| Revision as of 00:58, 21 February 2007 edit204.50.113.28 (talk) →Composition← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 05:08, 7 January 2025 edit undoJMons (talk | contribs)237 edits Added parliament proroguement/suspension and moved official languages of parliament into another paragraph | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Bicameral federal legislature of Canada}} | |||

| {{Canadian politics}} | |||

| {{Use Canadian English|date=February 2020}} | |||

| The '''Parliament of Canada ''' (]: ''Parlement du Canada'') is ]'s ], seated at ] in ], ]. According to Section 17 of the ], Parliament consists of three components: the ] (''la Couronne''), the ] (''le Sénat''), and the ] (''la Chambre des communes''). The Sovereign is normally represented by the ], who appoints the 105 members of the Senate on the recommendation of the Prime Minister. The 308 members of the House of Commons are directly elected by the people, with each member representing a single ], frequently called a constituency or a "]" in Canadian English. | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2018}} | |||

| {{Infobox legislature | |||

| | background_color = Maroon | |||

| | name = Parliament of Canada | |||

| | native_name = {{nobold|{{lang|fr|Parlement du Canada}}}} | |||

| | transcription_name = | |||

| | foundation = {{start date|df=yes|1867|07|1}} | |||

| | preceded_by = Initially assumed some ] from: | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| Later added some jurisdiction from: | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] (]) | |||

| * ] | |||

| | legislature = ] | |||

| | coa_pic = Parliament of Canada Badge.png | |||

| | coa_res = 150px | |||

| | house_type = Bicameral | |||

| | houses = {{ubl | ] | ]}} | |||

| | leader1_type = ] | |||

| | leader1 = ] | |||

| | election1 = 8 September 2022 | |||

| | leader2_type = ] | |||

| | leader2 = ] | |||

| | election2 = 26 July 2021 | |||

| | leader3_type = ] | |||

| | leader3 = ] | |||

| | election3 = 12 May 2023 | |||

| | party3 = ] | |||

| | leader4_type = ] | |||

| | leader4 = ] | |||

| | party4 = ] | |||

| | election4 = 3 October 2023 | |||

| | leader5_type = ] | |||

| | leader5 = ] | |||

| | party5 = ] | |||

| | election5 = 4 November 2015 | |||

| | leader6 = ] | |||

| | party6 = ] | |||

| | leader6_type = ] | |||

| | election6 = 10 September 2022 | |||

| | members = {{ubl | '''443''' | 105 senators | 338 ]}} | |||

| | house1 = ] | |||

| | structure1 = Senate_of_Canada_-_Seating_Plan_(44th_Parliament).svg | |||

| | structure1_res = 200px | |||

| | structure1_alt = Current Structure of the Canadian Senate | |||

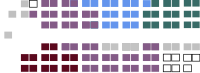

| | political_groups1 = {{nowrap|{{legend|{{Canadian party colour|CA|ISG}}|] (40)}}}} | |||

| {{nowrap|{{legend|{{Canadian party colour|CA|CSG}}|] (16)}}}} | |||

| {{nowrap|{{legend|{{Canadian party colour|CA|Conservative}}|] (15)}}}} | |||

| {{nowrap|{{legend|{{Canadian party colour|CA|Progressive Senate Group}}|] (14)}}}} | |||

| {{nowrap|{{legend|{{Canadian party colour|CA|Non-affiliated}}|] (10)}}}} | |||

| {{legend|white|Vacant (10)}} | |||

| | voting_system1 = Appointment by the ] on ] of the ] | |||

| | last_election1 = | |||

| | house2 = ] | |||

| | structure2 = File:44th Canadian Parliament.svg | |||

| | structure2_res = 300px | |||

| | structure2_alt = Current Structure of the Canadian House of Commons | |||

| | political_groups2 = | |||

| ''']''' | |||

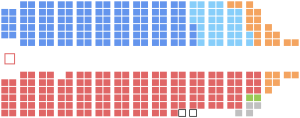

| * {{Colour box|#F08080|border=silver}} ] (153) | |||

| {{nowrap|''']'''}} | |||

| * {{Colour box|#6495ED|border=silver}} ] (120) | |||

| ''']''' | |||

| * {{Colour box|#87CEFA|border=silver}} ] (33) | |||

| * {{Colour box|#F4A560|border=silver}} ] (25)<ref>{{cite web |last1=Honderich |first1=Holly |title=Canada's NDP pulls support for Trudeau's Liberals |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cm2n00e3z87o |website=bbc.com |publisher=British Broadcasting Corporation |access-date=4 September 2024}}</ref> | |||

| '''Parties without official status''' | |||

| * {{Colour box|#99C955|border=silver}} ] (2) | |||

| * {{Colour box|#DDDDDD|border=silver}} ] (4) | |||

| * {{Colour box|#FFFFFF|border=silver}} Vacant (1) | |||

| | voting_system2 = ] | |||

| | last_election2 = ] | |||

| | session_room = Centre Block - Parliament Hill.jpg | |||

| | session_res = 200px | |||

| | session_alt = House of Commons of Canada sits in the West Block in Ottawa until 2029 | |||

| | meeting_place = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] – ], 2 Rideau Street, Ottawa, Ontario | |||

| * ] – ] – ], Ottawa, Ontario | |||

| }} | |||

| | website = {{URL|https://parl.ca}} | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''Parliament of Canada''' ({{langx|fr|Parlement du Canada}}) is the ] ] of ], seated at ] in ], and is composed of three parts: the ], the ], and the ].<ref name=CA1867-17></ref> By ], the House of Commons is dominant, with the Senate rarely opposing its will. The Senate reviews legislation from a less partisan standpoint and may initiate certain bills. The monarch or his representative, normally the ] bullet 3 and table column 2 example 1. Any proposal for modification to the guideline should be posted at its talk page.-->]], provides ] to make bills into law. According to Section 16 of the ], the official languages of the parliament are ] and ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/const/page-12.html#h-47|title=CONSTITUTION ACT, 1982|publisher=Government of Canada|website=laws-lois.justice.gc.ca|access-date=January 7, 2025}}</ref> | |||

| The ], the House of Commons, is the dominant branch of the Canadian Parliament. The ], the Senate, rarely opposes the will of the other Chamber, and the duties of the Sovereign and Governor General are largely ceremonial, as in theory he or she could refuse to sign a bill, and could dismiss the cabinet and call an election unprompted. The Prime Minister and Cabinet must retain the support of a majority of members of the Lower House in order to remain in office; they need not have the confidence of the Upper House. | |||

| The governor general, on behalf of the monarch, summons and appoints the 105 senators on the ] of the ] bullet 3 and table column 2 example 1. Any proposal for modification to the guideline should be posted at its talk page.-->]], while each of the 338 members of the House of Commons – called ] (MPs) – represents an ], commonly referred to as a ''riding'', and are elected by Canadian voters residing in the riding. The governor general<!--UNCAPITALIZED because it is preceded by modifier "The", per ] bullet 3 and table column 2 example 1. Any proposal for modification to the guideline should be posted at its talk page.--> also summons and calls together the House of Commons, and may ] or ], in order to either end a ] or ]. The governor general also delivers the ] at the opening of each new Parliament (the monarch occasionally has done so, instead of the governor general, when visiting Canada). | |||

| ==History== | |||

| The ], summoned by Governor General ] in November 2021, is the 44th Parliament since ] in 1867. On January 6, 2025, the Parliament was prorogued by Simon following prime minister ]'s request to do so and will remain suspended until March 24.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/prorogue-parliament-canada-meaning-1.7412120|title=Canadian Parliament is prorogued. Here's what that means|publisher= Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC)|website=CBC.ca|last1=Maimann|first1=Kevin|last2=Schmunk|first2=Rhianna|date=January 6, 2025|access-date=January 7, 2025}}</ref> | |||

| After Great Britain conquered it from ] during the ] (]–]), Canada (which then consisted mainly of the modern ]) was governed under the ]. This proclamation was superseded in ] by the ], under which the power to make ordinances was granted to a Governor and Council, both appointed by the British sovereign. In ], the Province of Quebec was divided into the provinces of ] (which later became Ontario) and ] (which later became Quebec), each with an elected ] and an appointed ]. | |||

