| Revision as of 02:43, 8 June 2010 view sourceAndrew c (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users31,890 edits Undid rv:Nutriveg (talk) MastCell was editing in good faith. no reason to outright remove those changes. try building on them.. OWN issue?← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:48, 8 June 2010 view source Nutriveg (talk | contribs)3,676 edits This is a MAJOR change, yourself agreed to change to a earlier version before. Undid revision 366707119 by Andrew c (talk)Next edit → | ||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

| ==Health risks== | ==Health risks== | ||

| Abortion, when legally performed in the ] |

Abortion, when legally performed in the ] is among the safest procedures in medicine.<ref name="lancet-grimes">{{cite journal |author=Grimes DA, Benson J, Singh S, ''et al.'' |title=Unsafe abortion: the preventable pandemic |journal=Lancet |volume=368 |issue=9550 |pages=1908–19 |year=2006 |month=November |pmid=17126724 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69481-6 |url=http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/general/lancet_4.pdf}}</ref><ref name="grimes-overview">{{cite journal |author=Grimes DA, Creinin MD |title=Induced abortion: an overview for internists |journal=Ann. Intern. Med. |volume=140 |issue=8 |pages=620–6 |year=2004 |month=April |pmid=15096333 |doi= |url=http://www.annals.org/content/140/8/620.full}}</ref> In those cases ] is rare; in the US, for example, it's below 1 per 100,000 abortion procedures.<ref name="grimes-mortality">{{cite journal |author=Grimes DA |title=Estimation of pregnancy-related mortality risk by pregnancy outcome, United States, 1991 to 1999 |journal=Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. |volume=194 |issue=1 |pages=92–4 |year=2006 |month=January |pmid=16389015 |doi=10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.070 |url=}}</ref> However ], which is defined by the ] as those abortions performed by unskilled individuals, with hazardous equipment, or in unsanitary facilities carries a high risk of maternal death and other complications.<ref name="who-unsafe-1995">{{cite web| publisher = ] | title = The Prevention and Management of Unsafe Abortion | date = April 1995 | accessdate = June 1, 2010 | url = http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1992/WHO_MSM_92.5.pdf |format = ]}}</ref> ''See also the section below on ] and the article ].'' | ||

| ====Surgical abortion==== | |||

| The complication rate after surgical abortion is low. Complications can include ], ], and retained products of conception requiring a second procedure to evacuate.<ref name="arch-fam-practice">{{cite journal |author=Westfall JM, Sophocles A, Burggraf H, Ellis S |title=Manual vacuum aspiration for first-trimester abortion |journal=Arch Fam Med |volume=7 |issue=6 |pages=559–62 |year=1998 |pmid=9821831 |doi= |url=http://archfami.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/7/6/559}}</ref> Complications after second-trimester abortion are similar to those after first-trimester abortion, and depend somewhat on the method chosen. A 2008 ] review found that ] was safer than other means of second-trimester abortion.<ref name="cochrane-2nd-tri">{{cite journal |author=Lohr PA, Hayes JL, Gemzell-Danielsson K |title=Surgical versus medical methods for second trimester induced abortion |journal=Cochrane Database Syst Rev |volume= |issue=1 |pages=CD006714 |year=2008 |pmid=18254113 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD006714.pub2 |url=http://mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD006714/frame.html}}</ref> The risk of major complications is highest after 20 weeks of gestation, and lowest before the 8th week.<ref name="Pregler">{{cite book|last1=Pregler|first1=Janet P.|last2=DeCherney|first2=Alan H. |title=Women's health: principles and clinical practice|year=2002|publisher=pmph usa|isbn=978-1550091700|page=232}}</ref> ] increases the risk of uterine rupture, as it relaxes uterine musculature making it easier to perforate.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Morgan|first1=Mark|last2=Siddighi|first2=Sam|title=NMS Obstetrics and Gynecology|edition=5|series=National Medical Series for Independent Study|year=2004|publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins|isbn=978-0781726795|page=140}}</ref> | |||

| Surgical abortion methods, like most ]s, carry a small potential for serious complications.<ref>{{cite book |author=] |title=Medical Methods for Termination of Pregnancy: Report of a Who Scientific Group |series=Who Technical Report Series No. 871 |publisher=] |location=] |year=1997 |pages= |isbn=92-4-120871-6 |oclc=38276325}}{{pn}}</ref> | |||

| Incidence of major complications is proportionally low and varies depending on how far ] has progressed and the surgical method used.<ref name="Pregler"/> Concerning gestational age, incidence of major complications is highest after 20 weeks of gestation and lower before the 8th week.<ref name="Pregler"/> With more advanced gestation there is a higher risk of ] and retained products of conception.<ref name="Rello">{{cite book|editor=Jordi Rello|title=Infectious diseases in critical care|edition=2|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-3540344056|page=490}}</ref> | |||

| Concerning the methods used, general incidence of major complications varies from lower for suction curettage, to higher for saline instillation.<ref name="Pregler">{{cite book|last1=Pregler|first1=Janet P.|last2=DeCherney|first2=Alan H. |title=Women's health: principles and clinical practice|year=2002|publisher=pmph usa|isbn=978-1550091700|page=232}}</ref> Possible complications include ], incomplete abortion, uterine or pelvic infection, ongoing intrauterine pregnancy, misdiagnosed/unrecognized ], ] (in the uterus), ] and cervical laceration.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Botha|first1=Rosanne L.|last2=Bednarek|first2=Paula H.|last3=Kaunitz|first3=Andrew M.|coauthors=Alison B. Edelman|editor=Guy I Benrubi |title=Handbook of Obstetric and Gynecologic Emergencies|edition=4|year=2010|publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins|isbn=978-1605476667|page=258|chapter=Complications of Medical and Surgical Abortion}}</ref> Use of ] increases the risk of complications because it relaxes uterine musculature making it easier to perforate.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Morgan|first1=Mark|last2=Siddighi|first2=Sam|title=NMS Obstetrics and Gynecology|edition=5|series=National Medical Series for Independent Study|year=2004|publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins|isbn=978-0781726795|page=140}}</ref> | |||

| Surgical abortion increases incidence of both ] and morbid ] by a factor of 1.8.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Studd|first1=John|last2=Seang |first2=Lin Tan|last3=Chervenak|first3=Frank A.|title=Progress in Obstetrics and Gynaecology|volume=17|year=2007|isbn=978-0443103131|page=206}}</ref> | |||

| <!-- pain should be better defined to avoid ignoring a possible complication | |||

| Women typically experience minor pain during first-trimester abortion procedures. In a 1979 study of 2,299 patients, 97% reported experiencing some degree of pain. Patients rated the pain as being less than earache or toothache, but more than headache or backache.<ref name="pmid443287">{{cite journal |author=Smith GM, Stubblefield PG, Chirchirillo L, McCarthy MJ |title=Pain of first-trimester abortion: its quantification and relations with other variables |journal=Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. |volume=133 |issue=5 |pages=489–498 |year=1979 |pmid=443287 |doi= |url=}}</ref>{{better source}}--> | |||

| ====Medical abortion==== | |||

| {{Main|Medical abortion#Health risks}} | |||

| In the first trimester, medical abortion is generally considered as safe as surgical abortion.<ref name="who-medical-abortion">{{cite web | publisher = ] | title = Medical versus surgical methods for first trimester termination of pregnancy | url = http://apps.who.int/rhl/fertility/abortion/pccom/en/index.html | date = December 15, 2006 | accessdate = June 1, 2010}}</ref> | |||

