| Revision as of 18:26, 14 October 2007 edit71.91.220.81 (talk) →Precolumbian Period← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 08:50, 12 January 2025 edit undoErinius (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users3,429 edits →Bibliography: date | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|Uto-Aztecan language of Mexico}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2023}} | |||

| {{Infobox Language | |||

| {{Infobox language | |||

| |name = Nahuatl, Mexicano, Nawatl | |||

| | name = Nahuatl | |||

| |nativename = Nāhuatlahtōlli, Māsēwallahtōlli | |||

| | altname = Aztec, Mexicano | |||

| |familycolor = American | |||

| | nativename = {{lang|nah|Nawatlahtolli}}, {{lang|nah|mexikatlahtolli}},<ref>{{Cite web |title=Mexikatlahtolli/Nawatlahtolli (náhuatl) |url=https://sic.cultura.gob.mx/ficha.php?table=frpintangible&table_id=701 |access-date=2022-06-20 |website=Secretaría de Cultura/Sistema de Información Cultural |language=es}}</ref> {{lang|nah|mexkatl}}, {{lang|nah|mexikanoh}}, {{lang|nah|masewaltlahtol}} | |||

| |region = ''']''' <br> (], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]) | |||

| | states = ] | |||

| |speakers = 1.7 million | |||

| | region = North America, Central America | |||

| |fam1 = ] | |||

| | |

| ethnicity = ] | ||

| | speakers = {{sigfig|1.652|2}} million in Mexico, smaller number of speakers among Nahua immigrant communities in the United States | |||

| |fam3 = General Aztec | |||

| | date = 2020 census | |||

| |agency = | |||

| | ref =<ref> INEGI. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020.</ref> | |||

| |iso2=nah | |||

| | familycolor = Uto-Aztecan | |||

| |lc1=nci|ld1=Classical Nahuatl|ll1=Classical Nahuatl | |||

| | fam1 = ] | |||

| |lc2=nhn|ld2=Central Nahuatl|ll2=Central Nahuatl | |||

| | fam2 = ] | |||

| |lc3=nch|ld3=Central Huasteca Nahuatl|ll3=Central Huasteca Nahuatl | |||

| | fam3 = ] | |||

| |lc4=ncx|ld4=Central Puebla Nahuatl|ll4=Central Puebla Nahuatl | |||

| | dia1 = ] | |||

| |lc5=naz|ld5=Coatepec Nahuatl|ll5=Coatepec Nahuatl | |||

| | dia2 = ] | |||

| |lc6=nln|ld6=Durango Nahuatl|ll6=Mexicanero | |||

| | |

| dia3 = ] | ||

| | dia4 = ] | |||

| |lc8=ngu|ld8=Guerrero Nahuatl|ll8=Guerrero Nahuatl | |||

| | nation = Mexico<ref>{{Cite web |title=General Law of Linguistic Rights of Indigenous Peoples |url=http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/257.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080611011220/http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/257.pdf |archive-date=11 June 2008 |language=es}}</ref> | |||

| |lc9=azz|ld9=Highland Puebla Nahuatl|ll9=Highland Puebla Nahuatl | |||

| | agency = ]<ref>{{Cite web |title=Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas homepage |url=http://www.inali.gob.mx/}}</ref> | |||

| |lc10=nhq|ld10=Huaxcaleca Nahuatl|ll10=Huaxcaleca Nahuatl | |||

| | iso2 = nah | |||

| |lc11=nhk|ld11=Isthmus-Cosoleacaque Nahuatl|ll11=Isthmus-Cosoleacaque Nahuatl | |||

| | iso3 = nhe | |||

| |lc12=nhx|ld12=Isthmus-Mecayapan Nahuatl|ll12=Isthmus-Mecayapan Nahuatl | |||

| | iso3comment = {{ubl|]|{{nwr|See ]}}}} | |||

| |lc13=nhp|ld13=Isthmus-Pajapan Nahuatl|ll13=Isthmus-Pajapan Nahuatl | |||

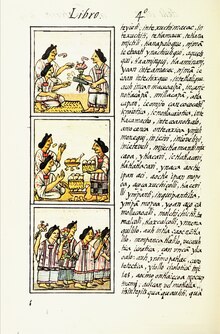

| | image = Historia general de las cosas de nueva España page 406 2.png | |||

| |lc14=ncl|ld14=Michoacán Nahuatl|ll14=Michoacán Nahuatl | |||

| | imagecaption = Nahua man from the '']''. The ]s indicate speech or song. | |||