| ==Composition== | |||

| In ], the British Parliament united Upper and Lower Canada into a new colony, called the ]. A single legislature, consisting of an elected Legislative Assembly and an appointed Legislative Council, was created. The assembly's eighty-four members were equally divided between the former provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, though the latter had a higher population. The British government, through the royally-appointed Governors, still exercised considerable influence over Canadian affairs. This influence was reduced in ], when the province was granted ]. | |||

| The body consists of the ], represented by a ], the ]; an ], the ]; and a ], the ]. Each element has its own officers and organization. Each has a distinct role, but work in conjunction within the ]. This format was inherited from the ] and is a near-identical copy of the ], the greatest differences stemming from situations unique to Canada, such as the impermanent nature of the monarch's residency in the country and the lack of a ] to form the upper chamber. | |||

| ] | |||

| In ], the Parliament of Canada, which had been transferred from ] to ] in ], burnt down. The fire was due to a riot led by the ] that was a consequence of a series of tensions between ]s and ]s, as well as an economic depression. In ], the Parliament was finally moved to ], after a few years of alternating between ] and ]. | |||

| Only those who sit in the House of Commons are usually called ] (MPs); the term is not usually applied to senators (except in legislation, such as the '']''), even though the Senate is a part of Parliament. Though legislatively less powerful, senators take higher positions in the ]. No individual may serve in more than one chamber at the same time. | |||

| The modern-day Parliament of Canada, however, did not come into existence until ]. In that year, the British Parliament passed the ], uniting the Province of Canada (which was separated into ] and ]), ], and ] into a single federation, called the Dominion of Canada. The new Canadian Parliament consisted of the Queen (represented by the Governor General), the Senate and the House of Commons. An important influence was the ], which had just concluded, and had indicated to many Canadians the faults of the federal system as implemented in the ]. In part because of the Civil War, the American model, with relatively powerful states and a less powerful federal government, was rejected. The British North America Act limited the powers of the provinces, providing that all subjects not explicitly delegated to them remain within the authority of the federal Parliament. Yet it gave Provinces unique powers in certain agreed-upon areas of funding, and that division still exists today. | |||

| ===Monarch=== | |||

| The British North America Act 1867 granted the Parliament significant powers, but with several restrictions. Most notably, the British Parliament remained supreme over Canada, and no Canadian act could in any way abrogate a British one. Furthermore, the United Kingdom continued to determine the foreign policy of the entire ]. | |||

| {{Main|Monarchy of Canada#Parliament (King-in-Parliament)}} | |||

| ] ]] | |||

| The sovereign's place in the legislature, formally known as the ],<ref>{{cite book |last=MacLeod |first=Kevin |author-link=Kevin S. MacLeod |title=A Crown of Maples |publisher=Department of Canadian Heritage |isbn=978-1-100-20079-8|page=16 |year=2015 |url = http://canada.pch.gc.ca/DAMAssetPub/DAM-PCH2-Identity-Monarchy/STAGING/texte-text/crnMpls_1445001297279_eng.pdf?WT.contentAuthority=4.4.10 |access-date=16 June 2017}}{{Dead link|date=April 2019 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> is defined by the '']'', and various ].<ref name=CA1867-17/> Neither he nor his viceroy, however, participates in the legislative process save for signifying the King's approval to a bill passed by both houses of Parliament, known as the granting of ], which is necessary for a bill to be enacted as law. All federal bills thus begin with the phrase "Now, therefore, His Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate and House of Commons of Canada, enacts as follows ..."<ref>{{Citation |author=Public Works and Government Services Canada |author-link=Public Works and Government Services Canada |publication-date=13 December 2006 |title=Bill C-43 |series=Preamble |publication-place=Ottawa |publisher=Queen's Printer for Canada |url=http://www2.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?Docid=2604319&file=4 |access-date=19 May 2009 |archive-date=15 June 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090615043308/http://www2.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?Docid=2604319&file=4 |url-status=dead }}</ref> and, as such, ] is immune from acts of Parliament unless expressed otherwise in the act itself.<ref>{{Citation |author= Queen Elizabeth II |author-link=Elizabeth II |publication-date=1985 |title=Interpretation Act |series=§17 |publication-place=Ottawa |publisher=Queen's Printer for Canada |url = http://www.canlii.org/en/ca/laws/stat/rsc-1985-c-i-21/latest/rsc-1985-c-i-21.html |access-date=1 June 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090705082900/http://www.canlii.org/en/ca/laws/stat/rsc-1985-c-i-21/latest/rsc-1985-c-i-21.html |archive-date=5 July 2009 }}</ref> The governor general will normally perform the task of granting Royal Assent, though the monarch may also do so, at the request of either the ] or the viceroy, who may defer assent to the sovereign as per the constitution.<ref></ref> | |||

| As both the monarch and his or her representatives are traditionally barred from the House of Commons, any parliamentary ceremonies in which they are involved take place in the Senate chamber. The upper and lower houses do, however, each contain a ], which indicates the authority of the King-in-Parliament and the privilege granted to that body by him,<ref>{{cite web| url=https://lop.parl.ca/About/Parliament/Education/SearchingForSymbols/SymbolsGallery-e.asp| publisher=]| title=Symbols Gallery| access-date=15 June 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal| last=McDonough| first=John| title=The Maces of the Canadian Provincial and Territorial Legislatures (I)| journal=Canadian Regional Review |volume=2| issue=4|page= 36| publisher=Commonwealth Parliamentary Association |location= Ottawa |year= 1979 |url= http://www.revparl.ca/2/4/02n4_79e.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.revparl.ca/2/4/02n4_79e.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live |issn= 0707-0837 |access-date=19 October 2009}}</ref> both bearing a crown at their apex. The original mace for the Senate was that used in the ] after 1849, while that of the House of Commons was inherited from the ], first used in 1845. Following the ] on 3 February 1916, the ], England, donated a replacement, which is still used today. The temporary mace, made of wood, and used until the new one arrived from the United Kingdom in 1917, is still carried into the Senate each 3 February.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www2.parl.gc.ca/Sites/LOP/Education/CanSymbols/galleries/parliament/hoc_mace-e.asp |last=Library of Parliament |author-link=Library of Parliament |title=About Parliament > Education > Classroom Resources > Canadian Symbols at Parliament > Parliament Hill Symbols > Mace (House of Commons) |publisher=Queen's Printer for Parliament |access-date=19 October 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://archive.today/20120919124424/http://www2.parl.gc.ca/Sites/LOP/Education/CanSymbols/galleries/parliament/hoc_mace-e.asp |archive-date=19 September 2012 }}</ref> The Senate's 1.6-metre-long mace comprises brass and gold. The Senate may not sit if its mace is not in the chamber; it typically sits on the table with the crown facing the throne,<ref name=SenatePP>{{Citation | |||

| Greater autonomy was granted by the British Parliament's ]. Though the Statute allowed the Parliament of Canada to repeal or amend British laws (with respect to their application in Canada), it did not permit the abrogation of Canada's constitution, including the British North America Acts. Hence, whenever a constitutional amendment was sought by the Canadian Parliament, the enactment of a British law became necessary. Still, the Parliament of the United Kingdom did not unilaterally impose amendments on the Canadian federation, only acting when requested to do so by the Canadian Parliament. The Parliament of Canada was granted limited power to amend the constitution by a British Act of Parliament in ], but it was not permitted to affect the powers of provincial governments, the official positions of the English and French languages, or the five-year term of Parliament. | |||

| | author = Senate of Canada | |||

| | author-link = Senate of Canada | |||

| | title = Senate Procedure in Practice | |||

| | publication-place = Ottawa | |||

| | publisher = Queen's Printer for Canada | |||

| | date = June 2015 | |||

| | url = https://sencanada.ca/media/93509/spip-psep-full-complet-e.pdf | |||

| | access-date = 2020-03-10 | |||

| | postscript = . | |||

| }}</ref>{{rp|55}} though it may, during certain ceremonies, be held by the mace bearer, standing adjacent to the governor general or monarch in the Senate.{{r|SenatePP|p=51}} | |||