| ] is generally considered as safe as surgical abortion in the first trimester, but is associated with more pain and a lower success rate.<ref name="who-medical-abortion">{{cite web | publisher = ] | title = Medical versus surgical methods for first trimester termination of pregnancy | url = http://apps.who.int/rhl/fertility/abortion/pccom/en/index.html | date = December 15, 2006 | accessdate = June 1, 2010}}</ref> Overall, the risk of ] is lower with medical than with surgical abortion,<ref name="nejm-mifepristone">{{cite journal |author=Spitz IM, Bardin CW, Benton L, Robbins A |title=Early pregnancy termination with mifepristone and misoprostol in the United States |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=338 |issue=18 |pages=1241–7 |year=1998 |month=April |pmid=9562577 |doi= |url=}}</ref> although in 2005 four deaths after medical abortion were reported due to infection with '']''.<ref name="c-sordellii">{{cite journal |author=Fischer M, Bhatnagar J, Guarner J, ''et al.'' |title=Fatal toxic shock syndrome associated with Clostridium sordellii after medical abortion |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=353 |issue=22 |pages=2352–60 |year=2005 |month=December |pmid=16319384 |doi=10.1056/NEJMoa051620 |url=}}</ref> As a result, some abortion providers have begun using preventive antibiotics with medical abortion to reduce this risk.<ref name="nejm-pp">{{cite journal |author=Fjerstad M, Trussell J, Sivin I, Lichtenberg ES, Cullins V |title=Rates of serious infection after changes in regimens for medical abortion |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=361 |issue=2 |pages=145–51 |year=2009 |month=July |pmid=19587339 |doi=10.1056/NEJMoa0809146 |url=}}</ref> | |||

| ===Mental health=== | ===Mental health=== | ||

Revision as of 02:48, 8 June 2010

Medical condition

| Abortion | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Obstetrics |

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by the removal or expulsion from the uterus of a fetus or embryo, resulting in or caused by its death. An abortion can occur spontaneously due to complications during pregnancy or can be induced, in humans and other species. In the context of human pregnancies, an abortion induced to preserve the health of the gravida (pregnant female) is termed a therapeutic abortion, while an abortion induced for any other reason is termed an elective abortion. The term abortion most commonly refers to the induced abortion of a human pregnancy, while spontaneous abortions are usually termed miscarriages.

Abortion has a long history and has been induced by various methods including herbal abortifacients, the use of sharpened tools, physical trauma, and other traditional methods. Contemporary medicine utilizes medications and surgical procedures to induce abortion. The legality, prevalence, and cultural views on abortion vary substantially around the world. In many parts of the world there is prominent and divisive public controversy over the ethical and legal issues of abortion. Abortion and abortion-related issues feature prominently in the national politics in many nations, often involving the opposing pro-life and pro-choice worldwide social movements. Incidence of abortion has declined worldwide, as access to family planning education and contraceptive services has increased. Abortion incidence in the United States declined 8% from 1996 to 2003.

Types

Spontaneous abortion

Main article: Miscarriage

Spontaneous abortion (also known as miscarriage) is the expulsion of an embryo or fetus due to accidental trauma or natural causes before approximately the 22nd week of gestation; the definition by gestational age varies by country. Most miscarriages are due to incorrect replication of chromosomes; they can also be caused by environmental factors. A pregnancy that ends before 37 weeks of gestation resulting in a live-born infant is known as a "premature birth". When a fetus dies in utero after about 22 weeks, or during delivery, it is usually termed "stillborn". Premature births and stillbirths are generally not considered to be miscarriages although usage of these terms can sometimes overlap.

Between 10% and 50% of pregnancies end in clinically apparent miscarriage, depending upon the age and health of the pregnant woman. Most miscarriages occur very early in pregnancy, in most cases, they occur so early in the pregnancy that the woman is not even aware that she was pregnant. One study testing hormones for ovulation and pregnancy found that 61.9% of conceptuses were lost prior to 12 weeks, and 91.7% of these losses occurred subclinically, without the knowledge of the once pregnant woman.

The risk of spontaneous abortion decreases sharply after the 10th week from the last menstrual period (LMP). One study of 232 pregnant women showed "virtually complete by the end of the embryonic period" (10 weeks LMP) with a pregnancy loss rate of only 2 percent after 8.5 weeks LMP.

The most common cause of spontaneous abortion during the first trimester is chromosomal abnormalities of the embryo/fetus, accounting for at least 50% of sampled early pregnancy losses. Other causes include vascular disease (such as lupus), diabetes, other hormonal problems, infection, and abnormalities of the uterus. Advancing maternal age and a patient history of previous spontaneous abortions are the two leading factors associated with a greater risk of spontaneous abortion. A spontaneous abortion can also be caused by accidental trauma; intentional trauma or stress to cause miscarriage is considered induced abortion or feticide.

Induced abortion

A pregnancy can be intentionally aborted in many ways. The manner selected depends chiefly upon the gestational age of the embryo or fetus, which increases in size as it ages. Specific procedures may also be selected due to legality, regional availability, and doctor-patient preference. Reasons for procuring induced abortions are typically characterized as either therapeutic or elective. An abortion is medically referred to as therapeutic when it is performed to:

- save the life of the pregnant woman;

- preserve the woman's physical or mental health;

- terminate pregnancy that would result in a child born with a congenital disorder that would be fatal or associated with significant morbidity; or

- selectively reduce the number of fetuses to lessen health risks associated with multiple pregnancy.

An abortion is referred to as elective when it is performed at the request of the woman "for reasons other than maternal health or fetal disease."

Methods

Medical

Main article: Medical abortion"Medical abortions" are non-surgical abortions that use pharmaceutical drugs, and are only effective in the first trimester of pregnancy. Medical abortions comprise 10% of all abortions in the United States and Europe. Combined regimens include methotrexate or mifepristone, followed by a prostaglandin (either misoprostol or gemeprost: misoprostol is used in the U.S.; gemeprost is used in the UK and Sweden.) When used within 49 days gestation, approximately 92% of women undergoing medical abortion with a combined regimen completed it without surgical intervention. Misoprostol can be used alone, but has a lower efficacy rate than combined regimens. In cases of failure of medical abortion, vacuum or manual aspiration is used to complete the abortion surgically.

Surgical

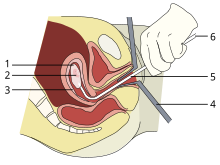

1: Amniotic sac

2: Embryo

3: Uterine lining

4: Speculum

5: Vacurette

6: Attached to a suction pump

In the first 12 weeks, suction-aspiration or vacuum abortion is the most common method. Manual Vacuum aspiration (MVA) abortion consists of removing the fetus or embryo, placenta and membranes by suction using a manual syringe, while electric vacuum aspiration (EVA) abortion uses an electric pump. These techniques are comparable, and differ in the mechanism used to apply suction, how early in pregnancy they can be used, and whether cervical dilation is necessary. MVA, also known as "mini-suction" and "menstrual extraction", can be used in very early pregnancy, and does not require cervical dilation. Surgical techniques are sometimes referred to as 'Suction (or surgical) Termination Of Pregnancy' (STOP). From the 15th week until approximately the 26th, dilation and evacuation (D&E) is used. D&E consists of opening the cervix of the uterus and emptying it using surgical instruments and suction.

Dilation and curettage (D&C), the second most common method of abortion, is a standard gynecological procedure performed for a variety of reasons, including examination of the uterine lining for possible malignancy, investigation of abnormal bleeding, and abortion. Curettage refers to cleaning the walls of the uterus with a curette. The World Health Organization recommends this procedure, also called sharp curettage, only when MVA is unavailable. The term D and C, or sometimes suction curette, is used as a euphemism for the first trimester abortion procedure, whichever the method used.

Other techniques must be used to induce abortion in the second trimester. Premature delivery can be induced with prostaglandin; this can be coupled with injecting the amniotic fluid with hypertonic solutions containing saline or urea. After the 16th week of gestation, abortions can be induced by intact dilation and extraction (IDX) (also called intrauterine cranial decompression), which requires surgical decompression of the fetus's head before evacuation. IDX is sometimes called "partial-birth abortion," which has been federally banned in the United States. A hysterotomy abortion is a procedure similar to a caesarean section and is performed under general anesthesia. It requires a smaller incision than a caesarean section and is used during later stages of pregnancy.

