| Revision as of 15:06, 17 January 2013 view sourceJohnleeds1 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,497 edits →Fall of Abbasids to end of caliphate (1258–1924)← Previous edit | Revision as of 15:27, 17 January 2013 view source Doug Weller (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Oversighters, Administrators264,155 edits as before, replace 'the prophet' with MuhammadNext edit → | ||

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 207: | Line 207: | ||

| * Lapidus (2002), pp. 502–507,845 | * Lapidus (2002), pp. 502–507,845 | ||

| * Lewis (2003), p. 100</ref> | * Lewis (2003), p. 100</ref> | ||

| ===Economy=== | |||

| To reduce the gap between the rich and the poor, Islam encourages trade, <ref>Quran 4:29</ref><ref>International Business Success in a Strange Cultural Environment By Mamarinta P. Mababaya Page 203</ref> discourages the hoarding of wealth<ref>Quran 9:35</ref><ref>Al-Bukhari Vol 2 Hadith 514</ref> and out laws ] <ref>Quran (Al-Baqarah 2:275), (Al-Baqarah 2:276-280), (Al-'Imran 3:130), (Al-Nisa 4:161), (Ar-Rum 30:39)</ref> (the term is '']'' in ]).<ref>{{cite book | title=The Islamic Moral Economy: A Study of Islamic Money and Financial Instruments | author=Karim, Shafiel A. | year=2010 | publisher=Brown Walker Press | location=Boca Raton, FL | isbn=978-1-59942-539-9}}</ref><ref>Financial Regulation in Crisis?: The Role of Law and the Failure of Northern Rock By Joanna Gray, Orkun Akseli Page 97</ref>. Therefore wealth is taxed through ], but trade is not taxed. ] allows the rich to get richer without sharing in the risk. Profit sharing and Venture Capital where the lender is also exposed to risk is acceptable.<ref>Ibn Majah Vol 3 Hadith 2289</ref><ref>International Business Success in a Strange Cultural Environment By Mamarinta P. Mababaya Page 202</ref> <ref>Islamic Capital Markets: Theory and Practice By Noureddine Krichene Page 119</ref> Hoarding of food for speculation is also discouraged. <ref>Abu Daud Hadith 2015</ref> <ref>Ibn Majah Vold 3 Hadith 2154</ref><ref>The Stability of Islamic Finance: Creating a Resilient Financial Environment By Zamir Iqbal, Abbas Mirakhor, Noureddine Krichenne, Hossein Askari Page 75</ref> Grabbing other peoples land is also prohibited. <ref>Al-Bukhari Vol 3 Hadith 632; Vol 4 Hadith 419</ref><ref>Al-Bukhari Vol 3 Hadith 634; Vol 4 Hadith 418</ref> The prohibition of ] has resulted in the development of ] | |||

| ===Military=== | ===Military=== | ||

| Line 261: | Line 257: | ||

| His death in 634 resulted in the succession of ] as the caliph, followed by ], ] and ]. The first caliphs are known as ''al-khulafā' ar-rāshidūn'' ("]"). Under them, the territory under Muslim rule expanded deeply into ] and ] territories.<ref>See | His death in 634 resulted in the succession of ] as the caliph, followed by ], ] and ]. The first caliphs are known as ''al-khulafā' ar-rāshidūn'' ("]"). Under them, the territory under Muslim rule expanded deeply into ] and ] territories.<ref>See | ||

| * Holt (1977a), p.74 | * Holt (1977a), p.74 | ||

| * {{Cite encyclopedia | title=Islam | encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia of Islam Online | author=L. Gardet | coauthors=J. Jomier | ref=harv }}</ref> When Umar was assassinated in 644, ] as successor was met with increasing opposition. The Quran was ] during this time. | * {{Cite encyclopedia | title=Islam | encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia of Islam Online | author=L. Gardet | coauthors=J. Jomier | ref=harv }}</ref> When Umar was assassinated in 644, ] as successor was met with increasing opposition. The Quran was ] during this time. In 656, Uthman was also killed, and Ali assumed the position of caliph. After fighting off opposition in the ] (the "First Fitna"), Ali was assassinated by ] in 661. Following this, ] seized power and began the ], with its capital in ].<ref>Holt (1977a), pp.67–72</ref> | ||

| These disputes over religious and political leadership would give rise to schism in the Muslim community. The majority accepted the legitimacy of the three rulers prior to Ali, and became known as ]s. A minority disagreed, and believed that Ali was the only rightful successor; they became known as the ].<ref>Waines (2003) p.46</ref> After Mu'awiyah's death in 680, conflict over succession broke out again in a civil war known as the "]". The Umayyad dynasty conquered the ], the ], ] and ].<ref>Donald Puchala, ‘’Theory and History in International Relations,’’ page 137. Routledge, 2003.</ref> Local populations of Jews and indigenous Christians, persecuted as religious minorities and taxed heavily, often aided Muslims to take over their lands from the Byzantines and Persians, resulting in exceptionally speedy conquests.<ref>Esposito (2010), p.38</ref><ref>Hofmann (2007), p.86</ref> | |||

| The Umayyad aristocracy viewed Islam as a religion for Arabs only;<ref>Hawting (2000), p.4</ref> their economy was based on taxes from the majority of non-Muslims (]) to the minority of Muslim Arabs. A non-Arab who wanted to convert was required to become a client of an Arab tribe. These new Muslims ('']'') still did not achieve social and economic equality with Arabs. The descendants of Muhammad's uncle ] rallied discontented ''mawali'', poor Arabs, and some Shi'a against the Umayyads and overthrew them with the help of the general ], inaugurating the ] in 750, which moved the capital to ].<ref>Lapidus (2002), p.56; Lewis (1993), pp. 71–83</ref> | |||

| ===Abbasid era (750–1258)=== | ===Abbasid era (750–1258)=== | ||

| Line 299: | Line 295: | ||

| * Lapidus (2002), p.103–143 | * Lapidus (2002), p.103–143 | ||

| * {{Cite encyclopedia | title=Abbasid Dynasty | encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online | ref=harv }}</ref> The ] finally put an end to the Abbassid dynasty, killing its last Caliph at the ]. | * {{Cite encyclopedia | title=Abbasid Dynasty | encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online | ref=harv }}</ref> The ] finally put an end to the Abbassid dynasty, killing its last Caliph at the ]. | ||

| As the Mongol Empire expanded, it also absorbed many Turkish tribes, some of which were Muslim. Therefore at the time of ] the core of the Mongol army consisted of Mongol and Turkish warriors.<ref>Genghis Khan: Conqueror of the World By Leo de Hartog page 52</ref><ref>The Muslim World a Historical Survey Part Ii the Mongol Period By Bertold Spuler, Frank Ronald Charles Bagley</ref><ref>The History of the Mongol Conquests By John Joseph Saunders page 176</ref> The concept of one god was appealing to these tribes and over time many more Turks and the Mongols converted to Islam. ] of the ] converted to Islam in the early fourteenth century <ref>Islam In Russia: The Politics Of Identity And Security By Shireen T. Hunter page 4</ref><ref>Islamization and Native Religion in the Golden Horde: Baba Tükles and ... By Devin A. DeWeese Page 90</ref><ref>Latiurette's History of the expansion of Christianity volume 1 by kenneth scott latourette - Page 289</ref> ] was also a Muslim. Babur the founder of the Mughal Empire was a descendant of ] Lenk a Mongol Emperor. | |||

| ===Fall of Abbasids to end of caliphate (1258–1924)=== | ===Fall of Abbasids to end of caliphate (1258–1924)=== | ||

| Line 325: | Line 319: | ||

| </ref><ref>, Great Moments in Science, ABC Science</ref> This decline was evident culturally; while ] founded an observatory in ] and the Jai Singh Observatory was built in the 18th century, there was not a single Muslim country with a major observatory by the twentieth century.<ref>Ahmed, Imad-ad-Dean. Signs in the heavens. 2. Amana Publications, 2006. pg170. Print. ISBN 1-59008-040-8</ref> The ], launched against Muslim ] in ], succeeded in 1492 and Muslim ] were lost to the ]. By the 19th century the ] had formally ended the last Mughal dynasty in India.<ref>Lapidus (2002), pp.358,378–380,624</ref> The ] after ] and the ] was abolished in 1924.<ref>Lapidus (2002), pp.380,489–493</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2000/488/chrncls.htm |title=New Turkey |publisher=Weekly.ahram.org.eg |date= |accessdate=2010-05-16}}</ref> | </ref><ref>, Great Moments in Science, ABC Science</ref> This decline was evident culturally; while ] founded an observatory in ] and the Jai Singh Observatory was built in the 18th century, there was not a single Muslim country with a major observatory by the twentieth century.<ref>Ahmed, Imad-ad-Dean. Signs in the heavens. 2. Amana Publications, 2006. pg170. Print. ISBN 1-59008-040-8</ref> The ], launched against Muslim ] in ], succeeded in 1492 and Muslim ] were lost to the ]. By the 19th century the ] had formally ended the last Mughal dynasty in India.<ref>Lapidus (2002), pp.358,378–380,624</ref> The ] after ] and the ] was abolished in 1924.<ref>Lapidus (2002), pp.380,489–493</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2000/488/chrncls.htm |title=New Turkey |publisher=Weekly.ahram.org.eg |date= |accessdate=2010-05-16}}</ref> | ||

| Reform and revival movements during this period include an 18th century ] movement led by ] in today's Saudi Arabia. Referred to as Wahhabi, their self designation is Muwahiddun (unitarians). Building upon earlier efforts such as those by the logician ] and ], the movement seeks to uphold monotheism and purify Islam of later ]. Their zeal against ] shrines led to the destruction of sacred tombs in Mecca and Medina, including those Muhammad |

