| Revision as of 13:48, 6 May 2007 editGreensburger (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users11,045 edits →Xisuthros← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 11:00, 29 October 2024 edit undoMonkbot (talk | contribs)Bots3,695,952 editsm Task 20: replace {lang-??} templates with {langx|??} ‹See Tfd› (Replaced 3);Tag: AWB | ||

| (313 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|King of Shuruppak (c. 2900 BC)}} | |||

| {{Mesopotamian myth (heroes)}} | |||

| {{Contains special characters|cuneiform}} | |||

| {{use dmy dates|date=April 2022}} | |||

| {{Infobox royalty | |||

| | name = Ziusudra<br />{{cuneiform|𒍣𒌓𒋤𒁺}} | |||

| | title = ]<br />] | |||

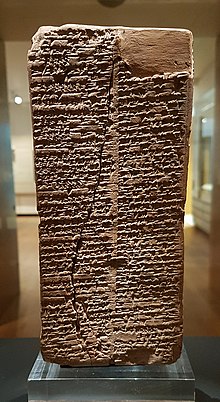

| | image = Sumerian King List, 1800 BC, Larsa, Iraq (detail).jpg | |||

| | image_size = | |||

| | caption = Sumerian King List, 1800 BC, Larsa, Iraq | |||

| | succession = ] king | |||

| | reign = {{circa|2900 BCE}} | |||

| | predecessor = ] | |||

| | successor = ''Deluge''<br />] of Kish | |||

| | spouse = | |||

| | dynasty = ] | |||

| | issue = | |||

| | father = ] ''(Akkadian tradition)'' | |||

| | mother = | |||

| | birth_date = | |||

| | birth_place = | |||

| | death_date = ''Immortal'' | |||

| | death_place = | |||

| | place of burial = | |||

| | religion = | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Ziusudra''' ({{langx|akk-x-oldbabyl|{{cuneiform|8|𒍣𒌓𒋤𒁺}}|translit=Ṣíusudrá}} , {{langx|akk-x-neoassyr|{{cuneiform|11|𒍣𒋤𒁕}}|translit=Ṣísudda}},{{sfn|Oracc}} {{langx|grc|Ξίσουθρος|translit=Xísouthros}}) of ] (c. 2900 BC) is listed in the WB-62 ] recension as the last king of ] prior to the ]. He is subsequently recorded as the hero of the ] and appears in the writings of ] as Xisuthros.{{citation needed|date=June 2019}} | |||

| ] '''Ziusudra''' ("life of long days", Hellenized ''Xisuthros''), ] '''Atrahasis''' ("extremely wise") and '''Utnapishtim''' ("he found life") are heroes of ]ern ]s. | |||

| Ziusudra is one of several mythic characters who are protagonists of ]ern flood myths, including ], ] and the biblical ]. Although each story displays its own distinctive features, many key story elements are common to two, three, or all four versions.{{Citation needed|date=June 2019}} | |||

| Although each version has distinctive story elements, there are numerous story elements that are common to two, or three, or four versions. The earliest version of the flood myth preserved fragmentarily is in the ], dating to ca. ], and is thus among the ] known. Strong parallels have been drawn with other stories, such as the Biblical story of ]. | |||

| ==Literary and archaeological evidence== | |||

| ==Ziusudra== | |||

| ===King Ziusudra of Shuruppak=== | |||

| {{Main|Sumerian king list}} | |||

| In the WB-62 ] recension, Ziusudra, or Zin-Suddu of ], is listed as son of the last king of Sumer before a great flood.{{sfn|Jacobsen|1939|pp=75 and 76; footnotes 32 and 34}} He is recorded as having reigned as both king and ''gudug'' priest for ten ''sars'' (periods of 3,600 years),{{sfn|Langdon|1923|pp=251–259}} although this figure is probably a ] for ten years.{{sfn|Best|1999|pp=118–119}} In this version, Ziusudra inherited rulership from his father ],{{sfn|Tablet XI, line 23}} who ruled for ten ''sars''.{{sfn|Langdon|1923|p=258, note 5}} | |||

