| Revision as of 21:37, 10 August 2007 editElonka (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators70,960 edits Expansion← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:57, 5 December 2024 edit undoIznoRepeat (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users50,076 editsm →Further reading: add WP:TEMPLATECAT to remove from template; genfixesTag: AWB | ||

| (399 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|First capital of Egypt under Muslim rule, in Old Cairo}} | |||

| '''Fustat''' ({{lang-ar|الفسطاط}}), also spelled '''Fostat''', was the first capital city of ] under ] rule. It was built by ] right after the Arab conquest of Egypt in ] CE. The city was eventually absorbed by ], which was built to the north of Fostat during the ] era. Fostat is now part of the 'Old Egypt' District in Cairo. | |||

| {{Infobox settlement | |||

| <!--See the Table at Infobox Settlement for all fields and descriptions of usage--> | |||

| | name = Fustat | |||

| | native_name = الفسطاط | |||

| | settlement_type = Capital of Egypt, 641–750, 905–1168 | |||

| | image_skyline = Fostat-329.jpg | |||

| | imagesize = 250px | |||

| | image_caption = A drawing of Fustat, from Rappoport's ''History of Egypt'' | |||

| | nickname = City of the Tents | |||

| | pushpin_map = Egypt | |||

| | pushpin_label_position = bottom | |||

| | pushpin_mapsize = 250 | |||

| | pushpin_map_caption = Historical location in Egypt | |||

| | pushpin_relief = 1 | |||

| | coordinates = {{Coord|30|00|18|N|31|14|15|E|region:EG-C_type:city|display=inline,title}} | |||

| | subdivision_type = Currently part of | |||

| | subdivision_name = ] | |||

| | subdivision_type1 = ] | |||

| | subdivision_type2 = ] | |||

| | subdivision_type3 = ] | |||

| | subdivision_type4 = ] | |||

| | subdivision_name1 = 641–661 | |||

| | subdivision_name2 = 661–750 | |||

| | subdivision_name3 = 750–969 | |||

| | subdivision_name4 = 969–1168 | |||

| | established_title = Founded | |||

| | established_date = 641 | |||

| | leader_title1 = | |||

| | leader_name1 = | |||

| | unit_pref = Imperial | |||

| | area_total_km2 = | |||

| | area_land_km2 = | |||

| | elevation_footnotes = | |||

| | elevation_m = | |||

| | elevation_ft = | |||

| | population_total = 200,000 | |||

| | population_as_of = 12th century | |||

| | population_blank1_title = Ethnicities | |||

| | population_note = | |||

| | founder = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Fustat''' ({{langx|ar|الفُسطاط|translit=al-Fusṭāṭ}}), also '''Fostat''', was the first ] under ], and the historical centre of modern ]. It was built adjacent to what is now known as ] by the ] Muslim general ] immediately after the Muslim conquest of ] in AD 641, and featured the ], the first ] built in Egypt. | |||

| After ] invasion and conquest of Egypt, ], on the ] coast, became Egypt's capital for hundreds of years. The city was Egypt's first on-Nile capital since the time of the Pharaohs, when Thebes and Memphis had been the capitals. Under Roman rule it was known as Misr, and then its Muslim conquerors renamed it as Fustat in 641. | |||

| The city reached its peak in the 12th century, with a population of approximately 200,000.<ref name="williams-37">Williams, p. 37</ref> It was the centre of administrative power in Egypt, until it was ordered burnt in 1168 by its own ], ], to keep its wealth out of the hands of the invading ]. The remains of the city were eventually absorbed by nearby ], which had been built to the north of Fustat in 969 when the ]s conquered the region and created a new city as a royal enclosure for the Caliph. The area fell into disrepair for hundreds of years and was used as a rubbish dump. | |||

| The city's name comes from the Arabic word ''Fustat'' (فسطاط) which means tent. According to tradition, the location of Fustat was chosen by a bird: A dove laid an egg in the tent on ], the Muslim conqueror of Egypt, just before he was to march on Alexandria. He declared the site of the egg sacred, and when he returned from battle, he told his soldiers to pitch their tents around his, giving his new capital city its name, "Town of the tents", ''Misr al-Fustat''. Egypt's first Islamic mosque was later built on the same site, and the name "Misr" because the Arabic name for Egypt. | |||

| Today, the ruins of Fustat lie within the modern district of ], with few buildings remaining from its days as a capital. Many archaeological digs have revealed the wealth of buried material in the area. Many ancient items recovered from the site are on display in Cairo's ]. | |||

| Fustat remained the beautiful capital and home of the ] and his court, and was considered the center of power in Egypt, but the nearby city of Cairo was growing as well., was nearby Cairo was growing quickly as well. Fustat, however, was renowned for its beauty, with shaded streets, gardens, and markets with houses that were seven stories tall, and could accommodate hundreds of people. The markets were renowned for wonderful wares: iridescent pottery, crystal, and many fruits and flowers available, even during the winter months. | |||

| ==Egyptian capital== | |||

| Eventually Caliph ] decided to move his Court to Cairo, and Fustat's power diminished, but many of its buildings remain visible in Cairo's "Old City." | |||