Reform and revival movements during this period include an 18th century ] movement led by ] in today's Saudi Arabia. Referred to as Wahhabi, their self designation is Muwahiddun (unitarians). Building upon earlier efforts such as those by the logician ] and ], the movement seeks to uphold monotheism and purify Islam of later ]. Their zeal against ] shrines led to the destruction of sacred tombs in Mecca and Medina, including those of Muhammad and his Companions.<ref>Esposito (2010), p.146</ref> In the 19th century, the ] and ] movements were initiated. The ] rose to power in ] in 1501 and began conquering Persia in the name of Shi'a Islam. They were toppled in 1722 by the ], which ended their forceful conversion of Sunni lands to Shiaism. | ||

| After their defeat at the hands of the Sunni Ottomans at the ], to unite the Persians behind him ] made conversion mandatory for the largely Sunni population to Shia so that he could get them to fight the Sunni Ottomans.<ref>"Ismail Safavi" Encyclopædia Iranica</ref> They were toppled in 1722 by the ], which ended their forceful conversion of Sunni areas to Shiaism. | |||

| ===Modern times (1924–present)=== | ===Modern times (1924–present)=== | ||

| Line 349: | Line 342: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ].]] | ].]] | ||

| The differences between the Sunnis and the Shia's are primarily political. In the years proceeding prophet Muhammad Imam ] whose teachings most Shia's follow and Imam ] and ] whose teachings most Sunnis follow worked together in Medina. There were very few theological differences between them. The ] by ] quotes 13 hadiths from Imam ].<ref name="Muwatta">Al-Muwatta of Imam Malik Ibn Anas:Translated by Aisha Bewley (Book #5, Hadith #5.9.23)(Book #16, Hadith #16.1.1)(Book #17, Hadith #17.24.43)(Book #20, Hadith #20.10.40)(Book #20, Hadith #20.11.44)(Book #20, Hadith #20.32.108)(Book #20, Hadith #20.39.127)(Book #20, Hadith #20.40.132)(Book #20, Hadith #20.49.167) (Book #20, Hadith #20.57.190)(Book #26, Hadith #26.1.2)(Book #29, Hadith #29.5.17)(Book #36, Hadith #36.4.5)</ref> The political differences between the Sunni and Shia amplified much later. Some of the elite in the old empires of the Middle East felt discontented with the passage of their empires and the Byzantines also benefited when there were political disagreements between the Muslims.<ref>A chronology of Islamic History By H.U.Rahman page 58</ref> In many cases the preislamic customs of the populations that converted to Islam were also absorbed into their rituals.<ref>A Brief History of Saudi Arabia By James Wynbrandt page 64</ref> This also amplified the differences. Most of the differences are regarding Sharia laws devised through ] where there is no such ruling in the Quran or the Hadiths of ] ] regarding a similar case. Therefore the judge continued to use the same ruling as was given in that area during preislamic times, if the population felt comfortable with it, it was just and he used ] to deduce that it did not conflict with the Quran or the Hadith. As explained in the ] by ].<ref name="Coulson"></ref> This made it easier for the different communities to integrate into the Islamic State and assisted in the quick expansion of the Islamic State. Since the | |||

| The ] ({{lang-ar|دستور المدينة}}, Ṣaḥīfat al-Madīnah), was drafted by the ] ] the Jews and the Christians continued to use their own laws in the Islamic State and had their own judges.<ref>R. B. Serjeant, "Sunnah Jami'ah, pacts with the Yathrib Jews, and the Tahrim of Yathrib: analysis and translation of the documents comprised in the so-called 'Constitution of Medina'", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (1978), 41: 1-42, Cambridge University Press.</ref><ref>Watt. Muhammad at Medina and R. B. Serjeant "The Constitution of Medina." Islamic Quarterly 8 (1964) p.4.</ref><ref name="Constitution of Medina"></ref> | |||

| ===Sunni=== | ===Sunni=== | ||

| Line 375: | Line 365: | ||

| * Esposito (2003), pp.275,306 | * Esposito (2003), pp.275,306 | ||

| * {{Cite encyclopedia | title=Shariah | encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online | ref=harv }} | * {{Cite encyclopedia | title=Shariah | encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online | ref=harv }} | ||

| * {{Cite encyclopedia | title=Sunnite | encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online | ref=harv }}</ref> The ] (also known as ] |

* {{Cite encyclopedia | title=Sunnite | encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online | ref=harv }}</ref> The ] (also known as ], or the pejorative term '']'' by its adversaries) is an ultra-orthodox Islamic movement which takes the first generation of Muslims as exemplary models.<ref> GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved on 2010-11-09.</ref> | ||

| ===Shia=== | ===Shia=== | ||

| Line 406: | Line 396: | ||

| ===Other denominations=== | ===Other denominations=== | ||

| * ] is a Messianic movement founded by ] that began in ] in the late 19th century and is practiced by millions of people around the world.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.adherents.com/Na/Na_16.html|title=Ahmadiyya Adherents | publisher=Adherents.com | accessdate=21 February 2011}}</ref> Most mainstream and orthodox Muslims view the Ahmadiyya movement as heretical.<ref>, p. 37, “The Question of Finality of Prophethood”, by Aziz Ahmad Chaudhry, Islam International Publications Limited. |

* ] is a Messianic movement founded by ] that began in ] in the late 19th century and is practiced by millions of people around the world.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.adherents.com/Na/Na_16.html|title=Ahmadiyya Adherents | publisher=Adherents.com | accessdate=21 February 2011}}</ref> Most mainstream and orthodox Muslims view the Ahmadiyya movement as heretical.<ref>, p. 37, “The Question of Finality of Prophethood”, by Aziz Ahmad Chaudhry, Islam International Publications Limited.</ref> | ||

| * The ] is a sect that dates back to the early days of Islam and is a branch of ]. Unlike most Kharijite groups, Ibadism does not regard sinful Muslims as unbelievers. | * The ] is a sect that dates back to the early days of Islam and is a branch of ]. Unlike most Kharijite groups, Ibadism does not regard sinful Muslims as unbelievers. | ||

| * The ] are Muslims who generally reject the ]. | * The ] are Muslims who generally reject the ]. | ||

| Line 659: | Line 649: | ||

| {{Link GA|zh}} | {{Link GA|zh}} | ||

| {{Link FA|eo}} | {{Link FA|eo}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Line 756: | Line 745: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Line 796: | Line 784: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 15:27, 17 January 2013

For other uses, see Islam (disambiguation).

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

| Beliefs |

| Practices |

| History |

| Culture and society |

| Related topics |

Template:Contains Arabic text Islam (English: /ˈɪzlɑːm/; Template:Lang-ar al-ʾislām Template:IPA-ar) is a monotheistic and Abrahamic religion articulated by the Qur'an, a text considered by its adherents to be the verbatim word of God (Template:Lang-ar Allāh) and by the teachings and normative example (called the Sunnah and composed of Hadith) of Muhammad, considered by them to be the last prophet of God. An adherent of Islam is called a Muslim.

Muslims believe that God is one and incomparable and the purpose of existence is to love and serve God. Muslims also believe that Islam is the complete and universal version of a primordial faith that was revealed at many times and places before, including through Abraham, Moses and Jesus, whom they consider prophets. They maintain that the previous messages and revelations have been partially misinterpreted or altered over time, but consider the Arabic Qur'an to be both the unaltered and the final revelation of God. Religious concepts and practices include the five pillars of Islam, which are basic concepts and obligatory acts of worship, and following Islamic law, which touches on virtually every aspect of life and society, providing guidance on multifarious topics from banking and welfare, to warfare and the environment.