| The lines following the mention of Ziusudra read: | |||

| The name Ziusudra means "found long life" or "life of long days". The tale of Ziusudra is known from a single fragmentary tablet, written in Sumerian, and published in 1914 by Arno Poebel.<ref>"The Sumerian Flood Story" in ''Atrahasis'', by Lambert and Millard, page 138</ref> The first part deals with the creation of man and the animals and the founding of the first cities - ], Badtibira, Larak, ], and ]. After a missing section in the tablet, we learn that the gods have decided to send a flood to destroy mankind. The god ] (lord of the underworld ocean of fresh water and Sumerian equivalent of Ea) warns Ziusudra of Shuruppak to build a large boat - the passage describing the directions for the boat is also lost. When the tablet resumes it is describing the flood. A terrible storm raged for seven days, "the huge boat had been tossed about on the great waters," then ] (the Sun) appears and Ziusudra opens a window, prostrates himself, and sacrifices an ox and a sheep. After another break the text resumes, the flood is apparently over, and Ziusudra is prostrating himself before ] (sky-god) and ] (chief of the gods), who give him "breath eternal" and take him to dwell in ]. The remainder of the poem is lost. | |||

| {{Quote|Then the flood swept over. After the flood had swept over, and the kingship had descended from heaven, the kingship was in Kish.{{sfn|ETCSL: Sumerian king list|n.d.}}}} | |||

| The Epic of Ziusudra adds this important story element at lines 258-261 not found in other versions, that after the river flood<ref>Lambert & Millard, page 97</ref> "king Ziusudra ... they caused to dwell in the land of the country of Dilmun, the place where the sun rises." Dilmun was an island in the Persian Gulf which suggests that Ziusudra's boat floated down the Euphrates river into the Persian Gulf and not up onto a mountain.<ref>Best, pages 30-31</ref> The Sumerian word KUR in line 140 of the ] was interpreted to mean mountain in Akkadian, but in Sumerian KUR did not mean mountain; KUR meant country, especially a foreign country. Dilmun was a foreign country. | |||

| The city of ] flourished in the ] soon after a river flood archaeologically attested by sedimentary strata at Shuruppak (modern ]), Uruk, Kish, and other sites, all of which have been ] to ca. 2900 BC.{{sfn|Crawford|1991|p=19}} ] pottery from the ] (ca. 30th century BC), which immediately preceded the Early Dynastic I period, was discovered directly below the Shuruppak flood stratum.{{sfn|Crawford|1991|p=19}}{{sfn|Schmidt|1931|pp=193–217}} ] wrote that "we know from the Weld Blundell prism that at the time of the Flood, Ziusudra, the Sumerian Noah, was King of the city of Shuruppak where he received warning of the impending disaster. His role as a saviour agrees with that assigned to his counterpart Utnapishtim in the Gilgamesh Epic. ... both epigraphical and archaeological discovery give good grounds for believing that Ziusudra was a prehistoric ruler of a well-known historic city the site of which has been identified."{{sfn|Mallowan|1964|pp=62–82}} | |||

| The name Ziusudra also appears in the WB-62 version of the ] as a king/chief of Shuruppak who reigned for 10 (shar) years.<ref>S. Langdon, "The Chaldean Kings Before the Flood," ''Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society'' (1923), pp 251-259.</ref> . Ziusudra was preceded in this king list by his father SU.KUR.LAM who was also king of Shuruppak and ruled 8 (shar) years.<ref>Langdon, p. 258, note 5.</ref> On the next line of the King List are the sentences "The flood swept thereover. After the flood swept thereover, ... the kingship was in Kish." The city of Kish flourished in the Early Dynastic II period soon after an archaeologically attested river flood in Shuruppak that has been radio-carbon dated about 2900 BC. <ref> Harriet Crawford, ''Sumer and the Sumerians'', Cambridge Univ. Press, 1991), p. 19.</ref> Polychrome pottery from below the flood deposit have be dated to the Jemdet Nasr period that immediately preceded the Early Dynastic I period.<ref> Erik Schmidt, ''Excavations at Fara'', 1931, University of Pennsylvania's ''Museum Journal'', 2 (1931), pp 193-217.</ref> | |||

| That Ziusudra was a king from Shuruppak is supported by the Gilgamesh XI tablet, which makes reference to Utnapishtim (the ] translation of the Sumerian name Ziusudra) with the epithet "man of Shuruppak" at line 23.{{sfn|Tablet XI, line 23|p=110}} | |||

