| Revision as of 00:32, 30 May 2005 editHillman (talk | contribs)11,881 edits →Online notes and courses: Added a few more links, converted all links into Web reference template form.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:48, 28 December 2024 edit undo2603:6000:d400:c523:b025:6bb5:12f9:59f (talk) →Light deflection and gravitational time delay | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Theory of gravitation as curved spacetime}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{For|the graduate textbook by Robert Wald|General Relativity (book){{!}}''General Relativity'' (book)}} | |||

| {{For introduction}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2022}} | |||

| ] GW150914 as seen by a nearby observer, during 0.33 s of its final ], ], and ]. The star field behind the black holes is being heavily distorted and appears to rotate and move, due to extreme ]ing, as ] itself is distorted and dragged around by the rotating ]s.<ref name="SXSproject">{{cite web |url=http://www.black-holes.org/gw150914 |title=GW150914: LIGO Detects Gravitational Waves |website=Black-holes.org |access-date=18 April 2016}}</ref>]] | |||

| {{General relativity sidebar}} | |||

| '''General relativity''', also known as the '''general theory of relativity''', and as '''Einstein's theory of gravity''', is the ] ] of ] published by ] in 1915 and is the current description of gravitation in ]. General ] generalizes ] and refines ], providing a unified description of gravity as a geometric property of ] and ], or ] ]. In particular, the ''] of spacetime'' is directly related to the ] and ] of whatever present ] and ]. The relation is specified by the ], a system of second-order ]s. | |||

| '''General relativity (GR)''' or '''general relativity theory (GRT)''' is a fundamental ] ] of ] which corrects and extends ], especially at the macroscopic level of stars or planets. | |||

| ], which describes classical gravity, can be seen as a prediction of general relativity for the almost flat spacetime geometry around stationary mass distributions. Some predictions of general relativity, however, are beyond ] in ]. These predictions concern the passage of time, the ] of space, the motion of bodies in ], and the propagation of light, and include ], ]ing, the ] of light, the ] and ]/]. So far, all ] have been shown to be in agreement with the theory. The time-dependent solutions of general relativity enable us to talk about the history of the universe and have provided the modern framework for ], thus leading to the discovery of the ] and ] radiation. Despite the introduction of a number of ], general relativity continues to be the simplest theory consistent with ]. | |||

| General relativity may be regarded as an extension of ], this latter theory correcting ] at high velocities. General relativity has a unique role amongst physical theories in the sense that it interprets the ] as a geometric phenomenon. More specifically, it assumes that any object possessing mass curves the 'space' in which it exists, this curvature being equated to gravity. To conceptualize this equivalence, it is helpful to think, as several author-physicists have suggested, in terms of gravity not causing or being caused by spacetime curvature, but rather that '''gravity is spacetime curvature'''. It deals with the motion of bodies in such 'curved spaces' and has survived every experimental test performed on it since its formulation by ] in 1915. | |||

| Reconciliation of general relativity with the laws of ] remains a problem, however, as there is a lack of a self-consistent theory of ]. It is not yet known how gravity can be ] with the three non-gravitational forces: ], ] and ]. | |||

| General relativity forms the basis for modern studies in fields such as ], ] and ]. It describes with great ] many phenomena where classical physics fails, such as the perihelion motion of planets (classical physics cannot fully account for the perihelion shift of Mercury, for example) and the ] by the Sun (again, classical physics can only account for half the experimentally observed bending). It also predicts phenomena such as the ], ] and the ]. In fact, even Einstein himself initially believed that the universe cannot be expanding, but experimental observations of distant galaxies by ] finally forced ] to concede. | |||

| Einstein's theory has ] implications, including the prediction of ]—regions of space in which space and time are distorted in such a way that nothing, not even ], can escape from them. Black holes are the end-state for ]s. ]s and ] are believed to be ]s and ]s. It also predicts ], where the bending of light results in multiple images of the same distant astronomical phenomenon. Other predictions include the existence of ]s, which have been ] by the physics collaboration ] and other observatories. In addition, general relativity has provided the base of ] models of an ]. | |||

| Unlike the other revolutionary physical theory, ], general relativity was essentially formulated by one man - Albert Einstein. However, Einstein required the help of one of his friends, ], to help him with the mathematics of curved manifolds. | |||

| <!-- Before any further attempt of deleting the following claim, please, note its sources in the History section, and the conclusive consensus on the TP. --> | |||

| == Physical Description of the Theory == | |||

| Widely acknowledged as a theory of extraordinary ], general relativity has often been described as the most beautiful of all existing physical theories.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| {{TOC limit|limit=3}} | |||

| In relativity theory, physical phenomena are described by observers making measurements in ]. In general relativity, these reference frames are arbitrarily moving relative to each other (unlike in ], where the reference frames are assumed to be ]). | |||

| == History == | |||

| Consider two such reference frames, for example, one situated on Earth (the 'Earth-frame'), and another in orbit around the Earth (the 'orbit-frame'). An observer (O) in the orbit-frame will feel weightless as they 'fall' towards the Earth. | |||

| {{Main|History of general relativity|Classical theories of gravitation}} | |||

| ]'s 1905 theory of the dynamics of the electron was a relativistic theory which he applied to all forces, including gravity. While others thought that gravity was instantaneous or of electromagnetic origin, he suggested that relativity was "something due to our methods of measurement". In his theory, he showed that ] propagate at the speed of light.<ref>{{Harvnb|Poincaré|1905}}</ref> Soon afterwards, Einstein started thinking about how to incorporate ] into his relativistic framework. In 1907, beginning with a simple ] involving an observer in free fall (FFO), he embarked on what would be an eight-year search for a relativistic theory of gravity. After numerous detours and false starts, his work culminated in the presentation to the ] in November 1915 of what are now known as the Einstein field equations, which form the core of Einstein's general theory of relativity.<ref>{{cite web|last1=O'Connor|first1=J.J.|last2=Robertson|first2=E.F.|date=May 1996|url= http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/HistTopics/General_relativity.html|title=General relativity]}} {{Citation|url= http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/Indexes/Math_Physics.html|title=History Topics: Mathematical Physics Index|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20150204231934/http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/Indexes/Math_Physics.html|archive-date=4 February 2015|publisher=School of Mathematics and Statistics, ]|location=Scotland|access-date=4 February 2015}}</ref> These equations specify how the geometry of space and time is influenced by whatever matter and radiation are present.<ref>{{Harvnb|Pais|1982|loc=ch. 9 to 15}}, {{Harvnb|Janssen|2005}}; an up-to-date collection of current research, including reprints of many of the original articles, is {{Harvnb|Renn|2007}}; an accessible overview can be found in {{Harvnb|Renn|2005|pp=110ff}}. Einstein's original papers are found in , volumes 4 and 6. An early key article is {{Harvnb|Einstein|1907}}, cf. {{Harvnb|Pais|1982|loc=ch. 9}}. The publication featuring the field equations is {{Harvnb|Einstein|1915}}, cf. {{Harvnb|Pais|1982|loc=ch. 11–15}}</ref> A version of ], called ], enabled Einstein to develop general relativity by providing the key mathematical framework on which he fit his physical ideas of gravity.<ref>Moshe Carmeli (2008).Relativity: Modern Large-Scale Structures of the Cosmos. pp.92, 93.World Scientific Publishing</ref> This idea was pointed out by mathematician ] and published by Grossmann and Einstein in 1913.<ref>Grossmann for the mathematical part and Einstein for the physical part (1913). Entwurf einer verallgemeinerten Relativitätstheorie und einer Theorie der Gravitation (Outline of a Generalized Theory of Relativity and of a Theory of Gravitation), Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik, 62, 225–261. </ref> | |||

| The Einstein field equations are ] and considered difficult to solve. Einstein used approximation methods in working out initial predictions of the theory. But in 1916, the astrophysicist ] found the first non-trivial exact solution to the Einstein field equations, the ]. This solution laid the groundwork for the description of the final stages of gravitational collapse, and the objects known today as black holes. In the same year, the first steps towards generalizing Schwarzschild's solution to ] objects were taken, eventually resulting in the ], which is now associated with ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Schwarzschild|1916a}}, {{Harvnb|Schwarzschild|1916b}} and {{Harvnb|Reissner|1916}} (later complemented in {{Harvnb|Nordström|1918}})</ref> In 1917, Einstein applied his theory to the ] as a whole, initiating the field of relativistic cosmology. In line with contemporary thinking, he assumed a static universe, adding a new parameter to his original field equations—the ]—to match that observational presumption.<ref>{{Harvnb|Einstein|1917}}, cf. {{Harvnb|Pais|1982|loc=ch. 15e}}</ref> By 1929, however, the work of ] and others had shown that the universe is expanding. This is readily described by the expanding cosmological solutions found by ] in 1922, which do not require a cosmological constant. ] used these solutions to formulate the earliest version of the ] models, in which the universe has evolved from an extremely hot and dense earlier state.<ref>Hubble's original article is {{Harvnb|Hubble|1929}}; an accessible overview is given in {{Harvnb|Singh|2004|loc=ch. 2–4}}</ref> Einstein later declared the cosmological constant the biggest blunder of his life.<ref>As reported in {{Harvnb|Gamow|1970}}. Einstein's condemnation would prove to be premature, cf. the section ], below</ref> | |||