| |lc15=nhm|ld15=Morelos Nahuatl|ll15=Morelos Nahuatl | |||

| | notice = IPA | |||

| |lc16=nhy|ld16=Northern Oaxaca Nahuatl|ll16=Northern Oaxaca Nahuatl | |||

| | protoname = ] | |||

| |lc17=ncj|ld17=Northern Puebla Nahuatl|ll17=Northern Puebla Nahuatl | |||

| | glotto = azte1234 | |||

| |lc18=nht|ld18=Ometepec Nahuatl|ll18=Ometepec Nahuatl | |||

| | glottoname = Aztec | |||

| |lc19=nlv|ld19=Orizaba Nahuatl|ll19=Orizaba Nahuatl | |||

| | mapscale = 1 | |||

| |lc20=ppl|ld20=Pipil language|ll20=Pipil language | |||

| | map = Nahuatl precontact and modern.svg | |||

| |lc21=nhz|ld21=Santa María la Alta Nahuatl|ll21=Santa María la Alta Nahuatl | |||

| | mapcaption = Current (red) and historical (green) geographic extent of Nahuatl. | |||

| |lc22=nhs|ld22=Southeastern Puebla Nahuatl|ll22=Southeastern Puebla Nahuatl | |||

| | script = {{ubl|]|] {{nwr|(until the 16th century)}}}} | |||

| |lc23=nhc|ld23=Tabasco Nahuatl|ll23=Tabasco Nahuatl | |||

| |lc24=nhv|ld24=Temascaltepec Nahuatl|ll24=Temascaltepec Nahuatl | |||

| |lc25=nhi|ld25=Tenango Nahuatl|ll25=Tenango Nahuatl | |||

| |lc26=nhg|ld26=Tetelcingo Nahuatl |ll26=Tetelcingo Nahuatl | |||

| |lc27=nhj|ld27=Tlalitzlipa Nahuatl|ll27=Tlalitzlipa Nahuatl | |||

| |lc28=nuz|ld28=Tlamacazapa Nahuatl|ll28=Tlamacazapa Nahuatl | |||

| |lc29=nhw|ld29=Western Huasteca Nahuatl |ll29=Western Huasteca Nahuatl | |||

| |lc30=xpo|ld30=Pochutec|ll30=Pochutec | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Nahuatl''' ({{Audio-IPA|nawatl.ogg|}}<ref>This word has several variant spellings, which include: Náhuatl, Naoatl, Nauatl, Nahuatl, Nawatl. In Mexican Spanish the standard spelling is ''náhuatl'' with an accent on the first syllable. (The ''n'' is lower case because Spanish does not capitalize language names.)</ref>) is a group of related languages and dialects of the Aztecan<ref> also called Nahuan.</ref> branch of the ] language family which is indigenous to ] and is spoken by around 1.5 million ] in Central Mexico. | |||

| '''Nahuatl''' ({{IPAc-en|lang|ˈ|n|ɑː|w|ɑː|t|əl}} {{respelling|NAH|wah|təl}};<ref>Laurie Bauer, 2007, ''The Linguistics Student's Handbook'', Edinburgh</ref> {{IPA-nah|ˈnaːwat͡ɬ|-|nawatl.ogg}}),{{refn|group=cn|The ] word {{lang|nah|nāhuatl}} (] {{lang|nah|nāhua}} + ] {{lang|nah|-tl}}) is thought to mean 'a good, clear sound'.{{sfn|Andrews|2003|pages=578,364,398}} This language name has several spellings, among them {{lang|es|náhuatl}} (the standard in Spanish),<ref>{{Cite web |title=Náhuatl |url=http://dle.rae.es/?id=QDH6uCQ |access-date=6 July 2012 |publisher=rae.es |language=es}}</ref> ''Naoatl'', ''Nauatl'', ''Nahuatl'', and ''Nawatl''. In a ] from the name of the language, the ethnic group of Nahuatl speakers are called ''Nahua''.}} '''Aztec''', or '''Mexicano'''<ref>{{Cite web |title=Nahuatl Family |url=https://mexico.sil.org/language_culture/aztec |access-date=2021-02-22 |publisher=SIL Mexico}}</ref> is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the ]. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about {{nowrap|1.7 million}} ], most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller populations ]. | |||