| Fustat was the ] for approximately 500 years. After the city's founding in 641, its authority was uninterrupted until 750, when the ] dynasty staged a revolt against the ]. This conflict was focused not in Egypt, but elsewhere in the Arab world. When the Abbasids gained power, they moved various capitals to more controllable areas. They had established the centre of their caliphate in ], moving the capital from its previous Umayyad location at ]. Similar moves were made throughout the new dynasty. In Egypt, they moved the capital from Fustat slightly north to the Abbasid city of ], which remained the capital until 868. When the ] took control in 868, the Egyptian capital moved briefly to another nearby northern city, ].<ref name="P44"/> This lasted only until 905, when al-Qatta'i was destroyed and the capital was returned to Fustat. The city again lost its status as capital city when its own vizier, ], ordered its burning in 1168, fearing it might fall into the hands of ], king of the Crusader ]. The capital of Egypt was ultimately moved to ].<ref>{{cite book |title=Cairo |page= |author=AlSayyad, Nezar |publisher=Harvard University Press |year=2011 |isbn=978-0674047860 |url=https://archive.org/details/cairohistoriesof0000alsa/page/75}}</ref> | |||

| == |

==Origin of name== | ||

| According to legend, the location of Fustat was chosen by a bird: A dove laid an egg in the tent of ] (585–664), the ], just before he was to march against ] in 641. His camp at that time was just north of the ] fortress of ].<ref>Yeomans, p. 15</ref><ref name=eyewitness>''Eyewitness'', p. 124</ref> Amr declared the dove's nest as a sign from God, and the tent was left untouched as he and his troops went off to battle. When they returned victorious, Amr told his soldiers to pitch their tents around his, giving his new capital city its name, ''Miṣr al-Fusṭāṭ'', or ''Fusṭāṭ Miṣr'',<ref name="D59">David (2000) p. 59</ref> popularly translated as {{gloss|city of the tents}}, though this is not an exact translation. | |||

| *], ''In an Antique Land'' (Vintage Books, 1994). ISBN 0-679-72783-3 | |||

| *Janet L. Abu-Lughod, ''Cairo: 1001 Years of the City Victorious'' (Princeton University Press, 1971), ISBN 0691030855 | |||

| * {{cite web|url=http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/196905/cairo-a.millennial.htm|title=Cairo, a Millenial|accessdate=2007-08-09|author=Irene Beeson|pages= 24, 26-30 |date=September/October 1969|publisher=]}} | |||

| The word Miṣr was an ancient Semitic root designating Egypt, but in Arabic also has the meaning of a {{gloss|large city, metropolis}} (or, as a verb, {{gloss|to civilize}}), so the name ''Miṣr al-Fusṭāṭ'' could mean {{gloss|metropolis of the tent}}. ''Fusṭāṭ Miṣr'' would mean {{gloss|the pavilion of Egypt}}. (Since it lacks the article on the word ''Miṣr'' it would not be {{gloss|the pavilion of the metropolis}}.) Egyptians to this day call Cairo ''Miṣr'', or, in ], ''Maṣr'', even though this is properly the name of the whole country of Egypt.<ref>{{cite news |title=Notes on the Jews in Fustāt from Cambridge Genizah Documents |author=Worman, Ernest |work=] |date=October 1905 |pages=1–39}}</ref> The country's first mosque, the ], was later built in 642 on the same site of the commander's tent.<ref name="P44"/><ref name="D59"/> | |||

| {{Egypt-geo-stub}} | |||

| ==Early history== | |||

| {{coor title dm|30|00|N|31|14|E|region:EG-C_type:city}} | |||

| ]. Though none of the original structure remains, this mosque was the first one built in Egypt, and it was around this location, at the site of the tent of the commander Amr ibn al-As, that the city of Fustat was built.]] | |||

| For thousands of years, the capital of Egypt was moved with different cultures through multiple locations up and down the Nile, such as ] and ], depending on which dynasty was in power. After ] conquered Egypt around 331 BC, the capital became the city named for him, ], on the ] coast. This situation remained stable for nearly a thousand years. After the army of the Arabian Caliph ] captured the region in the 7th century, shortly after the death of ], he wanted to establish a new capital. When Alexandria fell in September 641, ], the commander of the conquering army, founded a new capital on the eastern bank of the river.<ref name="P44">Petersen (1999) p. 44</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The early population of the city was composed almost entirely of soldiers and their families, and the layout of the city was similar to that of a garrison. Amr intended for Fustat to serve as a base from which to conquer North Africa, as well as to launch further campaigns against Byzantium.<ref name="D59"/> It remained the primary base for Arab expansion in Africa until ] was founded in ] in 670.<ref>Lapidus, p. 41</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Fustat developed as a series of tribal areas, ''khittas'', around the central mosque and administrative buildings.<ref name="P91">Petersen (1999) p. 91</ref> The majority of the settlers came from ], with the next largest grouping from western ], along with some ] and Roman mercenaries. Arabic was generally the primary spoken dialect in Egypt, and was the language of written communication. ] was still spoken in Fustat in the 8th century.<ref>Lapidus, p. 52. "In general, Arabic became the language of written communication in administration, literature, and religion. Arabic also became the primary spoken dialect in the western parts of the Middle East – Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia and Iraq – where languages close to Arabic, such as Aramaic, were already spoken. The spread of Arabic was faster than the diffusion of Islam, but this is not to say that the process was rapid or complete. For example, Coptic was still spoken in Fustat in the 8th century."</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