From the 20th to 23rd week of gestation, an injection to stop the fetal heart can be used as the first phase of the surgical abortion procedure to ensure that the fetus is not born alive.

Other methods

Historically, a number of herbs reputed to possess abortifacient properties have been used in folk medicine: tansy, pennyroyal, black cohosh, and the now-extinct silphium (see history of abortion). The use of herbs in such a manner can cause serious—even lethal—side effects, such as multiple organ failure, and is not recommended by physicians.

Abortion is sometimes attempted by causing trauma to the abdomen. The degree of force, if severe, can cause serious internal injuries without necessarily succeeding in inducing miscarriage. Both accidental and deliberate abortions of this kind can be subject to criminal liability in many countries. In Southeast Asia, there is an ancient tradition of attempting abortion through forceful abdominal massage. One of the bas reliefs decorating the temple of Angkor Wat in Cambodia depicts a demon performing such an abortion upon a woman who has been sent to the underworld.

Reported methods of unsafe, self-induced abortion include misuse of misoprostol, and insertion of non-surgical implements such as knitting needles and clothes hangers into the uterus. These methods are rarely seen in developed countries where surgical abortion is legal and available.

Health risks

Abortion, when legally performed in the developed countries is among the safest procedures in medicine. In those cases maternal death is rare; in the US, for example, it's below 1 per 100,000 abortion procedures. However unsafe abortion, which is defined by the World Health Organization as those abortions performed by unskilled individuals, with hazardous equipment, or in unsanitary facilities carries a high risk of maternal death and other complications. See also the section below on #unsafe abortion and the article Unsafe abortion#Health risks.

Surgical abortion

Surgical abortion methods, like most minimally invasive procedures, carry a small potential for serious complications.

Incidence of major complications is proportionally low and varies depending on how far pregnancy has progressed and the surgical method used. Concerning gestational age, incidence of major complications is highest after 20 weeks of gestation and lower before the 8th week. With more advanced gestation there is a higher risk of uterine perforation and retained products of conception.

Concerning the methods used, general incidence of major complications varies from lower for suction curettage, to higher for saline instillation. Possible complications include hemorrhage, incomplete abortion, uterine or pelvic infection, ongoing intrauterine pregnancy, misdiagnosed/unrecognized ectopic pregnancy, hematometra (in the uterus), uterine perforation and cervical laceration. Use of general anesthesia increases the risk of complications because it relaxes uterine musculature making it easier to perforate.

Surgical abortion increases incidence of both placenta previa and morbid adherent placentation by a factor of 1.8.

Medical abortion

Main article: Medical abortion § Health risksIn the first trimester, medical abortion is generally considered as safe as surgical abortion.

Mental health

Main article: Abortion and mental healthNo scientific research has demonstrated that abortion is a cause of poor mental health in the general population. However there are groups of women who may be at higher risk of coping with problems and distress following abortion. Some factors in a woman's life, such as emotional attachment to the pregnancy, lack of social support, pre-existing psychiatric illness, and conservative views on abortion increase the likelihood of experiencing negative feelings after an abortion. The American Psychological Association (APA) concluded that abortion does not lead to increased mental health problems.

Some proposed negative psychological effects of abortion have been referred to by anti-abortion advocates as a separate condition called "post-abortion syndrome." However, the existence of "post-abortion syndrome" is not recognized by any medical or psychological organization.

Incidence

The incidence and reasons for induced abortion vary regionally. It has been estimated that in 1995 approximately 46 million abortions were performed worldwide. Of these, 26 million are said to have occurred in places where abortion is legal; the other 20 million happened where the procedure is illegal. Some countries, such as Belgium (11.2 per 100 known pregnancies) and the Netherlands (10.6 per 100), had a comparatively low rate of induced abortion, while others like Russia (62.6 per 100) and Vietnam (43.7 per 100) had a high rate. The world ratio was 26 induced abortions per 100 known pregnancies (excluding miscarriages and stillbirths).

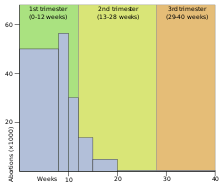

By gestational age and method

Abortion rates also vary depending on the stage of pregnancy and the method practiced. In 2003, from data collected in those areas of the United States that sufficiently reported gestational age, it was found that 88.2% of abortions were conducted at or prior to 12 weeks, 10.4% from 13 to 20 weeks, and 1.4% at or after 21 weeks. 90.9% of these were classified as having been done by "curettage" (suction-aspiration, Dilation and curettage, Dilation and evacuation), 7.7% by "medical" means (mifepristone), 0.4% by "intrauterine instillation" (saline or prostaglandin), and 1.0% by "other" (including hysterotomy and hysterectomy). The Guttmacher Institute estimated there were 2,200 intact dilation and extraction procedures in the U.S. during 2000; this accounts for 0.17% of the total number of abortions performed that year. Similarly, in England and Wales in 2006, 89% of terminations occurred at or under 12 weeks, 9% between 13 to 19 weeks, and 1.5% at or over 20 weeks. 64% of those reported were by vacuum aspiration, 6% by D&E, and 30% were medical. Later abortions are more common in China, India, and other developing countries than in developed countries.

By personal and social factors

A 1998 aggregated study, from 27 countries, on the reasons women seek to terminate their pregnancies concluded that common factors cited to have influenced the abortion decision were: desire to delay or end childbearing, concern over the interruption of work or education, issues of financial or relationship stability, and perceived immaturity. A 2004 study in which American women at clinics answered a questionnaire yielded similar results. In Finland and the United States, concern for the health risks posed by pregnancy in individual cases was not a factor commonly given; however, in Bangladesh, India, and Kenya health concerns were cited by women more frequently as reasons for having an abortion. 1% of women in the 2004 survey-based U.S. study became pregnant as a result of rape and 0.5% as a result of incest. Another American study in 2002 concluded that 54% of women who had an abortion were using a form of contraception at the time of becoming pregnant while 46% were not. Inconsistent use was reported by 49% of those using condoms and 76% of those using the combined oral contraceptive pill; 42% of those using condoms reported failure through slipping or breakage. The Guttmacher Institute estimated that "most abortions in the United States are obtained by minority women" because minority women "have much higher rates of unintended pregnancy."

Some abortions are undergone as the result of societal pressures. These might include the stigmatization of disabled persons, preference for children of a specific sex, disapproval of single motherhood, insufficient economic support for families, lack of access to or rejection of contraceptive methods, or efforts toward population control (such as China's one-child policy). These factors can sometimes result in compulsory abortion or sex-selective abortion.

History

Induced abortion can be traced to ancient times. There is evidence to suggest that, historically, pregnancies were terminated through a number of methods, including the administration of abortifacient herbs, the use of sharpened implements, the application of abdominal pressure, and other techniques.

The Hippocratic Oath, the chief statement of medical ethics for Hippocratic physicians in Ancient Greece, forbade doctors from helping to procure an abortion by pessary. Soranus, a second-century Greek physician, suggested in his work Gynaecology that women wishing to abort their pregnancies should engage in energetic exercise, energetic jumping, carrying heavy objects, and riding animals. He also prescribed a number of recipes for herbal baths, pessaries, and bloodletting, but advised against the use of sharp instruments to induce miscarriage due to the risk of organ perforation. It is also believed that, in addition to using it as a contraceptive, the ancient Greeks relied upon silphium as an abortifacient. Such folk remedies, however, varied in effectiveness and were not without risk. Tansy and pennyroyal, for example, are two poisonous herbs with serious side effects that have at times been used to terminate pregnancy.