| Groups speaking Nahuan languages have existed in central Mexico at least since 600 AD <ref>Suárez, 1983, p. 149</ref> and at the time of the ] one of these Nahuatl-speaking groups, the ]s dominated central Mexico. Because of the expansion of the Aztec Empire the dialect spoken by the Aztecs of Tenochtitlan had become a prestige language throughout Mesoamerica. With the arrival of the Spanish and the introduction of the ] Nahuatl became also a literary language with large amounts of chronicles, grammars, poetry, administrative documents and codices being written in the language during the 16th and 17th centuries<ref>Canger, 1980, p. 13</ref>. This early literary language based on the Tenochtitlan dialect has been labelled ] and is among the most studied and best documented languages of the ]. | |||

| Nahuatl has been spoken in central Mexico since at least the seventh century CE.<ref name="Suárez 1983:149">{{harvcoltxt|Suárez|1983|page=149}}</ref> It was the language of the ], who dominated what is now central Mexico during the Late Postclassic period of ]. During the centuries preceding the ], the Aztecs had expanded to incorporate a large part of central Mexico. Their influence caused the variety of Nahuatl spoken by the residents of ] to become a ] in Mesoamerica. | |||

| Today ]<ref>See ] for a discussion on the difference between "languages" and "dialects" in Mesoamerica</ref> are spoken by more than 1.5 million people in scattered villages, towns and rural areas<ref></ref>, some of these dialects being mutually unintelligible. All of these dialects show influence from the Spanish language to various degrees, some of them much more than others. No modern dialects are identical with Classical Nahuatl, but those spoken in and around the ] are generally more closely related to it than are peripheral ones.<ref>Canger, 1988</ref>. Under the Mexican "Law of Linguistic Rights" Nahuatl is recognized as a "national language" with the same "validity" as ] and Mexico's other indigenous languages<ref> {es icon}</ref>. | |||

| Following the Spanish conquest, Spanish colonists and missionaries introduced the ], and Nahuatl became a ]. Many ]s, grammars, works of poetry, administrative documents and ] were written in it during the 16th and 17th centuries.{{sfn|Canger|1980|page=13}} This early literary language based on the Tenochtitlan variety has been labeled ]. It is among the most studied and best-documented ].{{sfn|Canger|2002|page=195}} | |||

| Nahuatl is a language with a complex ] characterized by ] and ], allowing the construction of long words with complex meaning out of several stems and ]es. Throughout the centuries of coexistence with the other ] Nahuatl has been influenced by these and has become part of the ]. | |||

| Today, ] are spoken in scattered communities, mostly in rural areas throughout central Mexico and along the coastline. A smaller number of speakers exists in immigrant communities in the United States.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Introduction to Nahuatl |url=https://clas.stanford.edu/outreach/indigenous-language-resources/introduction-nahuatl |access-date=2024-04-02 |website=Center for Latin American Studies}}</ref> There are considerable differences among varieties, and some are not ]. ], with over one million speakers, is the most-spoken variety. All varieties have been subject to varying degrees of ] from Spanish. No modern Nahuan languages are identical to Classical Nahuatl, but those spoken in and around the ] are generally more closely related to it than those on the periphery.{{sfn|Canger|1988}} Under Mexico's '']'', promulgated in 2003,<ref>{{Cite web |date=13 March 2003 |title=Ley General de Derechos Lingüísticos de los Pueblos Indígenas |url=http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/257.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080611011220/http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/257.pdf |archive-date=11 June 2008 |website=Diario Oficial de la Federación |publisher=Issued by the ] |language=es}}.</ref> Nahuatl and the other 63 indigenous ] are recognized as {{lang|es|lenguas nacionales}} ('national languages') in the regions where they are spoken. They are given the same status as Spanish within their respective regions.<ref group="cn">By the provisions of Article IV: {{lang|es|Las lenguas indígenas...y el español son lenguas nacionales...y tienen la misma validez en su territorio, localización y contexto en que se hablen.}} ("The indigenous languages ... and Spanish are national languages ... and have the same validity in their territory, location and context in which they are spoken.")</ref> | |||

| Many words from Nahuatl have been borrowed into Spanish and further on into hundreds of other languages. These are mostly words for concepts indigenous to central Mexico which the Spanish heard mentioned for the first time by their Nahuatl names. English words of Nahuatl origin include "]" from Nahuatl ''tōmatl'', "]" from Nahuatl ''ahuacatl'', and "]" from Nahuatl ''chīlli''. | |||

| Nahuan languages exhibit a complex ], or system of word formation, characterized by ] and ]. This means that morphemes{{snd}}words or fragments of words that each contain their own separate meaning{{snd}}are often strung together to make longer complex words. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ===Precolumbian Period=== | |||