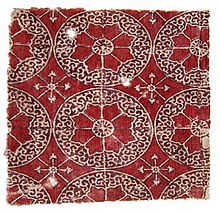

| ] Plate with Bird Motif, 11th century. Archaeological digs have found many kilns and ceramic fragments in Fustat, and it was likely an important production location for Islamic ceramics during the Fatimid period.<ref>{{cite news |title=Petrography of Islamic pottery from Fustat |author1=Mason, Robert B. |author2=Keall, Edward J. |work=Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt |volume=27 |date=1990 |pages=165–184 |jstor=40000079}}</ref>]] | |||

| Fustat was the centre of power in Egypt under the Umayyad dynasty, which had started with the rule of ], and headed the Islamic ] from 660 to 750. However, Egypt was considered only a province of larger powers, and was ruled by governors who were appointed from other Muslim centres such as ], ], and ]. Fustat was a major city, and in the 9th century, it had a population of approximately 120,000.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://i-cias.com/e.o/fustat.htm |title=Fustat |publisher=Encyclopaedia of the Orient |author=Kjeilin, Tore |access-date=2007-08-13 |archive-date=2020-06-29 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200629175726/http://i-cias.com/e.o/fustat.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> But when General ] of the ]n-based ] captured the region, this launched a new era when Egypt was the centre of its own power. Gawhar founded a new city just north of Fustat on August 8, 969, naming it ''Al Qahira'' (]),<ref name=Millennial>{{cite magazine |url=http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/196905/cairo-a.millennial.htm |title=Cairo, a Millennial |access-date=2007-08-09 |author=Beeson, Irene |pages=24, 26–30 |date=September–October 1969 |magazine=] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070930163720/http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/196905/cairo-a.millennial.htm |archive-date=2007-09-30 |url-status=dead}}</ref> and in 971, the Fatimid Caliph ] moved his court from ] in Tunisia to Al Qahira. But Cairo was not intended as a center of government at the time—it was used primarily as the royal enclosure for the Caliph and his court and army, while Fustat remained the capital in terms of economic and administrative power.<ref name="P44"/> The city thrived and grew, and in 987, the geographer Ibn Hawkal wrote that al-Fustat was approximately one third the size of ]. By 1168, it had a population of 200,000. | |||

| The city was known for its prosperity, with shaded streets, gardens, and markets. It contained high-rise residential buildings, some seven storeys tall, which could reportedly accommodate hundreds of people. ] in the 10th century described them as ]s, while ] in the early 11th century described some of them rising up to 14 stories, with roof gardens on the top storey complete with ox-drawn water wheels for irrigation.<ref name="Behrens-Abouseif 1992 6">{{Cite book |title=Islamic Architecture in Cairo |author=Doris Behrens-Abouseif |year=1992 |publisher=] |isbn=90-04-09626-4 |page=6}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |title=Daily Life in Ancient and Modern Cairo |author1=Barghusen, Joan D. |author2=Moulder, Bob |publisher=Twenty-First Century Books |year=2001 |isbn=0-8225-3221-2 |page=11}}</ref> | |||

| The ]n traveller ] wrote of the exotic and beautiful wares in the Fustat markets: iridescent pottery, crystal, and many fruits and flowers, even during the winter months. From 975 to 1075, Fustat was a major production centre for ] and ], and one of the wealthiest cities in the world.<ref name="P91"/><ref>Mason (1995) pp. 5–7</ref> One report stated that it paid taxes that were equivalent to US$150,000 per day, to the administration of Caliph al-Mu'izz. Modern archaeological digs have turned up trade artefacts from as far away as Spain, China, and ]. Excavations have also revealed intricate house and street plans; a basic unit consisted of rooms built around a central courtyard, with an arcade of arches on one side of the courtyard being the principal means of access.<ref name="P91"/> | |||

| ==Destruction and decline== | |||

| ] | |||

| In the mid-12th century, the caliph of Egypt was the teenager ], but his position was primarily ceremonial. The true power in Egypt was that of the vizier, ]. He had been involved in extensive political intrigue for years, working to repel the advances of both the Christian Crusaders, and the forces of the ] from Syria. Shawar managed this by constantly shifting alliances between the two, playing them against each other, and in effect keeping them in a stalemate where neither army could successfully attack Egypt without being blocked by the other.<ref>Maalouf, pp. 159–161</ref> | |||

| However, in 1168, the Christian King ], who had been trying for years to launch a successful attack on Egypt in order to expand the Crusader territories, had finally achieved a certain amount of success. He and his army entered Egypt, sacked the city of ], slaughtered nearly all of its inhabitants, and then continued on towards Fustat. Amalric and his troops camped just south of the city, and then sent a message to the young Egyptian caliph ], only 18 years old, to surrender the city or suffer the same fate as Bilbeis.<ref name=tyerman/> | |||

| Seeing that Amalric's attack was imminent, Shawar ordered Fustat city burned, to keep it out of Amalric's hands.<ref name=weapons/> According to the Egyptian historian ] (1346–1442): | |||

