}; {{IPA-fr|paʁi|lang|Paris1.ogg}}) is the capital and most populous city of ]. It is situated on the ] River, in the north of the country, at the heart of the ] ]. Within its administrative limits (the 20 ]), the city had 2,234,105 inhabitants in 2009 while its ] is ] with more than 12 million inhabitants. | |||

| |city motto = {{lang|la|]}}<br />"Tossed by the waves but never sunk" | |||

| |arrondissement = None | |||

| |canton = | |||

| |subdivisions entry = ] | |||

| |subdivisions = 20 ] | |||

| |INSEE = 75056 | |||

| |postal code = 75001-75020, 75116 | |||

| |demonym = Parisian(s) (]) ''Parisien(s)'' (masc.), ''Parisienne(s)'' (fem.) (]), ''Parigot(s)'' (masc.), "Parigote(s)" (fem.) (fr, colloquial) | |||

| |mayor = ]<ref>{{cite web |title=Répertoire national des élus: les maires |url=https://static.data.gouv.fr/resources/repertoire-national-des-elus-1/20221216-172042/rne-maire.csv |publisher=data.gouv.fr, Plateforme ouverte des données publiques françaises |date=16 December 2022 |language=fr |archive-date=27 February 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230227222303/https://static.data.gouv.fr/resources/repertoire-national-des-elus-1/20221216-172042/rne-maire.csv |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| |term = 2020–2026 | |||

| |party = ] | |||

| |intercommunality = ] | |||

| |coordinates = {{WikidataCoord|Q90|type:city(2,100,000)_region:FR-75C|display=it}} | |||

| |elevation m = 78 | |||

| |elevation min m = 28 | |||

| |elevation max m = 131 | |||

| |area km2 = 105.4 | |||

| |population = 2102650 | |||

| |population date = 2023 | |||

| |population footnotes = <ref name=pop2023/> | |||

| |urban area km2 = 2853.5 | |||

| |urban area date = 2020 | |||

| |urban pop = 10858852 | |||

| |urban pop date = 2019<ref name="paris_UU20_pop">{{cite web |url=https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/1405599?geo=UU2020-00851 |title=Comparateur de territoire: Unité urbaine 2020 de Paris (00851) |publisher=INSEE |language=French |access-date=10 February 2021 |archive-date=19 January 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210119110723/https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/1405599?geo=UU2020-00851 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |metro area km2 = 18940.7 | |||

| |metro area date = 2020 | |||

| |metro area pop = 13024518 | |||

| |metro area pop date = Jan. 2017<ref name="paris_AAV20_pop">{{cite web |url=https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/1405599?geo=AAV2020-001 |title=Comparateur de territoire: Aire d'attraction des villes 2020 de Paris (001) |publisher=INSEE |access-date=10 February 2021 |archive-date=20 January 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210120182725/https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/1405599?geo=AAV2020-001 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |website = {{URL|https://paris.fr}} | |||

| |population ranking=] in Europe<br/>] in France|map=Paris-Position.svg|map caption=Paris in France}} | |||

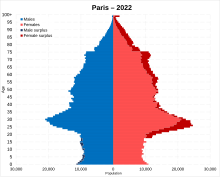

| '''Paris''' ({{IPA|fr|paʁi|audio=Paris Pronunciation in French by James Tamim.ogg}})<!--Do not add English pronunciation per MOS:LEAD.--> is the ] and ] of ]. With an estimated population of 2,102,650 residents in January 2023<ref name=pop2023/> in an area of more than {{convert|105|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}},<ref name="pop2019">{{cite web |url=https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/6005800?geo=COM-75056 |title=Populations légales 2019: Commune de Paris (75056) |date=29 December 2021 |publisher=INSEE |access-date=3 February 2022 |archive-date=22 January 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220122150105/https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/6005800?geo=COM-75056 |url-status=live}}</ref> Paris is the ] in the ], the ] in ] and the ] in 2022.<ref>{{Cite web |date=4 October 2020 |title=The World's Most Densely Populated Cities |url=https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-world-s-most-densely-populated-cities.html |access-date=4 March 2022 |website=WorldAtlas |archive-date=19 March 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220319082523/https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-world-s-most-densely-populated-cities.html |url-status=live}}</ref> Since the 17th century, Paris has been one of the world's major centres of ], ], ], ], ], and ]. Because of its leading role in the ] and ] and its early adaptation of extensive street lighting, it became known as the City of Light in the 19th century.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Paris |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Paris |access-date=8 August 2022 |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |archive-date=27 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220827145809/https://www.britannica.com/place/Paris |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The City of Paris is the centre of the ] region, or Paris Region, with an official estimated population of 12,271,794 inhabitants in January 2023, or about 19% of the population of France.<ref name=pop2023/> The Paris Region had a nominal ] of €765 billion (US$1.064 trillion when adjusted for ])<ref>{{cite web |author=Source: PPPs and exchange rates |url=https://data.oecd.org/conversion/purchasing-power-parities-ppp.htm |title=Conversion rates – Purchasing power parities (PPP) – OECD Data |publisher=Data.oecd.org |date= |accessdate=9 March 2022 |archive-date=4 November 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171104144219/https://data.oecd.org/conversion/purchasing-power-parities-ppp.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> in 2021, the highest in the European Union.<ref>{{Cite web |date=10 March 2023 |title=Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by metropolitan regions |url=https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/MET_10R_3GDP/default/table?lang=en |access-date=13 June 2023 |website=ec.europa.eu |archive-date=15 February 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230215185052/https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/met_10r_3gdp/default/table?lang=en |url-status=live }}</ref> According to the ] Worldwide Cost of Living Survey, in 2022, Paris was the city with the ninth-highest cost of living in the world.<ref>{{Cite news |title=The world's most, and least, expensive cities |newspaper=The Economist |url=https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2022/11/30/the-worlds-most-and-least-expensive-cities |access-date=1 December 2022 |issn=0013-0613 |archive-date=1 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221201044121/https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2022/11/30/the-worlds-most-and-least-expensive-cities |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| An important settlement for more than two millennia, by the late 12th century Paris had become a walled ] city that was one of Europe's foremost centres of learning and the arts and the largest city in the Western world until the turn of the 18th century. Paris was the focal point for many important political events throughout its history, including the ]. Today it is one of the world's leading business and cultural centres, and its influence in politics, education, entertainment, media, science, fashion and the arts all contribute to its status as one of the world's major ]. The city has one of the ], €607 billion (US$845 billion) as of 2011, and as a result of its high concentration of national and international political, cultural and scientific institutions is one of the world's leading tourist destinations. The Paris Region hosts the world headquarters of 30 of the ] companies<ref name="fortune500">{{cite news|url=http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/global500/2012/countries/France.html?iid=smlrr|title=Global Fortune 500 by countries: France|author=]|accessdate=2013-08-16}}</ref> in several business districts, notably ], the largest dedicated business district in Europe.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.metropolitiques.eu/La-Defense-the-Planning-and.html|title=La Défense: the Planning and Politics of a Global Business District|author=metropolitics.eu|accessdate=2013-08-16}}</ref> | |||

| Paris is a major railway, highway, and air-transport hub served by two international airports: ], the ], and ].<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.usatoday.com/story/travel/flights/todayinthesky/2018/04/09/list-worlds-20-busiest-airports-2017/498552002/ |title=List: The world's 20 busiest airports (2017) |work=USA Today |access-date=2 May 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180625213204/https://www.usatoday.com/story/travel/flights/todayinthesky/2018/04/09/list-worlds-20-busiest-airports-2017/498552002/ |archive-date=25 June 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |url=http://www.airport-world.com/news/general-news/6601-aci-figures-reveal-the-world-s-busiest-passenger-and-cargo-airports.html |title=ACI reveals the world's busiest passenger and cargo airports |date=9 April 2018 |work=Airport World |access-date=2 May 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180628125151/http://www.airport-world.com/news/general-news/6601-aci-figures-reveal-the-world-s-busiest-passenger-and-cargo-airports.html |archive-date=28 June 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref> Opened in 1900, the city's subway system, the ], serves 5.23{{nbsp}}million passengers daily.<ref>{{cite web |title=Métro2030 |url=http://www.ratp.fr/en/ratp/r_108501/metro2030-our-new-paris-metro/ |website=RATP (Paris metro operator) |access-date = 25 September 2016 |url-status=dead |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20161221051116/http://www.ratp.fr/en/ratp/r_108501/metro2030-our-new-paris-metro/ |archive-date = 21 December 2016 }}</ref> It is the second-busiest metro system in Europe after the ]. ] is the 24th-busiest railway station in the world and the busiest outside Japan, with 262{{nbsp}}million passengers in 2015.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://japantoday.com/category/features/travel/the-51-busiest-train-stations-in-the-world-all-but-6-located-in-japan |title=The 51 busiest train stations in the world – all but 6 located in Japan |work=Japan Today |date=6 February 2013 |access-date=22 April 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170422213423/https://japantoday.com/category/features/travel/the-51-busiest-train-stations-in-the-world-all-but-6-located-in-japan |archive-date=22 April 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref> Paris has one of the most ] systems<ref name=ICLEI/> and is one of only two cities in the world that received the ] twice.<ref name=Award/> | |||

