| Revision as of 14:59, 2 September 2009 view sourceRick Norwood (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users21,613 edits →Modern ideology: Begin work on a large number of small sections which need to be organized and reference. Please help.← Previous edit | Revision as of 23:19, 3 September 2009 view source Introman (talk | contribs)1,688 edits deleted original research assumption that Marcus Aurelius statement is representative of liberalism, much less that that it encapsulates liberalism such that it should head the whole articleNext edit → | ||

| (14 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| {{Liberalism sidebar |expanded=all}} | {{Liberalism sidebar |expanded=all}} | ||

| Liberalism (from the Latin ''liberalis'', suitable for a free man) is the belief in the importance of individual freedom. This belief is widely accepted today throughout the world, and was recognized as an important value by many philosophers throughout history. |

'''Liberalism''' (from the Latin ''liberalis'', suitable for a free man) is the belief in the importance of individual freedom. This belief is widely accepted today throughout the world, and was recognized as an important value by many philosophers throughout history. | ||

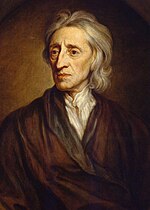

| Modern liberalism has its roots in the ] and rejects many ] assumptions that dominated most earlier theories of government, such as the ], hereditary status, ], and economic ].<ref name="howe">Free Trade and Liberal England, 1846-1946 By Anthony Howe</ref><ref name="freeden">Ideologies and Political Theory By Michael Freeden</ref><ref name="economichistory">The Cambridge Economic History of Europe by ], ], ], ], ], ], ]</ref> ] is often credited with the philosophical foundations of modern liberalism. He wrote "no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions."<ref name = "locke">{{cite book | last = Locke | first = John | title = ] (10th edition) | publisher = ] | date = 1690 | url = http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext05/trgov10h.htm | accessdate = January 21, 2009}}</ref> | Modern liberalism has its roots in the ] and rejects many ] assumptions that dominated most earlier theories of government, such as the ], hereditary status, ], and economic ].<ref name="howe">Free Trade and Liberal England, 1846-1946 By Anthony Howe</ref><ref name="freeden">Ideologies and Political Theory By Michael Freeden</ref><ref name="economichistory">The Cambridge Economic History of Europe by ], ], ], ], ], ], ]</ref> ] is often credited with the philosophical foundations of modern liberalism. He wrote "no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions."<ref name = "locke">{{cite book | last = Locke | first = John | title = ] (10th edition) | publisher = ] | date = 1690 | url = http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext05/trgov10h.htm | accessdate = January 21, 2009}}</ref> | ||

| Line 431: | Line 431: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| {{Link FA|ru}} | {{Link FA|ru}} | ||

Revision as of 23:19, 3 September 2009

This article discusses the ideology of liberalism. Local differences in its meaning are listed in Liberalism worldwide. For other uses, see Liberal.Liberalism (from the Latin liberalis, suitable for a free man) is the belief in the importance of individual freedom. This belief is widely accepted today throughout the world, and was recognized as an important value by many philosophers throughout history.

Modern liberalism has its roots in the Age of Enlightenment and rejects many foundational assumptions that dominated most earlier theories of government, such as the Divine Right of Kings, hereditary status, established religion, and economic protectionism. John Locke is often credited with the philosophical foundations of modern liberalism. He wrote "no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions."

In the 17th Century, liberal ideas began to influence governments in Europe, in nations such as The Netherlands, Switzerland, England and Poland, but they were strongly opposed, often by armed might, by those who favored absolute monarchy and established religion. In the 18th Century, in America, the first modern liberal state was founded, without a monarch or a hereditary aristocracy. The American Declaration of Independence, includes the words (which echo Locke) "all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to insure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed."

Today, most nations accept the ideals of freedom. But Liberalism comes in many forms. According to James L. Richardson, in Contending Liberalisms in World Politics: Ideology and Power, there are three main divisions within liberalism. The first is elitism versus democracy. The second is economic; whether freedom is best served by a free market or by a regulated market. The third is the question of extending liberal principles to the disadvantaged.

Etymology and historical usage

The earliest recorded governments in which free citizens played an important role were the democracy in Athens and the republic in Rome. The Athenian lawgiver Solon wrote, "...men who wore the shameful brand of slavery and suffered the hideous moods of brutal masters -- all these I freed." The Roman historian Titus Livius, in his History of Rome From Its Foundation, describes the struggle of the plebeians to win freedom from the domination of the patricians. Marcus Aurelius, in his Meditations, writes about "the idea of a polity administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech, and the idea of a kingly government which respects most of all the freedom of the governed". Largely dormant during the Middle Ages, the struggle for freedom began again during the Italian Renaissance in the conflict between supporters of free city-states on the one hand and supporters of the Pope or of the Holy Roman Emperor on the other. Niccolò Machiavelli, in his Discourses on Livy, laid down the principles of republican government.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) indicates that the word liberal has long been in the English language with the meanings of "befitting free men, noble, generous" as in liberal arts; also with the meaning "free from restraint in speech or action", as in liberal with the purse, or liberal tongue, usually as a term of reproach but, beginning 1776–88 imbued with a more favorable sense by Edward Gibbon and others to mean "free from prejudice, tolerant."

The first English language use to mean "tending in favor of freedom and democracy," according to the OED, dates from about 1801 and comes from the French libéral, "originally applied in English by its opponents (often in Fr. form and with suggestions of foreign lawlessness)." An early English language citation: "The extinction of every vestige of freedom, and of every liberal idea with which they are associated."

The editors of the Spanish Constitution of 1812, drafted in Cádiz, may have been the first to use the word liberal in a political sense as a noun. They named themselves the Liberales, to express their opposition to the absolutist power of the Spanish monarchy.

Liberalism in this sense became a widespread ideal during Age of Enlightenment, when philosophers such as John Locke in England and Jean-Jacques Rousseau in France articulated the struggle for freedom in terms of the Rights of Man.

The American War of Independence established the first nation to craft a constitution based on the concept of liberal government, especially the idea that governments rule by the consent of the governed. The more moderate bourgeois elements of the French Revolution tried to establish a government based on liberal principles, but the radical Robespierre seized power, leading to the Reign of Terror and a reactionary movement which restored the monarchy.

The main thrust of liberalism was freedom from despotic rule and the replacement of aristocracy by social equality, but it also had an economic side. Adam Smith, in The Wealth of Nations (1776), enunciated the liberal principles of free trade.

Liberal philosophy

There were many precursors to liberalism, including certain aspects of the Magna Carta, which reduced the power of the English monarch, and medieval Islamic ethics, which allowed some freedom of religion. But most histories of modern liberal thought begin with John Locke (1632 - 1704).

Locke's Two Treatises on Government (1689) discussed two fundamental liberal ideas: intellectual liberty, including freedom of conscience, which he further expounded in the same year in A Letter Concerning Toleration, and economic liberty, the right to have and use property. These early liberal ideas were tentative (and published anonymously). Locke did not extend religious freedom to Roman Catholics and considered slaves to be lawful property. Locke developed further the earlier idea of natural rights, a forerunner of the modern conception of human rights, which Locke saw as the rights to life, liberty and property (Locke's actual words are "life, health, liberty, or possessions")..

Another 17th-century Englishman, John Lilburne (also known as Freeborn John), argued for basic human rights which he called freeborn rights, the natural rights that every human being is born with, as opposed to rights bestowed by government or by human law.