| Archaeological, historical and linguistic evidence suggest that the speakers of Nahuatl languages originally came from the northern Mexican deserts and migrated into central Mexico in several waves.<ref>Canger (1980, p.12)</ref> Before the Nahuan languages entered Mesoamerica they were probably spoken in northwestern Mexico alongside the Coracholan languages(] and ]).<ref>Kaufman (2001, p.12).</ref> The first group to split from the main group were the ] who went on to settle on the Pacific coast of ] possibly as early as 400 AD<ref>Suárez (1983, p.149).</ref> From ca 600 AD Nahuan speakers quickly rose to power in central Mexico and expanded into areas earlier occupied by speakers of ], ] and ].<ref>Kaufman (2001).</ref>. Also some speakers of Nahuan moved south as far as El Salvador and Panama<ref>Fowler (1985, p.38).</ref> becoming the ancestors of the speakers of modern ].<ref>Kaufman (2001).</ref> The earliest migrations are thought to correspond to the modern peripheral dialects some of which are relatively conservative and do not display much influence from the central dialects.<ref>Canger (1988, p.64).</ref> | |||

| Through a very long period of development alongside other indigenous ], they have absorbed many influences, coming to form part of the ]. Many words from Nahuatl were absorbed into Spanish and, from there, were diffused into hundreds of other languages in the region. Most of these loanwords denote things indigenous to central Mexico, which the Spanish heard mentioned for the first time by their Nahuatl names. English has also absorbed words of ], including '']'', '']'', ], '']'', ''chocolate'', {{lang|nah|]}}, '']'', '']'', '']'' and ''tomato''. These words have since been adopted into dozens of languages around the world.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Pint |first=John |date=2022-11-11 |title=The surprising number of Nahuatl words used in modern Mexican Spanish |url=https://mexiconewsdaily.com/mexico-living/nahuatl-words-used-in-everyday-mexico/ |access-date=2024-04-01 |website=Mexico News Daily}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Lesson Nine |url=https://www.babbel.com/en/magazine/indigenous-languages-nahuatl |access-date=2024-04-01 |website=babbel.com}}</ref> The names of several countries, Mexico, ], and ], derive from Nahuatl.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Alex |date=2018-03-23 |title=Etymology of Country Names |url=https://vividmaps.com/etymology-country-names/ |access-date=2024-06-07 |website=Vivid Maps}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Etymology of Nicaragua |url=https://etimologias.dechile.net/?Nicaragua}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Nahuatl Dictionary Letter N |url=https://www.vocabulario.com.mx/nahuatl/diccionario_nahuatl_n.html}}</ref> | |||

| Around 1000 AD Nahuatl speakers were dominant in the Valley of Mexico and far beyond, and migrations kept coming in from the north. One of the last of these migrations to arrive in the valley settled on an island in the ] and proceded to subjugate the surrounding tribes. This group were the ] who during the next 300 years founded an empire based in Tenochtitlan their island capital. Their political and linguistic influence came to reach well into Central America and it is well documented that among several non-Nahuan ethnic groups, such as the ] Maya, Nahuatl became a prestige language used for long distance trade and spoken by the elite groups. | |||

| == Classification == | |||

| ===Colonial Period=== | |||

| {{Main|Nahuan languages}} | |||

| With the arrival of the Spanish in 1519 the tables turned for the Nahuatl language and a new language was now in the prestige position. But the missionary effort undertaken by monks from various monastic orders principally the ]s, ]s and ]s introduced the alphabet to the Nahuas and they were eager to learn to read and write, both in Spanish and in their own language. Within the first ten years after the Spanish arrival texts were being prepared in the Nahuatl language written with Latin characters. | |||

| ] | |||

| As a language label, the term ''Nahuatl'' encompasses a group of closely related languages or divergent dialects within the Nahuan branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family.{{Sfn|Pharao Hansen|2024|p=5–6}} The Mexican {{langr|es|]}} (Indigenous Languages Institute) recognizes 30 individual varieties within the "language group" labeled Nahuatl.{{sfn|INALI|2008|pp=10–37}}<ref>{{cite web |title=Catálogo de las Lenguas Indígenas Nacionales |url=https://www.inali.gob.mx/clin-inali/ |publisher=Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas |access-date=29 December 2024 |language=es}}</ref> The ] recognizes 28 varieties with separate ISO codes.<ref>{{Ethnologue 27 subgroup |family=Nahuatl |number=3952}}</ref> Sometimes Nahuatl is also applied to the ] of El Salvador and Nicaragua. Regardless of whether ''Nahuatl'' is considered to refer to a dialect continuum or a group of separate languages, the varieties form a single branch within the Uto-Aztecan family, descended from a single ]. Within Mexico, the question of whether to consider individual varieties to be languages or dialects of a single language is highly political.{{sfn |Pharao Hansen |2013}} | |||