| In Newtonian gravitation, O's motion is explained by the ] formulation of gravity, where it is assumed that a force between the Earth and O causes O to move around the Earth. | |||

| During that period, general relativity remained something of a curiosity among physical theories. It was clearly superior to ], being consistent with special relativity and accounting for several effects unexplained by the Newtonian theory. Einstein showed in 1915 how his theory explained the ] of the planet ] without any arbitrary parameters ("]"),<ref>{{Harvnb|Pais|1982|pp=253–254}}</ref> and in 1919 an expedition led by ] confirmed general relativity's prediction for the deflection of starlight by the Sun during the total ],<ref>{{Harvnb|Kennefick|2005}}, {{Harvnb|Kennefick|2007}}</ref> instantly making Einstein famous.<ref>{{Harvnb|Pais|1982|loc=ch. 16}}</ref> Yet the theory remained outside the mainstream of ] and astrophysics until developments between approximately 1960 and 1975, now known as the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Thorne|2003|p=}}</ref> Physicists began to understand the concept of a black hole, and to identify ]s as one of these objects' astrophysical manifestations.<ref>{{Harvnb|Israel|1987|loc=ch. 7.8–7.10}}, {{Harvnb|Thorne|1994|loc=ch. 3–9}}</ref> Ever more precise solar system tests confirmed the theory's predictive power,<ref>Sections ], ] and ], and references therein</ref> and relativistic cosmology also became amenable to direct observational tests.<ref>Section ] and references therein; the historical development is in {{Harvnb|Overbye|1999}}</ref> | |||

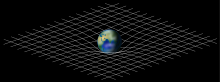

| General relativity views the situation in a different manner, namely, by demonstrating that the Earth modifies ('warps') the geometry in its vicinity and O will naturally follow the curves (]) in this geometry unless O applies accelerative force (e.g. rockets). More precisely, the presence of matter determines the geometry of ], the physical arena in which all ] take place. This is a profound innovation in physics, all other physical theories assuming the structure of the spacetime in advance. It is important to note that a given matter distribution will fix the spacetime once and for all. There are a few caveats here: (1) the spacetime within which the matter is distributed cannot be properly defined without the matter, so most solutions require special assumptions, such as symmetries, to allow the relativist to concoct a candidate spacetime, then see where the matter must lie, then require its properties be "reasonable" and so on. (2) Initial and boundary conditions can also be a problem, so that ] may violate the idea of the spacetime being fixed once and for all. | |||

| General relativity has acquired a reputation as a theory of extraordinary beauty.<ref name=":0">{{Harvnb|Landau|Lifshitz|1975|loc=p. 228}} "...the ''general theory of relativity''...was established by Einstein, and represents probably the most beautiful of all existing physical theories."</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Wald|1984|loc=p. 3}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Rovelli|2015|loc=pp. 1–6}} "General relativity is not just an extraordinarily beautiful physical theory providing the best description of the gravitational interaction we have so far. It is more."</ref> ] has noted that at multiple levels, general relativity exhibits what ] has termed a "strangeness in the proportion" (''i.e''. elements that excite wonderment and surprise). It juxtaposes fundamental concepts (space and time ''versus'' matter and motion) which had previously been considered as entirely independent. Chandrasekhar also noted that Einstein's only guides in his search for an exact theory were the principle of equivalence and his sense that a proper description of gravity should be geometrical at its basis, so that there was an "element of revelation" in the manner in which Einstein arrived at his theory.<ref>{{Harvnb|Chandrasekhar|1984|loc=p. 6}}</ref> Other elements of beauty associated with the general theory of relativity are its simplicity and symmetry, the manner in which it incorporates invariance and unification, and its perfect logical consistency.<ref>{{Harvnb|Engler|2002}}</ref> | |||

| The motion of the observer O in orbit is rather like a ping-pong ball being forced to follow the 'dent' or depression created in a trampoline by a relatively massive object like a medicine ball. The geometry is determined by the medicine ball, the relatively light ping-pong ball causing no significant change in the local geometry. Thus, general relativity provides a simpler and more natural description of gravity than Newton's ] formulation. An oft-quoted analogy used in visualising spacetime curvature is to imagine a universe of one-dimensional beings living in one dimension of space and one dimension of time. Each piece of matter is not a point on any imaginable curved surface, but a ] showing where that point moves as it goes from the past to the future. | |||

| In the preface to '']'', Einstein said "The present book is intended, as far as possible, to give an exact insight into the theory of Relativity to those readers who, from a general scientific and philosophical point of view, are interested in the theory, but who are not conversant with the mathematical apparatus of theoretical physics. The work presumes a standard of education corresponding to that of a university matriculation examination, and, despite the shortness of the book, a fair amount of patience and force of will on the part of the reader. The author has spared himself no pains in his endeavour to present the main ideas in the simplest and most intelligible form, and on the whole, in the sequence and connection in which they actually originated."<ref>{{cite book |title=Relativity – The Special and General Theory |author1=Albert Einstein |edition= |publisher=Read Books Ltd |year=2011 |isbn=978-1-4474-9358-7 |page=4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yhN9CgAAQBAJ}} </ref> | |||

| The precise means of calculating the geometry of spacetime given the matter distribution is encapsulated in ]. | |||

| == From classical mechanics to general relativity == | |||

| === The Equivalence Principle === | |||

| General relativity can be understood by examining its similarities with and departures from classical physics. The first step is the realization that classical mechanics and Newton's law of gravity admit a geometric description. The combination of this description with the laws of special relativity results in a ] derivation of general relativity.<ref>The following exposition re-traces that of {{Harvnb|Ehlers|1973|loc=sec. 1}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|last=Al-Khalili|first=Jim|date=26 March 2021|title=Gravity and Me: The force that shapes our lives|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08kgv7f|access-date=9 April 2021|website=www.bbc.co.uk}}</ref> | |||

| :''(For more detailed information about the equivalence principle, see ])'' | |||

| Inertial reference frames, in which bodies maintain a uniform state of motion unless acted upon by another body, are distinguished from non-inertial frames, in which freely moving bodies have an acceleration deriving from the reference frame itself. | |||

| === Geometry of Newtonian gravity<!--'Einstein's elevator experiment' redirects here--> === | |||

| In non-inertial frames there is a perceived force which is accounted for by the acceleration of the frame, not by the direct influence of other matter. Thus we feel acceleration when cornering on the roads when we use a car as the physical base of our reference frame. Similarly there are ] and ]s when we define reference frames based on rotating matter (such as the ] or a child's roundabout). In Newtonian mechanics, the coriolis and centrifugal forces are regarded as non-physical ones, arising from the use of a rotating reference frame. In General Relativity there is no way, locally, to define these "forces" as distinct from those arising through the use of any non-inertial reference frame. | |||

| ] | |||

| At the base of ] is the notion that a ]'s motion can be described as a combination of free (or ]l) motion, and deviations from this free motion. Such deviations are caused by external forces acting on a body in accordance with Newton's second ], which states that the net ] acting on a body is equal to that body's (inertial) ] multiplied by its ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Arnold|1989|loc=ch. 1}}</ref> The preferred inertial motions are related to the geometry of space and time: in the standard ] of classical mechanics, objects in free motion move along straight lines at constant speed. In modern parlance, their paths are ]s, straight ] in ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Ehlers|1973|pp=5f}}</ref> | |||

| Conversely, one might expect that inertial motions, once identified by observing the actual motions of bodies and making allowances for the external forces (such as ] or ]), can be used to define the geometry of space, as well as a time ]. However, there is an ambiguity once gravity comes into play. According to Newton's law of gravity, and independently verified by experiments such as that of ] and its successors (see ]), there is a universality of free fall (also known as the weak ], or the universal equality of inertial and passive-gravitational mass): the trajectory of a ] in free fall depends only on its position and initial speed, but not on any of its material properties.<ref>{{Harvnb|Will|1993|loc=sec. 2.4}}, {{Harvnb|Will|2006|loc=sec. 2}}</ref> A simplified version of this is embodied in '''Einstein's elevator experiment'''<!--boldface per WP:R#PLA-->, illustrated in the figure on the right: for an observer in an enclosed room, it is impossible to decide, by mapping the trajectory of bodies such as a dropped ball, whether the room is stationary in a gravitational field and the ball accelerating, or in free space aboard a rocket that is accelerating at a rate equal to that of the gravitational field versus the ball which upon release has nil acceleration.<ref>{{Harvnb|Wheeler|1990|loc=ch. 2}}</ref> | |||

