| Revision as of 13:51, 20 April 2008 editSennen goroshi (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers5,008 edits →Organ harvesting and extrajudicial execution← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:40, 20 April 2008 edit undoMantisEars (talk | contribs)1,663 edits JS: fixing MoS and other miscellaneous style problemsNext edit → | ||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| {{otheruses4|the People's Republic of China (Communist China)|human rights issues in ], which is officially administrated by the ]|Human rights in the Republic of China|Human Rights in China (HRIC), the non-governmental organization|Human Rights in China (organization)}} | {{otheruses4|the People's Republic of China (Communist China)|human rights issues in ], which is officially administrated by the ]|Human rights in the Republic of China|Human Rights in China (HRIC), the non-governmental organization|Human Rights in China (organization)}} | ||

| {{cquote|No issue in the relations between China and West in the past decades has inspired so much passion as human rights. |

{{cquote|No issue in the relations between China and West in the past decades has inspired so much passion as human rights. Much more is at stake here than moral concerns and hurt national feelings. To many Westerners, the Chinese government appears ultimately untrustworthy on all issues because it is undemocratic. To ], Western human rights pressure seems designed to compromise its legitimacy, and this threat hangs over what might otherwise be considered "normal" disputes on issues like trade and arms sales.<ref>{{cite book | | ||

| title=Human Rights in Chinese Foreign Relations: Defining and Defending National Interests | | |||

| author=Wan, M. and others | | |||

| year=2001 | | |||

| publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press}}</ref>}} | |||

| Since the ], the human rights issue of China has come to the fore. |

Since the ], the human rights issue of China has come to the fore. Multiple sources, including the ] annual ] human rights reports, as well as studies from other groups such as ] and ], have documented the PRC's abuses of ] in violation of internationally recognized norms. | ||

| The PRC government |

The PRC government argues that the notion of human rights should include economic standards of living and measures of health and economic prosperity,<ref name="xinhuanet humanrights">{{cite news | | ||

| url=http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-12/12/content_3908887.htm | | |||

| title=Human rights can be manifested differently | | |||

| publisher=China Daily | | |||

| date=2005-12-12}}</ref> and notes progress in that area.<ref>{{cite web | | |||

| url=http://www.china.org.cn/e-white/prhumanrights1996/index.htm | | |||

| title=Progress in China's Human Rights Cause in 1996 | | |||

| date=March, 1997 | |||

| }}</ref> |

}}</ref> | ||

| Controversial human rights issues in China include policies such as ], their ] and their policy towards ]. | Controversial human rights issues in China include policies such as ], their ] and their policy towards ]. | ||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

| ==The Legal System== | ==The Legal System== | ||

| The Chinese government recognises that there are problems with the current legal system,<ref>{{cite journal | author = "Belkin, Ira" | title = China's Criminal Justice System: A Work in Progress | journal = Washington Journal of Modern China | date = Fall, 2000 | volume = 6 | issue = 2 | url = http://www.law.yale.edu/documents/pdf/Chinas_Criminal_Justice_System.pdf }}</ref> such as: | The Chinese government recognises that there are problems with the current legal system,<ref>{{cite journal | author = "Belkin, Ira" | title = China's Criminal Justice System: A Work in Progress | journal = Washington Journal of Modern China | date = Fall, 2000 | volume = 6 | issue = 2 | url = http://www.law.yale.edu/documents/pdf/Chinas_Criminal_Justice_System.pdf }}</ref> such as: | ||

| * A lack of laws in general, not just ones to protect civil rights. | * A lack of laws in general, not just ones to protect civil rights. | ||

| * A lack of due process. | * A lack of due process. | ||

| * Conflicts of law.<ref>{{cite web |

* Conflicts of law.<ref>{{cite web | ||

| | last = |

| last = | ||

| | first = |

| first = | ||

| | title = Varieties of Conflict of Laws in China |

| title = Varieties of Conflict of Laws in China | ||

| | work = |

| work = | ||

| | publisher = |

| publisher = | ||

| | date = ] | | date = ] | ||

| | url = http://www.humanrights.uio.no/forskning/publ/wp/2002/02/working_paper-Varietie.html | | url = http://www.humanrights.uio.no/forskning/publ/wp/2002/02/working_paper-Varietie.html | ||

| Line 40: | Line 39: | ||

| | last = Yardley | | last = Yardley | ||

| | first = Jim | | first = Jim | ||

| | title = |

| title = A young judge tests China's legal system | ||

| | url=http://www.iht.com/articles/2005/11/28/news/judge.php | | url=http://www.iht.com/articles/2005/11/28/news/judge.php | ||

| | date = ] | | date = ] | ||

| Line 50: | Line 49: | ||

| ==Capital punishment== | ==Capital punishment== | ||

| {{main|Capital punishment in the People's Republic of China}} | {{main|Capital punishment in the People's Republic of China}} | ||

| China had the highest number of executions in 2007<ref>http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/24121932/</ref> |

China had the highest number of executions in 2007<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/24121932/|title=China leads world in executions, report finds}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2008/04/15/world/main4018782.shtml|title=Report: China Leads World In Executions}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/1425570.stm|title=China 'outstrips world' on executions}}</ref> and they had the highest number of executions in 2005{{Fact|date=September 2007}} at 1770 people executed. Between 1994 and 1999, according to the ], China, which has the world's largest population of 1.3 billion people, was ranked seventh in executions ''per capita'', behind ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://web.amnesty.org/library/Index/ENGASA360012004|title=SINGAPORE The death penalty: A hidden toll of executions}}</ref> Amnesty International claims that official figures are much smaller than the real number, stating that in China the statistics are considered State secrets. Amnesty stated that according to various reports, in 2005 3,400 people were executed. In March of that year, a senior member of the ] announced that China executes around 10,000 people per year.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://web.amnesty.org/report2005/chn-summary-eng|title=Amnesty International's report on China}}</ref> | ||

| A total of 68 crimes are punishable by death; capital offenses include non-violent, ]s such as ] and ]. The inconsistent and sometimes corrupt nature of the legal system in mainland China bring into question the fair application of capital punishment there.<ref> |

A total of 68 crimes are punishable by death; capital offenses include non-violent, ]s such as ] and ]. The inconsistent and sometimes corrupt nature of the legal system in mainland China bring into question the fair application of capital punishment there.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://web.amnesty.org/pages/deathpenalty-stats2005-eng|title=The Death Penalty in 2005}}</ref> | ||

| In January 2007, China's state media announced that all death penalty cases will be reviewed by the ]. Since 1983, China's highest court did not review all cases. This marks a return to China's pre-1983 policy. |

In January 2007, China's state media announced that all death penalty cases will be reviewed by the ]. Since 1983, China's highest court did not review all cases. This marks a return to China's pre-1983 policy.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1554379,00.html?cnn=yes|title=China's Message on Executions|author=Jakes, Susan|publisher=Time.com}}</ref> Official figures for 2007-08 suggest death penalties carried out have fallen from over 8000 to around 1000. {{Fact|date=April 2008}} | ||

| ==Organ harvesting and extrajudicial execution== | ==Organ harvesting and extrajudicial execution== | ||

| {{main|Falun Gong and live organ harvesting}} | {{main|Falun Gong and live organ harvesting}} | ||

| In March 2006, allegations were made in the ], a Falun Gong-associated newspaper, of ] on living ] practitioners at the China Traditional Medicine Thrombosis Treatment Center, a Chinese joint-venture company in ], ] co-owned by Country Heights Health Sanctuary of Malaysia, and subject to oversight in ] province. |

In March 2006, allegations were made in the ], a Falun Gong-associated newspaper, of ] on living ] practitioners at the China Traditional Medicine Thrombosis Treatment Center, a Chinese joint-venture company in ], ] co-owned by Country Heights Health Sanctuary of Malaysia, and subject to oversight in ] province. | ||

| According to two witnesses, internal organs of living Falun Gong practitioners have been harvested and sold, and the bodies have been cremated in the hospital's boiler room. The witnesses allege that no prisoner comes out of the Center alive, and that six thousand practitioners have been held captive at the hospital since 2001, two-thirds of whom have died to date. |