| Centuries of cultural and political development have brought Paris a variety of museums, theatres, monuments and architectural styles. Many of its masterpieces such as the ] and the ] are iconic buildings, especially its internationally recognized symbol, the ]. Long regarded as an international centre for the arts, works by history's most famous painters can be found in the ], the ] and its many other museums and galleries. Paris is a global hub of fashion and has been referred to as the "international capital of style", noted for its ] tailoring, its high-end boutiques, and the twice-yearly ]. It is world renowned for its ], attracting many of the world's leading chefs. Many of France's most prestigious universities and '']'' are in Paris or its suburbs, and France's major newspapers '']'', '']'', '']'' are based in the city, and '']'' in ] near Paris. | |||

| Paris is known for its museums and architectural landmarks: the ] received 8.9{{nbsp}}million visitors in 2023, on track for keeping its position as the most-visited art museum in the world.<ref>"The Art Newspaper", 27 March 2023</ref> The ], ] and ] are noted for their collections of French ] art. The ], {{lang|fr|]|italic=no}}, ] and ] are noted for their collections of ] and ]. The historical district along the ] in the city centre has been classified as a ] since 1991.<ref name = "unesco">{{cite web |url=http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/600 |title=Paris, Banks of the Seine |website=UNESCO World Heritage Centre |publisher=United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization |access-date = 17 October 2021 |archive-date = 9 May 2019 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20190509014712/http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/600/ |url-status = live}}</ref> | |||

| Paris is home to the ] club ] and the ] club ]. The 80,000-seat ], built for the ], is located in Saint-Denis. Paris hosts the annual ] ] ] tournament on the red clay of ]. Paris played host to the ] and ], the ] and ], and the ]. The city is a major rail, highway, and air-transport hub, served by the two international airports ] and ]. Opened in 1900, the city's subway system, the ], serves 5.23 million passengers daily. Paris is the hub of the national road network, and is surrounded by three orbital roads: the ], the ] motorway, and the ] motorway in the outer suburbs. | |||

| Paris is home to several ] organizations including UNESCO, as well as other international organizations such as the ], the ], the ], the ], the ], along with European bodies such as the ], the ] and the ]. The football club ] and the ] club ] are based in Paris. The 81,000-seat ], built for the ], is located just north of Paris in the neighbouring commune of ]. Paris hosts the ], an annual ] tennis tournament, on the red clay of ]. Paris hosted the ], the ], and the ]. The ] and ] FIFA World Cups, the ], the ] and ] Rugby World Cups, as well as the ], ] and ] UEFA European Championships were held in Paris. Every July, the ] bicycle race finishes on the ]. | |||

| ==Toponyms== | |||

| :''See ] for the name of Paris in various languages other than English and French.'' | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| The name "Paris" is derived from that of some of its early inhabitants, the Celtic tribe known as the ]. The city was called ] (more fully, Lutetia Parisiorum, "Lutetia of the Parisii"), during the Roman era of the 1st to the 4th century AD, but during the reign of ] (360–3), the city was renamed Paris.{{sfn|Tellier|2009|p=231}} It is believed that the name of the Parisii tribe comes from the Celtic Gallic word ''parisio'', meaning "the working people" or "the craftsmen".{{sfn|Dottin|1920|p=277}} | |||

| {{hatnote|See ] for the name of Paris in various languages other than English and French.}} | |||

| The ancient ] that corresponds to the modern city of Paris was first mentioned in the mid-1st century BC by ] as ''Luteciam Parisiorum'' ('] of the ]') and is later attested as ''Parision'' in the 5th century AD, then as ''Paris'' in 1265.{{Sfn|Nègre|1990|p=155}}<ref name="Falileyev" /> During the Roman period, it was commonly known as {{Lang|la|Lutetia}} or {{Lang|la|Lutecia}} in Latin, and as ''Leukotekía'' in Greek, which is interpreted as either stemming from the ] root ''*lukot-'' ('mouse'), or from *''luto-'' ('marsh, swamp').{{Sfn|Lambert|1994|p=38}}{{Sfn|Delamarre|2003|p=211}}<ref name="Falileyev" /> | |||

| The name ''Paris'' is derived from its early inhabitants, the ], a ] tribe from the ] and the ].{{Sfn|Delamarre|2003|p=247}} The meaning of the Gaulish ] remains debated. According to ], it may derive from the Celtic root ''pario-'' ('cauldron').{{Sfn|Delamarre|2003|p=247}} ] interpreted the name as 'the makers' or 'the commanders', by comparing it to the ] ''peryff'' ('lord, commander'), both possibly descending from a ] form reconstructed as *''kwar-is-io''-.{{Sfn|Busse|2006|p=199}} Alternatively, ] proposed to translate ''Parisii'' as the 'spear people', by connecting the first element to the ] ''carr'' ('spear'), derived from an earlier *''kwar-sā''.<ref name="Falileyev">{{harvnb|Falileyev|2010}}, s.v. ''Parisii'' and ''Lutetia''.</ref> In any case, the city's name is not related to the ] of ]. | |||

| Paris has many nicknames, like "The City of Love", but its most famous is "''La Ville-Lumière''" ("The City of Light"),{{sfn|Robertson|2010|p=37}} a name it owes first to its fame as a centre of education and ideas during the ]. The sobriquet's "light" took on a more literal sense when Paris became one of the first European cities to adopt gas ]ing: the ] was Paris' first gas-lit throughfare from 1817.{{sfn|Maréchal|1894|p=8}} | |||

| Residents of the city are known in English as Parisians and in French as ''Parisiens'' ({{IPA|fr|paʁizjɛ̃||Parisien2.ogg}}). They are also pejoratively called ''Parigots'' ({{IPA|fr|paʁiɡo||Parigot.ogg}}).<ref group="note">The word was most likely created by Parisians of the lower popular class who spoke *argot*, then *parigot* was used in a provocative manner outside the Parisian region and throughout France to mean Parisians in general.</ref>{{sfn|Dottin|1920|p=535}} | |||

| Since the mid-19th century, Paris has been known as ''Paname'' ({{IPA|}}) in the Parisian ] called ] (]'']'', i.e. "I'm from Paname").{{sfn|Oscherwitz|2010|p=135}} The singer ] repopularised the term among the younger generation with his 1976 album '']'' ("In love with Paname").{{sfn|Leclanche|1998|p=55}} | |||

| Inhabitants are known in English as "Parisians" and in French as ''Parisiens'' ({{IPA-fr|paʁizjɛ̃||Parisien2.ogg}}) and ''Parisiennes''. Parisians were often pejoratively called ''Parigots'' ({{IPA-fr|paʁiɡo||Parigot.ogg}}) and ''Parigotes'', a term first used in 1900 by those living outside the Paris region<!-- word was more likely created by Parisians of the lower popular class who spoke *argot*, then * parigot* was used in a provacative manner outside the Parisian region & throughout France to mean Parisians in general/FW-->.{{sfn|Dottin|1920|p=535}} | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{Main|History of Paris}} | {{Main|History of Paris}} | ||