| The ] in general relativity states that there is no local experiment to distinguish non-rotating free fall in a gravitational field from uniform motion in the absence of a gravitational field. | |||

| Given the universality of free fall, there is no observable distinction between inertial motion and motion under the influence of the gravitational force. This suggests the definition of a new class of inertial motion, namely that of objects in free fall under the influence of gravity. This new class of preferred motions, too, defines a geometry of space and time—in mathematical terms, it is the geodesic motion associated with a specific ] which depends on the ] of the ]. Space, in this construction, still has the ordinary ]. However, space''time'' as a whole is more complicated. As can be shown using simple thought experiments following the free-fall trajectories of different test particles, the result of transporting spacetime vectors that can denote a particle's velocity (time-like vectors) will vary with the particle's trajectory; mathematically speaking, the Newtonian connection is not ]. From this, one can deduce that spacetime is curved. The resulting ] is a geometric formulation of Newtonian gravity using only ] concepts, i.e. a description which is valid in any desired coordinate system.<ref>{{Harvnb|Ehlers|1973|loc=sec. 1.2}}, {{Harvnb|Havas|1964}}, {{Harvnb|Künzle|1972}}. The simple thought experiment in question was first described in {{Harvnb|Heckmann|Schücking|1959}}</ref> In this geometric description, ]s—the relative acceleration of bodies in free fall—are related to the derivative of the connection, showing how the modified geometry is caused by the presence of mass.<ref>{{Harvnb|Ehlers|1973|pp=10f}}</ref> | |||

| In short there is no gravity in a reference frame in free fall. From this perspective the observed gravity at the surface of the Earth is the force observed in a reference frame defined from matter at the surface which is not free, but is acted on from below by the matter within the Earth, and is analogous to the acceleration felt in a car. | |||

| === Relativistic generalization === | |||

| In the process of discovering GR, Einstein used a fact that was known since the time of Galileo, namely, that the inertial and gravitational masses of an object happen to be the same. He used this as the basis for the ], which describes the effects of gravitation and ] as different perspectives of the same thing (at least locally), and which he stated in ] as: | |||

| ]]] | |||

| As intriguing as geometric Newtonian gravity may be, its basis, classical mechanics, is merely a ] of (special) relativistic mechanics.<ref>Good introductions are, in order of increasing presupposed knowledge of mathematics, {{Harvnb|Giulini|2005}}, {{Harvnb|Mermin|2005}}, and {{Harvnb|Rindler|1991}}; for accounts of precision experiments, cf. part IV of {{Harvnb|Ehlers|Lämmerzahl|2006}}</ref> In the language of ]: where gravity can be neglected, physics is ] as in special relativity rather than ] as in classical mechanics. (The defining symmetry of special relativity is the ], which includes translations, rotations, boosts and reflections.) The differences between the two become significant when dealing with speeds approaching the ], and with high-energy phenomena.<ref>An in-depth comparison between the two symmetry groups can be found in {{Harvnb|Giulini|2006}}</ref> | |||

| With Lorentz symmetry, additional structures come into play. They are defined by the set of light cones (see image). The light-cones define a causal structure: for each ] {{math|A}}, there is a set of events that can, in principle, either influence or be influenced by {{math|A}} via signals or interactions that do not need to travel faster than light (such as event {{math|B}} in the image), and a set of events for which such an influence is impossible (such as event {{math|C}} in the image). These sets are ]-independent.<ref>{{Harvnb|Rindler|1991|loc=sec. 22}}, {{Harvnb|Synge|1972|loc=ch. 1 and 2}}</ref> In conjunction with the world-lines of freely falling particles, the light-cones can be used to reconstruct the spacetime's semi-Riemannian metric, at least up to a positive scalar factor. In mathematical terms, this defines a ]<ref>{{Harvnb|Ehlers|1973|loc=sec. 2.3}}</ref> or conformal geometry. | |||

| :''We shall therefore assume the complete physical equivalence of a gravitational field and the corresponding acceleration of the ]. This assumption extends the principle of ] to the case of uniformly accelerated motion of the reference frame.'' | |||

| Special relativity is defined in the absence of gravity. For practical applications, it is a suitable model whenever gravity can be neglected. Bringing gravity into play, and assuming the universality of free fall motion, an analogous reasoning as in the previous section applies: there are no global ]s. Instead there are approximate inertial frames moving alongside freely falling particles. Translated into the language of spacetime: the straight ] lines that define a gravity-free inertial frame are deformed to lines that are curved relative to each other, suggesting that the inclusion of gravity necessitates a change in spacetime geometry.<ref>{{Harvnb|Ehlers|1973|loc=sec. 1.4}}, {{Harvnb|Schutz|1985|loc=sec. 5.1}}</ref> | |||

| In other words, he postulated that no experiment can locally distinguish between a uniform gravitational field and a uniform acceleration. The meaning of the ''Principle of Equivalence'' has gradually broadened, in consonance with Einstein's further writings, to include the concept that no physical measurement within a given unaccelerated reference system can determine its state of motion. This implies that it is impossible to measure, and therefore virtually meaningless to discuss, changes in fundamental physical constants, such as the ]es or ]s of ] in different states of relative motion. Any measured change in such a constant would represent either experimental error or a demonstration that the theory of relativity was wrong or incomplete. | |||

| A priori, it is not clear whether the new local frames in free fall coincide with the reference frames in which the laws of special relativity hold—that theory is based on the propagation of light, and thus on electromagnetism, which could have a different set of ]s. But using different assumptions about the special-relativistic frames (such as their being earth-fixed, or in free fall), one can derive different predictions for the gravitational redshift, that is, the way in which the frequency of light shifts as the light propagates through a gravitational field (cf. ]). The actual measurements show that free-falling frames are the ones in which light propagates as it does in special relativity.<ref>{{Harvnb|Ehlers|1973|pp=17ff}}; a derivation can be found in {{Harvnb|Mermin|2005|loc=ch. 12}}. For the experimental evidence, cf. the section ], below</ref> The generalization of this statement, namely that the laws of special relativity hold to good approximation in freely falling (and non-rotating) reference frames, is known as the ], a crucial guiding principle for generalizing special-relativistic physics to include gravity.<ref>{{Harvnb|Rindler|2001|loc=sec. 1.13}}; for an elementary account, see {{Harvnb|Wheeler|1990|loc=ch. 2}}; there are, however, some differences between the modern version and Einstein's original concept used in the historical derivation of general relativity, cf. {{Harvnb|Norton|1985}}</ref> | |||

| The equivalence principle explains the experimental observation that inertial and gravitational ] are equivalent. Moreover, the principle implies that some frames of reference must obey a ]: that ] is ] (by matter and energy), and gravity can be seen purely as a result of this ]. This yields many predictions such as gravitational redshifts and light bending around stars, ], time slowed by gravitational fields, and slightly modified laws of gravitation even in weak gravitational fields. However, it should be noted that the equivalence principle does not uniquely determine the field equations of curved spacetime, and there is a parameter known as the ] which can be adjusted. | |||

| The same experimental data shows that time as measured by clocks in a gravitational field—], to give the technical term—does not follow the rules of special relativity. In the language of spacetime geometry, it is not measured by the ]. As in the Newtonian case, this is suggestive of a more general geometry. At small scales, all reference frames that are in free fall are equivalent, and approximately Minkowskian. Consequently, we are now dealing with a curved generalization of Minkowski space. The ] that defines the geometry—in particular, how lengths and angles are measured—is not the Minkowski metric of special relativity, it is a generalization known as a semi- or ] metric. Furthermore, each Riemannian metric is naturally associated with one particular kind of connection, the ], and this is, in fact, the connection that satisfies the equivalence principle and makes space locally Minkowskian (that is, in suitable ], the metric is Minkowskian, and its first partial derivatives and the connection coefficients vanish).<ref>{{Harvnb|Ehlers|1973|loc=sec. 1.4}} for the experimental evidence, see once more section ]. Choosing a different connection with non-zero ] leads to a modified theory known as ]</ref> | |||

| === The Covariance Principle === | |||

| === Einstein's equations === | |||

| Following on from the spirit of special relativity, the ] states that all coordinate systems are equivalent for the formulation of the general laws of nature. Mathematically, this suggests that the laws of physics should be ]. | |||