On the European continent, the doctrine of laws restraining even monarchs was expounded by Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, whose The Spirit of the Laws argues that "Better is it to say, that the government most conformable to nature is that which best agrees with the humour and disposition of the people in whose favour it is established," rather than accept as natural the mere rule of force. Following in his footsteps, political economist Jean-Baptiste Say and Destutt de Tracy were ardent exponents of the "harmonies" of the market, and in all probability it was they who coined the term laissez-faire. This evolved into the physiocrats, and to the political economy of Rousseau.

The late French enlightenment saw two figures who would have tremendous influence on later liberal thought: Voltaire, who argued that the French should adopt constitutional monarchy and disestablish the Second Estate, and Rousseau, who argued for a natural freedom for mankind.

Rousseau also argued the importance of a concept that appears repeatedly in the history of liberal thought, namely, the social contract. He rooted this in the nature of the individual and asserted that each person knows their own interest best. His assertion that man is born free, and that education was sufficient to restrain him within society, rocked the monarchical society of his age. His ideas were a key element in the declaration of the National Assembly during the French Revolution, and in the thinking of Americans such as Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson. In his view the unity of a state came from the concerted action of consent, or the "national will". This unity of action would allow states to exist without being chained to pre-existing social orders, such as aristocracy.

The "Scottish Enlightenment" included the writers David Hume and Adam Smith.

David Hume's contributions were many and varied, but most important was his assertion that fundamental rules of human behavior would overwhelm attempts to restrict or regulate them. In A Treatise of Human Nature, 1739-1740, he disparaged mercantilism and the accumulation of gold and silver by governments. He argued that prices were related to the quantity of money, and that hoarding gold and issuing paper money would only lead to inflation.

Although Adam Smith is the most famous of the economic liberal thinkers, he was not without antecedents. The physiocrats in France had proposed studying systematically political economy and the self organizing nature of markets. Benjamin Franklin wrote in favor of the freedom of American industry in 1750. In Sweden-Finland the period of liberty and parliamentary government from 1718 to 1772 produced a Finnish parliamentarian, Anders Chydenius, who was one of the first to propose free trade and unregulated industry, in The National Gain, 1765. His impact has proven to be lasting particularly in the Nordic area, but it also had a powerful effect in later developments elsewhere.

Adam Smith (1723–1790) expounded the theory that individuals could structure both moral and economic life without direction from the state, and that nations would be strongest when their citizens were free to follow their own initiative. He advocated an end to feudal and mercantile regulations, to state-granted monopolies and patents, and he promulgated "laissez-faire" economics. In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, 1759, he developed a theory of motivation that tried to reconcile human self-interest and an unregulated social order. In The Wealth of Nations, 1776, he argued that the market, under certain conditions, would naturally regulate itself and would produce more than the heavily restricted markets that were the norm at the time. He assigned to government the role of taking on tasks which could not be entrusted to the profit motive, such as preventing individuals from using force or fraud to disrupt competition, trade, or production. His theory of taxation was that governments should levy taxes only in ways which did not harm the economy, and that "The subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities; that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state." He agreed with Hume that capital, not gold, is the wealth of a nation.

Immanuel Kant was strongly influenced by both Hume's empiricism and continental rationalism. His most important contributions to liberal thinking are in the realm of ethics, particularly his assertion of the categorical imperative. Kant argued that received systems of reason and morals were subordinate to natural law, and that, therefore, attempts to stifle this basic law would meet with failure. His idealism would become increasingly influential, since it asserted that there were fundamental truths upon which systems of knowledge could be based. This meshed well with the ideas of the English Enlightenment about natural rights.

Liberal revolutions

The philosophers of liberalism wrote in a political framework of monarchies, and in societies in which the class system and an established church were the norm. The first European nation to officially permit freedom of religion was Poland, during the reign of Zygmut I and Zybmut II (1506 - 1572). According to Adam Zamoyski in The Polish Way, "They encouraged every form of creative activity throughout the most dynamic period of Europe's artistic development, and they graciously allowed their subjects to do anything they wanted -- except butcher each other in the name of religion." Holland also showed a degree of religious tolerance that was rare in an age of religious warfare.

England had a brief experiment with republican government, when the Wars of the Three Kingdoms led to the establishment of a Commonwealth between 1649 and 1660, but the idea that ordinary human beings could structure their own affairs was suppressed with the Restoration.

The American Revolution of 1776 established the first government based on liberal principles without a monarch or an aristocracy. The French Revolution attempted to do the same, but radicals took power, leading to the Reign of Terror, and a reaction which restored the monarchy.

The American Declaration of Independence proclaimed the liberal ideals of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams were instrumental in creating a country whose constitution was based on liberal principles. But this new government allowed slavery and limited the franchise to landed White males.

James Madison was prominent among the next generation of political theorists in America, arguing that in a republic self-government depended on setting "interest against interest", thus providing protection for the rights of minorities, particularly economic minorities. The American constitution contained a system of checks and balances: federal government balanced against states' rights; executive, legislative, and judicial branches; and a bicameral legislature. The goal was to insure liberty by preventing the concentration of power in the hands of any one man. Standing armies were held in suspicion, and the belief was that the militia would be enough for defense, along with a navy maintained by the government to protect American trading vessels.

The French Revolution overthrew monarchy, aristocracy, and an established Roman Catholic Church. Representatives of the Third Estate set themselves up as a "National Assembly", and claimed for themselves the right to speak for the French people. During the first few years the revolution was guided by liberal ideas, but the transition from revolt to stability was to prove more difficult than the similar American transition. In addition to native Enlightenment traditions, some leaders of the early phase of the revolution, such as Lafayette, had fought in the U.S. War of Independence against Britain, and brought home Anglo-American liberal ideas, but later, under the leadership of Maximilien Robespierre, a Jacobin faction greatly centralized power and dispensed with most aspects of due process, resulting in the Reign of Terror. Instead of an ultimately republican constitution, Napoleon Bonaparte rose from Director, to Consul, to Emperor. On his death bed he confessed "They wanted another Washington", meaning a man who could militarily establish a new state, without desiring a dynasty. Despite the eventual restoration of the monarchy, in many ways the French Revolution went farther than the American Revolution in establishing liberal ideals. The French Constitution of 1793 established universal male suffrage and included a far reaching Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, paralleling the United States Bill of Rights. One of the side-effects of Napoleon's military campaigns was to carry these ideas throughout Europe, and some were adopted by those opposing Napoleon's advances.

The examples of United States and France were followed in many other countries. Following the usurpation of the Spanish monarchy by Napoleon's forces in 1808, autonomist and independence movements began in Spain, Portugal and Latin America, which often turned to liberal ideas as alternatives to the monarchical-clerical corporatism of the old regime and the colonial era. Movements such as those led by the Cádiz Cortes in Spain and by Simón Bolívar in the Andean countries aspired to constitutional government, individual rights, and free trade. The struggle between liberals and corporatist conservatives continued for the rest of the century in Portugal, Spain and Latin America, with anti-clerical liberals such as Benito Juárez of Mexico attacking the traditional role of the Roman Catholic Church.

The transition to liberal society in Europe sometimes came through revolutionary or secessionist violence, and there were many liberal revolutions and revolts throughout Europe in the first half of the 19th century. In Britain, however, and in many other nations, the process was driven more by politics than revolution, even when the process was not entirely tranquil. The anti-clerical violence during the French Revolution was seen by opponents of liberalism at the time,and for most of the 19th century as proof that liberal doctrine led to mob rule, and that a strong monarch was necessary for stability.