| {{blockquote|text=Shawar ordered that Fustat be evacuated. He forced to leave their money and property behind and flee for their lives with their children. In the panic and chaos of the exodus, the fleeing crowd looked like a massive army of ghosts.... Some took refuge in the mosques and bathhouses...awaiting a Christian onslaught similar to the one in Bilbeis. Shawar sent 20,000 ] pots and 10,000 lighting bombs and distributed them throughout the city. Flames and smoke engulfed the city and rose to the sky in a terrifying scene. The blaze raged for 54 days....<ref name=weapons>{{cite magazine |url=http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/199501/the.oil.weapons.htm |date=January–February 1995 |magazine=] |pages=20–27 |author=Zayn Bilkadi |title=The Oil Weapons |access-date=2007-08-09 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110609223628/http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/199501/the.oil.weapons.htm |archive-date=2011-06-09 |url-status=dead}}</ref>}} | |||

| ]After the destruction of Fustat, the Syrian forces arrived and successfully repelled Amalric's forces. Then with the Christians gone, the Syrians were able to conquer Egypt themselves. The untrustworthy Shawar was put to death, and the reign of the Fatimids was effectively over. The Syrian general Shirkuh was placed in power, but died due to ill health just a few months later, after which his nephew ] became vizier of Egypt on March 2, 1169, launching the ] dynasty.<ref name=tyerman>{{cite book |author=Tyerman, Christopher |author-link=Christopher Tyerman |title=God's War: a new history of the Crusades |publisher=Belknap |pages=–349 |isbn=978-0-674-02387-1 |url=https://archive.org/details/godswarnewhistor00tyer |url-access=registration |year=2006}}</ref> | |||

| With Fustat no more than a dying suburb, the center of government moved permanently to nearby Cairo. Saladin later attempted to unite Cairo and Fustat into one city by enclosing them in massive walls, although this proved to be largely unsuccessful.<ref name="P44"/> | |||

| In 1166 ] went to Egypt and settled in Fustat, where he gained much renown as a physician, practising in the ] and in that of his vizier Ḳaḍi al-Faḍil al-Baisami, and Saladin's successors. The title ''Ra'is al-Umma'' or ''al-Millah'' (Head of the Nation or of the Faith), was bestowed upon him. In Fustat, he wrote his '']'' (1180) and '']''.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Wisdom of Maimonides |author=Hoffman, Edward |pages=163–165 |publisher=Shambhala Productions |year=2008 |location=Boston |isbn=978-1-590-30517-1}}</ref> Some of his writings were later discovered among the manuscript fragments in the '']'' (storeroom) of the ], located in Fustat. | |||

| While the ]s were in power from the 13th century to the 16th century, the area of Fustat was used as a rubbish dump, though it still maintained a population of thousands, with the primary crafts being those of pottery and trash-collecting. The layers of garbage accumulated over hundreds of years, and gradually the population decreased, leaving what had once been a thriving city a wasteland.<ref name=eyewitness/> | |||

| ==Modern Fustat== | |||

| Today, little remains of the grandeur of the old city. The three capitals, Fustat, ] and ] were absorbed into the growing city of Cairo. Some of the old buildings remain visible in the region known as "]", but much of the rest has fallen into disrepair, overgrown with weeds or used as ].<ref name=eyewitness/><ref>{{cite book |title=Song Blue and White Porcelain on the Silk Road |author=Kessler, Adam T. |page=431 |isbn=978-90-04-21859-8 |year=2012 |publisher=Koninklijke Brill |location=Leiden}}</ref> | |||

| The oldest-remaining building from the area is probably the ], from the 9th century, which was built while the capital was in al-Qatta'i. The first mosque ever built in Egypt (and by extension, one of the first mosques built in Africa), the ], is still in use, but has been extensively rebuilt over the centuries, and nothing remains of the original structure.<ref name=eyewitness/> In February 2017 the National Museum of Egyptian Civilisation was inaugurated on a site adjacent to the mosque.<ref>{{cite news |title=9 stunning photos of the newly opened National Museum of Egyptian Civilisation |work=] |date=Feb 21, 2017 |access-date=December 27, 2020 |url=https://www.cairoscene.com/ArtsAndCulture/9-Stunning-Photos-of-the-Newly-Opened-National-Museum-of-Egyptian-Civilisation |archive-date=December 3, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201203073239/https://www.cairoscene.com/ArtsAndCulture/9-Stunning-Photos-of-the-Newly-Opened-National-Museum-of-Egyptian-Civilisation |url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| It is believed that further archaeological digs could yield substantial rewards, considering that the remains of the original city are still preserved under hundreds of years of rubbish.<ref name=eyewitness/> Some archaeological excavations have taken place, the paths of streets are still visible, and some buildings have been partially reconstructed to waist-height. Some artifacts that have been recovered can be seen in Cairo's ].<ref name=gascoigne>{{cite web |url=http://www.egyptvoyager.com/towns_cairo_history_islamic_fustat.htm |title=Islamic Cairo |publisher=egyptvoyager.com |access-date=2007-08-13 |author=Alison Gascoigne |archive-date=2014-12-02 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141202123922/http://www.egyptvoyager.com/towns_cairo_history_islamic_fustat.htm |url-status=live }}</ref>{{Unreliable source?|date=June 2023|reason=A scholarly source should be used for reference on archeological excavations}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{reflist|30em}} | |||

| ==Bibliography== | |||

| *Abu-Lughod, Janet L. ''Cairo: 1001 Years of the City Victorious'' (Princeton University Press, 1971). {{ISBN|0-691-03085-5}}. | |||