| The importance of Ziusudra in the King List is that it links the flood mentioned in the Epics of Ziusudra, Atrahasis, Utnapishtim, etc to river flood sediments in Shuruppak, Uruk, and Kish that have been radio carbon dated as 2900 BC. So scholars conclude that the flood hero was king of Shuruppak at the end of the Jemdet Nasr period (3100-2900) which ended with the river flood of 2900 BC.<ref>M.E.L. Mallowan, "Noah's Flood Reconsidered", ''Iraq'', vol 26 (1964), pages 62-82.</ref> | |||

| ===Sumerian flood myth=== | |||

| Ziusudra being king of Shuruppak is supported in the Gilgamesh XI tablet by the reference to Utnapishtim as "man of Shuruppak" at line 23. | |||

| {{main|Eridu Genesis}} | |||

| The tale of Ziusudra is known from a single fragmentary tablet written in Sumerian, datable by its script to the 17th century BC (]), and published in 1914 by Arno Poebel.{{sfn|Lambert|Millard|1999|p=138}} The first part deals with the creation of man and the animals and the founding of the first cities ], ], ], ], and ]. After a missing section in the tablet, we learn that the gods have decided to send a flood to destroy mankind. The god ] (lord of the underworld sea of fresh water and Sumerian equivalent of Babylonian god Ea) warns Ziusudra, the ruler of Shuruppak, to build a large boat; the passage describing the directions for the boat is also lost. When the tablet resumes, it is describing the flood. A terrible storm raged for seven days, "the huge boat had been tossed about on the great waters," then ] (Sun) appears and Ziusudra opens a window, prostrates himself, and sacrifices an ox and a sheep. After another break, the text resumes, the flood is apparently over, and Ziusudra is prostrating himself before ] (Sky) and ] (Lordbreath), who give him "breath eternal" and take him to dwell in ]. The remainder of the poem is lost.{{sfn|Kramer|1961}}{{failed verification|date=May 2018}} | |||

| The Epic of Ziusudra adds an element at lines 258–261 not found in other versions, that after the flood{{sfn|Lambert|Millard|1999|p=97}} "king Ziusudra ... they caused to dwell in the ''KUR'' ], the place where the sun rises". The Sumerian word "KUR" is an ambiguous word. Samuel Noah Kramer states that "its primary meanings is 'mountain' is attested by the fact that the sign used for it is actually a pictograph representing a mountain. From the meaning 'mountain' developed that of 'foreign land', since the mountainous countries bordering Sumer were a constant menace to its people. Kur also came to mean 'land' in general".{{sfn|Kramer|1961}} The last sentence can be translated as "In the mountain of crossing, the mountain of Dilmun, the place where the sun rises".{{sfn|Kramer|1961}} | |||

| A Sumerian document known as "The Instructions of Shuruppak" dated by Kramer about 2500 BC, refers in a later version to Ziusudra. Kramer concluded that "Ziusudra had become a venerable figure in literary tradition by the middle of the third millennium B.C."<ref> Samuel Noah Kramer, "Reflections on the Mesopotamian Flood," ''Expedition'', 9, 4, (summer 1967), pp 12-18. </ref> | |||

| A Sumerian document known as the '']'' dated by Kramer to about 2600 BC, refers in a later version to Ziusudra. Kramer stated "Ziusudra had become a venerable figure in literary tradition by the middle of the third millennium B.C."{{sfn|Kramer|1967|p=16, col.2}} | |||

| Scholars have noted many similarities between the stories of Ziusudra, Atrahasis, Utnapishtim and ]. | |||

| ===Xisuthros=== | ===Xisuthros=== | ||

| ''Xisuthros'' ( |

''Xisuthros'' (Ξίσουθρος) is a ] of the Sumerian Ziusudra, known from the writings of ], a priest of ] in Babylon, on whom ] relied heavily for information on Mesopotamia. Among the interesting features of this version of the flood myth, are the identification, through '']'', of the Sumerian god ] with the Greek god ], the father of ]; and the assertion that the ] constructed by Xisuthros survived, at least until Berossus' day, in the "Corcyrean Mountains" of ]. Xisuthros was listed as a king, the son of one Ardates, and to have reigned 18 ''saroi''. One saros (''shar'' in Akkadian) stands for 3600 and hence 18 ''saroi'' was translated as 64,800 years. | ||

| A saroi or saros is an astrologolical term defined as 222 lunar months of 29.5 days or 18.5 lunar years equal to 17.93 solar years. | |||