| {{Main|Einstein field equations|Mathematics of general relativity}} | |||

| Having formulated the relativistic, geometric version of the effects of gravity, the question of gravity's source remains. In Newtonian gravity, the source is mass. In special relativity, mass turns out to be part of a more general quantity called the ], which includes both ] and momentum ] as well as ]: ] and shear.<ref>{{Harvnb|Ehlers|1973|p=16}}, {{Harvnb|Kenyon|1990|loc=sec. 7.2}}, {{Harvnb|Weinberg|1972|loc=sec. 2.8}}</ref> Using the equivalence principle, this tensor is readily generalized to curved spacetime. Drawing further upon the analogy with geometric Newtonian gravity, it is natural to assume that the ] for gravity relates this tensor and the ], which describes a particular class of tidal effects: the change in volume for a small cloud of test particles that are initially at rest, and then fall freely. In special relativity, ]–momentum corresponds to the statement that the energy–momentum tensor is ]-free. This formula, too, is readily generalized to curved spacetime by replacing partial derivatives with their curved-] counterparts, ]s studied in differential geometry. With this additional condition—the covariant divergence of the energy–momentum tensor, and hence of whatever is on the other side of the equation, is zero—the simplest nontrivial set of equations are what are called Einstein's (field) equations: | |||

| {{Equation box 1 | |||

| |indent=: | |||

| |title='''Einstein's field equations''' | |||

| |equation=<math>G_{\mu\nu}\equiv R_{\mu\nu} - {\textstyle 1 \over 2}R\,g_{\mu\nu} = \kappa T_{\mu\nu}\,</math> | |||

| |cellpadding | |||

| |border | |||

| |border colour = #50C878 | |||

| |background colour = #ECFCF4}} | |||

| On the left-hand side is the ], <math>G_{\mu\nu}</math>, which is symmetric and a specific divergence-free combination of the Ricci tensor <math>R_{\mu\nu}</math> and the metric. In particular, | |||

| == Foundations == | |||

| : <math>R=g^{\mu\nu}R_{\mu\nu}</math> | |||

| is the curvature scalar. The Ricci tensor itself is related to the more general ] as | |||

| : <math>R_{\mu\nu}={R^\alpha}_{\mu\alpha\nu}.</math> | |||

| On the right-hand side, <math>\kappa</math> is a constant and <math>T_{\mu\nu}</math> is the energy–momentum tensor. All tensors are written in ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Ehlers|1973|pp=19–22}}; for similar derivations, see sections 1 and 2 of ch. 7 in {{Harvnb|Weinberg|1972}}. The Einstein tensor is the only divergence-free tensor that is a function of the metric coefficients, their first and second derivatives at most, and allows the spacetime of special relativity as a solution in the absence of sources of gravity, cf. {{Harvnb|Lovelock|1972}}. The tensors on both side are of second rank, that is, they can each be thought of as 4×4 matrices, each of which contains ten independent terms; hence, the above represents ten coupled equations. The fact that, as a consequence of geometric relations known as ], the Einstein tensor satisfies a further four identities reduces these to six independent equations, e.g. {{Harvnb|Schutz|1985|loc=sec. 8.3}}</ref> Matching the theory's prediction to observational results for ]ary ]s or, equivalently, assuring that the weak-gravity, low-speed limit is Newtonian mechanics, the proportionality constant <math>\kappa</math> is found to be <math display="inline">\kappa=\frac{8\pi G}{c^4}</math>, where <math>G</math> is the ] and <math>c</math> the speed of light in vacuum.<ref>{{Harvnb|Kenyon|1990|loc=sec. 7.4}}</ref> When there is no matter present, so that the energy–momentum tensor vanishes, the results are the vacuum Einstein equations, | |||

| General relativity's mathematical foundations go back to the ]s of ] and the many attempts over the centuries to prove ]'s ], that parallel lines remain always equidistant, culminating with the realisation by ], ] and ] that this postulate need not be true. It is an eternal monument to Euclid's genius that he classified this principle as a ''postulate'' and not as an ''axiom''. The general mathematics of ] was developed by Gauss' student, ], but these were thought to be mostly inapplicable to the real world until Einstein developed his theory of relativity. The existing applications were restricted to the geometry of curved surfaces in Euclidean space, as if one lived and moved in such a surface, and to the mechanics of deformable bodies. While such applications seem trivial compared to the calculations in the four dimensional spacetimes of general relativity, they provided a minimal development and test environment for some of the equations. | |||

| : <math>R_{\mu\nu}=0.</math> | |||

| In general relativity, the ] of a particle free from all external, non-gravitational force is a particular type of geodesic in curved spacetime. In other words, a freely moving or falling particle always moves along a geodesic. | |||

| Gauss had realised that there is no '']'' reason for the geometry of space to be Euclidean. This means that if a physicist holds up a stick, and a cartographer stands some distance away and measures its length by a triangulation technique based on Euclidean geometry, then he is not guaranteed to get the same answer as if the physicist brings the stick to him and he measures its length directly. Of course, for a stick he could not in practice measure the difference between the two measurements, but there are equivalent measurements which do detect the non-Euclidean geometry of space-time directly; for example the Pound-Rebka experiment (]) detected the change in wavelength of light from a ] source rising 22.5 meters against gravity in a shaft in the Jefferson Physical Laboratory at ], and the rate of ]s in ] ]s orbiting the Earth has to be corrected for the effect of gravity. | |||

| The ] is: | |||

| ]'s theory of gravity had assumed that objects had absolute velocities: that some things ''really'' were at rest while others ''really'' were in motion. He realized, and made clear, that there was no way these absolutes could be measured. All the measurements one can make provide only velocities relative to one's own velocity (positions relative to one's own position, and so forth), and all the laws of mechanics would appear to operate identically no matter how one was moving. Newton believed, however, that the theory could not be made sense of without presupposing that there ''are'' absolute values, even if they cannot be experimental error or a demonstration that the theory of relativity was wrong or incomplete. | |||

| : <math> {d^2 x^\mu \over ds^2}+\Gamma^\mu {}_{\alpha \beta}{d x^\alpha \over ds}{d x^\beta \over ds}=0,</math> | |||

| where <math>s</math> is a scalar parameter of motion (e.g. the ]), and <math> \Gamma^\mu {}_{\alpha \beta}</math> are ] (sometimes called the ] coefficients or ] coefficients) which is symmetric in the two lower indices. Greek indices may take the values: 0, 1, 2, 3 and the ] is used for repeated indices <math>\alpha</math> and <math>\beta</math>. The quantity on the left-hand-side of this equation is the acceleration of a particle, and so this equation is analogous to ] which likewise provide formulae for the acceleration of a particle. This equation of motion employs the ], meaning that repeated indices are summed (i.e. from zero to three). The Christoffel symbols are functions of the four spacetime coordinates, and so are independent of the velocity or acceleration or other characteristics of a ] whose motion is described by the geodesic equation. | |||

| === Total force in general relativity === | |||

| {{See also|Two-body problem in general relativity}} | |||

| In general relativity, the effective ] of an object of mass ''m'' revolving around a massive central body ''M'' is given by<ref>{{cite book |title=Gravitation and Cosmology: Principles and Applications of the General Theory of Relativity|last=Weinberg, Steven|publisher=John Wiley|year=1972|isbn=978-0-471-92567-5}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Relativity, Gravitation and Cosmology: a Basic Introduction|last=Cheng, Ta-Pei|publisher=Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press|year=2005|isbn=978-0-19-852957-6}}</ref> | |||

| :<math>U_f(r) =-\frac{GMm}{r}+\frac{L^{2}}{2mr^{2}}-\frac{GML^{2}}{mc^{2}r^{3}}</math> | |||

| == Predictions of GR == | |||

| :''(For more detailed information about tests and predictions of general relativity, see ])'' | |||

| Like any good ], general relativity makes predictions which can be tested. Some of the predictions of general relativity include the perihelion shifts of planetary orbits (particularly that of ]), bending of light by massive objects, and the existence of gravitational waves. The first two of these tests have been verified to a high degree of accuracy and precision. Most researchers believe in the existence of gravitational waves, but more accurate experiments are needed to raise this prediction to the status of the other two, if one demands direct detection of the waves. Nevertheless, indirect effects of gravitational wave emission have been observed for a binary system of orbiting neutron stars, as described in ]. | |||

| A conservative total ] can then be obtained as its ] | |||

| Other predictions include the ], the existence of ] and possibly the existence of ]s. The existence of black holes is generally accepted, but the existence of wormholes is still very controversial, many researchers believing that wormholes may exist only in the presence of ]. The existence of ] is very speculative, as they appear to contradict the second law of thermodynamics. | |||

| :<math>F_f(r)=-\frac{GMm}{r^{2}}+\frac{L^{2}}{mr^{3}}-\frac{3GML^{2}}{mc^{2}r^{4}}</math> | |||

| Many other quantitative predictions of general relativity have since been confirmed by astronomical observations. One of the most recent, the discovery in ] of ], a binary ] in which one component is a ] and where the ] ] 16.88° per year (or about 140,000 times faster than the precession of Mercury's perihelion), enabled the most precise experimental verification yet of the effects predicted by general relativity. . | |||