Most Muslims are of two denominations, Sunni (75–90%), or Shia (10–20%). About 13% of Muslims live in Indonesia, the largest Muslim-majority country, 25% in South Asia, 20% in the Middle East, and 15% in Sub-saharan Africa. Sizable minorities are also found in China, Russia, and the Americas. Converts and immigrant communities are found in almost every part of the world (see Islam by country). With about 1.57 billion followers or 23% of earth's population, Islam is the second-largest and one of the fastest-growing religions in the world.

Etymology and meaning

Further information: S-L-MIslam is a verbal noun originating from the triliteral root s-l-m which forms a large class of words mostly relating to concepts of wholeness, safeness and peace. In a religious context it means "voluntary submission to God". Muslim, the word for an adherent of Islam, is the active participle of the same verb of which Islām is the infinitive. Believers demonstrate submission to God by serving God and following his commands, and rejecting polytheism. The word sometimes has distinct connotations in its various occurrences in the Qur'an. In some verses (ayat), there is stress on the quality of Islam as an internal conviction: "Whomsoever God desires to guide, He expands his breast to Islam." Other verses connect islām and dīn (usually translated as "religion"): "Today, I have perfected your religion (dīn) for you; I have completed My blessing upon you; I have approved Islam for your religion." Still others describe Islam as an action of returning to God—more than just a verbal affirmation of faith. In the Hadith of Gabriel, islām is presented as one part of a triad that includes imān (faith), and ihsān (excellence), where islām is defined theologically as Tawhid, historically by asserting that Muhammad is messenger of God, and doctrinally by mandating five basic and fundamental pillars of practice.

Articles of faith

Main articles: Aqidah and ImanGod

Main articles: Allah and God in IslamIslam's most fundamental concept is a rigorous monotheism, called tawhīd (Template:Lang-ar). God is described in chapter 112 of the Qur'an as: "Say: He is God, the One and Only; God, the Eternal, Absolute; He begetteth not, nor is He begotten; And there is none like unto Him." (112:1-4) Muslims repudiate the Christian doctrine of the Trinity and divinity of Jesus, comparing it to polytheism. In Islam, God is beyond all comprehension and Muslims are not expected to visualize God. God is described and referred to by certain names or attributes, the most common being Al-Rahmān, meaning "The Compassionate" and Al-Rahīm, meaning "The Merciful" (See Names of God in Islam).

Muslims believe that creation of everything in the universe is brought into being by God’s sheer command “‘Be’ and so it is.” and that the purpose of existence is to love and serve God. He is viewed as a personal god who responds whenever a person in need or distress calls him. There are no intermediaries, such as clergy, to contact God who states "We are nearer to him than (his) jugular vein"

Allāh is the term with no plural or gender used by Muslims and Arabic-speaking Christians and Jews to reference God, while ʾilāh (Template:Lang-ar) is the term used for a deity or a god in general. Other non-Arab Muslims might use different names as much as Allah, for instance "Tanrı" in Turkish or "Khodā" in Persian.

Angels

Main article: Islamic view of angels| Quran |

|---|

History

|

| Divisions |

| Content |

| Reading |

| Translations |

| Exegesis |

| Characteristics |

| Related |

Belief in angels is fundamental to the faith of Islam. The Arabic word for angel (Template:Lang-ar malak) means "messenger", like its counterparts in Hebrew (malakh) and Greek (angelos). According to the Qur'an, angels do not possess free will, and worship God in total obedience. Angels' duties include communicating revelations from God, glorifying God, recording every person's actions, and taking a person's soul at the time of death. They are also thought to intercede on man's behalf. The Qur'an describes angels as "messengers with wings—two, or three, or four (pairs): He adds to Creation as He pleases..."

Revelations

Main articles: Islamic holy books and Qur'an See also: History of the Qur'an

The Islamic holy books are the records which most Muslims believe were dictated by God to various prophets. Muslims believe that parts of the previously revealed scriptures, the Tawrat (Torah) and the Injil (Gospels), had become distorted—either in interpretation, in text, or both. The Qur'an (literally, “Reading” or “Recitation”) is viewed by Muslims as the final revelation and literal word of God and is widely regarded as the finest piece of literature work in the Arabic language.

Muslims believe that the verses of the Qur'an were revealed to Muhammad by God through the archangel Gabriel (Jibrīl) on many occasions between 610 CE until his death on June 8, 632 CE. While Muhammad was alive, all of these revelations were written down by his companions (sahabah), although the prime method of transmission was orally through memorization.

The Qur'an is divided into 114 suras, or chapters, which combined, contain 6,236 āyāt, or verses. The chronologically earlier suras, revealed at Mecca, are primarily concerned with ethical and spiritual topics. The later Medinan suras mostly discuss social and moral issues relevant to the Muslim community. The Qur'an is more concerned with moral guidance than legal instruction, and is considered the "sourcebook of Islamic principles and values". Muslim jurists consult the hadith, or the written record of Prophet Muhammad's life, to both supplement the Qur'an and assist with its interpretation. The science of Qur'anic commentary and exegesis is known as tafsir. Rules governing proper pronunciation is called tajwid.

Muslims usually view "the Qur'an" as the original scripture as revealed in Arabic and that any translations are necessarily deficient, which are regarded only as commentaries on the Qur'an.

Prophets

Prophets in IslamMuslims identify the prophets of Islam (Template:Lang-ar nabī ) as those humans chosen by God to be his messengers. According to the Qur'an the descendants of Abraham were chosen by God to bring the "Will of God" to the peoples of the nations. Muslims believe that prophets are human and not divine, though some are able to perform miracles to prove their claim. Islamic theology says that all of God's messengers preached the message of Islam—submission to the will of God. The Qur'an mentions the names of numerous figures considered prophets in Islam, including Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses and Jesus, among others. Muslims believe that God finally sent Muhammad (Seal of the Prophets) to convey the divine message to the whole world (to sum up and to finalize the word of God). In Islam, the "normative" example of Muhammad's life is called the Sunnah (literally "trodden path"). This example is preserved in traditions known as hadith ("reports"), which recount his words, his actions, and his personal characteristics. Hadith Qudsi is a sub-category of hadith, regarded as the words of God repeated by Muhammad differing from the Quran in that they are "expressed in Muhammad's words", whereas the quran are the "direct words of God". The classical Muslim jurist ash-Shafi'i (d. 820) emphasized the importance of the Sunnah in Islamic law, and Muslims are encouraged to emulate Muhammad's actions in their daily lives. The Sunnah is seen as crucial to guiding interpretation of the Qur'an.

Resurrection and judgment

Main article: QiyamaBelief in the "Day of Resurrection", Yawm al-Qiyāmah (Template:Lang-ar) is also crucial for Muslims. They believe the time of Qiyāmah is preordained by God but unknown to man. The trials and tribulations preceding and during the Qiyāmah are described in the Qur'an and the hadith, and also in the commentaries of scholars. The Qur'an emphasizes bodily resurrection, a break from the pre-Islamic Arabian understanding of death.

On Yawm al-Qiyāmah, Muslims believe all mankind will be judged on their good and bad deeds. The Qur'an lists several sins that can condemn a person to hell, such as disbelief (Template:Lang-ar Kufr), and dishonesty; however, the Qur'an makes it clear God will forgive the sins of those who repent if he so wills. Good deeds, such as charity and prayer, will be rewarded with entry to heaven. Muslims view heaven as a place of joy and bliss, with Qur'anic references describing its features and the physical pleasures to come. Mystical traditions in Islam place these heavenly delights in the context of an ecstatic awareness of God.

Yawm al-Qiyāmah is also identified in the Qur'an as Yawm ad-Dīn (Template:Lang-ar), "Day of Religion"; as-sāʿah (Template:Lang-ar), "the Last Hour"; and al-Qāriʿah (Template:Lang-ar), "The Clatterer."

Predestination

Main article: Predestination in IslamIn accordance with the Islamic belief in predestination, or divine preordainment (al-qadā wa'l-qadar), God has full knowledge and control over all that occurs. This is explained in Qur'anic verses such as "Say: 'Nothing will happen to us except what Allah has decreed for us: He is our protector'..." For Muslims, everything in the world that occurs, good or evil, has been preordained and nothing can happen unless permitted by God. According to Muslim theologians, although events are pre-ordained, man possesses free will in that he has the faculty to choose between right and wrong, and is thus responsible for his actions. According to Islamic tradition, all that has been decreed by God is written in al-Lawh al-Mahfūz, the "Preserved Tablet".

