| Revision as of 04:25, 9 September 2007 editDRTllbrg (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users3,435 editsm Reverted 1 edit by Pailman identified as vandalism to last revision by Dobi. w/TW← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 01:08, 31 December 2024 edit undoWindTempos (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers9,715 editsm Rollback edit(s) by 80.5.48.68 (talk): Vandalism (RW 16.1)Tags: RW Rollback | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Carcinogenic fibrous silicate mineral}} | |||

| {{Otheruses}} | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2020}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{infobox mineral | |||

| ] | |||

| | name = Asbestos | |||

| ]. The ruler is 1 cm. | |||

| | image = Asbestos with muscovite.png | |||

| ]]] | |||

| | imagesize = 260px | |||

| | alt = | |||

| | caption = Fibrous ] asbestos on ] | |||

| | category = ] | |||

| | formula = | |||

| | strunz = 09.ED.15 | |||

| | dana = 71.01.02d.03 | |||

| | symmetry = | |||

| | unit cell = | |||

| | molweight = 277.11 g | |||

| | color = Green, red, yellow, white, gray, blue | |||

| | habit = Amorphous, granular, massive | |||

| | system = ], ] | |||

| | twinning = | |||

| | cleavage = ] | |||

| | fracture = Fibrous | |||

| | tenacity = | |||

| | mohs = 2.5.6.0 | |||

| | luster = Silky | |||

| | streak = White | |||

| | diaphaneity = | |||

| | gravity =2.4–3.3 | |||

| | density = | |||

| | polish = | |||

| | opticalprop = Biaxial | |||

| | refractive =1.53–1.72 | |||

| | birefringence = 0.008 | |||

| | pleochroism = | |||

| | 2V = 20° to 60° | |||

| | dispersion = Relatively weak | |||

| | extinction =Parallel or oblique | |||

| | length fast/slow = | |||

| | fluorescence = Non-fluorescent | |||

| | absorption = | |||

| | melt ={{convert|400 to 1040|C}} | |||

| | fusibility = | |||

| | diagnostic = | |||

| | solubility = | |||

| | impurities = | |||

| | alteration = | |||

| | other = | |||

| | prop1 = | |||

| | prop1text = | |||

| | references = | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Asbestos''' ({{IPAc-en|æ|s|ˈ|b|ɛ|s|t|ə|s|,_|æ|z|-|,_|-|t|ɒ|s}} {{respell|ass|BES|təs|,_|az|-|,_|-|toss}})<ref>{{cite Dictionary.com|asbestos}}</ref> is a group of naturally occurring, ], ]ic and fibrous ]s. There are six types, all of which are composed of long and thin fibrous ], each fibre (] with length substantially greater than width)<ref>{{cite book |chapter-url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK20329/ |title=Exposure and Disposition – Asbestos – NCBI Bookshelf |chapter=Exposure and Disposition |chapter-format= |year=2006 |publisher=National Academies Press (US) |accessdate=}}</ref> being composed of many microscopic "fibrils" that can be released into the atmosphere by ] and other processes. Inhalation of asbestos fibres can lead to various dangerous ] conditions, including ], ], and ]. As a result of these health effects, asbestos is considered a serious ] and ].<ref name=blf/> | |||

| The word '''Asbestos''' is derived from a ] adjective meaning inextinguishable. Asbestos is a naturally occurring mineral. It is distinguished from other minerals by the fact that its crystals form long, thin fibers. Deposits of asbestos are found throughout the world. The primary sites of commercial production are: the ], ], ], ], and ]. ] is also indicated in its production. | |||

| Archaeological studies have found evidence of asbestos being used as far back as the ] to strengthen ] pots,<ref>{{cite book|author1=Yildirim Dilek|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eYHEEWhye94C&pg=PA449|title=Ophiolite Concept and the Evolution of Geological Thought|author2=Sally Newcomb|publisher=Geological Society of America|year=2003|isbn=978-0-8137-2373-0|page=449}}</ref> but large-scale mining began at the end of the 19th century when manufacturers and builders began using asbestos for its desirable physical properties. Asbestos is an excellent ] and ], and is highly fire resistant, so for much of the 20th century, it was very commonly used around the world as a building material (particularly for its fire-retardant properties), until ] were more widely recognized and acknowledged in the 1970s.<ref>Bureau of Naval Personnel, ''Basic Electricity''. 1969: US Navy.</ref><ref>{{cite web|last=Kazan-Allen|first=Laurie|date=15 July 2019|title=Chronology of Asbestos Bans and Restrictions|url=http://www.ibasecretariat.org/chron_ban_list.php|publisher=International Ban Asbestos Secretariat}}</ref> Many buildings constructed before the 1980s contain asbestos.<ref name=kazan>{{cite web|last=Kazan-Allen|first=Laurie|date=2 May 2002|title=Asbestos: Properties, Uses and Problems|url=http://ibasecretariat.org/lka_prop.php|publisher=International Ban Asbestos Secretariat}}</ref> | |||

| The Greeks termed asbestos the "miracle mineral" as they admired it for its soft and pliant properties, as well as its ability to withstand heat. Asbestos was spun and woven into cloth in the same manner as cotton. It was also utilized for wicks in sacred lamps. Romans likewise recognized the properties of asbestos and it is thought that they cleaned asbestos tablecloths by throwing them into the flames of fire. | |||

| The use of asbestos for construction and ] has been made illegal in many countries.<ref name=blf>{{cite web |url=https://www.blf.org.uk/support-for-you/asbestos-related-conditions/what-is-asbestos |publisher=British Lung Foundation |title=What is asbestos? |date=28 September 2015 |access-date=26 May 2019 |archive-date=16 April 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200416095014/https://www.blf.org.uk/support-for-you/asbestos-related-conditions/what-is-asbestos |url-status=dead }}</ref> Despite this, around 255,000 people are thought to die each year from diseases related to asbestos exposure.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Furuya |first1=Sugio |last2=Chimed-Ochir |first2=Odgerel |last3=Takahashi |first3=Ken |last4=David |first4=Annette |last5=Takala |first5=Jukka |title=Global Asbestos Disaster |journal=International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health |date=May 2018 |volume=15 |issue=5 |pages=1000 |doi=10.3390/ijerph15051000 |doi-access=free |pmid=29772681 |pmc=5982039 |issn=1661-7827}}</ref> In part, this is because many older buildings still contain asbestos; in addition, the consequences of exposure can take decades to arise. The latency period (from exposure until the diagnosis of negative health effects) is typically 20 years.<ref name=kazan/><ref name="chemistryworld.com">{{cite web|last=King|first=Anthony|date=25 June 2017|title=Asbestos, explained|url=https://www.chemistryworld.com/news/why-asbestos-is-still-used-around-the-world/3007504.article|publisher=Royal Society of Chemistry}}</ref> The most common diseases associated with chronic asbestos exposure are ] (scarring of the lungs due to asbestos inhalation) and ] (a type of cancer).<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| Asbestos became increasingly popular to manufacturers and builders in the late 1800s due to its heat resistance, electrical resistance, sound absorbing, tensile strength and chemical resistant properties. | |||

| Many developing countries still support the use of asbestos as a ], and mining of asbestos is ongoing, with the top producer, ], having an estimated production of 790,000 tonnes in 2020.<ref>{{Cite book|chapter-url=https://doi.org/10.3133/mcs2021|chapter=Mineral Commodity Summaries 2021|first1=Daniel M. |last1=Flanagan|title=Mineral Commodity Summaries|publisher=U.S. Geological Survey|date=29 January 2021|pages=26–27|doi=10.3133/mcs2021|s2cid=242973747}}</ref> | |||

| When asbestos is used for its resistance to fire or heat, the fibers are often mixed with ] or woven into fabric or mats. Asbestos is used in ] shoes and ]s for its heat resistance, and in the past was used on electric oven and hotplate wiring for its ] at elevated temperature, and in buildings for its ] and insulating properties, ], flexibility, and resistance to chemicals. The ] of ] can cause a number of serious illnesses, including ] and ]. Since the mid 1980s, many uses of asbestos are banned in multiple countries. | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| ==Types of asbestos and associated fibres== | |||

| The word "asbestos", first used in the 1600s, ultimately derives from the {{langx|grc|ἄσβεστος}}, meaning "unquenchable" or "inextinguishable".<ref name=Alleman&Mossman1997>{{Cite journal|date=July 1997 |author=Alleman, James E. |author2=Mossman, Brooke T|author2-link= Brooke T. Mossman |title=Asbestos Revisited |journal=] |pages=54–57 |url=http://virlab.virginia.edu/Nanoscience_class/lecture_notes/Lecture_14_Materials/Asbestos_CNT/Sci%20Am%20-%20Asbestos%20Revisited%20-%20July%201997.pdf |access-date=26 November 2010 |bibcode=1997SciAm.277a..70A |volume=277 |issue=1 |doi=10.1038/scientificamerican0797-70 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100603095555/http://www.virlab.virginia.edu/Nanoscience_class/lecture_notes/Lecture_14_Materials/Asbestos_CNT/Sci%20Am%20-%20Asbestos%20Revisited%20-%20July%201997.pdf |archive-date=3 June 2010 }}</ref><ref name=Bostock&Riley1856>{{Cite book |year=1856 |author=Bostock, John |translator=] |chapter=Asbestinon |page=137 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/stream/naturalhistoryof04plinrich#page/137/mode/1up/search/asbestinon |title=The Natural History of Pliny|volume=IV |place=London |publisher=Henry G. Bohn |url=https://archive.org/stream/naturalhistoryof04plinrich#page/n3/mode/2up |access-date=26 November 2010|author-link=John Bostock (physician) }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Shorter Oxford English Dictionary|url=https://archive.org/details/shorteroxfordeng00will_0|url-access=registration|publisher=Oxford University Press|edition= 5th|year=2002|isbn=978-0-19-860457-0 }}</ref><ref>{{LSJ|a)/sbestos|ἄσβεστος|ref}}.</ref> The name reflects use of the substance for ]s that would never burn up.<ref name=Alleman&Mossman1997/> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| It was adopted into English via the ] ''abestos'', which got the word from Greek via ], but in the original Greek, "asbestos" actually referred to ]. It is said by the ] that the word was wrongly used by ] for what we now call asbestos, and that he popularized the ]. Asbestos was originally referred to in Greek as ''amiantos'', meaning "undefiled",<ref>{{LSJ|a)mi/antos|ἀμίαντος|shortref}}.</ref> because when thrown into a ] it came out unmarked. "Amiantos" is the source for the word for asbestos in many languages, such as the ] ''amianto'' and the ] ''amiante''. It had also been called "amiant" in English in the early 15th century, but this usage was superseded by "asbestos".<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.etymonline.com/word/asbestos|title=asbestos {{!}} Origin and meaning of asbestos by Online Etymology Dictionary|website=www.etymonline.com|language=en|access-date=2018-12-14}}</ref> The word is pronounced {{IPAc-en|æ|s|ˈ|b|ɛ|s|t|ə|s}} or {{IPAc-en|æ|s|ˈ|b|ɛ|s|t|ɒ|s}}.<ref>{{cite web |title=asbestos |url=https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/asbestos |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190321081058/https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/asbestos |archive-date=21 March 2019 |website=Oxford Living Dictionaries |publisher=Oxford University Press |access-date=21 March 2019}}</ref> | |||

| Six minerals are defined as "asbestos" including: ], ], ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| ===White asbestos=== | |||

| ], ] 12001-29-5, is obtained from ] rocks which is common throughout the world. The rocks are called serpentine because their fibers curl; chrysotile fibers are curly as opposed to fibers from amosite, crocidolite, tremolite, actinolite, and anthophyllite which are needlelike.<ref></ref> Chrysotile, along with other types of asbestos, has been banned in dozens of countries and is only allowed in the ] and ] in very limited circumstances. Chrysotile is used more than any other type and accounts for about 95% of the asbestos found in buildings in America.<ref name="wdnr"></ref> Applications where Chrysotile might be used include the use of ]. It is more flexible than amphibole types of asbestos; it can be spun and woven into ]. Chrysotile, like all other forms of industrial asbestos, has produced tumors in animals. ]s have been observed in people who were occupationally exposed to chrysotile, family members of the occupationally exposed, and residents who lived close to asbestos factories and mines.<ref></ref> | |||

| == |

== History == | ||

| {{More citations needed section|date=May 2016}} | |||

| ], CAS No. 12172-73-5, is a ] for the ]s belonging to the '']'' - ''Grunerite'' ] series, commonly from ], named as an ] from Asbestos Mines of South Africa. One formula given for amosite is ]<sub>7</sub>Si<sub>8</sub>O<sub>22</sub>(OH)<sub>2</sub>. It is found most frequently as a fire retardant in thermal insulation products and ceiling tiles.<ref name="wdnr"/> This type of asbestos, like all asbestos, is very hazardous. | |||

| Asbestos has been used for thousands of years to create flexible objects that resist fire, including napkins, but, in the modern era, companies began producing consumer goods containing asbestos on an industrial scale.<ref name="Education1979">{{cite book | date = 1979 | title = Oversight Hearings on Asbestos Health Hazards to Schoolchildren: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Elementary, Secondary, and Vocational Education of the Committee on Education and Labor, House of Representatives, Ninety-sixth Congress, First Session, on H.R. 1435 and H.R. 1524 | publisher = U.S. Government Printing Office | page = 485 | oclc = 1060686493 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=aVrRAAAAMAAJ}}</ref> Today, the risk of asbestos has been recognized; the use of asbestos is completely banned in 66 countries and strictly regulated in many others.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Kazan-Allen |first1=Laurie |title=Current Asbestos Bans |url=http://ibasecretariat.org/alpha_ban_list.php |website=International Ban Asbestos Secretariat |access-date=10 August 2022}}</ref><ref name="TaylorCullinanBlanc2016">{{cite book | author1 = Anthony Newman Taylor | author2 = Paul Cullinan | author3 = Paul Blanc | author4 = Anthony Pickering | date = 25 November 2016 | title = Parkes' Occupational Lung Disorders | publisher = CRC Press | page = 157 | isbn = 978-1-4822-4142-6 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=Us9BDgAAQBAJ|access-date=10 August 2022}}</ref> | |||

| === |

===Early references and uses=== | ||

| {{For|Chinese "fire-laundered cloth" in antiquity and medieval accounts|huoshu}} | |||

| ], CAS No. 12001-28-4 is an amphibole from Africa and ]. It is the fibrous form of the amphibole riebeckite. Blue asbestos is commonly thought of as the most dangerous type of asbestos (see above and below). One formula given for crocidolite is ]<sub>2</sub>Fe<sup>2+</sup><sub>3</sub>Fe<sup>3+</sup><sub>2</sub>Si<sub>8</sub>O<sub>22</sub>(OH)<sub>2</sub>. This type of asbestos is very hazardous. | |||

| Asbestos use dates back at least 4,500 years, when the inhabitants of the Lake ] region in East ] strengthened earthenware pots and cooking utensils with the asbestos mineral ]; archaeologists call this style of pottery "]".<ref name="Ross&Nolan2003">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eYHEEWhye94C|title=Ophiolite Concept and the Evolution of Geological Thought|author=Ross, Malcolm|author2=Nolan, Robert P|publisher=]|year=2003|isbn=978-0-8137-2373-0|editor=Dilek, Yildirim|series=Special Paper 373|place=Boulder, Colorado|chapter=History of asbestos discovery and use and asbestos-related disease in context with the occurrence of asbestos within the ophiolite complexes|editor2=Newcomb, Sally|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eYHEEWhye94C&pg=PA447|name-list-style=amp}}</ref> Some archaeologists believe that ancient peoples{{clarify|date=March 2024}} made shrouds of asbestos, wherein they burned the bodies of their kings to preserve only their ashes and to prevent the ashes being mixed with those of wood or other combustible materials commonly used in ].<ref name="histsci">{{cite book|url=https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/A4C5AV6Q7LZ5DY8E/full/A5PMBHDE7IMK3S86|title=Cyclopædia|last=Chambers|first=Ephraim|date=1728|access-date=3 March 2024|page=147}}</ref><ref>Pliny the Elder. In ''The Natural History''</ref> Others assert that these peoples used asbestos to make perpetual wicks for ] or other lamps.<ref name="Ucalgary" /> A famous example is the golden lamp ''asbestos lychnis'', which the sculptor ] made for the ].<ref>{{cite book|title=Acropolis museum guide|last1=Eleftheratou|first1=S.|date=2016|publisher=Acropolis Museum Editions|page=258}}</ref> In more recent centuries, asbestos was indeed used for this purpose. | |||

| A once-purported first description of asbestos occurs in ], ''On Stones'', from around 300 BC, but this identification has been refuted.<ref>{{cite book|last=Needham |first=Joseph |author-link=Joseph Needham |chapter=Asbestos |title=Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth |publisher=Cambridge University Press |date=1959 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jfQ9E0u4pLAC&pg=RA1-PA656 |pages=656<!--655ff–--> |isbn=<!--0521058015, -->9780521058018}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|chapter-url=http://www.farlang.com/gemstones/theophrastus-on-stones/page_088|title=Theophrastus on Stones: Introduction, Greek Text, English Translation, and Commentary|last1=Caley |first1=Earl R. |last2=Richards |first2=John F. C. |series=Graduate School Monographs: Contributions in Physical Science, No. 1 |publisher=The Ohio State University |year=1956 |location=Columbus, OH |pages=87–88|chapter=Commentary|quote=Moore thought that Theophrastus was really referring to asbestos. The colour of the stone makes this unlikely, though its structure makes it less improbable since some forms of decayed wood do have a fibrous structure like asbestos ... It is, however, unlikely that Theophrastus is alluding to asbestos since the mineral does not occur in the locality mentioned ... It is much more probable that Theophrastus is referring to the well-known brown fibrous ].|access-date=31 January 2013|archive-date=24 December 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131224114624/http://www.farlang.com/gemstones/theophrastus-on-stones/page_088}}</ref> In both modern and ancient ], the usual name for the material known in English as "asbestos" is ''amiantos'' ("undefiled", "pure"), which was adapted into the French as ''amiante'' and into Italian, Spanish and Portuguese as ''amianto''. In ], the word ἀσβεστος or ασβέστης stands consistently and solely for ]. | |||

| Notes: chrysotile commonly occurs as soft friable ]. Asbestiform amphibole may also occur as soft friable fibers but some varieties such as amosite are commonly straighter. All forms of asbestos are fibrillar in that they are composed of fibers with widths less than 1 ] that occur in bundles and have very long lengths. Asbestos with particularly fine fibers is also referred to as "amianthus". | |||

| Amphiboles such as tremolite have a sheetlike ] ]. Serpentine (chrysotile) has a stringlike crystalline structure.<ref>{{cite book|author=Edward De Barry Barnett|title=Inorganic Chemistry|edition=2nd Edition|publisher=Longmans|year=1959|id= }}</ref> Tremolite often comtaminates chrysotile asbestos, thus creating an additional hazard. | |||

| The term ''asbestos'' is traceable to Roman naturalist ]'s first-century manuscript '']'' and his use of the term ''asbestinon'', meaning "unquenchable"; he described the mineral as being more expensive than ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20240207-asbestos-the-strange-past-of-the-magic-mineral|title=Asbestos: The strange past of the 'magic mineral'|work=]|date = February 7, 2024}}</ref><ref name="Alleman&Mossman1997" /><ref name="Bostock&Riley1856" /><ref name="Ross&Nolan2003" /> While Pliny or his nephew ] is popularly credited with recognising the detrimental effects of asbestos on human beings,<ref name="Env_Chem">{{cite web|url=http://environmentalchemistry.com/yogi/environmental/asbestoshistory2004.html|title=History of Asbestos|last=Barbalace|first=Roberta C.|date=22 October 1995|publisher=Environmentalchemistry.com|access-date=12 January 2010}}</ref> examination of the primary sources reveals no support for either claim.<ref name="Maines2005">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5r2jEGLvxP4C|title=Asbestos and Fire: Technological Trade-offs and the Body at Risk|last=Maines|first=Rachel|publisher=]|year=2005|isbn=978-0-8135-3575-3|page=7}}</ref> | |||

| ===Other asbestos=== | |||

| Other regulated asbestos minerals, such as tremolite asbestos, CAS No. 77536-68-6, ]<sub>2</sub>Mg<sub>5</sub>Si<sub>8</sub>O<sub>22</sub>(OH)<sub>2</sub>; actinolite asbestos (or ''smaragdite''), CAS No. 77536-66-4, Ca<sub>2</sub>(Mg, Fe)<sub>5</sub>(Si<sub>8</sub>O<sub>22</sub>)(OH)<sub>2</sub>; and anthophyllite asbestos, CAS No. 77536-67-5, (Mg, Fe)<sub>7</sub>Si<sub>8</sub>O<sub>22</sub>(OH)<sub>2</sub>; are less commonly used industrially but can still be found in a variety of construction materials and insulation materials and have been reported in the past to occur in a few ]. | |||

| In China, accounts of obtaining ''huo huan bu'' ({{lang|zh|火浣布}}) or "fire-laundered cloth" certainly dates to the Wei dynasty, and there are claims they were known as early as in the ], though not substantiated except in writings thought to date much later <ref name="cheng1991">{{cite book|last=Cheng |first=Weiji |author-link=<!--Weiji Cheng--> |title=History of Textile Technology of Ancient China |publisher=Science Press New York |date=1992 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nM0fAQAAIAAJ&q=%22huo+huan%22 |page=451|isbn=<!--7030005481,-->9787030005489}}</ref>{{sfnp|Needham|1959|pp=656–657}} (see '']'' or "fire rat"). | |||

| Other natural and not currently regulated asbestiform minerals, such as richterite, Na(CaNa)(Mg,Fe<sup>++</sup>)<sub>5</sub>(Si<sub>8</sub>O<sub>22</sub>)(OH)<sub>2</sub>, and winchite, (CaNa)Mg<sub>4</sub>(Al,Fe<sup>3+</sup>)(Si<sub>8</sub>O<sub>22</sub>)(OH)<sub>2</sub>, may be found as a contaminant in products such as the ] containing ] insulation manufactured by ]. These minerals are thought to be no less harmful than tremolite, amosite, or crocidolite, but since they are not regulated, they are referred to as "asbestiform" rather than asbestos although may still be related to diseases and hazardous. | |||

| ], a Christian bishop living in 4th-century Egypt, references asbestos in one of his writings. Around the year 318, he wrote as follows: | |||

| In 1989 the ] (EPA) issued the Asbestos Ban and Phase Out Rule which was subsequently overturned in the case of Corrosion Proof Fittings v. ] Environmental Protection Agency, 1991. This ruling leaves many consumer products that can still legally contain trace amounts of asbestos. For a clarification of products which legally contain asbestos visit the EPA's clarification statement.<ref> (PDF format)</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote|The natural property of fire is to burn. Suppose, then, that there was a substance such as the Indian asbestos is said to be, which had no fear of being burnt, but rather displayed the impotence of the fire by proving itself unburnable. If anyone doubted the truth of this, all he need do would be to wrap himself up in the substance in question and then touch the fire."<ref>{{cite book |author=Athanasius |title=On the Incarnation |year=2018 |publisher=GLH Publishing |isbn=978-1-948648-24-0 |page=49}}</ref>}} | |||

| Wealthy ] amazed guests by cleaning a cloth by exposing it to ]. For example, according to ], one of the curious items belonging to ] Parviz, the great ] king (r. 590–628), was a napkin ({{langx|fa|منديل}}) that he cleaned simply by throwing it into fire. Such cloth is believed to have been made of asbestos imported over the ].<ref>New Encyclopædia Britannica (2003), vol. 6, p. 843</ref> According to ] in his book ''Gems'', any cloths made of asbestos ({{langx|fa|آذرشست}}, ''āzarshost'') were called ''shostakeh'' ({{langx|fa|شستكه}}).<ref>]</ref> Some Persians believed the fiber was the fur of an animal called the '']'' ({{langx|fa|سمندر}}), which lived in fire and died when exposed to water;<ref name="Ucalgary">{{cite web|url=http://www.iras.ucalgary.ca/~volk/sylvia/Asbestos.htm|title=University of Calgary|date=30 September 2001|publisher=Iras.ucalgary.ca|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091105005311/http://www.iras.ucalgary.ca/~volk/sylvia/Asbestos.htm|archive-date=5 November 2009|access-date=12 January 2010}}</ref><ref> EnvironmentalChemistry.com website</ref> this was where the former belief originated that the ] could tolerate fire.<ref>{{Cite magazine|url=https://www.wired.com/2014/08/fantastically-wrong-homicidal-salamander/|title=Fantastically Wrong: The Legend of the Homicidal Fire-Proof Salamander|magazine=WIRED|language=en-US|access-date=2016-05-03}}</ref> ], the first ] (800–814), is also said to have possessed such a tablecloth.<ref name="TIME1926">{{Cite magazine|date=29 November 1926|title=Science: Asbestos|url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,729732,00.html|magazine=]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110131223759/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0%2C9171%2C729732%2C00.html|archive-date=31 January 2011|access-date=11 January 2011}}</ref> | |||

| ==Production trends== | |||

| ] | |||

| In 2005, the world mined 2,200,000 tons of asbestos, Russia was the largest producer with about 40% world share followed by China and Kazakhstan, reports the ].<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | last = | |||

| | first = | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | coauthors = | |||

| | title =World Mineral Production 2001-2005 | |||

| | work = | |||

| | publisher =British Geological Survey | |||

| | date = | |||

| | url =http://www.mineralsuk.com/britmin/wmp_2001_2005.pdf | |||

| | pages = | |||

| | format = | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | accessdate = 2007-08-03 }}</ref> | |||

| ] recounts having been shown, in a place he calls ''Ghinghin talas'', "a good vein from which the cloth which we call of salamander, which cannot be burnt if it is thrown into the fire, is made ..."<ref name="PoloMoule1938">{{cite book|url=https://archive.org/stream/descriptionofwor01polo#page/156/mode/2up/search/salamander|title=Marco Polo: the Description of the World: A.C. Moule & Paul Pelliot|last1=Polo|first1=Marco|author2=A C. Moule|author3=Paul Pelliot|publisher=G. Routledge & Sons|year=1938|pages=156–57|access-date=31 January 2013}}</ref> | |||

| ==Uses== | |||

| ===Historic usage=== | |||

| Asbestos was named by the ancient Greeks who also recognized certain hazards of the material. The Greek geographer ] and the Roman naturalist ] noted that the material damaged lungs of slaves who wove it into cloth.<ref name="resource_center"></ref> ], the first Holy Roman Emperor, had a tablecloth made of asbestos.<ref name="MC"></ref><ref name="MARC"> Mesothelioma Applied Research Center</ref> Wealthy Persians, who bought asbestos imported over the ], amazed guests by cleaning the cloth simply by exposing it to fire. The Persians believed the fiber was fur from an animal that lived in fire and died when exposed to water.<ref name="Ucalgary"></ref><ref> EnvironmentalChemistry.com website</ref> Some archeologists believe that ancients made shrouds of asbestos, wherein they burned the bodies of their kings, in order to preserve only their ashes, and prevent their being mixed with those of wood or other combustible materials commonly used in funeral pyres.<ref name=histsci> This article incorporates content from the 1728 Cyclopaedia, a publication in the public domain.</ref> | |||

| ===Industrial era=== | |||

| Others assert that the ancients used asbestos to make perpetual wicks for ] or other lamps.<ref name="MARC"/><ref name="Ucalgary"/> In more recent centuries, asbestos was indeed used for this purpose. Although asbestos causes skin to itch upon contact, ] indicates that it was prescribed for diseases of the skin, and particularly for the itch. It is possible that they used the term ''asbestos'' for ], because the two terms have often been confused throughout history.<ref name=histsci/> | |||

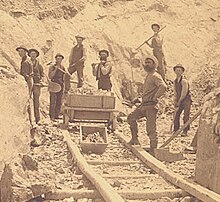

| ], ]. By 1895, mining was increasingly mechanized.]] | |||

| The large-scale asbestos industry began in the mid-19th century. Early attempts at producing asbestos paper and cloth in Italy began in the 1850s but were unsuccessful in creating a market for such products. Canadian samples of asbestos were displayed in London in 1862, and the first companies were formed in England and Scotland to exploit this resource. Asbestos was first used in the manufacture of yarn, and German industrialist Louis Wertheim adopted this process in his factories in Germany. | |||

| <ref name="Selikoff">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ARKaW4uP9BgC|title=Asbestos and Disease|author=Selikoff, Irving J.|publisher=Elsevier|year=1978|isbn=978-0-323-14007-2|pages=8–20}}</ref> In 1871, the Patent Asbestos Manufacturing Company was established in ], and during the following decades, the ] area became a centre for the nascent industry.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.clydebankasbestos.org/index.php?page=asbestos-clydebank|title=Asbestos & Clydebank|publisher=Clydebank Asbestos Group|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140606230508/http://www.clydebankasbestos.org/index.php?page=asbestos-clydebank|archive-date=6 June 2014}}</ref> | |||

| ], ], June 1944]] | |||

| Asbestos became more widespread during the industrial revolution, in the 1860's it was used as insulation in the US and Canada. ] of the first commercial asbestos mine began in 1879 in the ] foothills of ].<ref name=hamptonroads></ref> By the mid 20th century uses included fire retardant coatings, concrete, bricks, pipes and fireplace cement, heat, fire, and acid resistant gaskets, pipe insulation, ceiling insulation, fireproof drywall, flooring, roofing, lawn furniture, and drywall joint compound.<ref name="MARC"/> | |||

| Industrial-scale mining began in the ], ], from the 1870s. Sir ] was the first to notice the large deposits of ] in the hills in his capacity as head of ]. Samples of the minerals from there were displayed in London and elicited much interest.<ref name="Selikoff" /> With the opening of the ] in 1876, mining entrepreneurs such as ] established the asbestos industry in the province.<ref name="wood"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303173753/http://www.ourroots.ca/e/toc.aspx?id=11253 |date=3 March 2016 }} Wood, WCH; Atherton, WH; Conklin, EP pp. 814–5</ref> The 50-ton output of the mines in 1878 rose to over 10,000 tonnes in the 1890s with the adoption of machine technologies and expanded production.<ref name="Selikoff" /><ref>Udd, John (1998) {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130509055546/http://www.horton.ednet.ns.ca/staff/webb/geology/3Minerals/Chronology%20of%20Minerals%20in%20Canada.pdf|date=9 May 2013}} National Resources Canada</ref> For a long time, the world's largest asbestos mine was the Jeffrey mine in the town of ].<ref name="Book">{{cite book |editor=Jessica Elzea Kogel |display-editors=etal |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zNicdkuulE4C&pg=PA195|title=Industrial minerals & rocks: commodities, markets, and uses|date=2006|isbn=978-0-87335-233-8|page=195 |publisher=Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration}}</ref> | |||

| Approximately 100,000 people have or will die from asbestos exposure related to ship building. In ], a shipbuilding town, ] occurrence is seven times the national rate.<ref></ref> Thousands of metric tons of asbestos were used in ] ships to wrap the pipes, line the boilers, and cover engine and turbine parts. There were approximately 4.3 million shipyard workers during WWII, for every thousand workers about 14 died of mesothelioma and an unknown number died from asbestosis.<ref name=hamptonroads/> | |||

| ] from 1906]] | |||

| Asbestos fibers were once used in automobile ] and shoes. Since the mid-1990s, a majority of brake pads, new or replacement, have been manufactured instead with ] (] or ]) linings (the same material used in ]s). | |||

| Asbestos production began in the ] of the ] in the 1880s, and the ] of ] with the formation in ] of the Italo-English Pure Asbestos Company in 1876, although this was soon swamped by the greater production levels from the Canadian mines. Mining also took off in ] from 1893 under the aegis of the British businessman Francis Oates, the director of the ] company.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/CORNISH-GEN/2006-11/1164135304|title=Oats, Francis of Golant|date=November 2006|publisher=South African Who's Who 1916|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160601054610/http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/CORNISH-GEN/2006-11/1164135304|archive-date=1 June 2016|access-date=6 June 2014}}</ref> It was in South Africa that the production of amosite began in 1910. The U.S. asbestos industry had an early start in 1858 when fibrous anthophyllite was mined for use as asbestos insulation by the Johns Company, a predecessor to the current ], at a quarry at Ward's Hill on ].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Betts|first=John|date=May–June 2009|title=The Minerals of New York City|url=http://www.johnbetts-fineminerals.com/jhbnyc/articles/nycminerals1.htm|journal=Rocks & Mineral Magazine|volume=84|issue=3|pages=204–252|doi=10.3200/RMIN.84.3.204-223|s2cid=128683529|access-date=21 April 2011}}</ref> US production began in earnest in 1899 with the discovery of large deposits in ] in Vermont. | |||

| ], the first ] on the market, used crocidolite asbestos in its "Micronite" filter from 1952 to 1956.<ref>] </ref> | |||

| The use of asbestos became increasingly widespread toward the end of the 19th century when its diverse applications included fire-retardant coatings, concrete, bricks, pipes and fireplace cement, heat-, fire-, and acid-resistant gaskets, pipe insulation, ceiling insulation, fireproof drywall, flooring, roofing, lawn furniture, and drywall joint compound. In 2011, it was reported that over 50% of UK houses still contained asbestos, despite a ban on asbestos products some years earlier.<ref name="guardian2011">Don, Andrew (1 May 2011) . ''The Guardian''.</ref> | |||

| The first documented death related to asbestos was in 1906.<ref name="MC"/> In the early 1900's researchers began to notice a large number of early deaths and lung problems in asbestos mining towns. The first diagnosis of ] was made in England in 1924.<ref name="resource_center"/> England protected asbestos workers about ten years faster than the US, by the 1930s England regulated ventilation and made asbestos an excusable work related disease.<ref name="resource_center"/><ref name="ACS"></ref> The term ] was not used in medical literature until 1931, and wasn't associated with asbestos until sometime in the 1940's.<ref name="MC"/> | |||

| In Japan, particularly after ], asbestos was used in the manufacture of ] for purposes of rice production, sprayed upon the ceilings, iron skeletons, and walls of railroad cars and buildings (during the 1960s), and used for energy efficiency reasons as well. Production of asbestos in Japan peaked in 1974 and went through ups and downs until about 1990 when production began to drop dramatically.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hvbg.de/e/asbest/konfrep/konfrep/repbeitr/morinaga_en.pdf|title=Asbestos in Japan|author=Morinaga, Kenji|work=European Conference 2003|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110719043338/http://www.hvbg.de/e/asbest/konfrep/konfrep/repbeitr/morinaga_en.pdf|archive-date=19 July 2011|access-date=12 January 2010}}</ref> | |||

| The United States government and asbestos industry have been criticized for not acting fast enough to inform the public of dangers, and reduce public exposure. In the late 1970's court documents proved that asbestos industry officials knew of asbestos dangers and tried to conceal them.<ref name=hamptonroads/> | |||

| ===Discovery of toxicity=== | |||

| In Japan, particularly after ], asbestos was used in the manufacture of ammonium sulfate for purposes of rice production, sprayed upon the ceilings, iron skeletons, and walls of railroad cars and buildings (during the 1960s), and used for energy efficiency reasons as well. Production of asbestos in Japan peaked in 1974 and went through ups and downs until about 1990, when production began to drop severely.<ref></ref> | |||

| {{for|additional chronological citations|List of asbestos disease medical articles}} | |||

| The 1898 Annual Report of the Chief Inspector of Factories and Workshops in the United Kingdom noted the negative health effects of asbestos,<ref>{{cite web |title=PDF link to relevant page of report |url=https://www.rochdaleonline.co.uk/uploads/f1/news/document/2008911_16159.pdf}}</ref> the contribution having been made by ], one of the first women ]s. | |||

| In 1899, H. Montague Murray noted the negative health effects of asbestos.<ref name="nih_mp">{{Cite journal|last1=Luus|first1=K|year=2007|title=Asbestos: Mining exposure, health effects and policy implications|journal=McGill Journal of Medicine|volume=10|issue=2|pages=121–6|pmc=2323486|pmid=18523609}}</ref> The first documented death related to asbestos was in 1906.<ref name="svdell_hist">{{cite web|url=http://www.silverdell.plc.uk/images/downloads/Silverdell_History_of_Asbestos.pdf|title=The History of Asbestos in the UK – The story so far ... Asbestos uses and regulations timeline|date=30 April 2012|publisher=silverdell.plc.uk|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131021061734/http://www.silverdell.plc.uk/images/downloads/Silverdell_History_of_Asbestos.pdf|archive-date=21 October 2013}}</ref> | |||

| In the early 1900s, researchers began to notice a large number of early deaths and lung problems in asbestos-mining towns. The first such study was conducted by Murray at the ], ], in 1900, in which a postmortem investigation discovered asbestos traces in the lungs of a young man who had died from ] after having worked for 14 years in an asbestos textile factory. ], the Inspector of Factories in Britain, included asbestos in a list of harmful industrial substances in 1902. Similar investigations were conducted in France in 1906 and Italy in 1908.<ref name="Selikoff2">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ARKaW4uP9BgC|title=Asbestos and Disease|author=Selikoff, Irving J.|publisher=Elsevier|year=1978|isbn=978-0-323-14007-2|pages=20–32}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ]'', 1926]] | |||

| The first diagnosis of ] was made in the UK in 1924.<ref name="svdell_hist" /><ref name="cooke">{{Cite journal|last=Cooke|first=W.E.|date=26 July 1924|journal=]|location=London|publisher=]|volume=2|issue=3317|pages=140–2, 147|doi=10.1136/bmj.2.3317.147|issn=0959-8138|pmc=2304688|pmid=20771679|title=Fibrosis of the Lungs Due to the Inhalation of Asbestos Dust}}</ref><ref name="selikoff">{{Cite journal|last1=Selikoff|first1=Irving J.|last2=Greenberg|first2=Morris|date=20 February 1991|title=A Landmark Case in Asbestosis|url=http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/reprint/265/7/898.pdf|journal=]|location=Chicago, Illinois|publisher=]|volume=265|issue=7|pages=898–901|doi=10.1001/jama.265.7.898|issn=0098-7484|pmid=1825122|access-date=20 April 2010}}</ref> ] was employed at ] in ], ], ], from 1917, spinning raw asbestos fibre into yarn.<ref name="selikoff" /><ref name="dusty">{{Cite book|title=The Way from Dusty Death: Turner and Newall and the Regulation of the British Asbestos Industry 1890s–1970|last=Bartrip|first=P.W.J.|publisher=The Athlone Press|year=2001|isbn=978-0-485-11573-4|location=London|page=12}}</ref> Her death in 1924 led to a formal inquest. ] William Edmund Cooke testified that his examination of the lungs indicated old scarring indicative of a previous, healed ] infection, and extensive ], in which were visible "particles of mineral matter ... of various shapes, but the large majority have sharp angles."<ref name="cooke" /> Having compared these particles with samples of asbestos dust provided by S. A. Henry, His Majesty's Medical Inspector of Factories, Cooke concluded that they "originated from asbestos and were, beyond a reasonable doubt, the primary cause of the fibrosis of the lungs and therefore of death."<ref name="selikoff" /><ref name="bartrip">{{Cite journal|last=Bartrip|first=Peter|year=1998|title=Too little, too late? The home office and the asbestos industry regulations, 1931|journal=Med. Hist.|location=London|publisher=The Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL|volume=42|issue=4|pages=421–438|doi=10.1017/s0025727300064334|issn=0025-7273|pmc=1044071|pmid=10505397}}</ref> | |||

| As a result of Cooke's paper, ] commissioned an inquiry into the effects of asbestos dust by E. R. A. Merewether, Medical Inspector of Factories, and {{nowrap|C. W. Price}}, a ] and pioneer of dust monitoring and control.<ref name="gee">{{Cite journal|last1=Gee|first1=David|last2=Greenberg|first2=Morris|date=9 January 2002|title=Asbestos: from 'magic' to malevolent mineral|url=http://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/environmental_issue_report_2001_22/issue-22-part-05.pdf|journal=Late Lessons from Early Warnings: The Precautionary Principle 1896–2000|location=Copenhagen|publisher=]|issue=22|pages=52–63|isbn=978-92-9167-323-0|access-date=20 April 2010}}</ref> Their subsequent report, ''Occurrence of Pulmonary Fibrosis & Other Pulmonary Affections in Asbestos Workers'', was presented to Parliament on 24 March 1930.<ref>Published as ''Report on the effects of asbestos dust on the lungs and dust suppression in the asbestos industry. Part I. Occurrence of pulmonary fibrosis and other pulmonary affections in asbestos workers. Part II. Processes giving rise to dust and methods for its suppression.'' London: ], 1930.</ref> It concluded that the development of asbestosis was irrefutably linked to the prolonged inhalation of asbestos dust, and included the first health study of asbestos workers, which found that 66% of those employed for 20 years or more suffered from asbestosis.<ref name="gee" /> The report led to the publication of the first asbestos industry regulations in 1931, which came into effect on 1 March 1932.<ref name="sb_classpap">{{cite web|url=http://scienceblogs.com/thepumphandle/2012/11/27/classic-papers-in-public-health-annual-report-of-the-chief-inspector-of-factories-for-the-year-1947-by-e-r-a-merewether/|title=Classic papers in Public Health: Annual Report of the Chief Inspector of Factories for the Year 1947 by E.R.A. Merewether – The Pump Handle|date=21 October 2013|publisher=scienceblogs.com|access-date=21 October 2013}}</ref> These rules regulated ventilation and made asbestosis an excusable work-related disease.<ref name="qsqlui" /> The term ] was first used in medical literature in 1931; its association with asbestos was first noted sometime in the 1940s. Similar legislation followed in the U.S. about ten years later. | |||

| Approximately 100,000 people in the United States have died, or are terminally ill, from asbestos exposure related to shipbuilding.{{Citation needed|date=April 2024}} In the ] area, a shipbuilding center, mesothelioma occurrence is seven times the national rate.<ref>Burke, Bill (6 May 2001) ''Virginian-Pilot'' Norfolk, Virginia (newspaper); from ]</ref> Thousands of tons of asbestos were used in World War II ships to insulate piping, boilers, steam engines, and steam turbines. There were approximately 4.3 million shipyard workers in the United States during the war; for every 1,000 workers, about 14 died of mesothelioma and an unknown number died of asbestosis.<ref name="hamptonroads">Burke, Bill (6 May 2001) ''Virginian-Pilot'' Norfolk, Virginia (newspaper)</ref> | |||

| The United States government and the asbestos industry have been criticized for not acting quickly enough to inform the public of dangers and to reduce public exposure. In the late 1970s, court documents proved that asbestos industry officials knew of asbestos dangers since the 1930s and had concealed them from the public.<ref name="hamptonroads" /> | |||

| In Australia, asbestos was widely used in construction and other industries between 1946 and 1980. From the 1970s, there was increasing concern about the dangers of asbestos, and following community and union campaigning, its use was phased out, with mining having ceased in 1983.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Commons Librarian |date=2023-12-22 |title=Campaigns that Changed Western Australia |url=https://commonslibrary.org/campaigns-that-changed-western-australia/ |access-date=2024-04-19 |website=The Commons Social Change Library |language=en-AU}}</ref> The use of asbestos was phased out in 1989 and banned entirely in December 2003. The dangers of asbestos are now well known in Australia, and there is help and support for those suffering from asbestosis or mesothelioma.<ref>Lavelle, Peter (29 April 2004) . Australian Broadcasting Corporation</ref> | |||

| ===Use by industry and product type=== | |||

| {{more citations needed section|date=April 2018}} | |||

| ===Modern usage=== | |||

| ====Serpentine group==== | ====Serpentine group==== | ||

| ], London, 1941, nurses arrange asbestos blankets over an electrically heated frame to create a hood over patients to help warm them quickly]] | |||

| ] minerals have a sheet or layered structure. ] (commonly known as white asbestos) is the only asbestos mineral in the serpentine group. In the United States, chrysotile has been the most commonly used type of asbestos. According to the U.S. ] (EPA) Asbestos Building Inspectors Manual, chrysotile accounts for approximately 95% of asbestos found in buildings in the United States.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Franck |first1=Harold |last2=Franck |first2=Darren |title=Forensic Engineering Fundamentals |date=2016 |publisher=CRC Press |location=Boca Raton FL |isbn=978-1-4398-7840-8 |page=103 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mgfSBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA103}}</ref> Chrysotile is often present in a wide variety of products and materials, including: | |||

| * Chlor Alkali diaphragm membranes ] (currently in the US)<ref>. Olin Corporation</ref> | |||

| * ] and joint compound (including texture coats) | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Gas mask filters throughout World War II until the 1960s for most countries; Germany and the USSR's Civilian issued filters up until 1988 tested positive for asbestos | |||

| * Vinyl floor tiles, sheeting, adhesives | |||

| * Roofing tars, felts, siding, and shingles<ref>{{cite journal|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=td4DAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA62|title=Popular Mechanics|author=Hearst Magazines|journal=Popular Mechanics |date=July 1935|publisher=Hearst Magazines|page=62|issn=0032-4558|access-date=10 January 2012}}</ref> | |||

| * "]" panels, siding, countertops, and pipes | |||

| * ]s, also known as acoustic ceilings | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Industrial and marine ]s | |||

| * ] pads and shoes | |||

| * Stage curtains | |||

| * Fire blankets | |||

| * Cement pipework | |||

| * Interior fire doors | |||

| * Fireproof clothing for firefighters | |||

| * Thermal pipe insulation | |||

| * Filters for removing fine particulates from chemicals, liquids, and wine | |||

| * Dental cast linings | |||

| * HVAC flexible duct connectors | |||

| * ] additives | |||

| In the European Union and Australia, it has been banned as a potential health hazard<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ascc.gov.au/ascc/NewsEvents/MediaReleases/2001/NOHSCdeclaresprohibitiononuseofchrysotileasbestos.htm |title=NOHSC declares prohibition on use of chrysotile asbestos |date=17 October 2001 |publisher=Ascc.gov.au |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080607010556/http://www.ascc.gov.au/ascc/NewsEvents/MediaReleases/2001/NOHSCdeclaresprohibitiononuseofchrysotileasbestos.htm |archive-date=7 June 2008 }}</ref> and is no longer used at all. | |||

| <gallery widths="200px" heights="200px"> | |||

| Serpentine minerals have a sheet or layered structure. Chrysolite is the only asbestos mineral in the serpetine group. In the ], chrysotile has been the most commonly used type of asbestos. According to the U.S. EPA Asbestos Building Inspectors Manual, Chrysotile accounts for approximately 95% of asbestos found in buildings in the United States. Chrysotile is often present in a wide variety of materials, including : | |||

| File:Arcon mk post-war pre-fab.jpg|Example of ] siding and lining on a post-war temporary house in ]. Nearly 40,000 of these structures were built between 1946 and 1949 to house families | |||

| <div class="references-small" style="-moz-column-count:2; column-count:2;"> | |||

| File:Heat-resistant asbestos glove.jpg|An asbestos glove | |||

| * joint compound | |||

| File:M60 machine gun barrel change DF-ST-90-04667.jpg| The ] crew member responsible for a hot barrel change was issued protective asbestos gloves to prevent burns to the hands | |||

| * mud and texture coats | |||

| File:AsbestosHeatSpreaderForCooking.jpg|A household heat spreader for cooking on gas stoves, made of asbestos (probably 1950s; "{{lang|fr|amiante pur}}" is French for "pure asbestos") | |||

| * vinyl floor tiles, sheeting, adhesives | |||

| File:Asbesthaltige Flachdichtungen.jpg|Gasket, containing nearly unbound asbestos | |||

| * roofing tars, felts, siding, and shingles | |||

| File:Asbestos pipe 'REAL ASBESTOS BEST QUALITY'.jpg|Asbestos pipe for tobacco smoking from Belgium, with inscription "Real asbestos best quality". | |||

| * "transite" panels, siding, countertops, and pipes | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ]s | |||

| * ] pads and shoes | |||

| * ] plates | |||

| * stage curtains | |||

| * fire blankets | |||

| * interior fire doors | |||

| * fireproof clothing for firefighters | |||

| * thermal pipe insulation | |||

| </div> | |||

| In the ] and ] it has recently been banned as a potential health hazard<ref></ref> and is not used at all. ] is moving in the same direction, but more slowly. Revelations that hundreds of workers had died in Japan over the previous few decades from diseases related to asbestos sparked a scandal in mid-2005.<ref name=Iceberg> Japan Times Online</ref> Tokyo had, in 1971, ordered companies handling asbestos to install ventilators and check health on a regular basis; however, the Japanese government did not ban crocidolite and amosite until 1995, and a full-fledged ban on asbestos was implemented in October 2004.<ref name=Iceberg/> | |||

| ====Amphibole group==== | ====Amphibole group==== | ||

| ]s including ] (brown asbestos) and ] (blue asbestos) were formerly used in many products until the early 1980s. {{citation needed|date=August 2012}} ] asbestos constituted a contaminant of many if not all naturally occurring chrysotile deposits. The use of all types of asbestos in the amphibole group was banned in much of the Western world by the mid-1980s, and in Japan by 1995.<ref>{{Cite web | url=http://www.umt.edu/bioethics/libbyhealth/Resources/Legal%20Resources/international_ban_asbestos.aspx |title = International Bans on Asbestos Use – Asbestos and Libby Health – the University of Montana}}</ref> Some products that included amphibole types of asbestos included the following: | |||

| FIve types of asbestos are found in the amphibole group: Amosite, Crocidolite, Anthophyllite, Tremolite, and Actinolite. Amosite, the second most likely type to be found in buildings, according to the U.S. EPA Asestos Building Inspectors Guide, is the "brown" asbestos. | |||

| * Low-density insulating board (often referred to as AIB or asbestos insulating board) and ceiling tiles; | |||

| * ] sheets and pipes for construction, casing for water and electrical/telecommunication services; | |||

| * Thermal and chemical insulation (e.g., fire-rated doors, limpet spray, lagging, and gaskets). | |||

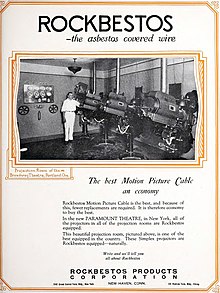

| * Electrical wiring, braided cables, cable wrap, wire insulation (usually ]) | |||

| Cigarette manufacturer ] (] ]) used crocidolite asbestos in its "Micronite" filter from 1952 to 1956.<ref>. Snopes.com. Retrieved 10 January 2012.</ref> | |||

| Amosite and crocidolite were formally used in many products until the early ]. The use of all types of asbestos in the amphibole group was banned (in much of the Western world) by the mid-1980s, and by Japan in 1995. These products were mainly: | |||

| *Low density insulation board and ceiling tiles | |||

| *] sheets and pipes for construction, casing for water and electrical/telecommunication services | |||

| *thermal and chemical insulation (''i.e.'', fire rated doors, limpet spray, lagging and gaskets) | |||

| While mostly chrysotile asbestos fibers were once used in automobile ], shoes, and ], contaminants of amphiboles were present. Since approximately the mid-1990s, brake pads, new or replacement, have been manufactured instead with linings made of ceramic, carbon, metallic, and ] (] or ]—the same material used in ]s). | |||

| {{globalize/US and Canada}} | |||

| Artificial Christmas snow, known as flocking, was previously made with asbestos.<ref>{{cite book|title=1001 unbelievable Facts|last=Otway|first=Helen|publisher=Capella|year=2005|isbn=978-1-84193-783-0|page=191|chapter=Unbelievable Random Facts}}</ref> It was used as an effect in films including '']'' and department store window displays and it was marketed for use in private homes under brand names that included "Pure White", "Snow Drift" and "White Magic".<ref name="ems">. Retrieved 19 December 2014</ref> | |||

| ==Health issues== | |||

| ===Potential use in carbon sequestration=== | |||

| The first signs of health related concerns associated with Asbestos fibers was likely late 1800s/early 1900s. Asbestos diseases can be seen as early as 10 years after exposure. As such, with asbestos mining, manufacturing and installation in full gear by the late 1800s, it is likely that asbestos related sickness/illness was present and diagnosed, though not named until later in 1900s. | |||

| The potential for use of asbestos to ] has been raised. Although the adverse aspects of mining of minerals, including health effects, must be taken into account, exploration of the use of mineral wastes to ] is being studied. The use of ] materials from ], ], ], and ] mines have the potential as well, but asbestos may have the greatest potential and is the subject of research now in progress in an emerging field of scientific study to examine it. The most common type of asbestos, chrysotile, chemically reacts with CO<sub>2</sub> to produce ecologically stable ]. ], like all types of asbestos, has a large surface area that provides more places for chemical reactions to occur, compared to most other naturally occurring materials.<ref>Temple, James, '''', MIT Technology Review, October 6, 2020</ref> | |||

| === |

===Construction=== | ||

| ====Developed countries==== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ], for ] for residential building construction]] | |||

| The use of asbestos in new construction projects has been banned for health and safety reasons in many developed countries or regions, including the European Union, the United Kingdom, Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, and New Zealand. A notable exception is the United States, where asbestos continues to be used in construction such as cement asbestos pipes.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} The ] prevented the EPA from banning asbestos in 1991 because EPA research showed the ban would cost between US$450 and 800 million while only saving around 200 lives in a 13-year timeframe, and that the EPA did not provide adequate evidence for the safety of alternative products.<ref>. Openjurist.org. Retrieved 10 January 2012.</ref> Until the mid-1980s, small amounts of white asbestos were used in the manufacture of ], a decorative stipple finish,<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170611224259/http://www.asbestossurveyingltd.co.uk/where_asbestos_ceiling_artex.htm |date=11 June 2017 }}. Retrieved 29 December 2008.</ref> however, some of the lesser-known suppliers of Artex-type materials were still adding white asbestos until 1999.<ref>, Click the "Asbestos in Artex" button.</ref> | |||

| Before the ban, asbestos was widely used in the construction industry in thousands of materials. Some are judged to be more dangerous than others due to the amount of asbestos and the material's friable nature. Sprayed coatings, pipe insulation, and ] (AIB) are thought to be the most dangerous due to their high content of asbestos and friable nature. Many older buildings built before the late 1990s contain asbestos. In the United States, there is a minimum standard for asbestos surveys as described by ] standard E 2356–18. In the UK, the ] have issued guidance called HSG264 describing how surveys should be completed although other methods can be used if they can demonstrate they have met the regulations by other means.<ref>{{cite book|url=http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/books/hsg264.htm|title=Asbestos: The survey guide |publisher=House and Safety Executive |date=2012 |edition=Second |access-date=12 September 2022 |isbn=978-0-7176-6502-0}}</ref> The EPA includes some, but not all, asbestos-contaminated facilities on the ] (NPL). Renovation and demolition of asbestos-contaminated buildings are subject to EPA ] and OSHA Regulations. Asbestos is not a material covered under ]'s innocent purchaser defense. In the UK, the removal and disposal of asbestos and substances containing it are covered by the ].<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.hse.gov.uk/asbestos/regulations.htm |title=''Control of Asbestos Regulations 2006'', Health and Safety Executive, London, UK, Undated. Retrieved 29 December 2008. |access-date=29 December 2008 |archive-date=19 May 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090519080718/http://www.hse.gov.uk/asbestos/regulations.htm |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| In 1918, a Prudential Insurance Company official notes that life insurance companies will not cover asbestos workers, because of the "health-injurious conditions of the industry".<ref name=Castleman> | |||

| {{cite book|author=Barry I. Castleman|title=Asbestos:Medical and Legal Aspects|edition=4th Edition|publisher=Aspen Law & Business|year=1996|id=ISBN 1-56706-275-X}}</ref> | |||

| U.S. asbestos consumption hit a peak of 804,000 tons in 1973; world asbestos demand peaked around 1977, with 25 countries producing nearly 4.8 million metric tons annually.<ref>{{citation|title=History of Asbestos|url=http://www.asbestos.com/asbestos/history/|publisher=Asbestos.com|access-date=7 April 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ===1930s=== | |||

| In older buildings (e.g. those built before 1999 in the UK, before white asbestos was banned), asbestos may still be present in some areas. Being aware of asbestos locations reduces the risk of disturbing asbestos.<ref name="Wrekin housing trust pdf">{{cite web|url=http://www.wrekinhousingtrust.org.uk/publications/leaflets/Asbestos%20in%20the%20Home%20Booklet%2006-20061.pdf|title=Asbestos in the home booklet. Wrekin housing trust.|access-date=26 October 2010}}</ref> | |||

| In 1930, the major asbestos company Johns-Manville produces a report, for internal company use only, about medical reports of asbestos worker fatalities.<ref name=Castleman/> In 1932, A letter from U.S. Bureau of Mines to asbestos manufacturer Eagle-Picher states, in relevant part, "It is now known that asbestos dust is one of the most dangerous dusts to which man is exposed".<ref name=Brodeur>{{citebook|author=Paul Brodeur|title=Outrageous Misconduct: The Asbestos Industry on Trial|edition=1st Edition|publisher=Pantheon Books|year=1985|id=ISBN 0-394-53320-8}}</ref> In 1933, Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. doctors find that 29 percent of workers in a Johns-Manville plant have asbestosis.<ref name=Castleman/> Likewise, in 1933, Johns-Manville officials settle lawsuits by 11 employees with asbestosis on the condition that the employees' lawyer agree to never again "directly or indirectly participate in the bringing of new actions against the Corporation."<ref name=Brodeur/> In 1934, officials of two large asbestos companies, Johns-Manville and Raybestos-Manhattan, edit an article about the diseases of asbestos workers written by a Metropolitan Life Insurance Company doctor. The changes minimize the danger of asbestos dust.<ref name=Brodeur/> In 1935, officials of Johns-Manville and Raybestos-Manhattan instruct the editor of Asbestos magazine to publish nothing about asbestosis.<ref name=Brodeur/> In 1936, a group of asbestos companies agrees to sponsor research on the health effects of asbestos dust, but require that the companies maintain complete control over the disclosure of the results.<ref name=Castleman/> | |||

| Removal of asbestos building components can also remove the fire protection they provide, therefore fire protection substitutes are required for proper fire protection that the asbestos originally provided.<ref name="Wrekin housing trust pdf" /><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120829191651/http://www.sandwell.gov.uk/info/415/pollution_control-asbestos/483/asbestos_removal |date=29 August 2012 }}. Laws.sandwell.gov.uk (1 April 2005). Retrieved 10 January 2012.</ref> | |||

| ===1940s=== | |||

| ====Outside Europe and North America==== | |||

| In 1942, an internal Owens-Corning corporate memo refer to "medical literature on asbestosis . . . . scores of publications in which the lung and skin hazards of asbestos are discussed."<ref>Barry I. Castleman, Asbestos: Medical and Legal Aspects, 4th edition, Aspen Law and Business, Englewood Cliffs, NJ 1996, p.195</ref>. Either in 1942 or 1943, the president of Johns-Manville says that the managers of another asbestos company were "a bunch of fools for notifying employees who had asbestosis." When one of the managers asks, "do you mean to tell me you would let them work until they dropped dead?" The response is reported to have been, "Yes. We save a lot of money that way."<ref>.Testimony of Charles H. Roemer, Deposition taken April 25, 1984, Johns-Manville Corp., et al v. the United States of America, U.S. Claims Court Civ. No. 465-83C, cited in Barry I. Castleman, Asbestos: Medical and Legal Aspects, 4th edition, Aspen Law and Business, Englewood Cliffs, NJ 1996, p.581</ref>. In 1944, a Metropolitan Life Insurance Company report finds 42 cases of asbestosis among 195 asbestos miners.<ref>.Barry I. Castleman, Asbestos: Medical and Legal Aspects, 4th edition, Aspen Law and Business, Englewood Cliffs, NJ 1996, p.654</ref>. | |||

| Some countries, such as ], Indonesia, China and Russia, have continued widespread use of asbestos. The most common is corrugated asbestos-cement sheets or "A/C sheets" for roofing and sidewalls. Millions of homes, factories, schools or sheds, and shelters continue to use asbestos. Cutting these sheets to size and drilling holes to receive 'J' bolts to help secure the sheets to roof framing is done on-site. There has been no significant change in production and use of A/C sheets in ] following the widespread restrictions in developed nations.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Globalization: Threat or Opportunity? An IMF Issues Brief |url=https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/ib/2000/041200to.htm |access-date=2023-10-21 |website=www.imf.org}}</ref> | |||

| === |

====September 11 attacks==== | ||

| {{See also|Health effects arising from the September 11 attacks}} | |||

| As ]'s ] collapsed following the ], ] was blanketed in a mixture of building debris and combustible materials. This complex mixture gave rise to the concern that thousands of residents and workers in the area would be exposed to known hazards in the air and dust, such as asbestos, lead, glass fibers, and pulverized concrete.<ref name="stephenson2007">{{cite book|title=World Trade Center: preliminary observations on EPA's second program to address indoor contamination (GAO-07-806T): testimony before the Subcommittee on Superfund and Environmental Health, U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works|last=Stephenson|first=John B.|date=20 June 2007|publisher=U.S. ]|location=Washington, D.C.}}</ref> More than 1,000 tons of asbestos are thought to have been released into the air following the buildings' destruction.<ref name="tg20091111">{{cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/nov/11/cancer-new-york-rescuers|title=9/11's delayed legacy: cancer for many of the rescue workers|last=Pilkington|first=Ed|date=11 November 2009|newspaper=The Guardian|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170512181338/https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/nov/11/cancer-new-york-rescuers|archive-date=12 May 2017|location=London}}</ref> Inhalation of a mixture of asbestos and other toxicants is thought to be linked to the unusually high death rate from cancer of emergency service workers since the disaster.<ref name="tg20091111" /> Thousands more are now thought to be at risk of developing cancer due to this exposure with those who have died so far being only the "tip of the iceberg".<ref name="tg20091111" /> | |||

| In May 2002, after numerous cleanup, dust collection, and air monitoring activities were conducted outdoors by EPA, other federal agencies, New York City, and the state of New York, New York City formally requested federal assistance to clean and test residences in the vicinity of the World Trade Center site for airborne asbestos.<ref name="stephenson2007" /> | |||

| In 1951, Asbestos companies remove all references to cancer before allowing publication of research they sponsor.<ref>Barry I. Castleman, Asbestos: Medical and Legal Aspects, 4th edition, Aspen Law and Business, Englewood Cliffs, NJ 1996, p.71</ref>. In 1952, | |||

| Dr. Kenneth Smith, Johns-Manville medical director, recommends (unsuccessfully) that warning labels be attached to products containing asbestos. Later Smith testifies: "It was a business decision as far as I could understand . . . the corporation is in business to provide jobs for people and make money for stockholders and they had to take into consideration the effects of everything they did and if the application of a caution label identifying a product as hazardous would cut into sales, there would be serious financial implications."<ref>Barry I. Castleman, Asbestos: Medical and Legal Aspects, 4th edition, Aspen Law and Business, Englewood Cliffs, NJ 1996, p.666</ref>. In 1953, National Gypsum's safety director writes to the Indiana Division of Industrial Hygiene, recommending that acoustic plaster mixers wear respirators "because of the asbestos used in the product." Another company official notes that the letter is "full of dynamite," urges that it be retrieved before reaching its destination. A memo in the files notes that the company "succeeded in stopping" the letter, which "will be modified."<ref>Barry I. Castleman, Asbestos: Medical and Legal Aspects, 4th edition, Aspen Law and Business, Englewood Cliffs, NJ 1996, p.669-70</ref>. | |||

| ===Asbestos contaminants in other products=== | |||

| ====Vermiculite==== | |||

| ] is a hydrated laminar magnesium-aluminum-iron silicate that resembles ]. It can be used for many industrial applications and has been used as insulation. Some deposits of vermiculite are contaminated with small amounts of asbestos.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.epa.gov/asbestos/pubs/verm.html|title=EPA Asbestos Contamination in Vermiculite|date=28 June 2006|publisher=Epa.gov|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100111080049/http://www.epa.gov/asbestos/pubs/verm.html|archive-date=11 January 2010|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| One vermiculite mine operated by ] in ] exposed workers and community residents to danger by mining vermiculite contaminated with asbestos, typically ], winchite, ] or ].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Meeker|first=G.P|year=2003|title=The Composition and Morphology of Amphiboles from the Rainy Creek Complex, Near Libby, Montana|url=https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/70024962|journal=American Mineralogist|volume=88|issue=11–12|pages=1955–1969|bibcode=2003AmMin..88.1955M|doi=10.2138/am-2003-11-1239|s2cid=12134481}}</ref> Vermiculite contaminated with asbestos from the Libby mine was used as insulation in residential and commercial buildings through Canada and the United States. W. R. Grace and Company's loose-fill vermiculite was marketed as ] but was also used in sprayed-on products such as ]. | |||

| ===Asbestos as a contaminant=== | |||

| In 1999, the EPA began cleanup efforts in Libby and now the area is a ] cleanup area.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.epa.gov/region8/superfund/libby/|title=Libby Asbestos – US EPA Region 8|publisher=Epa.gov|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100205101037/http://www.epa.gov/region8/superfund/libby/|archive-date=5 February 2010|access-date=12 January 2010}}</ref> The EPA has determined that harmful asbestos is released from the mine as well as through other activities that disturb soil in the area.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.epa.gov/region8/superfund/libby/risk.html|title=Risk Assessment – US EPA|date=22 December 2008|publisher=Epa.gov}}</ref> | |||

| Most respirable asbestos fibers are invisible to the unaided ] because their size is about 3.0-20.0 ] in length and can be as thin as 0.01 µm. ] ranges in size from 17 to 181 µm in width.<ref></ref> Fibers ultimately form because when these minerals originally cooled and crystallized, they formed by the ]ic molecules lining up parallel with each other and forming oriented ]. These crystals thus have three ], just as other minerals and gemstones have. But in their case, there are two cleavage planes that are much weaker than the third direction. When sufficient force is applied, they tend to break along their weakest directions, resulting in a linear fragmentation pattern and hence a fibrous form. This fracture process can keep occurring and one larger asbestos fiber can ultimately become the source of hundreds of much thinner and smaller fibers. | |||

| ====Talc==== | |||

| As asbestos fibers get smaller and lighter, the more easily they become airborne and human respiratory exposures can result. Fibers will eventually settle but may be re-suspended by air currents or other movement. | |||

| ] made of asbestos, on a tripod over a ]]] | |||

| ] can sometimes be contaminated with asbestos due to the proximity of asbestos ore (usually ]) in underground talc deposits.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2004/1092/|title=A USGS Study of Talc Deposits and Associated Amphibole Asbestos Within Mined Deposits of the Southern Death Valley Region, California |author=Van Gosen, Bradley S. |author2=Lowers, Heather A. |author3=Sutley, Stephen J.|year=2004|publisher=Pubs.usgs.gov}}</ref> By 1973, US federal law required all talc products to be asbestos-free.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/feb/29/is-it-safe-to-use-talcum-baby-powder-ovarian-cancer-johnson-johnson|title=Is it safe to use talcum powder?|last=Dillner|first=Luisa|date=29 February 2016|newspaper=The Guardian|access-date=2017-04-03|language=en-GB|issn=0261-3077}}</ref> Separating ] talc (e.g. talcum powder) from ] talc (often used in friction products) has largely eliminated this issue for consumers.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.straightdope.com/columns/read/996/is-talcum-powder-asbestos|title=The Straight Dope: Is talcum powder asbestos?|website=www.straightdope.com|date=16 February 1990|language=en|access-date=2017-04-03}}</ref> Cosmetics companies, including Johnson & Johnson, have known since the 1950s that talc products could be contaminated with asbestos.<ref name=":2">{{Cite web |date=2023-05-05 |title=Cosmetics companies face major concern over asbestos contamination of talc {{!}} Environmental Working Group |url=https://www.ewg.org/news-insights/news/2023/05/cosmetics-companies-face-major-concern-over-asbestos-contamination-talc |access-date=2024-09-06 |website=www.ewg.org |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Girion |first=Lisa |date=December 14, 2018 |title=J&J knew for decades that asbestos lurked in its baby powder |url=https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/johnsonandjohnson-cancer/ }}</ref> In 2020, laboratory tests of 21 talc-based cosmetics products found that 15 percent were contaminated with asbestos.<ref name=":2" /> In July 2024, the World Health Organization (WHO) heightened its health warning about talc exposure. In a study published in The Lancet, the WHO changed its classification of talc from "possibly carcinogenic" to "probably carcinogenic."<ref>{{Cite web |title=WHO: Talc 'Probably Carcinogenic' to Humans |url=https://www.drugwatch.com/news/2024/07/09/who-talc-probably-carcinogenic-to-humans/ |access-date=2024-09-06 |website=Drugwatch.com |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| In 2000, tests in a certified asbestos-testing laboratory found the tremolite form of amphibole asbestos used to be found in three out of eight popular brands of children's ]s that were made partly from talc: ], Prang, and RoseArt.<ref name="seattlepi-a">{{cite news|url=http://www.commondreams.org/headlines/052300-02.htm|title=Major brands of kids' crayons contain asbestos, tests show|date=23 May 2000|work=]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120304003203/http://www.commondreams.org/headlines/052300-02.htm|archive-date=4 March 2012}}</ref> In Crayola crayons, the tests found asbestos levels around 0.05% in ''Carnation Pink'' and 2.86% in ''Orchid''; in Prang crayons, the range was from 0.3% in ''Periwinkle'' to 0.54% in ''Yellow''; in Rose Art crayons, it was from 0.03% in ''Brown'' to 1.20% in ''Orange''. Overall, 32 different types of crayons from these brands used to contain more than trace amounts of asbestos, and eight others contained trace amounts. The ], a ] which tested the safety of crayons on behalf of the makers, initially insisted the test results must have been incorrect, although they later said they do not test for asbestos.<ref name="seattlepi-a" /> In May 2000, Crayola said tests by Richard Lee, a materials analyst whose testimony on behalf of the asbestos industry has been accepted in lawsuits over 250 times, found its crayons tested negative for asbestos.<ref name="seattlepi-b">{{cite news|url=http://www.carollsmith.com/pdf/crayonfirm.pdf|title=Crayon firms agree to stop using talc|author1=Schneider, Andrew|date=13 June 2000|work=]|author2=Smith, Carol|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120713182250/http://www.carollsmith.com/pdf/crayonfirm.pdf|archive-date=13 July 2012}}</ref> In spite of that, in June 2000 Binney & Smith, the maker of Crayola, and the other makers agreed to stop using talc in their products, and changed their product formulations in the United States.<ref name="seattlepi-b" /> | |||

| Friability of a product containing asbestos means that it is so soft and weak in structure that it can be broken with simple finger crushing pressure. Friable materials are of the most initial concern due to their ease of damage. The forces or conditions of usage that come into intimate contact with most non-friable materials containing asbestos are substantially higher than finger pressure. | |||

| The mining company R T Vanderbilt Co of ], which supplied the talc to the crayon makers, states that "to the best of our knowledge and belief" there had never been any asbestos-related disease among the company's workers.<ref name="seattlepi-c">{{cite news |last1=Schneider |first1=Andrew |last2=Smith |first2=Carol |url=https://www.upstate.edu/pathenvi/studies/cases/ny_talc_dispute.pdf|title=Old dispute rekindled over content of mine's talc|date=30 May 2000|work=]|access-date=7 March 2021}}</ref> However media reports claim that the ] (MSHA) had found asbestos in four talc samples tested in 2000.<ref name="seattlepi-a" /> The Assistant Secretary for Mine Safety and Health subsequently wrote to the news reporter, stating that "In fact, the abbreviation ND (non-detect) in the laboratory report – indicates no asbestos fibers actually were found in the samples."<ref>McAteer, J. Davitt Assist. Secretary for Mine Safety and Health correspondence to Andrew Schneider of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer dated 14 June 2000 – copy obtainable through records archives MSHA.</ref> Multiple studies by mineral chemists, cell biologists, and toxicologists between 1970 and 2000 found neither samples of asbestos in talc products nor symptoms of asbestos exposure among workers dealing with talc,<ref>For studies finding no asbestos in talcum powder samples, see: | |||

| ===Naturally occurring asbestos=== | |||

| * Van Orden, D., R. J. Lee: Weight Percent Compositional Analysis of Seven RTV Talc Samples. Analytical Report to R. T. Vanderbilt Company, Inc. 22 November 2000. Submitted to Public Comments Record – C. W. Jameson, National Toxicology Program, 10th ROC Nominations "Talc (containing asbestiform fibers)". 4 December 2000. | |||

| * Nord, G. L, S. W. Axen, R. P. Nolan: Mineralogy and Experimental Animal Studies of Tremolitic Talc. Environmental Sciences Laboratory, Brooklyn College, The City University of New York. Submitted to Public Comments Record – C. W. Jameson, National Toxicology Program, 10th ROC Nominations "Talc (containing asbestiform fibers)". 1 December 2000. | |||

| * {{cite journal|author=Kelse, J. W.|author2=Thompson, C. Sheldon|year=1989|title=The Regulatory and Mineralogical Definitions of Asbestos and Their Impact on Amphibole Dust Analysis|journal=AIHA Journal|volume=50|issue=11|pages=613–622|doi=10.1080/15298668991375245}} | |||

| * Wylie, A.G. (2 June 2000) Report of Investigation. Analytical Report on RTV talc submitted to R. T. Vanderbilt Company, Inc. 13 February 1987 (Submitted to Public Comments Record – C. W. Jameson, National Toxicology Program, 10th ROC Nominations "Talc (containing asbestiform fibers)". | |||

| * Crane, D. (26 November 1986) Letter to Greg Piacitelli (NIOSH) describing the analytical findings of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration regarding R. T. Vanderbilt Talc (In OSHA Docket H-33-d and in Public Comments Record – C. W. Jameson, National Toxicology Program, 10th ROC Nominations – 2 June 2000). | |||

| * Crane, D. (12 June 2000) Background Information Regarding the Analysis of Industrial Talcs. Letter to the Consumer Product Safety Commission from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (Appended to CPSC Staff Report on "Asbestos in Children's Crayons" Aug. 2000). | |||