| where ''L'' is the ]. The first term represents the ], which is described by the inverse-square law. The second term represents the ] in the circular motion. The third term represents the relativistic effect. | |||

| == Mathematics of GR == | |||

| :''(For more detailed information about the mathematics of general relativity, see ])'' | |||

| The idea of curvature can be clarified by the following considerations. While it can be helpful for visualization to imagine a curved surface sitting in a space of higher dimension, this model is not very useful for the real universe; although a two dimensional surface can be embedded in three, and thus visualized well, a curved four dimensional spacetime such as our universe cannot be imbedded in a flat space of even five dimensions, but many more are required. Curvature can be measured entirely within a surface, and similarly within a higher-dimensional ] such as space or spacetime. On Earth, if you start at the North Pole, walk south for about 10,000 km (to the Equator), turn left by 90 degrees, walk for 10,000 more km, and then do the same again (walk for 10,000 more km, turn left by 90 degrees, walk for 10,000 more km), you will be back where you started. Such a triangle with three right angles is only possible because the surface of the earth is curved. The curvature of spacetime can be evaluated, and indeed given meaning, in a similar way. Curvature may be quantified by the ], essentially a matrix of numbers which describes how a vector that is moved along a curve parallel to itself changes when a round trip is made. In flat space, the vector returns to the same orientation, but in a curved space it generally does not. In spaces of two dimensions, the Riemann tensor is a <math>1 \times 1</math> matrix (i.e., just a number) called the Gaussian or ]. | |||

| == |

=== Alternatives to general relativity === | ||

| {{Main|Alternatives to general relativity}} | |||

| There are ] built upon the same premises, which include additional rules and/or constraints, leading to different field equations. Examples are ], ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Brans|Dicke|1961}}, {{Harvnb|Weinberg|1972|loc=sec. 3 in ch. 7}}, {{Harvnb|Goenner|2004|loc=sec. 7.2}}, and {{Harvnb|Trautman|2006}}, respectively</ref> | |||

| == Definition and basic applications == | |||

| {{See also|Mathematics of general relativity|Physical theories modified by general relativity}} | |||

| The derivation outlined in the previous section contains all the information needed to define general relativity, describe its key properties, and address a question of crucial importance in physics, namely how the theory can be used for model-building. | |||

| In ], all ] are referred to a ]. A reference frame is defined by choosing particular matter as the basis for its definition. Thus, all motion is defined and quantified relative to other matter. In the special theory of relativity it is assumed that ] can be extended indefinitely in all directions in space and time. The theory of special relativity concerns itself with reference frames that move at a constant velocity with respect to each other (i.e. ]), whereas general relativity deals with all frames of reference. In the general theory it is recognised that we can only define local frames to given accuracy for finite time periods and finite regions of space (similarly we can draw flat maps of regions of the surface of the earth but we cannot extend them to cover the whole surface without distortion). In general relativity ]'s laws are assumed to hold in ]. | |||

| === Definition and basic properties === | |||

| The ] (]) modified the equations used in comparing the measurements made by differently moving bodies, in view of the constant value of the ], i.e. its observed ] in ]s moving uniformly relative to each other. This had the consequence that physics could no longer treat ] and ] separately, but only as a single four-dimensional system, "space-time," which was divided into "time-like" and "space-like" directions differently depending on the observer's motion. The general theory added to this that the presence of matter "warped" the local space-time environment, so that apparently "straight" lines through space and time have the properties we think of "curved" lines as having. | |||

| General relativity is a ] theory of gravitation. At its core are ], which describe the relation between the geometry of a four-dimensional ] representing spacetime, and the ] contained in that spacetime.<ref>{{Harvnb|Wald|1984|loc=ch. 4}}, {{Harvnb|Weinberg|1972|loc=ch. 7}} or, in fact, any other textbook on general relativity</ref> Phenomena that in classical mechanics are ascribed to the action of the force of gravity (such as ], orbital motion, and ] ]), correspond to inertial motion within a curved geometry of spacetime in general relativity; there is no gravitational force deflecting objects from their natural, straight paths. Instead, gravity corresponds to changes in the properties of space and time, which in turn changes the straightest-possible paths that objects will naturally follow.<ref>At least approximately, cf. {{Harvnb|Poisson|2004a}}</ref> The curvature is, in turn, caused by the energy–momentum of matter. Paraphrasing the relativist ], spacetime tells matter how to move; matter tells spacetime how to curve.<ref>{{Harvnb|Wheeler|1990|p=xi}}</ref> | |||

| While general relativity replaces the ] gravitational potential of classical physics by a symmetric ]-two ], the latter reduces to the former in certain ]. For ] and ] relative to the speed of light, the theory's predictions converge on those of Newton's law of universal gravitation.<ref>{{Harvnb|Wald|1984|loc=sec. 4.4}}</ref> | |||

| Thus Newton's first law is replaced by the law of geodesic motion. | |||

| As it is constructed using tensors, general relativity exhibits ]: its laws—and further laws formulated within the general relativistic framework—take on the same form in all ]s.<ref>{{Harvnb|Wald|1984|loc=sec. 4.1}}</ref> Furthermore, the theory does not contain any invariant geometric background structures, i.e. it is ]. It thus satisfies a more stringent ], namely that the ] are the same for all observers.<ref>For the (conceptual and historical) difficulties in defining a general principle of relativity and separating it from the notion of general covariance, see {{Harvnb|Giulini|2007}}</ref> ], as expressed in the equivalence principle, spacetime is ], and the laws of physics exhibit ].<ref>section 5 in ch. 12 of {{Harvnb|Weinberg|1972}}</ref> | |||

| There are no known experimental results that suggest that a theory of gravity radically different from general relativity is necessary. For example, the ] was initially speculated to demonstrate "gravitational shielding," but was subsequently explained by conventional phenomena. | |||

| === Model-building === | |||

| === Quantum mechanics and general relativity === | |||

| The core concept of general-relativistic model-building is that of a ]. Given both Einstein's equations and suitable equations for the properties of matter, such a solution consists of a specific semi-] (usually defined by giving the metric in specific coordinates), and specific matter fields defined on that manifold. Matter and geometry must satisfy Einstein's equations, so in particular, the matter's energy–momentum tensor must be divergence-free. The matter must, of course, also satisfy whatever additional equations were imposed on its properties. In short, such a solution is a model universe that satisfies the laws of general relativity, and possibly additional laws governing whatever matter might be present.<ref>Introductory chapters of {{Harvnb|Stephani|Kramer|MacCallum|Hoenselaers|2003}}</ref> | |||

| Einstein's equations are nonlinear partial differential equations and, as such, difficult to solve exactly.<ref>A review showing Einstein's equation in the broader context of other PDEs with physical significance is {{Harvnb|Geroch|1996}}</ref> Nevertheless, a number of ] are known, although only a few have direct physical applications.<ref>For background information and a list of solutions, cf. {{Harvnb|Stephani|Kramer|MacCallum|Hoenselaers|2003}}; a more recent review can be found in {{Harvnb|MacCallum|2006}}</ref> The best-known exact solutions, and also those most interesting from a physics point of view, are the ], the ] and the ], each corresponding to a certain type of black hole in an otherwise empty universe,<ref>{{Harvnb|Chandrasekhar|1983|loc=ch. 3,5,6}}</ref> and the ] and ]s, each describing an expanding cosmos.<ref>{{Harvnb|Narlikar|1993|loc=ch. 4, sec. 3.3}}</ref> Exact solutions of great theoretical interest include the ] (which opens up the intriguing possibility of ] in curved spacetimes), the ] (a model universe that is ], but ]), and ] (which has recently come to prominence in the context of what is called the ]).<ref>Brief descriptions of these and further interesting solutions can be found in {{Harvnb|Hawking|Ellis|1973|loc=ch. 5}}</ref> | |||

| There are good theoretical reasons for considering general relativity to be incomplete. General relativity does not include ], and this causes the theory to break down at sufficiently high energies. A continuing unsolved challenge of modern physics is the question of how to correctly combine general relativity with ], thus applying it also to the smallest scales of time and space. | |||

| Given the difficulty of finding exact solutions, Einstein's field equations are also solved frequently by ] on a computer, or by considering small perturbations of exact solutions. In the field of ], powerful computers are employed to simulate the geometry of spacetime and to solve Einstein's equations for interesting situations such as two colliding black holes.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lehner|2002}}</ref> In principle, such methods may be applied to any system, given sufficient computer resources, and may address fundamental questions such as ]. Approximate solutions may also be found by ] such as ]<ref>For instance {{Harvnb|Wald|1984|loc=sec. 4.4}}</ref> and its generalization, the ], both of which were developed by Einstein. The latter provides a systematic approach to solving for the geometry of a spacetime that contains a distribution of matter that moves slowly compared with the speed of light. The expansion involves a series of terms; the first terms represent Newtonian gravity, whereas the later terms represent ever smaller corrections to Newton's theory due to general relativity.<ref>{{Harvnb|Will|1993|loc=sec. 4.1 and 4.2}}</ref> An extension of this expansion is the parametrized post-Newtonian (PPN) formalism, which allows quantitative comparisons between the predictions of general relativity and alternative theories.<ref>{{Harvnb|Will|2006|loc=sec. 3.2}}, {{Harvnb|Will|1993|loc=ch. 4}}</ref> | |||