| {{For timeline}} | |||

| === |

===Origins=== | ||

| {{main|Lutetia}} | |||

| In 2006 French explorers digging near rue Henri-Farman in the 15th arrondissement, not far from the left bank of the Seine, discovered the oldest traces of human habitation in Paris, an encampment of hunter-gatherers dating to the ] period, between 9800 and 7500 BC.<ref>''Dictionnaire Historique de Paris'' (2013), Le Livre de Poche, p. 606</ref> Other traces of temporary settlements were found at ] in 1991, dating from around 4500–4200 BC.<ref name="roman_chronology">{{cite web|url=http://www.paris.culture.fr/en/ow_chrono.htm|title=Paris, Roman City –Chronology|publisher=Mairie de Paris|accessdate=16 July 2006}}</ref> The excavations at Bercy found the fragments of three wooden canoes used by fishermen on the Seine, the oldest dating to 4800-4300 BC. They are now on display at the ].{{sfn|Lawrence|Gondrand|2010|p=26}}<ref>{{fr icon}} . Ina.fr. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.</ref><ref>{{fr icon}} . Ina.fr. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.</ref> Excavations at the rue Henri-Farman site found traces of settlements from the middle ] period (4200-3500 BC); the early ] (3500-1500 BC); and the first ] (800-500 BC). The archaeologists found ceramics, animal bone fragments, and pieces of polished axes.<ref>''Dictionnaire Historique de Paris'' (2013), Le Livre de Poche, p. 608.</ref> Hatchets made in eastern Europe were found at the Neolithic site in Bercy, showing that first Parisians were already trading with settlements in other parts of the continent.<ref>Combeau, Yvan, ''Histoire de Paris'' (1999), Presses Universitaires de France, p.6.</ref> | |||

| The '']'', a sub-tribe of the ]ic ], inhabited the Paris area from around the middle of the 3rd century BC.{{sfn|Arbois de Jubainville|Dottin|1889|p=132}}{{sfn|Cunliffe|2004|p=201}} One of the area's major north–south trade routes crossed the ] on the ], which gradually became an important trading centre.{{sfn|Lawrence|Gondrand|2010|p=25}} The Parisii traded with many river towns (some as far away as the Iberian Peninsula) and minted their own coins.{{sfn|Schmidt|2009|pp=65–70}} | |||

| ], 1st century BC]] | |||

| The ] conquered the ] in 52 BC and began their settlement on Paris's ].{{sfn|Schmidt|2009|pp=88–104}} The Roman town was originally called ] (more fully, ''Lutetia Parisiorum'', "Lutetia of the Parisii", modern French ''Lutèce''). It became a prosperous city with a forum, baths, temples, theatres, and an ].{{sfn|Schmidt|2009|pp=154–167}} | |||

| ===The Parisii and the Roman conquest (250 BC – 52 BC)=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Between 250 and 225 BC, during the Iron Age, the '']'', a sub-tribe of the ]ic ], settled on the Ile de la Cité and on the banks of the Seine. At the beginning of the 2nd century BC they built an ], a walled fort, either on the Ile de la Cité or nearby (no trace of it has ever been found), and they built the first bridges over the Seine.<ref name="Combeau, Yvan 1999 p.6">Combeau, Yvan, ''Histoire de Paris'' (1999), Presses Universitaires de France, p.6.</ref> The settlement was called Lucotocia (according to the ancient Greek geographer ]) or Leucotecia (according to Roman geographer ]), and may have taken its name from the Celtic word ''lugo'' or ''luco'', for a marsh or swamp.<ref>Schmidt, ''Lutèce,- Paris, des origins à Clovis'' (2009), p. 28-29.</ref> It was the easiest place to cross the Seine, and it had a strategic position on the main trade route, via the Seine and the Rhone rivers, between Britain and to the Roman colony of Provence and the Mediterranean.{{sfn|Arbois de Jubainville|Dottin|1889|p=132}}{{sfn|Cunliffe|2004|p=201}} The location and the fees for crossing the bridge and passing along the river made the new town prosperous,{{sfn|Lawrence|Gondrand|2010|p=25}} so much so it was able to mint its own gold coins, which were used for trade across Europe. Coins from the towns along the Rhine and Danube and even from Cádiz in Spain were found in the excavations of the ancient city.<ref>Schmidt, ''Lutèce,- Paris, des origins à Clovis'' (2009), p. 69-70.</ref> | |||

| By the end of the ], the town was known as ''Parisius'', a ] name that would later become ''Paris'' in French.{{Sfn|Meunier|2014|p=12}} ] was introduced in the middle of the 3rd century AD by Saint ], the first Bishop of Paris: according to legend, when he refused to renounce his faith before the Roman occupiers, he was beheaded on the hill which became known as ''Mons Martyrum'' (Latin "Hill of Martyrs"), later "]", from where he walked headless to the north of the city; the place where he fell and was buried became an important religious shrine, the ], and many French kings are buried there.{{sfn|Schmidt|2009|pp=210–211}} | |||

| ] and his Roman army campaigned in Gaul between 58 and 53 BC, under the pretext of protecting the territory from Germanic invaders, but in reality to conquer it and annex it to the Roman Republic.<ref>Schmidt, ''Lutèce,- Paris, des origins à Clovis'' (2009), p. 74-76.</ref> In the summer of 53 BC he visited the city, and addressed the delegates of the Gallic tribes, assembled before the temple on the Ile de la Cite, asking for them to contribute soldiers and money to his campaign.<ref>Caesar, ''Commentary on the Gallic War'', Book 6, chapter 3.</ref> Wary of the Romans, the Lutecians listened politely to Caesar, offered to provide some cavalry, but formed a secret alliance with the other Gallic tribes, under the leadership of ], and launched an uprising against the Romans in January 52 BC.<ref>Schmidt, ''Lutèce,- Paris, des origins à Clovis'' (2009), p. 80-81.</ref> | |||

| ], the first king of the ], made the city his capital from 508.<ref>Patrick Boucheron, et al., eds. ''France in the World: A New Global History'' (2019) pp 81–86.</ref> As the Frankish domination of Gaul began, there was a gradual immigration by the ] to Paris and the Parisian ] dialects were born. Fortification of the ] failed to avert ], but Paris's strategic importance—with its bridges preventing ships from passing—was established by successful defence in the ], for which the then ] (''comte de Paris''), ], was elected king of ].{{sfn|Jones|1994|p=48}} From the ] dynasty that began with the 987 election of ], Count of Paris and ] (''duc des Francs''), as king of a unified West Francia, Paris gradually became the largest and most prosperous city in France.{{sfn|Schmidt|2009|pp=210–211}} | |||

| Caesar responded quickly. He force-marched six legions north to Orleans, where the rebellion had begun, and then to Gergovia, the home of Vercingetorix. At the same time he sent his deputy, ], with four legions, to subdue the Parisii and their allies, the Senons. The Commander of the Parisii, ], burned the bridge that connected the oppidum to the left bank of the Seine, so the Romans were unable to approach the town. The Labienus and the Romans went downstream, built their own pontoon bridge at ], and approached Lutetia on the right bank. Camulogene responded by burning the bridge to the right bank, and burning the town on the Ile-de-la-Cite, before retreating to the left bank, and making camp at what is now ]. Labienus deceived the Parisii with a clever ruse; in the middle of the night, he sent part of his army, making as much noise as possible, upstream to Melun, left his most inexperienced soldiers in their camp on the right bank, and, with his best soldiers, quietly crossed the Seine to the left bank and laid a trap for the Parisii. Camulogene, believing that the Romans were retreating, divided his own forces, some to capture the Roman camp, which he thought was abandoned, and others to pursue the Roman army. Instead, he ran directly into the best two Roman legions on the plain of Grenelle, near the site of the Eiffel Tower and the ]. The Parisii fought bravely and desperately in what became known as the ]; Camulogene was killed and his soldiers were cut down by the disciplined Romans. Despite the defeat, the Parisii continued to resist the Romans; they sent eight thousand men to fight with Vercingetorix in his last stand against the Romans at the ].<ref>Schmidt, ''Lutèce,- Paris, des origins à Clovis'' (2009), p. 88-104</ref> | |||

| === |

===High and Late Middle Ages to Louis XIV=== | ||

| {{See also|Paris in the Middle Ages|Paris in the 16th century|Paris in the 17th century}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] and ], viewed from the Left Bank, from the ] (month of June) (1410)]] | |||

| ], (14-37 AD), a monument to both Roman and Gallic gods, dedicated by the guild of boatmen of Paris. The original pieces are now in the ]]] | |||

| The Romans built an entirely new city as a base for their soldiers and the Gallic auxiliaries, intended to keep an eye on the rebellious province. The new city was called Lutetia or Lutetia Parisiorum (Lutece of the Parisii). The name probably came from the Latin word ''luta'', meaning mud or swamp <ref name="Paris 2013 p. 412">''Dictionnaire Historique de Paris'' (2013), p. 412.</ref> Caesar had described the great marsh, or ''marais'', along the right bank of the Seine.<ref>Combeau, Yves, ''Histoire de Paris'' (2013), p. 8-9.</ref> The major part of the city was on the left bank of the Seine, which was higher and less prone to flood. It was laid out following the traditional Roman town design, along a north-south axis (known in Latin as the ''card maximus''). On the left bank, the main Roman street followed the route of the modern day rue Saint-Jacques. It crossed the Seine and traversed the Ile de la cite on two wooden bridges; the Petit Pont and the Grand Pont (today's Pont Notre-Dame). The port of the city, where the boats docked, was located on the island, where the parvis of Notre Dame is today. On the right bank, it followed the modern rue Saint-Martin. .<ref name="Paris 2013 p. 412"/> On the left bank, the ''cardo'' was crossed by a less-important east-west ''decumanus'', now the modern rues Cujas, Soufflot and des Ecoles. | |||