| Members of the two houses of Parliament must also express their loyalty to the sovereign and defer to his authority, as the ] must be sworn by all new parliamentarians before they may take their seats. Further, the ] is formally called ], to signify that, though they may be opposed to the incumbent Cabinet's policies, they remain dedicated to the apolitical Crown.<ref>{{cite book| last=Marleau| first=Robert| author2=Montpetit, Camille| title=House of Commons Procedure and Practice| publisher=Queen's Printer for Canada| year=2000| location=Ottawa| id=1. Parliamentary Institutions > Institutional Framework > The Opposition| url=http://www2.parl.gc.ca/MarleauMontpetit/DocumentViewer.aspx?DocId=1001&Sec=Ch01&Seq=3&Lang=E| isbn=2-89461-378-4| access-date=19 October 2009| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121008170948/http://www.parl.gc.ca/MarleauMontpetit/DocumentViewer.aspx?DocId=1001&Lang=E&Sec=Ch01&Seq=3| archive-date=8 October 2012| url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{Citation|first=Gerald |last=Schmitz |title=The Opposition in a Parliamentary System |date=December 1988 |place=Ottawa |publisher=Queen's Printer for Canada |url=http://www.parl.gc.ca/information/library/PRBpubs/bp47-e.htm |access-date=21 May 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090425171259/http://www.parl.gc.ca/information/library/PRBpubs/bp47-e.htm |archive-date=25 April 2009 }}</ref> | |||

| The Parliament of Canada last requested the Parliament of the United Kingdom to enact a constitutional amendment in ], when the ] was requested and passed. The Act ended the power of the British Parliament to legislate for Canada, and the authority to amend the constitution was transferred to Canadian legislative authorities. Most amendments require the consent of the Canadian Senate, the Canadian House of Commons, and the ] of two-thirds of the provinces representing a majority of the population. The unanimous consent of provincial Legislative Assemblies is required for certain amendments, including those affecting the Queen, the Governor General, provincial Lieutenant Governors, the official positions of the English and French languages, the ], and the amending formulas themselves. | |||

| == |

=== Senate === | ||

| {{Main|Senate of Canada}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] is decorated in green, and that of the Senate in red, following the tradition of the British Parliament.]] | |||

| The ] of the Parliament of Canada, the Senate ({{langx|fr|Sénat|italic=unset}}), is a group of 105 individuals appointed by the governor general on the advice of the prime minister;<ref></ref> all those appointed must, per the constitution, be a minimum of 30 years old, be a subject of the monarch, and own property with a net worth of at least $4,000, in addition to owning land worth no less than $4,000 within the province the candidate seeks to represent.<ref></ref> Senators served for life until 1965, when a constitutional amendment imposed a mandatory retirement age of 75. Senators may, however, resign their seats prior to that mark, and can lose their position should they fail to attend two consecutive sessions of Parliament. | |||

| The ] (in French ''la Reine'') (presently ]) is one of the three components of Parliament. The monarch's functions are customarily delegated to the Governor General (presently ]), who is appointed by the Monarch on the advice of the Canadian Prime Minister. Governors General serve ], but normally for a term of approximately five years. Though the Queen and Governor General have vast powers in theory, they rarely exercise them in practice. Rather, both perform ceremonial duties, most usually exercising political powers only on the advice of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. | |||

| The principle underlying the Senate's composition is equality amongst Canada's geographic regions (called Divisions in the Constitution): 24 for ], 24 for ], 24 for the ] (10 for ], 10 for ], and four for ]), and 24 for the ] (six each for ], ], ], and ]).<ref></ref> Additionally, senators are appointed from two geographic areas not part of any senatorial division. ] (since 1949 the "newest" province, although ]), is represented by six senators. Since 1975 each of Canada's territories is represented by 1 senator—the ], ], and (since its formation in 1999) ]. An additional 4 or 8 senators may be appointed by the governor general, provided the approval of the King is secured and the four divisions are equally represented. This power has been employed once since 1867: to ensure the passage of the bill establishing the ], Prime Minister ] advised Queen Elizabeth II to appoint extra senators in 1990. This results in a temporary maximum number of senators of 113, which must through attrition return to its normal number of 105. | |||

| The entirely appointed Upper House of Canada's Parliament is the Senate (in French, ''le Sénat''). Though they are meant to represent the provinces, senators are selected by the Prime Minister, and are formally appointed by the Governor General. To become a senator, one must be at least thirty years old, must be a subject of the Queen, and must own property with a net worth of at least $4,000. The senator must reside and own land worth at least $4,000 in the province he or she is meant to represent. Senators formerly served for life, but, since ], leave the Senate at the age of seventy-five. Senators may resign their seats, and lose their positions if they fail to attend two consecutive sessions of Parliament. | |||

| ===House of Commons=== | |||

| The constitution groups Canada's provinces into four divisions, each with an equal number of senators: twenty-four for ]; twenty-four for ]; twenty-four for the ] (ten for ], ten for ], and four for ]); and twenty-four for the ] (six each for ], ], ], and ]). ], which became a province only in ], is not assigned to any division, and is represented by six senators. Furthermore, the three territories (the ], the ], and ]) are allocated one senator each. Hence, the Senate normally consists of 105 members. The Governor General, however, may temporarily increase the size of the Senate by summoning an additional four or eight senators, provided the approval of the Queen is secured. Canada's four "divisions" must remain equally represented. This | |||

| {{Main|House of Commons of Canada}} | |||

| power has only been employed once in Canadian history: on the advice of Prime Minister ] in ] to ensure the passage of a bill creating the ]. There may be no more than eight additional senators at any time (making the maximum size of the Senate 113). | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The elected component of the Canadian Parliament is the House of Commons ({{langx|fr|Chambre des communes|italic=unset}}), with each member chosen by a plurality of voters in each of the country's federal ], or ridings. To run for one of the 338 seats in the ], an individual must be at least 18 years old. Each member holds office until Parliament is dissolved, after which they may seek re-election. The ridings are regularly reorganized according to the results of each decennial national ];<ref name=ElizabethIII.2>{{Citation |author = Queen Elizabeth II |author-link=Elizabeth II |publication-date=4 March 1986| title=Constitution Act, 1985 (Representation) |at=I.2 |publication-place=Ottawa |publisher=Queen's Printer for Canada |url=http://www.solon.org/Constitutions/Canada/English/ca_1985.html |access-date=19 October 2009 }}</ref> however, the "senatorial clause" of the ''Constitution Act, 1867'' guarantees each province at least as many MPs as it has senators,<ref></ref> and the "grandfather clause" permits each province as many MPs as it had in either 1976 or 1985.<ref name=ElizabethIII.2/> The existence of this legislation has pushed the size of the House of Commons above the required minimum of 282 seats. | |||

| ==Jurisdiction== | |||

| Parliament's democratically elected component is the House of Commons (in French, ''la Chambre des communes''). Each member represents a single electoral district (or "riding"), and is elected in that district by the simple ]. They must be Canadian citizens and at least 18 years old. Members hold office until they resign or Parliament is dissolved, and can be reelected any number of times. | |||

| The powers of the Parliament of Canada are limited by the constitution, which divides legislative abilities between the federal and ]; in general, provincial ] may only pass laws relating to topics explicitly reserved for them by the constitution (such as education, provincial officers, municipal government, charitable institutions, and "matters of a merely local or private nature")<ref></ref> while any matter not under the exclusive authority of the provincial legislatures is within the scope of the federal Parliament's power. Thus, Parliament alone can pass laws relating to, among other things, the postal service, census, ], navigation and shipping, fishing, currency, banking, weights and measures, bankruptcy, copyrights, patents, ], and ].<ref></ref> In some cases, however, the jurisdictions of the federal and provincial parliaments may be more vague. For instance, the federal parliament regulates marriage and divorce in general, but the solemnization of marriage is regulated only by the provincial legislatures. Other examples include the powers of both the federal and provincial parliaments to impose taxes, borrow money, punish crimes, and regulate agriculture. | |||