During the medieval period, physicians in the Islamic world documented detailed and extensive lists of birth control practices, including the use of abortifacients, commenting on their effectiveness and prevalence. They listed many different birth control substances in their medical encyclopedias, such as Avicenna listing 20 in The Canon of Medicine (1025) and Muhammad ibn Zakariya ar-Razi listing 176 in his Hawi (10th century). This was unparalleled in European medicine until the 19th century.

During the Middle Ages, abortion was tolerated and there were no laws against it. A medieval female physician, Trotula of Salerno, administered a number of remedies for the “retention of menstrua,” which was sometimes a code for early abortifacients. Pope Sixtus V (1585–1590) is noted as the first Pope to declare that abortion is homicide regardless of the stage of pregnancy. Abortion in the 19th century continued, despite bans in both the United Kingdom and the United States, as the disguised, but nonetheless open, advertisement of services in the Victorian era suggests.

In the 20th century the Soviet Union (1919), Iceland (1935) and Sweden (1938) were among the first countries to legalize certain or all forms of abortion. In 1935 Nazi Germany, a law was passed permitting abortions for those deemed "hereditarily ill," while women considered of German stock were specifically prohibited from having abortions.

Society and culture

Sex-selective abortion

Main article: Sex-selective abortionSonography and amniocentesis allow parents to determine sex before birth. The development of this technology has led to sex-selective abortion, or the targeted termination of female fetuses.

It is suggested that sex-selective abortion might be partially responsible for the noticeable disparities between the birth rates of male and female children in some places. The preference for male children is reported in many areas of Asia, and abortion used to limit female births has been reported in Mainland China, Taiwan, South Korea, and India.

In India, the economic role of men, the costs associated with dowries, and a common Indian tradition which dictates that funeral rites must be performed by a male relative have led to a cultural preference for sons. The widespread availability of diagnostic testing, during the 1970s and '80s, led to advertisements for services which read, "Invest 500 rupees [for a sex test] now, save 50,000 rupees [for a dowry] later." In 1991, the male-to-female sex ratio in India was skewed from its biological norm of 105 to 100, to an average of 108 to 100. Researchers have asserted that between 1985 and 2005 as many as 10 million female fetuses may have been selectively aborted. The Indian government passed an official ban of pre-natal sex screening in 1994 and moved to pass a complete ban of sex-selective abortion in 2002.

In the People's Republic of China, there is also a historic son preference. The implementation of the one-child policy in 1979, in response to population concerns, led to an increased disparity in the sex ratio as parents attempted to circumvent the law through sex-selective abortion or the abandonment of unwanted daughters. Sex-selective abortion might be an influence on the shift from the baseline male-to-female birth rate to an elevated national rate of 117:100 reported in 2002. The trend was more pronounced in rural regions: as high as 130:100 in Guangdong and 135:100 in Hainan. A ban upon the practice of sex-selective abortion was enacted in 2003.

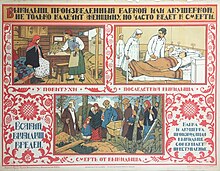

Unsafe abortion

Women seeking to terminate their pregnancies sometimes resort to unsafe methods, particularly where and when access to legal abortion is being barred.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines an unsafe abortion as being "a procedure ... carried out by persons lacking the necessary skills or in an environment that does not conform to minimal medical standards, or both." Unsafe abortions are sometimes known colloquially as "back-alley" abortions. They may be performed by the woman herself, another person without medical training, or a professional health provider operating in sub-standard conditions. Unsafe abortion remains a public health concern today due to the higher incidence and severity of its associated complications, such as incomplete abortion, sepsis, hemorrhage, and damage to internal organs. WHO estimates that 19 million unsafe abortions occur around the world annually and that 68,000 of these result in the woman's death. Complications of unsafe abortion are said to account, globally, for approximately 13% of all maternal mortalities, with regional estimates including 12% in Asia, 25% in Latin America, and 13% in sub-Saharan Africa. A 2007 study published in The Lancet found that, although the global rate of abortion declined from 45.6 million in 1995 to 41.6 million in 2003, unsafe procedures still accounted for 48% of all abortions performed in 2003. Health education, access to family planning, and improvements in health care during and after abortion have been proposed to address this phenomenon.

Abortion debate

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In the history of abortion, induced abortion has been the source of considerable debate, controversy, and activism. An individual's position on the complex ethical, moral, philosophical, biological, and legal issues is often related to his or her value system. The main positions are one that argues in favor of access to abortion and one argues against access to abortion. Opinions of abortion may be described as being a combination of beliefs on its morality, and beliefs on the responsibility, ethical scope, and proper extent of governmental authorities in public policy. Religious ethics also has an influence upon both personal opinion and the greater debate over abortion (see religion and abortion).

Abortion debates, especially pertaining to abortion laws, are often spearheaded by groups advocating one of these two positions. In the United States, those in favor of greater legal restrictions on, or even complete prohibition of abortion, most often describe themselves as pro-life while those against legal restrictions on abortion describe themselves as pro-choice. Generally, the former position argues that a human fetus is a human being with a right to live making abortion tantamount to murder. The latter position argues that a woman has certain reproductive rights, especially the choice whether or not to carry a pregnancy to term.

In both public and private debate, arguments presented in favor of or against abortion access focus on either the moral permissibility of an induced abortion, or justification of laws permitting or restricting abortion.

Debate also focuses on whether the pregnant woman should have to notify and/or have the consent of others in distinct cases: a minor, her parents; a legally married or common-law wife, her husband; or a pregnant woman, the biological father. In a 2003 Gallup poll in the United States, 79% of male and 67% of female respondents were in favor of legalized mandatory spousal notification; overall support was 72% with 26% opposed.

Public opinion

Main article: Societal attitudes towards abortionA number of opinion polls around the world have explored public opinion regarding the issue of abortion. Results have varied from poll to poll, country to country, and region to region, while varying with regard to different aspects of the issue.

A May 2005 survey examined attitudes toward abortion in 10 European countries, asking respondents whether they agreed with the statement, "If a woman doesn't want children, she should be allowed to have an abortion". The highest level of approval was 81% (in the Czech Republic); the lowest was 47% (in Poland).

In North America, a December 2001 poll surveyed Canadian opinion on abortion, asking Canadians in what circumstances they believe abortion should be permitted; 32% responded that they believe abortion should be legal in all circumstances, 52% that it should be legal in certain circumstances, and 14% that it should be legal in no circumstances. A similar poll in April 2009 surveyed people in the United States about U.S. opinion on abortion; 18% said that abortion should be "legal in all cases", 28% said that abortion should be "legal in most cases", 28% said abortion should be "illegal in most cases" and 16% said abortion should be "illegal in all cases". A November 2005 poll in Mexico found that 73.4% think abortion should not be legalized while 11.2% think it should.

Of attitudes in South America, a December 2003 survey found that 30% of Argentines thought that abortion in Argentina should be allowed "regardless of situation", 47% that it should be allowed "under some circumstances", and 23% that it should not be allowed "regardless of situation". A March 2007 poll regarding the abortion law in Brazil found that 65% of Brazilians believe that it "should not be modified", 16% that it should be expanded "to allow abortion in other cases", 10% that abortion should be "decriminalized", and 5% were "not sure". A July 2005 poll in Colombia found that 65.6% said they thought that abortion should remain illegal, 26.9% that it should be made legal, and 7.5% that they were unsure.

Breast cancer hypothesis

Main article: Abortion-breast cancer hypothesisThe abortion-breast cancer hypothesis posits that induced abortion increases the risk of developing breast cancer. This position contrasts with the scientific consensus that abortion does not cause breast cancer.