| == |

===Other sources=== | ||

| Ziusudra is also mentioned in other ancient literature, including ''The Death of Gilgamesh''{{sfn|ETCSL: t.1.8.1.3}} and ''The Poem of Early Rulers'',{{sfn|ETCSL: t.5.2.5}} and a late version of '']''.{{sfn|ETCSL: t.5.6.1}} | |||

| {{main|Atrahasis}} | |||

| The ] Atrahasis Epic tells how the god Enki warns the hero Atrahasis ("Extremely Wise") to build a boat to escape a flood. The Epic of Ziusudra does not make it clear whether the flood was a river flood or something else. But the Epic of ] tablet III iv, lines 6-9 clearly identifies the flood as a local river flood: "Like dragonflies they have filled the river. Like a raft they have moved in to the edge . Like a raft they have moved in to the riverbank." | |||

| The Epic of ] provides additional information on the flood and flood hero that is omitted in Gilgamesh XI and other versions of the Ancient Near East flood myth. Similarly, the Gilgamesh XI flood text provides additional information that is missing in damaged portions of the Atrahasis tablets. | |||

| At lines 6 and 7 of tablet RS 22.421 we are told "I am Atrahasis. I lived in the temple of Ea , my Lord." Prior to the Early Dynastic period, kings were subordinate to priests and often lived in the same temple complex where the priests lived. | |||

| Tablet III,ii lines 55-56 of Atrahasis state that "He severed the mooring line and set the boat adrift." This is consistent with a river flood. If Atrahasis severed the mooring lines, the runaway boat would go down the river into the Persian Gulf. | |||

| ==Utnapishtim== | |||

| {{main|Gilgamesh flood myth}} | |||

| In the eleventh tablet of the Babylonian '']'', '''Utnapishtim''' "the faraway" is the wise king of the ]ian ] of ] who, along with his unnamed wife, survived a ] sent by ] to drown every living thing on Earth. Utnapishtim was secretly warned by the water god ] of Enlil's plan and constructed a great boat or ark to save himself, his family and representatives of each species of animal. When the flood waters subsided, the boat was grounded on the mountain of ]. When Utnapishtim's ark had been becalmed for seven days, he released a ], who found no resting place and returned. A ] was then released who found no perch and also returned, but the ] which was released third did not return. Utnapishtim then made a sacrifice and poured out a libation to Ea on the top of mount ]. Utnapishtim and his wife were granted ] after the flood. Afterwards, he is taken by the gods to live forever at "the mouth of the rivers" and given the ] "faraway". | |||

| The Babylonian myth of Utnapishtim (meaning "He found life", presumably in reference to the gift of immortality given him by the gods) is matched by the earlier Epic of Atrahasis, and by the Sumerian version, the Epic of Ziusudra. | |||

| ==Noah== | |||

| {{main|Noah}} | |||

| The similarities between the story of Noah's Ark, the Sumerian story of Ziusudra, and the Babylonian stories of Atrahasis and Utnapishtim are clearly shown by corresponding lines in various versions: | |||

| <blockquote>"the storm had swept...for seven days and seven nights" — Ziusudra 203 | |||

| <br>"For seven days and seven nights came the storm" — Atrahasis III,iv, 24 | |||

| <br>"Six days and seven nights the wind and storm" — Gilgamesh XI, 127 | |||

| <br>"rain fell upon the earth forty days and forty nights" — Genesis 7:12</blockquote> | |||

| <blockquote>"He offered a sacrifice" — Atrahasis III,v, 31 | |||

| <br>"And offered a sacrifice" — Gilgamesh XI, 155 | |||

| <br>"offered burnt offerings on the altar" — Genesis 8:20 | |||

| <br>"built an altar and sacrificed to the gods" — Berossus.</blockquote> | |||

| <blockquote>"The gods smelled the savor" — Atrahasis III,v,34 | |||

| <br>"The gods smelled the sweet savor" — Gilgamesh XI, 160 | |||

| <br>"And the Lord smelled the sweet savor..." — Genesis 8:21</blockquote> | |||

| The ] flood story of ] 6-9 dates to at least the ]. According to the ], it is a composite of two literary sources ] and ] that were combined by a post-exilic editor, 539-400 BC. | |||

| Hans Schmid believes both the J material and the P material were products of the ] period (6th century BC) and were directly derived from Babylonian sources (see also ]).<ref>Hans Heinrich Schmid, ''The So-Called Yahwist'' (1976) discussed in Antony F. Campbell and Mark A. O'Brien, ''Sources of the Pentateuch'' (1993) pp 2-11, note 24.</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| *] | * ] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| == |