| The powers of Parliament are also limited by the '']'', though most of its provisions can be overridden by use of the ].<ref>{{Citation |author = Queen Elizabeth II |author-link=Elizabeth II |publication-date=29 March 1982 |title = Constitution Act, 1982 |at=33 |publication-place=Ottawa |publisher=Queen's Printer for Canada |url = http://www.solon.org/Constitutions/Canada/English/ca_1982.html |access-date=20 October 2009 }}</ref> Such clause, however, has never been used by the federal parliament, though it has been employed by some provincial legislatures. Laws violating any part of the constitution are invalid and may be ruled unconstitutional by ]. | |||

| The constitution does not fix the size of the House of Commons, which is re-adjusted every ten years after a ]. The House must consist of at least 282 seats, of which three are reserved for the territories. The remaining 279 seats are assigned to the provinces based on their populations. However, the "senatorial clause" guarantees each province at least as many Members of Parliament as senators. Furthermore, the "grandfather clause" guarantees each province at least as many Members of Parliament as it had in ] or in ]. Because of these two clauses, the size of the House of Commons exceeds the minimum (282). At present, the House includes 308 members. | |||

| ==Officers== | |||

| No individual may serve in more than one House of Parliament. Members of the House of Commons are commonly called "Members of Parliament" or "MPs"; this term is never applied to senators, even though the Senate is a part of Parliament. Though less powerful, senators occupy higher positions than Members of Parliament in the ]. | |||

| Each of Parliament's two chambers is presided over by a ]; ] is a member appointed by the governor general on the advice of the prime minister, while the ] is a member of Parliament, who is elected by the other members of that body. In general, the powers of the latter are greater than those of the former. Following the British model, the upper chamber is essentially self-regulating, but the lower chamber is controlled by the chair, in a majoritarian model that gives great power and authority to the chair. In 1991, however, the powers of the ] were expanded, which reorganized the balance of power to be closer to the framework of the Commons.{{citation needed|date=May 2021}} | |||

| ], before the thrones in the Senate chamber, 2009]] | |||

| The ] bullet 3 and table column 2 example 1. Any proposal for modification to the guideline should be posted at its talk page.-->of the black rod <!--the full job title is "Usher of the Black Rod. If "usher" isn't capitalised, then neither is "black rod"--> of the Senate of Canada]] is the most senior protocol position in Parliament, being the personal messenger to the legislature of the sovereign and governor general. The usher is also a floor officer of the Senate responsible for security in that chamber, as well as for protocol, administrative, and logistical details of important events taking place on Parliament Hill,<ref>{{cite web |url = http://www.parl.gc.ca/information/about/people/senate/leaders_officers/BlackRod-e.htm |last=Library of Parliament |author-link=Library of Parliament |title=usher of the black rod in the Senate |publisher=Queen's Printer for Canada |access-date=19 October 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090816194103/http://www.parl.gc.ca/information/about/people/senate/leaders_officers/BlackRod-e.htm |archive-date=16 August 2009 }}</ref> such as the ], Royal Assent ceremonies, ]s, or the investiture of a new governor general.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Queen Elizabeth II |author-link=Elizabeth II |title=Notice of Vacancy, usher of the black rod |journal=Canada Gazette |volume=142 |issue=2 |page=74 |publisher=Queen's Printer for Canada |location=Ottawa |date=12 January 2008 |url=http://www.gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p1/2008/2008-01-12/pdf/g1-14202.pdf |access-date=26 January 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130522212808/http://www.gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p1/2008/2008-01-12/pdf/g1-14202.pdf |archive-date=22 May 2013 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| Other officers of Parliament include the ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. These individuals are appointed by either one or both houses, to which they report through the ] of that house. They are sometimes referred to as ''Agents of Parliament''.<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.parl.gc.ca/parlinfo/compilations/officersandofficials/OfficersOfParliament.aspx| title=Officers and Officials of Parliament| publisher=Queen's Printer for Canada| access-date=27 May 2011| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110430153007/http://www.parl.gc.ca/parlinfo/compilations/officersandofficials/OfficersOfParliament.aspx| archive-date=30 April 2011| url-status=dead}}</ref> Another key official is the ], a position established in 1871 under the ''Library of Parliament Act'', charged with directing the ]. | |||

| ==Procedure== | |||

| ==Term== | |||

| Each of the two Houses is presided over by a Speaker. The ] is a senator selected by the Prime Minister and formally appointed by the Governor General. The ], on the other hand, is elected by his fellow members. In general, the powers of the Speaker of the House are much greater than the powers of the Speaker of the Senate. Following the British model, the upper House is more or less self-regulating, whereas the Lower House is controlled from the chair. In ], however, the powers of the Speaker of the Senate were expanded, moving his or her position closer to that of the Speaker of the House. | |||

| The ''Constitution Act, 1867'', outlines that the governor general alone is responsible for summoning Parliament, though it remains the monarch's ] to ] and ] the legislature, after which the ] for a ] are usually ] at ]. Upon completion of the election, the governor general, on the advice of the prime minister, then issues a royal ] summoning Parliament to assemble. On the date given, new MPs are sworn in and then are, along with returning MPs, called to the Senate, where they are instructed to elect their speaker and return to the House of Commons to do so before adjourning.{{r|SenatePP|p=42}}] | |||

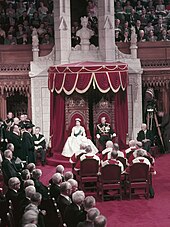

| The new parliamentary session is marked by the ], a ceremony where a range of topics can be addressed in a ] given by the monarch, the governor general, or a royal delegate.{{NoteTag|On 1 September 1919, Edward, Prince of Wales (later King ]) read the Speech From the Throne at the opening of the third session of the ].|name=Open}} The usher of the black rod invites MPs to these events,<ref>{{cite web |url = http://www.speech.gc.ca/eng/media.asp?id=1367 |author=Government of Canada |author-link=Government of Canada |title=Speech From the Throne > Frequently Asked Questions |publisher=Queen's Printer for Canada |access-date=4 June 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100309072021/http://www.speech.gc.ca/eng/media.asp?id=1367 |archive-date=9 March 2010 }}</ref> knocking on the doors of the lower house that have been slammed shut<ref>{{cite web |url = http://www2.parl.gc.ca/Parlinfo/compilations/OfficersAndOfficials/ProceduralOfficersAndSeniorOfficials_Senate.aspx |last=Library of Parliament |author-link=Library of Parliament |title=Parliament > Officers and Officials of Parliament > Procedural Officers and Senior Officials > Senate |publisher=Queen's Printer for Canada |access-date=19 May 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20081201130735/http://www2.parl.gc.ca/Parlinfo/compilations/OfficersAndOfficials/ProceduralOfficersAndSeniorOfficials_Senate.aspx |archive-date=1 December 2008 }}</ref>—a symbolic arrangement designed to illustrate the Commons' right to deny entry to anyone, including even the monarch (but with an exception for royal messengers).<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.royal.gov.uk/RoyalEventsandCeremonies/StateOpeningofParliament/State%20Opening%20of%20Parliament.aspx |author=Royal Household | title=Royal events and ceremonies > State Opening of Parliament | publisher=Queen's Printer | access-date=13 October 2012 }}</ref> Once the MPs are gathered behind the Bar of the Senate—save for the prime minister, the only MP permitted into the Senate proper to sit near the throne dais—the House of Commons speaker presents to the monarch or governor general, and formally claims the rights and privileges of the House of Commons; and then the speaker of the Senate, on behalf of the Crown, replies in acknowledgement after the sovereign or viceroy takes their seat on the throne.{{r|SenatePP|p=42}} The speech is then read aloud. It can outline the program of the ] for the upcoming legislative session, as well as other matters chosen by the speaker. | |||