| By the end of the 12th century, Paris had become the political, economic, religious, and cultural capital of France.{{sfn|Lawrence|Gondrand|2010|p=27}} The ], the royal residence, was located at the western end of the Île de la Cité. In 1163, during the reign of ], ], bishop of Paris, undertook the construction of the ] at its eastern extremity. | |||

| The city was centred on the forum, atop ], between Boulevard Saint-Michel and rue Saint-Jacques, where rue Soufflot is now located. The main building of the forum was one hundred metres long, and contained a temple, a basilica used for civic functions, and a square portico which covered shops. Nearby, on the slope of the hill, was an enormous amphitheater, built in the 1st century AD, which could seat ten to fifteen thousand spectators, though the population of the city was only six to eight thousand.<ref>Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris: Politique, urbanisme, civilisation (2012). p. 12</ref> Fresh drinking water was supplied to the city by an aqueduct sixteen kilometres long from the basin of Rungis and Wissous. The aqueduct also supplied water to the famous baths, or ], built at the end of the 2nd century or beginning of the 3rd century AD, near the forum. | |||

| After the marshland between the river Seine and its slower 'dead arm' to its north was filled in from around the 10th century,{{sfn|Bussmann|1985|p=22}} Paris's cultural centre began to move to the Right Bank. In 1137, a new city marketplace (today's ]) replaced the two smaller ones on the ] and ].{{sfn|de Vitriaco|Hinnebusch|1972|p=262}} The latter location housed the headquarters of Paris's river trade corporation, an organisation that later became, unofficially (although formally in later years), Paris's first municipal government. | |||

| The most important monument left from the Roman city is the ], a stone column, with figures of both Roman and Celtic gods, built by the guild of boatmen between 14-37 AD, during the reign of the Emperor ]. It was discovered in 1711 under the choir of the cathedral of Notre Dame, and the pieces are now in the ].<ref>Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris: Politique, urbanisme, civilisation'' (2012). p. 12</ref> | |||

| In the late 12th century, ] extended the ] fortress to defend the city against river invasions from the west, gave the city its first walls between 1190 and 1215, rebuilt its bridges to either side of its central island, and paved its main thoroughfares.{{sfn|Sarmant|2012|pp=36–40}} In 1190, he transformed Paris's former cathedral school into a student-teacher corporation that would become the ] and would draw students from all of Europe.{{sfn|Sarmant|2012|pp=28–29}}{{sfn|Lawrence|Gondrand|2010|p=27}} | |||

| Besides the Roman architecture and city design, the newcomers imported Roman cuisine; modern excavations have found amphorae of Italian wine and olive oil, shellfish, and a popular Roman sauced called garum.<ref name="Paris 2013 p. 412"/> Despite its commercial importance, Lutetia was only a medium-sized Roman city, considerably smaller than ] or ], which was the capital of the Roman province of Quatrieme Lyonnaise, where Lutetia was located.<ref name="Combeau, Yvan 2013 p. 11">Combeau, Yvan, ''Histoire de Paris'' (2013), p. 11</ref> | |||

| With 200,000 inhabitants in 1328, Paris, then already the capital of France, was the most populous city of Europe. By comparison, London in 1300 had 80,000 inhabitants.<ref name=ParisDigest>{{Cite web |url=https://www.parisdigest.com/history/paris_history.htm |title=Paris history facts |date=2018 |publisher=Paris Digest |access-date=6 September 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180906195637/https://www.parisdigest.com/history/paris_history.htm |archive-date=6 September 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref> By the early fourteenth century, so much filth had collected inside urban Europe that French and Italian cities were naming streets after human waste. In medieval Paris, several street names were inspired by {{Lang|fr|merde}}, the French word for "shit".<ref>John Kelly, ''"The Great Mortality"'' (2005). pp 42</ref> | |||

| ] was introduced into Paris in the middle of the 3rd century AD. According to tradition, it was brought by Saint ], the Bishop of the Parisii, who, along with two others, Rustique and Eleuthere, was arrested by the Roman prefect Fescennius. When he refused to renounce his faith, he was beheaded on Mount Mercury. According to the tradition, Saint Denis picked up his head and carried it to a secret Christian cemetery of Vicus Cattulliacus, about six miles away. A different version of the legend says that a devout Christian woman, Catula, came at night to the site of the execution and took his remains to the cemetery. The hill where he was executed, Mount Mercury, later became the Mountain of Martrys (Mons Martyrum), eventually ].<ref>Schmidt, Joel, ''Lutece: Paris, des origines a Clovis (2009). pp. 210-211.</ref> A church was built on the site of the grave of St. Denis, which later became the ]. By the 4th century, the city had its first recognized Bishop, Victorinus. (346 AD). By 392 AD it had a cathedral.<ref name="Sarmant, Thierry 2012 p. 16-18">Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris: Politique, urbanisme, civilization'' (2012), p. 16-18.</ref> | |||

| ] ({{Circa}} 15th–16th), former residence of the Archbishop of Sens]] | |||

| During the ], Paris was occupied by England-friendly ] from 1418, before being occupied outright by the English when ] entered the French capital in 1420;<ref>Du Fresne de Beaucourt, G., ''Histoire de Charles VII'', Tome I: ''Le Dauphin'' (1403–1422), Librairie de la Société bibliographiqque, 35 Rue de Grenelle, Paris, 1881, pp. 32 & 48</ref> in spite of a 1429 effort by ] to liberate the city,{{sfn|Fierro|1996|pages=52–53}} it would remain under English occupation until 1436. | |||

| In the late 16th-century ], Paris was a stronghold of the ], the organisers of 24 August 1572 ] in which thousands of French Protestants were killed.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/516821/Massacre-of-Saint-Bartholomews-Day |title=Massacre of Saint Bartholomew's Day |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online |access-date=23 November 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150504150458/https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/516821/Massacre-of-Saint-Bartholomews-Day |archive-date=4 May 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref>{{sfn|Bayrou|1994|pp=121–130}} The conflicts ended when pretender to the throne ], after converting to Catholicism to gain entry to the capital, entered the city in 1594 to claim the crown of France. This king made several improvements to the capital during his reign: he completed the construction of Paris's first uncovered, sidewalk-lined bridge, the ], built a Louvre extension connecting it to the ], and created the first Paris residential square, the Place Royale, now ]. In spite of Henry IV's efforts to improve city circulation, the narrowness of Paris's streets was a contributing factor in his assassination near ] marketplace in 1610.{{sfn|Fierro|1996|p=577}} | |||

| Late in the 3rd century AD, the invasion of Germanic tribes, beginning with the ] in 275 AD, caused many of the residents of the left bank to leave that part of the city and move to the safety of the Ile de la Cité. Many of the monuments on the left bank were abandoned, and the stones used to build a wall around the Ile de la Cite, the first city wall of Paris. A new basilica and baths were built on the island; their ruins were found beneath the square in front of the Cathedral of Notre Dame.<ref>Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris: Politique, urbanisme, civilisation'' (2012). p. 14</ref> About the same time, the name Lutetia was gradually replaced by Civitas Parisiorum, or "City of the Parisii,." and then simply Paris.<ref name="Combeau, Yvan 2013 p. 11"/> In February 360 the city became the de-facto capital of the Western Roman Empire when ], the nephew of ] and Prefect of Gaul, was proclaimed Emperor by his soldiers.{{sfn|d'Istria|2002|p=6}} When he was not campaigning with his army, he spent the winters of 357-358 and 359-360 in the city, living in a palace on the site of the modern ] writing and establishing his reputation as a philosopher.<ref>Combeau, Yvan, ''Histoire de Paris'' (2013), p. 12</ref> Two other Emperors spent winters in the city near the end of the Roman Empire, trying to halt the tide of barbarian invasions; ] (365-367) and ] in 383 AD.<ref name="Sarmant, Thierry 2012 p. 16-18"/> | |||

| During the 17th century, ], chief minister of ], was determined to make Paris the most beautiful city in Europe. He built five new bridges, a new chapel for the ], and a palace for himself, the ]. After Richelieu's death in 1642, it was renamed the ].{{sfn|Fierro|1996|p=582}} | |||

| The gradual collapse of the Roman empire due to the increasing ] of the 5th century, sent the city into a period of decline. In 451 AD the city was threatened by the army of ], which had pillaged ], ] and ] The Parisians were planning to abandon the city, but they were persuaded to resist by ] (422-502). Attila bypassed Paris and attacked ]. In 461 the city was threatened again by the ] Franks, led by ]. (436-481). The siege of the city lasted ten years. Once again Genevieve organised the defence. She rescued the city by bringing wheat to the hungry city from Brie and Champagne on a flotilla of eleven barges. She became the patron saint of Paris.<ref>Combeau, Yvan, ''Histoire de Paris'' (2013), pp. 13-14.</ref> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In 481, the son of Childeric, ], just sixteen years old, became the new ruler of the Franks. In 486, he defeated the last Roman armies, and became the ruler of all of Gaul north of the ]. With the consent of Genevieve, he entered Paris. He was converted to Christianity by his wife Clothilde, was baptised at Reims in 496, and made Paris his capital.<ref>Combeau, Yvan, ''Histoire de Paris'', (2013), pp. 13-14.</ref> | |||

| Due to the Parisian uprisings during the ] civil war, ] moved his court to a new palace, ], in 1682. Although no longer the capital of France, arts and sciences in the city flourished with the ], the Academy of Painting, and the ]. To demonstrate that the city was safe from attack, the king had the ] demolished and replaced with tree-lined boulevards that would become the '']''.{{Sfn|Combeau|2003|pp=42–43}} Other marks of his reign were the ], the ], the ], and ].{{sfn|Fierro|1996|pp=590–591}} | |||

| === |

===18th and 19th centuries=== | ||

| {{See also|Paris in the 18th century|Paris during the Second Empire|Haussmann's renovation of Paris}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Paris grew in population from about 400,000 in 1640 to 650,000 in 1780.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yKsYAAAAYAAJ |last1=Durant |first1=Will |last2=Durant |first2=Ariel |title=The Story of Civilization XI The Age of Napoleon |date=1975 |publisher=Simon & Schuster |page=3 |access-date=11 February 2016 |isbn=978-0-671-21988-8 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161229054200/https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Story_of_Civilization_The_age_of_Nap.html?id=yKsYAAAAYAAJ |archive-date=29 December 2016 |url-status=live}}</ref> A new boulevard named the ] extended the city west to ],{{Sfn|Combeau|2003|pp=45–47}} while the working-class neighbourhood of the ] on the eastern side of the city grew increasingly crowded with poor migrant workers from other regions of France.{{sfn|Sarmant|2012|pp=129–133}} | |||

| ], the first Christian king to rule over Paris, made the Paris his capital from 508. He and his successors of the ] built a host of churches; a basilica on Montagne Saint-Genevieve, near where the Roman forum had been; the Cathedral of Saint-Étienne where Notre Dame is now; and several important monasteries, including one in the fields of the left bank which later became the ]. They also built the Basilica of Saint-Denis, which became the traditional burial place of the Kings of France. None of the Merovingian buildings survived, but there are four marble Merovingian columns in the church of Saint-Pierre de Montmartre.<ref>Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris: Politique, urbanisme, civilisation'' (2012), p. 21-22.</ref> The kings of the ], who came to power in 751, moved the Frankish capital to ], and they paid little attention to Paris, though King ] did build an impressive new sanctuary at Saint-Denis, which was consecrated in the presence of ] himself on 24 February 775.<ref>Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris: Politique, urbanisme, civilisation'' (2012), p. 22</ref> | |||

| ] on 14 July 1789, by ]]] | |||

| ], a major landmark on the ], was completed in 1790.]] | |||

| In the 9th century, the city was repeatedly attacked by the VIkings, who sailed up the Seine on great fleets of ships. They demanded a ransom and ravaged the fields, and in 885-886 they laid siege to Paris for a year, and tried again in 887 and 889, but they were unable to conquer Paris itself, protected by the Seine and the walls on the Ile de a Cite. {{sfn|Lawrence|Gondrand|2010|p=27}}The two bridges, vital to the city, were additionally protected by two massive stone fortresses, the ] on the right bank, and the Petit Chatelet on the left bank, which were built on the initiative of Gauzlin, the bishop of Paris. The Grand Chatelet gave its name to the modern ], on the same site.<ref>Sarmant, ''History of Paris'', p. 24.</ref> {{sfn|Lawrence|Gondrand|2010|p=27}} | |||

| Paris was the centre of an explosion of philosophic and scientific activity, known as the ]. ] and ] published their '']'' in 1751, before the ] launched the first manned flight in a ] on 21 November 1783. Paris was the financial capital of continental Europe, as well the primary European centre for book publishing, fashion and the manufacture of fine furniture and luxury goods.{{sfn|Sarmant|2012|p=120}} On 22 October 1797, Paris was also the site of the first parachute jump in history, by ]. | |||

| In the summer of 1789, Paris became the centre stage of the ]. On 14 July, a mob seized the arsenal at the ], acquiring thousands of guns, with which it ], a principal symbol of royal authority. The first independent ], or city council, met in the ''Hôtel de Ville'' and elected a ], the astronomer ], on 15 July.{{sfn|Paine|1998|p=453}} | |||

| At the end of the 10th century, a new dynasty of kings, the Capetians, begun by ] in 987, came to power. Though they spent little time in the city, they restored the royal palace on the Ile de la Cite, and built a church where Saint-Chapelle stands today, Prosperity returned gradually to the city, and the right bank began to be populated. On the left bank, the nave, transept and first four sections of the tower of the church of Saint-Germain-des-Pres were built in the second part of the 11th century. The monastery next to it became famous for its illuminated manuscripts. | |||

| ] and the royal family were ] and incarcerated in the Tuileries Palace. In 1793, as the revolution turned increasingly radical, the king, queen and mayor were beheaded by ] in the ], along with more than 16,000 others throughout France.{{sfn|Fierro|1996|p=674}} The property of the aristocracy and the church was ], and the city's churches were closed, sold or demolished.{{sfn|Sarmant|2012|p=144}} A succession of revolutionary factions ruled Paris until ] (''coup d'état du 18 brumaire''), when ] seized power as First Consul.{{sfn|Sarmant|2012|p=147}} | |||

| ===Medieval Paris (12th-15th century)=== | |||

| ] as it appeared in the mid-15th century.]] | |||

| ] on the Île de la Cité is a masterpiece of the Gothic style. (12th century)]] | |||

| ] (1485–1510) on the left bank was the home of the Abbot of the Cluny Monastery, and is now the Museum of the Middie Ages.]] | |||

| In the 12th century, under the ] kings, Paris became the political, economic, religious and cultural capital of France. {{sfn|Lawrence|Gondrand|2010|p=27}} Between 1170 and 1220 the population of the city doubled, from 25,000 to 50,000, and the city expanded outwards on the right bank, to the Greve, Saint-Martin-des-Champs and the Temple, and on the left bank, around the abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Pres and the hill of Saint-Genevieve.<ref>Sarmant, ''History of Paris'', p. 28-29.</ref> {{sfn|Lawrence|Gondrand|2010|p=27}} | |||

| The population of Paris had dropped by 100,000 during the Revolution, but after 1799 it surged with 160,000 new residents, reaching 660,000 by 1815.{{sfn|Sarmant|2012|p=148}} Napoleon replaced the elected government of Paris with a prefect that reported directly to him. He began erecting monuments to military glory, including the ], and improved the neglected infrastructure of the city with new fountains, the ], ] and the city's first metal bridge, the ].{{sfn|Sarmant|2012|p=148}} | |||

| Under Louis VI and Louis VII, Paris became one of the principle centres of learning in Europe. Students, scholars and monks flocked to the city from England, Germany and Italy to engage in intellectual exchanges, to teach and be taught. They studied first in the different schools attached to Notre-Dame, and the Abbeys of Saint-Germain-des-Pres. The most famous teacher was ] (1079–1142), who taught five thousand students at at the Montagne Saint-Genevieve. The ] was originally formed as a corporation of students and teachers. It was recognised by King ] in 1200, and officially recognised by Pope Innocent III in 1215. Some twenty thousand students lived on the Left Bank, which became known as the Latin Quarter, because Latin was the language of instruction at the university. The poorer students lived in colleges (''Collegia pauperum magistrorum''), which were hotels where they were lodged and fed. In 1257 the Chaplain of Louis IX, ], opened the oldest and most famous College of the University, which later took his name, the ].<ref>Combeau, Yvan, ''Histoire de Paris'', p. 25-26</ref> From the 13th to the 15th century, the University of Paris was the most important school of catholic theology in Western Europe, whose teachers included ] from England, Saint ] from Italy, and Saint ] from Germany. {{sfn|Lawrence|Gondrand|2010|p=27}} <ref name="Sarmant, Thierry 2012 p. 29">Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris'' (2012) p. 29.</ref> | |||