| *{{cite magazine |url=http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m3575/is_n1213_v203/ai_20633899 |title=Historic Cairo – rehabilitation of Cairo's historic monuments |date=March 1998 |author=Antoniou, Jim |magazine=]}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=David |first=Rosalie |title=The Experience of Ancient Egypt |year=2000 |isbn=0-415-03263-6 |location=London; New York |publisher=Routledge}} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Eyewitness Travel: Egypt |date=2007 |isbn=978-0-7566-2875-8 |publisher=Dorlin Kindersley Limited, London |url=https://archive.org/details/egypt00dkpu}} | |||

| *Ghosh, Amitav, ''In an Antique Land'' (Vintage Books, 1994). {{ISBN|0-679-72783-3}}. | |||

| *Lapidus, Ira M. (1988). ''A History of Islamic Societies''. Cambridge University Press. {{ISBN|0-521-22552-3}}. | |||

| *Maalouf, Amin (1984). ''The Crusades Through Arab Eyes''. Al Saqi Books. {{ISBN|0-8052-0898-4}}. | |||

| *{{cite journal |last=Mason |first=Robert B. |title=New Looks at Old Pots: Results of Recent Multidisciplinary Studies of Glazed Ceramics from the Islamic World |journal=Muqarnas: Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture |year=1995 |volume=XII |publisher=Brill Academic Publishers |isbn=90-04-10314-7}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Petersen |first=Andrew |title=Dictionary of Islamic Architecture |year=1999 |isbn=0-415-21332-0 |location=London; New York |publisher=Routledge}} | |||

| *{{cite book |author=Yeomans, Richard |title=The Art and Architecture of Islamic Cairo |year=2006 |publisher=Garnet & Ithaca Press |isbn=1-85964-154-7 |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/artarchitectureo0000yeom}} | |||

| *{{cite book |author=Williams, Caroline |title=Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide |year=2002 |publisher=American University in Cairo Press |isbn=977-424-695-0}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| {{commons|Old Cairo#Fustat|Fustat}} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Fustat Finds: Beads, Coins, Medical Instruments, Textiles, and Other Artifacts from the Awad Collection |year=2004 |author=Bacharach, Jere L. |publisher=American University in Cairo Press |isbn=977-424-393-5}} | |||

| *{{cite book |author=Barekeet, Elinoar |title=Fustat on the Nile: The Jewish Elite in Medieval Egypt |year=1999 |publisher=Brill |isbn=90-04-10168-3}} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Al-Fusṭāṭ, its foundation and early urban development |last=Kubiak |first=Wladyslaw |publisher=American University in Cairo Press |location=Cairo, Egypt |year=1987 |isbn=977-424-168-1}} | |||

| *{{cite journal |author=Scanlon, George T. |title=The Pits of Fustat: Problems of Chronology |journal=The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology |volume=60 |pages=60–78 |doi=10.2307/3856171 |publisher=The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 60 |jstor=3856171 |year=1974}} | |||

| *{{cite book |author=Scanlon, George T. |author2=Pinder-Wilson, Ralph |year=2001 |publisher=Altajir World of Islam Trust |isbn=1-901435-07-5 |title=Fustat Glass of the Early Islamic Period: Finds Excavated by the American Research Center in Egypt, 1964–1980}} | |||

| *{{cite journal |author=Stewart, W. A. |title=The Pottery of Fostat, Old Cairo |journal=The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs |volume=39 |issue=220 |date=July 1921 |pages=11–13 + 16–18}} | |||

| *Toler, Pamela D. 2016. Aramco World. Volume 67 (1), pp. 4–9. {{OCLC|895830331}} | |||

| {{Navboxes | |||

| |title = Capital of Egypt | |||

| |list = | |||

| {{s-start}} | |||

| {{succession box|title=]|before=]|after=]|years=641–750}} | |||

| {{succession box|title=]|before=]|after=]|years=905–1169}} | |||

| {{s-end}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Districts of Cairo|cairo}} | |||

| {{Egypt topics}} | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 20:57, 5 December 2024

First capital of Egypt under Muslim rule, in Old Cairo Place in Old Cairo| Fustat الفسطاط | |

|---|---|

| Capital of Egypt, 641–750, 905–1168 | |

A drawing of Fustat, from Rappoport's History of Egypt A drawing of Fustat, from Rappoport's History of Egypt | |

| Nickname: City of the Tents | |

| |

| Coordinates: 30°00′18″N 31°14′15″E / 30.00500°N 31.23750°E / 30.00500; 31.23750 | |

| Currently part of | Old Cairo |

| Rashidun Caliphate | 641–661 |

| Umayyad Caliphate | 661–750 |

| Abbasid Caliphate | 750–969 |

| Fatimid Caliphate | 969–1168 |

| Founded | 641 |

| Founded by | 'Amr ibn al-'As |

| Population | |

| • Total | 200,000 |

Fustat (Arabic: الفُسطاط, romanized: al-Fusṭāṭ), also Fostat, was the first capital of Egypt under Muslim rule, and the historical centre of modern Cairo. It was built adjacent to what is now known as Old Cairo by the Rashidun Muslim general 'Amr ibn al-'As immediately after the Muslim conquest of Egypt in AD 641, and featured the Mosque of Amr, the first mosque built in Egypt.