| A ] lasts until a prorogation, after which, without ceremony, both chambers of the legislature cease all legislative business until the governor general issues another proclamation calling for a new session to begin; except for the election of a speaker for the House of Commons and his or her claiming of that house's privileges, the same procedures for the opening of Parliament are again followed. After a number of such sessions—having ranged from one to seven{{r|SenatePP|p=45}}—a Parliament comes to an end via ], and a general election typically follows. Subject to the governor general's discretion, general elections are held four years after the previous on the third Monday in October or, on the recommendation of the ], the following Tuesday or Monday. The governor general may dissolve Parliament and call a general election outside of these fixed dates, conventionally on the advice of the prime minister, which may be preceded by a successful ]. The timing of such dissolutions may be politically motivated.<ref>{{cite web |title=Canada Elections Act |url = http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/E-2.01/page-9.html#h-27 |website=Justice Laws Website |access-date=17 July 2017 |at = Part 5 }}</ref><ref>{{citation |author= Queen Elizabeth II |author-link=Elizabeth II |title=Canada Elections Act |url = http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/E-2.01/page-23.html#h-24 |at=56.1.(2) |date=12 July 2008 |publisher=Queen's Printer for Canada |access-date=3 May 2011 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Dissolution of Parliament – Compendium of Procedure – House of Commons |url = https://www.ourcommons.ca/About/Compendium/ParliamentaryCycle/c_d_dissolutionparliament-e.htm |access-date=18 July 2017 }}</ref> | |||

| The constitution establishes the ]s of both Houses. The quorum is fifteen senators in the Upper House and twenty members in the Lower House. In each House, the Speaker is counted when ascertaining the presence of a quorum. | |||

| ==Procedure== | |||

| Both Houses may determine motions by voice vote; the presiding officer puts the question, and, after listening to shouts of "Yea" and "Nay" from the members, announces which side is victorious. The decision of the Speaker is final, unless a recorded vote is demanded by members of the House (at least two senators or at least five members of the House of Commons). Members in both Houses vote by rising in their places to be counted. In the Senate, the Speaker is allowed to vote (though he or she does not often do so, in the interests of maintaining impartiality), and if there is no majority, the motion is defeated. In the House, however, the Speaker may not vote, unless there is a tie. Moreover, the Speaker customarily votes in favour of the ]. Although it is parliamentary tradition for the Speaker to vote for the status quo, he is bound only by custom. For example, during the 2005 budget vote, which was considered a vote of confidence, the Speaker of the House cast the tie-breaking vote and voted in favour of the budget. | |||

| Both houses determine ] by ]; the presiding officer puts the question and, after listening to shouts of "yea" and "nay" from the members, announces which side is victorious. This decision by the Speaker is final, unless a recorded vote is demanded by members—requiring at least two in the Senate and five in the House of Commons. Members of both houses vote by rising in their places to be counted; the speaker of the Senate is permitted to vote on a motion or bill—though does so irregularly, in the interest of impartiality—and, if there is no majority, the motion is defeated. In the Commons, however, the speaker cannot vote, unless to break a tie. The speaker customarily votes in favour of the ]. The constitution establishes the ]s to be 15 senators in the upper house and 20 members in the lower house, the speaker of each body being counted within the tally. | |||

| Voting can thus take three possible forms: whenever possible, leaving the matter open for future consideration and allowing for further discussion by the house; when no further discussion is possible, taking into account that the matter could somehow be brought back in future and be decided by a majority in the house; or, leaving a bill in its existing form rather than having it amended. For example, during the vote on the ], which was considered a ], the speaker of the House of Commons cast the tie-breaking vote during the ], moving in favour of the budget and allowing its passage. If the vote on the ] had again been tied, the speaker would have been expected to vote against the bill, bringing down the government. | |||

| ==Term== | |||

| <!-- Unsourced image removed: ] --> | |||

| After a general election, the Governor General (acting on the advice of the Prime Minister) formally issues a proclamation summoning Parliament. On the day indicated by the proclamation, the members of the two Houses assemble in their respective chambers. The ceremony observed at this time is similar to that observed in the British Parliament. Having assembled, the Commons are summoned to the Senate Chamber, where they are instructed to elect a Speaker. The Commons return to their chamber, elect a Speaker, and then adjourn. | |||

| Simultaneous ] for both official languages, ] and ], is provided at all times during sessions of both houses. | |||

| On the next day, the formal ] occurs. The ], an official of the Senate, formally summons the Commons to the Senate. The Commons proceeds to the Bar of the Senate, but do not enter the Senate Chamber itself. The Speaker of the House then presents himself to the Monarch or the Governor General (who takes his or her seat on the Throne in the Senate Chamber), formally claiming the rights and privileges of the House of Commons. The Speaker of the Senate then replies, acknowledging, on the behalf of the Governor General, the privileges of the House of Commons. With the members of the House of Commons remaining at the Bar, and with the senators seated in the Senate Chamber, the Monarch or the Governor General (seated on the Throne) delivers an address known as the ]. In it, he or she outlines the program of the Government for the upcoming legislative session. The speech is actually written by the ministers and not the Crown. | |||

| ==Legislative functions== | |||

| A session of Parliament, having been formally opened, continues until a "prorogation" brings about its conclusion. Prorogation is generally achieved by a proclamation of the Governor General, again issued on the advice of the Prime Minister. No special prorogation ceremony, however, needs to be observed. Having been prorogued, each House does not conduct any further business until the Governor General issues another proclamation for a new session. The procedures described above are used at the beginning of such a session, except that a new Speaker need not be elected and the privileges of the House of Commons need not be claimed again. | |||

| Laws, known in their draft form as ]s, may be introduced by any member of either house. However, most bills originate in the House of Commons, of which most are put forward by ], making them government bills, as opposed to ] or private senators' bills, which are launched by MPs and senators, respectively, who are not in cabinet. Draft legislation may also be categorized as public bills, if they apply to the general public, or ], if they concern a particular person or limited group of people. Each bill then goes through a series of stages in each chamber, beginning with the ]. It is not, however, until the bill's ] that the general principles of the proposed law are debated; though rejection is a possibility, such is not common for government bills. | |||

| Next, the bill is sent by the house where it is being debated to one of several committees. The Standing Orders outline the general mandate for all committees, allowing them to review: bills as they pertain to relevant departments; the program and policy plans, as well as the projected expenditures, and the effectiveness of the implementation thereof, for the same departments; and the analysis of the performance of those departments.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www2.parl.gc.ca/procedure-book-livre/Document.aspx?Language=E&Mode=1&sbdid=DC42FA65-ADAA-426C-8763-C9B4F52A1277&sbpid=085013AB-4B16-4B34-8E4C-A5B5C98818C9#C1254467-CDA6-4DB2-8382-DDFFECD6B281 | author=Parliament of Canada | title=House of Commons Procedure and Practice > 20. Committees > Types of Committees and Mandates | publisher=Queen's Printer for Canada | access-date=6 February 2011 | archive-date=9 May 2013 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130509120250/http://www.parl.gc.ca/procedure-book-livre/Document.aspx?Language=E&Mode=1&sbdid=DC42FA65-ADAA-426C-8763-C9B4F52A1277&sbpid=085013AB-4B16-4B34-8E4C-A5B5C98818C9#C1254467-CDA6-4DB2-8382-DDFFECD6B281 | url-status=dead }}</ref> Most often, bills end up before a ], which is a body of members or senators who specialize in a particular subject (such as ]), and who may hear testimony from ministers and experts, debate the bill, and recommend amendments. The bill may also be committed to the ], a body consisting of, as the name suggests, all the members of the chamber in question. Finally, the bill could be referred to an ''ad hoc'' committee established solely to review the piece of legislation in question. Each chamber has their own procedure for dealing with this, with the Senate establishing special committees that function like most other committees, and the House of Commons establishing legislative committees, the chair of the latter being appointed by the speaker of the House of Commons, and is normally one of his deputies. Whichever committee is used, any amendments proposed by the committee are considered by the whole house in the report stage. Furthermore, additional amendments not proposed by the committee may also be made. | |||

| Each Parliament, after a number of sessions, comes to an end, usually by a "dissolution." A dissolution is effected by the Governor General, who, however, acts on the advice of the Prime Minister. Because a general election follows, the timing of a dissolution is usually politically motivated, with the Prime Minister selecting the moment most advantageous to his or her political party. A dissolution, however, may also become necessary if the Prime Minister's support in the House of Commons collapses. Dissolution is not the only method by which a Parliament may be brought to an end: parliamentary terms expire five years after they begin. In the history of Canada, however, no Parliament has been allowed to "expire". | |||