| In the past, the branch of Uto-Aztecan to which Nahuatl belongs has been called ''Aztecan''. From the 1990s onward, the alternative designation ''Nahuan'' has been frequently used instead, especially in Spanish-language publications. The Nahuan (Aztecan) branch of Uto-Aztecan is widely accepted as having two divisions: General Aztec and Pochutec.<ref>{{harvcoltxt |Canger |1988 |pages=42–43}}, {{harvcoltxt |Dakin |1982 |page=202}}, {{harvcoltxt |INALI |2008 |page=63}}, {{harvcoltxt |Suárez |1983 |page=149}}</ref> | |||

| Also during this time institutions of learning were opened, such as the ] which was inaugurated in 1536 and which taught both indigenous and classical European languages to both Indians and priests. And missionary grammarians undertook the job of writing grammars for the indigenous languages in order to teach priests. For example the first grammar of ], written by ], was published in 1547 - three years before the first grammar of French, and by 1645 another four grammars of Nahuatl had been published: One by ] in 1571, one by Antonio del Rincón in 1595, one by Diego de Guzman in 1642 and the grammar today seen as being the most important by ] in 1645.<ref>Canger, 1980, p.14</ref> | |||

| General Aztec encompasses the Nahuatl and Pipil languages.<ref group="cn">"General Aztec is a generally accepted term referring to the most shallow common stage, reconstructed for all present-day Nahuatl varieties; it does not include the Pochutec dialect {{harvcoltxt |Campbell |Langacker |1978}}." {{harvcoltxt |Canger |2000 |page=385(Note 4)}}</ref> ] is a scantily attested language, which became extinct in the 20th century,{{sfn|Boas|1917}}{{sfn|Knab|1980}} and which Campbell and Langacker classify as being outside general Aztec. Other researchers have argued that Pochutec should be considered a divergent variant of the western periphery.<ref>{{harvcoltxt |Canger |Dakin |1985 |page=360}}, {{harvcoltxt |Dakin |2001 |pages=21–22}}</ref> | |||

| In 1570 ] decreed that Nahuatl should become the official language of the colonies of ] in order to facilitate communication between the Spanish and natives of the colonies. | |||

| ''Nahuatl'' denotes at least Classical Nahuatl, together with related modern languages spoken in Mexico. The inclusion of Pipil in this group is debated among linguists. Lyle {{harvcoltxt|Campbell|1997}} classified Pipil as separate from the Nahuatl branch within general Aztecan, whereas dialectologists such as ], Karen Dakin, ], and Terrence Kaufman have preferred to include Pipil within the General Aztecan branch, citing close historical ties with the eastern peripheral dialects of General Aztec.<ref>{{harvcoltxt |Dakin |2001 |pages=21–22}}, {{harvcoltxt |Kaufman |2001}}</ref> | |||

| During the 16th and 17th centuries Classical Nahuatl was used as a literary language and a large corpus of texts from that period is in existence today. Texts from this period include histories, chronicles, poetry, theatrical works, Christian canonical works, ethnographic description and all kinds of administrative and mundane documents. During this period the Spanish allowed for a great deal of autonomy in the local administration of indigenous towns and in many Nahuatl speaking towns Nahuatl was the de facto administrative language both in writing and speech. Among the most important works from this period is the '']'', a 12-volume compendium of Aztec culture compiled by Franciscan ]; '']'', a chronicle of the royal lineage of Tenochtitlan by ], '']'' a collection of songs in Nahuatl, the Nahuatl-Spanish/Spanish-Nahuatl dictionary compiled by ] and the '']'' a description in Nahuatl of the apparition of the ]. | |||

| Current subclassification of Nahuatl rests on research by {{harvcoltxt|Canger|1980}}, {{harvcoltxt|Canger|1988}} and {{harvcoltxt|Lastra de Suárez|1986}}. Canger introduced the scheme of a Central grouping and two Peripheral groups, and Lastra confirmed this notion, differing in some details. {{harvcoltxt|Canger|Dakin|1985}} demonstrated a basic split between Eastern and Western branches of Nahuan, considered to reflect the oldest division of the proto-Nahuan speech community. Canger originally considered the central dialect area to be an innovative subarea within the Western branch, but in 2011, she suggested that it arose as an urban ] with features from both Western and Eastern dialect areas. {{harvcoltxt|Canger|1988}} tentatively included dialects of ] in the Central group, while {{harvcoltxt|Lastra de Suárez|1986}} places them in the Eastern Periphery, which was followed by {{harvcoltxt|Kaufman|2001}}. | |||