Five pillars

Main article: Five Pillars of IslamThe Pillars of Islam (arkan al-Islam; also arkan ad-din, "pillars of religion") are five basic acts in Islam, considered obligatory for all believers. The Quran presents them as a framework for worship and a sign of commitment to the faith. They are (1) the shahadah (creed), (2) daily prayers (salat), (3) almsgiving (zakah), (4) fasting during Ramadan and (5) the pilgrimage to Mecca (hajj) at least once in a lifetime. The Shia and Sunni sects both agree on the essential details for the performance of these acts.

Testimony

Main article: ShahadahThe Shahadah, which is the basic creed of Islam that must be recited under oath with the specific statement: "'ašhadu 'al-lā ilāha illā-llāhu wa 'ašhadu 'anna muħammadan rasūlu-llāh", or "I testify there are no deities other than God alone and I testify that Muhammad is the Messenger of God." This testament is a foundation for all other beliefs and practices in Islam. Muslims must repeat the shahadah in prayer, and non-Muslims wishing to convert to Islam are required to recite the creed.

Prayer

Main article: Salah See also: Mosque

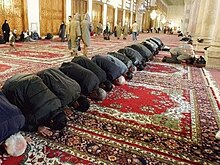

Ritual prayers, called Ṣalāh or Ṣalāt (Arabic: صلاة), must be performed five times a day. Salah is intended to focus the mind on God, and is seen as a personal communication with him that expresses gratitude and worship. Salah is compulsory but flexibility in the specifics is allowed depending on circumstances. The prayers are recited in the Arabic language, and consist of verses from the Qur'an.

A mosque is a place of worship for Muslims, who often refer to it by its Arabic name, masjid. The word mosque in English refers to all types of buildings dedicated to Islamic worship, although there is a distinction in Arabic between the smaller, privately owned mosque and the larger, "collective" mosque (masjid jāmi`). Although the primary purpose of the mosque is to serve as a place of prayer, it is also important to the Muslim community as a place to meet and study. Modern mosques have evolved greatly from the early designs of the 7th century, and contain a variety of architectural elements such as minarets.

Alms-giving

Main articles: Zakat and Sadaqah"Zakāt" (Template:Lang-ar zakāh "alms") is giving a fixed portion of accumulated wealth by those who can afford it to help the poor or needy, and also to assist the spread of Islam. It is considered a religious obligation (as opposed to voluntary charity) that the well-off owe to the needy because their wealth is seen as a "trust from God's bounty". Conservative estimates of annual zakat is estimated to be 15 times global humanitarian aid contributions. The Qur'an and the hadith also urge a Muslim give even more as an act of voluntary alms-giving called ṣadaqah.

Fasting

Main article: Sawm Further information: Sawm of RamadanFasting, (Template:Lang-ar ṣawm), from food and drink (among other things) must be performed from dawn to dusk during the month of Ramadhan. The fast is to encourage a feeling of nearness to God, and during it Muslims should express their gratitude for and dependence on him, atone for their past sins, and think of the needy. Sawm is not obligatory for several groups for whom it would constitute an undue burden. For others, flexibility is allowed depending on circumstances, but missed fasts usually must be made up quickly.

Pilgrimage

Main article: HajjThe pilgrimage, called the ḥajj (Template:Lang-ar ḥaǧǧ) during the Islamic month of Dhu al-Hijjah in the city of Mecca. Every able-bodied Muslim who can afford it must make the pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in his or her lifetime. Rituals of the Hajj include walking seven times around the Kaaba, touching the black stone if possible, walking or running seven times between Mount Safa and Mount Marwah, and symbolically stoning the Devil in Mina.

Law and jurisprudence

Main articles: Sharia and Fiqh| Part of a series on | |||||||

| Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

Ritual

|

|||||||

| Political | |||||||

Family

|

|||||||

Criminal

|

|||||||

| Etiquette | |||||||

Economic

|

|||||||

Hygiene

|

|||||||

| Military | |||||||

| Islamic studies | |||||||

The Sharia (literally "the path leading to the watering place") is Islamic law formed by traditional Islamic scholarship, which most Muslim groups adhere to. In Islam, Sharia is the expression of the divine will, and "constitutes a system of duties that are incumbent upon a Muslim by virtue of his religious belief".

Islamic law covers all aspects of life, from matters of state, like governance and foreign relations, to issues of daily living. The Qur'an defines hudud as the punishments for five specific crimes: unlawful intercourse, false accusation of unlawful intercourse, consumption of alcohol, theft, and highway robbery. Though not in the Qur'an , there are also laws against apostasy (although Muslims disagree over punishment). The Qur'an and Sunnah also contain laws of inheritance, marriage, and restitution for injuries and murder, as well as rules for fasting, charity, and prayer. However, these prescriptions and prohibitions may be broad, so their application in practice varies. Islamic scholars (known as ulema) have elaborated systems of law on the basis of these rules and their interpretations. Over the years there have been changing views on Islamic law but many such as Zahiri and Jariri have since died out.

Fiqh, or "jurisprudence", is defined as the knowledge of the practical rules of the religion. Much of it has evolved to prevent innovation or alteration in the original religion, known as bid'ah. The method Islamic jurists use to derive rulings is known as usul al-fiqh ("legal theory", or "principles of jurisprudence"). According to Islamic legal theory, law has four fundamental roots, which are given precedence in this order: the Qur'an, the Sunnah (the practice of Muhammad), the consensus of the Muslim jurists (ijma), and analogical reasoning (qiyas). For early Islamic jurists, theory was less important than pragmatic application of the law. In the 9th century, the jurist ash-Shafi'i provided a theoretical basis for Islamic law by codifying the principles of jurisprudence (including the four fundamental roots) in his book ar-Risālah.

Jurists

Main articles: Ulama, Sheikh, and ImamThere are many terms in Islam to refer to religiously sanctioned positions of Islam, but "jurist" generally refers to the educated class of Muslim legal scholars engaged in the several fields of Islamic studies. In a broader sense, the term ulema is used to describe the body of Muslim clergy who have completed several years of training and study of Islamic sciences, such as a mufti, qadi, faqih, or muhaddith. Some Muslims include under this term the village mullahs, imams, and maulvis—who have attained only the lowest rungs on the ladder of Islamic scholarship; other Muslims would say that clerics must meet higher standards to be considered ulama (singular Aalim). Some Muslims practise ijtihad whereby they do not accept the authority of clergy.

Etiquette and diet

Main articles: Adab (behavior) and Islamic dietary lawsMany practices fall in the category of adab, or Islamic etiquette. This includes greeting others with "as-salamu `alaykum" ("peace be unto you"), saying bismillah ("in the name of God") before meals, and using only the right hand for eating and drinking. Islamic hygienic practices mainly fall into the category of personal cleanliness and health. Circumcision of male offspring is also practiced in Islam. Islamic burial rituals include saying the Salat al-Janazah ("funeral prayer") over the bathed and enshrouded dead body, and burying it in a grave. Muslims are restricted in their diet. Prohibited foods include pork products, blood, carrion, and alcohol. All meat must come from a herbivorous animal slaughtered in the name of God by a Muslim, Jew, or Christian, with the exception of game that one has hunted or fished for oneself. Food permissible for Muslims is known as halal food.

Family life

See also: Women in IslamThe basic unit of Islamic society is the family, and Islam defines the obligations and legal rights of family members. The father is seen as financially responsible for his family, and is obliged to cater for their well-being. The division of inheritance is specified in the Qur'an, which states that most of it is to pass to the immediate family, while a portion is set aside for the payment of debts and the making of bequests. With some exceptions, the woman's share of inheritance is generally half of that of a man with the same rights of succession. Marriage in Islam is a civil contract which consists of an offer and acceptance between two qualified parties in the presence of two witnesses. The groom is required to pay a bridal gift (mahr) to the bride, as stipulated in the contract. A man may have up to four wives if he believes he can treat them equally, while a woman may have only one husband. In most Muslim countries, the process of divorce in Islam is known as talaq, which the husband initiates by pronouncing the word "divorce". Scholars disagree whether Islamic holy texts justify traditional Islamic practices such as veiling and seclusion (purdah). Starting in the 20th century, Muslim social reformers argued against these and other practices such as polygamy in Islam, with varying success. At the same time, many Muslim women have attempted to reconcile tradition with modernity by combining an active life with outward modesty. Certain Islamist groups like the Taliban have sought to continue traditional law as applied to women.