In early pregnancy, levels of estrogen increase, leading to breast growth in preparation for lactation. The hypothesis proposes that if this process is interrupted by an abortion – before full maturity in the third trimester – then more relatively vulnerable immature cells could be left than there were prior to the pregnancy, resulting in a greater potential risk of breast cancer. The hypothesis mechanism was first proposed and explored in rat studies conducted in the 1980s.

Fetal pain debate

Main article: Fetal painFetal pain, its existence, and its implications are part of a larger debate about abortion. Many researchers in the area of fetal development believe that a fetus is unlikely to feel pain until after the sixth month of pregnancy. Others disagree. Developmental neurobiologists suspect that the establishment of thalamocortical connections (at about 26 weeks) may be critical to fetal perception of pain. However, legislation has been proposed by anti-abortion advocates requiring abortion providers to tell a woman that the fetus may feel pain during an abortion procedure.

A review by researchers from the University of California, San Francisco in JAMA concluded that data from dozens of medical reports and studies indicate that fetuses are unlikely to feel pain until the third trimester of pregnancy. However a number of medical critics have since disputed these conclusions. Other researchers such as Anand and Fisk have challenged the idea that pain cannot be felt before 26 weeks, positing that pain can be felt around 20 weeks. Because pain can involve sensory, emotional and cognitive factors, it may be "impossible to know" when painful experiences are perceived, even if it is known when thalamocortical connections are established. According to opponents of fetal anesthesia, abortion clinics lack the equipment and expertise to supply such anesthesia.

Effect upon crime rate

Main article: Legalized abortion and crime effectA theory attempts to draw a correlation between the United States' unprecedented nationwide decline of the overall crime rate during the 1990s and the decriminalization of abortion 20 years prior.

The suggestion was brought to widespread attention by a 1999 academic paper, The Impact of Legalized Abortion on Crime, authored by the economists Steven D. Levitt and John Donohue. They attributed the drop in crime to a reduction in individuals said to have a higher statistical probability of committing crimes: unwanted children, especially those born to mothers who are African-American, impoverished, adolescent, uneducated, and single. The change coincided with what would have been the adolescence, or peak years of potential criminality, of those who had not been born as a result of Roe v. Wade and similar cases. Donohue and Levitt's study also noted that states which legalized abortion before the rest of the nation experienced the lowering crime rate pattern earlier, and those with higher abortion rates had more pronounced reductions.

Fellow economists Christopher Foote and Christopher Goetz criticized the methodology in the Donohue-Levitt study, noting a lack of accommodation for statewide yearly variations such as cocaine use, and recalculating based on incidence of crime per capita; they found no statistically significant results. Levitt and Donohue responded to this by presenting an adjusted data set which took into account these concerns and reported that the data maintained the statistical significance of their initial paper.

Such research has been criticized by some as being utilitarian, discriminatory as to race and socioeconomic class, and as promoting eugenics as a solution to crime. Levitt states in his book Freakonomics that they are neither promoting nor negating any course of action—merely reporting data as economists.

Mexico City Policy

Main article: Mexico City PolicyThe Mexico City policy, also known as the "Global Gag Rule" required any non-governmental organization receiving U.S. government funding to refrain from performing or promoting abortion services in other countries. This had a significant effect on the health policies of many nations across the globe. The Mexico City Policy was instituted under President Reagan, suspended under President Clinton, reinstated by President George W. Bush, and suspended again by President Barack Obama on January 24, 2009.

Religious views

Main article: Religion and abortionEach faith has many varying views on the moral implications of abortion with each side citing their own textual proof. Oftentimes, these views can be in direct opposition to each other.

Abortion law

Main articles: Abortion law and History of abortion law See also: Reproductive rights

Before the scientific discovery in the nineteenth century that human development begins at fertilization, English common law forbade abortions after "quickening”, that is, after “an infant is able to stir in the mother's womb.” There was also an earlier period in England when abortion was prohibited "if the foetus is already formed" but not yet quickened. Both pre- and post-quickening abortions were criminalized by Lord Ellenborough's Act in 1803. In 1861, the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the Offences against the Person Act 1861, which continued to outlaw abortion and served as a model for similar prohibitions in some other nations.

The Soviet Union, with legislation in 1920, and Iceland, with legislation in 1935, were two of the first countries to generally allow abortion. The second half of the 20th century saw the liberalization of abortion laws in other countries. The Abortion Act 1967 allowed abortion for limited reasons in the United Kingdom (except Northern Ireland). In the 1973 case, Roe v. Wade, the United States Supreme Court struck down state laws banning abortion, ruling that such laws violated an implied right to privacy in the United States Constitution. The Supreme Court of Canada, similarly, in the case of R. v. Morgentaler, discarded its criminal code regarding abortion in 1988, after ruling that such restrictions violated the security of person guaranteed to women under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Canada later struck down provincial regulations of abortion in the case of R. v. Morgentaler (1993). By contrast, abortion in Ireland was affected by the addition of an amendment to the Irish Constitution in 1983 by popular referendum, recognizing "the right to life of the unborn".

Current laws pertaining to abortion are diverse. Religious, moral, and cultural sensibilities continue to influence abortion laws throughout the world. The right to life, the right to liberty, the right to security of person, and the right to reproductive health are major issues of human rights that are sometimes used as justification for the existence or absence of laws controlling abortion. Many countries in which abortion is legal require that certain criteria be met in order for an abortion to be obtained, often, but not always, using a trimester-based system to regulate the window of legality:

- In the United States, some states impose a 24-hour waiting period before the procedure, prescribe the distribution of information on fetal development, or require that parents be contacted if their minor daughter requests an abortion.

- In the United Kingdom, as in some other countries, two doctors must first certify that an abortion is medically or socially necessary before it can be performed.

- In Canada, a similar requirement was rejected as unconstitutional in 1988.

Other countries, in which abortion is normally illegal, will allow one to be performed in the case of rape, incest, or danger to the pregnant woman's life or health.

- A few nations ban abortion entirely: Chile, El Salvador, Malta, and Nicaragua, with consequent rises in maternal death directly and indirectly due to pregnancy. However, in 2006, the Chilean government began the free distribution of emergency contraception.

- In Bangladesh, abortion is illegal, but the government has long supported a network of "menstrual regulation clinics", where menstrual extraction (manual vacuum aspiration) can be performed as menstrual hygiene.

In places where abortion is illegal or carries heavy social stigma, pregnant women may engage in medical tourism and travel to countries where they can terminate their pregnancies. Women without the means to travel can resort to providers of illegal abortions or try to do it themselves.

In the USA, about 8% of abortions are performed on women who travel from another state. However, that is driven at least partly by differing limits on abortion according to gestational age or the scarcity of doctors trained and willing to do later abortions.

In other animals

Further information: Miscarriage § In other animalsSpontaneous abortion occurs in various animals. For example, in sheep, it may be caused by crowding through doors, or being chased by dogs. In cows, abortion may be caused by contagious disease, such as Brucellosis or Campylobacter, but can often be controlled by vaccination. Additionally, many other diseases are known to increase the risk of miscarriage in humans and other animals.

Abortion may also be induced in animals, in the context of animal husbandry. For example, abortion may be induced in mares that have been mated improperly, or that have been purchased by owners who did not realize the mares were pregnant, or that are pregnant with twin foals.

Feticide can occur in horses and zebras due to male harassment of pregnant mares or forced copulation, although the frequency in the wild has been questioned. Male Gray langur monkeys may attack females following male takeover, causing miscarriage.

See also

- Abortion fund

- Anti-abortion violence

- Connolly v. DPP

- Fetal rights

- Late-term abortion

- Minors and abortion

- Paternal rights and abortion

- Population control

- Self-induced abortion

- Stem cell controversy

References

- Gynaecology for Lawyers By Trevor Dutt, Margaret P. Matthews

- Sedgh G, Henshaw SK, Singh S, Bankole A, Drescher J (2007). "Legal abortion worldwide: incidence and recent trends". Int Fam Plan Perspect. 33 (3): 106–16. doi:10.1363/ifpp.33.106.07. PMID 17938093.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization (2003). "Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth - A guide for midwives and doctors". Retrieved 2009-04-07. NB: This definition is subject to regional differences, see miscarriage.