| After the report stage (or, if the committee made no amendments to the bill, immediately after the committee stage), the final phase of the bill—the ]—occurs, at which time further amendments are not permitted in the House of Commons, but are allowed in the Senate. If it passes the third reading, the bill is sent to the other house of Parliament, where it passes through the same stages;{{NoteTag|Although rare, at times the incorrect version of a bill is transmitted between houses (i.e. not what passed third reading)—causing procedural problems, especially if not caught quickly, allowing the other house to advance the incorrect bill through multiple stages. For the last two occurrences (2014 and 2001), see {{cite news |author=Jordan Press |title=House of Commons to Correct Errors in Crime Bill it Sent to Senate |date=2014-08-28 |url = https://ottawacitizen.com/news/national/house-of-commons-to-correct-errors-in-crime-bill-it-sent-to-senate |newspaper=] |at=National News |access-date=2019-06-07 }}.}} amendments made by the second chamber require the assent of the original house in order to stand part of the final bill. If one house passes amendments that the other will not agree to, and the two houses cannot resolve their disagreements, the bill fails. | |||

| After each Parliament ends, whether by dissolution or by effluxion of time, members of the House of Commons face general elections, but senators continue in office. Each body that assembles following an election is considered a separate Parliament; thus, the body which assembled in ] is known as the ]. | |||

| ], with ], grants ] to bills in the Senate chamber, 1939]] | |||

| Once the bill is passed in identical form by both houses, it is presented for ]; in theory, the governor general has three options: grant Royal Assent, thereby making the bill into law; withhold Royal Assent, thereby vetoing the bill; or reserve the bill for the signification of the King's ], which allows the sovereign to personally grant or withhold assent. If the governor general does grant Royal Assent, the monarch may, within two years, disallow the bill, thus annulling the law in question. In the federal sphere, no bill has ever been denied royal approval. | |||

| In conformity with the British model, only the House of Commons may originate bills for the imposition of taxes or for the appropriation of Crown funds. The constitutional amendment procedure does make provision for the Commons overcoming an otherwise-required Senate resolution in most cases. Otherwise, the theoretical power of both houses over bills is equal, with the assent of each being required for passage. In practice, however, the House of Commons is dominant, with the Senate rarely exercising its powers in a way that opposes the will of the democratically elected house. | |||

| ==Legislative functions== | |||

| Laws, in draft form known as bills, may be introduced by any member of either House, but are most often introduced by Ministers of the Crown, and are known as Government Bills. Bills introduced by members who are not Ministers are known as Private Members' Bills (in the case of the House of Commons) or as Private Senators' Bills (in the case of the Senate). Bills may also be categorised as Public Bills (if they apply to the general public) or as Private Bills (if they particularly concern a person or a limited group of persons). | |||

| ==Relationship with the executive== | |||

| Each bill goes through a number of stages in each House. The first stage, known as the ], is purely formal. At the ensuing ], the general principles of the bill are debated; though a rejection is possible, it is not common in the case of Government Bills. | |||

| The ] consists of the ], which is a collection of ministers of the Crown appointed by the governor general to direct the use of ]. Per the tenets of ], these individuals are almost always drawn from Parliament, and are predominantly from the House of Commons, the only body to which ministers are held accountable, typically during ], wherein ministers are obliged to answer questions posed by members of the opposition. Hence, the person who can command the confidence of the lower chamber—usually the leader of the party with the most seats therein—is typically appointed as prime minister. Should that person not hold a seat in the House of Commons, the prime minister will, by convention, seek election to one at the earliest possible opportunity; frequently, in such situations, a junior member of Parliament who holds a ] will resign to allow the prime minister to run for that riding in a ]. If no party holds a majority, it is customary for the governor general to summon a ] or ], depending on which the commons will support. | |||

| The lower house may attempt to bring down the government by either rejecting a motion of ]—generally initiated by a minister to reinforce the Cabinet's support in the commons—or by passing a motion of no confidence—introduced by the opposition to display its distrust of the Cabinet. Important bills that form part of the government's agenda will usually be considered matters of confidence; the budget is always a matter of confidence. Where a government has lost the confidence of the House of Commons, the prime minister is obliged to either resign (allowing the governor general to appoint the ] to the office) or seek the dissolution of Parliament and the call of a general election. A precedent, however, was set in 1968, when the government of ] unexpectedly lost a confidence vote but was allowed to remain in power with the mutual consent of the leaders of the other parties. | |||

| Next, the bill is sent by the House in question to one of several different committees. Most often, the bill is committed to a Standing Committee, a body of members or senators which specialises in a particular subject (such as foreign affairs). The committee may examine witnesses, Ministers, and experts, debate the bill, and recommend amendments. The bill may also be committed to the Committee of the Whole, a body which consists, as the name suggests, of all the members of the House in question. Finally, the bill could be referred to an ''ad hoc'' committee established solely to review the piece of legislation in question. Each chamber has their own procedure for dealing with this, with the Senate establishing special committees, which function like most other committees, and the House of Commons establishing Legislative Committees. A Legislative Committee is an ''ad hoc'' committee established to consider a piece of legislation, but the Chair is appointed by the Speaker of the House of Commons, and is normally one of his deputies. The Senate has no procedure for Legislative Committees. Whichever committee is used, any amendments proposed by the committee are considered by the whole House in the Report Stage. Furthermore, additional amendments not proposed by the committee may also be made. | |||

| In practice, the House of Commons' scrutiny of the government is quite weak in comparison to the equivalent chamber in other countries using the ]. With the ] used in parliamentary elections tending to provide the governing party with a large majority, and a party system that gives leaders strict control over their caucus (to the point that MPs may be expelled from their parties for voting against the instructions of party leaders), there is often limited need to compromise with other parties. Additionally, Canada has fewer MPs, a higher turnover rate of MPs after each election, and an Americanized system for selecting political party leaders, leaving them accountable to the party membership rather than caucus, as is the case in the United Kingdom;<ref>{{Citation | last=Foot |first=Richard | title = Only in Canada: Harper's prorogation is a Canadian thing |newspaper=National Post | date=15 January 2010 | url = https://nationalpost.com/story.html?id=2446705 | access-date=16 January 2010 | url-status=dead | archive-url = https://archive.today/20100118165801/http://www.nationalpost.com/story.html?id=2446705 | archive-date=18 January 2010 }}</ref> John Robson of the ''National Post'' opined that Canada's parliament had become a body akin to the ], "its sole and ceremonial role to confirm the executive in power."<ref>{{cite news | url = http://news.nationalpost.com/full-comment/john-robson-trudeaus-promise-of-electoral-reform-is-menacing| last=Robson| first=John| title=Trudeau's menacing promise of electoral reform| date=2 November 2015| newspaper=National Post| access-date=5 November 2015}}</ref> | |||

| After the Report Stage (or, if the committee made no amendments to the bill, immediately after the Committee Stage), the final stage of the bill—the ]—occurs. Further amendments are not permitted in the House of Commons, but are allowed in the Senate. If it passes the third reading, the bill is sent to the other House, where it passes through the same stages. Amendments made by the second House require the assent of the original House in order to stand part of the final bill. If, however, one House passes amendments that the other will not agree to, and the two Houses cannot resolve their disagreements, the bill fails. | |||

| At the end of the 20th century and into the 21st, analysts—such as ], ], and ]—argued that both Parliament and the Cabinet had become eclipsed by prime ministerial power.<ref>{{cite book| last=Brooks| first=Stephen| title=Canadian Democracy: An Introduction| publisher=Oxford University Press| year=2007| location=Don Mills| page=| edition=5th| isbn=978-0-19-543103-2| url=https://archive.org/details/canadiandemocrac0006broo/page/258}}</ref> Thus, defeats of majority governments on issues of confidence are very rare. In contrast, a minority government is more volatile, and is more likely to fall due to loss of confidence. The last prime ministers to lose confidence votes were ] in 2011, ] in 2005 and ] in 1979, all involving minority governments. The passage of the '']'' and resulting changes to the '']'', in 2015, were a response to this trend and an attempt to increase the power and independence of MPs.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|last=Mas|first=Susana|date=2015-10-27|title=Michael Chong urges MPs to 'reclaim their influence' as Reform Act takes effect|url=https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/michael-chong-reform-act-1.3289892|website=CBC News}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|last=Wherry|first=Aaron|date=2013-12-02|title=Explainer: Who is Michael Chong? And what does he want to do with our Parliament?|url=https://www.macleans.ca/news/canada/who-is-michael-chong-and-what-does-he-want-to-do-with-our-parliament/|access-date=2022-02-03|website=Macleans.ca|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last=Editorial Board |title=The way Conservative MPs – not just their leader – ousted Derek Sloan shows the value of the Reform Act |url=https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/editorials/article-the-way-conservative-mps-not-just-their-leader-ousted-derek-sloan/ |date=January 21, 2021 |work=] |access-date=February 8, 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last=O'Malley |first=Kady |title=Process Nerd: So, how's the Reform Act working so far? |url=https://ipolitics.ca/2022/02/02/process-nerd-so-hows-the-reform-act-working-so-far/ |date=February 2, 2022 |work=] |access-date=February 8, 2022}}</ref> | |||