==Notes== | ||

| <!-- See ] for instructions. --> | <!-- See ] for instructions. --> | ||

| {{Reflist|20em}} | |||

| ==Sources== | |||

| * W. G. Lambert and ], ''Atrahasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood'', Eisenbrauns, 1999, ISBN 1-57506-039-6. | |||

| {{refbegin|35em}} | |||

| * R. M. Best, ''Noah's Ark and the Ziusudra Epic'', Eisenbrauns, 1999, ISBN 0-9667840-1-4. | |||

| *{{citation| title = Noah's Ark and the Ziusudra Epic | |||

| | last = Best | first = R. M. | year = 1999 | |||

| | publisher = Eisenbrauns | |||

| | isbn = 0-9667840-1-4 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{citation| title = Sumer and the Sumerians | |||

| | last = Crawford | first = Harriet | author-link=Harriet Crawford |year = 1991 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | isbn = 978-052138175-8 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{citation| title = Myths from Mesopotamia | |||

| | last = Dalley | first = Stephanie | year = 2008 | |||

| | page = 110 | |||

| | ref = {{harvid|Tablet XI, line 23}} | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{citation| title = ETCSLtranslation: t.1.8.1.3 The death of Gilgameš | |||

| | website = The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature | |||

| | publisher = Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford | |||

| | year = 2006 | |||

| | url = http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.8.1.3 | |||

| | ref = {{harvid|ETCSL: t.1.8.1.3}} | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{citation| title = ETCSLtranslation: t.5.2.5 The poem of early rulers | |||

| | website = The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature | |||

| | publisher = Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford | |||

| | year = 2006 | |||

| | url = http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.5.2.5 | |||

| | ref = {{harvid|ETCSL: t.5.2.5}} | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{citation| title = ETCSLtranslation: t.5.6.1 The instructions of Šuruppag | |||

| | website = The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature | |||

| | publisher = Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford | |||

| | year = 2006 | |||

| | url = http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.5.6.1 | |||

| | ref = {{harvid|ETCSL: t.5.6.1}} | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{citation| title = The Sumerian King List | |||

| | last = Jacobsen | first = Thorkild | year = 1939 | |||

| | author-link = Thorkild Jacobsen | |||

| | pages = 75 and 76; footnotes 32 and 34 | |||

| | publisher = University of Chicago Press | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{citation| title = Sumerian Mythology: Miscellaneous Myths | |||

| | last = Kramer | first = Samuel Noah | year = 1961 | |||

| | website = Internet Sacred Text Archive | |||

| | publisher = University of Pennsylvania Press | |||

| | url = http://www.sacred-texts.com/ane/sum/sum09.htm | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{citation | |||

| | title = Reflections on the Mesopotamian Flood | |||

| | last = Kramer | |||

| | first = Samuel Noah | |||

| | year = 1967 | |||

| | magazine = Expedition Magazine | |||

| | volume = 9 | |||

| | issue = 4 | |||

| | publisher = Penn Museum | |||

| | at = p.16, col.2 | |||

| | url = https://www.penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/PDFs/9-4/Reflections.pdf | |||

| | access-date = 28 May 2018 | |||

| | archive-date = 19 June 2021 | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210619071900/https://www.penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/PDFs/9-4/Reflections.pdf | |||

| | url-status = dead | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{citation| title = Atrahasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood | |||

| | last1 = Lambert | first1 = W. G. | |||

| | last2 = Millard | first2 = A. R. | |||

| | author1-link = Wilfred G. Lambert | |||

| | author2-link = Alan Millard | |||

| | year = 1999 | |||

| | publisher = Eisenbrauns | |||

| | isbn = 1-57506-039-6 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{citation| title = The Chaldean Kings Before the Flood | |||

| | last = Langdon | first = S. | year = 1923 | |||

| | journal = Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{citation| title = Noah's Flood Reconsidered | |||