According to two witnesses, internal organs of living Falun Gong practitioners have been harvested and sold, and the bodies have been cremated in the hospital's boiler room. The witnesses allege that no prisoner comes out of the Center alive, and that six thousand practitioners have been held captive at the hospital since 2001, two-thirds of whom have died to date. | ||

| On April 14, 2006, |

On April 14, 2006, the ] reported the findings of its investigation, stating that: "U.S. representatives have found no evidence to support allegations that ] has been used as a concentration camp to jail Falun Gong practitioners and harvest their organs."<ref name=state>, U.S. State Department, April 16, 2006</ref> A US Congressional report detailed the State Department's investigation where embassy staff visited the alleged site twice, first time unannounced.<ref name=lum>Thomas Lum, , Congressional Research Service, August 11 2006</ref> | ||

| Dissident ], who immediately sent in investigators, said that the allegations were just hearsay from two witnesses.<ref name=challenge>, South China Morning Post, September 8, 2006</ref> | Dissident ], who immediately sent in investigators, said that the allegations were just hearsay from two witnesses.<ref name=challenge>, South China Morning Post, September 8, 2006</ref> | ||

| The Chinese government accused Falun Gong of fabricating the "Sujiatun concentration camp" issue, reiterating that as a ] Member State, China resolutely abides by the WHO 1991 Guiding Principles on Human Organ Transplants and strictly forbids the sale of human organs. It added that Sujiatun District government carried out an investigation at the hospital and invited local and foreign media, including ] and ]; and two visits were paid by US consular personnel, who confirmed that the hospital was completely incapable of housing more than 6,000 persons; there was no basement for incarcerating practitioners, as alleged; there was simply no way to cremate corpses in secret, continuously, and in large volumes in the hospital's boiler/furnace room. |

The Chinese government accused Falun Gong of fabricating the "Sujiatun concentration camp" issue, reiterating that as a ] Member State, China resolutely abides by the WHO 1991 Guiding Principles on Human Organ Transplants and strictly forbids the sale of human organs. It added that Sujiatun District government carried out an investigation at the hospital and invited local and foreign media, including ] and ]; and two visits were paid by US consular personnel, who confirmed that the hospital was completely incapable of housing more than 6,000 persons; there was no basement for incarcerating practitioners, as alleged; there was simply no way to cremate corpses in secret, continuously, and in large volumes in the hospital's boiler/furnace room. | ||

| In July 2006, ] and ], human rights lawyers, concluded an investigation on behalf of |

In July 2006, ] and ], human rights lawyers, concluded an investigation on behalf of the Coalition to Investigate the Persecution of the Falun Gong in China (CIPFG). US Congressional researcher Thomas Lum criticized the report as relying "largely upon the making of logical inferences" and "inconsistent with the findings of other investigations".<ref name=lum>Thomas Lum, , Congressional Research Service, August 11 2006</ref> Their report gave credence to the allegations of China's harvesting organs from live Falun Gong practitioners. While the Christian Science Monitor states that the report's evidence is circumstantial, but persuasive,<ref>The Monitor's View (August 3, 2006), ''The ]'', retrieved August 6, 2006</ref> the Ottawa Citizen states that the report is not universally accepted and has been criticized by the Chinese government as well as U.S. Congressional Research Service.<ref>Glen McGregor, , ], November 24, 2007</ref> | ||

| ==Ethnic minorities== | ==Ethnic minorities== | ||

| :''See also: ]'' | :''See also: ]'' | ||

| There are 55 ] in China. |

There are 55 ] in China. Article 4 of the Chinese constitution states "All nationalities in the People's Republic of China are equal", and the government has made efforts to improve ethnic education and increased ethnic representation in local government. | ||

| Some policies cause ], where Han Chinese or even ethnic minorities from other regions are treated as second-class citizens in the ethnic region |

Some policies cause ], where Han Chinese or even ethnic minorities from other regions are treated as second-class citizens in the ethnic region.<ref>{{cite web | | ||

| url = http://www.tangben.com/Himalaya.htm | | |||

| author=徐明旭 | | |||

| title=陰謀與虔誠﹕西藏騷亂的來龍去脈 | |||

| ⚫ | }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | | ||

| ⚫ | title=Colonialism, genocide, and Tibet | | ||

| ⚫ | author=Sautman, B. | | ||

| ⚫ | journal=Asian Ethnicity | | ||

| ⚫ | volume=7 | | ||

| ⚫ | number=3 | | ||

| ⚫ | pages=243-265 | | ||

| ⚫ | year=2006 | | ||

| ⚫ | publisher=Routledge | ||

| }}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | <ref>{{cite journal | | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | }}</ref> |

||

| There are also wide-ranging preferential policies (i.e. ]s) in place to promote social and economic developments for ethnic minorities, including preferential employments, political appointments, and business loans | There are also wide-ranging preferential policies (i.e. ]s) in place to promote social and economic developments for ethnic minorities, including preferential employments, political appointments, and business loans.<ref>{{cite journal | | ||

| ⚫ | title=The impact of economic reform on China's minority nationalities | | ||

| <ref>{{cite journal | | |||

| ⚫ | author=Mackerras, C. | | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | journal=Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy | | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | volume=3 | | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| number=1 | | |||

| ⚫ | pages=61-79 | | ||

| number=1 | | |||

| ⚫ | year=1998 | | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | publisher=Routledge | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| </ref> |

</ref> Universities typically have quota reserved for ethnic minorities despite having lower admission test scores.<ref>{{cite journal | | ||

| ⚫ | title=Preferential policies for ethnic minority students in China's college/university admission | | ||

| <ref>{{cite journal | | |||

| ⚫ | author=Tiezhi, W. | | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | journal=Asian Ethnicity | | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| volume=8 | | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| number=2 | | |||

| ⚫ | pages=149-163 | | ||

| number=2 | | |||

| ⚫ | year=2007 | | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | publisher=Routledge | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| </ref> |

</ref> Ethnic minorities are also exempt from the ] which is aimed toward Han Chinese. | ||

| However, the government is harsh toward those that argue for independence or political autonomy, mainly ] and ] in rural provinces in the west of China. |

However, the government is harsh toward those that argue for independence or political autonomy, mainly ] and ] in rural provinces in the west of China. Some groups have used ] to push their agenda.<ref>{{cite journal | | ||

| ⚫ | title=Constituting the Uyghur in US--China Relations: The Geopolitics of Identity Formation in the War on Terrorism | | ||

| <ref>{{cite journal | | |||

| ⚫ | author=Christoffersen, G. | | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | journal=Strategic Insight | | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| volume=2 | | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | year=2002 | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | }}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| }}</ref>. | |||

| Five Chinese Uyghur detainees from the ] ], which was itself known for human rights abuses, were released in June, 2007, but the U.S. refused to return them to China citing the ]'s "past treatment of the Uigur minority".<ref>{{cite news | | Five Chinese Uyghur detainees from the ] ], which was itself known for human rights abuses, were released in June, 2007, but the U.S. refused to return them to China citing the ]'s "past treatment of the Uigur minority".<ref>{{cite news | | ||

| title=Chinese Leave Guantánamo for Albanian Limbo | | |||

| url=http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/10/world/europe/10resettle.html | | |||

| publisher=The New York Times International | | |||

| date=June 10, 2007}}</ref> | |||

| ==="Apartheid" toward Tibetans=== | ==="Apartheid" toward Tibetans=== | ||

| {{npov-section|date=April 18 2008}} | {{npov-section|date=April 18 2008}} | ||

| {{Onesource|date=April 2008}} | {{Onesource|date=April 2008}} | ||

| In 1951, the government of the PRC reclaimed Tibet, and after the ] of 1959, the ] fled to India. |

In 1951, the government of the PRC reclaimed Tibet, and after the ] of 1959, the ] fled to India. In 1991 he alleged that Chinese settlers in Tibet were creating "Chinese Apartheid": | ||

| <blockquote> The new Chinese settlers have created an alternate society: a Chinese apartheid which, denying Tibetans equal social and economic status in our own land, threatens to finally overwhelm and absorb us.<ref name=Dalai>, '']'', April 25, 2006.</ref><ref>United States Congressional Serial Set, United States Government Printing Office, 1993, p. 110.</ref></blockquote> | <blockquote> The new Chinese settlers have created an alternate society: a Chinese apartheid which, denying Tibetans equal social and economic status in our own land, threatens to finally overwhelm and absorb us.<ref name=Dalai>, '']'', April 25, 2006.</ref><ref>United States Congressional Serial Set, United States Government Printing Office, 1993, p. 110.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| In a selection of speeches by the Dalai Lama published in India in 1998, he refers again to a "Chinese apartheid" which he believes denies Tibetans equal social and economic status, and furthers the viewpoint that human rights are violated by discrimination against Tibetans under a policy of apartheid, which the Chinese call "segregation and assimilation"<ref>{{cite journal |title=The Political Philosophy of His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama. Selected Speeches and Writings |