- ^ "Q&A: Miscarriage". BBC. 2002-08-06. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

- Edmonds DK, Lindsay KS, Miller JF, Williamson E, Wood PJ (1982). "Early embryonic mortality in women". Fertil. Steril. 38 (4): 447–453. PMID 7117572.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nilsson, Lennart (1990). A child is born. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. p. 91. ISBN 0-385-40085-3. OCLC 21412111.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - Jauniaux, E. (1999). "Early pregnancy loss". In Martin J. Whittle and C. H. Rodeck (ed.). Fetal medicine: basic science and clinical practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 836. ISBN 0-443-05357-X. OCLC 42792567.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Stöppler, Melissa Conrad. "Miscarriage (Spontaneous Abortion)". MedicineNet.com. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jauniaux, E. (1999). "Early pregnancy loss". In Martin J. Whittle and C. H. Rodeck (ed.). Fetal medicine: basic science and clinical practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 837. ISBN 0-443-05357-X. OCLC 42792567.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Fetal Homicide Laws". National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

- Menikoff, Jerry. Law and Bioethics, p. 78 (Georgetown University Press 2001): "As the fetus grows in size, however, the vacuum aspiration method becomes increasingly difficult to use."

- ^ Roche, Natalie E. (2004). Therapeutic Abortion. Retrieved 2006-03-08.

- Encyclopedia Britannica, (2007), Vol 26, p. 674.

- Strauss LT, Gamble SB, Parker WY, Cook DA, Zane SB, Hamdan S (2007). "Abortion surveillance—United States, 2004". MMWR Surveill Summ. 56 (9): 1–33. PMID 18030283.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Spitz, I.M; Bardin, CW; Benton, L; Robbins, A (1998). "Early pregnancy termination with mifepristone and misoprostol in the United States". New England Journal of Medicine. 338 (18): 1241. doi:10.1056/NEJM199804303381801. PMID 9562577.

- Healthwise (2004). "Manual and vacuum aspiration for abortion". WebMD. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- World Health Organization (2003). "Dilatation and curettage". Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth: A Guide for Midwives and Doctors. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 92-4-154587-9. OCLC 181845530.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - McGee, Glenn. "Abortion". Encarta. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Vause S, Sands J, Johnston TA, Russell S, Rimmer S (2002). "Could some fetocides be avoided by more prompt referral after diagnosis of fetal abnormality?". J Obstet Gynaecol. 22 (3): 243–245. doi:10.1080/01443610220130490. PMID 12521492. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dommergues M, Cahen F, Garel M, Mahieu-Caputo D, Dumez Y (2003). "Feticide during second- and third-trimester termination of pregnancy: opinions of health care professionals". Fetal. Diagn. Ther. 18 (2): 91–97. doi:10.1159/000068068. PMID 12576743. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bhide A, Sairam S, Hollis B, Thilaganathan B (2002). "Comparison of feticide carried out by cordocentesis versus cardiac puncture". Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 20 (3): 230–232. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0705.2002.00797.x. PMID 12230443.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Senat MV, Fischer C, Bernard JP, Ville Y (2003). "The use of lidocaine for fetocide in late termination of pregnancy". BJOG. 110 (3): 296–300. doi:10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.02217.x. PMID 12628271. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Senat MV, Fischer C, Ville Y (2002). "Funipuncture for fetocide in late termination of pregnancy". Prenat. Diagn. 22 (5): 354–356. doi:10.1002/pd.290. PMID 12001185.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nuffield Council on Bioethics (2006). "Clinical perspectives (Continued)". Critical Case Decisions in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine: Ethical Issues. Nuffield Council on Bioethics. ISBN 1-904384-14-5. OCLC 85782378.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Potts, M. et al. "Thousand-year-old depictions of massage abortion," Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care, volume 33, p. 234 (2007): “at Angkor, the operator is a demon.” Also see Mould, R. Mould's Medical Anecdotes, p. 406 (CRC Press 1996).

- Riddle, John M. (1997). Eve's herbs: a history of contraception and abortion in the West. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-27024-X. OCLC 36126503.

- Ciganda C, Laborde A (2003). "Herbal infusions used for induced abortion". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 41 (3): 235–239. doi:10.1081/CLT-120021104. PMID 12807304.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Education for Choice. (2005-05-06). http://www.efc.org.uk/Foryoungpeople/Factsaboutabortion/Unsafeabortion Unsafe abortion. Retrieved 2006-01-11.

- ^ Potts, Malcolm (2002). "History of Contraception". Gynecology and Obstetrics. 6 (8).

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Thapa SR, Rimal D, Preston J (2006). "Self induction of abortion with instrumentation". Aust Fam Physician. 35 (9): 697–698. PMID 16969439. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Grimes DA, Benson J, Singh S; et al. (2006). "Unsafe abortion: the preventable pandemic" (PDF). Lancet. 368 (9550): 1908–19. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69481-6. PMID 17126724.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Grimes DA, Creinin MD (2004). "Induced abortion: an overview for internists". Ann. Intern. Med. 140 (8): 620–6. PMID 15096333.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Grimes DA (2006). "Estimation of pregnancy-related mortality risk by pregnancy outcome, United States, 1991 to 1999". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 194 (1): 92–4. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.070. PMID 16389015.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "The Prevention and Management of Unsafe Abortion" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 1995. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- World Health Organization (1997). Medical Methods for Termination of Pregnancy: Report of a Who Scientific Group. Who Technical Report Series No. 871. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 92-4-120871-6. OCLC 38276325.

- ^ Pregler, Janet P.; DeCherney, Alan H. (2002). Women's health: principles and clinical practice. pmph usa. p. 232. ISBN 978-1550091700.

- Jordi Rello (ed.). Infectious diseases in critical care (2 ed.). Springer. p. 490. ISBN 978-3540344056.

- Botha, Rosanne L.; Bednarek, Paula H.; Kaunitz, Andrew M. (2010). "Complications of Medical and Surgical Abortion". In Guy I Benrubi (ed.). Handbook of Obstetric and Gynecologic Emergencies (4 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 258. ISBN 978-1605476667.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Morgan, Mark; Siddighi, Sam (2004). NMS Obstetrics and Gynecology. National Medical Series for Independent Study (5 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 140. ISBN 978-0781726795.

- Studd, John; Seang, Lin Tan; Chervenak, Frank A. (2007). Progress in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Vol. 17. p. 206. ISBN 978-0443103131.

- "Medical versus surgical methods for first trimester termination of pregnancy". World Health Organization. December 15, 2006. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- Cockburn, Jayne; Pawson, Michael E. (2007). Psychological Challenges to Obstetrics and Gynecology: The Clinical Management. Springer. p. 243. ISBN 978-1846288074.

- Adler NE, David HP, Major BN, Roth SH, Russo NF, Wyatt GE (1990). "Psychological responses after abortion". Science. 248 (4951): 41–44. doi:10.1126/science.2181664. PMID 2181664.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Report of the APA Task Force on Mental Health and Abortion APA (August 13, 2008).

- Grimes DA, Creinin MD (2004). "Induced abortion: an overview for internists". Ann. Intern. Med. 140 (8): 620–626. doi:10.1001/archinte.140.5.620. PMID 15096333.

Abortion does not lead to an increased risk for breast cancer or other late psychiatric or medical sequelae. ... The alleged 'postabortion trauma syndrome' does not exist.

- Stotland NL (2003). "Abortion and psychiatric practice". J Psychiatr Pract. 9 (2): 139–149. doi:10.1097/00131746-200303000-00005. PMID 15985924.