Government

Main articles: Political aspects of Islam, Islamic state, Islam and secularism, and CaliphateMainstream Islamic law does not distinguish between "matters of church" and "matters of state"; the scholars function as both jurists and theologians. In practice, Islamic rulers frequently bypassed the Sharia courts with a parallel system of so-called "Grievance courts" over which they had sole control. As the Muslim world came into contact with European secular ideals, Muslim societies responded in different ways. Turkey has been governed as a secular state ever since the reforms of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1923. In contrast, the 1979 Iranian Revolution replaced a mostly secular regime with an Islamic republic led by the Ayatollah Khomeini.

Military

Main articles: Jihad, Islamic military jurisprudence, and List of expeditions of MuhammadJihad means "to strive or struggle" (in the way of God) and is sometimes considered the "Sixth Pillar of Islam" albeit by a minority of Sunni Muslim academics. Jihad, in its broadest sense, is classically defined as "exerting one's utmost power, efforts, endeavors, or ability in contending with an object of disapprobation." Depending on the object being a visible enemy, the devil, and aspects of one's own self (such as sinful desires), different categories of jihad are defined. Jihad, when used without any qualifier, is understood in its military aspect. Jihad also refers to one's striving to attain religious and moral perfection. Some Muslim authorities, especially among the Shi'a and Sufis, distinguish between the "greater jihad", which pertains to spiritual self-perfection, and the "lesser jihad", defined as warfare.

Within Islamic jurisprudence, jihad is usually taken to mean military exertion against non-Muslim combatants in the defense or expansion of the Ummah. The ultimate purpose of military jihad is debated, both within the Islamic community and without, with some claiming that it only serves to protect the Ummah, with no aspiration of offensive conflict, whereas others have argued that the goal of Jihad is global conquest. Jihad is the only form of warfare permissible in Islamic law and may be declared against terrorists, criminal groups, rebels, apostates, and leaders or states who oppress Muslims or hamper proselytizing efforts. Most Muslims today interpret Jihad as only a defensive form of warfare: the external Jihad includes a struggle to make the Islamic societies conform to the Islamic norms of justice.

Under most circumstances and for most Muslims, jihad is a collective duty (fard kifaya): its performance by some individuals exempts the others. Only for those vested with authority, especially the sovereign (imam), does jihad become an individual duty. For the rest of the populace, this happens only in the case of a general mobilization. For most Shias, offensive jihad can only be declared by a divinely appointed leader of the Muslim community, and as such is suspended since Muhammad al-Mahdi's occultation in 868 AD.

History

Main articles: Muslim history and Spread of IslamMuhammad (610–632)

Main articles: Muhammad and Muhammad in Islam See also: Early social changes under Islam

In Muslim tradition, Muhammad (c. 570 – June 8, 632) is viewed as the last in a series of prophets. During the last 22 years of his life, beginning at age 40 in 610 CE, according to the earliest surviving biographies, Muhammad reported revelations that he believed to be from God. The content of these revelations, known as the Qur'an, was memorized and recorded by his companions. During this time, Muhammad preached to the people of Mecca, imploring them to abandon polytheism. Although some converted to Islam, Muhammad and his followers were persecuted by the leading Meccan authorities. After 12 years of preaching, Muhammad and the Muslims performed the Hijra ("emigration") to the city of Medina (formerly known as Yathrib) in 622, after initially trying the Aksumite Empire. There, with the Medinan converts (Ansar) and the Meccan migrants (Muhajirun), Muhammad established his political and religious authority. Within years, two battles had been fought against Meccan forces: the Battle of Badr in 624, which was a Muslim victory, and the Battle of Uhud in 625, which ended inconclusively. Conflict with Medinan Jewish clans who opposed the Muslims led to their exile, enslavement, or death, and the Jewish enclave of Khaybar was subdued. In 628, the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah was signed between Mecca and the Muslims and was broken by Mecca two years later. At the same time, Meccan trade routes were cut off as Muhammad brought surrounding desert tribes under his control. By 629 Muhammad was victorious in the nearly bloodless Conquest of Mecca, and by the time of his death in 632 (at the age of 62) he united the tribes of Arabia into a single religious polity.

Caliphate and civil war (632–750)

Further information: Succession to Muhammad, Muslim conquests, and Battle of Karbala

With Muhammad's death in 632, disagreement broke out over who would succeed him as leader of the Muslim community. Abu Bakr, a companion and close friend of Muhammad, was made the first caliph. His immediate task was to avenge a recent defeat by Byzantine forces, although he first had to put down a rebellion by Arab tribes in an episode known as the Ridda wars, or "Wars of Apostasy". The Quran was compiled into one book during this time.

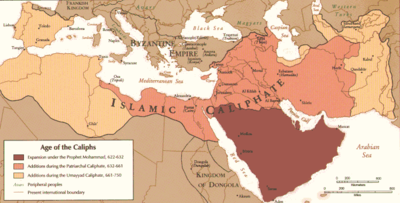

His death in 634 resulted in the succession of Umar ibn al-Khattab as the caliph, followed by Uthman ibn al-Affan, Ali ibn Abi Talib and Hasan ibn Ali. The first caliphs are known as al-khulafā' ar-rāshidūn ("Rightly Guided Caliphs"). Under them, the territory under Muslim rule expanded deeply into Persian and Byzantine territories. When Umar was assassinated in 644, the election of Uthman as successor was met with increasing opposition. The Quran was standardized during this time. In 656, Uthman was also killed, and Ali assumed the position of caliph. After fighting off opposition in the first civil war (the "First Fitna"), Ali was assassinated by Kharijites in 661. Following this, Mu'awiyah seized power and began the Umayyad dynasty, with its capital in Damascus.

These disputes over religious and political leadership would give rise to schism in the Muslim community. The majority accepted the legitimacy of the three rulers prior to Ali, and became known as Sunnis. A minority disagreed, and believed that Ali was the only rightful successor; they became known as the Shi'a. After Mu'awiyah's death in 680, conflict over succession broke out again in a civil war known as the "Second Fitna". The Umayyad dynasty conquered the Maghrib, the Iberian Peninsula, Narbonnese Gaul and Sindh. Local populations of Jews and indigenous Christians, persecuted as religious minorities and taxed heavily, often aided Muslims to take over their lands from the Byzantines and Persians, resulting in exceptionally speedy conquests.

The Umayyad aristocracy viewed Islam as a religion for Arabs only; their economy was based on taxes from the majority of non-Muslims (Dhimmis) to the minority of Muslim Arabs. A non-Arab who wanted to convert was required to become a client of an Arab tribe. These new Muslims (mawali) still did not achieve social and economic equality with Arabs. The descendants of Muhammad's uncle Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib rallied discontented mawali, poor Arabs, and some Shi'a against the Umayyads and overthrew them with the help of the general Abu Muslim, inaugurating the Abbasid dynasty in 750, which moved the capital to Baghdad.

Abbasid era (750–1258)

See also: Islamic Golden Age

Expansion of the Muslim world continued by both conquest and proselytism as both Islam and Muslim trade networks were extending into sub-Saharan West Africa, Central Asia, Volga Bulgaria and the Malay archipelago. The Delhi Sultanate ruled most of the Indian subcontinent. Many Muslims also went to China to trade, virtually dominating the import and export industry of the Song Dynasty.

The major hadith collections were compiled. The Ja'fari jurisprudence was formed from the teachings of Ja'far al-Sadiq while the four Sunni Madh'habs, the Hanafi, Hanbali, Maliki and Shafi'i, were established around the teachings of Abū Ḥanīfa, Ahmad bin Hanbal, Malik ibn Anas and al-Shafi'i respectively. Al-Shafi'i also codified a method to establish the reliability of hadith. Al-Tabari and Ibn Kathir completed the most commonly cited commentaries on the Quran, the Tafsir al-Tabari in the 9th century and the Tafsir ibn Kathir in the 14th century, respectively. Philosophers Al-Farabi and Ibn Sina (Avicenna) sought to incorporate Greek principles into Islamic theology, while others like Al-Ghazzali argued against them and ultimately prevailed.

Caliphs such as Mamun al Rashid and Al-Mu'tasim made the mutazilite philosophy an official creed and imposed it upon Muslims to follow. Mu'tazila was a Greek influenced school of speculative theology called kalam, which refers to dialectic. Many orthodox Muslims rejected mutazilite doctrines and condemned their idea of the creation of the Quran. In inquisitions, Imam Hanbal refused to conform and was tortured and sent to an unlit Baghdad prison cell for nearly thirty months. The other branch of kalam was the Ash'ari school founded by Al-Ash'ari. Some Muslims began to question the piety of indulgence in a worldly life and emphasized poverty, humility and avoidance of sin based on renunciation of bodily desires. Ascetics such as Hasan al-Basri would inspire a movement that would evolve into Sufism. Beginning in the 13th century, Sufism underwent a transformation, largely because of efforts to legitimize and reorganize the movement by Al-Ghazali, who developed the model of the Sufi order—a community of spiritual teachers and students.