| Throughout the colonial period grammars and dictionaries of indigenous languages were composed, but strangely the quality of these were highest in the initial period and declined towards the ends of the 18th century<ref>Suárez 1983 p5</ref>. In practice the friars found that learning all the indigenous languages was impossible and they began to focus on Nahuatl. During this period the linguistic situation of Mesoamerica was relatively stable. However, in 1696 ] made a counter decree banning the use of any languages other than Spanish throughout the ]. And in 1770 a decree with the avowed purpose of eliminating the indigenous languages was put forth by the Royal Cedula<ref>Suárez 1983 p165</ref>. This marked the end of Nahuatl as a literary language. | |||

| === |

=== Terminology === | ||

| While Nahuatl is the most commonly used name for the language in English, native speakers often refer to the language as {{lang|nah|mexicano}}, or some cognate of the term {{lang|nah|mācēhualli}}, meaning 'commoner'. The word ''Nahuatl'' is derived from the word {{lang|nah|nāhuatlahtōlli}} {{IPA-nah|naːwat͡ɬaʔˈtoːliˀ|}} ('clear language').{{Sfn|Launey|2011|p=xvii}} While it dates to the early colonial period at least, it isn't used by all speakers and is new to many communities.{{Sfn|Pharao Hansen|2024|p=7–8}} Linguists commonly identify localized dialects of Nahuatl by adding as a qualifier the name of the village or area where that variety is spoken. | |||

| Throughout the modern period the situation for indigenous languages have become increasingly worse: Numbers of speakers for virtually all indigenous languages have decreased, and this is also the case for Nahuatl. Nahuatl is now mostly spoken in rural areas by the empoverished class of indigenous subsistence agriculturists. Since the early 20th century educational policies in Mexico have focused on "hispanification" of indigenous communities teaching only Spanish and discouraging the use of Nahuatl. Even so Nahuatl is spoken by well over a million people, most of whom are bilinguals but some of whom are monolingual, and Nahuatl is not as a whole endangered, even though some dialects are severely endangered and others have become extinct within the last ten years. | |||

| The language was formerly called Aztec because it was spoken by the Central Mexican peoples known as ]s ({{IPA-nah|asˈteːkaḁ}}). Now, the term ''Aztec'' is rarely used for modern Nahuan languages, but linguists' traditional name of ''Aztecan'' for the branch of Uto-Aztecan that comprises Nahuatl, Pipil, and Pochutec is still in use (although some linguists prefer ''Nahuan''). Since 1978, the term ''General Aztec'' has been adopted by linguists to refer to the languages of the Aztecan branch excluding the ].{{sfn|Canger|2000|page=385}} | |||

| ==Geographic distribution== | |||

| {{main|List of Nahuan languages}} | |||

| Nahuatl came to be identified with the politically dominant {{lang|nah|mēxihcah}} {{IPA-nah|meːˈʃiʔkaḁ|}} ethnic group, and consequently the Nahuatl language has been called {{lang|nah|mēxihcacopa}} {{IPA-nah|meːʃiʔkaˈkopaˀ|}} (literally 'in the manner of Mexicas'){{Sfn|Pharao Hansen|2024|p=7–8}}{{sfn|Launey|1992|p=116}} or {{lang|nah|mēxihcatlahtolli}} 'Mexica language'. The language is now called ''mexicano'' by many of its native speakers, a term dating to the early colonial period and usually pronounced the Spanish way, with {{IPAblink|h}} or {{IPAblink|x}} rather than {{IPAblink|ʃ}}.{{Sfn|Pharao Hansen|2024|p=7–8}}{{sfn|Hill|Hill|1986|pp=90–93}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Many Nahuatl speakers refer to their language with a cognate derived from {{lang|nah|]}}, the Nahuatl word for 'commoner'.{{Sfn|Pharao Hansen|2024|p=7–8}} One example of that is the Nahuatl spoken in ], Morelos, whose speakers call their language {{lang|es|mösiehuali}}.<ref name="Tuggy 1979:page#">{{harvcoltxt|Tuggy|1979}}</ref> The ] of El Salvador refer to their language as '']''.<ref name="Campbell 1985" /> The Nahuas of ] call their language {{lang|es|Mexicanero}}.{{sfn|Canger|2001}} Speakers of Nahuatl of the ] call their language {{lang|nah|mela'tajtol}} ('the straight language').{{sfn|Wolgemuth|2002}} | |||