Currently, there are active attempts to convince the public and women considering abortion that abortion frequently has negative psychiatric consequences. This assertion is not borne out by the literature: the vast majority of women tolerate abortion without psychiatric sequelae.

- Stotland NL (1992). "The myth of the abortion trauma syndrome". JAMA. 268 (15): 2078–2079. doi:10.1001/jama.268.15.2078. PMID 1404747.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Henshaw, Stanley K., Singh, Susheela, and Haas, Taylor. (1999). The Incidence of Abortion Worldwide. International Family Planning Perspectives, 25 (Supplement), 30–38. Retrieved 2006-01-18.

- Strauss, L.T., Gamble, S.B., Parker, W.Y, Cook, D.A., Zane, S.B., and Hamdan, S. (November 24, 2006). Abortion Surveillance - United States, 2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 55 (11), 1–32. Retrieved May 10, 2007.

- Finer, Lawrence B. and Henshaw, Stanley K. (2003). Abortion Incidence and Services in the United States in 2000. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 35 (1).'.' Retrieved 2006-05-10.

- Department of Health (2007). "Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2006". Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- Cheng L. “Surgical versus medical methods for second-trimester induced abortion : RHL commentary” (last revised: 1 November 2008). The WHO Reproductive Health Library; Geneva: World Health Organization.

- ^ Bankole, Akinrinola, Singh, Susheela, and Haas, Taylor. (1998). Reasons Why Women Have Induced Abortions: Evidence from 27 Countries. International Family Planning Perspectives, 24 (3), 117–127 and 152. Retrieved 2006-01-18.

- ^ Finer, Lawrence B., Frohwirth, Lori F., Dauphinee, Lindsay A., Singh, Shusheela, and Moore, Ann M. (2005). Reasons U.S. women have abortions: quantative and qualitative perspectives. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 37 (3), 110–118. Retrieved 2006-01-18.

- Jones, Rachel K., Darroch, Jacqueline E., Henshaw, Stanley K. (2002). Contraceptive Use Among U.S. Women Having Abortions in 2000–2001. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 34 (6).'.' Retrieved June 15, 2006.

- Susan A. Cohen: Abortion and Women of Color: The Bigger Picture, Guttmacher Policy Review, Summer 2008, Volume 11, Number 3.

- Devereux, G. (1967). "A typological study of abortion in 350 primitive, ancient, and pre-industrial societies". In Harold Rosen (ed.). Abortion in America; medical, psychiatric, legal, anthropological, and religious considerations. Boston: Beacon Press. OCLC 187445.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Lefkowitz, Mary R. (1992). Women's life in Greece & Rome: a source book in translation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-4474-6. OCLC 25373320. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Sheikh, Sa'diyya (2003). "Family Planning, Contraception, and Abortion in Islam". In Maguire, Daniel C. (ed.). Sacred Rights: The Case for Contraception and Abortion in World Religions. Oxford University Press US. pp. 105–128 . ISBN 0195160010.

- Sheikh, Sa'diyya (2003). "Family Planning, Contraception, and Abortion in Islam". In Maguire, Daniel C. (ed.). Sacred Rights: The Case for Contraception and Abortion in World Religions. Oxford University Press US. pp. 105–128 . ISBN 0195160010.

- "50 Random Facts About ...... Abortion". Random Facts.

- "1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Medicine"

- Riddle, John M. 1992. Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance. London, England: Harvard University Press.

- "History of Prostitution". About.com: Civil Liberties.

- DeHullu, James. "Histories of Abortion". Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- "Abortion Law, History & Religion". Childbirth By Choice Trust. Archived from the original on 2008-02-08. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- Friedlander, Henry (1995). The origins of Nazi genocide: from euthanasia to the final solution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-8078-4675-9. OCLC 60191622.

- Proctor, Robert (1988). Racial Hygiene: Medicine Under the Nazis. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 122, 123 and 366. ISBN 0-674-74578-7. OCLC 20760638.

- Arnot, Margaret L. (1999). Gender and Crime in Modern Europe. New York: Routledge. p. 231. ISBN 1-85728-745-2. OCLC 186748539.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - DiMeglio, Peter M. (1999). "Germany 1933-1945 (National Socialism)". In Helen Tierney (ed.). Women's studies encyclopedia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. M1 589. ISBN 0-313-31072-6. OCLC 38504469.

- Banister, Judith. (1999-03-16). Son Preference in Asia - Report of a Symposium. Retrieved 2006-01-12.

- Mutharayappa, Rangamuthia, Kim Choe, Minja, Arnold, Fred, and Roy, T.K. (1997). Son Preferences and Its Effect on Fertility in India. National Family Health Survey Subject Reports, Number 3.'.' Retrieved 2006-01-12.

- Patel, Rita (1996). "The practice of sex selective abortion in India: May you be the mother of a hundred sons" (PDF). Carolina Papers in International Health and Development. 7. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Sudha, S.; Rajan, S. Irudaya (1999). "Female Demographic Disadvantage in India 1981-1991: Sex Selective Abortions and Female Infanticide". Development and Change. 30 (3): 585–618. doi:10.1111/1467-7660.00130. Archived from the original on 2003-01-01. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Reaney, Patricia. "Selective abortion blamed for India's missing girls". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2006-02-20. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

- Mudur, Ganapati (2002). "India plans new legislation to prevent sex selection". BMJ. 324 (7334): 385b. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7334.385/b.

- Graham, Maureen J.; Larsen; Xu (1998). "Son Preference in Anhui Province, China". International Family Planning Perspectives. 24 (2): 72. doi:10.2307/2991929. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Plafker, Ted (2002). "Sex selection in China sees 117 boys born for every 100 girls". BMJ. 324 (7348): 1233a. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7348.1233/a. PMC 1123206. PMID 12028966.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "China Bans Sex-selection Abortion." (2002-03-22). Xinhua News Agency.'.' Retrieved 2006-01-12.

- ^ World Health Organization. (2004). "Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2000". Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- Salter, C., Johnson, H.B., and Hengen, N. (1997). Care for post abortion complications: saving women's lives. Population Reports, 25 (1).'.' Retrieved 2006-02-22.

- Sedgh, Gilda; Henshaw, S; Singh, S; Ahman, E; Shah, IH (2007). "Induced abortion: estimated rates and trends worldwide" (PDF). The Lancet. 370 (9595): 1338–1345. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61575-X. PMID 17933648. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - World Health Organization. (1998). Address Unsafe Abortion. Retrieved 2006-03-01.

- The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. (2005-11-02). "Public Opinion Supports Alito on Spousal Notification Even as It Favors Roe v. Wade." Pew Research Center Pollwatch.'.' Retrieved 2006-03-01.

- TNS Sofres. (May 2005). European Values. Retrieved January 11, 2007.

- Pew Research Center.(2009). Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- "Mexicans Support Status Quo on Social Issues". Angus Reid Global Monitor. 2005-12-01. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- "Argentines Assess Abortion Changes". Angus Reid Global Monitor. 2004-03-04. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- "Brazilians Want to Keep Abortion as Crime". Angus Reid Global Monitor. 2007-04-12. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- "Colombians Reject Legalizing Abortion". Angus Reid Global Monitor. 2005-08-02. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- Russo J, Russo I (1980). "Susceptibility of the mammary gland to carcinogenesis. II. Pregnancy interruption as a risk factor in tumor incidence". Am J Pathol. 100 (2): 505–506. PMC 1903536. PMID 6773421.

In contrast, abortion is associated with increased risk of carcinomas of the breast. The explanation for these epidemiologic findings is not known, but the parallelism between the DMBA-induced rat mammary carcinoma model and the human situation is striking. ... Abortion would interrupt this process, leaving in the gland undifferentiated structures like those observed in the rat mammary gland, which could render the gland again susceptible to carcinogenesis.