The city reached its peak in the 12th century, with a population of approximately 200,000. It was the centre of administrative power in Egypt, until it was ordered burnt in 1168 by its own vizier, Shawar, to keep its wealth out of the hands of the invading Crusaders. The remains of the city were eventually absorbed by nearby Cairo, which had been built to the north of Fustat in 969 when the Fatimids conquered the region and created a new city as a royal enclosure for the Caliph. The area fell into disrepair for hundreds of years and was used as a rubbish dump.

Today, the ruins of Fustat lie within the modern district of Old Cairo, with few buildings remaining from its days as a capital. Many archaeological digs have revealed the wealth of buried material in the area. Many ancient items recovered from the site are on display in Cairo's Museum of Islamic Art.

Egyptian capital

Fustat was the capital of Egypt for approximately 500 years. After the city's founding in 641, its authority was uninterrupted until 750, when the Abbasid dynasty staged a revolt against the Umayyads. This conflict was focused not in Egypt, but elsewhere in the Arab world. When the Abbasids gained power, they moved various capitals to more controllable areas. They had established the centre of their caliphate in Baghdad, moving the capital from its previous Umayyad location at Damascus. Similar moves were made throughout the new dynasty. In Egypt, they moved the capital from Fustat slightly north to the Abbasid city of al-Askar, which remained the capital until 868. When the Tulunid dynasty took control in 868, the Egyptian capital moved briefly to another nearby northern city, al-Qatta'i. This lasted only until 905, when al-Qatta'i was destroyed and the capital was returned to Fustat. The city again lost its status as capital city when its own vizier, Shawar, ordered its burning in 1168, fearing it might fall into the hands of Amalric, king of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. The capital of Egypt was ultimately moved to Cairo.

Origin of name

According to legend, the location of Fustat was chosen by a bird: A dove laid an egg in the tent of 'Amr ibn al-'As (585–664), the Muslim conqueror of Egypt, just before he was to march against Alexandria in 641. His camp at that time was just north of the Roman fortress of Babylon. Amr declared the dove's nest as a sign from God, and the tent was left untouched as he and his troops went off to battle. When they returned victorious, Amr told his soldiers to pitch their tents around his, giving his new capital city its name, Miṣr al-Fusṭāṭ, or Fusṭāṭ Miṣr, popularly translated as 'city of the tents', though this is not an exact translation.

The word Miṣr was an ancient Semitic root designating Egypt, but in Arabic also has the meaning of a 'large city, metropolis' (or, as a verb, 'to civilize'), so the name Miṣr al-Fusṭāṭ could mean 'metropolis of the tent'. Fusṭāṭ Miṣr would mean 'the pavilion of Egypt'. (Since it lacks the article on the word Miṣr it would not be 'the pavilion of the metropolis'.) Egyptians to this day call Cairo Miṣr, or, in Egyptian Arabic, Maṣr, even though this is properly the name of the whole country of Egypt. The country's first mosque, the Mosque of Amr, was later built in 642 on the same site of the commander's tent.

Early history

For thousands of years, the capital of Egypt was moved with different cultures through multiple locations up and down the Nile, such as Thebes and Memphis, depending on which dynasty was in power. After Alexander the Great conquered Egypt around 331 BC, the capital became the city named for him, Alexandria, on the Mediterranean coast. This situation remained stable for nearly a thousand years. After the army of the Arabian Caliph Umar captured the region in the 7th century, shortly after the death of Muhammad, he wanted to establish a new capital. When Alexandria fell in September 641, Amr ibn al-As, the commander of the conquering army, founded a new capital on the eastern bank of the river.

The early population of the city was composed almost entirely of soldiers and their families, and the layout of the city was similar to that of a garrison. Amr intended for Fustat to serve as a base from which to conquer North Africa, as well as to launch further campaigns against Byzantium. It remained the primary base for Arab expansion in Africa until Qayrawan was founded in Tunisia in 670.

Fustat developed as a series of tribal areas, khittas, around the central mosque and administrative buildings. The majority of the settlers came from Yemen, with the next largest grouping from western Arabia, along with some Jews and Roman mercenaries. Arabic was generally the primary spoken dialect in Egypt, and was the language of written communication. Coptic was still spoken in Fustat in the 8th century.

Fustat was the centre of power in Egypt under the Umayyad dynasty, which had started with the rule of Muawiyah I, and headed the Islamic caliphate from 660 to 750. However, Egypt was considered only a province of larger powers, and was ruled by governors who were appointed from other Muslim centres such as Damascus, Medina, and Baghdad. Fustat was a major city, and in the 9th century, it had a population of approximately 120,000. But when General Gawhar of the Tunisian-based Fatimids captured the region, this launched a new era when Egypt was the centre of its own power. Gawhar founded a new city just north of Fustat on August 8, 969, naming it Al Qahira (Cairo), and in 971, the Fatimid Caliph al-Mu'izz moved his court from al-Mansuriya in Tunisia to Al Qahira. But Cairo was not intended as a center of government at the time—it was used primarily as the royal enclosure for the Caliph and his court and army, while Fustat remained the capital in terms of economic and administrative power. The city thrived and grew, and in 987, the geographer Ibn Hawkal wrote that al-Fustat was approximately one third the size of Baghdad. By 1168, it had a population of 200,000.