Liberal notions moved from being proposals for reform of existing governments to demands for change. The American Revolution and the French Revolution added democracy to the list of liberal values. The idea that the people were sovereign and capable of making all necessary laws and enforcing them went beyond the conceptions of the Enlightenment. Instead of merely asserting the rights of individuals within the state, all of the state's powers were derived from the nature of man (natural law), given by God (supernatural law), or by contract ("the just consent of the governed"). This made compromise with previously autocratic orders far less likely, and the resulting violence was justified by the monarchists as necessary to restore order.

The contractual nature of liberal thought to this point must be stressed. One of the basic ideas of the first wave of thinkers in the liberal tradition was that individuals made agreements and owned property. This may not seem a radical notion today, but at the time most property laws defined property as belonging to a family or to a particular figure within it, such as the "head of the family". Obligations were based on feudal ties of loyalty and personal fealty, rather than an exchange of goods and services. Gradually, the liberal tradition introduced the idea that voluntary consent and voluntary agreement were the basis for legitimate government and law. This view was further advanced by Rousseau with his notion of a social contract.

Between 1774 and 1848, there were several waves of revolutions, each revolution demanding greater and greater primacy for individual rights. The revolutions placed increasing value on self-governance. This could lead to secession – a particularly important concept in the American Revolution and in the revolutions which ended Spanish control over much of her colonial empire in the Americas. European liberals, particularly after the French Constitution of 1793, thought that democracy, considered as majority rule by propertyless men, would be a danger to private property, and favored a franchise limited to those with a certain amount of property. Later liberal democrats, like de Tocqueville, disagreed. In countries where feudal property arrangements still held sway, liberals generally supported unification as the path to liberty. The strongest examples of this are Germany and Italy, which at the time were not nations but aggregations of independent states. As part of this revolutionary program, the importance of education, a value repeatedly stressed from Erasmus onward, became more and more central to the idea of liberty.

Liberal parties in many European monarchies agitated for parliamentary government, increased representation, expansion of the franchise where present, and the creation of a counterweight to monarchical power. This political liberalism was often driven by economic liberalism and the desire to end feudal privileges, guild or royal monopolies, restrictions on ownership, and laws against the full range of corporate and economic arrangements being developed in other countries. To one degree or another, these forces were seen even in autocracies such as Turkey, Russia and Japan. As the Russian Empire crumbled under the weight of economic failure and military defeat, it was the liberal parties who took control of the Duma, and in 1905 and 1917 began revolutions against the government. Later Piero Gobetti would formulate a theory of "Liberal Revolution" to explain what he felt was the radical element in liberal ideology. Another example of this form of liberal revolution is from Ecuador where Eloy Alfaro in 1895 lead a "radical liberal" revolution that secularized the state, opened marriage laws, engaged in the development of infrastructure and the economy.

In the United States, there were two major liberal revolutions in the 19th Century, the first political, the second leading to Civil War. In 1829, populist candidate and war hero Andrew Jackson was elected to the first of two terms as the 7th president of the United States. During the era of Jacksonian democracy, the franchise was extended to include, for the first time, all White adult male citizens. Jackson also attempted to change economic policy in the direction of laissez-faire economics, in what came to be known as the "Bank War". Jacksonian democracy came to an end during turmoil surrounding the anti-slavery movement. Before the Civil War, in the North as well as the South, Blacks were not allowed to vote, to serve on juries, to go to school, to testify in court in any case involving a White person, or to hold public office. The Civil War led to the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed those slaves in states in rebellion, and to the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the US Constitution, which abolished slavery throughout the United States, and extended equal rights to people of all races, in theory if not always in practice.

Modern Liberalism

By the beginning of the 20th century, political liberalism had become the norm throughout the West, but economic liberalism had resulted in a vast concentration of wealth, with the majority of mankind living in a state of extreme poverty. The economic world was shaken by a series of depressions. Freedom, which had been threatened by autocratic governments, was now threatened by the despotism of the rich.

Communism offered a revolutionary alternative to liberalism, promising freedom to the masses and a more just distribution of wealth. The political history of the 20th Century can be seen as a cold war between liberal democracy and communism, though other enemies of liberalism, fascism and more recently Islamism, have also struggled for dominance.

Liberalism's answer to communism came in the form of social liberalism, as proposed by the British philosopher T. H. Green. His writing stressed the interdependence of human beings, and the need for a government that would promote freedom by providing health care and education, and fight the forces of prejudice and ignorance.

Another brand of liberalism arose at this time in opposition to social liberalism, called social Darwinism, as discussed in the writing of another British philosopher, Herbert Spencer. Where Green stressed community and interdependence, Spencer stressed individuality and self-interest. In his view, government should get out of the way, or at most serve as a "night-watchman", and allow human beings freedom to compete. In this competition, the weak would die and the strong survive, to the eventual improvement of the human race.

While the social liberals strove to eliminate the poverty that made communism attractive, the followers of social Darwinism considered that a weak response, and favored war as the only sure method of destroying communism. Communist parties were outlawed in many parts of Europe, and communist demonstrations violently suppressed. The communists also chose violence as the best method of attaining their ends, and communist revolutions were successful in much of Eastern Europe and in China.

At the same time that communist revolutions were going on in Russia and China, the social liberals were making major changes in the West. They recognized the power of capitalism to produce wealth, and believed that communism would fail on economic rather than military grounds. At the same time, they argued that the benefits of the wealth produced by capitalism should be shared with the general population, and not left in the hands of the few. They sponcered programs of civic improvement: the building of schools, hospitals, public transportation, and sewage systems. During times of depression, these programs provided jobs for the unemployed, who would otherwise either starve or be a threat to orderly society.

The Great Depression

Main article: Great Depression

For ten years,from 1929 to the start of World War II, the West was in the grip of what has come to be called The Great Depression. In Europe, the turmoil and poverty of depression contributed not only to the success of communist revolutions in Eastern Europe, but also to the rise of a new power, fascism, which held that dictatorship was the only form of government strong enough to combat communism.

The British economist John Maynard Keynes offered a plan that he claimed could end the Great Depression without fascism or communism. He argued that government, while leaving the market free in most respects, could manage the money supply in a way that would smooth out the highs and lows of the boom and bust cycle that had plagued capitalism since the 19th Century.

In the United States, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt instituted the New Deal, which eased the suffering of the unemployed with a variety of measures, such as the WPA and social security. He also supported laws to encourage trade unions and to regulate banking. These measures did not, however, end the Great Depression, which continued until the vast increase in government spending when the nation moved to a wartime economy leading up to .

During the war, liberalism and communism become uneasy allies to defeat fascism, but almost as soon as the war ended, they renewed their hostile stance, although the cold war stopped short of actual warfare.

Totalitarianism

In the mid-20th century, liberalism began to define itself in opposition to totalitarianism. The term was first used by Giovanni Gentile to describe the socio-political system set up by Benito Mussolini. Joseph Stalin would apply it to German Nazism, and after the war it became a descriptive term for what liberalism considered the common characteristics of fascist, Nazi and Marxist-Leninist regimes. Totalitarian regimes sought and tried to implement absolute centralized control over all aspects of society, in order to achieve prosperity and stability. These governments often justified such absolutism by arguing that the survival of their civilization was at risk. Opposition to totalitarian regimes acquired great importance in liberal and democratic thinking, and they were often portrayed as trying to destroy liberal democracy. On the other hand, the opponents of liberalism strongly objected to the classification that unified mutually hostile fascist and communist ideologies and considered them fundamentally different.