- "Induced abortion does not increase breast cancer risk". World Health Organization. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2004) . The Care of Women Requesting Induced Abortion (PDF). Evidence-based Clinical Guideline Number 7. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. p. 43. ISBN 1-904752-06-3. OCLC 263585758. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-27. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Breast Cancer Risks". United States House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- Koba S, Nowak S (1976). "". Wiadomości lekarskie (in Polish). 29 (3): 221–223. ISSN 0043-5147. PMID 1251638.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Russo J, Russo IH (1980). "Susceptibility of the mammary gland to carcinogenesis. II. Pregnancy interruption as a risk factor in tumor incidence". Am. J. Pathol. 100 (2): 497–512. PMC 1903536. PMID 6773421.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Russo J, Tay L, Russo I (1982). "Differentiation of the mammary gland and susceptibility to carcinogenesis". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2 (1): 5–73. doi:10.1007/BF01805718. PMID 6216933.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Russo J, Russo I (1987). "Biological and molecular bases of mammary carcinogenesis". Laboratory Investigation. 57 (2): 112–137. ISSN 0023-6837. PMID 3302534.

- ^ "Study: Fetus feels no pain until third trimester", Associated Press via MSNBC (2005-08-24). Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- Johnson, Martin and Everitt, Barry. Essential reproduction'.' Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- Weisman, Jonathan. "House to Consider Abortion Anesthesia Bill", Washington Post 2006-12-05. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- Lee SJ, Ralston HJ, Drey EA, Partridge JC, Rosen MA (2005). "Fetal pain: a systematic multidisciplinary review of the evidence". JAMA. 294 (8): 947–954. doi:10.1001/jama.294.8.947. PMID 16118385.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lowery CL, Hardman MP, Manning N, Hall RW, Anand KJS (2007). "Neurodevelopmental Changes of Fetal Pain". Seminars in Perinatology. 31 (5): 275–282. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2007.07.004. PMID 17905181.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Paul, Annie. "The First Ache", New York Times 2008-02-10. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

- Johnson, Martin and Everitt, Barry. Essential reproduction (Blackwell 2000): "The multidimensionality of pain perception, involving sensory, emotional, and cognitive factors may in itself be the basis of conscious, painful experience, but it will remain difficult to attribute this to a fetus at any particular developmental age."'.' Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- Paul, Annie. “The First Ache”, New York Times (2008-02-10).

- Donohue, John J.; Levitt, Steven D. (2001). "The Impact of Legalized Abortion on Crime". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 116 (2): 379–420. doi:10.1162/00335530151144050.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Foote, Christopher L.; Goetz, Christopher F. (2008). "The Impact of Legalized Abortion on Crime: Comment". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 123 (1): 407–423. doi:10.1162/qjec.2008.123.1.407.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Donohue, John J.; Levitt, Steven D. (2008). "Measurement Error, Legalized Abortion, and the Decline in Crime: A Response to Foote and Goetz". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 123 (1): 425–440. doi:10.1162/qjec.2008.123.1.425.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Crime-Abortion Study Continues to Draw Pro-life Backlash". Ohio Roundtable Online Library. The Pro-Life Infonet. 1999-08-11. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

- J.B.F. (2000). "Abortion and the Lower Crime Rate". St. Anthony Messenger. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Knudsen, Lara (2006). Reproductive Rights in a Global Context. Vanderbilt University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0826515282, 9780826515285.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "Obama lifts ban on abortion funds". BBC News. 2009-01-24. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- Resources for Religious Views on Abortion on Patheos

- Garrison, Fielding. An Introduction to the History of Medicine, pp. 566–567 (Saunders 1921).

- Blackstone, William (1979) . "Amendment IX, Document 1". Commentaries on the Laws of England. Vol. 5. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 388. ISBN 3511090288.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Henry de Bracton (1968) . "The crime of homicide and the divisions into which it falls". In George E. Woodbine ed.; Samuel Edmund Thorne trans. (ed.). On the Laws and Customs of England. Vol. 2. p. 341. OCLC 1872.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Lord Ellenborough’s Act (1998). The Abortion Law Homepage.'.' Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- United Nations Population Division. (2002). Abortion Policies: A Global Review. Retrieved February 22, 2007.

- Interactive maps comparing U.S. abortion restrictions by state LawServer.

- "European delegation visits Nicaragua to examine effects of abortion ban (November 26, 2007)". Ipas. Retrieved 2009-06-15. "More than 82 maternal deaths had been registered in Nicaragua since the change. During this same period, indirect obstetric deaths, or deaths caused by illnesses aggravated by the normal effects of pregnancy and not due to direct obstetric causes, have doubled."

- "NICARAGUA: "The Women's Movement Is in Opposition"". Montevideo: Inside Costa Rica. IPS. 28 June 2008.

- Ross, Jen. (September 12, 2006). "In Chile, free morning-after pills to teens." The Christian Science Monitor.'.' Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- Gallardoi, Eduardo. (September 26, 2006). "Morning-After Pill Causes Furor in Chile." The Washington Post.'.' Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- "Surgical Abortion: History and Overview". National Abortion Federation. Retrieved 2006-09-04.

- "Need Abortion, Will Travel author=Marcy Bloom". RH Reality Check. February 25, 2008. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

{{cite web}}: Missing pipe in:|title=(help) - "United States: Percentage of Legal Abortions Obtained by Out-of-State Residents, 2005". The Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- Spencer, James. Sheep Husbandry in Canada, p. 124 (1911).

- "Beef cattle and Beef production: Management and Husbandry of Beef Cattle”, Encyclopaedia of New Zealand (1966).

- McKinnon, Angus et al. Equine Reproduction, p. 563 (Wiley-Blackwell 1993).

- Berger, Joel W (5 May 1983). "Induced abortion and social factors in wild horses". Nature. 303 (5912). London: 59–61. doi:10.1038/303059a0. PMID 6682487.

- Pluháček, Jan; Bartos, L (2000). "Male infanticide in captive plains zebra, Equus burchelli" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 59 (4): 689–694. doi:10.1006/anbe.1999.1371. PMID 10792924.

- Pluháček, Jan (2005). "Further evidence for male infanticide and feticide in captive plains zebra, Equus burchelli" (PDF). Folia Zool. 54 (3): 258–262.

- JW, Fitzpatrick (October 1991). "Changes in herd stallions among feral horse bands and the absence of forced copulation and induced abortion". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 29 (3). Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer: 217–219. ISSN (Print) 1432-0762 (Online) 0340-5443 (Print) 1432-0762 (Online).

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help) - Agoramoorthy, G. (August 1988). "Abortions in free ranging Hanuman langurs (Presbytis entellus)—a male induced strategy?". Human Evolution. 3 (4). Netherlands: Springer: 297–308. ISSN (Print) 1824-310X (Online) 0393-9375 (Print) 1824-310X (Online).

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help)

External links

The following information resources may be created by those with a non-neutral position in the abortion debate:

| Birth control methods | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Related topics | |||||||

| Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) | |||||||

| Sterilization |

| ||||||

| Hormonal contraception |

| ||||||

| Barrier Methods | |||||||

| Emergency Contraception (Post-intercourse) | |||||||

| Spermicides | |||||||

| Behavioral |

| ||||||

| Experimental | |||||||

| Substantive human rights | |

|---|---|

| What is considered a human right is in some cases controversial; not all the topics listed are universally accepted as human rights | |

| Civil and political |

|

| Economic, social and cultural |

|

| Sexual and reproductive | |

| Sexual and reproductive health | |

|---|---|

| Rights | |

| Education | |

| Planning | |

| Contraception | |

| Assisted reproduction |

|

| Health | |

| Pregnancy | |

| Identity | |

| Medicine | |

| Disorders | |

| By country |

|

| History | |

| Policy | |