| A range of ] are currently spoken in an area stretching from the northern Mexican state of ] to ] in the south. ]<ref>Campbell 1985</ref>, a Nahuatl dialect which happens to have its own name, is spoken as far south as El Salvador, by a small number of speakers<ref>According to the Nawat Language Recuperation Initiative homepage http://www.compapp.dcu.ie/~mward/irin/index.htm numbers maybe be anywhere from 20 to 200 speakers</ref>. Another Nahuan language, ], was spoken on the coast of ] until ] ]<ref>Boas, 1917</ref>. | |||

| == History == | |||

| The largest concentrations of Nahuatl speakers are found in the states of ]<ref>Hill & Hill 1986; Brockaway 1979</ref>, ]<ref>Wolgemuth 2002</ref>, ]<ref>Flores Farfán, 1999</ref> and ]<ref>Beller & Beller, 1979</ref>. Significant populations are also found in ], ]<ref>Tuggy, 1979</ref>, and the ]. Smaller populations exist in ]<ref>Sischo | |||

| {{Main|History of Nahuatl}} | |||

| 1979</ref>, and ]<ref>Canger, 2001</ref>. In ] and ] the language has become extinct during the 20th century. Due to migrations within Mexico nahuatl groups of nahuatl speakers or even small language communities can be found in all of the Mexican states. Currently the influx of Mexican workers into the ] has created small Nahuatl-speaking communities in the United States, particularly in ] and ]<ref>Flores Farfán (2002, p.229).</ref>. | |||

| === Pre-Columbian period === | |||

| On the issue of geographic origin, the consensus of linguists during the 20th century was that the Uto-Aztecan language family originated in the southwestern United States.<ref>{{harvcoltxt|Canger|1980|page=12}}, {{harvcoltxt|Kaufman|2001|page=1}}</ref> Evidence from archaeology and ethnohistory supports the thesis of a southward diffusion across the North American continent, specifically that speakers of early Nahuan languages migrated from ] into central Mexico in several waves. But recently, the traditional assessment has been challenged by ], who proposes instead that the Uto-Aztecan language family originated in central Mexico and spread northwards at a very early date.{{sfn|Hill|2001}} This hypothesis and the analyses of data that it rests upon have received serious criticism.{{sfn|Merrill|Hard|Mabry|Fritz|2010}}{{sfn|Kaufman|Justeson|2009}} | |||

| The proposed migration of speakers of the Proto-Nahuan language into the ] has been placed at sometime around AD 500, towards the end of the Early Classic period in ].{{sfn|Justeson|Norman|Campbell|Kaufman|1985|page=passim}}{{sfn|Kaufman|2001|pages=3–6,12}}{{sfn|Kaufman|Justeson|2007}} Before reaching the ], pre-Nahuan groups probably spent a period of time in contact with the Uto-Aztecan ] and ] of northwestern Mexico.{{sfn|Kaufman|2001|pages=6,12}} | |||

| ==Classification and terminology== | |||

| ===Terminology=== | |||

| The terminology relating to the Nahuatl varieties is rather vague and confusing - many terms are applied with differing meanings, or the some groupings have several names. Sometimes older terms are substituted with newer terms or the speakers own name for their specific variety. | |||

| The major political and cultural center of Mesoamerica in the Early Classic period was ]. The identity of the language(s) spoken by Teotihuacan's founders has long been debated, with the relationship of Nahuatl to Teotihuacan being prominent in that enquiry.<ref>{{harvcoltxt|Cowgill|1992|pages=240–242}}; {{harvcoltxt|Pasztory|1993}}</ref> It was presumed by scholars during the 19th and early 20th centuries that Teotihuacan had been founded by Nahuatl-speakers of, but later linguistic and archaeological research tended to disconfirm this view. Instead, the timing of the Nahuatl influx was seen to coincide more closely with Teotihuacan's fall than its rise, and other candidates such as ] identified as more likely.<ref>{{harvcoltxt|Campbell|1997|page=161}}, {{harvcoltxt|Justeson|Norman|Campbell|Kaufman|1985}}; {{harvcoltxt|Kaufman|2001|pages=3–6,12}}</ref> In the late 20th century, ] evidence has suggested the possibility that other Mesoamerican languages were borrowing vocabulary from Proto-Nahuan much earlier than previously thought.<ref>{{harvcoltxt|Dakin| Wichmann|2000}}, {{harvcoltxt|Macri|2005}}, {{harvcoltxt|Macri|Looper|2003}}, {{harvcoltxt|Cowgill|2003|page=335}}, {{harvcoltxt|Pasztory|1993}}</ref> | |||