Islamic civilization flourished in what is sometimes referred to as the "Islamic Golden Age". Public hospitals established during this time (called Bimaristan hospitals), are considered "the first hospitals" in the modern sense of the word, and issued the first medical diplomas to license doctors of medicine. The Guinness World Records recognizes the University of Al Karaouine, founded in 859, as the world's oldest degree-granting university. The doctorate is argued to date back to the licenses to teach in Muslim law schools. Standards of experimental and quantification techniques, as well as the tradition of citation, were introduced to the scientific process. An important pioneer in this, Ibn Al-Haytham is regarded as the father of the modern scientific method and often referred to as the "world’s first true scientist." The government paid scientists the equivalent salary of professional athletes today. The data used by Copernicus for his heliocentric conclusions was gathered and Al-Jahiz proposed of the theory of natural selection. Rumi wrote some of the finest Persian poetry and is still one of the best selling poets in America. Legal institutions introduced include the trust and charitable trust (Waqf).

The first Muslims states independent of a unified Muslim state emerged from the Berber Revolt (739/740-743). In 930, the Ismaili group known as the Qarmatians unsuccessfully rebelled against the Abbassids, sacked Mecca and stole the Black Stone, which was eventually retrieved. By 1055 the Seljuq Turks had eliminated the Abbasids as a military power but continued the caliph's titular authority. The Mongol Empire finally put an end to the Abbassid dynasty, killing its last Caliph at the Battle of Baghdad in 1258.

Fall of Abbasids to end of caliphate (1258–1924)

Expansion continued with independent powers moving into new areas. Muslim generals such as Saladin recaptured the Holy Land from the Crusades. The Crimean Khanate was one of the strongest regional powers in Europe until the end of the 17th century. The Ottoman Empire conquered the Balkans, where many became Muslim, and reached as far as the gates of Vienna.

While cultural styles used to radiate from Baghdad, the Mongol destruction of Baghdad led Egypt to become the Arab heartland while Central Asia went its own way and was experiencing another golden age. The Muslims in China who were descended from earlier immigration began to assimilate by adopting Chinese names and culture while Nanjing became an important center of Islamic study.

The Muslim world was generally in political decline, especially relative to the non-Islamic European powers. Some Muslim areas are believed to have been depopulated as a result of Mongol destruction and the Black Death. This decline was evident culturally; while Taqi al-Din founded an observatory in Istanbul and the Jai Singh Observatory was built in the 18th century, there was not a single Muslim country with a major observatory by the twentieth century. The Reconquista, launched against Muslim principalities in Iberia, succeeded in 1492 and Muslim Italian states were lost to the Normans. By the 19th century the British Empire had formally ended the last Mughal dynasty in India. The Ottoman era ended after World War I and the Caliphate was abolished in 1924.

Reform and revival movements during this period include an 18th century Salafi movement led by Ibn Abd al-Wahhab in today's Saudi Arabia. Referred to as Wahhabi, their self designation is Muwahiddun (unitarians). Building upon earlier efforts such as those by the logician Ibn Taymiyyah and Ibn al-Qayyim, the movement seeks to uphold monotheism and purify Islam of later innovations. Their zeal against idolatrous shrines led to the destruction of sacred tombs in Mecca and Medina, including those of Muhammad and his Companions. In the 19th century, the Deobandi and Barelwi movements were initiated. The Safavid dynasty rose to power in Tabriz in 1501 and began conquering Persia in the name of Shi'a Islam. They were toppled in 1722 by the Hotaki dynasty, which ended their forceful conversion of Sunni lands to Shiaism.

Modern times (1924–present)

Further information: Iranian revolution and Islamic revival

Contact with industrialized nations brought Muslim populations to new areas through economic migration. Many Muslims migrated as indentured servants, from mostly India and Indonesia, to the Caribbean, forming the largest Muslim populations by percentage in the Americas. The resulting urbanization and increase in trade in sub-Saharan Africa brought Muslims to settle in new areas and spread their faith, likely doubling the Muslims population between 1869 and 1914. Muslim immigrants, many as guest workers, began arriving, largely from former colonies, into several Western European nations since the 1960s.

New Muslim intellectuals are beginning to arise, and are increasingly separating perennial Islamic beliefs from archaic cultural traditions. Liberal Islam is a movement that attempts to reconcile religious tradition with modern norms of secular governance and human rights. Its supporters say that there are multiple ways to read Islam's sacred texts, and stress the need to leave room for "independent thought on religious matters". Women's issues receive a significant weight in the modern discourse on Islam because the family structure remains central to Muslim identity.

Secular powers such as Chinese Red Guards closed many mosques and destroyed Qurans and Communist Albania became the first country to ban the practice of every religion. In Turkey, the military carried out coups to oust Islamist governments and headscarves were, as well as in Tunisia, banned in official buildings. About half a million Muslims were killed in Cambodia by communists whom, it is argued, viewed them as their primary enemy and wished to exterminate them since they stood out and worshipped their own god. However, Islamist groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood advocate Islam as a comprehensive political solution, often in spite of being banned. Jamal-al-Din al-Afghani, along with his acolyte Muhammad Abduh, have been credited as forerunners of the Islamic revival. In Iran, revolution replaced secular regime with an Islamic state. In Turkey, the Islamist AK Party has democratically been in power for about a decade, while Islamist parties are doing well in elections following the Arab Spring. The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), consisting of Muslim countries, was established in 1969 after the burning of the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.

Piety appears to be deepening worldwide. Orthodox groups are sometimes well funded and are growing at the expense of traditional groups. In many places, the prevalence of the Islamic veil is growing increasingly common and the percentage of Muslims favoring Sharia laws has increased. With religious guidance increasingly available electronically, Muslims are able to access views that are strict enough for them rather than rely on state clerics who are often seen as stooges. Some organizations began using the media to promote Islam such as the 24-hour TV channel, Peace TV. Perhaps as a result of these efforts, most experts agree that Islam is growing faster than any other faith in East and West Africa.

Denominations

Main article: Islamic schools and branches

Sunni

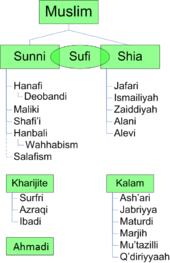

Main article: Sunni IslamThe largest denomination in Islam is Sunni Islam, which makes up over 75% to 90% of all Muslims. Sunni Muslims also go by the name Ahl as-Sunnah which means "people of the tradition ". This example is preserved in traditions known as Al-Kutub Al-Sittah (six major books) which are hadiths ("reports"), recounting his words, his actions, and his personal characteristics. Sunnis believe that the first four caliphs were the rightful successors to Muhammad; since God did not specify any particular leaders to succeed him, those leaders had to be elected. Sunnis believe that a caliph should be chosen by the whole community.

There are four recognised madh'habs (schools of thought): Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, and Hanbali. All four accept the validity of the others and a Muslim may choose any one that he or she finds agreeable. The Salafi (also known as Ahl al-Hadith, or the pejorative term Wahhabi by its adversaries) is an ultra-orthodox Islamic movement which takes the first generation of Muslims as exemplary models.

Shia

Main article: Shia IslamThe Shi'a constitute 10–20% of Islam and are its second-largest branch. While Sunnis believe that Muhammad did not appoint a successor, Shias believe that during The Farewell Pilgrimage Muhammad appointed his son-in-law, Ali ibn Abi Talib, as his successor as shown by the Hadith of the pond of Khumm. As a result, they believe that Ali ibn Abi Talib was the first Imam (leader), rejecting the legitimacy of the previous Muslim caliphs since they were not appointed by Muhammad. Shias believe that the political and religious leadership of Imams come from the direct descendants of Muhammad and Ali, also known as the Ahl al-Bayt. To most Shias, an Imam rules by right of divine appointment and holds "absolute spiritual authority" among Muslims, having final say in matters of doctrine and revelation. However, the Imams are not allowed to introduce new laws or eradicate old ones; they are simply required to interpret and reflect the will of Allah and Muhammad.

Shia Islam has several branches, the largest of which is the Twelvers, followed by Zaidis and Ismailis. After the death of Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq, considered the sixth Imam by the Shia's the Ismailis started to follow his son Isma'il ibn Jafar and the Ithna Asheri division, the followers of the twelve Imams started to follow his other son Musa al-Kazim as their seventh Imam. The Zaydis follow Zayd ibn Ali the uncle of Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq as their fifth Imam. The Twelvers believe that there were 12 Imams or caliphs after Muhammad. They often cite the Hadith of the Twelve Successors as evidence. Shias prefer hadiths attributed to the Ahlul Bayt and close associates. The Twelver Shi'a follow a legal tradition called Ja'fari jurisprudence. Other smaller groups, include the Bohra, and Druze, as well as the Alawites and Alevi. Some Shia branches label other Shia branches that do not agree with their doctrine as Ghulat.