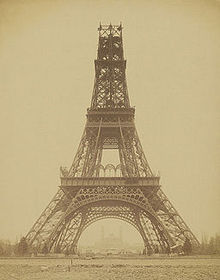

| ], under construction in November 1888, startled Parisians—and the world—with its modernity.]] | |||

| The flourishing of religious architecture in Paris was largely the work of ], the Abbé of Saint-Denis from 1122-1151, and advisor to King ] and ]. He rebuilt the façade of the old Carolingian ], dividing it into three horizontal levels and three vertical sections, symbolising the Holy Trinity. Then, from 1140 to 1144 AD, he rebuilt the rear of the church with a majestic and dramatic wall of stained glass windows, flooding the church with light. This style, which later was named ], was copied by other Paris churches: the ], ], and ], and quickly spread to England and Germany.<ref name="Sarmant, Thierry 2012 p. 29"/> | |||

| During the ], the bridges and squares of Paris were returned to their pre-Revolution names; the ] in 1830 (commemorated by the ] on the ]) brought to power a constitutional monarch, ]. The first railway line to Paris opened in 1837, beginning a new period of massive migration from the ] to the city.{{sfn|Sarmant|2012|p=148}} In 1848, Louis-Philippe was overthrown by a ] in the streets of Paris. His successor, ], alongside the newly appointed prefect of the Seine, ], launched a huge public works project to build wide new boulevards, a new opera house, a central market, new aqueducts, sewers and parks, including the ] and ].{{sfn|De Moncan|2012|pp=7–35}} In 1860, Napoleon III annexed the surrounding towns and created eight new arrondissements, expanding Paris to its current limits.{{sfn|De Moncan|2012|pp=7–35}} | |||

| During the ] (1870–1871), Paris was besieged by the ]. Following several months of blockade, hunger, and then bombardment by the Prussians, the city was forced to surrender on 28 January 1871. After seizing power in Paris on 28 March, a revolutionary government known as the ] held power for two months, before being harshly suppressed by the French army during the "]" at the end of May 1871.{{sfn|Rougerie|2014|p=118}} | |||

| An even more ambitious building project, a new cathedral for Paris, was begun by Bishop ] in about 1160, and continued for two centuries. The first stone of the choir of the Cathedral of ] was laid in 1163, and the altar consecrated in 1182. The façade was built between 1200 and 1225, and the two towers were built between 1225 and 1250. It was an immense structure, 125 meters long, with towers 63 meters high, and seats for 1300 worshippers. The plan of the cathedral was copied on a smaller scale on the left bank of the Seine, in the church of ],i<ref>Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris'' (2012) p. 33.</ref> | |||

| In the late 19th century, Paris hosted two major international expositions: the ], which featured the new Eiffel Tower, was held to mark the centennial of the French Revolution; and the ] gave Paris the ], the ], the {{Lang|fr|]|italic=no}} and the first ] line.{{sfn|Fraser|Spalding|2011|p=117}} Paris became the laboratory of ] (]) and ] (] and ]), and of ] in art (], ], ], ]).{{sfn|Fierro|1996|pp=490–491}} | |||

| The other great builder of Paris at the end of the 12th century was King ]. Between 1190 and 1202, he built the massive chateau du Louvre, designed to protect the right bank of the Seine against an English attack from Normandy. The fortress was a great rectangle 72 by 78 meters, surrounded by four towers a moat. In the center was a circular tower thirty meters high. The foundations can be seen today in the basement of Louvre Museum. Before he departed for the crusades, he began construction of new fortifications for the city. He built a stone wall on the left bank, with thirty round towers, On the right bank, the wall extended for 2.8 kilometres, with forty towers, protecting the new neighbourhoods of the growing medieval city. Many pieces of the wall can still be seen today, particularly in the Marais. His third great project, much appreciated by the Parisians, was to pave the foul-smelling mud streets of the city with stone. He also rebuilt the city's two wooden bridges, the Petit-Pont and Grand-Pont, in stone, and he began construction on the right bank of a covered market, which took the name ].<ref name="Sarmant, Thierry 2012 p. 36-40">Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris'' (2012) p. 36-40.</ref> | |||

| ===20th and 21st centuries=== | |||

| In the 13th century, ], (1226–1270), known to history as Saint Louis, built the masterpiece of Gothic Art, ] specially to house relics from the Cruxifixion of Christ. Built between 1241 and 1248, it has the oldest stained glass windows existing in Paris. At the same time that Saint-Chapelle was built, the great stained glass rose windows, eighteen meters high, were added to the transept of Notre Dame Cathedral.<ref name="Sarmant, Thierry 2012 p. 36-40"/> | |||

| {{See also|Paris in the Belle Époque|Paris during the First World War|Paris between the Wars (1919–1939)|Paris in World War II|History of Paris (1946–2000)}} | |||

| By 1901, the population of Paris had grown to about 2,715,000.{{sfn|Combeau|2003|p=61}} At the beginning of the century, artists from around the world including ], ], and ] made Paris their home. It was the birthplace of ], ] and ],{{sfn|Fierro|1996|p=497}}<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3hYBzRzZ0kcC |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151118065327/https://books.google.com/books/about/Bohemian_Paris.html?id=3hYBzRzZ0kcC |url-status=dead |title=Bohemian Paris: Picasso, Modigliani, Matisse, and the Birth of Modern Art |first=Dan |last=Franck |date=1 December 2007 |archive-date=18 November 2015 |publisher=Open Road + Grove/Atlantic |via=Google Books |isbn=978-0-8021-9740-5}}</ref> and authors such as ] were exploring new approaches to literature.{{sfn|Fierro|1996|p=491}} | |||

| During the ], Paris sometimes found itself on the front line; 600 to 1,000 Paris taxis played a small but highly important symbolic role in transporting 6,000 soldiers to the front line at the ]. The city was also bombed by ]s and shelled by German ].{{sfn|Fierro|1996|p=750}} In the years after the war, known as '']'', Paris continued to be a mecca for writers, musicians and artists from around the world, including ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]<ref>William A. Shack, ''Harlem in Montmartre, A Paris Jazz Story between the Great Wars'', University of California Press, 2001. {{ISBN|978-0-520-22537-4}},</ref> and ].<ref name=Meisler>{{cite web |last1=Meisler |first1=Stanley |title=The Surreal World of Salvador Dalí |url=http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-surreal-world-of-salvador-dali-78993324/ |website=Smithsonian.com |publisher=Smithsonian Magazine |access-date=12 July 2014 |date=April 2005 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140518170614/http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-surreal-world-of-salvador-dali-78993324/ |archive-date=18 May 2014 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Beginning in the 11th century, Paris had been governed by a Royal Prevot, appointed by the King, who lived in the Grand Chatelet fortress. Saint Louis created a new position, the Prevot of the Merchants, to share authority with the Royal Prevot, recognise the growing power and wealth of the merchants of Paris. He also created the first municipal council of Paris with twenty-four members. The guilds of craftsmen also were growing in importance; the city took its coat of arms, featuring a ship, from the symbol of the guild of the boatmen. In 1328 The city population was about two hundred thousand, making it the largest city in Europe, more populous than London or Rome. With the growth in population came growing social tensions; the first riots took place in December 1306 against the Prevot of the merchants, accused of raising rents. Houses of many merchants were burned, and twenty-eight rioters were hanged.<ref name="Sarmant, Thierry 2012 p. 44-45">Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris'' (2012) p. 44-45</ref> | |||

| In the years after the ], the city was also home to growing numbers of students and activists from ] and other Asian and African countries, who later became leaders of their countries, such as ], ] and ].<ref>Goebel, {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150904011013/http://www.cambridge.org/us/academic/subjects/history/twentieth-century-european-history/anti-imperial-metropolis-interwar-paris-and-seeds-third-world-nationalism?format=HB#contentsTabAnchor |date=4 September 2015 }}.</ref> | |||

| King ] (I1285-1314) continued the building tradition of Saint-Louis. He reconstructed the royal residence on the Île de la Cité. transforming it from a fortress into a palace. Two of the great ceremonial halls still remain, within the structure of the Palais de Justice. He also built a more sinister structure, the gibet of Montfacuon, where the bodies of executed criminals were displayed, near the modern Place Fabien and the ]. On 13 October 1307, he used his royal power to arrest the members of the ], whom he felt had grown too powerful, and on 18 March 1314, he had the Grand Master of the Order, ], burned alive on the point of the Île de la Cité.<ref>Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris'' pp. 43-44.</ref> | |||

| ] on the Champs-Élysées celebrating the liberation of Paris, 26 August 1944]] | |||

| In the middle of the 14h century, Paris was struck by two great catastrophes; the ] and the ]. In the first epidemic of the plague in 1348-1349, forty to fifty thousand Parisians died, a quarter of the population. The plague returned in 1360-61, in 1363, and 1366-1368. {{sfn|Byrne|2012|p=259}} <ref name="Sarmant, Thierry 2012 p. 46">Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris'' (2012) p. 46</ref> During the 16th and 17th centuries, ] visited the city almost one year out of three.{{sfn|Harding|2002|p=25}} | |||

| On 14 June 1940, the German army marched into Paris, which had been declared an "]".{{sfn|Sarmant|2012|p=217}} On 16–17 July 1942, following German orders, the French police and gendarmes arrested 12,884 Jews, including 4,115 children, and confined them during five days at the ] (''Vélodrome d'Hiver''), from which they were transported by train to the extermination camp at ]. None of the children came back.{{sfn|Fierro|1996|p=637}}{{sfn|Sarmant|2012|p=218}} On 25 August 1944, the city was liberated by the ] and the ] of the ]. General ] led a huge and emotional crowd down the Champs Élysées towards Notre Dame de Paris and made a rousing speech from the ].{{sfn|Fierro|1996|pp=242–243}} | |||

| In the 1950s and the 1960s, Paris became one front of the ] for independence; in August 1961, the pro-independence ] targeted and killed 11 Paris policemen, leading to the imposition of a curfew on Muslims of Algeria (who, at that time, were French citizens). On 17 October 1961, an unauthorised but peaceful protest demonstration of Algerians against the curfew led to ] between the police and demonstrators, in which at least 40 people were killed. The anti-independence ] (OAS) carried out a series of bombings in Paris throughout 1961 and 1962.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/oct/17/france-remembers-algerian-massacre |title=France remembers Algerian massacre 50 years on |author=Kim Willsher |newspaper=The Guardian |access-date=26 October 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141026114936/http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/oct/17/france-remembers-algerian-massacre |archive-date=26 October 2014 |url-status=live |date=17 October 2011}}</ref>{{sfn|Fierro|1996|p=658}} | |||

| The war was even more catastrophic. Beginning in 1346, the English army of King ] pillaged the countryside outside the walls of Paris. Ten years later, when King ] was captured by the English at the ], disbanded French soldiers looted and ravaged the surroundings of Paris. In 1358, the Prevot of the Merchants of Paris, ], led a rebellion against the royal government. He was killed by royal soldiers who feared he would surrender the city to the English. Gvhca The new King, ], built a new wall of fortifications around the city, including a large fortress guarding the gate of Saint-Antoine, at the east end of the city; it became known as the ]. He moved his residence from the Ile de la Cite to the Louvre and built an imposing new castle at Vincennes, east of city.<ref name="Sarmant, Thierry 2012 p. 46"/> | |||

| In May 1968, protesting students occupied the ] and put up barricades in the ]. Thousands of Parisian blue-collar workers joined the students, and the movement grew into a two-week general strike. Supporters of the government won the June elections by a large majority. The ] resulted in the break-up of the University of Paris into 13 independent campuses.{{sfn|Sarmant|2012|p=226}} In 1975, the National Assembly changed the status of Paris to that of other French cities and, on 25 March 1977, ] became the first elected mayor of Paris since 1793.{{sfn|Fierro|1996|p=260}} The ], the tallest building in the city at 57 storeys and {{cvt|210|m|ft|0|abbr=off}} high, was built between 1969 and 1973. It was highly controversial, and it remains the only building in the centre of the city over 32 storeys high.{{sfn|Sarmant|2012|p=222}} The population of Paris dropped from 2,850,000 in 1954 to 2,152,000 in 1990, as middle-class families moved to the suburbs.{{sfn|Combeau|2003|pp=107–108}} A suburban railway network, the ] (Réseau Express Régional), was built to complement the Métro; the ] expressway encircling the city, was completed in 1973.{{sfn|Bell|de-Shalit|2011|p=247}} | |||

| More misfortunes followed for Paris. An English army and its allies from the ] occupied Paris on December 1, 1420. Beginning in 1422, the north of France was ruled by the ], the Regent for the young King ], resident in Paris, while the King of France ruled only France south of the Loire River. When ] tried to liberate Paris on 8 September 1429, the Parisian merchant class joined with the English and Burgundians in keeping her out.<ref name="Sarmant, Thierry 2012 p. 46"/> King Henry VI of England was crowned King of France at Notre Dame Cathedral on 16 December 1431. The English did not leave Paris until 1436, when ], was finally able to return. Many neighbourhoods were in ruins; a hundred thousand people, half the population, had left. | |||

| Most of the postwar presidents of the ] wanted to leave their own monuments in Paris; President ] started the ] (1977), ] began the ] (1986); President ] had the ] built (1985–1989), the new site of the '']'' (1996), the ] (1985–1989) in ], as well as the ] with its underground courtyard (1983–1989); ] (2006), the ].{{sfn|Sarmant|2012|pp=226–230}} | |||

| Paris became France's capital once again, the succeeding monarchs chose to live in the ], returning to Paris only on special occasions.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://articles.cnn.com/2008-03-07/travel/loire.valley_1_chenonceau-chateaux-loire-valley?_s=PM:TRAVEL|title=Loire Valley: Land of a thousand chateaux|last1=Steves|first1=Rick|date=7 March 2007|publisher=CNN|accessdate=4 January 2013}}{{dead link|date=July 2013}}</ref> ] finally returned the royal residence to Paris in 1528. | |||

| In the early 21st century, the population of Paris began to increase slowly again, as more young people moved into the city. It reached 2.25 million in 2011. In March 2001, ] became the first socialist mayor. He was re-elected in March 2008.<ref>{{cite web |title=City Mayors: Bertrand Delanoe – Mayor of Paris |url=http://www.citymayors.com/mayors/paris_mayor.html |website=www.citymayors.com |access-date=16 August 2023 |archive-date=22 July 2012 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20120722044933/http://www.citymayors.com/mayors/paris_mayor.html |url-status=live }}</ref> In 2007, in an effort to reduce car traffic, he introduced the ], a system which rents bicycles. Bertrand Delanoë also transformed a section of the highway along the Left Bank of the Seine into an urban promenade and park, the ], which he inaugurated in June 2013.<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.lemoniteur.fr/133-amenagement/article/actualite/21534070-les-berges-de-seine-rendues-aux-parisiens |title=Les berges de Seine rendues aux Parisiens |journal=Le Moniteur |date=19 June 2013 |access-date=2 December 2014 |language=fr |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141220195103/http://www.lemoniteur.fr/133-amenagement/article/actualite/21534070-les-berges-de-seine-rendues-aux-parisiens |archive-date=20 December 2014 |url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| Two large residences from the Middle Ages can still be seen in Paris; the ], the residence of the Archbishop of Sens (end of the 15th century), now the Forney Library; and the ] (1485–1510), the former residence of the Abbot of the Cluny Monastery, now the Museum of the Middle Ages. The oldest surviving house in Paris is the house of ], (1407), located at 51 rue de Montmorency. It was not a private home, but a hostel for the poor.<ref name="Sarmant, Thierry 2012 p. 44-45"/> | |||