In a selection of speeches by the Dalai Lama published in India in 1998, he refers again to a "Chinese apartheid" which he believes denies Tibetans equal social and economic status, and furthers the viewpoint that human rights are violated by discrimination against Tibetans under a policy of apartheid, which the Chinese call "segregation and assimilation"<ref>{{cite journal |title=The Political Philosophy of His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama. Selected Speeches and Writings | ||

| |publisher=Tibetan Parliamentary and Policy Research Centre}}< /br>"Tibet is being colonized by waves of Chinese immigrants. We are becoming a minority in our own country. The new Chinese settlers have created an alternate society: a Chinese apartheid which, denying Tibetans equal social and economic status in our own land, threatens to finally overwhelm and absorb us. The immediate result has been a round of unrest and reprisal." (pp.65) "Human rights violations in Tibet are among the most serious in the world. Discrimination is practiced in Tibet under a policy of apartheid which the Chinese call "segregation and assimilation." (pp. 248)</ref> | |publisher=Tibetan Parliamentary and Policy Research Centre}}< /br>"Tibet is being colonized by waves of Chinese immigrants. We are becoming a minority in our own country. The new Chinese settlers have created an alternate society: a Chinese apartheid which, denying Tibetans equal social and economic status in our own land, threatens to finally overwhelm and absorb us. The immediate result has been a round of unrest and reprisal." (pp.65) ]"Human rights violations in Tibet are among the most serious in the world. Discrimination is practiced in Tibet under a policy of apartheid which the Chinese call "segregation and assimilation." (pp. 248)</ref> | ||

| According to the ]: | According to the ]: | ||

| Line 143: | Line 138: | ||

| <blockquote>If the matter of Tibet's sovereignty is murky, the question about the PRC's treatment of Tibetans is all too clear. After invading Tibet in 1950, the Chinese communists killed over one million Tibetans, destroyed over 6,000 monasteries, and turned Tibet's northeastern province, Amdo, into a gulag housing, by one estimate, up to ten million people. A quarter of a million Chinese troops remain stationed in Tibet. In addition, some 7.5 million Chinese have responded to Beijing's incentives to relocate to Tibet; they now outnumber the 6 million Tibetans. Through what has been termed Chinese apartheid, ethnic Tibetans now have a lower life expectancy, literacy rate, and per capita income than Chinese inhabitants of Tibet.<ref>Lasater, Martin L. & Conboy, Kenneth J. , ], October 9, 1987.</ref></blockquote> | <blockquote>If the matter of Tibet's sovereignty is murky, the question about the PRC's treatment of Tibetans is all too clear. After invading Tibet in 1950, the Chinese communists killed over one million Tibetans, destroyed over 6,000 monasteries, and turned Tibet's northeastern province, Amdo, into a gulag housing, by one estimate, up to ten million people. A quarter of a million Chinese troops remain stationed in Tibet. In addition, some 7.5 million Chinese have responded to Beijing's incentives to relocate to Tibet; they now outnumber the 6 million Tibetans. Through what has been termed Chinese apartheid, ethnic Tibetans now have a lower life expectancy, literacy rate, and per capita income than Chinese inhabitants of Tibet.<ref>Lasater, Martin L. & Conboy, Kenneth J. , ], October 9, 1987.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| In 2001 representatives of Tibet succeeded in gaining accreditation at a United Nations-sponsored meeting of ]s. On August 29 Jampal Chosang, the head of the Tibetan coalition, stated that China had introduced "a new form of apartheid" in Tibet because "Tibetan culture, religion, and national identity are considered a threat" to China.<ref>Goble, Paul. , ''World Tibet Network News'', , August 31, 2001.</ref> |

In 2001 representatives of Tibet succeeded in gaining accreditation at a United Nations-sponsored meeting of ]s. On August 29 Jampal Chosang, the head of the Tibetan coalition, stated that China had introduced "a new form of apartheid" in Tibet because "Tibetan culture, religion, and national identity are considered a threat" to China.<ref>Goble, Paul. , ''World Tibet Network News'', , August 31, 2001.</ref> The Tibet Society of the ] has called on the British government to "condemn the apartheid regime in Tibet that treats Tibetans as a minority in their own land and which discriminates against them in the use of their language, in education, in the practice of their religion, and in employment opportunities."<ref>, Tibet Vigil UK, June 2002. Accessed June 25, 2006.</ref> | ||

| ==Political freedom== | ==Political freedom== | ||

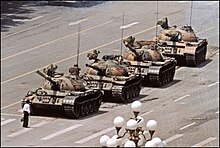

| ] ] by photographer ] (AP), depicting a lone protester who tried to stop the ]'s advancing tanks during the Tiananmen Square protests]] | ] ] by photographer ] (AP), depicting a lone protester who tried to stop the ] advancing tanks during the Tiananmen Square protests]] | ||

| The PRC is known for its intolerance of organized dissent towards the government. |

The PRC is known for its intolerance of organized dissent towards the government. Dissident groups are routinely arrested and imprisoned, often for long periods of time and without trial. One of the most famous dissidents is ], who is known for standing up against the ].<ref name="Scarlet">Zheng, Yi. Sym, T. P. Terrill, Ross. ] (1996). Scarlet Memorial: Tales of Cannibalism in Modern China. Westvuew Press. ISBN 0813326168.</ref> Incidents of torture, forced confessions and forced labour are widely reported. Freedom of assembly and association is extremely limited. The most recent mass movement for political freedom was crushed in the ] in 1989, the estimated death toll of which ranges from about 200 to 10,000 depending on sources.<ref>, ], Retrieved 2007-05-21 {{zh icon}}</ref><ref name="TE">Timperlake, Edward. ] (1999). Red Dragon Rising. Regnery Publishing. ISBN 0895262584</ref> | ||

| <ref>, ], Retrieved 2007-05-21 {{zh icon}}</ref><ref name="TE">Timperlake, Edward. (1999). Red Dragon Rising. Regnery Publishing. ISBN 0895262584</ref> | |||

| Political reforms towards better information disclosure and people empowerment is under way. |

Political reforms towards better information disclosure and people empowerment is under way. "The Chinese government began direct village elections in 1988 to help maintain social and political order in the context of rapid economic reforms. Today, village elections occur in about 650,000 villages across China, reaching 75% of the nation's 1.3 billion people."<ref>{{cite web | | ||

| title=Democratic Village Elections in a Communist Country | | |||

| url=http://www.cartercenter.org/peace/china_elections/village.html | | |||

| publisher=The Carter Center}}</ref> In the year 2008, the city of ], which enjoys the highest per capita GDP in China, is selected for experimentation. Over 70% of the government officials on the district level will be directly elected.<ref>{{cite web|url=www.gd.gov.cn/govpub/zwdt/dfzw/200803/t20080320_44718.htm|title=深圳社区换届直选扩至七成}}</ref> | |||

| ==Freedom of speech== | ==Freedom of speech== | ||

| {{main|Censorship in the People's Republic of China|Government control of the media in the People's Republic of China}} | {{main|Censorship in the People's Republic of China|Government control of the media in the People's Republic of China}} | ||

| Although the 1982 ] guarantees freedom of speech<ref>"Citizens of the People's Republic of China enjoy freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession and of demonstration." </ref> |

Although the 1982 ] guarantees freedom of speech,<ref>"Citizens of the People's Republic of China enjoy freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession and of demonstration." </ref> the Chinese government often uses subversion of state power clause to imprison those who are critical of the government.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23936549/|title=China jails outspoken activist over Tibet views}}</ref> Also, there is very heavy government involvement in the media, with most of the largest media organizations being run directly by the government. Chinese law forbids the advocation of ] or ] for territories Beijing considers under its jurisdiction, as well as public challenge to the CCP's monopoly in ruling China. Thus references to democracy, the Free Tibet movement, ] as an independent state, certain religious organizations and anything remotely questioning the legitimacy of the Communist Party of China are banned from use in publications and ]. PRC journalist ] in her 2004 book ''Media Control in China''<ref> Media Control in China published in Chinese in 2004 by Human Rights in China, New York. Revised edition 2006 published by Liming Cultural Enterprises of Taiwan. Accessed February 4, 2007.</ref> examined government controls on the Internet in China<ref> "The Hijacked Potential of China's Internet", English translation of a chapter in the 2006 revised edition of ''Media Control in China'' published in Chinese by Liming Enterprises of Taiwan in 2006. Accessed February 4, 2007</ref> and on all media. Her book shows how PRC media controls rely on confidential guidance from the Communist Party propaganda department, intense monitoring, and punishment for violators rather than on pre-publication censorship. | ||

| Recently, foreign web portals including Microsoft Live Search, Yahoo! Search, and ''Google Search China''<ref> |