Sufism

Main article: Sufism

Sufism is a mystical-ascetic approach to Islam that seeks to find divine love and knowledge through direct personal experience of God. By focusing on the more spiritual aspects of religion, Sufis strive to obtain direct experience of God by making use of "intuitive and emotional faculties" that one must be trained to use. However, Sufism has been criticized by the Salafi sect for what they see as an unjustified religious innovation. Many Sufi orders, or tariqas, can be classified as either Sunni or Shi'a, but others classify themselves simply as 'Sufi'.

Other denominations

- Ahmadiyya is a Messianic movement founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad that began in India in the late 19th century and is practiced by millions of people around the world. Most mainstream and orthodox Muslims view the Ahmadiyya movement as heretical.

- The Ibadi is a sect that dates back to the early days of Islam and is a branch of kharijite. Unlike most Kharijite groups, Ibadism does not regard sinful Muslims as unbelievers.

- The Quranists are Muslims who generally reject the Hadith.

- Yazdânism is seen as a blend of local Kurdish beliefs and Islamic Sufi doctrine introduced to Kurdistan by Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir in the 12th century.

- Nation of Islam (NOI) is a primarily African-American new religious movement founded in Detroit during the 20th century.

- Karaite-Karaism or Karaimism a transitional religion between Mosaism and proto-Shiism, was brought from Khorezm to the Sabians of the Bosporan Kingdom (Southern Russia) after the Umayyad attack of 712AD.

Demographics

Main articles: Muslim world and Ummah See also: List of countries by Muslim population

A comprehensive 2009 demographic study of 232 countries and territories reported that 23% of the global population, or 1.57 billion people, are Muslims. Of those, it's estimated over 75–90% are Sunni and 10–20% are Shi'a, with a small minority belonging to other sects. Approximately 50 countries are Muslim-majority, and Arabs account for around 20% of all Muslims worldwide. Between 1900 and 1970 the global Muslim community grew from 200 million to 551 million; between 1970 and 2009 Muslim population increased more than three times to 1.57 billion.

The majority of Muslims live in Asia and Africa. Approximately 62% of the world's Muslims live in Asia, with over 683 million adherents in Indonesia, Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh. In the Middle East, non-Arab countries such as Turkey and Iran are the largest Muslim-majority countries; in Africa, Egypt and Nigeria have the most populous Muslim communities.

Most estimates indicate that the People's Republic of China has approximately 20 to 30 million Muslims (1.5% to 2% of the population). However, data provided by the San Diego State University's International Population Center to U.S. News & World Report suggests that China has 65.3 million Muslims. Islam is the second largest religion after Christianity in many European countries, and is slowly catching up to that status in the Americas, with between 2,454,000, according to Pew Forum, and approximately 7 million Muslims, according to the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), in the United States.

Culture

The term "Islamic culture" could be used to mean aspects of culture that pertain to the religion, such as festivals and dress code. It is also controversially used to mean the culture of traditionally Muslim people. "Islamic civilization" may also refer to the aspects of the synthesized culture of the early Caliphates, including that of non-Muslims.

Architecture

Main article: Islamic architecturePerhaps the most important expression of Islamic art is architecture, particularly that of the mosque (four-iwan and hypostyle). Through the edifices, the effect of varying cultures within Islamic civilization can be illustrated. The North African and Spanish Islamic architecture, for example, has Roman-Byzantine elements, as seen in the Great Mosque of Kairouan which contains marble and porphyry columns from Roman and Byzantine buildings, in the Alhambra palace at Granada, or in the Great Mosque of Cordoba.

Art

Main article: Islamic artIslamic art encompasses the visual arts produced from the 7th century onwards by people (not necessarily Muslim) who lived within the territory that was inhabited by Muslim populations. It includes fields as varied as architecture, calligraphy, painting, and ceramics, among others.

Making images of human beings and animals is frowned on in many Islamic cultures and connected with laws against idolatry common to all Abrahamic religions, as 'Abdullaah ibn Mas'ood reported that Muhammad said, "Those who will be most severely punished by Allah on the Day of Resurrection will be the image-makers." (Reported by al-Bukhaari, see al-Fath, 10/382). However this rule has been interpreted in different ways by different scholars and in different historical periods, and there are examples of paintings of both animals and humans in Mughal, Persian and Turkish art. The existence of this aversion to creating images of animate beings has been used to explain the prevalence of calligraphy, tessellation and pattern as key aspects of Islamic artistic culture.

Calendar

Main article: Islamic calendarThe formal beginning of the Muslim era was chosen to be the Hijra in 622 CE, which was an important turning point in Muhammad's fortunes. The assignment of this year as the year 1 AH (Anno Hegirae) in the Islamic calendar was reportedly made by Caliph Umar. It is a lunar calendar with days lasting from sunset to sunset. Islamic holy days fall on fixed dates of the lunar calendar, which means that they occur in different seasons in different years in the Gregorian calendar. The most important Islamic festivals are Eid al-Fitr (Template:Lang-ar) on the 1st of Shawwal, marking the end of the fasting month Ramadan, and Eid al-Adha (عيد الأضحى) on the 10th of Dhu al-Hijjah, coinciding with the pilgrimage to Mecca.

Criticism of Islam

Main article: Criticism of IslamCriticism of Islam has existed since Islam's formative stages. Early written criticism came from Christians, prior to the ninth century, many of whom viewed Islam as a radical Christian heresy. Later there appeared criticism from the Muslim world itself, and also from Jewish writers and from ecclesiastical Christians.

Objects of criticism include the morality of the life of Muhammad, the last prophet of Islam, both in his public and personal life. Issues relating to the authenticity and morality of the Qur'an, the Islamic holy book, are also discussed by critics. Other criticisms focus on the question of human rights in modern Islamic nations, and the treatment of women in Islamic law and practice. In wake of the recent multiculturalism trend, Islam's influence on the ability of Muslim immigrants in the West to assimilate has been criticized.

See also

Main article: Outline of Islam|

Template:Misplaced Pages books

|

References

Notes

- There are ten pronunciations of Islam in English, differing in whether the first or second syllable has the stress, whether the s is /z/ or /s/, and whether the a is pronounced /ɑː/, /æ/ or (when the stress is on the first syllable) /ə/ (Merriam Webster). The most common are /ˈɪzləm, ˈɪsləm, ɪzˈlɑːm, ɪsˈlɑːm/ (Oxford English Dictionary, Random House) and /ˈɪzlɑːm, ˈɪslɑːm/ (American Heritage Dictionary).

- /ʔiˈslaːm/: Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from [i]~[ɪ]~[e]. The second vowel ranges from [æ]~[a]~[ä]~[ɛ]. At some geographic regions, such as Northwestern Africa they don't have stress.

Citations

- See:

- Quran 51:56

- "God". Islam: Empire of Faith. PBS. Retrieved 2010-12-18.

For Muslims, God is unique and without equal.

- ^ "Human Nature and the Purpose of Existence". Patheos.com. Retrieved 2011-01-29.

- "People of the Book". Islam: Empire of Faith. PBS. Retrieved 2010-12-18.

- ^ See: * Accad (2003): According to Ibn Taymiya, although only some Muslims accept the textual veracity of the entire Bible, most Muslims will grant the veracity of most of it. * Esposito (1998), pp.6,12* Esposito (2002b), pp.4–5* F. E. Peters (2003), p.9* F. Buhl. "Muhammad". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)* Hava Lazarus-Yafeh. "Tahrif". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bennett (2010), p.101

- Esposito (2002b), p.17

- See: * Esposito (2002b), pp.111,112,118* "Shari'ah". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ See:

- "Sunnite". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

They numbered about 900 million in the late 20th century and constituted nine-tenths of all the adherents of Islām.

- Islamic Beliefs, Practices, and Cultures. Marshall Cavendish. 2010. p. 352. ISBN 0-7614-7926-0. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

A common compromise figure ranks Sunnis at 90 percent.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population". Pew Research Center. October 7, 2009. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

Of the total Muslim population, 10-13% are Shia Muslims and 87-90% are Sunni Muslims.

- "Quick guide: Sunnis and Shias". BBC News. 2011-12-06. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

The great majority of Muslims are Sunnis - estimates suggest the figure is somewhere between 85% and 90%.

- Sunni Islam: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide "Sunni Islam is the dominant division of the global Muslim community, and throughout history it has made up a substantial majority (85 to 90 percent) of that community."