| === Other theories === | |||

| == Consequences of Einstein's theory == | |||

| The ] and the ] are modifications of general relativity and cannot be ruled out by current experiments. | |||

| General relativity has a number of physical consequences. Some follow directly from the theory's axioms, whereas others have become clear only in the course of many years of research that followed Einstein's initial publication. | |||

| === Gravitational time dilation and frequency shift === | |||

| There have been attempts to formulate consistent theories which combine gravity and electromagnetism, some of the first being the ] and ]. | |||

| {{Main|Gravitational time dilation}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Assuming that the equivalence principle holds,<ref>{{Harvnb|Rindler|2001|pp=24–26 vs. pp. 236–237}} and {{Harvnb|Ohanian|Ruffini|1994|pp=164–172}}. Einstein derived these effects using the equivalence principle as early as 1907, cf. {{Harvnb|Einstein|1907}} and the description in {{Harvnb|Pais|1982|pp=196–198}}</ref> gravity influences the passage of time. Light sent down into a ] is ]ed, whereas light sent in the opposite direction (i.e., climbing out of the gravity well) is ]ed; collectively, these two effects are known as the gravitational frequency shift. More generally, processes close to a massive body run more slowly when compared with processes taking place farther away; this effect is known as gravitational time dilation.<ref>{{Harvnb|Rindler|2001|pp=24–26}}; {{Harvnb|Misner|Thorne|Wheeler|1973 |loc=§ 38.5}}</ref> | |||

| Gravitational redshift has been measured in the laboratory<ref>], see {{Harvnb|Pound|Rebka|1959}}, {{Harvnb|Pound|Rebka|1960}}; {{Harvnb|Pound|Snider|1964}}; a list of further experiments is given in {{Harvnb|Ohanian|Ruffini|1994|loc=table 4.1 on p. 186}}</ref> and using astronomical observations.<ref>{{Harvnb|Greenstein|Oke|Shipman|1971}}; the most recent and most accurate Sirius B measurements are published in {{Harvnb|Barstow, Bond et al.|2005}}.</ref> Gravitational time dilation in the Earth's gravitational field has been measured numerous times using ],<ref>Starting with the ], {{Harvnb|Hafele|Keating|1972a}} and {{Harvnb|Hafele|Keating|1972b}}, and culminating in the ] experiment; an overview of experiments can be found in {{Harvnb|Ohanian|Ruffini|1994|loc=table 4.1 on p. 186}}</ref> while ongoing validation is provided as a side effect of the operation of the ] (GPS).<ref>GPS is continually tested by comparing atomic clocks on the ground and aboard orbiting satellites; for an account of relativistic effects, see {{Harvnb|Ashby|2002}} and {{Harvnb|Ashby|2003}}</ref> Tests in stronger gravitational fields are provided by the observation of ]s.<ref>{{Harvnb|Stairs|2003}} and {{Harvnb|Kramer|2004}}</ref> All results are in agreement with general relativity.<ref>General overviews can be found in section 2.1. of Will 2006; Will 2003, pp. 32–36; {{Harvnb|Ohanian|Ruffini|1994|loc=sec. 4.2}}</ref> However, at the current level of accuracy, these observations cannot distinguish between general relativity and other theories in which the equivalence principle is valid.<ref>{{Harvnb|Ohanian|Ruffini|1994|pp=164–172}}</ref> | |||

| === Light deflection and gravitational time delay === | |||

| ==Nonlinearity of the field equations == | |||

| {{Main|Schwarzschild geodesics|Kepler problem in general relativity|Gravitational lens|Shapiro delay}} | |||

| ] | |||

| General relativity predicts that the path of light will follow the curvature of spacetime as it passes near a massive object. This effect was initially confirmed by observing the light of stars or distant quasars being deflected as it passes the ].<ref>Cf. {{Harvnb|Kennefick|2005}} for the classic early measurements by Arthur Eddington's expeditions. For an overview of more recent measurements, see {{Harvnb|Ohanian|Ruffini|1994|loc=ch. 4.3}}. For the most precise direct modern observations using quasars, cf. {{Harvnb|Shapiro|Davis|Lebach|Gregory|2004}}</ref> | |||

| This and related predictions follow from the fact that light follows what is called a light-like or ]—a generalization of the straight lines along which light travels in classical physics. Such geodesics are the generalization of the ] of lightspeed in special relativity.<ref>This is not an independent axiom; it can be derived from Einstein's equations and the Maxwell ] using a ], cf. {{Harvnb|Ehlers|1973|loc=sec. 5}}</ref> As one examines suitable model spacetimes (either the exterior Schwarzschild solution or, for more than a single mass, the post-Newtonian expansion),<ref>{{Harvnb|Blanchet|2006|loc=sec. 1.3}}</ref> several effects of gravity on light propagation emerge. Although the bending of light can also be derived by extending the universality of free fall to light,<ref>{{Harvnb|Rindler|2001|loc=sec. 1.16}}; for the historical examples, {{Harvnb|Israel|1987|pp=202–204}}; in fact, Einstein published one such derivation as {{Harvnb|Einstein|1907}}. Such calculations tacitly assume that the geometry of space is ], cf. {{Harvnb|Ehlers|Rindler|1997}}</ref> the angle of deflection resulting from such calculations is only half the value given by general relativity.<ref>From the standpoint of Einstein's theory, these derivations take into account the effect of gravity on time, but not its consequences for the warping of space, cf. {{Harvnb|Rindler|2001|loc=sec. 11.11}}</ref> | |||

| The field equations of general relativity are a set of nonlinear partial differential equations for the metric. As such, this distinguishes the field equations of general relativity from some of the other important ] in physics, such as ] (which are linear in the electric and magnetic fields) and ] (which is linear in the wavefunction). | |||

| Closely related to light deflection is the Shapiro Time Delay, the phenomenon that light signals take longer to move through a gravitational field than they would in the absence of that field. There have been numerous successful tests of this prediction.<ref>For the Sun's gravitational field using radar signals reflected from planets such as ] and Mercury, cf. {{Harvnb|Shapiro|1964}}, {{Harvnb|Weinberg|1972|loc=ch. 8, sec. 7}}; for signals actively sent back by space probes (] measurements), cf. {{Harvnb|Bertotti|Iess|Tortora|2003}}; for an overview, see {{Harvnb|Ohanian|Ruffini|1994|loc=table 4.4 on p. 200}}; for more recent measurements using signals received from a ] that is part of a binary system, the gravitational field causing the time delay being that of the other pulsar, cf. {{Harvnb|Stairs|2003|loc=sec. 4.4}}</ref> In the ] (PPN), measurements of both the deflection of light and the gravitational time delay determine a parameter called γ, which encodes the influence of gravity on the geometry of space.<ref>{{Harvnb|Will|1993|loc=sec. 7.1 and 7.2}}</ref> | |||

| == History == | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| === Gravitational waves === | |||

| <!-- This section should be compressed once the proposed full article is created. For example, the discussion about Einstein's "famous goof" should be moved to that article, as well as the math in this section. --> | |||

| {{Main|Gravitational wave}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Predicted in 1916<ref>{{cite journal|author=Einstein, A|title=Näherungsweise Integration der Feldgleichungen der Gravitation|date=22 June 1916|url=http://einstein-annalen.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/related_texts/sitzungsberichte|journal=]|issue=part 1|pages=688–696|bibcode=1916SPAW.......688E|access-date=12 February 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190321062928/http://einstein-annalen.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/related_texts/sitzungsberichte|archive-date=21 March 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|author=Einstein, A|title=Über Gravitationswellen|date=31 January 1918|url=http://einstein-annalen.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/related_texts/sitzungsberichte|journal=Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften Berlin|issue=part 1|pages=154–167|bibcode=1918SPAW.......154E|access-date=12 February 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190321062928/http://einstein-annalen.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/related_texts/sitzungsberichte|archive-date=21 March 2019}}</ref> by Albert Einstein, there are gravitational waves: ripples in the metric of spacetime that propagate at the speed of light. These are one of several analogies between weak-field gravity and electromagnetism in that, they are analogous to ]s. On 11 February 2016, the Advanced LIGO team announced that they had ] from a ] of black holes ].<ref name="Discovery 2016">{{cite journal |title=Einstein's gravitational waves found at last |journal=Nature News| url=http://www.nature.com/news/einstein-s-gravitational-waves-found-at-last-1.19361 |date=11 February 2016 |last1= Castelvecchi |first1=Davide |last2=Witze |first2=Witze |doi=10.1038/nature.2016.19361 |s2cid=182916902|access-date= 11 February 2016 }}</ref><ref name="Abbot">{{cite journal |title=Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger| author1=B. P. Abbott |collaboration=LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration| journal=Physical Review Letters| year=2016| volume=116|issue=6| doi= 10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.061102 | pmid=26918975| page=061102|arxiv = 1602.03837 |bibcode = 2016PhRvL.116f1102A | s2cid=124959784 }}</ref><ref name="NSF">{{cite web|title = Gravitational waves detected 100 years after Einstein's prediction |website= NSF – National Science Foundation|url = https://www.nsf.gov/news/news_summ.jsp?cntn_id=137628 |date = 11 February 2016}}</ref> | |||