Recently, foreign web portals including Microsoft Live Search, Yahoo! Search, and ''Google Search China''<ref>{{cite web|url=http://blogs.techrepublic.com.com/hiner/?p=525|title=Sanity check: How Microsoft beat Linux in China and what it means for freedom, justice, and the price of software | Tech Sanity Check | TechRepublic.com<!-- Bot generated title -->}}</ref> have come under criticism for aiding in these practices, including banning the word "Democracy" from its chat-rooms in China. Some North American or European films are not given permission to play in Chinese theatres, although piracy of these movies is widespread.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2006/02/23/entertainment/main1340800.shtml|title=China Bans Cartoons With Live Actors|publisher=CBS news|author=Associated Press}}<br />{{cite web |url=http://www.providencephoenix.com/archive/movies/97/07/24/MOON_BAR.html|title=Banned in Beijing|author=Susman, Gary|publisher=The Phoenix (Providence)}}</ref> | ||

| ==Freedom of movement== | ==Freedom of movement== | ||

| {{detail|Hukou}} | {{detail|Hukou}} | ||

| The ] came to power in the late 1940s and instigated a ]. In 1958, Mao set up a residency permit system defining where people could work, and classified an individual as "rural" or "urban" worker.<ref name=Macleod>Macleod, Calum. , '']'', June 10, 2001.</ref> A worker seeking to move from the country to urban areas to take up non-agricultural work would have to apply through the relevant bureaucracies. The number of workers allowed to make such moves was tightly controlled. |

The ] came to power in the late 1940s and instigated a ]. In 1958, Mao set up a residency permit system defining where people could work, and classified an individual as "rural" or "urban" worker.<ref name=Macleod>Macleod, Calum. , '']'', June 10, 2001.</ref> A worker seeking to move from the country to urban areas to take up non-agricultural work would have to apply through the relevant bureaucracies. The number of workers allowed to make such moves was tightly controlled. People who worked outside their authorized domain or geographical area would not qualify for grain rations, employer-provided housing, or health care.<ref name=Wildasin>David Pines, Efraim Sadka, Itzhak Zilcha, ''Topics in Public Economics: Theoretical and Applied Analysis'', Cambridge University Press, 1998, p. 334.</ref> There were controls over education, employment, marriage and so on.<ref name=Macleod/> One purpose is to prevent the possible chaos caused by the predictable large scale urbanization. It is alleged that people of Han nationality in Tibet have a far easier time acquiring the necessary permits to live in urban areas than ethnic Tibetans do.<ref>{{cite web | title = Racial Discrimination in Tibet (2000) | url = http://www.tchrd.org/publications/topical_reports/racial_discrimination-2000/housing/06_restrictions.html | publisher = Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy}}</ref> | ||

| Urban dwellers enjoy a range of social, economic and cultural benefits while peasants, the majority of the Chinese population, are treated as second-class citizens.<ref name=rethinks>Luard, Tim. , '']'', November 10, 2005.</ref> |

Urban dwellers enjoy a range of social, economic and cultural benefits while peasants, the majority of the Chinese population, are treated as second-class citizens.<ref name=rethinks>Luard, Tim. , '']'', November 10, 2005.</ref> | ||

| An article in ], reported in 2000 that although migrants laborers play an important part in spreading wealth in Chinese villages, they are treated "like second-class citizens by a system so discriminatory that it has been likened to apartheid."<ref>Macleod, Calum |

An article in ], reported in 2000 that although migrants laborers play an important part in spreading wealth in Chinese villages, they are treated "like second-class citizens by a system so discriminatory that it has been likened to apartheid."<ref>Macleod, Calum and Macleod, Lijia '' China's migrants bear brunt of bias'', The Washington Times, July 14, 2000. <br />"Sending up to 50% of their earnings home, migrants play an important role in spreading wealth down to the villages. Yet they are still treated like second-class citizens by a system so discriminatory that it has been likened to apartheid."</ref> Another author making similar comparison is Anita Chan, in which she furthers that China's household registration and temporary residence permit system has created a situation analogous to the passbook system in apartheid South Africa, which were designed to regulate the supply of cheap labor.<ref name=Chan>Chan, Anita, ''China's Workers under Assault: The Exploitation of Labor in a Globalizing Economy'', Introduction chapter, M.E. Sharpe. 2001, ISBN 0-765-60358-6</ref> | ||

| Abolition was proposed in 11 provinces, mainly along the developed eastern coast. The law has already been changed such that migrant workers no longer faced summary arrest, after a widely publicised incident in 2003, when a university-educated migrant died in Guangdong province. This particular scandal was exposed by a Beijing law lecturer, Mr Xu, who claims it spelt the end of the hukou system. He further believes that, at least in most smaller cities, the system had already been abandoned. Mr Xu continued: "Even in big cities like Beijing and Shanghai, it has almost lost its function".<ref name=Luard>Luard, Tim. , '']'', November 10, 2005. Retrieved 5th Aug 2007.</ref> |

Abolition was proposed in 11 provinces, mainly along the developed eastern coast. The law has already been changed such that migrant workers no longer faced summary arrest, after a widely publicised incident in 2003, when a university-educated migrant died in Guangdong province. This particular scandal was exposed by a Beijing law lecturer, Mr Xu, who claims it spelt the end of the hukou system. He further believes that, at least in most smaller cities, the system had already been abandoned. Mr Xu continued: "Even in big cities like Beijing and Shanghai, it has almost lost its function".<ref name=Luard>Luard, Tim. , '']'', November 10, 2005. Retrieved 5th Aug 2007.</ref> | ||

| ;Special administrative regions | ;Special administrative regions | ||

| Line 178: | Line 172: | ||

| In November 2005 Jiang Wenran, acting director of the China Institute at the ], said this system has been ''"one of the most strictly enforced 'apartheid' social structures in modern world history."'' He stated ''"Urban dwellers enjoy a range of social, economic and cultural benefits while peasants, the majority of the Chinese population, are treated as second-class citizens."'' | In November 2005 Jiang Wenran, acting director of the China Institute at the ], said this system has been ''"one of the most strictly enforced 'apartheid' social structures in modern world history."'' He stated ''"Urban dwellers enjoy a range of social, economic and cultural benefits while peasants, the majority of the Chinese population, are treated as second-class citizens."'' | ||

| The discrimination enforced by the ''hukou'' system became particularly onerous in the 1980s after hundreds of millions of migrant laborers were forced out of state corporations and co-operatives.<ref name=TheStar>"Chinese apartheid: Migrant labourers, numbering in hundreds of millions, who have been ejected from state concerns and co-operatives since the 1980s as China instituted "socialist capitalism", have to have six passes before they are allowed to work in provinces other than their own. In many cities, private schools for migrant labourers are routinely closed down to discourage migration." "From politics to health policies: why they're in trouble", '']'', February 6, 2007.</ref> The system classifies workers as "urban" or "rural",<ref name=Wildasin/><ref name=ChanSenser/> and attempts by workers classified as "rural" to move to urban centers were tightly controlled by the Chinese bureaucracy, which enforced its control by denying access to essential goods and services such as grain rations, housing, and health care,<ref name=Wildasin/> and by regularly closing down migrant workers' private schools.<ref name=TheStar/> The ''hukuo'' system also enforced ] similar to those in South Africa,<ref name=Waddington>"The application of these regulations is reminiscent of apartheid South Africa's hated pass laws. Police carry out raids periodically to round up those tho do not possess a temporary residence permit. Those without papers are placed in detention centres and then removed from cities." Waddington, Jeremy. ''Globalization and Patterns of Labour Resistance'', Routledge, 1999, p. 82.</ref><ref name=Chan>"The permit system controls in a similar way to the passbook system under apartheid.Most migrant workers live in crowded dormitories provided by the factories or in shanties. Their transient existence is precarious and exploitative. The discrimination against migrant workers in the Chinese case is not racial, but the control mechanisms set in place in the so-called free labor market to regulate the supply of cheap labor, the underlying economic logic of the system, and the abusive consequences suffered by the migrant workers, share many of the characteristics of the apartheid system." Chan, Anita. ''China's Workers Under Assault: The Exploitation of Labor in a Globalizing Economy'', M.E. Sharpe, 2001, p. 9.</ref> with "rural" workers requiring six passes to work in provinces other than their own,<ref name=TheStar/> and periodic police raids which rounded up those without permits, placed them in detention centers, and deported them.<ref name=Waddington/> As in South Africa, the restrictions placed on the mobility of migrant workers were pervasive,<ref name=TheStar/> and transient workers were forced to live a precarious existence in company dormitories or ], and suffering abusive consequences.<ref name=Chan/> |