| | last = Mallowan | first = M.E.L. | year = 1964 | |||

| | journal = Iraq | |||

| | volume = 26 | issue = 2 | pages = 62–82 | |||

| | doi = 10.2307/4199766 | jstor = 4199766 | |||

| | s2cid = 128633634 }} | |||

| *{{citation| title = Excavations at Fara | |||

| | last = Schmidt | first = Erik | year = 1931 | |||

| | journal = The Museum Journal | via = ] | |||

| | volume = 22 | issue = 2 | pages = 193–217 | |||

| | url = https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.530864 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{citation| title = The Sumerian king list: translation | |||

| | website = The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature | |||

| | publisher = Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford | |||

| | url = http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section2/tr211.htm | url-status = live | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080508061030/http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section2/tr211.htm | |||

| | date = n.d. | archive-date = 8 May 2008 | |||

| | ref = {{harvid|ETCSL: Sumerian king list|n.d.}} | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{citation| title = Ziusudra | |||

| | website = Oracc: The Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus | |||

| | url = http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/epsd2/cbd/sux/o0048582.html | |||

| | ref = {{harvid|Oracc}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| * | |||

| * All texts: (, , , , , , ), commentary, and a | |||

| * () | |||

| {{s-start}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{s-bef| rows = 2 | before = ] of ]}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{s-ttl| title = ] | |||

| | years = c. legendary or 2900 BC | |||

| }} | |||

| {{s-aft|after=] of ]}} | |||

| {{s-ttl| title = ] of ] | |||

| | years = c. legendary or 2900 BC | |||

| }} | |||

| {{s-non|reason=City flooded according to legend}} | |||

| {{s-end}} | |||

| {{Sumerian King List}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Ancient Near East}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Sumerian mythology}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Ziusudra}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Notable Rulers of Sumer}} | |||

Latest revision as of 11:00, 29 October 2024

King of Shuruppak (c. 2900 BC)

| Ziusudra 𒍣𒌓𒋤𒁺 | |

|---|---|

| King of Shuruppak King of Sumer | |

Sumerian King List, 1800 BC, Larsa, Iraq Sumerian King List, 1800 BC, Larsa, Iraq | |

| Antediluvian king | |

| Reign | c. 2900 BCE |

| Predecessor | Ubara-tutu |

| Successor | Deluge Jushur of Kish |

| Died | Immortal |

| Dynasty | Antediluvian |

| Father | Ubara-tutu (Akkadian tradition) |

Ziusudra (Old Babylonian Akkadian: 𒍣𒌓𒋤𒁺, romanized: Ṣíusudrá , Neo-Assyrian Akkadian: 𒍣𒋤𒁕, romanized: Ṣísudda, Ancient Greek: Ξίσουθρος, romanized: Xísouthros) of Shuruppak (c. 2900 BC) is listed in the WB-62 Sumerian King List recension as the last king of Sumer prior to the Great Flood. He is subsequently recorded as the hero of the Eridu Genesis and appears in the writings of Berossus as Xisuthros.

Ziusudra is one of several mythic characters who are protagonists of Near Eastern flood myths, including Atrahasis, Utnapishtim and the biblical Noah. Although each story displays its own distinctive features, many key story elements are common to two, three, or all four versions.

Literary and archaeological evidence

King Ziusudra of Shuruppak

Main article: Sumerian king listIn the WB-62 Sumerian king list recension, Ziusudra, or Zin-Suddu of Shuruppak, is listed as son of the last king of Sumer before a great flood. He is recorded as having reigned as both king and gudug priest for ten sars (periods of 3,600 years), although this figure is probably a copyist error for ten years. In this version, Ziusudra inherited rulership from his father Ubara-Tutu, who ruled for ten sars.

The lines following the mention of Ziusudra read:

Then the flood swept over. After the flood had swept over, and the kingship had descended from heaven, the kingship was in Kish.

The city of Kish flourished in the Early Dynastic period soon after a river flood archaeologically attested by sedimentary strata at Shuruppak (modern Tell Fara), Uruk, Kish, and other sites, all of which have been radiocarbon dated to ca. 2900 BC. Polychrome pottery from the Jemdet Nasr period (ca. 30th century BC), which immediately preceded the Early Dynastic I period, was discovered directly below the Shuruppak flood stratum. Max Mallowan wrote that "we know from the Weld Blundell prism that at the time of the Flood, Ziusudra, the Sumerian Noah, was King of the city of Shuruppak where he received warning of the impending disaster. His role as a saviour agrees with that assigned to his counterpart Utnapishtim in the Gilgamesh Epic. ... both epigraphical and archaeological discovery give good grounds for believing that Ziusudra was a prehistoric ruler of a well-known historic city the site of which has been identified."