| The simplest type of such a wave can be visualized by its action on a ring of freely floating particles. A sine wave propagating through such a ring towards the reader distorts the ring in a characteristic, rhythmic fashion (animated image to the right).<ref>Most advanced textbooks on general relativity contain a description of these properties, e.g. {{Harvnb|Schutz|1985|loc=ch. 9}}</ref> Since Einstein's equations are ], arbitrarily strong gravitational waves do not obey ], making their description difficult. However, linear approximations of gravitational waves are sufficiently accurate to describe the exceedingly weak waves that are expected to arrive here on Earth from far-off cosmic events, which typically result in relative distances increasing and decreasing by <math>10^{-21}</math> or less. Data analysis methods routinely make use of the fact that these linearized waves can be ].<ref>For example {{Harvnb|Jaranowski|Królak|2005}}</ref> | |||

| ''Full article: ]''<br> | |||

| ''See also: ]'' | |||

| Some exact solutions describe gravitational waves without any approximation, e.g., a wave train traveling through empty space<ref>{{Harvnb|Rindler|2001|loc=ch. 13}}</ref> or ]s, varieties of an expanding cosmos filled with gravitational waves.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gowdy|1971}}, {{Harvnb|Gowdy|1974}}</ref> But for gravitational waves produced in astrophysically relevant situations, such as the merger of two black holes, numerical methods are presently the only way to construct appropriate models.<ref>See {{Harvnb|Lehner|2002}} for a brief introduction to the methods of numerical relativity, and {{Harvnb|Seidel|1998}} for the connection with gravitational wave astronomy</ref> | |||

| The development of '''general relativity''' began in ] with the publication of an article by Einstein on acceleration under special relativity. In that article, he argued that ] is really inertial motion, and that for a freefalling observer the rules of special relativity must apply. This argument is called the ]. Einstein also predicted the existance of ] in the 1907 article. In ], Einstein published another article expanding on the 1907 article, in which additional effects such as the ] by massive bodies were predicted. | |||

| === Orbital effects and the relativity of direction === | |||

| By 1912, Einstein was actively seeking a theory in which gravitation was explained as a geometric phenomenon. At the urging of ], Einstein started by exploring the use of general covariance (which is essentially the use of curvature ]) to create a gravitational theory. However, in ] Einstein abandoned that approach, arguing that it is inconsistent based on the "]". In 1914 and much of 1915, Einstein was trying to create field equations based on another approach. When that approach was proven to be inconsistent, Einstein revisited the concept of general covariance and discovered that the hole argument was flawed. Realizing that general covariance was tenable, Einstein quickly completed the development of the field equations that are named after him. | |||

| {{Main|Two-body problem in general relativity}} | |||

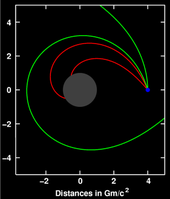

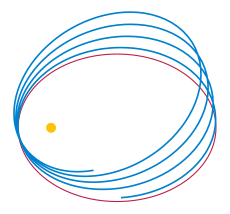

| General relativity differs from classical mechanics in a number of predictions concerning orbiting bodies. It predicts an overall rotation (]) of planetary orbits, as well as orbital decay caused by the emission of gravitational waves and effects related to the relativity of direction. | |||

| ==== Precession of apsides ==== | |||

| In this final phase, Einstein made one famous goof. In October of 1914, Einstein published field equations that were | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Main|Apsidal precession}} | |||

| In general relativity, the ] of any orbit (the point of the orbiting body's closest approach to the system's ]) will ]; the orbit is not an ], but akin to an ellipse that rotates on its focus, resulting in a ]-like shape (see image). Einstein first derived this result by using an approximate metric representing the Newtonian limit and treating the orbiting body as a ]. For him, the fact that his theory gave a straightforward explanation of Mercury's anomalous perihelion shift, discovered earlier by ] in 1859, was important evidence that he had at last identified the correct form of the gravitational field equations.<ref>{{Harvnb|Schutz|2003|pp=48–49}}, {{Harvnb|Pais|1982|pp=253–254}}</ref> | |||

| <math>R_{\mu\nu} = T_{\mu\nu}</math>. | |||

| The effect can also be derived by using either the exact Schwarzschild metric (describing spacetime around a spherical mass)<ref>{{Harvnb|Rindler|2001|loc=sec. 11.9}}</ref> or the much more general ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Will|1993|pp=177–181}}</ref> It is due to the influence of gravity on the geometry of space and to the contribution of ] to a body's gravity (encoded in the ] of Einstein's equations).<ref>In consequence, in the parameterized post-Newtonian formalism (PPN), measurements of this effect determine a linear combination of the terms β and γ, cf. {{Harvnb|Will|2006|loc=sec. 3.5}} and {{Harvnb|Will|1993|loc=sec. 7.3}}</ref> Relativistic precession has been observed for all planets that allow for accurate precession measurements (Mercury, Venus, and Earth),<ref>The most precise measurements are ] measurements of planetary positions; see {{Harvnb|Will|1993|loc=ch. 5}}, {{Harvnb|Will|2006|loc=sec. 3.5}}, {{Harvnb|Anderson|Campbell|Jurgens|Lau|1992}}; for an overview, {{Harvnb|Ohanian|Ruffini|1994|pp=406–407}}</ref> as well as in binary pulsar systems, where it is larger by five ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Kramer|Stairs|Manchester|McLaughlin|2006}}</ref> | |||

| These field equations predicted the non-Newtonian perihelion precession of Mercury, and so had Einstein very excited. However, it was soon realized that they were inconsistent with the local conservation of energy-momentum unless the universe had of a constant density of mass-energy-momentum. In other words, air, rock, and even vacuum should all have the same density! This inconsistency with observation sent Einstein back to the drawing board. However, the solution was all but obvious, and in November of 1915 Einstein published the actual Einstein field equations: | |||

| In general relativity the perihelion shift <math>\sigma</math>, expressed in radians per revolution, is approximately given by{{sfn|Dediu|Magdalena|Martín-Vide|2015|p=}} | |||

| <math>R_{\mu\nu} - (1/2)R g_{\mu\nu} = T_{\mu\nu}</math>. | |||

| :<math>\sigma=\frac {24\pi^3L^2} {T^2c^2(1-e^2)} \ ,</math> | |||

| With the publication of the field equations, the issue became one of solving them for various cases and interpreting the solutions. This and experimental verification have dominated '''general relativity''' research ever since. | |||

| where: | |||

| Since the field equations are non-linear, Einstein assumed that they were insolvable. He was disabused of this notion in ], when ] sent him an exact solution for the case of a spherically symmetric spacetime surrounding a massive object in spherical coordinates. This is now known as the ]. Since then many other exact solutions have been found. | |||

| *<math>L</math> is the ] | |||

| *<math>T</math> is the ] | |||

| *<math>c</math> is the speed of light in vacuum | |||

| *<math>e</math> is the ] | |||

| ==== Orbital decay ==== | |||

| The expansion of the universe created an interesting episode for general relativity. In ], ] found a solution in which the universe may expand or contract, and later ] derived a solution for an expanding universe. Einstein did not believe in an expanding universe, and so he once again edited the field equations, adding in a ] Λ. The revised field equations were | |||

| <!--This subsection is linked to from the subsection Gravitational Waves in Astrophysical Applications, please do not change its title --> | |||

| ]), tracked over 16 years (2021).<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last1=Kramer|first1=M.|last2=Stairs|first2=I. H.|last3=Manchester|first3=R. N.|last4=Wex|first4=N.|last5=Deller|first5=A. T.|last6=Coles|first6=W. A.|last7=Ali|first7=M.|last8=Burgay|first8=M.|last9=Camilo|first9=F.|last10=Cognard|first10=I.|last11=Damour|first11=T.|date=13 December 2021|title=Strong-Field Gravity Tests with the Double Pulsar|url=https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevX.11.041050|journal=Physical Review X|language=en|volume=11|issue=4|page=041050|doi=10.1103/PhysRevX.11.041050|arxiv=2112.06795|bibcode=2021PhRvX..11d1050K|s2cid=245124502|issn=2160-3308}}</ref>]] | |||