The city was known for its prosperity, with shaded streets, gardens, and markets. It contained high-rise residential buildings, some seven storeys tall, which could reportedly accommodate hundreds of people. Al-Muqaddasi in the 10th century described them as minarets, while Nasir Khusraw in the early 11th century described some of them rising up to 14 stories, with roof gardens on the top storey complete with ox-drawn water wheels for irrigation.

The Persian traveller Nasir-i-Khusron wrote of the exotic and beautiful wares in the Fustat markets: iridescent pottery, crystal, and many fruits and flowers, even during the winter months. From 975 to 1075, Fustat was a major production centre for Islamic art and ceramics, and one of the wealthiest cities in the world. One report stated that it paid taxes that were equivalent to US$150,000 per day, to the administration of Caliph al-Mu'izz. Modern archaeological digs have turned up trade artefacts from as far away as Spain, China, and Vietnam. Excavations have also revealed intricate house and street plans; a basic unit consisted of rooms built around a central courtyard, with an arcade of arches on one side of the courtyard being the principal means of access.

Destruction and decline

In the mid-12th century, the caliph of Egypt was the teenager Athid, but his position was primarily ceremonial. The true power in Egypt was that of the vizier, Shawar. He had been involved in extensive political intrigue for years, working to repel the advances of both the Christian Crusaders, and the forces of the Nur al-Din from Syria. Shawar managed this by constantly shifting alliances between the two, playing them against each other, and in effect keeping them in a stalemate where neither army could successfully attack Egypt without being blocked by the other.

However, in 1168, the Christian King Amalric I of Jerusalem, who had been trying for years to launch a successful attack on Egypt in order to expand the Crusader territories, had finally achieved a certain amount of success. He and his army entered Egypt, sacked the city of Bilbeis, slaughtered nearly all of its inhabitants, and then continued on towards Fustat. Amalric and his troops camped just south of the city, and then sent a message to the young Egyptian caliph Athid, only 18 years old, to surrender the city or suffer the same fate as Bilbeis.

Seeing that Amalric's attack was imminent, Shawar ordered Fustat city burned, to keep it out of Amalric's hands. According to the Egyptian historian al-Maqrizi (1346–1442):

Shawar ordered that Fustat be evacuated. He forced to leave their money and property behind and flee for their lives with their children. In the panic and chaos of the exodus, the fleeing crowd looked like a massive army of ghosts.... Some took refuge in the mosques and bathhouses...awaiting a Christian onslaught similar to the one in Bilbeis. Shawar sent 20,000 naphtha pots and 10,000 lighting bombs and distributed them throughout the city. Flames and smoke engulfed the city and rose to the sky in a terrifying scene. The blaze raged for 54 days....

After the destruction of Fustat, the Syrian forces arrived and successfully repelled Amalric's forces. Then with the Christians gone, the Syrians were able to conquer Egypt themselves. The untrustworthy Shawar was put to death, and the reign of the Fatimids was effectively over. The Syrian general Shirkuh was placed in power, but died due to ill health just a few months later, after which his nephew Saladin became vizier of Egypt on March 2, 1169, launching the Ayyubid dynasty.

With Fustat no more than a dying suburb, the center of government moved permanently to nearby Cairo. Saladin later attempted to unite Cairo and Fustat into one city by enclosing them in massive walls, although this proved to be largely unsuccessful.

In 1166 Maimonides went to Egypt and settled in Fustat, where he gained much renown as a physician, practising in the family of Saladin and in that of his vizier Ḳaḍi al-Faḍil al-Baisami, and Saladin's successors. The title Ra'is al-Umma or al-Millah (Head of the Nation or of the Faith), was bestowed upon him. In Fustat, he wrote his Mishneh Torah (1180) and The Guide for the Perplexed. Some of his writings were later discovered among the manuscript fragments in the geniza (storeroom) of the Ben Ezra Synagogue, located in Fustat.

While the Mamluks were in power from the 13th century to the 16th century, the area of Fustat was used as a rubbish dump, though it still maintained a population of thousands, with the primary crafts being those of pottery and trash-collecting. The layers of garbage accumulated over hundreds of years, and gradually the population decreased, leaving what had once been a thriving city a wasteland.

Modern Fustat

Today, little remains of the grandeur of the old city. The three capitals, Fustat, al-Askar and al-Qatta'i were absorbed into the growing city of Cairo. Some of the old buildings remain visible in the region known as "Old Cairo", but much of the rest has fallen into disrepair, overgrown with weeds or used as garbage dumps.

The oldest-remaining building from the area is probably the Mosque of Ibn Tulun, from the 9th century, which was built while the capital was in al-Qatta'i. The first mosque ever built in Egypt (and by extension, one of the first mosques built in Africa), the Mosque of Amr, is still in use, but has been extensively rebuilt over the centuries, and nothing remains of the original structure. In February 2017 the National Museum of Egyptian Civilisation was inaugurated on a site adjacent to the mosque.

It is believed that further archaeological digs could yield substantial rewards, considering that the remains of the original city are still preserved under hundreds of years of rubbish. Some archaeological excavations have taken place, the paths of streets are still visible, and some buildings have been partially reconstructed to waist-height. Some artifacts that have been recovered can be seen in Cairo's Museum of Islamic Art.