That Ziusudra was a king from Shuruppak is supported by the Gilgamesh XI tablet, which makes reference to Utnapishtim (the Akkadian translation of the Sumerian name Ziusudra) with the epithet "man of Shuruppak" at line 23.

Sumerian flood myth

Main article: Eridu GenesisThe tale of Ziusudra is known from a single fragmentary tablet written in Sumerian, datable by its script to the 17th century BC (Old Babylonian Empire), and published in 1914 by Arno Poebel. The first part deals with the creation of man and the animals and the founding of the first cities Eridu, Bad-tibira, Larak, Sippar, and Shuruppak. After a missing section in the tablet, we learn that the gods have decided to send a flood to destroy mankind. The god Enki (lord of the underworld sea of fresh water and Sumerian equivalent of Babylonian god Ea) warns Ziusudra, the ruler of Shuruppak, to build a large boat; the passage describing the directions for the boat is also lost. When the tablet resumes, it is describing the flood. A terrible storm raged for seven days, "the huge boat had been tossed about on the great waters," then Utu (Sun) appears and Ziusudra opens a window, prostrates himself, and sacrifices an ox and a sheep. After another break, the text resumes, the flood is apparently over, and Ziusudra is prostrating himself before An (Sky) and Enlil (Lordbreath), who give him "breath eternal" and take him to dwell in Dilmun. The remainder of the poem is lost.

The Epic of Ziusudra adds an element at lines 258–261 not found in other versions, that after the flood "king Ziusudra ... they caused to dwell in the KUR Dilmun, the place where the sun rises". The Sumerian word "KUR" is an ambiguous word. Samuel Noah Kramer states that "its primary meanings is 'mountain' is attested by the fact that the sign used for it is actually a pictograph representing a mountain. From the meaning 'mountain' developed that of 'foreign land', since the mountainous countries bordering Sumer were a constant menace to its people. Kur also came to mean 'land' in general". The last sentence can be translated as "In the mountain of crossing, the mountain of Dilmun, the place where the sun rises".

A Sumerian document known as the Instructions of Shuruppak dated by Kramer to about 2600 BC, refers in a later version to Ziusudra. Kramer stated "Ziusudra had become a venerable figure in literary tradition by the middle of the third millennium B.C."

Xisuthros

Xisuthros (Ξίσουθρος) is a Hellenization of the Sumerian Ziusudra, known from the writings of Berossus, a priest of Bel in Babylon, on whom Alexander Polyhistor relied heavily for information on Mesopotamia. Among the interesting features of this version of the flood myth, are the identification, through interpretatio graeca, of the Sumerian god Enki with the Greek god Cronus, the father of Zeus; and the assertion that the reed boat constructed by Xisuthros survived, at least until Berossus' day, in the "Corcyrean Mountains" of Armenia. Xisuthros was listed as a king, the son of one Ardates, and to have reigned 18 saroi. One saros (shar in Akkadian) stands for 3600 and hence 18 saroi was translated as 64,800 years. A saroi or saros is an astrologolical term defined as 222 lunar months of 29.5 days or 18.5 lunar years equal to 17.93 solar years.

Other sources

Ziusudra is also mentioned in other ancient literature, including The Death of Gilgamesh and The Poem of Early Rulers, and a late version of The Instructions of Shuruppak.

See also

Notes

- Oracc.

- Jacobsen 1939, pp. 75 and 76, footnotes 32 and 34.

- Langdon 1923, pp. 251–259.

- Best 1999, pp. 118–119.

- Tablet XI, line 23.

- Langdon 1923, p. 258, note 5.

- ETCSL: Sumerian king list n.d.

- ^ Crawford 1991, p. 19.

- Schmidt 1931, pp. 193–217.

- Mallowan 1964, pp. 62–82.

- Tablet XI, line 23, p. 110.

- Lambert & Millard 1999, p. 138.

- ^ Kramer 1961.

- Lambert & Millard 1999, p. 97.

- Kramer 1967, p. 16, col.2.

- ETCSL: t.1.8.1.3.