| <math>R_{\mu\nu} - (1/2)R g_{\mu\nu} + \Lambda g_{\mu\nu} = T_{\mu\nu}</math>. | |||

| According to general relativity, a ] will emit gravitational waves, thereby losing energy. Due to this loss, the distance between the two orbiting bodies decreases, and so does their orbital period. Within the ] or for ordinary ]s, the effect is too small to be observable. This is not the case for a close binary pulsar, a system of two orbiting ]s, one of which is a ]: from the pulsar, observers on Earth receive a regular series of radio pulses that can serve as a highly accurate clock, which allows precise measurements of the orbital period. Because neutron stars are immensely compact, significant amounts of energy are emitted in the form of gravitational radiation.<ref>{{Harvnb|Stairs|2003}}, {{Harvnb|Schutz|2003|pp=317–321}}, {{Harvnb|Bartusiak|2000|pp=70–86}}</ref> | |||

| This permitted the creation of steady-state solutions, but they were notorious for being unstable: the slightest deviation from an ideal state would still result in the universe expanding or contracting. In ], ] found evidence for the idea that the universe is expanding. This resulted in Einstein dropping the Cosmological constant, referring to it as "the biggest blunder in my career". | |||

| The first observation of a decrease in orbital period due to the emission of gravitational waves was made by ] and ], using the binary pulsar ] they had discovered in 1974. This was the first detection of gravitational waves, albeit indirect, for which they were awarded the 1993 ] in physics.<ref>{{Harvnb|Weisberg|Taylor|2003}}; for the pulsar discovery, see {{Harvnb|Hulse|Taylor|1975}}; for the initial evidence for gravitational radiation, see {{Harvnb|Taylor|1994}}</ref> Since then, several other binary pulsars have been found, in particular the double pulsar ], where both stars are pulsars<ref>{{Harvnb|Kramer|2004}}</ref> and which was last reported to also be in agreement with general relativity in 2021 after 16 years of observations.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| Progress in solving the field equations and understanding the solutions has been ongoing. The solution for a spherically symmetric charged object was discovered by Reissner and later rediscovered by Nordström, and is called the ] solution. The black hole aspect of the Schwarzschild solution was very controversial, and Einstein did not beleive it. However, in ] (two years after Einstein's death in ]), Kruskal published a proof that black holes are called for by the Schwarzschild Solution. Additionally, the solution for a rotating massive object was obtained by ] in the 1960's as is called the ]. The ] for a rotating, charged massive object was published a few years later. | |||

| ==== Geodetic precession and frame-dragging ==== | |||

| Observationally, general relativity has a history too. The perihelion precession of Mercury was the first evidence that general relativity is correct. Eddington's 1919 expedition in which he confirmed Einstein's prediction for the deflection of light by the Sun helped to cement the status of general relativity as a likely true theory. Since then many observations have confirmed the correctness of '''general relativity'''. These include studies of binary pulsars, observations of radio signals passing the limb of the Sun, and even the ] system. For more information, see the ] article. | |||

| {{Main|Geodetic precession|Frame dragging}} | |||

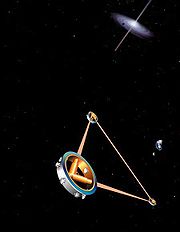

| Several relativistic effects are directly related to the relativity of direction.<ref>{{Harvnb|Penrose|2004|loc=§ 14.5}}, {{Harvnb|Misner|Thorne|Wheeler|1973|loc=§ 11.4}}</ref> One is ]: the axis direction of a ] in free fall in curved spacetime will change when compared, for instance, with the direction of light received from distant stars—even though such a gyroscope represents the way of keeping a direction as stable as possible ("]").<ref>{{Harvnb|Weinberg|1972|loc=sec. 9.6}}, {{Harvnb|Ohanian|Ruffini|1994|loc=sec. 7.8}}</ref> For the Moon–Earth system, this effect has been measured with the help of ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Bertotti|Ciufolini|Bender|1987}}, {{Harvnb|Nordtvedt|2003}}</ref> More recently, it has been measured for test masses aboard the satellite ] to a precision of better than 0.3%.<ref>{{Harvnb|Kahn|2007}}</ref><ref>A mission description can be found in {{Harvnb|Everitt|Buchman|DeBra|Keiser|2001}}; a first post-flight evaluation is given in {{Harvnb|Everitt|Parkinson|Kahn|2007}}; further updates will be available on the mission website {{Harvnb|Kahn|1996–2012}}.</ref> | |||

| Near a rotating mass, there are gravitomagnetic or ] effects. A distant observer will determine that objects close to the mass get "dragged around". This is most extreme for ] where, for any object entering a zone known as the ], rotation is inevitable.<ref>{{Harvnb|Townsend|1997|loc=sec. 4.2.1}}, {{Harvnb|Ohanian|Ruffini|1994|pp=469–471}}</ref> Such effects can again be tested through their influence on the orientation of gyroscopes in free fall.<ref>{{Harvnb|Ohanian|Ruffini|1994|loc=sec. 4.7}}, {{Harvnb|Weinberg|1972|loc=sec. 9.7}}; for a more recent review, see {{Harvnb|Schäfer|2004}}</ref> Somewhat controversial tests have been performed using the ] satellites, confirming the relativistic prediction.<ref>{{Harvnb|Ciufolini|Pavlis|2004}}, {{Harvnb|Ciufolini|Pavlis|Peron|2006}}, {{Harvnb|Iorio|2009}}</ref> Also the ] probe around Mars has been used.<ref>{{Harvnb|Iorio|2006}}, {{Harvnb|Iorio|2010}}</ref> | |||

| Finally, there have been various attempts through the years to find modifications to '''general relativity'''. The most famous of these are the ] (also known as scalar-tensor theory), and Rosen's ]. Both of these proposed changes to the field equations, and both have been found to be in conflict with observation. In fact, the viability of any approach that changes the field equations is doubtful due to a proof published in the 1990s that only the Einstein Field Equations can provide both self-consistency and local consistency with special relativity. However, '''general relativity''' is known to be inconsistent with ], a theory which has been better verified than general relativity. So speculation continues that some modification of general relativity is needed. | |||

| == Astrophysical applications == | |||

| ==Quotes== | |||

| === Gravitational lensing === | |||

| {{Main|Gravitational lensing}} | |||

| ]: four images of the same astronomical object, produced by a gravitational lens]] | |||

| The deflection of light by gravity is responsible for a new class of astronomical phenomena. If a massive object is situated between the astronomer and a distant target object with appropriate mass and relative distances, the astronomer will see multiple distorted images of the target. Such effects are known as gravitational lensing.<ref>For overviews of gravitational lensing and its applications, see {{Harvnb|Ehlers|Falco|Schneider|1992}} and {{Harvnb|Wambsganss|1998}}</ref> Depending on the configuration, scale, and mass distribution, there can be two or more images, a bright ring known as an ], or partial rings called arcs.<ref>For a simple derivation, see {{Harvnb|Schutz|2003|loc=ch. 23}}; cf. {{Harvnb|Narayan|Bartelmann|1997|loc=sec. 3}}</ref> | |||

| The ] was discovered in 1979;<ref>{{Harvnb|Walsh|Carswell|Weymann|1979}}</ref> since then, more than a hundred gravitational lenses have been observed.<ref>Images of all the known lenses can be found on the pages of the CASTLES project, {{Harvnb|Kochanek|Falco|Impey|Lehar|2007}}</ref> Even if the multiple images are too close to each other to be resolved, the effect can still be measured, e.g., as an overall brightening of the target object; a number of such "] events" have been observed.<ref>{{Harvnb|Roulet|Mollerach|1997}}</ref> | |||

| Gravitational lensing has developed into a tool of ]. It is used to detect the presence and distribution of ], provide a "natural telescope" for observing distant galaxies, and to obtain an independent estimate of the ]. Statistical evaluations of lensing data provide valuable insight into the structural evolution of ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Narayan|Bartelmann|1997|loc=sec. 3.7}}</ref> | |||

| :''The theory appeared to me then, and still does, the greatest feat of human thinking about nature, the most amazing combination of philosophical penetration, physical intuition, and mathematical skill. But its connections with experience were slender. It appealed to me like a great work of art, to be enjoyed and admired from a distance.'' —] | |||

| === Gravitational-wave astronomy === | |||

| == References == | |||

| {{Main|Gravitational wave|Gravitational-wave astronomy}} | |||

| ]]] | |||