The discrimination enforced by the ''hukou'' system became particularly onerous in the 1980s after hundreds of millions of migrant laborers were forced out of state corporations and co-operatives.<ref name=TheStar>"Chinese apartheid: Migrant labourers, numbering in hundreds of millions, who have been ejected from state concerns and co-operatives since the 1980s as China instituted "socialist capitalism", have to have six passes before they are allowed to work in provinces other than their own. In many cities, private schools for migrant labourers are routinely closed down to discourage migration." "From politics to health policies: why they're in trouble", '']'', February 6, 2007.</ref> The system classifies workers as "urban" or "rural",<ref name=Wildasin/><ref name=ChanSenser/> and attempts by workers classified as "rural" to move to urban centers were tightly controlled by the Chinese bureaucracy, which enforced its control by denying access to essential goods and services such as grain rations, housing, and health care,<ref name=Wildasin/> and by regularly closing down migrant workers' private schools.<ref name=TheStar/> The ''hukuo'' system also enforced ] similar to those in South Africa,<ref name=Waddington>"The application of these regulations is reminiscent of apartheid South Africa's hated pass laws. Police carry out raids periodically to round up those tho do not possess a temporary residence permit. Those without papers are placed in detention centres and then removed from cities." Waddington, Jeremy. ''Globalization and Patterns of Labour Resistance'', Routledge, 1999, p. 82.</ref><ref name=Chan>"The permit system controls ] in a similar way to the passbook system under apartheid.Most migrant workers live in crowded dormitories provided by the factories or in shanties. Their transient existence is precarious and exploitative. The discrimination against migrant workers in the Chinese case is not racial, but the control mechanisms set in place in the so-called free labor market to regulate the supply of cheap labor, the underlying economic logic of the system, and the abusive consequences suffered by the migrant workers, share many of the characteristics of the apartheid system." Chan, Anita. ''China's Workers Under Assault: The Exploitation of Labor in a Globalizing Economy'', M.E. Sharpe, 2001, p. 9.</ref> with "rural" workers requiring six passes to work in provinces other than their own,<ref name=TheStar/> and periodic police raids which rounded up those without permits, placed them in detention centers, and deported them.<ref name=Waddington/> As in South Africa, the restrictions placed on the mobility of migrant workers were pervasive,<ref name=TheStar/> and transient workers were forced to live a precarious existence in company dormitories or ], and suffering abusive consequences.<ref name=Chan/> Anita Chan furthers that China's household registration and temporary residence permit system has created a situation analogous to the passbook system in apartheid South Africa, which were designed to regulate the supply of cheap labor.<ref name=Chan/><ref>"HIGHLIGHT: Discrimination against rural | ||

| migrants is China's apartheid: Certainly, the discrimination against the country-born is China's form of apartheid. It is an offence against human rights on a much bigger scale than the treatment of the tiny handful of dissidents dogged enough to speak up against the state." "Country Cousins", '']'', April 8, 2000.</ref><ref name=Macleod>Macleod, Calum. , '']'', June 10, 2001.</ref><ref>"...China's apartheid-like system of residency permits." Yao, Shunli. , '']'', June, 2002.</ref><ref name=Wildasin>"As in South Africa under ''apartheid'', households in China faced severe restrictions on mobility during the Mao period. The household registration system (''hukou'') system... specified where people could work and, in particular, classified workers as rural or urban workers. A worker seeking to move from rural agricultural employment to urban non-agricultural work would have to apply through the relevant bureaucracies, and the number of workers allowed to make such moves was tightly controlled. The enforcement of these controls was closely intertwined with state controls on essential goods and services. For instance, unauthorized workers could not qualify for grain rations, employer-provided housing, or health care." Wildasin, David E. "Factor mobility, risk, inequality, and redistribution" in David Pines, Efraim Sadka, Itzhak Zilcha, ''Topics in Public Economics: Theoretical and Applied Analysis'', Cambridge University Press, 1998, p. 334.</ref><ref name=ChanSenser>"China's apartheid-like household registration system, introduced in the 1950s, still divides the population into two distinct groups, urban and rural." Chan, Anita & Senser, Robert A. , '']'', March / April 1997.</ref> |

migrants is China's apartheid: Certainly, the discrimination against the country-born is China's form of apartheid. It is an offence against human rights on a much bigger scale than the treatment of the tiny handful of dissidents dogged enough to speak up against the state." "Country Cousins", '']'', April 8, 2000.</ref><ref name=Macleod>Macleod, Calum. , '']'', June 10, 2001.</ref><ref>"...China's apartheid-like system of residency permits." Yao, Shunli. , '']'', June, 2002.</ref><ref name=Wildasin>"As in South Africa under ''apartheid'', households in China faced severe restrictions on mobility during the Mao period. The household registration system (''hukou'') system... specified where people could work and, in particular, classified workers as rural or urban workers. A worker seeking to move from rural agricultural employment to urban non-agricultural work would have to apply through the relevant bureaucracies, and the number of workers allowed to make such moves was tightly controlled. The enforcement of these controls was closely intertwined with state controls on essential goods and services. For instance, unauthorized workers could not qualify for grain rations, employer-provided housing, or health care." Wildasin, David E. "Factor mobility, risk, inequality, and redistribution" in David Pines, Efraim Sadka, Itzhak Zilcha, ''Topics in Public Economics: Theoretical and Applied Analysis'', Cambridge University Press, 1998, p. 334.</ref><ref name=ChanSenser>"China's apartheid-like household registration system, introduced in the 1950s, still divides the population into two distinct groups, urban and rural." Chan, Anita & Senser, Robert A. , '']'', March / April 1997.</ref> | ||

| David Whitehouse divides what he describes as "Chinese apartheid" into three distinct phases: The first phase occurred during the ] phase of China's economy, from around 1953 to the death of ] in 1976. The second "]" phase lasted from 1978 to 2001, and the third lasted from 2001 to the present. During the first phase, the exploitation of rural labor, the passbook system, and in particular the non-portable rights associated with one's status, created what Whitehouse calls "an apartheid system". As with South Africa, the ruling party made some concessions to rural workers to make life in rural areas "survivable... if not easy or pleasant". During the second phase, as China transitioned from state capitalism to market capitalism, export-processing zones were created in city suburbs, where mostly female migrants worked under oppressive ] conditions. The third phase was characterized by the weakening of the ''hukou'' controls; by 2004 the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture counted over 100 million people registered as "rural" working in cities.<ref name=Whitehouse> Whitehouse, David. {{PDFlink||73.5 ]<!-- application/pdf, 75324 bytes -->}}, Paper delivered at the Colloquium on Economy, Society and Nature, sponsored by the Centre for Civil Society at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, March 2, 2006. Retrieved August 1, 2007.</ref> | David Whitehouse divides what he describes as "Chinese apartheid" into three distinct phases: The first phase occurred during the ] phase of China's economy, from around 1953 to the death of ] in 1976. The second "]" phase lasted from 1978 to 2001, and the third lasted from 2001 to the present. During the first phase, the exploitation of rural labor, the passbook system, and in particular the non-portable rights associated with one's status, created what Whitehouse calls "an apartheid system". As with South Africa, the ruling party made some concessions to rural workers to make life in rural areas "survivable... if not easy or pleasant". During the second phase, as China transitioned from state capitalism to market capitalism, export-processing zones were created in city suburbs, where mostly female migrants worked under oppressive ] conditions. The third phase was characterized by the weakening of the ''hukou'' controls; by 2004 the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture counted over 100 million people registered as "rural" working in cities.<ref name=Whitehouse> Whitehouse, David. {{PDFlink||73.5 ]<!-- application/pdf, 75324 bytes -->}}, Paper delivered at the Colloquium on Economy, Society and Nature, sponsored by the Centre for Civil Society at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, March 2, 2006. Retrieved August 1, 2007.</ref> | ||