In Italy and Germany, nationalist governments linked corporate capitalism to the state, and promoted the idea that their nations were culturally and racially superior, and that conquest would give them their "rightful" place in the world. The propaganda machines of these countries argued that democracy was weak and incapable of decisive action, and that only a strong leader could impose necessary discipline. In Soviet Union, the ruling communists banned private property, claiming to act for the sake of economic and social justice, and the government had full control over the planned economy. The regime insisted that personal interests be linked and inferior to those of the society, of class, which was ultimately an excuse for persecuting both oppositions as well as dissidents within the communists ranks as well as arbitrary use of severe penal code.

The rise of totalitarianism became a lens for liberal thought. Many liberals began to analyze their own beliefs and principles, and came to the conclusion that totalitarianism arose because people in a degraded condition turn to dictatorships for solutions. From this, it was argued that the state had the duty to protect the economic well being of its citizens. As Isaiah Berlin said, "Freedom for the wolves means death for the sheep." This growing body of liberal thought argued that reason requires a government to act as a balancing force in economics.

Other liberal interpretations on the rise of totalitarianism were quite contrary to the growing body of thought on government regulation in supporting the market and capitalism. This included Friedrich Hayek's work, The Road to Serfdom. He argued that the rise of totalitarian dictatorships was the result of too much government intervention and regulation upon the market which caused loss of political and civil freedoms. Hayek also saw these economic controls being instituted in the United Kingdom, the United States, and in Canada and warned against these "Keynesian" institutions, believing that they can and will lead to the same totalitarian governments "Keynesians liberals" were attempting to avoid. Hayek saw authoritarian regimes such as the fascist, Nazis, and communists, as the same totalitarian branch; all of which sought the elimination or reduction of economic freedom. To him the elimination of economic freedom brought about the elimination of political freedom. Thus Hayek believes the differences between Nazis and communists are only rhetorical.

Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman stated that economic freedom is a necessary condition for the creation and sustainability of civil and political freedoms. Hayek believed the same totalitarian outcomes could occur in Britain (or anywhere else) if the state sought to control the economic freedom of the individual with the policy prescriptions outlined by people like Dewey, Keynes, or Roosevelt.

One of the most influential critics of totalitarianism was Karl Popper. In The Open Society and Its Enemies he defended liberal democracy and advocated open society, in which the government can be changed without bloodshed. Popper argued that the process of the accumulation of human knowledge is unpredictable and that the theory of ideal government cannot possibly exist. Therefore, the political system should be flexible enough so that governmental policy would be able to evolve and adjust to the needs of the society; in particular, it should encourage pluralism and multiculturalism.

After World War II

In much of the West, expressly liberal parties were caught between "conservative" parties on one hand, and "labour" or social democratic parties on the other hand. For example, the UK Liberal Party became a minor party. The same process occurred in a number of other countries, as the social democratic parties took the leading role in the Left, while pro-business conservative parties took the leading role in the Right.

The post-war period saw the dominance of social liberalism. Linking modernism and progressivism to the notion that a populace in possession of rights and sufficient economic and educational means would be the best defense against totalitarian threats, the liberalism of this period took the stance that by enlightened use of liberal institutions, individual liberties could be maximized, and self-actualization could be reached by the broad use of technology. Liberal writers in this period include economist John Kenneth Galbraith, philosopher John Rawls and sociologist Ralf Dahrendorf. A dissenting strain of thought developed that viewed any government involvement in the economy as a betrayal of liberal principles. Calling itself "libertarianism," this movement was centered around such schools of thought as Austrian Economics.

The debate between personal liberty and social optimality occupies much of the theory of liberalism since the Second World War, particularly centering around the questions of social choice and market mechanisms required to produce a "liberal" society. One of the central parts of this argument concerns Kenneth Arrow's General Possibility Theorem. This thesis states that there is no consistent social choice function which satisfies unbounded decision making, independence of choices, Pareto optimality, and non-dictatorship. In short, according to the thesis which includes the problem of liberal paradox, it is not possible to have unlimited liberty, a maximum amount of utility, and an unlimited range of choices at the same time. Another important argument within liberalism is the importance of rationality in decision making whether people make decisions rationally or irrationally. There is also the question of the relationship, if any, between freedom and material inequality.

Libertarians phrase this debate in terms of positive rights and negative rights. By positive rights they mean such things as the "right" to an education, the "right" to health care, or the "right" to a minimum wage. By negative rights they mean such things as the "right" to enforce contracts, the "right" of protection against lawlessness, and the "right" to be left alone by the government as long as you honor contracts and obey the law, and that laws should be limited to preventing violence and theft, and enforcing contracts.

Utilitarians use different language for the same ideas. Instead of the word "rights" they use the word "good", and argue that an educated, healthy populace, able to support itself by its labor, is for the "good" of society.

After the 1970s, the liberal pendulum swung away from the idea of increasing the role of government, and towards a greater use of the free market and laissez-faire principles. In theory, many of the old pre-World War I ideas were making a comeback. In fact, all governments increased in both power and spending, under liberal and conservative leaders alike.

In part this was a reaction to the triumphalism of the dominant forms of liberalism of the time, but as well it was rooted in a foundation of liberal philosophy: suspicion of the state. Even liberal institutions can be misused to restrict rather than promote liberty. Increasing emphasis on the free market emerged with economist Milton Friedman in the United States, and with members of the Austrian School in Europe. Their argument was that regulation and government involvement in the economy was a slippery slope, that any would lead to more, and that more was difficult to remove.

Varieties of liberalism

The impact of liberalism on the modern world is profound. The ideas of individual liberty, personal dignity, free expression, religious tolerance, private property, universal human rights, transparency of government, limitations on government power, popular sovereignty, national self-determination, privacy, "enlightened" and "rational" policy, the rule of law, respect for science, fundamental equality, a free market economy, and free trade were all radical notions some 250 years ago. Liberal democracy, in its typical form of multiparty political pluralism, has spread to much of the world. Today all are accepted as the goals of policy in most nations, even where there is a wide gap between what governments say and what they do. Not only liberal parties honor these principles, but social democrats, conservatives, and Christian Democrats at least pay lip service to them as well. Most debate is within a liberal framework. This has led to the word "liberal" being used in many different ways. One difference is between elitism and democracy, another is between a free market and a regulated market, a third is the question of extending liberal principles to the disadvantaged.

Economic liberalism

Key liberal thinkers, such as Lujo Brentano, Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse, Thomas Hill Green, John Maynard Keynes, Bertil Ohlin and John Dewey, described how a government should intervene in the economy to protect liberty while avoiding socialism. These liberals developed the theory of social liberalism (also "new liberalism," not to be confused with present-day neoliberalism). Social liberals rejected both radical capitalism and the revolutionary elements of the socialist school. John Maynard Keynes, in particular, had a significant impact on liberal thought throughout the world. The Liberal Party in Britain, particularly since Lloyd George's People's Budget, was heavily influenced by Keynes, as was the Liberal International, the Oxford Liberal Manifesto of 1947 of the world organization of liberal parties. In the United States and in Canada, the influence of Keynesianism on Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal and on William Lyon Mackenzie King has led social liberalism to be identified with American liberalism and Canadian liberalism.

Other liberals, including F. A. Hayek, Milton Friedman, and Ludwig von Mises, argued that the great depression was not a result of "laissez-faire" capitalism but a result of too much government intervention and regulation upon the market. In Friedman's work "Capitalism and Freedom" he discussed government regulation that occurred before the great depression, including heavy regulations upon banks that prevented them, he argued, from reacting to the markets' demand for money. Furthermore, the U.S. Federal government had created a fixed currency pegged to the value of gold. At first the pegged value created a massive surplus of gold, but later the pegged value was too low, which created an equally massive migration of gold from the U.S. Friedman and Hayek both believed that this inability to react to currency demand created a run on the banks that the banks were no longer able to handle, and that the currency demand combined with fixed exchange rates between the dollar and gold both worked to cause the Great Depression, by creating, and then not fixing, deflationary pressures. He further argued in this thesis, that the government inflicted more pain upon the American public by first raising taxes, then by printing money to pay debts (thus causing inflation), the combination of which helped to wipe out the savings of the middle class.

In 1974 Hayek was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics for, among other reasons, his theory of business cycles and his conception of the effects of monetary and credit policies, and for being "one of the few economists who gave warning of the possibility of a major economic crisis before the great crash came in the autumn of 1929."

Role of the State

From the beginning of liberal thinking, there was a vigorous debate over the proper role of the state. For example, in the newly founded United States government, a government based on liberal principles, Thomas Paine accused George Washington of trying to set himself up as a king, while John Adams supported Washington, arguing that a strong federal government was necessary to prevent mob rule. Benjamin Franklin discussed the question of what measures a liberal government should take to protect the poor.

This debate has continued throughout modern history. To what extent should a liberal government take an active role in the welfare of its citizens? By the end of the 19th century, some liberals asserted that, in order to be free, individuals needed access to food, shelter, and education, and government protection from exploitation. In 1911, L.T. Hobhouse published Liberalism, which summarized these ideas, including qualified acceptance of government intervention in the economy, and the collective right to equality in dealings, what he called "just consent."

Opposed to these changes was a strain of liberalism which became increasingly anti-government, in some cases adopting anarchism. Gustave de Molinari in France and Herbert Spencer in England were prominent examples of this trend.

The debate continues today.

Natural rights vs. utilitarianism vs. contractarianism

In 1810, the German Wilhelm von Humboldt developed the modern concepts of liberalism in his book The Limits of State Action. John Stuart Mill popularized and expanded these ideas in On Liberty (1859) and other works. He opposed collectivist tendencies while still placing emphasis on quality of life for the individual. He also had sympathy for female suffrage and (later in life) for labor co-operatives.

One of Mill's most important contributions was his utilitarian justification of liberalism. Mill grounded liberal ideas in the instrumental and pragmatic, allowing the unification of subjective ideas of liberty gained from the French thinkers in the tradition of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the more rights-based philosophies of John Locke in the British tradition.

A third school of thought is based on the social contract theory. According to this view, agents negotiating about the form of society would create a liberal society. There are several variants of this theory, some of them reaching contradiciting conclusions. Famous proponents of this theory that have at least certain liberal elements include Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John Locke and Immanuel Kant. In modern times, proponents include John Rawls, Robert Nozick, David Gauthier and Jan Narveson.

Democracy

The relationship between liberalism and democracy may be summed up by Winston Churchill's famous remark, "...democracy is the worst form of Government except all those other forms..." In short, there is nothing about democracy per se that guarantees freedom rather than a tyranny of the masses. The coinage liberal democracy suggests a more harmonious marriage between the two principles than actually exists. Liberals strive after the replacement of absolutism by limited government: government by consent. The idea of consent suggests democracy. At the same time, the founders of the first liberal democracies feared both government power and mob rule, and so they built into the constitutions of liberal democracies both checks and balances intended to limit the power of government by dividing those powers among several branches, and a bill of rights intended to protect the rights of individuals. For liberals, democracy is not an end in itself, but an essential means to secure liberty, individuality and diversity.

Radicalism

Further information: Radicalism (historical)In various countries in Europe and Latin-America, in the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, a radical tendency arose next to or as a successor to traditional liberalism. In the United Kingdom the Radicals united with traditionally liberal Whigs to form the Liberal Party. In other countries, including Switzerland, Germany, Bulgaria, Denmark, Spain and the Netherlands, these left-wing liberals formed their own radical parties with various names. Similar events occurred in Argentina and Chile. In French political literature it is normal to make clear separation between liberalism and radicalism. In Serbia liberalism and radicalism have and have had almost nothing in common. But even the French radicals were aligned to the international liberal movement in the first half of the twentieth century, in the Entente Internationale des Partis Radicaux et des Partis Démocratiques similaires

Positions of parties

Today the word "liberalism" is used differently in different countries. (See Liberalism worldwide.) One of the greatest contrasts is between the usage in the United States and usage in the rest of the world, most sharply in Continental Europe. In the US, liberalism is usually understood to refer to social liberalism, as contrasted with conservatism. American liberals endorse regulation for business, a limited social welfare state, and support broad racial, ethnic, sexual and religious tolerance, and thus more readily embrace Pluralism, and affirmative action. In Europe, on the other hand, liberalism is characterized by beliefs in free trade and limited government; it is not only contrasted with conservatism and Christian Democracy, but also with socialism and social democracy. In some countries, European liberals share common positions with Christian Democrats.

Before an explanation of this subject proceeds, it is important to add this disclaimer: There is always a disconnect between philosophical ideals and political realities. Also, opponents of any belief are apt to describe that belief in different terms from those used by adherents. What follows is a record of those goals that overtly appear most consistently across major liberal manifestos (e.g., the Oxford Manifesto of 1947). It is not an attempt to catalogue the idiosyncratic views of particular persons, parties, or countries, nor is it an attempt to investigate any covert goals, since both are beyond the scope of this article.

Freedom

Most political parties which identify themselves as liberal claim to promote the rights and responsibilities of the individual, free choice within an open competitive process, the free market, and the dual responsibility of the state to protect the individual citizen and guarantee their liberty. Critics of liberal parties tend to state liberal policies in different terms.

Democracy

Main article: Liberal democracyLiberalism stresses the importance of human rights, the rule of law, and representative liberal democracy as the best form of government. Elected representatives are subject to the rule of law, and their power is moderated by a constitution, which emphasizes the protection of rights and freedoms of individuals and limits the will of the majority, thereby liberalism, especially if backed up by a written constitution, becomes a necessary precursor and ultimate guarantor of democracy. Liberals are in favour of a pluralist system in which differing political and social views, even extreme or fringe views, compete for political power on a democratic basis and have the opportunity to achieve power through periodically held elections. They stress the resolution of differences by peaceful means within the bounds of democratic or lawful processes. Many liberals seek ways to increase the involvement and participation of citizens in the democratic process. Some liberals favour direct democracy instead of representative democracy.

Rule of law

The rule of law and equality before the law are fundamental to liberalism. Government authority may only be legitimately exercised in accordance with laws that are adopted through an established procedure. Another aspect of the rule of law is an insistence upon the guarantee of an independent judiciary, whose political independence is intended to act as a safeguard against arbitrary rulings in individual cases. The rule of law includes concepts such as the presumption of innocence, no double jeopardy, and Habeas Corpus. Rule of law is seen by liberals as a guard against despotism and as enforcing limitations on the power of government. In the penal system, liberals in general reject punishments they see as inhumane, including capital punishment

Civil rights

Main article: Civil rightsLiberalism advocates civil rights for all citizens: the protection and privileges of personal liberty extended to all citizens equally by law. This includes the equal treatment of all citizens irrespective of race, gender and class. Critics from an internationalist human rights school of thought argue that the civil rights advocated in the liberal view are not extended to all people, but are limited to citizens of particular states. Unequal treatment on the basis of nationality is therefore possible, especially in regard to citizenship itself.

Liberals generally believe in neutral government, in the sense that it is not for the state to determine personal values. As John Rawls put it, "The state has no right to determine a particular conception of the good life". In the United States this neutrality is expressed in the Declaration of Independence as the right to the pursuit of happiness. Both in Europe and in the United States, liberals often support the pro-choice movement and advocate equal rights for women and homosexuals.

Liberals in Europe are generally hostile to any attempts by the state to enforce equality in employment by legal action against employers, whereas in the United States many social liberals favor such affirmative action. Liberals in general support equal opportunity, but not necessarily equal outcome. Most European liberal parties do not favour employment quotas for women and ethnic minorities as the best way to end gender and racial inequality. However, all agree that arbitrary discrimination on the basis of race or gender is morally wrong.

Free market

Main articles: Economic liberalism, Capitalism, Free market, and Free tradeEconomic liberals today stress the importance of a free market and free trade, and seek to limit government intervention in both the domestic economy and foreign trade. Social liberal movements often agree in principle with the idea of free trade, but maintain some skepticism, seeing unrestricted trade as leading to the growth of multi-national corporations and the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of the few. In the post-war consensus on the welfare state in Europe, liberals supported government responsibility for health, education, and alleviating poverty while still calling for a market based on independent exchange. Liberals agree that a high quality of health care and education should be available for all citizens, but differ in their views on the degree to which governments should supply these benefits. Liberal movements seek a balance between individual responsibility and community responsibility. In particular, liberals favor special protection for the handicapped, the sick, the disabled, and the aged.

European liberalism turned back to more laissez-faire policies in the 1980s and 1990s, and supported privatisation and liberalisation in health care and other public sectors. Modern European liberals generally tend to believe in a smaller role for government. The European liberal consensus appears to involve a belief that economies should be decentralized. In general, contemporary European liberals do not believe that the government should directly control any industrial production through state owned enterprises, which places them in opposition to social democrats.

Environment

Main article: Green liberalismMany liberals share values with environmentalists, such as the Green Party. They seek to minimize the damage done by the human species on the natural world, and to maximize the regeneration of damaged areas. Some such activists attempt to make changes on an economic level by acting together with businesses, but others favor legislation in order to achieve sustainable development. Other liberals do not accept government regulation in this matter and argue that the market should regulate itself in some fashion.

International relations

Main article: Liberal international relations theoryThere is no consensus about liberal doctrine in international politics, though there are some central notions, which can be deduced from, for example, the opinions of Liberal International. Social liberals often believe that war can be abolished. Some favor internationalism, and support the United Nations. Economic liberals, on the other hand, favor non-interventionism rather than collective security. Liberals believe in the right of every individual to enjoy the essential human liberties, and support self-determination for national minorities. Essential also is the free exchange of ideas, news, goods and services between people, as well as freedom of travel within and between all countries. Liberals generally oppose censorship, protective trade barriers, and exchange regulations.

Some liberals were among the strongest advocates of international co-operation and the building of supra-national organizations, such as the European Union. In the view of social liberals, a global free and fair market can only work if companies worldwide respect a set of common minimal social and ecological standards. A controversial question, on which there is no liberal consensus, is immigration. Do nations have a right to limit the flow of immigrants from countries with growing populations to countries with stable or declining populations?

Conservative liberalism

Main article: Conservative liberalismExamples include the People's Party for Freedom and Democracy in the Netherlands, the Moderate Party (Sweden), the Liberal Party of Denmark and, in some ways, the Free Democratic Party of Germany.

Liberal conservatism

Main article: Liberal conservatismLiberal conservatism is a widespread liberal movement. Examples include the Liberal Democratic Party in Japan, Conservative Party of Canada, the Liberal Front Party (Brazil),Forza Italia, Civic Platform (Poland), and the Liberal Party of Australia.

International relations theory

Main article: Liberal international relations theory"Liberalism" in international relations is a theory that holds that state preferences, rather than state capabilities, are the primary determinant of state behavior. Unlike realism where the state is seen as a unitary actor, liberalism allows for plurality in state actions. Thus, preferences will vary from state to state, depending on factors such as culture, economic system or government type. Liberalism also holds that interaction between states is not limited to the political/security ("high politics"), but also economic/cultural ("low politics") whether through commercial firms, organizations or individuals. Thus, instead of an anarchic international system, there are plenty of opportunities for cooperation and broader notions of power, such as cultural capital (for example, the influence of a country's films leading to the popularity of its culture and the creation of a market for its exports worldwide). Another assumption is that absolute gains can be made through co-operation and interdependence – thus peace can be achieved.

Liberalism as an international relations theory is not inherently linked to liberalism as a more general domestic political ideology. Increasingly, modern liberals are integrating critical international relations theory into their foreign policy positions.

Neoliberalism

| The neutrality of this section is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (July 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Originally coined 1938 at the Colloque Walter Lippmann by the German sociologist and economist Alexander Rüstow, "neoliberalism" is a label referring to the recent reemergence of classical liberalism among political and economic scholars and policy-makers. The label is usually used by people who oppose liberalism; proponents usually describe themselves simply as "liberals".

The emerged liberalism—like classical liberalism—supports free markets, free trade, and decentralized decision-making. Higher economic freedom has been found to correlate strongly with higher living standards, self-reported happiness, and peace. Since the 1970s, most of the world's countries have become more liberal. Between 1985 and 2005, only a small amount of surveyed countries did not increase their Economic Freedom of the World score.

Neoconservatism

Main article: NeoconservatismDespite its name, Neoconservatism can be considered a liberal political philosophy that emerged in the United States of America, which supports actively using American economic and military power to bring liberalism, democracy, and human rights to other countries. Unlike traditional American conservatives, neoconservatives are generally comfortable with a minimally-bureaucratic welfare state; and, while generally supportive of free markets, they are willing to interfere for overriding social purposes. Neoconservative philosophy was originally born out of the aggressive idealism of former socialists and social liberals such as Irving Kristol. Since then, neoconservatism has arguably branched out into various forms.

Social democracy

The basic ideological difference between liberalism and social democracy lies in the role of the State in relation to the individual. Liberals value liberty, rights, freedoms, and private property as fundamental to individual happiness, and regard democracy as an instrument to maintain a society where each individual enjoys the greatest amount of liberty possible (subject to the Harm Principle). Hence, democracy and parliamentarianism are mere political systems which legitimize themselves only through the amount of liberty they promote, and are not valued per se. While the state does have an important role in ensuring positive liberty, liberals tend to trust that individuals are usually capable in deciding their own affairs, and generally do not need deliberate steering towards happiness.

Social democracy, on the other hand, has its roots in socialism (especially in democratic socialism), and typically favours a more community-based view. While social democrats also value individual liberty, they do not believe that real liberty can be achieved for the majority without transforming the nature of the state itself. Having rejected the revolutionary approach of Marxism, and choosing to further their goals through the democratic process, social democrats nevertheless retain a strong skepticism for capitalism, which they believe needs to be regulated or managed for the greater good. This focus on the greater good may, potentially, make social democrats more ready to step in and steer society in a direction that is deemed to be more equitable.

In practice, however, the differences between the two may be harder to perceive. This is especially the case nowadays, as many social democratic parties have shifted towards the center and adopted Third Way politics.

Quotations

- "The remission of debts was peculiar to Solon; it was his great means for confirming the citizens' liberty; for a mere law to give all men equal rights is but useless, if the poor must sacrifice those rights to their debts, and, in the very seats and sanctuaries of equality, the courts of justice, the offices of state, and the public discussions, be more than anywhere at the beck and bidding of the rich." Plutarch, Parallel Lives.

- "The sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant." - John Stuart Mill, "On Liberty"

- "Liberalism wagers that a state ... can be strong but constrained – strong because constrained ... Rights to education and other requirements for human development and security aim to advance equal opportunity and personal dignity and to promote a creative and productive society. To guarantee those rights, liberals have supported a wider social and economic role for the state, counterbalanced by more robust guarantees of civil liberties and a wider social system of checks and balances anchored in an independent press and pluralistic society." - Paul Starr

See also

|

Notes

- Free Trade and Liberal England, 1846-1946 By Anthony Howe

- Ideologies and Political Theory By Michael Freeden

- The Cambridge Economic History of Europe by Peter Mathias, John Harold Clapham, Michael Moïssey Postan, Sidney Pollard, Edwin Ernest Rich, Eileen Edna Power, H. J. Habakkuk

- ^ Locke, John (1690). [[Two Treatises of Government]] (10th edition). Project Gutenberg. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

{{cite book}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - Paul E. Sigmund, editor, The Selected Political Writings of John Locke, Norton, 2003, ISBN 0393964515 p. iv "(Locke's thoughts) underlie many of the fundamental political ideas of American liberal constitutional democracy...", "At the time Locke wrote, his principles were accepted in theory by a few and in practice by none."

- Thomas Jefferson, Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776.

- "in promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion", The Charter of the United Nations, Chapter One,

- James L. Richardson, Contending Liberalism in World Politics: Ideology and Power,

- Solon, Where did I fail?", from The Norton Book of Classical Literature, Bernard Knox, editor, Norton, 1993.

- Livy, History of Rome From Its Foundation, Penguin Classics, 1960.

- Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 9780199540594.

- Niccolo Machiavelli, Discourses on Livy, University of Chicago Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0226500362

- Hel. M. WILLIAMS, Sk. Fr. Rep. I. xi. 113," (presumably Helen Maria Williams) Sketches of the State of Manners and Opinions in the French Republic. 1801. Cited in the Oxford English Dictionary.

- John Locke, Two Treatises of Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration, Digireads.com, 2005, ISBN 9781420924930

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau The Social Contract and Discourses, BN Publishing, 2007, ISBN 9789562915410

- Will and Ariel Durant, Rousseau and Revolution, Simon and Schuster, 1967.

- Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Bantam Classics, 2003, ISBN 9780553585971

- "Magna Carta" in Encyclopedia Britannica Online

- Sullivan, Antony T. (January–February 1997), "Istanbul Conference Traces Islamic Roots of Western Law, Society", Washington Report on Middle East Affairs: 36, retrieved 2008-02-29

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Weeramantry, Judge Christopher G. (1997), Justice Without Frontiers: Furthering Human Rights, Brill Publishers, p. 134, ISBN 9041102418

- Pauline Gregg, Free-Born John: A Biography of John Lilburne, Phoenix Press, 2001, ISBN 9781842122006

- Charles de Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws, Cambridge University Press, 1989, ISBN 9780521369749

- Richard Whatmore, Republicanism and the French Revolution: An Intellectual History of Jean-Baptiste Say's Political Economy, Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 9780199241156

- Will and Ariel Durant, Rousseau and Revolution, MJF Books, 1997, ISBN 9781567310214

- David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature, Cornell University, 2009, ISBN 9781112156120

- A. Marisson, Free Trade and Its Reception 1815-1960: Freedom and Trade, Routledge, 1998, ISBN 9780415155274

- Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Bantam Classics,2003, ISBN 9780553585971

- Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Book Jungle, 2007, ISBN 9781604244199

- Immanuel Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, 3rd ed.. Hackett, 1993, ISBN 9780872201675

- Adam Zamoyski, The Polish Way, Hippocrene Books, 1993, ISBN 9780781802000

- Mark T. Hooker, The History of Holland, Greenwood Press, 1999, ISBN 9780313306587

- ^ Pierre Manent and Rebecca Balinski, An Intellectual History of Liberalism, Princeton University Press, 1996, ISBN 9780691029115

- http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/339173/liberalism

- Marshall C. Eakin, The History of Latin America: Collision of Cultures, Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, ISBN 9781403980816

- ^ Pierre Manent, An Intellectual History of Liberalism, Princeton University Press, 1996, ISBN 9780691029115

- R.A. Leigh, Unsolved Problems in the Bibliography of J.-J. Rousseau, Cambridge, 1990, plate 22.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Rousseau: 'The Social Contract' and Other Later Political Writings, Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 9780521424462

- David Blackbourn, History of Germany, 1780-1918: The Long Nineteenth Century, Wiley-Blackwell, 2002, ISBN 9780631231967

- Christopher Duggan, A Concise History of Italy, Cambridge University Press, 1994, ISBN 9780521408486

- James Martin, Piero Gobetti and the Politics of Liberal Revolution, Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, ISBN 9780230602748

- Richard E. Ellis, The Union at Risk: Jacksonian Democracy, States' Rights, and Nullification Crisis, Oxford University Press, 1989, ISBN 9780195061871

- Bruce Catton, The Civil War, Mariner Books, 2004, ISBN 9780618001873

- "By the end of the 19th century ... the ideal of a market economy ... concentrated vast wealth in the hands of a relatively small number of industrialists and financiers ... great masses of people ... lived in poverty." "The system periodically came to a near halt in periods of stagnation that came to be called depressions." "those who owned or managed the means of production had acquired enormous economic power that they used to influence and control government ... some of the very energies that had demolished the power of despots now nourished a new despotism.", http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/339173/liberalism

- "The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims. They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social institutions." "The proletarians have nothing to loose but their chains.", Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The Communist Manifesto, Filiquarian, 2007, ISBN 9781599867526

- Archie Brown, The Rise and Fall of Communism, Ecco, 2009, ISBN 9780061138799

- David E. Ingersoll, The Philosophic Roots of Modern Ideology: Liberalism, Communism, Fascism, Prentice Hall, 1990, ISBN 9780136626442

- Maria Dimova-Cookson and William J. Mander, T. H. Green: Ethics, Metaphysics, and Political Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN: 9780199271665.

- Herbert Spencer, The Man Versus the State, Liberty Fund Inc., 1982, ISBN: 9780913966983

- Sharon L. Wolchik and Jane L. Curry, editors, Central and East European Politics: From Communism to Democracy, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, ISBN: 9780742540682

- "The spectre of regimentation in centrally planned economies and the dangers of bureaucracy even in mixed economies deterred them from jettisoning the market and substituting a putatively omnicompetent state. On the other hand — and this is a basic difference between classical and modern liberalism — most liberals came to recognize that the operation of the market needed to be supplemented and corrected."

- Robert Skidelsky, John Maynard Keynes: 1883-1946: Economist, Philosopher, Statesman, Penguin, 2005, ISBN: 9780143036159.

- "Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt to lift the United States out of the Great Depression, typified modern liberalism in its vast expansion of the scope of governmental activities and its increased regulation of business. Among the measures that New Deal legislation provided were emergency assistance and temporary jobs to the unemployed, restrictions on banking and financial industries, more power for trade unions to organize and bargain with employers, and establishment of the Social Security program."

- http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/laureates/1974/press.html

- David McCullough, John Adams, Simon & Schuster, 2008, ISBN 9781416575887

- Walter Isaacson, "Benjamin Franklin, An American Life, Simon & Schuster, 2004, ISBN 9780743258074

- L.T. Hobhouse: Liberalism, 1911.

- Gustave de Molinari: The Private Production of Security, 1849.

- Herbert Spencer: The Right to Ignore the State, 1851.

- Wilhelm von Humboldt: The Limits of State Action, 1792.

- Anthony Alblaster: The Rise and Decline of Western Liberalism, New York, Basil Blackwell, 1984, page 353

- compare: Guide de Ruggeiro: The History of European Liberalism, Bacon press, 1954, page 379

- See for more information the Liberale und radikale Parteien in Klaus von Beyme: Parteien in westlichen Demokratien, München, 1982

- Compare page 255 and further in the Guide to the Political Parties of South America (Pelican Books, 1973

- See page 1 and further of A sense of liberty, by Julie Smith, published by the Liberal International in 1997.

- See for example Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. in 1962: Liberalism in the American usage has little in common with the word as used in the politics of any European country, save possibly Britain in Liberalism in America: A Note for Europeans from The Politics of Hope, Riverside Press, Boston. See for a similar view Jamie F. Metzl: In the same "Liberalism" as the term is used in America today is not used in the "older, European sense, but has come to mean something quite different, namely policies upholding the modern welfare state in The Rise of Illiberal Democracy by Fareed Zakaria, Foreign Affairs, November/December, 1997, Vol 76, No. 6

- The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad, Fareed Zakaria, (W.W. Norton & Company; 2003) ISBN 0-393-04764-4

- See for example the Oxford Manifesto 1997 of the Liberal International.

- Oxford Manifesto, 1947

- Liberal International > The International

- Oliver Marc Hartwich: Neoliberalism: The Genesis of a Political Swearword

- ^ Economic Freedom of the World 2005, Fraser Institute

- Polity, 2008 Robinson, Paul. Dictionary of International Security. Polity, 2008. p. 135

- Fiala, Andrew. The Just War Myth. Rowman & Littlefield. 2008. p. 133

- Vaughn, Stephen L. Encylcopedia of American Journalism. CRC Press, 2007 p. 329

- Tanner, Michael. Leviathan on the Right. Cato Institute, 2007. pp 33-34.

- See, for example, "The overlap between social democracy and social liberalism".

- Plutarch, Plutarch's Lives, Modern Library, 2001, ISBN 9780375756764

- John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, Longman, 2006, ISBN 9780321276148

- The New Republic, March 2007

References

- Willard, Charles Arthur. Liberalism and the Problem of Knowledge: A New Rhetoric for Modern Democracy, University of Chicago Press, 1996.

- Michael Scott Christofferson "An Antitotalitarian History of the French Revolution: François Furet's Penser la Révolution française in the Intellectual Politics of the Late 1970s" (in French Historical Studies, Fall 1999)

- Piero Gobetti La Rivoluzione liberale. Saggio sulla lotta politica in Italia, Bologna, Rocca San Casciano, 1924

Further reading

Prominent law scholars

- Putting liberalism in its place / Paul W Kahn, 2005 (Yale University)

- Liberalism divided: freedom of speech and the many uses of State power / Owen M Fiss, 1996 (Yale University)

- The future of liberal revolution / Bruce A Ackerman, 1992 (Yale University)

- Social justice in the liberal state / Bruce A Ackerman, 1980 (Yale University)

- Notions of fairness versus the Pareto principle: on the role of logical consistency / Louis Kaplow, 2000 (Harvard University)

- Knowledge & politics / Roberto Mangabeira Unger., 1975 (Harvard University)

- Principles for a free society / Richard Allen Epstein, 1999 (University of Chicago)

- Fairness in a liberal society / Richard Allen Epstein, 2005 (University of Chicago)

- Skepticism and freedom: a modern case for classical liberalism / Richard Allen Epstein., 2003 (University of Chicago)

- Cultivating humanity: a classical defense of reform in liberal education / Martha Nussbaum, 1997 (University of Chicago)

- Free markets and social justice / Cass R Sunstein, 1997 (University of Chicago)

- Reasonably radical: deliberative liberalism and the politics of identity / Anthony Simon Laden, 2001 (University of Chicago)

- The new inequality: creating solutions for poor America / ed. Joshua Cohen, 1999 (Stanford University)

- The rise and fall of British liberalism, 1776-1988 / Alan Sykes, 1997 (Stanford University)

- A stream of windows: unsettling reflections on trade, immigration, and democracy / Jagdish Bhagwati, 1998 (Columbia University)

- Nature and politics: liberalism in the philosophies of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau / Andrzej Rapaczynski, 1987 (Columbia University)

- Law and liberalism in the 1980s: the Rubin lectures at Columbia University / Vincent Blasi, 1991 (Columbia University)

- Ways of war and peace: realism, liberalism, and socialism / Michael W Doyle, 1997 (Columbia University)

- The Liberal future in America: essays in renewal / ed. Michael B Levy, 1985 (University of California, Berkeley)

- Boundaries and allegiances: problems of justice and responsibility in liberal thought / Samuel Scheffler, 2001 (University of California, Berkeley)

- The anatomy of antiliberalism / Stephen Holmes, 1993 (University of New York)

- Passions and constraint: on the theory of liberal democracy / Stephen Holmes, 1995 (University of New York)

- Benjamin Constant and the making of modern liberalism / Stephen Holmes, 1984 (University of New York)

- Liberal rights: collected papers, 1981-1991 / Jeremy Waldron, 1993 (University of New York)

- Liberals and social democrats / Peter Clarke., 1978 (University of Oxford)

- Law and the community: the end of individualism? / ed. Leslie Green, 1989 (University of Oxford)

- From promise to contract: towards a liberal theory of contract / Dori Kimel, 2003 (University of Oxford)

- The new enlightenment: the rebirth of liberalism / ed. Peter Clarke, 1986 (University of Oxford)

- Constitutional justice: a liberal theory of the rule of law / T.R.S Allan, 2001 (University of Cambridge)

Prominent philosophers

- Liberalism and social action / John Dewey, 1963 (University of Chicago)

- Combat liberalism / Mao Zedong, 1954 (Peking University)

- Free thought and official propaganda / Bertrand Russell, 1922 (University of Cambridge)

- Political Liberalism / John Rawls, 2005 (Harvard University)

- Lectures on the history of political philosophy / John Rawls, 2007 (Harvard University)

- The law of peoples; with, The idea of public reason revisited / John Rawls., 1999 (Harvard University)

- Conditions of liberty: civil society and its rivals / Ernest Gellner, 1994 (University of Cambridge)

- Liberty: incorporating four essays on liberty / Isaiah Berlin., 2002 (University of Oxford)

- Objectivity and liberal scholarship / Noam Chomsky, 2003 (Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

- Profit over people: neoliberalism and global order / Noam Chomsky, 1999 (Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

- Democracy in a neoliberal order: doctrines and reality / Noam Chomsky, 1997 (Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

- Liberal politics and the public sphere / Charles Taylor, 1995 (McGill University)

- Beyond liberalization: social opportunity and human capability / Amartya Kumar Sen., 1994 (Harvard University)

- Sovereign virtue: the theory and practice of equality / Ronald Dworkin, 2000 (University of New York))

- The legacy of Isaiah Berlin / ed. Ronald Dworkin., 2001 (University of New York)

- Concealment and exposure: and other essays / Thomas Nagel, 2002 (University of New York)

- Liberals and communitarians / Stephen Mulhall., 1992 (University of Oxford)

- John Dewey and the High Tide of American Liberalism / Alan Ryan, 1995 (University of Oxford)

- Liberal reform in an illiberal regime: the creation of private property in Russia / Stephen Williams, 2006 (University of Oxford)

- Liberalism, religion, and the sources of value / Simon Blackburn, 2005 (University of Cambridge)

- Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth-Century America / Richard Rorty, 1999 (Stanford University)

- Bridging Liberalism and Multiculturalism in American Education / Bob Reich, 2002 (Stanford University)

- Boundaries and allegiances: problems of justice and responsibility in liberal thought / Samuel Scheffler, 2001 (University of California, Berkeley)