| Revision as of 16:36, 2 December 2017 editImagination dragons (talk | contribs)7 edits Removed inappropriate contentTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 07:41, 11 January 2025 edit undoEarthDude (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,671 edits →Further reading: Added a book to further readingTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Economic system based on private ownership}} | |||

| Screw you capitalist pigs | |||

| {{About|an economic system}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Capitalist|other uses|Capitalist (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Pp-pc|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use American English|date=January 2014}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=June 2020}} | |||

| {{Capitalism sidebar}} | |||

| {{Economics sidebar}} | |||

| {{Economic systems sidebar|expanded=by ideology}} | |||

| {{Liberalism sidebar}} | |||

| {{Neoliberalism sidebar}} | |||

| '''Capitalism''' is an ] based on the ] of the ] and their operation for ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Zimbalist |last2=Sherman |last3=Brown |first1=Andrew |first2=Howard J. |first3=Stuart |title=Comparing Economic Systems: A Political-Economic Approach |publisher=] |date=October 1988 |isbn=978-0-15-512403-5 |pages= |quote=Pure capitalism is defined as a system wherein all of the means of production (physical capital) are privately owned and run by the capitalist class for a profit, while most other people are workers who work for a salary or wage (and who do not own the capital or the product). |url=https://archive.org/details/comparingeconomi0000zimb_q8i6/page/6}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Rosser |first1=Mariana V. |last2=Rosser |first2=J Barkley |title=Comparative Economics in a Transforming World Economy |publisher=] |date=23 July 2003 |isbn=978-0-262-18234-8 |page=7 |quote=In capitalist economies, land and produced means of production (the capital stock) are owned by private individuals or groups of private individuals organized as firms.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |first=Chris |last=Jenks |title=Core Sociological Dichotomies |quote=Capitalism, as a mode of production, is an economic system of manufacture and exchange which is geared toward the production and sale of commodities within a market for profit, where the manufacture of commodities consists of the use of the formally free labor of workers in exchange for a wage to create commodities in which the manufacturer extracts surplus value from the labor of the workers in terms of the difference between the wages paid to the worker and the value of the commodity produced by him/her to generate that profit. |location=London; Thousand Oaks, CA; New Delhi |publisher=] |page=383}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=The Challenge of Global Capitalism : The World Economy in the 21st Century |last=Gilpin |first=Robert |author-link=Robert Gilpin |isbn=978-0-691-18647-4 |oclc=1076397003 |date=2018|publisher=Princeton University Press }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sternberg |first1=Elaine |title=Defining Capitalism |journal=] |date=2015 |volume=35 |issue=3 |pages=380–396 |doi=10.1111/ecaf.12141|s2cid=219373247 | issn = 0265-0665}}</ref> The defining characteristics of capitalism include ], ], ]s, ]s, recognition of ], ], ], ], ], ], ], a ] that makes possible ] and ], ], ], ], ], production of ] and ]s, and a strong emphasis on ] and ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Heilbroner |first1=Robert L. |title=The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics |date=2018 |publisher=] |location=London |isbn=978-1-349-95189-5 |pages=1378–1389 |chapter-url=https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_154 |language=en |chapter=Capitalism |doi=10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_154}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Hodgson |first1=Geoffrey M. |title=Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future |date=2015 |publisher=] |location=Chicago |isbn=9780226168142 |url=https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo18523749.html}}</ref><ref name = "harris">{{cite journal |last1=Harris |first1=Neal |last2=Delanty |first2=Gerard |title=What is capitalism? Toward a working definition |journal=] |date=2023 |volume=62 |issue=3 |pages=323–344 |doi=10.1177/05390184231203878 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Berend |first1=Ivan T. |title=Capitalism |journal=] |date=2015 |pages=94–98 |doi=10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.62003-2|isbn=978-0-08-097087-5 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Antonio |first1=Robert J. |last2=Bonanno |first2=Alessandro |title=Capitalism |journal=The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization |date=2012 |doi=10.1002/9780470670590.wbeog060|isbn=978-1-4051-8824-1 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Beamish |first1=Rob |chapter=Capitalism |title=Core Concepts in Sociology |date=2018 |pages=17–22 |doi=10.1002/9781394260331.ch6|isbn=978-1-119-16861-4 }}</ref> In a ], decision-making and investments are determined by owners of wealth, property, or ability to maneuver capital or production ability in ] and ]s—whereas prices and the distribution of goods and services are mainly determined by competition in goods and services markets.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Gregory |first1=Paul |last2=Stuart |first2=Robert |year=2013 |title=The Global Economy and its Economic Systems |publisher=] |page=41 |isbn=978-1-285-05535-0 |quote=Capitalism is characterized by private ownership of the factors of production. Decision making is decentralized and rests with the owners of the factors of production. Their decision making is coordinated by the market, which provides the necessary information. Material incentives are used to motivate participants.}}</ref> | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| {|class="box" style="float: right; margin-left: 1em; text-align: left; border: 4px solid #aaa; padding: 2px; font-size: 100%; width: 30%;" | |||

| |- | |||

| |style="background:#dbeaff;"|Other terms sometimes used for capitalism: | |||

| * ]<ref>{{cite book|last=Mandel|first=Ernst|authorlink=Ernst Mandel|title=An Introduction to Marxist Economic Theory|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Pf9Jd1sIMJ0C&pg=PA24|accessdate=29 January 2017|year=2002|publisher=Resistance Books|isbn=978-1-876646-30-1|page=24}}</ref> | |||

| * ]<ref>{{cite journal |title=Adam Smith and His Legacy for Modern Capitalism|author=Werhane, P. H.|journal=The Review of Metaphysics|volume=47|year=1994|publisher=Philosophy Education Society|issue=3}}</ref> | |||

| * Free enterprise<ref name="rogetfreeenterprise">"Free enterprise". Roget's 21st Century Thesaurus, Third Edition. Philip Lief Group 2008.</ref> | |||

| * Free enterprise economy<ref name="britannica"/> | |||

| * ]<ref name="rogetfreeenterprise"/><ref name="mutualist">. "... based on voluntary cooperation, free exchange, or mutual aid."</ref> | |||

| * Free market economy<ref name="britannica"/> | |||

| * '']''<ref name=Barrons>Barrons Dictionary of Finance and Investment Terms, 1995; p. 74.</ref> | |||

| * ] <ref>, Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary</ref> | |||

| * ] <ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cato.org/about.php |title=About Cato |publisher=Cato Institute • www.cato.org |accessdate=6 November 2008}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cato.org/university/module10.html |title=The Achievements of Nineteenth-Century Classical Liberalism |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20090211160820/http://www.cato.org/university/module10.html |archivedate=11 February 2009 }} {{quote|Although the term "liberalism" retains its original meaning in most of the world, it has unfortunately come to have a very different meaning in late twentieth-century America. Hence terms such as "market liberalism," "classical liberalism," or "libertarianism" are often used in its place in America.}}</ref> | |||

| * ]<ref name="Duménil" /> | |||

| * Self-regulating market <ref name="rogetfreeenterprise" /> | |||

| * Profits system<ref>{{cite book |last= Shutt|first= Harry|title= Beyond the Profits System: Possibilities for the Post-Capitalist Era |publisher= Zed Books|year= 2010|isbn= 1-84813-417-7}}</ref> | |||

| |} | |||

| The term "capitalist", meaning an owner of ], appears earlier than the term "capitalism" and it dates back to the mid-17th century. "Capitalism" is derived from ''capital'', which evolved from ''capitale'', a late ] word based on ''caput'', meaning "head"{{snd}}also the origin of '']'' and '']'' in the sense of movable property (only much later to refer only to livestock). ''Capitale'' emerged in the 12th to 13th centuries in the sense of referring to funds, stock of merchandise, sum of money or money carrying interest.<ref name="Braudel on capitalism232">Braudel p. 232</ref><ref>{{OEtymD|cattle}}</ref><ref name="OED-93">James Augustus Henry Murray. "Capital". . ''Oxford English Press''. {{abbr|Vol.|Volume}} 2. p. 93.</ref> By 1283, it was used in the sense of the capital assets of a trading firm and it was frequently interchanged with a number of other words{{snd}}wealth, money, funds, goods, assets, property and so on.<ref name="Braudel on capitalism233">Braudel p. 233</ref> | |||

| Economists, historians, political economists, and sociologists have adopted different perspectives in their analyses of capitalism and have recognized various forms of it in practice. These include '']'' or ], ], ], and ]. Different ] feature varying degrees of ]s, ],<ref name="gregorystuart">{{cite book|last1=Gregory |first1=Paul |last2=Stuart |first2=Robert |title=The Global Economy and its Economic Systems |publisher=] |date=2013 |isbn=978-1-285-05535-0 |page=107 |quote=Real-world capitalist systems are mixed, some having higher shares of public ownership than others. The mix changes when privatization or nationalization occurs. Privatization is when property that had been state-owned is transferred to private owners. ] occurs when privately owned property becomes publicly owned.}}</ref> obstacles to free competition, and state-sanctioned ]. The degree of ] in ] and the role of ] and ], as well as the scope of state ownership, vary across different models of capitalism.<ref name="Modern Economics 1986, p. 54">{{cite book |title=Macmillan Dictionary of Modern Economics |edition=3rd |date=1986 |pages=54}}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine |last=Bronk |first=Richard |title=Which model of capitalism?|url=http://oecdobserver.org/news/archivestory.php/aid/345/Which_model_of_capitalism_.html |url-status=live |magazine=] |publisher=] |date=Summer 2000 |volume=1999 |issue=221–222 |pages=12–15 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180406200423/http://oecdobserver.org/news/archivestory.php/aid/345/Which_model_of_capitalism_.html |archive-date=6 April 2018 |access-date=6 April 2018}}</ref> The extent to which different markets are free and the rules defining private property are matters of politics and policy. Most of the existing capitalist economies are ] that combine elements of free markets with state intervention and in some cases ].<ref name="Stilwell">{{cite book |last=Stilwell |first=Frank |author-link=Frank Stilwell (economist) |title=Political Economy: the Contest of Economic Ideas |edition=1st |publisher=] |location=Melbourne, Australia |date=2002}}</ref> | |||

| The ''Hollandische Mercurius'' uses ''capitalists'' in 1633 and 1654 to refer to owners of capital.<ref name="Braudel on capitalism234">Braudel p. 234</ref> In French, ] referred to ''capitalistes'' in 1788,<ref>E.g., "L'Angleterre a-t-elle l'heureux privilège de n'avoir ni Agioteurs, ni Banquiers, ni Faiseurs de services, ni Capitalistes ?" in (1788) ''De la foi publique envers les créanciers de l'état : lettres à M. Linguet sur le n° CXVI de ses annales'' </ref> six years before its first recorded English usage by ] in his work ''Travels in France'' (1792).<ref name="OED-93" /><ref>Arthur Young. .</ref> In his '']'' (1817), ] referred to "the capitalist" many times.<ref>Ricardo, David. Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. 1821. John Murray Publisher, 3rd edition.</ref> ], an English poet, used "capitalist" in his work ''Table Talk'' (1823).<ref>Samuel Taylor Coleridge. . p. 267.</ref> ] used the term "capitalist" in his first work, '']'' (1840), to refer to the owners of capital. ] used the term "capitalist" in his 1845 work '']''.<ref name="OED-93" /> | |||

| Capitalism in its modern form emerged from ] in ], as well as ] practices by European countries between the 16th and 18th centuries. The Industrial Revolution of the 18th century established ], characterized by ], and a complex ]. Through the process of ], capitalism spread across the world in the 19th and 20th centuries, especially before World War I and after the end of the Cold War. During the 19th century, capitalism was largely unregulated by the state, but became more regulated in the post–] period through ], followed by a return of more unregulated capitalism starting in the 1980s through ]. | |||

| The initial usage of the term "capitalism" in its modern sense has been attributed to ] in 1850 ("What I call 'capitalism' that is to say the appropriation of capital by some to the exclusion of others") and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in 1861 ("Economic and social regime in which capital, the source of income, does not generally belong to those who make it work through their labour").<ref>Braudel, Fernand. ''The Wheels of Commerce: Civilization and Capitalism 15th–18th Century'', Harper and Row, 1979, p. 237.</ref> ] and ] referred to the "capitalistic system"<ref>Karl Marx. Chapter 16: "Absolute and Relative Surplus-Value." '']'': "The prolongation of the working-day beyond the point at which the laborer would have produced just an equivalent for the value of his labor-power, and the appropriation of that surplus-labor by capital, this is production of absolute surplus-value. It forms the general groundwork of the ''capitalist system'', and the starting-point for the production of relative surplus-value."</ref><ref>Karl Marx. Chapter Twenty-Five: "The General Law of Capitalist Accumulation". ''Das Kapital''.</ref> and to the "capitalist mode of production" in '']'' (1867).<ref>Saunders, Peter (1995). ''Capitalism''. University of Minnesota Press. P. 1.</ref> The use of the word "capitalism" in reference to an economic system appears twice in Volume I of ''The Capital'', p. 124 (German edition) and in ''Theories of Surplus Value'', tome II, p. 493 (German edition). Marx did not extensively use the form capitalism, but instead those of capitalist and capitalist mode of production'','' which appear more than 2,600 times in the trilogy The ''Capital.'' According to the '']'' (OED), the term "capitalism" first appeared in English in 1854 in the novel '']'' by novelist ], where he meant "having ownership of capital".<ref name="OED-94">James Augustus Henry Murray. "Capitalism" p. 94.</ref> Also according to the OED, ], a ] ] and ], used the phrase "private capitalism" in 1863. | |||

| The existence of market economies has been observed under many ] and across a vast array of ], ]s, and cultural contexts. The modern industrial capitalist societies that exist today developed in Western Europe as a result of the Industrial Revolution. The accumulation of capital is the primary mechanism through which capitalist economies promote ]. However, it is a characteristic of such economies that they experience a ] of ] followed by recessions.<ref name = "HP">{{cite journal |last1=Hodrick |first1=R. |last2=Prescott|first2= E. |year=1997 |title=Postwar US business cycles: An empirical investigation |journal=Journal of Money, Credit and Banking|volume=29|issue=1 |pages=1–16|doi=10.2307/2953682 |jstor=2953682 |s2cid=154995815 | url = http://www.kellogg.northwestern.edu/research/math/papers/451.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| == History == | |||

| {{Main article|History of capitalism}} | |||

| ] has existed incipiently on a small scale for centuries,<ref name="WarburtonDavid">Warburton, David. ''Macroeconomics from the beginning: The General Theory, Ancient Markets, and the Rate of Interest''. Paris, Recherches et Publications, 2003. p. 49.</ref> in the form of merchant, renting and lending activities, and occasionally as small-scale industry with some wage labour. Simple ] exchange, and consequently simple commodity production, which are the initial basis for the growth of capital from trade, have a very long history. The "capitalistic era" according to Karl Marx dates from 16th century merchants and small urban workshops.<ref name=GSGB>{{cite web|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Pf9Jd1sIMJ0C|title=An Introduction to Marxist Economic Theory|date=1 January 2002|publisher=Resistance Books|via=Google Books}}</ref> Marx knew that wage labour existed on a modest scale for centuries before capitalist industry. Early Islam promulgated capitalist economic policies, which migrated to Europe through trade partners from cities such as Venice.<ref name="Koehler, Benedikt">Koehler, Benedikt. ''Early Islam and the Birth of Capitalism'' (Lexington Books, 2014).</ref> Capitalism in its modern form can be traced to the emergence of agrarian capitalism and mercantilism in the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.economist.com/node/13484709|title=Cradle of capitalism|publisher=|via=The Economist}}</ref> | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| Thus for much of history, capital and commercial trade existed, but it did not lead to industrialisation or dominate the production process of society. That required a set of conditions, including specific technologies of mass production, the ability to independently and privately own and trade in means of production, a class of workers willing to sell their ] for a living, a ] framework promoting commerce, a physical infrastructure allowing the circulation of goods on a large scale, and security for private accumulation. Many of these conditions do not currently exist in many ] countries, although there is plenty of capital and labour. Thus, the obstacles for the development of capitalist markets are less technical and more social, cultural and political. | |||

| The term "capitalist", meaning an owner of ], appears earlier than the term "capitalism" and dates to the mid-17th century. "Capitalism" is derived from ''capital'', which evolved from {{lang|la|capitale}}, a late ] word based on {{lang|la|caput}}, meaning "head"—which is also the origin of "]" and "]" in the sense of movable property (only much later to refer only to livestock). {{lang|la|Capitale}} emerged in the 12th to 13th centuries to refer to funds, stock of merchandise, sum of money or money carrying interest.<ref name="Braudel-1979">{{cite book |last=Braudel |first=Fernand |author-link=Fernand Braudel |title=The Wheels of Commerce: Civilization and Capitalism 15th–18th Century |publisher=] |date=1979}}</ref>{{rp|232}}<ref name="OED-93">]. "Capital". . ''Oxford English Press''. {{abbr|Vol.|Volume}} 2. p. 93.</ref> By 1283, it was used in the sense of the capital assets of a trading firm and was often interchanged with other words—wealth, money, funds, goods, assets, property and so on.<ref name="Braudel-1979" />{{rp|233}} | |||

| === Agrarian capitalism === | |||

| The economic foundations of the feudal agricultural system began to shift substantially in 16th-century England; the ] had broken down, and land began to become concentrated in the hands of fewer landlords with increasingly large estates. Instead of a ]-based system of labor, workers were increasingly employed as part of a broader and expanding money-based economy. The system put pressure on both landlords and tenants to increase the productivity of agriculture to make profit; the weakened coercive power of the ] to extract peasant ] encouraged them to try better methods, and the tenants also had incentive to improve their methods, in order to flourish in a competitive ]. Terms of rent for land were becoming subject to economic market forces rather than to the previous stagnant system of custom and feudal obligation.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Brenner|first1=Robert|title=The Agrarian Roots of European Capitalism|journal=Past & Present|date=1 January 1982|issue=97|pages=16–113|jstor=650630}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url= http://monthlyreview.org/1998/07/01/the-agrarian-origins-of-capitalism|title= The Agrarian Origins of Capitalism|accessdate= 17 December 2012}}</ref> | |||

| The ''Hollantse ({{langx|de|holländische}}) Mercurius'' uses "capitalists" in 1633 and 1654 to refer to owners of capital.<ref name="Braudel-1979" />{{rp|234}} In French, ] referred to ''capitalistes'' in 1788,<ref>E.g., "L'Angleterre a-t-elle l'heureux privilège de n'avoir ni Agioteurs, ni Banquiers, ni Faiseurs de services, ni Capitalistes ?" in (1788) ''De la foi publique envers les créanciers de l'état : lettres à M. Linguet sur le n° CXVI de ses annales'' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150319071130/http://books.google.com/books?id=ESMVAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA19 |date=19 March 2015 }}</ref> four years before its first recorded English usage by ] in his work ''Travels in France'' (1792).<ref name="OED-93" /><ref>Arthur Young. .</ref> In his '']'' (1817), ] referred to "the capitalist" many times.<ref>Ricardo, David. Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. 1821. John Murray Publisher, 3rd edition.</ref> English poet ] used "capitalist" in his work ''Table Talk'' (1823).<ref>Samuel Taylor Coleridge. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200223123202/https://books.google.com/books?id=ma-4W-XiGkIC |date=23 February 2020 }}. p. 267.</ref> ] used the term in his first work, '']'' (1840), to refer to the owners of capital. ] used the term in his 1845 work '']''.<ref name="OED-93" /> ] used "capitalist" in his ] presented to the United States Congress in 1791. | |||

| By the early 17th-century, England was a centralized state in which much of the feudal order of ] had been swept away. This centralization was strengthened by a good system of roads and by a disproportionately large capital city, ]. The capital acted as a central market hub for the entire country, creating a very large internal market for goods, contrasting with the fragmented feudal holdings that prevailed in most parts of the ]. | |||

| The initial use of the term "capitalism" in its modern sense is attributed to ] in 1850 ("What I call 'capitalism' that is to say the appropriation of capital by some to the exclusion of others") and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in 1861 ("Economic and social regime in which capital, the source of income, does not generally belong to those who make it work through their labor").<ref name="Braudel-1979" />{{rp|237}} ] frequently referred to the "]" and to the "capitalist mode of production" in '']'' (1867).<ref>{{cite book |last=Saunders |first=Peter |date=1995 |title=Capitalism |publisher=] |page=1}}</ref><ref name=":0">MEW, 23, & Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Oekonomie. Erster Band-Verlag von Otto Meissner (1867)</ref> Marx did not use the form ''capitalism'' but instead used ], ''capitalist'' and ''capitalist mode of production'', which appear frequently.<ref name=":0" /><ref>The use of the word "capitalism" appears in ''Theories of Surplus Value'', volume II. ToSV was edited by Kautsky.</ref> Due to the word being coined by socialist critics of capitalism, economist and historian ] stated that the term "capitalism" itself is a term of disparagement and a misnomer for ].<ref>Hessen, Robert (2008) "Capitalism", in Henderson, David R. (ed.) ''The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics'' p. 57</ref> ] agrees with the statement that the term is a misnomer, adding that it misleadingly suggests that there is such a thing as "]" that inherently functions in certain ways and is governed by stable economic laws of its own.<ref>Harcourt, Bernard E. (2020) ''For Coöperation and the Abolition of Capital, Or, How to Get Beyond Our Extractive Punitive Society and Achieve a Just Society'', Rochester, NY: Columbia Public Law Research Paper No. 14-672, p. 31</ref> | |||

| === Mercantilism === | |||

| {{Main article|Mercantilism}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The economic doctrine prevailing from the 16th to the 18th centuries is commonly called ].<ref name=GSGB /><ref name="Burnham">{{cite book |author=Burnham, Peter|title=Capitalism: The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2003}}</ref> This period, the ], was associated with the geographic exploration of the foreign lands by merchant traders, especially from England and the ]. Mercantilism was a system of trade for profit, although commodities were still largely produced by non-capitalist methods.<ref name="Scott" /> Most scholars consider the era of merchant capitalism and mercantilism as the origin of modern capitalism,<ref name="Burnham 2003">Burnham (2003)</ref><ref name="Encyclopædia Britannica 2006">''Encyclopædia Britannica'' (2006)</ref> although ] argued that the hallmark of capitalism is the establishment of generalized markets for what he called the "fictitious commodities:" land, labor, and money. Accordingly, he argued that "not until 1834 was a competitive labor market established in England, hence industrial capitalism as a social system cannot be said to have existed before that date.''<ref>Polanyi, Karl. ''The Great Transformation.'' Beacon Press, Boston. 1944. p. 87.</ref> | |||

| In the ], the term "capitalism" first appears, according to the '']'' (OED), in 1854, in the novel '']'' by novelist ], where the word meant "having ownership of capital".<ref name="OED-94">]. "Capitalism" p. 94.</ref> Also according to the OED, ], a ] ] and ], used the term "private capitalism" in 1863. | |||

| ] after the ], which began ] rule in India]] | |||

| England began a large-scale and integrative approach to mercantilism during the ] (1558–1603). A systematic and coherent explanation of balance of trade was made public through ]'s argument ''England's Treasure by Forraign Trade, or the Balance of our Forraign Trade is The Rule of Our Treasure.'' It was written in the 1620s and published in 1664.<ref>{{cite book |author1=David Onnekink|author2=Gijs Rommelse|title=Ideology and Foreign Policy in Early Modern Europe (1650–1750)|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M1QdbzdTimsC&pg=PA257|year= 2011|publisher=Ashgate Publishing|page=257|isbn=9781409419143}}</ref> | |||

| Other terms sometimes used for capitalism are: | |||

| European ]s, backed by state controls, subsidies, and ], made most of their profits by buying and selling goods. In the words of ], the purpose of mercantilism was "the opening and well-balancing of trade; the cherishing of manufacturers; the banishing of idleness; the repressing of waste and excess by sumptuary laws; the improvement and husbanding of the soil; the regulation of prices ..."<ref>Quoted in Sir George Clark, ''The Seventeenth Century'' (New York, Oxford University Press, 1961), p. 24.</ref> | |||

| * ]<ref>{{cite book |last=Mandel |first=Ernst |author-link=Ernst Mandel |title=An Introduction to Marxist Economic Theory |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Pf9Jd1sIMJ0C&pg=PA24 |year=2002 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-876646-30-1 |page=24 |access-date=29 January 2017 |archive-date=15 February 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170215160137/https://books.google.com/books?id=Pf9Jd1sIMJ0C&pg=PA24 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| * ]<ref>{{cite journal |title=Adam Smith and His Legacy for Modern Capitalism |last=Werhane |first=P. H. |journal=The Review of Metaphysics |volume=47 |year=1994 |issue=3}}</ref> | |||

| * Free enterprise<ref name="rogetfreeenterprise">{{cite encyclopedia |title=Free enterprise |encyclopedia=Roget's 21st Century Thesaurus |edition=Third |publisher=Philip Lief Group |date=2008}}</ref>{{page needed|date=July 2021}} | |||

| * Free enterprise economy<ref name="britannica" /> | |||

| * ]<ref name="rogetfreeenterprise" />{{page needed|date=July 2021}} | |||

| * Free market economy<ref name="britannica" /> | |||

| * '']''<ref name=Barrons>{{cite book |title=Barrons Dictionary of Finance and Investment Terms |date=1995 |page=74}}</ref> | |||

| * ]<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/market%20economy |title=Market economy |dictionary=Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary}}</ref> | |||

| * Profits system<ref>{{cite book |last=Shutt |first=Harry |title=Beyond the Profits System: Possibilities for the Post-Capitalist Era |publisher=] |year=2010 |isbn=978-1-84813-417-1}}</ref>{{page needed|date=July 2021}} | |||

| * Self-regulating market<ref name="rogetfreeenterprise" />{{page needed|date=July 2021}} | |||

| == Definition == | |||

| The ] and the ] inaugurated an expansive era of commerce and trade.<ref name=Banaji>{{cite journal |author=Banaji, Jairus|year=2007|title=Islam, the Mediterranean and the rise of capitalism|journal=Journal Historical Materialism|volume=15|pages=47–74|publisher=Brill Publishers|doi=10.1163/156920607X171591}}</ref><ref name="britannica2">{{cite book |title=Economic system:: Market systems|url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/178493/economic-system/61117/Market-systems#toc242146|publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica|year=2006}}</ref> These companies were characterized by their ] and ] powers given to them by nation-states.<ref name="Banaji" /> During this era, merchants, who had traded under the previous stage of mercantilism, invested capital in the East India Companies and other colonies, seeking a ]. | |||

| There is no universally agreed upon definition of capitalism; it is unclear whether or not capitalism characterizes an entire society, a specific type of social order, or crucial | |||

| components or elements of a society.<ref name="wolf">{{cite encyclopedia |last=Wolf |first=Harald |editor1-last=Ritzer |editor1-first=George|title=Capitalism |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of Social Theory|pages=76–80|date=2004 |publisher=Sage Publications|isbn=978-1-4522-6546-9}}</ref> Societies officially founded in opposition to capitalism (such as the ]) have sometimes been argued to actually exhibit characteristics of capitalism.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Howard |first1=M.C. |last2=King |first2=J.E. |title='State Capitalism' in the Soviet Union |journal=History of Economics Review |date=January 2001 |volume=34 |issue=1 |pages=110–126 |doi=10.1080/10370196.2001.11733360 |s2cid=42809979 |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10370196.2001.11733360 |language=en |issn=1037-0196}}</ref> ] describes usage of the term "capitalism" by many authors as "mainly rhetorical, functioning less as an actual concept than as a gesture toward the | |||

| need for a concept".<ref name="harris"/> Scholars who are uncritical of capitalism rarely actually use the term "capitalism".<ref name="delacroix">{{cite encyclopedia |last=Delacroix |first=Jacques |editor1-last=Ritzer |editor1-first=George |title=Capitalism |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of Social Theory|date=2007 |publisher=Wiley|doi=10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosc004 |isbn=978-1-4051-2433-1|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosc004}}</ref> | |||

| Some doubt that the term "capitalism" possesses valid scientific dignity,<ref name="wolf"/> and it is generally not discussed in ],<ref name="harris"/> with economist ] suggesting that the term "capitalism" should be abandoned entirely.<ref>{{cite book |last=Acemoglu |first=Daron |date=2017 |editor1-last=Frey |editor1-first=Bruno S.|editor2-last = Iselin|editor2-first = David |title=Economic Ideas You Should Forget |publisher=Springer|pages=1–3 |chapter=Capitalism|doi=10.1007/978-3-319-47458-8_1 |isbn=978-3-319-47457-1|chapter-url=https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-47458-8_1}}</ref> Consequently, understanding of the concept of capitalism tends to be heavily influenced by opponents of capitalism and by the followers and critics of Karl Marx.<ref name="delacroix"/> | |||

| == History == | |||

| {{Main|History of capitalism}} | |||

| ]: the ] fuelled primarily by ] propelled the ] in ]<ref>Watt steam engine image: located in the lobby of into the Superior Technical School of Industrial Engineers of the UPM {{clarify|date=April 2016}} (])</ref>]] | |||

| ] (pictured in a 16th-century portrait by ]) built an international financial empire and was one of the first ]ers.]] | |||

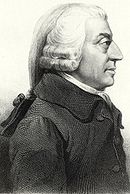

| In the mid-18th century, a new group of economic theorists, led by ]<ref>{{cite book |author=Hume, David|title=Political Discourses|location=Edinburgh|publisher=A. Kincaid & A. Donaldson|year=1752}}</ref> and ], challenged fundamental ] doctrines such as the belief that the world's wealth remained constant and that a state could only increase its wealth at the expense of another state. | |||

| ], the centre of early capitalism<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last1=Behringer |first1=Wolfgang |contribution=Core and Periphery: The Holy Roman Empire as a Communication(s) Universe |title=The Holy Roman Empire, 1495–1806 |date=2011 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-960297-1 |pages=347–358|url=https://perspectivia.net/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/pnet_derivate_00004689/behringer_core.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/https://perspectivia.net/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/pnet_derivate_00004689/behringer_core.pdf |archive-date=9 October 2022 |url-status=live |access-date=7 August 2022}}</ref>]] | |||

| Capitalism, in its modern form, can be traced to the emergence of agrarian capitalism and mercantilism in the early ], in city-states like ].<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.economist.com/node/13484709 |title=Cradle of capitalism |newspaper=] |date=16 April 2009 |access-date=9 March 2015 |archive-date=18 January 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180118055643/http://www.economist.com/node/13484709 |url-status=live}}</ref> ] has existed incipiently on a small scale for centuries<ref name="WarburtonDavid">{{cite book |last=Warburton |first=David |title=Macroeconomics from the beginning: The General Theory, Ancient Markets, and the Rate of Interest |location=Paris |publisher=Recherches et Publications |date=2003 |pages=49}}</ref> in the form of merchant, renting and lending activities and occasionally as small-scale industry with some wage labor. Simple ] exchange and consequently simple commodity production, which is the initial basis for the growth of capital from trade, have a very long history. During the ], ] promulgated capitalist economic policies such as free trade and banking. Their use of ] facilitated ]. These innovations migrated to Europe through trade partners in cities such as Venice and Pisa. Italian ] traveled the Mediterranean talking to Arab traders and returned to popularize the use of Indo-Arabic numerals in Europe.<ref name="Koehler, Benedikt">{{cite book |last=Koehler |first=Benedikt |title=Early Islam and the Birth of Capitalism |quote=In Baghdad, by the early tenth century a fully-fledged banking sector had come into being... |pages=2 |publisher=] |date=2014}}</ref> | |||

| During the ], industrialists replaced merchants as a dominant factor in the capitalist system and affected the decline of the traditional handicraft skills of ]s, guilds, and ]. Also during this period, the surplus generated by the rise of commercial agriculture encouraged increased mechanization of agriculture. Industrial capitalism marked the development of the ] system of manufacturing, characterized by a complex ] between and within work process and the routine of work tasks; and finally established the global domination of the capitalist mode of production.<ref name="Burnham"/> | |||

| === Agrarianism === | |||

| Britain also abandoned its ] policy, as embraced by mercantilism. In the 19th century, ] and ], who based their beliefs on the ], initiated a movement to lower tariffs.<ref name="laissezf">{{cite web|title=laissez-faire |url=http://www.bartleby.com/65/la/laissezf.html |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20081202050426/http://www.bartleby.com/65/la/laissezf.html |archivedate=2 December 2008 |df=dmy }}</ref> In the 1840s, Britain adopted a less protectionist policy, with the repeal of the ] and the ].<ref name="Burnham"/> Britain reduced ] and ], in line with David Ricardo's advocacy for ]. | |||

| The economic foundations of the feudal agricultural system began to shift substantially in 16th-century England as the ] had broken down and land began to become concentrated in the hands of fewer landlords with increasingly large estates. Instead of a ]-based system of labor, workers were increasingly employed as part of a broader and expanding money-based economy. The system put pressure on both landlords and tenants to increase the productivity of agriculture to make profit; the weakened coercive power of the ] to extract peasant ] encouraged them to try better methods, and the tenants also had incentive to improve their methods in order to flourish in a competitive ]. Terms of rent for land were becoming subject to economic market forces rather than to the previous stagnant system of custom and feudal obligation.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Brenner |first1=Robert |title=The Agrarian Roots of European Capitalism |journal=] |date=1 January 1982 |issue=97 |pages=16–113 |doi=10.1093/past/97.1.16 |jstor=650630}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://monthlyreview.org/1998/07/01/the-agrarian-origins-of-capitalism |title=The Agrarian Origins of Capitalism |access-date=17 December 2012 |date=July 1998 |archive-date=11 December 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191211183143/https://monthlyreview.org/1998/07/01/the-agrarian-origins-of-capitalism/ |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| === |

=== Mercantilism === | ||

| {{Main|Mercantilism}} | |||

| {{Expand section|date=February 2017}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] formed the financial basis of the international economy from 1870–1914]] | |||

| ] with the ] after the ] which began the British rule in ]]] | |||

| Capitalism was carried across the world by broader processes of ] and, by the end of the 18th century, became the dominant ''global'' economic system, in turn intensifying processes of economic and other globalization.<ref>{{Cite book | year= 2007 | last1= James | first1= Paul | authorlink= Paul James (academic) | last2= Gills | first2= Barry | title= Globalization and Economy, Vol. 1: Global Markets and Capitalism | url= http://www.academia.edu/4199690/Globalization_and_Economy_Vol._1_Global_Markets_and_Capitalism_editor_with_Barry_Gills_Sage_Publications_London_2007 | publisher= Sage Publications | location= London}}</ref> Later, in the 20th century, capitalism overcame a challenge by ] and is now the encompassing system worldwide,<ref name="britannica">{{cite book |title=Capitalism|publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica|url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/93927/capitalism|date=10 November 2014}}</ref><ref>James Fulcher, ''Capitalism, A Very Short Introduction''. “In one respect there can, however, be little doubt that capitalism has gone global and that is in the elimination of alternative systems.” p. 99. Oxford University Press, 2004. {{ISBN|978-0-19-280218-7}}.</ref> with the ] being its dominant form in the industrialized Western world. | |||

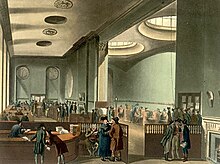

| The economic doctrine prevailing from the 16th to the 18th centuries is commonly called ].<ref name=GSGB>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Pf9Jd1sIMJ0C |title=An Introduction to Marxist Economic Theory |date= 2002 |publisher=] |via=] |isbn=978-1-876646-30-1 |access-date=27 August 2016 |archive-date=11 December 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161211173733/https://books.google.com/books?id=Pf9Jd1sIMJ0C |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Burnham">{{cite book |last=Burnham |first=Peter |author-link=Peter Burnham |title=Capitalism: The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics |publisher=] |year=2003}}</ref> This period, the ], was associated with the geographic exploration of foreign lands by merchant traders, especially from England and the ]. Mercantilism was a system of trade for profit, although commodities were still largely produced by non-capitalist methods.<ref name="Scott" /> Most scholars consider the era of merchant capitalism and mercantilism as the origin of modern capitalism,<ref name="Burnham"/><ref name="Encyclopædia Britannica 2006">''Encyclopædia Britannica'' (2006)</ref> although ] argued that the hallmark of capitalism is the establishment of generalized markets for what he called the "fictitious commodities", i.e. land, labor and money. Accordingly, he argued that "not until 1834 was a competitive labor market established in England, hence industrial capitalism as a social system cannot be said to have existed before that date".<ref>{{cite book |last=Polanyi |first=Karl |author-link=Karl Polanyi |title=The Great Transformation |publisher=] |location=Boston |date=1944 |pages=87}}</ref> | |||

| England began a large-scale and integrative approach to mercantilism during the ] (1558–1603). A systematic and coherent explanation of balance of trade was made public through ]'s argument ''England's Treasure by Forraign Trade, or the Balance of our Forraign Trade is The Rule of Our Treasure.'' It was written in the 1620s and published in 1664.<ref>{{cite book |first1=David |last1=Onnekink |first2=Gijs |last2=Rommelse |title=Ideology and Foreign Policy in Early Modern Europe (1650–1750) |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M1QdbzdTimsC&pg=PA257 |year=2011 |publisher=] |page=257 |isbn=978-1-4094-1914-3 |access-date=27 June 2015 |archive-date=19 March 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150319130220/http://books.google.com/books?id=M1QdbzdTimsC&pg=PA257 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ] allowed cheap production of household items using ], while rapid population growth created sustained demand for commodities. Globalization in this period was decisively shaped by 18th-century ].<ref>{{Cite book | year= 2007 | last1= James | first1= Paul | authorlink= Paul James (academic) | last2= Gills | first2= Barry | title= Globalization and Economy, Vol. 1: Global Markets and Capitalism | url= https://www.academia.edu/4199690/Globalization_and_Economy_Vol._1_Global_Markets_and_Capitalism_editor_with_Barry_Gills_Sage_Publications_London_2007 | publisher= Sage Publications | location= London}}</ref> | |||

| European ]s, backed by state controls, subsidies and ], made most of their profits by buying and selling goods. In the words of ], the purpose of mercantilism was "the opening and well-balancing of trade; the cherishing of manufacturers; the banishing of idleness; the repressing of waste and excess by sumptuary laws; the improvement and husbanding of the soil; the regulation of prices...".<ref>Quoted in {{cite book |first=George |last=Clark |title=The Seventeenth Century |location=New York |publisher=] |date=1961 |page=24}}</ref> | |||

| After the ] and ]s and the completion of British conquest of India, vast populations of these regions became ready consumers of European exports. Also in this period, areas of sub-Saharan Africa and the Pacific islands were incorporated into the world system. Meanwhile, the conquest of new parts of the globe, notably sub-Saharan Africa, by Europeans yielded valuable natural resources such as ], ] and ] and helped fuel trade and investment between the European imperial powers, their colonies, and the United States. | |||

| After the period of the ], the ] and the ], after massive contributions from the ],<ref name="Prakash">], "", ''History of World Trade Since 1450'', edited by ], vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 237–240, ''World History in Context''. Retrieved 3 August 2017</ref><ref name="ray">{{cite book |first=Indrajit |last=Ray |year=2011 |title=Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857) |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CHOrAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA57 |publisher=] |pages=57, 90, 174 |isbn=978-1-136-82552-1 |access-date=20 June 2019 |archive-date=29 May 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160529021839/https://books.google.com/books?id=CHOrAgAAQBAJ |url-status=live}}</ref> inaugurated an expansive era of commerce and trade.<ref name=Banaji>{{cite journal |last=Banaji |first=Jairus |year=2007 |title=Islam, the Mediterranean and the rise of capitalism |journal=] |volume=15 |pages=47–74 |doi=10.1163/156920607X171591 |url=http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/15983/1/Islam%20and%20capitalism.pdf |access-date=20 April 2018 |archive-date=29 March 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180329015002/http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/15983/1/Islam%20and%20capitalism.pdf |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="britannica2">{{cite book |title=Economic system:: Market systems |url=https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/178493/economic-system/61117/Market-systems#toc242146 |publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica |year=2006 |access-date=4 January 2009 |archive-date=24 May 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090524075921/https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/178493/economic-system/61117/Market-systems#toc242146 |url-status=live}}</ref> These companies were characterized by their ] and ] powers given to them by nation-states.<ref name="Banaji" /> During this era, merchants, who had traded under the previous stage of mercantilism, invested capital in the East India Companies and other colonies, seeking a ]. | |||

| <blockquote>The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea, the various products of the whole earth, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep. Militarism and imperialism of racial and cultural rivalries were little more than the amusements of his daily newspaper. What an extraordinary episode in the economic progress of man was that age which came to an end in August 1914.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/shared/minitext/tr_show01.html |title=PBS.org |publisher=PBS.org |date=24 October 1929 |accessdate=31 July 2010}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| === Industrial Revolution === | |||

| In this period, the global financial system was mainly tied to the ]. The ] first formally adopted this standard in 1821. Soon to follow were ] in 1853, ] in 1865, the ] and Germany ('']'') in 1873. New technologies, such as the ], the ], the ], the ] and ] allowed goods and information to move around the world at an unprecedented degree.<ref>Michael D. Bordo, Barry Eichengreen, Douglas A. Irwin. ''Is Globalization Today Really Different than Globalization a Hundred Years Ago?'' NBER {{clarify|date=April 2016}} Working Paper No. 7195. June 1999.</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Industrial Revolution}} | |||

| ], fuelled primarily by ], propelled the ] in ].<ref>Watt steam engine image located in the lobby of the Superior Technical School of Industrial Engineers of the ]{{clarify|date=April 2016}} (]).</ref>]] | |||

| In the mid-18th century a group of economic theorists, led by ] (1711–1776)<ref>{{cite book |last=Hume |first=David |author-link=David Hume |title=Political Discourses |url=https://archive.org/details/McGillLibrary-125702-2590 |location=Edinburgh |publisher=A. Kincaid & A. Donaldson |year=1752}}</ref> and ] (1723–1790), challenged fundamental mercantilist doctrines—such as the belief that the world's wealth remained constant and that a state could only increase its wealth at the expense of another state. | |||

| During the ], ] replaced merchants as a dominant factor in the capitalist system and effected the decline of the traditional handicraft skills of ]s, guilds and ]. Industrial capitalism marked the development of the ] of manufacturing, characterized by a complex ] between and within work process and the routine of work tasks; and eventually established the domination of the ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Burnham |first1=Peter |author1-link=Peter Burnham |year=1996 |chapter=Capitalism |editor1-last=McLean |editor1-first=Iain |editor2-last=McMillan |editor2-first=Alistair |title=The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8JkyAwAAQBAJ |series=Oxford Quick Reference |edition=3 |location=Oxford |publisher=] |publication-date=2009 |isbn=978-0-19-101827-5 |access-date=14 September 2019 |quote=Industrial capitalism, which Marx dates from the last third of the eighteenth century, finally establishes the domination of the capitalist mode of production. |archive-date=27 July 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200727163404/https://books.google.com/books?id=8JkyAwAAQBAJ |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ] ] (1963)]] | |||

| In the period following the global depression of the 1930s, the state played an increasingly prominent role in the capitalistic system throughout much of the world. The postwar boom ended in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and the situation was worsened by the rise of ].<ref>{{cite book |author=Barnes, Trevor J.|title=Reading economic geography|publisher=Blackwell Publishing|isbn=0-631-23554-X|page=127|year=2004}}</ref> ], a modification of Keynesianism that is more compatible with laissez-faire, gained increasing prominence in the capitalist world, especially under the leadership of ] in the U.S. and ] in the UK in the 1980s. Public and political interest began shifting away from the so-called ] concerns of Keynes's managed capitalism to a focus on individual choice, called "remarketized capitalism".<ref name="Fulcher, James 2004">Fulcher, James. ''Capitalism''. 1st {{abbr|ed.|edition}} New York, Oxford University Press, 2004.</ref> | |||

| Industrial Britain eventually abandoned the ] policy formerly prescribed by mercantilism. In the 19th century, ] (1804–1865) and ] (1811–1889), who based their beliefs on the ], initiated a movement to lower ].<ref name="laissezf">{{cite web |title=Laissez-faire |url=http://www.bartleby.com/65/la/laissezf.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081202050426/http://www.bartleby.com/65/la/laissezf.html |archive-date=2 December 2008}}</ref> In the 1840s Britain adopted a less protectionist policy, with the 1846 repeal of the ] and the 1849 repeal of the ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Burnham |first1=Peter |author1-link=Peter Burnham |year=1996 |chapter=Capitalism |editor1-last=McLean |editor1-first=Iain |editor2-last=McMillan |editor2-first=Alistair |title=The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8JkyAwAAQBAJ |series=Oxford Quick Reference |edition=3 |location=Oxford |publisher=] |publication-date=2009 |isbn=978-0-19-101827-5 |access-date=14 September 2019 |quote=For most analysts, mid- to late-nineteenth century Britain is seen as the apotheosis of the laissez-faire phase of capitalism. This phase took off in Britain in the 1840s with the repeal of the Corn Laws, and the Navigation Acts, and the passing of the Banking Act. |archive-date=27 July 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200727163404/https://books.google.com/books?id=8JkyAwAAQBAJ |url-status=live}}</ref> Britain reduced tariffs and ], in line with David Ricardo's advocacy of ]. | |||

| According to Harvard academic ] a new genus of capitalism, ] monetizes data acquired through ].<ref>{{cite web|last1=Powles|first1=Julia|title=Google and Microsoft have made a pact to protect surveillance capitalism|url=https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/may/02/google-microsoft-pact-antitrust-surveillance-capitalism|publisher=The Guardian|accessdate=9 February 2017|date=2 May 2016}}</ref><ref name=faz1>{{cite web|last1=Zuboff|first1=Shoshana|title=Google as a Fortune Teller: The Secrets of Surveillance Capitalism|url=http://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/debatten/the-digital-debate/shoshana-zuboff-secrets-of-surveillance-capitalism-14103616.html?printPagedArticle=true|publisher=Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung|accessdate=9 February 2017|date=5 March 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last1=Sterling|first1=Bruce|title=Shoshanna Zuboff condemning Google "surveillance capitalism"|url=https://www.wired.com/beyond-the-beyond/2016/03/shoshanna-zuboff-condemning-google-surveillance-capitalism/|publisher=WIRED|accessdate=9 February 2017}}</ref> She states it was first discovered and consolidated at ], emerged due to the "coupling of the vast powers of the ] with the radical indifference and intrinsic narcissism of the ] and its ] vision that have dominated commerce for at least three decades, especially in the Anglo economies"<ref name=faz1/> and depends on the global architecture of computer mediation which produces a distributed and largely uncontested new expression of power she calls "Big Other".<ref name=ssrn>{{cite journal|last1=Zuboff|first1=Shoshana|title=Big other: surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization|journal=Journal of Information Technology|date=9 April 2015|volume=30|issue=1|pages=75–89|doi=10.1057/jit.2015.5|ssrn=2594754|accessdate=|publisher=Social Science Research Network}}</ref> | |||

| === Modernity === | |||

| ] |

] formed the financial basis of the international economy from 1870 to 1914.]] | ||

| The relationship between ] and capitalism is a contentious area in theory and in popular political movements. The extension of universal adult male ] in 19th century Britain occurred along with the development of industrial capitalism, and democracy became widespread at the same time as capitalism, leading capitalists to posit a causal or mutual relationship between them.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Kaminski|first1=Joseph|title=Capitalism and the Industrial Revolution|url=http://josephkaminski.net/2013/10/30/capitalism-and-industrial-revolution/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150128024314/http://josephkaminski.net/2013/10/30/capitalism-and-industrial-revolution/|dead-url=yes|archive-date=28 January 2015}}</ref> However, in the 20th century, according to some authors, capitalism also accompanied a variety of political formations quite distinct from liberal democracies, including ] regimes, absolute monarchies, and single-party states.<ref name="Burnham" /> Democratic peace theory asserts that democracies seldom fight other democracies, but critics of that theory suggest that this may be because of political similarity or stability rather than because they are democratic or capitalist. | |||

| Broader processes of ] carried capitalism across the world. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, a series of loosely connected market systems had come together as a relatively integrated global system, in turn intensifying processes of economic and other globalization.<ref name="SAGE Publications">{{cite book |year=2007 |last1=James |first1=Paul |author-link=Paul James (academic) |last2=Gills |first2=Barry |title=Globalization and Economy, Vol. 1: Global Markets and Capitalism |url=https://www.academia.edu/4199690 |publisher=] |location=London |page=xxxiii}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=Impact of Global Capitalism on the Environment of Developing Economies |url=http://s-space.snu.ac.kr/bitstream/10371/93716/1/04_Osariyekemwen%20Igiebor.pdf |journal=Impact of Global Capitalism on the Environment of Developing Economies: The Case of Nigeria |pages=84 |access-date=31 July 2020 |archive-date=20 March 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200320071239/http://s-space.snu.ac.kr/bitstream/10371/93716/1/04_Osariyekemwen%20Igiebor.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> Late in the 20th century, capitalism overcame a challenge by ] and is now the encompassing system worldwide,<ref name="britannica">{{cite book |title=Capitalism |publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/93927/capitalism |date=10 November 2014 |access-date=24 March 2015 |archive-date=29 June 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110629021539/https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/93927/capitalism |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=James |first=Fulcher |title=Capitalism, A Very Short Introduction |quote=In one respect there can, however, be little doubt that capitalism has gone global and that is in the elimination of alternative systems |pages=99 |publisher=] |date=2004 |isbn=978-0-19-280218-7}}</ref> with the ] as its dominant form in the industrialized Western world. | |||

| Moderate critics argue that though economic growth under capitalism has led to democracy in the past, it may not do so in the future, as ] regimes have been able to manage economic growth without making concessions to greater political freedom.<ref>{{cite web|author=Mesquita, Bruce Bueno de |url=http://www.foreignaffairs.org/20050901faessay84507/bruce-bueno-de-mesquita-george-w-downs/development-and-democracy.html |title=Development and Democracy |date=September 2005 |accessdate=26 February 2008 |work=Foreign Affairs |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080220154505/http://www.foreignaffairs.org/20050901faessay84507/bruce-bueno-de-mesquita-george-w-downs/development-and-democracy.html |archivedate=20 February 2008 |df= }}</ref><ref>{{cite news|author=Single, Joseph T. |url=http://www10.nytimes.com/cfr/international/20040901facomment_v83n4_siegle-weinstein-halperin.html?_r=5&oref=slogin&oref=slogin&oref=slogin&oref=slogin |title=Why Democracies Excel |date=September 2004 |accessdate=26 February 2008 |work=The New York Times }}{{dead link|date=June 2017 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> | |||

| ] allowed cheap production of household items using ], while rapid ] created sustained demand for commodities. The ] of the 18th-century decisively shaped globalization.<ref name="SAGE Publications" /><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Thomas |first1=Martin |last2=Thompson |first2=Andrew |date=1 January 2014 |title=Empire and Globalisation: from 'High Imperialism' to Decolonisation |journal=The International History Review |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=142–170 |doi=10.1080/07075332.2013.828643 |s2cid=153987517 |issn=0707-5332|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=Globalization and Empire |url=https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/47230635.pdf |journal=Globalization and Empire |access-date=31 July 2020 |archive-date=23 September 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200923063531/https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/47230635.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=Europe and the causes of globalization |url=https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/7045619.pdf |journal=Europe and the Causes of Globalization, 1790 to 2000 |access-date=31 July 2020 |archive-date=7 December 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171207091124/https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/7045619.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| One of the biggest supporters of the idea that capitalism promotes political freedom, Milton Friedman, argues that competitive capitalism allows economic and political power to be separate, ensuring that they do not clash with one another. This idea has been challenged given the current influence capitalist lobbying has had on policy in the United States. The approval of ], has led people to question the very idea that competitive capitalism promotes political freedom. The ruling on Citizens United allows corporations to spend undisclosed and unregulated amounts of money on political campaigns, shifting outcomes to the interests and undermining true democracy. As explained in Robin Hahnel’s writings, the centerpiece of the ideological defense of the free market system is the concept of economic freedom, and that supporters equate economic democracy with economic freedom and claim that only the free market system can provide economic freedom. According to Hahnel, there are a few objections to the premise that capitalism offers freedom through economic freedom. These objections are guided by critical questions about who or what decides whose freedoms are more protected. Often, the question of inequality is brought up when discussing how well capitalism promotes democracy. An argument that could stand is that economic growth can lead to inequality given that capital can be acquired at different rates by different people. In '']'', ] of the ] asserts that inequality is the inevitable consequence of economic growth in a capitalist economy and the resulting ] can destabilize democratic societies and undermine the ideals of social justice upon which they are built.<ref>] (2014). ''Capital in the Twenty-First Century.'' ]. {{ISBN|0-674-43000-X}} p. 571.</ref> ], ] (except for ]), and other leftists argue that capitalism is incompatible with democracy since capitalism according to Marx entails "dictatorship of the ]" (owners of the means of production) while democracy entails rule by the people. | |||

| After the ] and ]s (1839–60) by ] and ] and the completion of the ] conquest of India by 1858 and the ] conquest of ], ] and ] by 1887, vast populations of Asia became consumers of European exports. Europeans colonized areas of Africa and the Pacific islands. Colonisation by Europeans, notably of Africa by the British and French, yielded valuable natural resources such as ], ] and ] and helped fuel trade and investment between the European imperial powers, their colonies and the United States: | |||

| States with capitalistic economic systems have thrived under political regimes deemed to be authoritarian or oppressive. Singapore has a successful open market economy as a result of its competitive, business-friendly climate and robust rule of law; nonetheless, it often comes under fire for (1) its brand of government, which, though democratic and consistently one of the least corrupt,<ref>{{cite web|title=Transparency International Corruption Measure 2015|url=https://www.transparency.org/country/#SGP|website=Transparency International Corruption Measure 2015 – By Country / Territory|publisher=Transparency International|accessdate=20 September 2016}}</ref> operates largely under a one-party rule, and (2) not vigorously defending freedom of expression, given its government-regulated press, as well as penchant for upholding laws protecting ethnic and religious harmony, judicial dignity and personal reputation. The private (capitalist) sector in the People's Republic of China has grown exponentially and thrived since its inception, despite having an authoritarian government. ]'s rule in Chile led to economic growth and high levels of inequality<ref>] (2008). ''].'' ]. {{ISBN|0-312-42799-9}} .</ref> by using authoritarian means to create a safe environment for investment and capitalism. | |||

| {{blockquote|The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea, the various products of the whole earth, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep. Militarism and imperialism of racial and cultural rivalries were little more than the amusements of his daily newspaper. What an extraordinary episode in the economic progress of man was that age which came to an end in August 1914.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/shared/minitext/tr_show01.html |title=Commanding Heights: Episode One: The Battle of Ideas |publisher=] |date=24 October 1929 |access-date=31 July 2010 |archive-date=30 March 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100330093746/http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/shared/minitext/tr_show01.html |url-status=live}}</ref>}} | |||

| === Varieties of capitalism === | |||

| Peter A. Hall and ] argued that modern economies have developed two different forms of capitalism: liberal market economies (or LME) (e.g. US, UK, Canada, New Zealand, Ireland) and coordinated market economies (CME) (e.g. Germany, Japan, Sweden, Austria). Those two types can be distinguished by the primary way in which firms coordinate with each other and other actors, such as ]. In LMEs firms primarily coordinate their endeavors by way of hierarchies and market mechanisms. Coordinated market economies more heavily rely on non-market forms of interaction in the coordination of their relationship with other actors (for a detailed description see '']''). These two forms of capitalisms developed different ], ] and ], ], inter-firm relations and relations with employees. The existence of these different forms of capitalism has important societal effects, especially in periods of crisis and instability. Since the early 2000s the number of labor market outsiders has rapidly grown in Europe, especially among the youth, potentially influencing social and political participation. Using varieties of capitalism theory it is possible to disentangle the different effects on social and political participation that an increase of labor market outsiders has in liberal and coordinated market economies (Ferragina et al. 2016).<ref>Emanuele Ferragina et al.(2016). "Outsiderness and participation in liberal market economies." PACO ''The Open Journal of Sociopolitical Studies'', 9, 986–1014 http://scholar.google.fr/scholar_url?url=http%3A%2F%2Fsiba-ese.unisalento.it%2Findex.php%2Fpaco%2Farticle%2Fdownload%2F16664%2F14327&hl=fr&sa=T&ei=AN-iWPD-EIupmAHrx5vACw&scisig=AAGBfm3_dOCLibWFNHNtG62FKywcq7PxNA&nossl=1&ws=1920x909</ref> The social and political disaffection, especially among the youth, seems to be more pronounced in liberal than coordinated market economies. This signals an important problem for liberal market economies in a period of crisis. If the market does not provide consistent job opportunities (as it has in previous decades), the shortcomings of liberal social security systems may depress social and political participation even further than in other capitalist economies. | |||

| From the 1870s to the early 1920s, the global financial system was mainly tied to the ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Eichengreen|first=Barry|author-link=Barry Eichengreen|date=6 August 2019|title=Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System|edition=3rd|publisher=]|doi=10.2307/j.ctvd58rxg|isbn=978-0-691-19458-5|s2cid=240840930 |lccn=2019018286}}{{page needed|date=December 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Eichengreen|first1=Barry|author-link=Barry Eichengreen|last2=Esteves|first2=Rui Pedro|date=2021|editor1-last=Fukao|editor1-first=Kyoji|editor2-last=Broadberry|editor2-first=Stephen|editor2-link=Stephen Broadberry|section=International Finance|title=The Cambridge Economic History of the Modern World|publisher=]|volume=2: ''1870 to the Present''|pages=501–525|isbn=978-1-107-15948-8}}</ref> The United Kingdom first formally adopted this standard in 1821. Soon to follow were ] in 1853, ] in 1865, the United States and Germany ('']'') in 1873. New technologies, such as the ], the ], the ], the ] and ]s allowed goods and information to move around the world to an unprecedented degree.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.nber.org/papers/w7195 |last1=Bordo |first1=Michael D. |author1-link=Michael D. Bordo |last2=Eichengreen |first2=Barry |author2-link=Barry Eichengreen |last3=Irwin |first3=Douglas A. |title=Is Globalization Today Really Different than Globalization a Hundred Years Ago? |series=NBER |number=Working Paper No. 7195 |date=June 1999|doi=10.3386/w7195 }}</ref> | |||

| == Characteristics == | |||

| {{Further information|Academic perspectives on capitalism}}Capitalism is "production for exchange" driven by the desire for personal accumulation of money receipts in such exchanges, mediated by free markets. The markets themselves are driven by the needs and wants of consumers and those of society as a whole. Contemporary mainstream economics, particularly that associated with the ], holds that by an "]",<ref>Adam Smith, often mis-attributed in this sense. See the ] section for what Smith actually said.</ref> through little more than the freedom of the market, is able to match social production to these needs and desires.<ref name="xxx31"/> | |||

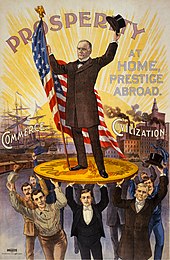

| In the United States, the term "capitalist" primarily referred to powerful businessmen<ref>{{Cite book |last=Andrews |first=Thomas G. |title=Killing for Coal: America's Deadliest Labor War |publisher=] |year=2008 |isbn=978-0-674-03101-2 |location=Cambridge |page=64 |author-link=Thomas G. Andrews (historian)}}</ref> until the 1920s due to widespread societal skepticism and criticism of capitalism and its most ardent supporters. | |||

| === Summary === | |||

| In general, capitalism as an economic system and mode of production can be summarised by the following:<ref>{{cite web|url=http://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft3n39n8x3&chunk.id=d0e1212&toc.id=&brand=ucpress|title=Althusser and the Renewal of Marxist Social Theory|publisher=}}</ref> | |||

| * ]:<ref name=ch32>{{cite web|url=https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch32.htm|title=Economic Manuscripts: Capital Vol. I – Chapter Thirty Two|first=Karl|last=Marx|publisher=}}</ref> Production for profit and accumulation as the implicit purpose of all or most of production, constriction or elimination of production formerly carried out on a common social or private household basis.<ref name=xxx31 /> | |||

| * ]: Production for exchange on a market; to maximise ] instead of ]. | |||

| * ] of the means of production:<ref name="Modern Economics 1986, p. 54"/> | |||

| * High levels of ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/lmac/self-employed-workers-in-the-uk/2014/rep-self-employed-workers-in-the-uk-2014.html#tab-Self-employed-workers-in-the-UK---2014|title= UK Government Web Archive – The National Archives|first=Internet Memory|last=Foundation|publisher=}}</ref> | |||

| * The ] of money to make a profit.<ref>James Fulcher, ''Capitalism A Very Short Introduction'', "the investment of money in order to make a profit, the essential feature of capitalism", p. 14, Oxford, 2004, {{ISBN|978-0-19-280218-7}}.</ref> | |||

| * The use of the ] to allocate resources between competing uses.<ref name="Modern Economics 1986, p. 54"/> | |||

| ] ] (1963)]] | |||

| === The market === | |||

| ] at each price (demand, D): this results in a market equilibrium, with a given quantity (Q) sold of the product, whereas a rise in demand would result in an increase in price and an increase in output]] | |||

| In free-market and '']'' forms of capitalism, markets are used most extensively with minimal or no regulation over the pricing mechanism. In mixed economies, which are almost universal today,<ref>James Fulcher, ''Capitalism A Very Short Introduction'', "...in the wake of the 1970 crisis, the neo-liberal model of capitalism became intellectually and ideologically dominant", p. 58, Oxford, 2004, {{ISBN|978-0-19-280218-7}}.</ref> markets continue to play a dominant role but are regulated to some extent by government in order to correct ]s, promote ], conserve ]s, fund ] and ] or for other reasons. In ] systems, markets are relied upon the least, with the state relying heavily on ] or indirect economic planning to accumulate capital. | |||

| Contemporary capitalist societies developed in the West from 1950 to the present and this type of system continues throughout the world—relevant examples started in the ], ], ], ], and others. At this stage most capitalist markets are considered{{by whom|date=July 2021}} developed and characterized by developed private and public markets for equity and debt, a high ] (as characterized by the ] and the ]), large institutional investors and a well-funded ]. A significant ] has emerged{{when|date=July 2021}} and decides on a significant proportion of investments and other decisions. A different future than that envisioned by Marx has started to emerge—explored and described by ] in the United Kingdom in his 1956 book '']''<ref>{{cite book |last=Crosland |first=Anthony |title=The Future of Socialism |publisher=Jonathan Cape |year=1956 |location=United Kingdom}}{{page needed|date=December 2023}}</ref> and by ] in North America in his 1958 book '']'',<ref>{{cite book |last=Galbraith |first=John Kenneth |title=The Affluent Society |publisher=] |year=1958 |location=United States}}{{page needed|date=December 2023}}</ref> 90 years after Marx's research on the state of capitalism in 1867.<ref>{{cite book |last=Shiller |first=Robert |title=Finance and The Good Society |publisher=] |year=2012 |location=United States}}{{page needed|date=December 2023}}</ref> | |||

| Supply is the amount of a good or service produced by a firm and which is available for sale. Demand is the amount that people are willing to buy at a specific price. Prices tend to rise when demand exceeds supply, and fall when supply exceeds demand. In theory, the market is able to coordinate itself when a new equilibrium price and quantity is reached. | |||

| The ] ended in the late 1960s and early 1970s and the economic situation grew worse with the rise of ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Barnes |first=Trevor J. |title=Reading economic geography |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-631-23554-5 |page=127 |year=2004}}</ref> ], a modification of ] that is more compatible with ''laissez-faire'' analyses, gained increasing prominence in the capitalist world, especially under the years in office of ] in the United States (1981–1989) and of ] in the United Kingdom (1979–1990). Public and political interest began shifting away from the so-called ] concerns of Keynes's managed capitalism to a focus on individual ], called "remarketized capitalism".<ref name="Fulcher, James 2004">{{cite book |last=Fulcher |first=James |title=Capitalism |edition=1st |location=New York |publisher=] |date=2004}}{{page needed|date=December 2023}}</ref> | |||

| Competition arises when more than one producer is trying to sell the same or similar products to the same buyers. In capitalist theory, competition leads to innovation and more affordable prices. Without competition, a ] or ] may develop. A monopoly occurs when a firm supplies the total output in the market; the firm can therefore limit output and raise prices because it has no fear of competition. A cartel is a group of firms that act together in a monopolistic manner to control output and prices. | |||

| The end of the ] and the ] allowed for capitalism to become a truly global system in a way not seen since before ]. The development of the ] global economy would have been impossible without the fall of ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Gerstle |first=Gary |author-link=Gary Gerstle |date=2022 |title=The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era |url=https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-neoliberal-order-9780197519646?cc=us&lang=en& |location= |publisher=] |pages=10–12 |isbn=978-0-19-751964-6}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Bartel |first=Fritz |date=2022 |title=The Triumph of Broken Promises: The End of the Cold War and the Rise of Neoliberalism |url=https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=978-0-674-97678-8 |location= |publisher=] |pages=5–6, 19 |isbn=978-0-674-97678-8}}</ref> | |||

| Efforts are made by government to prevent the creation of monopolies and cartels. In 1890, the Sherman Anti-Trust Act became the first legislation passed by the U.S. Congress to limit monopolies. <ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/monopoly.asp|title=Monopoly|last=Staff|first=Investopedia|date=24 November 2003|work=Investopedia|access-date=2 March 2017|language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| Harvard Kennedy School economist Dani Rodrik distinguishes between three historical variants of capitalism:<ref>{{citation |last=Rodrik |first=Dani |title=Capitalism 3.0 |date=2009 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46mtqx.23 |work=Aftershocks |volume= |pages=185–193 |editor-last=Hemerijck |editor-first=Anton |publisher=] |jstor=j.ctt46mtqx.23 |isbn=978-90-8964-192-2 |access-date=14 January 2021 |editor2-last=Knapen |editor2-first=Ben |editor3-last=van Doorne |editor3-first=Ellen}}</ref> | |||

| === Profit motive === | |||

| * Capitalism 1.0 during the 19th century entailed largely unregulated markets with a minimal role for the state (aside from national defense, and protecting property rights); | |||

| The ] is a theory in capitalism which posits that the ultimate goal of a business is to make money. Stated differently, the reason for a business's existence is to turn a profit. The profit motive functions on the ], or the theory that individuals tend to pursue what is in their own best interests. Accordingly, businesses seek to benefit themselves and/or their shareholders by maximizing profits. | |||

| * Capitalism 2.0 during the post-World War II years entailed Keynesianism, a substantial role for the state in regulating markets, and strong welfare states; | |||

| * Capitalism 2.1 entailed a combination of unregulated markets, globalization, and various national obligations by states. | |||

| ==== Relationship to democracy ==== | |||

| In capitalist theoretics, the profit motive is said to ensure that resources are being allocated efficiently. For instance, ] ] explains: “If there is no profit in making an article, it is a sign that the labor and capital devoted to its production are misdirected: the value of the resources that must be used up in making the article is greater than the value of the article itself."<ref>Hazlitt, Henry. "The Function of Profits". ''Economics in One Lesson''. Ludwig Von Mises Institute. Web. 22 April 2013.</ref> In other words, profits let companies know whether an item is worth producing. Theoretically in free and competitive markets, maximising profits ensures that resources are not wasted. | |||