| Au Loong-yu, Nan Shan, and Zhang Ping of the Committee for Asian Women argue this system oppresses women more severely than men,<ref>"We further identify seven elements of the repressive regime at the national, municipal and local levels, and argue that the combined results of these elements have given rise to a kind of spatial and social apartheid which systematically discriminates against the rural population, with women being the most oppressed." Au Loong-yu, Nan Shan, Zhang Ping. {{PDFlink||2.01 ]<!-- application/pdf, 2112402 bytes -->}}, Committee for Asian Women, May 2007, p. 1.</ref> and see seven distinct elements giving rise to what they describe as "he regime of spatial and social apartheid" which keeps rural Chinese in their subordinate status: | Au Loong-yu, Nan Shan, and Zhang Ping of the Committee for Asian Women argue this system oppresses women more severely than men,<ref>"We further identify seven elements of the repressive regime at the national, municipal and local levels, and argue that the combined results of these elements have given rise to a kind of spatial and social apartheid which systematically discriminates against the rural population, with women being the most oppressed." Au Loong-yu, Nan Shan, Zhang Ping. {{PDFlink||2.01 ]<!-- application/pdf, 2112402 bytes -->}}, Committee for Asian Women, May 2007, p. 1.</ref> and see seven distinct elements giving rise to what they describe as "]he regime of spatial and social apartheid" which keeps rural Chinese in their subordinate status: | ||

| # The repressive regime at the factory level; | # The repressive regime at the factory level; | ||

| # the paramilitary forces at local level; | # the paramilitary forces at local level; | ||

| Line 198: | Line 192: | ||

| === "Pass System" treatment of migrant workers === | === "Pass System" treatment of migrant workers === | ||

| "Rural" workers would require six passes to work in provinces other than their own,<ref name=TheStar/> and periodic police raids which rounded up those without permits, placed them in detention centers, and deported them.<ref name=Waddington/> Restrictions placed on the mobility of migrant workers were pervasive,<ref name=TheStar/> and some transient workers were forced to live a precarious existence in company dormitories or ], and suffering abusive consequences.<ref name=Chan/> The system, which has targeted China's 800 million rural peasants for decades, has been described by journalists Peter Alexander and Anita Chan as "China's apartheid".<ref>"Country Cousins", '']'', April 6, 2000.</ref><ref name=ChanSenser>"China's apartheid-like household registration system, introduced in the 1950s, still divides the population into two distinct groups, urban and rural." Chan, Anita & Senser, Robert A. , '']'', March / April 1997.</ref> |

"Rural" workers would require six passes to work in provinces other than their own,<ref name=TheStar/> and periodic police raids which rounded up those without permits, placed them in detention centers, and deported them.<ref name=Waddington/> Restrictions placed on the mobility of migrant workers were pervasive,<ref name=TheStar/> and some transient workers were forced to live a precarious existence in company dormitories or ], and suffering abusive consequences.<ref name=Chan/> The system, which has targeted China's 800 million rural peasants for decades, has been described by journalists Peter Alexander and Anita Chan as "China's apartheid".<ref>"Country Cousins", '']'', April 6, 2000.</ref><ref name=ChanSenser>"China's apartheid-like household registration system, introduced in the 1950s, still divides the population into two distinct groups, urban and rural." Chan, Anita & Senser, Robert A. , '']'', March / April 1997.</ref> | ||

| According to Peter Alexander and Anita Chan, China's export-oriented growth has been based on the labor of poorly paid and treated migrant workers, using a ] similar to the one used in South Africa's apartheid, in which massive abuses of human rights have been observed.<ref name=Peter&Chan>Alexander, Peter, & Chan, Anita , Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 30.4 (2004)<br /> China's household registration system (HRS) maintains a rigid distinction between China's rural population, that is people who have a rural hukou (household registration), and urban residents, who have an urban hukou. Movement of rural people into the cities is restricted, and they require a permit to stay and work temporarily in any urban area. If caught without these permits, people with a rural hukou could be placed in a detention centre, fined, and deported back to their home village or home town (that is, 'endorsed out', to borrow a South African expression). Those with a rural hukou who obtain a temporary employment permit to work in an urban area are not entitled to the pensions, schooling, unemployment benefits, etc. enjoyed by those who have an urban hukou. There are, in short, some obvious and significant similarities between the two countries, but a closer examination is required before we can consider equating China's pass system with what operated in apartheid South Africa." " The combination of these four factors may explain why China has developed a quasi-apartheid pass system. The fact that it has such a system underlines the reality that China's export-oriented economic growth has been built, in large measure, on the labour of poorly paid and appallingly treated migrant workers. In China today, as in apartheid South Africa, the pass system is associated with massive abuses of human rights, and its retention should be opposed."</ref> | According to Peter Alexander and Anita Chan, China's export-oriented growth has been based on the labor of poorly paid and treated migrant workers, using a ] similar to the one used in South Africa's apartheid, in which massive abuses of human rights have been observed.<ref name=Peter&Chan>Alexander, Peter, & Chan, Anita , Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 30.4 (2004)<br /> China's household registration system (HRS) maintains a rigid distinction between China's rural population, that is people who have a rural hukou (household registration), and urban residents, who have an urban hukou. Movement of rural people into the cities is restricted, and they require a permit to stay and work temporarily in any urban area. If caught without these permits, people with a rural hukou could be placed in a detention centre, fined, and deported back to their home village or home town (that is, 'endorsed out', to borrow a South African expression). Those with a rural hukou who obtain a temporary employment permit to work in an urban area are not entitled to the pensions, schooling, unemployment benefits, etc. enjoyed by those who have an urban hukou. There are, in short, some obvious and significant similarities between the two countries, but a closer examination is required before we can consider equating China's pass system with what operated in apartheid South Africa." ]" The combination of these four factors may explain why China has developed a quasi-apartheid pass system. The fact that it has such a system underlines the reality that China's export-oriented economic growth has been built, in large measure, on the labour of poorly paid and appallingly treated migrant workers. In China today, as in apartheid South Africa, the pass system is associated with massive abuses of human rights, and its retention should be opposed."</ref> | ||

| An article in ], reported in 2000 that although migrant laborers play an important part in spreading wealth in Chinese villages, they are treated "like second-class citizens by a system so discriminatory that it has been likened to apartheid."<ref>Macleod, Calum |

An article in ], reported in 2000 that although migrant laborers play an important part in spreading wealth in Chinese villages, they are treated "like second-class citizens by a system so discriminatory that it has been likened to apartheid."<ref>Macleod, Calum and Macleod, Lijia '' China's migrants bear brunt of bias'', The Washington Times, July 14, 2000. <br />"Sending up to 50% of their earnings home, migrants play an important role in spreading wealth down to the villages. Yet they are still treated like second-class citizens by a system so discriminatory that it has been likened to apartheid."</ref> | ||

| The Chinese embassy in South Africa posted a letter to the editor of ] dated ], 2007 , under the title ''Article on China presents racism rumours as fact'', |

The Chinese embassy in South Africa posted a letter to the editor of ] dated ], 2007 , under the title ''Article on China presents racism rumours as fact'', in which a reader stated that "It's pure incitement to proclaim 'Chinese apartheid' in reference to migrant labour being kept out of the cities."<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.chinese-embassy.org.za/eng/zt/thirdeye/t299146.htm|publisher=Embassy of The People's Republic of China in the Republic of South Africa"|title= Article on China presents racism rumours as fact}}</ref> | ||

| ==Religious freedom== | ==Religious freedom== | ||

| {{main|Freedom of religion in the People's Republic of China}} | {{main|Freedom of religion in the People's Republic of China}} | ||

| During the ] (1966-1976), particularly the ] campaign, religious affairs of all types were persecuted and discouraged by the Communists with many religious buildings looted and destroyed. |

During the ] (1966-1976), particularly the ] campaign, religious affairs of all types were persecuted and discouraged by the Communists with many religious buildings looted and destroyed. Since then, there have been efforts to repair, reconstruct and protect historical and cultural religious sites.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://wwwistp.murdoch.edu.au/publications/e_public/Case%20Studies_Asia/tourchin/tourchin.htm|title=murdoch edu}}</ref> Critics say that not enough has been done to repair or restore damaged and destroyed sites.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://beijing.usembassy-china.org.cn/hr_report2005tib.html|title=Beijing usembassy-china}}</ref> | ||

| The 1982 Constitution technically guarantees its citizens the right to believe in any religion, however this is not to be confused with the general concept of "Freedom of Religion" as is commonly referred to in the West as the right to practice religion in any way you see fit without government interference. |