References

- Williams, p. 37

- ^ Petersen (1999) p. 44

- AlSayyad, Nezar (2011). Cairo. Harvard University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0674047860.

- Yeomans, p. 15

- ^ Eyewitness, p. 124

- ^ David (2000) p. 59

- Worman, Ernest (October 1905). "Notes on the Jews in Fustāt from Cambridge Genizah Documents". Jewish Quarterly Review. pp. 1–39.

- Lapidus, p. 41

- ^ Petersen (1999) p. 91

- Lapidus, p. 52. "In general, Arabic became the language of written communication in administration, literature, and religion. Arabic also became the primary spoken dialect in the western parts of the Middle East – Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia and Iraq – where languages close to Arabic, such as Aramaic, were already spoken. The spread of Arabic was faster than the diffusion of Islam, but this is not to say that the process was rapid or complete. For example, Coptic was still spoken in Fustat in the 8th century."

- Mason, Robert B.; Keall, Edward J. (1990). "Petrography of Islamic pottery from Fustat". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. Vol. 27. pp. 165–184. JSTOR 40000079.

- Kjeilin, Tore. "Fustat". Encyclopaedia of the Orient. Archived from the original on 2020-06-29. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- Beeson, Irene (September–October 1969). "Cairo, a Millennial". Saudi Aramco World. pp. 24, 26–30. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- Doris Behrens-Abouseif (1992). Islamic Architecture in Cairo. Brill Publishers. p. 6. ISBN 90-04-09626-4.

- Barghusen, Joan D.; Moulder, Bob (2001). Daily Life in Ancient and Modern Cairo. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 11. ISBN 0-8225-3221-2.

- Mason (1995) pp. 5–7

- Maalouf, pp. 159–161

- ^ Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: a new history of the Crusades. Belknap. pp. 347–349. ISBN 978-0-674-02387-1.

- ^ Zayn Bilkadi (January–February 1995). "The Oil Weapons". Saudi Aramco World. pp. 20–27. Archived from the original on 2011-06-09. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- Hoffman, Edward (2008). The Wisdom of Maimonides. Boston: Shambhala Productions. pp. 163–165. ISBN 978-1-590-30517-1.

- Kessler, Adam T. (2012). Song Blue and White Porcelain on the Silk Road. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. p. 431. ISBN 978-90-04-21859-8.

- "9 stunning photos of the newly opened National Museum of Egyptian Civilisation". Cairo Scene. Feb 21, 2017. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- Alison Gascoigne. "Islamic Cairo". egyptvoyager.com. Archived from the original on 2014-12-02. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

Bibliography

- Abu-Lughod, Janet L. Cairo: 1001 Years of the City Victorious (Princeton University Press, 1971). ISBN 0-691-03085-5.

- Antoniou, Jim (March 1998). "Historic Cairo – rehabilitation of Cairo's historic monuments". Architectural Review.

- David, Rosalie (2000). The Experience of Ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-03263-6.

- Eyewitness Travel: Egypt. Dorlin Kindersley Limited, London. 2007. ISBN 978-0-7566-2875-8.

- Ghosh, Amitav, In an Antique Land (Vintage Books, 1994). ISBN 0-679-72783-3.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (1988). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22552-3.

- Maalouf, Amin (1984). The Crusades Through Arab Eyes. Al Saqi Books. ISBN 0-8052-0898-4.

- Mason, Robert B. (1995). "New Looks at Old Pots: Results of Recent Multidisciplinary Studies of Glazed Ceramics from the Islamic World". Muqarnas: Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. XII. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-10314-7.

- Petersen, Andrew (1999). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21332-0.

- Yeomans, Richard (2006). The Art and Architecture of Islamic Cairo. Garnet & Ithaca Press. ISBN 1-85964-154-7.

- Williams, Caroline (2002). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 977-424-695-0.

Further reading

- Bacharach, Jere L. (2004). Fustat Finds: Beads, Coins, Medical Instruments, Textiles, and Other Artifacts from the Awad Collection. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 977-424-393-5.

- Barekeet, Elinoar (1999). Fustat on the Nile: The Jewish Elite in Medieval Egypt. Brill. ISBN 90-04-10168-3.

- Kubiak, Wladyslaw (1987). Al-Fusṭāṭ, its foundation and early urban development. Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 977-424-168-1.

- Scanlon, George T. (1974). "The Pits of Fustat: Problems of Chronology". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 60. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 60: 60–78. doi:10.2307/3856171. JSTOR 3856171.

- Scanlon, George T.; Pinder-Wilson, Ralph (2001). Fustat Glass of the Early Islamic Period: Finds Excavated by the American Research Center in Egypt, 1964–1980. Altajir World of Islam Trust. ISBN 1-901435-07-5.

- Stewart, W. A. (July 1921). "The Pottery of Fostat, Old Cairo". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 39 (220): 11–13 + 16–18.

- Toler, Pamela D. 2016. "In Fragments from Fustat, Glimpses of a Cosmopolitan Old Cairo." Aramco World. Volume 67 (1), pp. 4–9. OCLC 895830331

| Capital of Egypt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Districts and suburbs of Greater Cairo | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cairo Governorate |

|   | ||||||||

| Giza Governorate |

| |||||||||

| Qalyubia Governorate |

| |||||||||

Categories: