| Revision as of 21:05, 18 February 2006 view sourceSalman01 (talk | contribs)1,578 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 09:54, 10 January 2025 view source Wiqi55 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users7,573 editsm Fixing style/layout errors | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{pp-semi-indef|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Infobox Military Conflict| | |||

| {{Short description|629 AD battle in the Arab–Byzantine Wars}} | |||

| conflict=Battle of Mu'tah | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | |||

| |partof=the Byzantine-Arab Wars| | |||

| | conflict = Battle of Mu'tah<br>{{lang|ar|غَزْوَة مُؤْتَة}}<br>{{lang|ar|مَعْرَكَة مُؤْتَة}} | |||

| |image= | |||

| | partof = the ] | |||

| |caption= | |||

| | image = Mausoleum ,Jafer-ut-Tayyar,Jordan.JPG | |||

| |date=] ] | |||

| | caption = The tomb of Muslim commanders ], ], and ] in Al-Mazar near ], ] | |||

| |place=Near Ma'an, ] | |||

| | next_battle = ] | |||

| |result=Indecisive, Muslim ] | |||

| | date = September 629{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=72}} | |||

| |combatant1=Muslims | |||

| | place = ], ] | |||

| |combatant2=]<br>] ]s | |||

| | coordinates = {{WikidataCoord|display=it}} | |||

| |commander1=]<br>]<br>]<br>] | |||

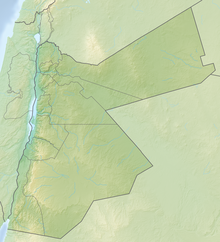

| | map_type = Jordan | |||

| |commander2=]<br>] | |||

| | map_relief = yes | |||

| |strength1=3,000 | |||

| | map_size = | |||

| |strength2=At least 15,000<br>possibly 200,000 | |||

| | map_marksize = | |||

| |casualties1=12 | |||

| | map_caption = | |||

| |casualties2=considerable | |||

| | map_label = | |||

| |}} | |||

| | map_mark = | |||

| {{Campaignbox Rise of Islam}} | |||

| | casus = | |||

| {{Campaignbox Byzantine-Arab}} | |||

| | territory = | |||

| | result = Byzantine victory{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=67}}{{sfn|Donner|1981|p=105}}{{sfn|Buhl|1993|p=756-757}} | |||

| | combatant1 = ] | |||

| | combatant2 = ]<br>] | |||

| | commander1 = ]{{KIA}}<br>]{{KIA}}<br>]{{KIA}}<br>] {{small|(unofficial)}} | |||

| | commander2 = ]<br>Mālik ibn Zāfila{{KIA}} | |||

| | strength1 = 3,000{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=86}} | |||

| | strength2 = 100,000 (])<ref name=waqidi>{{Cite book| publisher = Cambridge University Press| isbn = 978-0-521-59984-9| last = Gil| first = Moshe| title = A History of Palestine, 634-1099| url = https://archive.org/details/historypalestine00gilm| url-access = limited| date = 1997-02-27|page=}}</ref><br>200,000 (])<ref name=ishaq>{{Cite book| publisher = Oxford University Press, USA| isbn = 0-19-636033-1| last = Ibn Ishaq| others = A. Guillaume (trans.)| title = The Life of Muhammad| date = 2004|quote=They went on their way as far as Ma‘ān in Syria where they heard that Heraclius had come down to Ma’āb in the Balqāʾ with 100,000 Greeks joined by 100,000 men from Lakhm and Judhām and al-Qayn and Bahrāʾ and Balī commanded by a man of Balī of Irāsha called Mālik b. Zāfila. (p. 232) Quṭba b. Qatāda al-‘Udhrī who was over the right wing had attacked Mālik b. Zāfila (Ṭ. leader of the mixed Arabs) and killed him, (p. 236) | pages=532, 536}}</ref><br>{{small|(both exaggerated)}}{{sfn|Haldon|2010|p=188}}{{sfn|Peters|1994|p=231}}{{sfn|Buhl|1993|p=756-757}} | |||

| 10,000 or fewer {{small|(modern estimate)}}{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=79}} | |||

| | casualties1 = 12<ref name=zayd>{{Cite book| publisher = University of Pennsylvania Press| isbn = 978-0-8122-4617-9| last = Powers| first = David S.| title = Zayd| date = 2014-05-23|pages=58–9}}</ref> {{small|(Disputed)}}{{sfn|Peterson|2007|p=142}}{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=80}} | |||

| | casualties2 = Unknown | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Campaigns of Muhammad}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Arab–Byzantine Wars}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Campaigns of Khalid ibn Walid}} | |||

| The '''Battle of Mu'tah''' ({{langx|ar|مَعْرَكَة مُؤْتَة|translit=Maʿrakat Muʿtah}}, or {{langx|ar|غَزْوَة مُؤْتَة|link=no}} ''{{transl|ar|Ghazwat Muʿtah|link=no}}'') took place in September 629 (1 ] 8 ]),{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=72}} between the forces of ] and the army of the ] and their ] vassals. It took place in the village of ] in ] at the east of the ] and modern-day ]. | |||

| In Islamic historical sources, the battle is usually described as the Muslims' attempt to take retribution against a Ghassanid chief for taking the life of an emissary. According to Byzantine sources, the Muslims planned to launch their attack on a feast day. The local Byzantine ] learned of their plans and collected the garrisons of the fortresses. Seeing the great number of the enemy forces, the Muslims withdrew to the south where the fighting started at the village of Mu'tah and they were either routed or retired without exacting a penalty on the Ghassanid chief.<ref name=watt>{{Cite book| publisher = Oxford University Press| isbn = 978-0-353-30668-4| last = W| first = Montgomery Watt| title = Muhammad at Medina| date = 1956|pages=54–55, 342}}</ref>{{sfn|Buhl|1993|p=756-757}}{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=67}} According to Muslim sources, after three of their leaders were killed, the command was given to ] and he succeeded in saving the rest of the force.{{sfn|Buhl|1993|p=756-757}} | |||

| The most significant and the fiercest battle fought during Prophet ]'s lifetime was the Battle of Mutah (629 AD). It also took the lives of his closest companions, martyred fighting against a combined ]/Ghassanid army. You can visit the tombs of the venerable companions ], ], and ] in the town of Al-Mazar Al-Janubi near ]. | |||

| Three years later the Muslims would return to defeat the Byzantine forces in the ]. | |||

| Prophet Mohammad's adopted son, the venerable companion Zaid ibn Harithah led the Muslim army during the Battle of Mutah. Zaid fought in matchless spirit of bravery until he fell, fatally stabbed. He is the only companion mentioned in the Holy Qur'an by name : "Then when Zaid had dissolved (his marriage) with her, we joined her in marriage to thee: in order that (in future) there may be no difficulty to the Believers in (the matter of) marriage with the wives of their adopted sons, when the latter have dissolved (their marriage) with them. And Allah's command must be fulfilled". | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| The deputy commander of the army the venerable companion Ja'far ibn Abi Talib, cousin of Prophet Mohammad, then took the banner after Zaid. He is often known as "The Flying Ja'far" because he lost his hands during the battle and continued to hold the banner. Ja'far, was known to be similar to the Prophet both in features and in character. He was renowned for his kindness towards the needy and for narrating the hadiths directly from the Prophet. | |||

| The Byzantines were reoccupying territory following the peace accord between Emperor ] and the ] in July 629.{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=72-73}} The Byzantine '']'' ],{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=35}} was placed in command of the army, and while in the area of Balqa, Arab tribes were also employed.{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=72-73}} | |||

| Ja'far was charged with heading a group of Muslims who migrated to Abyssinia (Ethiopia). The non-believers sent a delegation headed by Amr ibn Al-Aas to bring the Muslims back to Mecca. A debate took place in the presence of the King of Abyssinia where Ja'far proved to be indomitable and unflinching in elaborating the Muslim viewpoint. | |||

| Meanwhile, Muhammad had sent his emissary to the ruler of Bostra.{{sfn|El Hareir|M'Baye|2011|p=142}} While on his way to Bostra, he was executed in the village of Mu'tah by the orders of a Ghassanid official ].{{sfn|El Hareir|M'Baye|2011|p=142}} | |||

| When the King asked him about Prophet Mohammad's opinion of Jesus the son of Mary, Ja'far wisely answered: "I will tell you what Prophet Mohammad says about Jesus based on the words of Allah: ''Jesus is the spirit and word of Allah who revealed it to Mary the Pious Virgin". Content with the reply, the King of Abyssinia allowed the Muslims to stay.'' | |||

| ==Mobilization of the armies== | |||

| The venerable companion Abdullah ibn Ruwahah, the third in charge of the army after Zaid and Ja'far, then assumed command. Abdullah was known among the companions for his piety, obedience and patience. Furthermore, he was a faithful and selflessly dedicated soldier. He was a famous poet of his time, and became the Prophet's poet. Before being martyred in the Battle of Mutah, Abdullah said the following lines as his army faced an overwhelming number of Byzantine and Ghassanid Arab troops: | |||

| Muhammad dispatched 3,000 of his troops in the month of ] 7 (AH), 629 (CE), for a quick expedition to attack and punish the tribes for the murder of his emissary by the Ghassanids.{{sfn|El Hareir|M'Baye|2011|p=142}} The army was led by ]; the second-in-command was ] and the third-in-command was ].<ref name="zayd" /> When the Muslim troops arrived at the area to the east of Jordan and learned of the size of the Byzantine army, they wanted to wait and send for reinforcements from ]. 'Abdullah ibn Rawahah reminded them about their desire for martyrdom and questioned the move to wait when what they desire was awaiting them, so they continued marching towards the waiting army. | |||

| ''"O my soul! If you are not killed, you are bound to die anyway. This is the fate of death overtaking you. What you have wished for, you have been granted. If you do what they (Zaid and Ja'far) have done. Then you are rightly guided".'' | |||

| ==Battle== | |||

| The Muslims engaged the Byzantines at their camp by the village of Musharif and then withdrew towards Mu'tah. It was here that the two armies fought. Some Muslim sources report that the battle was fought in a valley between two heights, which negated the Byzantines' numerical superiority. During the battle, all three Muslim leaders fell one after the other as they took command of the force: first, Zayd, then Ja'far, then 'Abdullah. The leader of the Arab vassal forces, Mālik ibn Zāfila, was also killed in battle.<ref name=ishaq /> After the death of 'Abdullah, the Muslim soldiers were in danger of being routed. Thabit ibn Aqram, seeing the desperate state of the Muslim forces, took up the banner and rallied his comrades, thus saving the army from complete destruction. After the battle, ibn Aqram took the banner, before asking ] to take the lead.<ref name="Al-Islam Ja'far">{{citation |publisher=] |title=Jafar al-Tayyar |url=http://www.al-islam.org/jafar-al-tayyar-kamal-al-sayyid/jafar-al-tayyar/ }}</ref> | |||

| In and around Kerak other shrines of significance to Islam are located. You can visit Prophet Nuh 'Noah' shrine in the city of Kerak. Allah sent Noah to his people to warn them of divine punishment if they continued to worship idols. As stated in the Holy Qur'an in a Sura entitled Noah (Sura 71, verses 1-3): "We sent Noah to his People (with the Command): Do thou warn thy People before there comes to them a grievous Chastisement. He said: O my People! I am to you a Warner, clear and open: That ye should worship Allah, fear Him and obey me". | |||

| ==Muslim losses== | |||

| Credited with great wisdom and piety, the Prophet and King of Israel, Sulayman 'Solomon', has a shrine in Sarfah near Kerak. Prophet Solomon had great powers that included control over the winds, over the Jinnis and understanding the language of birds and other animals. Islam regards Solomon as impeccable like his father Prophet and King Dawud 'David'. Prophet Solomon is mentioned in 16 verses in the Holy Qur'an. | |||

| Four of the slain Muslims were ] (early Muslim converts who emigrated from Mecca to Medina) and eight were from the ] (early Muslim converts native to Medina). Those slain Muslims named in the sources were ], ], ], Mas'ud ibn al-Aswad, ], Abbad ibn Qays, Amr ibn Sa'd, Harith ibn Nu'man, Suraqa ibn Amr, Abu Kulayb ibn Amr, Jabir ibn Amr and Amir ibn Sa'd. | |||

| Also in Kerak is the shrine of Zaid ibn Ali ibn Al-Hussein. He was the great, great, grandson of Prophet Mohammad, and a religious leader known for his righteous, majestic and knowledgeable ways. When describing Zaid, Al-Imam Ja'far Al-Sadiq said: "Among us he was the best read in the Holy Qur'an, and the most knowledgeable about religion, and the most caring towards family and relatives". | |||

| Daniel C. Peterson, Professor of Islamic Studies at Brigham Young University, finds the ratio of casualties among the leaders suspiciously high compared to the losses suffered by ordinary soldiers.{{sfn|Peterson|2007|p=142}} David Powers, Professor of Near Eastern Studies at Cornell, also mentions this curiosity concerning the minuscule casualties recorded by Muslim historians.{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=80}} ] argues that a low casualty count is possible if the nature of this encounter was a ] or if the Muslims completely routed the enemy.<ref name=watt /> He further notes that the discrepancy between leaders and ordinary soldiers is not inconceivable in view of Arab fighting methods.<ref name=watt /> | |||

| ==Aftermath== | |||

| After the Muslim forces arrived at Medina, they were reportedly berated for withdrawing and accused of fleeing.{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=81}} Salamah ibn Hisham, brother of ] (Abu Jahl) was reported to have prayed at home rather than going to the mosque to avoid having to explain himself. Muhammad ordered them to stop, saying that they would return to fight the Byzantines again.{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=81}} According to Watt, most of these accounts were intended to vilify Khalid and his decision to return to Medina, as well as to glorify the part played by members of one's family.<ref name=watt /> It would not be until the third century AH that Sunni Muslim historians would state that Muhammad bestowed upon Khalid the title of 'Saifullah' meaning 'Sword of Allah'.{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=80}} | |||

| Today, Muslims who fell at the battle are considered ]s ('']''). A ] was later built at Mu'tah over their graves.{{sfn|Buhl|1993|p=756-757}} | |||

| ==Historiography== | |||

| ] | |||

| According to ] (d. 823) and ] (d. 767), the Muslims were informed that 100,000<ref name=waqidi /> or 200,000<ref name=ishaq/> enemy troops were encamped at the ]'.<ref name=waqidi />{{sfn|Haykal|1976|p=419}} Some modern historians state that the figure is exaggerated.{{sfn|Haldon|2010|p=188}}{{sfn|Peters|1994|p=231}}{{sfn|Buhl|1993|p=756-757}} According to Walter Emil Kaegi, professor of Byzantine history at the ], the size of the entire Byzantine army during the 7th century might have totaled 100,000, possibly even half this number.{{sfn|Kaegi|2010|p=99}} While the Byzantine forces at Mu'tah are unlikely to have numbered more than 10,000.{{efn|The Byzantines do not appear to have used many Greek, Armenian, or other non-Arab soldiers at Mu'ta, even though the overall commander was the ''vicarius'' Theodore. The number that the Byzantines raised are, of course, uncertain, but unlikely to have exceeded 10,000.{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=79}}}}{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=79}} | |||

| Muslim accounts of the battle differ over the result.{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=80}} According to David S. Powers, the earliest Muslim sources like al-Waqidi record the battle as a humiliating defeat (''hazīma'').{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=80}} However, ] notes that al-Waqidi also recorded an account where the Byzantine forces fled.<ref name=watt /> Powers suggests that later Muslim historians reworked the early source material to reflect the Islamic view of God's plan.{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=80}} Subsequent sources present the battle as a Muslim victory given that most of the Muslim soldiers returned safely.{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=80}} | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| == |

==Notes== | ||

| {{Notelist}} | |||

| * | |||

| *http://al-islam.org/restatement/30.htm | |||

| *http://www.islamanswers.net/moreAbout/Muta.htm | |||

| *http://www.swordofallah.com/html/bookchapter6page1.htm | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{Islam-stub}} | |||

| {{ |

{{Reflist}} | ||

| ==Sources== | |||

| ] | |||

| *{{cite book |first=Fred M. |last=Donner |author-link=Fred M. Donner |year=1981 |title=The Early Islamic Conquests |publisher=Princeton University Press }} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=The Different Aspects of Islam Culture: Volume 3, The Spread of Islam throughout the World |last1=El Hareir |first1=Idris |last2=M'Baye |first2=El Hadji Ravane |publisher=UNESCO publishing |year=2011 }} | |||

| *{{Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition|volume=7|title=Muʾta|last=Buhl |first=F.|author-link=|pages=756}} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Money, Power and Politics in Early Islamic Syria |last=Haldon |first=John |author-link=John Haldon |publisher=Ashgate Publishing |year=2010 }} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=The Life of Muhammad |last=Haykal |first=Muhammad |publisher=Islamic Book Trust |year=1976 }} | |||

| *{{Cite book| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=IvPVEb17uzkC| title = Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests| last = Kaegi| first = Walter E. |author-link=Walter Kaegi | publisher = Cambridge University Press| year = 1992| isbn = 978-0521411721|location = Cambridge}} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Muslim Expansion and Byzantine Collapse in North Africa |last=Kaegi |first=Walter E. |author-link=Walter Kaegi |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2010 |isbn=978-0-521-19677-2 }} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Muhammad and the Origins of Islam |url=https://archive.org/details/muhammadorigins00pete |url-access=registration |last=Peters |first=Francis E. |publisher=State University of New York Press |year=1994 }} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Muhammad, Prophet of God |last=Peterson |first=Daniel C. |publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. |year=2007 }} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Muhammad Is Not the Father of Any of Your Men: The Making of the Last Prophet |last=Powers |first=David S. |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |year=2009 |isbn=9780812205572 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KH2FUBSOQ8kC }} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=A Global Chronology of Conflict |volume=I |editor-last=Tucker |editor-first=Spencer |editor-link= Spencer C. Tucker |publisher=ABC-CLIO |year=2010 }} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Commons category}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 09:54, 10 January 2025

629 AD battle in the Arab–Byzantine Wars

| Battle of Mu'tah غَزْوَة مُؤْتَة مَعْرَكَة مُؤْتَة | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab–Byzantine wars | |||||||

The tomb of Muslim commanders Zayd ibn Haritha, Ja'far ibn Abi Talib, and Abd Allah ibn Rawahah in Al-Mazar near Mu'tah, Jordan | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Muslim Arabs |

Byzantine Empire Ghassanids | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Zayd ibn Haritha † Ja'far ibn Abi Talib † Abd Allah ibn Rawaha † Khalid ibn al-Walid (unofficial) |

Theodore Mālik ibn Zāfila † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,000 | 10,000 or fewer (modern estimate) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 12 (Disputed) | Unknown | ||||||

| |||||||

| Campaigns of Muhammad | |

|---|---|

| Further information: Military career of Muhammad |

| Arab–Byzantine wars | |

|---|---|

Early conflicts

Border conflicts

Sicily and Southern Italy

Naval warfare

Byzantine reconquest

|

| Campaigns of Khalid ibn al-Walid | |

|---|---|

Campaigns under Muhammad

|

The Battle of Mu'tah (Arabic: مَعْرَكَة مُؤْتَة, romanized: Maʿrakat Muʿtah, or Arabic: غَزْوَة مُؤْتَة Ghazwat Muʿtah) took place in September 629 (1 Jumada al-Awwal 8 AH), between the forces of Muhammad and the army of the Byzantine Empire and their Ghassanid vassals. It took place in the village of Mu'tah in Palaestina Salutaris at the east of the Jordan River and modern-day Karak.

In Islamic historical sources, the battle is usually described as the Muslims' attempt to take retribution against a Ghassanid chief for taking the life of an emissary. According to Byzantine sources, the Muslims planned to launch their attack on a feast day. The local Byzantine Vicarius learned of their plans and collected the garrisons of the fortresses. Seeing the great number of the enemy forces, the Muslims withdrew to the south where the fighting started at the village of Mu'tah and they were either routed or retired without exacting a penalty on the Ghassanid chief. According to Muslim sources, after three of their leaders were killed, the command was given to Khalid ibn al-Walid and he succeeded in saving the rest of the force.

Three years later the Muslims would return to defeat the Byzantine forces in the Expedition of Usama bin Zayd.

Background

The Byzantines were reoccupying territory following the peace accord between Emperor Heraclius and the Sasanid general Shahrbaraz in July 629. The Byzantine sakellarios Theodore, was placed in command of the army, and while in the area of Balqa, Arab tribes were also employed.

Meanwhile, Muhammad had sent his emissary to the ruler of Bostra. While on his way to Bostra, he was executed in the village of Mu'tah by the orders of a Ghassanid official Shurahbil ibn Amr.

Mobilization of the armies

Muhammad dispatched 3,000 of his troops in the month of Jumada al-Awwal 7 (AH), 629 (CE), for a quick expedition to attack and punish the tribes for the murder of his emissary by the Ghassanids. The army was led by Zayd ibn Harithah; the second-in-command was Ja'far ibn Abi Talib and the third-in-command was Abd Allah ibn Rawahah. When the Muslim troops arrived at the area to the east of Jordan and learned of the size of the Byzantine army, they wanted to wait and send for reinforcements from Medina. 'Abdullah ibn Rawahah reminded them about their desire for martyrdom and questioned the move to wait when what they desire was awaiting them, so they continued marching towards the waiting army.

Battle

The Muslims engaged the Byzantines at their camp by the village of Musharif and then withdrew towards Mu'tah. It was here that the two armies fought. Some Muslim sources report that the battle was fought in a valley between two heights, which negated the Byzantines' numerical superiority. During the battle, all three Muslim leaders fell one after the other as they took command of the force: first, Zayd, then Ja'far, then 'Abdullah. The leader of the Arab vassal forces, Mālik ibn Zāfila, was also killed in battle. After the death of 'Abdullah, the Muslim soldiers were in danger of being routed. Thabit ibn Aqram, seeing the desperate state of the Muslim forces, took up the banner and rallied his comrades, thus saving the army from complete destruction. After the battle, ibn Aqram took the banner, before asking Khalid ibn al-Walid to take the lead.

Muslim losses

Four of the slain Muslims were Muhajirin (early Muslim converts who emigrated from Mecca to Medina) and eight were from the Ansar (early Muslim converts native to Medina). Those slain Muslims named in the sources were Zayd ibn Haritha, Ja'far ibn Abi Talib, Abd Allah ibn Rawaha, Mas'ud ibn al-Aswad, Wahb ibn Sa'd, Abbad ibn Qays, Amr ibn Sa'd, Harith ibn Nu'man, Suraqa ibn Amr, Abu Kulayb ibn Amr, Jabir ibn Amr and Amir ibn Sa'd.

Daniel C. Peterson, Professor of Islamic Studies at Brigham Young University, finds the ratio of casualties among the leaders suspiciously high compared to the losses suffered by ordinary soldiers. David Powers, Professor of Near Eastern Studies at Cornell, also mentions this curiosity concerning the minuscule casualties recorded by Muslim historians. Montgomery Watt argues that a low casualty count is possible if the nature of this encounter was a skirmish or if the Muslims completely routed the enemy. He further notes that the discrepancy between leaders and ordinary soldiers is not inconceivable in view of Arab fighting methods.

Aftermath

After the Muslim forces arrived at Medina, they were reportedly berated for withdrawing and accused of fleeing. Salamah ibn Hisham, brother of Amr ibn Hishām (Abu Jahl) was reported to have prayed at home rather than going to the mosque to avoid having to explain himself. Muhammad ordered them to stop, saying that they would return to fight the Byzantines again. According to Watt, most of these accounts were intended to vilify Khalid and his decision to return to Medina, as well as to glorify the part played by members of one's family. It would not be until the third century AH that Sunni Muslim historians would state that Muhammad bestowed upon Khalid the title of 'Saifullah' meaning 'Sword of Allah'.

Today, Muslims who fell at the battle are considered martyrs (shuhadāʾ). A mausoleum was later built at Mu'tah over their graves.

Historiography

According to al-Waqidi (d. 823) and Ibn Ishaq (d. 767), the Muslims were informed that 100,000 or 200,000 enemy troops were encamped at the Balqa'. Some modern historians state that the figure is exaggerated. According to Walter Emil Kaegi, professor of Byzantine history at the University of Chicago, the size of the entire Byzantine army during the 7th century might have totaled 100,000, possibly even half this number. While the Byzantine forces at Mu'tah are unlikely to have numbered more than 10,000.

Muslim accounts of the battle differ over the result. According to David S. Powers, the earliest Muslim sources like al-Waqidi record the battle as a humiliating defeat (hazīma). However, Montgomery Watt notes that al-Waqidi also recorded an account where the Byzantine forces fled. Powers suggests that later Muslim historians reworked the early source material to reflect the Islamic view of God's plan. Subsequent sources present the battle as a Muslim victory given that most of the Muslim soldiers returned safely.

See also

- Military career of Muhammad

- List of expeditions of Muhammad

- History of Islam

- Jihad

- Muhammad's views on Christians

Notes

- The Byzantines do not appear to have used many Greek, Armenian, or other non-Arab soldiers at Mu'ta, even though the overall commander was the vicarius Theodore. The number that the Byzantines raised are, of course, uncertain, but unlikely to have exceeded 10,000.

References

- ^ Kaegi 1992, p. 72.

- ^ Kaegi 1992, p. 67.

- Donner 1981, p. 105.

- ^ Buhl 1993, p. 756-757.

- Powers 2009, p. 86.

- ^ Gil, Moshe (1997-02-27). A History of Palestine, 634-1099. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-521-59984-9.

- ^ Ibn Ishaq (2004). The Life of Muhammad. A. Guillaume (trans.). Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 532, 536. ISBN 0-19-636033-1.

They went on their way as far as Ma'ān in Syria where they heard that Heraclius had come down to Ma'āb in the Balqāʾ with 100,000 Greeks joined by 100,000 men from Lakhm and Judhām and al-Qayn and Bahrāʾ and Balī commanded by a man of Balī of Irāsha called Mālik b. Zāfila. (p. 232) Quṭba b. Qatāda al-'Udhrī who was over the right wing had attacked Mālik b. Zāfila (Ṭ. leader of the mixed Arabs) and killed him, (p. 236)

- ^ Haldon 2010, p. 188.

- ^ Peters 1994, p. 231.

- ^ Kaegi 1992, p. 79.

- ^ Powers, David S. (2014-05-23). Zayd. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 58–9. ISBN 978-0-8122-4617-9.

- ^ Peterson 2007, p. 142.

- ^ Powers 2009, p. 80.

- ^ W, Montgomery Watt (1956). Muhammad at Medina. Oxford University Press. pp. 54–55, 342. ISBN 978-0-353-30668-4.

- ^ Kaegi 1992, p. 72-73.

- Kaegi 1992, p. 35.

- ^ El Hareir & M'Baye 2011, p. 142.

- Jafar al-Tayyar, Al-Islam.org

- ^ Powers 2009, p. 81.

- Haykal 1976, p. 419.

- Kaegi 2010, p. 99.

Sources

- Donner, Fred M. (1981). The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton University Press.

- El Hareir, Idris; M'Baye, El Hadji Ravane (2011). The Different Aspects of Islam Culture: Volume 3, The Spread of Islam throughout the World. UNESCO publishing.

- Buhl, F. (1993). "Muʾta". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 756. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Haldon, John (2010). Money, Power and Politics in Early Islamic Syria. Ashgate Publishing.

- Haykal, Muhammad (1976). The Life of Muhammad. Islamic Book Trust.

- Kaegi, Walter E. (1992). Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521411721.

- Kaegi, Walter E. (2010). Muslim Expansion and Byzantine Collapse in North Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19677-2.

- Peters, Francis E. (1994). Muhammad and the Origins of Islam. State University of New York Press.

- Peterson, Daniel C. (2007). Muhammad, Prophet of God. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

- Powers, David S. (2009). Muhammad Is Not the Father of Any of Your Men: The Making of the Last Prophet. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812205572.

- Tucker, Spencer, ed. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict. Vol. I. ABC-CLIO.