- ETCSL: t.5.2.5.

- ETCSL: t.5.6.1.

Sources

- Best, R. M. (1999), Noah's Ark and the Ziusudra Epic, Eisenbrauns, ISBN 0-9667840-1-4

- Crawford, Harriet (1991), Sumer and the Sumerians, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-052138175-8

- Dalley, Stephanie (2008), Myths from Mesopotamia, p. 110

- "ETCSLtranslation: t.1.8.1.3 The death of Gilgameš", The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford, 2006

- "ETCSLtranslation: t.5.2.5 The poem of early rulers", The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford, 2006

- "ETCSLtranslation: t.5.6.1 The instructions of Šuruppag", The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford, 2006

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1939), The Sumerian King List, University of Chicago Press, pp. 75 and 76, footnotes 32 and 34

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1961), "Sumerian Mythology: Miscellaneous Myths", Internet Sacred Text Archive, University of Pennsylvania Press

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1967), "Reflections on the Mesopotamian Flood" (PDF), Expedition Magazine, vol. 9, no. 4, Penn Museum, p.16, col.2, archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2021, retrieved 28 May 2018

- Lambert, W. G.; Millard, A. R. (1999), Atrahasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood, Eisenbrauns, ISBN 1-57506-039-6

- Langdon, S. (1923), "The Chaldean Kings Before the Flood", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society

- Mallowan, M.E.L. (1964), "Noah's Flood Reconsidered", Iraq, 26 (2): 62–82, doi:10.2307/4199766, JSTOR 4199766, S2CID 128633634

- Schmidt, Erik (1931), "Excavations at Fara", The Museum Journal, 22 (2): 193–217 – via Internet Archive

- "The Sumerian king list: translation", The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford, n.d., archived from the original on 8 May 2008

- "Ziusudra", Oracc: The Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus

External links

- A comparison of equivalent lines in six ancient versions of the flood story

- Ancient Near East flood myths All texts: (Eridu Genesis, Atrahasis, Gilgamesh, Bible, Berossus, Greece, Quran), commentary, and a table with parallels

- ETCSL – Text and translation of the Sumerian flood story (alternate site)

| Preceded byUbara-Tutu of Shuruppak | King of Sumer c. legendary or 2900 BC |

Succeeded byJushur of Kish |

| Ensi of Shuruppak c. legendary or 2900 BC |

City flooded according to legend |

| Rulers in the Sumerian King List | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

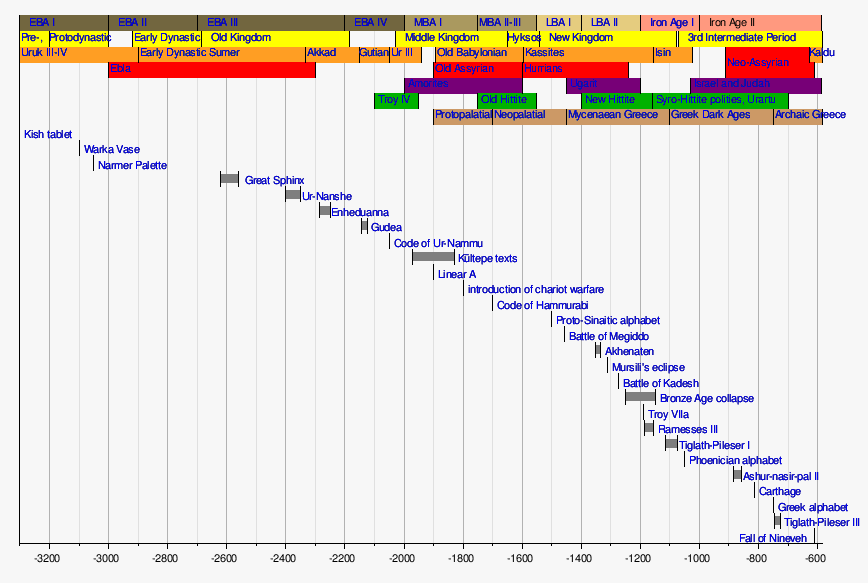

| Timeline of the ancient Near East | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sumerian mythology | ||

|---|---|---|

| Primordial beings |  | |

| Primary deities | ||

| Other major deities | ||

| Minor deities | ||

| Demons, spirits, and monsters | ||

| Mortal heroes | ||