| Finally, if the bill is passed in identical form by both Houses, it is presented for the ]. In theory, the Governor General has three options: he or she may grant the Royal Assent (making the bill law), withhold the Royal Assent (vetoing the bill) or reserve the bill for the Signification of the Queen's Pleasure (allowing the Sovereign to personally grant or withhold Assent). If the Governor General does grant the Royal Assent, the Sovereign may, within two years, "disallow" the bill, thereby annulling the law in question. By modern constitutional convention, however, the Royal Assent is ''always'' granted, and bills are never disallowed. | |||

| ==Privileges== | |||

| In conformity with the British model, only the House of Commons may originate bills for the imposition of taxes or for the appropriation of public funds. Otherwise, the theoretical power of both Houses over bills is equal, with the assent of each being required for passage. In practice, however, the House of Commons is the dominant chamber of Parliament, with the Senate rarely exercising its powers in a way that opposes the will of the democratically elected House. | |||

| Parliament possesses a number of privileges, collectively and accordingly known as ], each house being the guardian and administrator of its own set of rights. Parliament itself determines the extent of parliamentary privilege, each house overseeing its own affairs, but the constitution bars it from conferring any "exceeding those at the passing of such an Act held, enjoyed, and exercised by the Commons... and by the Members thereof."<ref></ref> | |||

| The foremost dispensation held by both houses of Parliament is that of ] in debate; nothing said within the chambers may be questioned by any court or other institution outside of Parliament. In particular, a member of either house cannot be sued for ] based on words uttered in the course of parliamentary proceedings, the only restraint on debate being set by the standing orders of each house. Further, MPs and senators are immune to arrest in civil (but not criminal) cases, from jury service and attendance in courts as witnesses. They may, however, be disciplined by their colleagues for breach of the rules, including ]—disobedience of its authority; for example, giving false testimony before a parliamentary committee—and breaches of its own privileges. | |||

| ==Relationship with the Government== | |||

| ], ].]] | |||

| The Canadian Government is answerable to the Lower House of Parliament, the House of Commons. However, neither the Prime Minister nor members of the Government are elected by the House of Commons. Instead, the Governor General requests the person most likely to command the support of a majority of the House of Commons (usually the leader of the party with the greatest number of seats in that House) to form a government. If no party holds a majority, it is customary to appoint a ] rather than a ]. The Prime Minister then selects the members of the Cabinet, who are then formally appointed by the Governor General. | |||

| The ], on 15 April 2008, granted the Parliament of Canada, as an institution, a ] composed of symbols of the three elements of Parliament: the ] of the ] with the maces of the House of Commons and Senate crossed behind.<ref>{{cite web| url=http://archive.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1284&ProjectElementID=4487| last=Canadian Heraldic Authority| author-link=Canadian Heraldic Authority| title=Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada > Parliament of Canada| publisher=Queen's Printer for Canada| access-date=8 August 2010}}</ref> | |||

| So that they may be accountable to the Lower House, the Prime Minister and most members of the Cabinet are members of the House of Commons instead of the Senate. If the leader of the largest party is not a member of the House of Commons, then he or she, by constitutional convention, seeks election to that House at the earliest possible opportunity. Normally, a junior member of Parliament who holds a safe seat resigns to allow the Prime Minister to enter the House of Commons. | |||

| The budget for the Parliament of Canada for the 2010 ] was ]583,567,000.<ref>{{Cite news| last=Vongdougngchanh| first=Bea| title=Parliament's budget boosted to $583,567,000 this year| newspaper=The Hill Times| location=Ottawa| date=8 March 2010| url=http://hilltimes.com/page/view/legislation-03-08-2010| access-date=6 January 2011| url-status=dead| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110105032617/http://www.hilltimes.com/page/view/legislation-03-08-2010| archive-date=5 January 2011}}</ref> | |||

| The House of Commons, not the Senate, is the ] of Parliament, meaning that the Government is answerable to it alone. It controls the executive by passing or rejecting its Bills and by forcing Ministers of the Crown to answer for their actions, for example during "]," when the Ministers are obliged to answer questions posed by members. The Lower House may attempt to bring down the Government by rejecting a ] or by passing a ]. Confidence Motions are generally originated by the Government in order to reinforce its support in the House, whilst No Confidence Motions are introduced by the Opposition. Important bills that form part of the Government's agenda are generally considered matters of confidence. Furthermore, the confidence of the House of Commons is deemed to have been withdrawn if that House "withdraws Supply," that is, rejects the Budget. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Where a Government has lost the confidence of the House of Commons, the Prime Minister is obliged to either resign (allowing the Governor General to appoint the ] to the office), or seek the dissolution of Parliament and a new general election. A precedent, however, was set in ], when the Government of ] unexpectedly lost a confidence vote, but was allowed to remain in power with the mutual consent of the leaders of the other parties. Though the Governor General is theoretically permitted to refuse to dissolve Parliament, it is highly improbable that he or she would do so. {{further|]}} | |||

| Following the cession of ] to the ] in the ], Canada was governed according to the ] issued by ] in that same year. To this was added the ], by which the power to make ordinances was granted to a ], both the governor and council being appointed by the British monarch in Westminster, on the advice of his or her ministers there. In 1791, the Province of Quebec was divided into ] and ], each with an elected ], an appointed ], and a governor, mirroring the parliamentary structure in Britain. | |||

| During the ], ] ] to the ] of the ] in ] (now ]). In 1841, the British government united the two Canadas into the ], with a single ] composed of, again, an assembly, council, and governor general; the 84 members of the lower chamber were equally divided among the two former provinces, though Lower Canada had a higher population. The governor still held significant personal influence over Canadian affairs until 1848, when ] was implemented in Canada. | |||

| In practice, the House of Commons' scrutiny of the Government is very weak. Since the First-Past-the-Post electoral system is employed in elections, the governing party tends to enjoy a large majority in the Commons; there is often limited need to compromise with other parties. Modern Canadian political parties are so tightly organised that they leave relatively little room for free action by their MPs. In many cases, MPs may be expelled from their parties for voting against the instructions of party leaders. Thus, defeats of majority governments on issues of confidence are very rare. The last Prime Minister to lose a confidence vote was ] in ]. Prior to this, the last Prime Minister to lose a confidence vote was ] in ]. | |||

| ], 1849]] | |||

| The actual site of Parliament shifted on a regular basis: From 1841 to 1844, it sat in ], where the present ] now stands; from 1844 until the ], the legislature was in ]; and, after a few years of alternating between Toronto and ], the legislature was finally moved to ] in 1856, ] having chosen that city as Canada's capital in 1857.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Rayburn |first1=Alan |last2=Harris |first2=Carolyn |title=Queen Victoria |url=https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/victoria |website=The Canadian Encyclopedia |access-date=21 November 2024}}</ref> | |||

| The modern-day Parliament of Canada came into existence in 1867, in which year the Parliament of the ] passed the ], uniting the provinces of ], ], and Canada—with the Province of Canada split into ] and ]—into a single federation called the ]. Though the form of the new federal legislature was again nearly identical to the Parliament of the United Kingdom, the decision to retain this model was made with heavy influence from the just-concluded ], which indicated to many ] the faults of the ] federal system, with its relatively powerful states and a less powerful federal government. The ''British North America Act'' limited the powers of the provinces, providing that all subjects not explicitly delegated to them by that document remain within the authority of the Canadian Parliament, while simultaneously giving the provinces unique powers in certain agreed-upon areas of jurisdiction. | |||