The 1982 Constitution technically guarantees its citizens the right to believe in any religion, however this is not to be confused with the general concept of "Freedom of Religion" as is commonly referred to in the West as the right to practice religion in any way you see fit without government interference.<ref>"Citizens of the People's Republic of China enjoy freedom of religious belief. No state organ, public organization or individual may compel citizens to believe in, or not to believe in, any religion; nor may they discriminate against citizens who believe in, or do not believe in, any religion. The state protects normal religious activities. No one may make use of religion to engage in activities that disrupt public order, impair the health of citizens or interfere with the educational system of the state. Religious bodies and religious affairs are not subject to any foreign domination."</ref> This freedom is subject to restrictions, as all religious groups must be registered with the government and are prohibited from having loyalties outside of China. In addition, the communist government continually tries to maintain control over not only religious content, but also leadership choices such as the choosing of bishops and other spiritual leaders. Considering all party leaders must be communist, the ability of such officials to intelligently choose religious leaders is highly questionable. For example, the recently appointed Bishop in China was not appointed by the Pope as has been the Catholic Church's practice up until this time.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.asianews.it/index.php?l=en&art=9856&size=A|title=The new Bishop of Beijing is elected}}</ref> The government argues that such restriction is necessary to prevent foreign political influence eroding Chinese sovereignty, though groups affected by this deny that they have any desire to interfere in China's political affairs. This has led to an effective prohibition on those religious practices that by definition involve allegiance to a foreign spiritual leader or organization, (e.g. ] - see ]) although tacit allegiance to such individuals and bodies inside these groups is not uncommon. "Unregistered religious groups ... experience varying degrees of official interference, harassment, and repression."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.persecution.com.au/countries/country.asp?cid=chin|title=Persecution.com.au}}</ref> | ||

| Particularly troubling is the lack of transparency involved in recently chosen Tibetan spiritual leaders. China attempts to intervene in the reincarnation of Tibetan spiritual leaders and has indicated it will oversee the search for a new leader after the Dalai Lama passes away. Beijing indicates that spiritual leaders must obtain approval before they reincarnate.<ref> |

Particularly troubling is the lack of transparency involved in recently chosen Tibetan spiritual leaders. China attempts to intervene in the reincarnation of Tibetan spiritual leaders and has indicated it will oversee the search for a new leader after the Dalai Lama passes away. Beijing indicates that spiritual leaders must obtain approval before they reincarnate.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/article2194682.ece|title=China tells living Buddhas to obtain permission before they reincarnate}}</ref> Even more troubling is China's dealings with previously identified reincarnations of past leaders. For example, the child who was identified as the new Panchen Lama by Tibetan spiritual leaders was first detained by Chinese authorities and then disappeared. The child has not been seen since, has spent the last 12 years in detention and has effectively been robbed of his childhood. Repeated requests have been made by visitor heads of state, including the Canadian prime minister.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/04/23/AR2006042301349.html|title=World's youngest political prisoner turns 17}}</ref> Reporters and tourists visiting Tibet note that monasteries are subject to video surveillance. Other examples of the lack of religious freedom are:<ref name="icywind">{{cite web|url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B00E5DF1630F93BA25752C1A96E958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all|title=Icy Wind From Beijing Chills the Monks of Tibet}}</ref> | ||

| 1) quotas instituted by Beijing on the number of monks to reduce the spiritual population | 1) quotas instituted by Beijing on the number of monks to reduce the spiritual population | ||

| 2) Forced denunciation of the Dalai Lama as a spiritual leader or expulsion | 2) Forced denunciation of the Dalai Lama as a spiritual leader or expulsion | ||

| Line 219: | Line 213: | ||

| 5) Restriction of religious study before age 18. | 5) Restriction of religious study before age 18. | ||

| Numerous other instances of detention for unpatriotic acts have also been recorded, an example of this would be the detention of monks celebrating the reception of the Medal of Honor by a Tibetan monk.<ref> |

Numerous other instances of detention for unpatriotic acts have also been recorded, an example of this would be the detention of monks celebrating the reception of the Medal of Honor by a Tibetan monk.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tchrd.org/press/2007/pr20071023.html|title=Forcing silence in Tibet as Dalai Lama receives US Congressional Gold Medal}}</ref> | ||

| The effects have been drastic, whereas one large temple in Tibet once was a place of worship for over 10,000 monks, it is now only home to 600 and Beijing now restricts total membership in any monastery to 700.<ref |

The effects have been drastic, whereas one large temple in Tibet once was a place of worship for over 10,000 monks, it is now only home to 600 and Beijing now restricts total membership in any monastery to 700.<ref name="icycold" /> | ||

| Another problem is that members of the Communist Party have to be ] according to the Party's constitution. As Party membership is required for many high level careers, being openly religious can limit one's economic prospects. | Another problem is that members of the Communist Party have to be ] according to the Party's constitution. As Party membership is required for many high level careers, being openly religious can limit one's economic prospects. | ||

| The |

The government of the ] tries to maintain tight control over all religions, so the only legal Christian Churches (] and ]) are those under the ] control. It has been claimed by many that the teachings in the state-approved Churches are at least monitored and sometimes modified by the Party. | ||

| Because ] operate outside government regulations and restrictions, their members and leaders are sometimes harassed by local government officials. This persecution may take the form of a prison sentence or, more commonly, reeducation through labour. Heavy fines also are not uncommon, with personal effects being confiscated in lieu of payment if this is refused or unavailable. Unlike Falun Gong, however, house churches have not officially been outlawed, and since the 1990s, there has been increasing official tolerance of house churches. Most observers believe that the harassment of house churches by government officials arises less from an ideological opposition to religion and support of atheism than out of fears of a center of popular mobilization outside the control of the Communist Party of China. {{Fact|date=April 2008}} | Because ] operate outside government regulations and restrictions, their members and leaders are sometimes harassed by local government officials. This persecution may take the form of a prison sentence or, more commonly, reeducation through labour. Heavy fines also are not uncommon, with personal effects being confiscated in lieu of payment if this is refused or unavailable. Unlike Falun Gong, however, house churches have not officially been outlawed, and since the 1990s, there has been increasing official tolerance of house churches. Most observers believe that the harassment of house churches by government officials arises less from an ideological opposition to religion and support of atheism than out of fears of a center of popular mobilization outside the control of the Communist Party of China. {{Fact|date=April 2008}} | ||

| Line 236: | Line 230: | ||

| {{Original research|date=April 2008}} | {{Original research|date=April 2008}} | ||

| On July 20, 1999, the government of the ] (PRC) banned |

On July 20, 1999, the government of the ] (PRC) banned ] and began a nationwide crackdown on the practice, except in the special administrative regions of ] and ]. The actions taken by the Chinese government against Falun Gong are referred to as "persecution" by some overseas governments, international human rights organizations, and scholars. | ||

| The crackdown began following seven years of widespread popularity and rapid growth of the practice within mainland China.<ref name="Ownbyworld">David Ownby, "The Falun Gong in the New World," European Journal of East Asian Studies, Sep2003, Vol. 2 Issue 2, p 306</ref><ref name=ching>p. 2</ref> A New York Times article reported that there were 70 million practitioners in China in 1998, a figure coming from the Chinese government.<ref>Faison, Seth (April 27, 1999) ''New York Times'', retrieved June 10, 2006</ref><ref>Kahn, Joseph (April 27, 1999) ''New York Times'', retrieved June 14, 2006</ref> A series of appeals and petitions made by practitioners to the authorities in 1999, in particular the 10,000 person gathering at Zhongnanhai on April 25, eventually led to the decision to outlaw and persecute Falun Gong.<ref name=XIX>American Asian Review, Vol. XIX, no. 4, Winter 2001, p. 12</ref> A World Journal article suggested that certain high-level Party officials had wanted to crack down on the practice for a several years, but lacked sufficient pretext until this time.<ref name=XIX /> Jiang Zemin is often considered to be largely personally responsible for the final decision, both by Falun Gong and academics. Possible motives include personal jealously of Li Hongzhi,<ref>Dean Peerman, , Christian Century, |

The crackdown began following seven years of widespread popularity and rapid growth of the practice within mainland China.<ref name="Ownbyworld">David Ownby, "The Falun Gong in the New World," European Journal of East Asian Studies, Sep2003, Vol. 2 Issue 2, p 306</ref><ref name=ching>p. 2</ref> A New York Times article reported that there were 70 million practitioners in China in 1998, a figure coming from the Chinese government.<ref>Faison, Seth (April 27, 1999) ''New York Times'', retrieved June 10, 2006</ref><ref>Kahn, Joseph (April 27, 1999) ''New York Times'', retrieved June 14, 2006</ref> A series of appeals and petitions made by practitioners to the authorities in 1999, in particular the 10,000 person gathering at Zhongnanhai on April 25, eventually led to the decision to outlaw and persecute Falun Gong.<ref name=XIX>American Asian Review, Vol. XIX, no. 4, Winter 2001, p. 12</ref> A World Journal article suggested that certain high-level Party officials had wanted to crack down on the practice for a several years, but lacked sufficient pretext until this time.<ref name=XIX /> Jiang Zemin is often considered to be largely personally responsible for the final decision, both by Falun Gong and academics. Possible motives include personal jealously of Li Hongzhi,<ref>Dean Peerman, , Christian Century, August 10, 2004</ref> anger, and ideological struggle.<ref name=Saich>Tony Saich, ''Governance and Politics in China,'' Palgrave Macmillan; 2nd Ed edition (27 Feb 2004)</ref> Others implicate the nature of Communist Party rule and a perceived challenge to it as causes for the crackdown.<ref name=lestz>Michael Lestz, , Religion in the News, Fall 1999, Vol. 2, No. 3, Trinity College, Massachusetts</ref> The government explanation for the crackdown was that Falun Gong was "jeopardising social stability," and "engaged in illegal activities."<ref name=ban>], , ], July 22, 1999</ref> Legislation to outlaw Falun Gong was created and enforced retroactively.<ref name="Leung" /> | ||

| The Party mobilized every aspect of society to become involved in the persecution, including the media apparatus, police force, army, education system, families and workplaces.<ref name=wildgrass>Johnson, Ian, ''Wild Grass: three portraits of change in modern china'', Vintage (March 8, 2005)</ref> An extra-constitutional body, the "6-10 Office" was created to do what Forbes describes as "<nowiki></nowiki> the terror campaign."<ref name=morais>Morais, Richard C., ''Forbes'', February 9, 2006, retrieved ] ]</ref> |

The Party mobilized every aspect of society to become involved in the persecution, including the media apparatus, police force, army, education system, families and workplaces.<ref name=wildgrass>Johnson, Ian, ''Wild Grass: three portraits of change in modern china'', Vintage (March 8, 2005)</ref> An extra-constitutional body, the "6-10 Office" was created to do what Forbes describes as "<nowiki>]</nowiki> the terror campaign."<ref name=morais>Morais, Richard C., ''Forbes'', February 9, 2006, retrieved ] ]</ref> The campaign was driven by large-scale propaganda through television, newspaper, radio and internet.<ref name=Leung> Leung, Beatrice (2002) 'China and Falun Gong: Party and society relations in the modern era', Journal of Contemporary China, 11:33, 761 – 784</ref> Families and workplaces were urged to cooperate with the government's position on Falun Gong, while practitioners themselves were subject to various coercive measures to have them recant their beliefs.<ref name=dangerous>Mickey Spiegel, , Human Rights Watch, 2002, accessed Sept 28, 2007</ref> | ||

| Amnesty International states that the persecution is politically motivated and a restriction of fundamental freedoms. Particular concerns have been raised over reports of torture, illegal imprisonment including forced labour, psychiatric abuses,<ref> (23 March 2000) , Amnesty International</ref><ref>United Nations (], ]) , retrieved ], ]</ref> and since early 2006, allegations of systematic organ harvesting from living Falun Gong practitioners.<ref name=theage>Reuters, AP (July 8, 2006),''The Age'', retrieved July 7, 2006</ref> |

Amnesty International states that the persecution is politically motivated and a restriction of fundamental freedoms. Particular concerns have been raised over reports of torture, illegal imprisonment including forced labour, psychiatric abuses,<ref> (23 March 2000) , Amnesty International</ref><ref>United Nations (], ]) , retrieved ], ]</ref> and since early 2006, allegations of systematic organ harvesting from living Falun Gong practitioners.<ref name=theage>Reuters, AP (July 8, 2006),''The Age'', retrieved July 7, 2006</ref> | ||

| Protests in Beijing were frequent for the first few years following the 1999 edict, though these protests have largely been eradicated.<ref name=wildgrass/> Falun Gong practitioners' presence in mainland China has become more low-profile, often involving methods of informing the general populace through overnight letterbox drops of pro-Falun Gong CD-ROMs. Practitioners have occasionally hacked into state television channels to broadcast pro-Falun Gong materials. Outside of mainland China, practitioners are active in appealing to the governments, media, and people of their respective countries about the situation in China. | Protests in Beijing were frequent for the first few years following the 1999 edict, though these protests have largely been eradicated.<ref name=wildgrass/> Falun Gong practitioners' presence in mainland China has become more low-profile, often involving methods of informing the general populace through overnight letterbox drops of pro-Falun Gong CD-ROMs. Practitioners have occasionally hacked into state television channels to broadcast pro-Falun Gong materials. Outside of mainland China, practitioners are active in appealing to the governments, media, and people of their respective countries about the situation in China. | ||

| Line 248: | Line 242: | ||

| ==One-Child Policy== | ==One-Child Policy== | ||

| {{main|One-Child Policy}} | {{main|One-Child Policy}} | ||

| China's ] policy, known widely as the ], is seen as ineffective or morally objectionable by many. However, the Chinese government argues that this policy is a necessary solution for their ]<ref>, 2004-04-24, Retrieved 2007-11-16</ref> problem. Such critics argue that it contributes to ], human rights violations, female infanticide, abandonment and sex selective ]s. These are believed to be relatively commonplace in some areas of the country, despite being illegal and punishable by fines and jail time.<ref> |

China's ] policy, known widely as the ], is seen as ineffective or morally objectionable by many. However, the Chinese government argues that this policy is a necessary solution for their ]<ref>, 2004-04-24, Retrieved 2007-11-16</ref> problem. Such critics argue that it contributes to ], human rights violations, female infanticide, abandonment and sex selective ]s. These are believed to be relatively commonplace in some areas of the country, despite being illegal and punishable by fines and jail time.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.voanews.com/english/archive/2005-09/2005-09-26-voa6.cfm?CFID=17626358&CFTOKEN=49646296|title=Voanews}}</ref> This is thought to have been a significant contribution to the gender imbalance in mainland China, where there is a 118 to 100 ratio of male to female children reported.<ref>"Gender imbalance in China could take 15 years to correct" http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2007/jan/24/china.international; Retrieved 2008-04-19.</ref><ref>"China grapples with legacy of its ‘missing girls’" http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/5953508; Retrieved 2008-04-19.</ref><ref>"China vows to halt growing gender imbalance" http://english.people.com.cn/200701/23/eng20070123_343739.html; Retrieved 2008-04-19.</ref> Forced abortions and sterilizations have also been reported.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cnn.com/WORLD/asiapcf/9806/11/china.abortion/|title=Cnn.com China abortion}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.chron.com/disp/story.mpl/front/5094395.html|title= Chinese victims of forced late-term abortion fight back|accessdate=2007-08-30 |date= 2007-08-30|publisher= Associated Press|author= Olesen, Alexa}}</ref> | ||

| It is also argued that the one child policy is not effective enough to justify its costs, and that the dramatic decrease in Chinese fertility started before the program began in 1979 for unrelated factors. |

It is also argued that the one child policy is not effective enough to justify its costs, and that the dramatic decrease in Chinese fertility started before the program began in 1979 for unrelated factors. The policy seems to have had little impact on rural areas (home to about 80% of the population), where birth rates never dropped below 2.5 children per female.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.overpopulation.com/faq/Population_Control/one_child.html|title=Over population one child}}</ref> Nevertheless, the Chinese government and others estimate that at least 250 million births have been prevented by the policy.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/941511.stm|title=news.bbc.co.uk}}</ref> | ||

| In 2002, the laws related to the One-Child Policy were amended to allow ethnic minorities and Chinese living in rural areas to have more than one child. |

In 2002, the laws related to the One-Child Policy were amended to allow ethnic minorities and Chinese living in rural areas to have more than one child. The policy was generally not enforced in those areas of the country even before this. The policy has been relaxed in urban areas to allow people who were single children to have two children.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://geography.about.com/od/populationgeography/a/onechild.htm|title=Geography.about.com population}}</ref> | ||

| ==Other human rights issues== | ==Other human rights issues== | ||