- "Sunni and Shia Islam". Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

Sunni constitute 85 percent of the world's Muslims.

- "Sunni". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

Sunni Islam is the largest denomination of Islam, comprising about 85% of the world's over 1.5 billion Muslims.

- "Tension between Sunnis, Shiites emerging in USA". USA Today. 2007-09-24. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

Among the world's estimated 1.4 billion Muslims, about 85% are Sunni and about 15% are Shiite.

- Inside Muslim minds "around 80% are Sunni"

- Who Gets To Narrate the World "The Sunnis (approximately 80%)"

- A world theology N. Ross Reat "80% being the Sunni"

- Islam and the Ahmadiyya jama'at "The Sunni segment, accounting for at least 80% of the worlds Muslim population"

- Eastern Europe Russia and Central Asia "some 80% of the worlds Muslims are Sunni"

- A dictionary of modern politics "probably 80% of the worlds Muslims are Sunni"

- "Religions". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

Sunni Islam accounts for over 75% of the world's Muslim population...

- "Sunnite". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ See

- "Shīʿite". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

Shīʿites have come to account for roughly one-tenth of the Muslim population worldwide.

- "Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population". Pew Research Center. October 7, 2009. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

The Pew Forum's estimate of the Shia population (10-13%) is in keeping with previous estimates, which generally have been in the range of 10-15%. Some previous estimates, however, have placed the number of Shias at nearly 20% of the world's Muslim population.

- "Shia". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

Shi'a Islam is the second largest branch of the tradition, with up to 200 million followers who comprise around 15% of all Muslims worldwide...

- "Religions". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

Shia Islam represents 10-20% of Muslims worldwide...

- Iran, Israel and the United States "The majority of the world's Islamic population, which is Sunni, accounts for over 75% of the Islamic population; the other 10-20 percent is Shia." (reference: CIA)

- Sue Hellett; U.S. should focus on sanctions against Iran "Let me review, while Shia Islam makes up only 10-20 percent of the world’s Muslim population, Iraq has a Shia majority (between 60-65 percent), but had a Sunni controlled government under Saddam Hussein and cronies from 1958-2003... (If you like government figures, see the CIA World Factbook.)"

- "Shīʿite". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- ^ Miller (2009), pp.8,17

- See:* Esposito (2002b), p.21* Esposito (2004), pp.2,43 * Miller (2009), pp.9,19

- ^

Miller, Tracy, ed. (2009). Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Muslim Population (PDF). Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - http://articles.cnn.com/2009-10-07/world/muslim.world.population_1_god-but-god-middle-east-distant?_s=PM:WORLD

- "The World Factbook". CIA Factbook. Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- According to some sources it is the third fastest-growing religion after Zoroastrianism and Bahá'í in relative numbers and second fastest-growing in absolute numbers after Christianity. Israel haven for new Bahai world order, Fastest Growing Religion

- "The List: The World's Fastest-Growing Religions". Foreign Policy. May 14, 2007. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ^

- "Islam Today". Islam: Empire of Faith (2000). PBS. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

Islam, followed by more than a billion people today, is the world's fastest growing religion and will soon be the world's largest...

- "No God But God". Thomas W. Lippman. U.S. News & World Report. April 7, 2008. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

Islam is the youngest, the fastest growing, and in many ways the least complicated of the world's great monotheistic faiths. It is a unique religion based on its own holy book, but it is also a direct descendant of Judaism and Christianity, incorporating some of the teachings of those religions—modifying some and rejecting others.

- "Understanding Islam". Susan Headden. U.S. News & World Report. April 7, 2008. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- "Major Religions of the World Ranked by Number of Adherents". Adherents.com. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- "Islam Today". Islam: Empire of Faith (2000). PBS. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- Dictionary listing for Siin roots derived from Lane's Arabic-English Lexicon via www.studyquran.co.uk

- Lewis, Barnard; Churchill, Buntzie Ellis. Islam: The Religion and The People. Wharton School Publishing. 2009. pp. 8. Books.google.com. 2009. ISBN 9780132230858. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- What does Islam mean? The Friday Journal, Mumbai (6 Feb 2011)

- See:

- Quran 5:3, Quran 3:19, Quran 3:83

- See:

- Esposito, John L. (2000-04-06). The Oxford History of Islam. Oxford University Press. pp. 76–77. ISBN 9780195107999.

- Mahmutćehajić, Rusmir (2006). The mosque: the heart of submission. Fordham University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-8232-2584-2.

- See:

- Quran 112:1–4

- Esposito (2002b), pp.74–76

- Esposito (2004), p.22

- Griffith (2006), p.248

- D. Gimaret. "Allah, Tawhid". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Bentley, David (1999). The 99 Beautiful Names for God for All the People of the Book. William Carey Library. ISBN 0-87808-299-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Islām". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- Quran 2:117

- Quran 51:56

- Quran 2:186

- Quran 50:16

- See:

- "God". Islam: Empire of Faith. PBS. Retrieved 2010-12-18.

- "Islam and Christianity", Encyclopedia of Christianity (2001): Arabic-speaking Christians and Jews also refer to God as Allāh.

- L. Gardet. "Allah". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Quran 21:19–20, Quran 35:1

- See:

- Quran 35:1

- Esposito (2002b), pp.26–28

- W. Madelung. "Malā'ika". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gisela Webb. "Angel". Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Chejne, A. (1969) The Arabic Language: Its Role in History, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

- Speicher, K. (1997) in: Edzard, L., and Szyska, C. (eds.) Encounters of Words and Texts: Intercultural Studies in Honor of Stefan Wild. Georg Olms, Hildesheim, pp. 43–66.

- Esposito (2004), pp.17,18,21

- Al Faruqi (1987). "The Cantillation of the Qur'an". Asian Music (Autumn – Winter 1987): 3–4.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - See:

- "Islam". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Qur'an". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- "Islam". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Esposito (2004), p.79

- See:

- Esposito (2004), pp.79–81

- "Tafsir". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- See:

- Teece (2003), pp.12,13

- C. Turner (2006), p.42

- "Qur'an". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help): The word Qur'an was invented and first used in the Qur'an itself. There are two different theories about this term and its formation.

- "The Koran". Quod.lib.umich.edu. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- See:

- Momem (1987), p.176

- "Islam". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- See:

- Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World (2003), p.666

- J. Robson. "Hadith". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - D. W. Brown. "Sunna". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- See:

- "Resurrection", The New Encyclopedia of Islam (2003)

- "Avicenna". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help): Ibn Sīnā, Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Sīnā is known in the West as "Avicenna". - L. Gardet. "Qiyama". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Quran 5:31

- See:

- Smith (2006), p.89; Encyclopedia of Islam and Muslim World, p.565

- "Heaven", The Columbia Encyclopedia (2000)

- Asma Afsaruddin. "Garden". Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Paradise". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Quran 1:4

- Quran 6:31

- Quran 101:1

- See:

- Quran 9:51

- D. Cohen-Mor (2001), p.4: "The idea of predestination is reinforced by the frequent mention of events 'being written' or 'being in a book' before they happen: 'Say: "Nothing will happen to us except what Allah has decreed for us..." ' "

- Ahmet T. Karamustafa. "Fate". Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help): The verb qadara literally means "to measure, to determine". Here it is used to mean that "God measures and orders his creation".

- See:

- Farah (2003), pp.119–122

- Patton (1900), p.130

- Pillars of Islam, Oxford Islamic Studies Online

- Hossein Nasr The Heart of Islam, Enduring Values for Humanity (April., 2003), pp 3, 39, 85, 27–272

- See:

- Farah (1994), p.135

- Momen (1987), p.178

- "Islam", Encyclopedia of Religious Rites, Rituals, and Festivals(2004)

- ArticleClick.com

- See:

- Esposito (2002b), pp.18,19

- Hedáyetullah (2006), pp.53–55

- Kobeisy (2004), pp.22–34

- Momen (1987), p.178

- Budge, E.A. Wallis (June 13, 2001). Budge's Egypt: A Classic 19th century Travel Guide. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 123–128. ISBN 0-486-41721-2.

- See:

- J. Pedersen. "Masdjid". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Mosque". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- J. Pedersen. "Masdjid". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.

- "Analysis: A faith-based aid revolution in the Muslim world?". irinnews.org. 2012-06-01. Retrieved 2012-12-02.

- See:

- Quran 2:177

- Esposito (2004), p.90

- "Zakat". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Zakat". Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- See:

- Quran 2:184

- Esposito (2004), pp.90,91

- "Islam". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- See:

- Farah (1994), pp.145–147

- Goldschmidt (2005), p.48

- "Hajj". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- "Shari'ah". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.