| ==Powers== | |||

| The powers of the Parliament of Canada are limited by the constitution, which divides legislative powers between the federal and provincial governments. In general, provincial Legislatures may only pass laws relating to topics explicitly reserved for them by the constitution, such as education, provincial officers, municipal government, charitable institutions, and "matters of a merely local or private nature." Under the constitution, any matter not under the exclusive authority of the provincial Legislatures is within the scope of Parliament's power. Thus, Parliament alone can pass laws relating to, amongst other things, the ], the ], the ], navigation and shipping, ], ], ]ing, ], ], ]s, ]s, ], and ]. In some cases, however, the powers of Parliament and the Legislatures seem to overlap. For instance, Parliament regulates ] and ] in general, but the solemnization of marriage is regulated only by the Legislatures. Other examples include the powers of both Parliament and the Legislatures to impose taxes, borrow money, punish crimes, and regulate ]. | |||

| ], 18 March 1918]] | |||

| The powers of the Canadian Parliament are also limited by the ]. Most of the provisions of the Charter may be overridden by an Act which includes a ]. Such a provision, however, has never been used by Parliament, though it has been employed by provincial Legislatures. Laws violating the Charter, as well as laws violating other parts of the constitution, are invalid, and may be ruled unconstitutional by the ]. | |||

| Full legislative autonomy was granted by the ], passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Though the statute allowed the Parliament of Canada to repeal or amend previously British laws as they applied to Canada, it did not permit amendment to Canada's constitution, including the British North America Acts. Hence, whenever a constitutional amendment was sought by the Canadian Parliament, the enactment of a British law was necessary, though Canada's consent was required. The Parliament of Canada was granted limited power to amend the constitution by a British Act of Parliament in 1949, but it was not permitted to affect the powers of provincial governments, the official positions of the English and French languages, rights of any class of persons with respect to schools, or the maximum five-year term of the legislature. | |||

| ==Privileges== | |||

| The Parliament of Canada possesses a number of privileges, known together as ]. Each House is the guardian of its own privileges, and may punish breaches thereof. Parliament itself determines the extent of parliamentary privilege, but the constitution bars it from conferring any privileges "exceeding those at the passing of such Act held, enjoyed, and exercised by the Commons … and by the Members thereof." | |||

| While her father, King ], had been the first Canadian monarch to grant royal assent in the legislature—doing so in 1939—Queen ] was the first sovereign to deliver the ]. This event, in 1957, was the first time television cameras were allowed into the chambers of parliament, as the ] broadcast the speech nation-wide.<ref>{{cite web| url=https://diefenbaker.usask.ca/exhibits/online-exhibits-content/the-crown-in-canada-en.php| title=The Crown in Canada (1957)| publisher=Diefenbaker Canada Centre| accessdate=21 August 2022}}</ref> | |||

| The foremost privilege held by both Houses is that of freedom of speech in debate: nothing said in either House may be questioned in any court or other institution outside Parliament. In particular, a member of either House cannot be sued for ] based on speeches made in the course of parliamentary proceedings. The only restraints on debate are placed by the Standing Orders (or rules) of the two Houses themselves. Another privilege of individual members is that of freedom from arrest in civil cases (but not for allegedly criminal actions). Members of both Houses are also privileged from jury service and attendance of courts as witnesses. | |||

| The Canadian House of Commons and Senate last requested the Parliament of the United Kingdom to enact a constitutional amendment in 1982, in the form of the '']'' which included the '']''.<ref></ref> This legislation terminated the power of the British Parliament's ability to legislate for Canada and the authority to amend the constitution was transferred to the Canadian House of Commons, the Senate, and the provincial legislative assemblies, acting jointly. Most amendments require the consent of the Senate, the House of Commons, and the ] of two-thirds of the provinces representing a majority of the population; the unanimous consent of provincial legislative assemblies is required for certain amendments, including those affecting the sovereign, the governor general, the ], the official status of the English and French languages, the ], and the amending formulas themselves. | |||

| Each House, furthermore, possesses privileges as a body, including the privilege of determining its own internal affairs and the privilege of disciplining its members for disobeying its rules. Furthermore, each House may punish ] (that is, disobedience of its authority, for example by giving false testimony before a parliamentary committee) and breaches of its own privileges. | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| {{portal|border=no|Canada|Politics}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *] |

*] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| == |

== Notes == | ||

| {{NoteFoot}} | |||

| == References == | |||

| * | |||

| === Citations === | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| == |

=== Sources === | ||

| {{Refbegin}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050308104218/http://www.parl.gc.ca/information/about/process/house/precis/titpg-e.htm |date=8 March 2005 }} | ||

| * | * | ||

| {{Refend}} | |||

| * | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Elections in Canada}} | |||

| *{{Official website}} | |||

| {{canleg}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{Canadian topics}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{featured article}} | |||

| {{Canadian Legislative Bodies}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Lists of Canadian parliaments}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Canada topics}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{National bicameral legislatures}} | |||

| {{Legislatures of the Americas}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{Coord|45.42521|N|75.70011|W|source:placeopedia|display=title}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 05:08, 7 January 2025

Bicameral federal legislature of Canada

The Parliament of Canada (French: Parlement du Canada) is the federal legislature of Canada, seated at Parliament Hill in Ottawa, and is composed of three parts: the King, the Senate, and the House of Commons. By constitutional convention, the House of Commons is dominant, with the Senate rarely opposing its will. The Senate reviews legislation from a less partisan standpoint and may initiate certain bills. The monarch or his representative, normally the governor general, provides royal assent to make bills into law. According to Section 16 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the official languages of the parliament are English and French.

The governor general, on behalf of the monarch, summons and appoints the 105 senators on the advice of the prime minister, while each of the 338 members of the House of Commons – called members of Parliament (MPs) – represents an electoral district, commonly referred to as a riding, and are elected by Canadian voters residing in the riding. The governor general also summons and calls together the House of Commons, and may prorogue or dissolve Parliament, in order to either end a parliamentary session or call a general election. The governor general also delivers the throne speech at the opening of each new Parliament (the monarch occasionally has done so, instead of the governor general, when visiting Canada).

The current Parliament, summoned by Governor General Mary Simon in November 2021, is the 44th Parliament since Confederation in 1867. On January 6, 2025, the Parliament was prorogued by Simon following prime minister Justin Trudeau's request to do so and will remain suspended until March 24.

Composition

The body consists of the King of Canada, represented by a viceroy, the governor general; an upper house, the Senate; and a lower house, the House of Commons. Each element has its own officers and organization. Each has a distinct role, but work in conjunction within the legislative process. This format was inherited from the United Kingdom and is a near-identical copy of the Parliament at Westminster, the greatest differences stemming from situations unique to Canada, such as the impermanent nature of the monarch's residency in the country and the lack of a peerage to form the upper chamber.

Only those who sit in the House of Commons are usually called members of Parliament (MPs); the term is not usually applied to senators (except in legislation, such as the Parliament of Canada Act), even though the Senate is a part of Parliament. Though legislatively less powerful, senators take higher positions in the national order of precedence. No individual may serve in more than one chamber at the same time.

Monarch

Main article: Monarchy of Canada § Parliament (King-in-Parliament)

The sovereign's place in the legislature, formally known as the King-in-Parliament, is defined by the Constitution Act, 1867, and various conventions. Neither he nor his viceroy, however, participates in the legislative process save for signifying the King's approval to a bill passed by both houses of Parliament, known as the granting of Royal Assent, which is necessary for a bill to be enacted as law. All federal bills thus begin with the phrase "Now, therefore, His Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate and House of Commons of Canada, enacts as follows ..." and, as such, the Crown is immune from acts of Parliament unless expressed otherwise in the act itself. The governor general will normally perform the task of granting Royal Assent, though the monarch may also do so, at the request of either the Cabinet or the viceroy, who may defer assent to the sovereign as per the constitution.