| ], Paris, 11 January 2015, during the ] after the ]]] | |||

| In 2007, President ] launched the ] project, to integrate Paris more closely with the towns in the region around it. After many modifications, the new area, named the ], with a population of 6.7 million, was created on 1 January 2016.<ref name="Lichfield">{{cite news |title=Sarko's €35bn rail plan for a 'Greater Paris' |url=https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/sarkos-euro35bn-rail-plan-for-a-greater-paris-1676196.html |date=29 April 2009 |newspaper=] |access-date=12 June 2009 |location=London |first=John |last=Lichfield |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090502102151/http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/sarkos-euro35bn-rail-plan-for-a-greater-paris-1676196.html |archive-date=2 May 2009 |url-status=live}}</ref> In 2011, the City of Paris and the national government approved the plans for the ], totalling {{cvt|205|km|mi|abbr=off}} of automated metro lines to connect Paris, the innermost three departments around Paris, airports and ] stations, at an estimated cost of €35 billion.<ref name=metro>{{cite magazine |url=http://www.railwaygazette.com/news/single-view/view/EUR265bn-grand-paris-metro-expansion-programme-confirmed.html |title=€26.5bn Grand Paris metro expansion programme confirmed |date=12 March 2013 |access-date=24 April 2013 |magazine=Railway Gazette International |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130318205908/http://www.railwaygazette.com/news/single-view/view/EUR265bn-grand-paris-metro-expansion-programme-confirmed.html |archive-date=18 March 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> The system is scheduled to be completed by 2030.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.societedugrandparis.fr/#projet |title=Le Metro du Grand Paris |publisher=Site of Grand Paris Express |language=fr |access-date=27 November 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110714020412/http://www.societedugrandparis.fr/#projet |archive-date=14 July 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Paris during the 16th Century=== | |||

| ] (1532), the first Renaissance church in Paris]] | |||

| ] | |||

| By 1500, Paris had regained its old prosperity, and the population once again reached 250,000. ] rarely visited Paris, but he did finance grand construction projects, including rebuilding the old wooden Pont de Notre Dame, which had collapsed on 25 October 1499. The new bridge, opened in 1512, was made of and paved with stone, and lined with sixty-eight houses and shops.<ref>Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris'', p. 59</ref> On 15 July 1533 King ] laid the foundation stone the first ], the city hall of Paris, designed by his favourite Italian architect ], who also designed the ] in the Loire Valley for Francois. The Hotel de Ville was not finished until 1628.<ref>Combeau, Yvan, ''Histoire de Paris'', p. 35.</ref> Cortona also designed the first Renaissance church in Paris, the church of ], (1532) covering a gothic structure with flamboyant Renaissance detail and decoration. The first Renaissance house in Paris was the ], begun in 1545. It was modelled after the Grand Ferrare, a mansion in Fontainbleau designed by Italian architect Sebastiano Serlio. It is now the museum of the history of Paris.<ref>Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris'', p. 68-69</ref> | |||

| In January 2015, ] claimed ] across the Paris region.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.cnn.com/2015/01/21/europe/2015-paris-terror-attacks-fast-facts/index.html |title=2015 Charlie Hebdo Attacks Fast Facts |last=Library |first=C.N.N. |website=CNN |date=21 January 2015 |access-date=20 June 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170623154608/http://www.cnn.com/2015/01/21/europe/2015-paris-terror-attacks-fast-facts/index.html |archive-date=23 June 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2015/01/14/attentats-terroristes-les-questions-que-vous-nous-avez-le-plus-posees_4554653_4355770.html |work=Le Monde |date=15 January 2015 |access-date=15 January 2015 |title=Attentats terroristes : les questions que vous nous avez le plus posées |language=fr |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150114153341/http://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2015/01/14/attentats-terroristes-les-questions-que-vous-nous-avez-le-plus-posees_4554653_4355770.html |archive-date=14 January 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref> ] in a show of solidarity against terrorism and in support of freedom of speech.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.lefigaro.fr/politique/le-scan/citations/2015/01/11/25002-20150111ARTFIG00086-les-politiques-s-affichent-a-la-marche-republicaine.php |title=Les politiques s'affichent à la marche républicaine |work=Le Figaro |date=11 January 2015 |access-date=11 January 2015 |language=fr |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150111213532/http://www.lefigaro.fr/politique/le-scan/citations/2015/01/11/25002-20150111ARTFIG00086-les-politiques-s-affichent-a-la-marche-republicaine.php |archive-date=11 January 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref> In November of the same year, ], claimed by ISIL,<ref>{{Cite news |title=Islamic State claims Paris attacks that killed 127 |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-shooting-idUSKCN0T22IU20151114 |newspaper=Reuters |date=14 November 2015 |access-date=14 November 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151114014250/http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/11/14/us-france-shooting-idUSKCN0T22IU20151114 |archive-date=14 November 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref> killed 130 people and injured more than 350.<ref>{{Cite web |date=20 November 2015 |title=Paris attacks death toll rises to 130 |website=] |url=https://www.rte.ie/news/2015/1120/747897-paris/ |language=en |access-date=8 November 2021 |archive-date=23 April 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190423123908/https://www.rte.ie/news/2015/1120/747897-paris/ |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| In 1534 ] became the first French king to make the Louvre his residence; he demolished the massive central tower to create an open courtyard. Near the end of his reign Francois I decided to build a new wing with a Renaissance facade in place of one wing built by Philippe Auguste. The new wing was designed by ], and became a model for other Renaissance facades in France. | |||

| Francois I also reinforced the position of Paris as a centre of learning and scholarship. In 1500, there were seventy-five printing houses in Paris, second only to Venice; during the 16th century Paris became first in Europe in book publishing. In 1530, Francois I created a new faculty at the University of Paris with the mission of teaching Hebrew, Greek and mathematics. It became the ].<ref>Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris'', p. 68</ref> | |||

| On 22 April 2016, the ] was signed by 196 nations of the ] in an aim to limit the ] below 2 °C.<ref>{{cite web|date=22 April 2016|title='Today is an historic day,' says Ban, as 175 countries sign Paris climate accord|url=https://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=53756#.VxqAYGNpr-Y|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170629105154/http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=53756#.VxqAYGNpr-Y|archive-date=29 June 2017|access-date=26 June 2023|work=United Nations}}</ref> | |||

| ==Geography== | |||

| Francois I died in 1547, and his son, ], continued to decorate Paris in the French Renaissance style; the finest Renaissance fountain in the city, the ], was built to celebrate Henry's entrance into Paris in 1549. Henry II built a new wing for the Louvre, the ''Pavillon du Roi'', along the Seine. The bedroom of the King was on the first floor of this new wing. He also built a magnificent hall for festivities and ceremonies, the Salle des Cariatides, in the Lescot wing of the Louvre.<ref name="Sarmant, Thierry p. 71-72">Sarmant, Thierry, ''Histoire de Paris'', p. 71-72</ref> | |||

| ===Location=== | |||

| {{Main|Geography of Paris}} | |||

| ] mission]] | |||

| Paris is located in northern central France, in a north-bending arc of the river ], whose crest includes two islands, the ] and the larger ], which form the oldest part of Paris. The river's mouth on the ] (''La Manche'') is about {{cvt|233|mi}} downstream from Paris. Paris is spread widely on both banks of the river.<ref name=City>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/443621/Paris |title=Paris |access-date=4 July 2013 |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130707083834/https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/443621/Paris |archive-date=7 July 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> Overall, Paris is relatively flat, and the lowest point is {{cvt|35|m}} ]. Paris has several prominent hills, the highest of which is ] at {{cvt|130|m|ft|0}}.{{sfn|Blackmore|McConnachie|2004|p=153}} | |||

| Excluding the outlying parks of ] and ], Paris covers an oval measuring about {{cvt|87|km2}} in area, enclosed by the {{cvt|35|km|adj=on}} ring road, the ].{{sfn|Lawrence|Gondrand|2010|p=69}} Paris' last major annexation of outlying territories in 1860 gave it its modern form, and created the 20 clockwise-spiralling arrondissements (municipal boroughs). From the 1860 area of {{cvt|78|km2}}, the city limits were expanded marginally to {{cvt|86.9|km2}} in the 1920s. In 1929, the Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes forest parks were annexed to the city, bringing its area to about {{cvt|105|km2}}.<ref>{{cite web |website=Mairie de Paris |url=http://www.paris.fr/portail/english/Portal.lut?page_id=8125&document_type_id=5&document_id=29918&portlet_id=18748 |title=Key figures for Paris |publisher=Paris.fr |date=15 November 2007 |access-date=5 May 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090306220509/http://www.paris.fr/portail/english/Portal.lut?page_id=8125&document_type_id=5&document_id=29918&portlet_id=18748 |archive-date=6 March 2009}}</ref> The metropolitan area is {{cvt|2300|km2}}.<ref name=City/> | |||

| Henry II died 10 July 1559 from wounds suffered while jousting at his residence at the Hotel des Tournelles. His widow, ], | |||

| had the old residence demolished in 1563, and between 1564 and 1572 constructed a new royal residence, the ] perpendicular to the Seine, at what was then the edge of the city. To the west of the palace she created a large Italian style park, which became the ]. | |||