| The word Nahuatl itself is a Nahuatl word which is probably derived from the word "''nāwatlahtolli''" - "clear language". The language was formerly called "Aztec" because it was spoken by the Aztecs, who however didn't call themselves Aztecs but Mexica, and who called their language ''Mexicacopa''<ref>Launey, 1992, p. 116</ref>. Nowadays the term "Aztec" is rarely used for modern Nahuan languages, but the term "Aztecan" is used for the Nahuatl languages and dialects when described as the second constituent part of the Uto-Aztecan language family - this group is also often called "Nahuan". The term "General Aztec" is used by some linguists <ref>Canger, 1988 </ref> to refer to the Aztecan languages but not ]. | |||

| In Mesoamerica the ], ] and ] had coexisted for millennia. This had given rise to the ]. After the Nahuas migrated into the Mesoamerican cultural zone, their language likely adopted various areal traits,<ref>{{harvcoltxt|Dakin|1994}}; {{harvcoltxt|Kaufman|2001}}</ref> which included ]s and ]s added to the vocabulary, and a distinctly Mesoamerican grammatical construction for indicating possession. | |||

| The speakers of Nahuatl themselves often refer to their language as "Mexicano"<ref>Hill & Hill, 1986</ref> or a word derived from the Nahuatl word for "commoner" "''mācehualli''"<ref>This is the case for Nahuatl of Tetelcingo, Morelos whose speakers call their language "mösiehuali" (Tuggy 1979) </ref>. The Pipil of El Salvador do not call their own language "Pipil" as most linguists do, but rather "Nawat"<ref>Campbell 1985</ref>. The Nahuas of Durango call their language "Mexicanero"<ref>Canger, 2001</ref>. Speakers of Nahuatl of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec call their language "''mela'tajtol''" - "the straight language". Some speech communities also use the word "Nahuatl" about their language although this seems to be a recent practice. It is common practice for linguists referring to specific dialects of nahuatl to speak of "Nahuatl" adding the village or area where it is spoken as a qualifier, e.g. "Nahuatl of Acaxochitlan". | |||

| A language which was the ancestor of Pochutec split from Proto-Nahuan (or Proto-Aztecan) possibly as early as AD 400, arriving in Mesoamerica a few centuries earlier than the bulk of Nahuan speakers.<ref name="Suárez 1983:149" /> Some Nahuan groups migrated south along the Central American isthmus, reaching as far as Nicaragua. The critically endangered Pipil language of El Salvador is the only living descendant of the variety of Nahuatl once spoken south of present-day Mexico.<ref>{{harvcoltxt|Fowler|1985|page=38}}; {{harvcoltxt|Kaufman|2001}}</ref> | |||

| ===Genealogy=== | |||

| The Nahuatl languages are related to the other ] spoken by peoples such as the ], ], ] and ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and other peoples of western North America. They all belong to the ] linguistic ] which is one of the largest and best studied language families of the Americas consisting of at least 61 individual languages, and spoken from the ] to ]. This is a grouping on the same order as ]. | |||

| During the 7th century, Nahuan speakers rose to power in central Mexico. The people of the ] culture of ], which was active in central Mexico around the 10th century, are thought to have been Nahuatl speakers. By the 11th century, Nahuatl speakers were dominant in the ] and far beyond, with settlements including ], ] and ] rising to prominence. Nahua migrations into the region from the north continued into the ]. The ] were among the latest groups to arrive in the Valley of Mexico; they settled on an island in the ], subjugated the surrounding tribes, and ultimately an empire named ]. Mexica political and linguistic influence ultimately extended into Central America, and Nahuatl became a ] among merchants and elites in Mesoamerica, such as with the Maya ].{{sfn|Carmack|1981|pages=142–143}} As Tenochtitlan grew to become the largest urban center in Central America and one of the largest in the world at the time,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Levy |first=Buddy |title=Conquistador: Hernán Cortés, King Montezuma, and the Last Stand of the Aztecs |publisher=Bantam |year=2008 |isbn=978-0-553-38471-0 |page=106}}</ref> it attracted speakers of Nahuatl from diverse areas giving birth to an urban form of Nahuatl with traits from many dialects. This urbanized variety of Tenochtitlan is what came to be known as Classical Nahuatl as documented in colonial times.{{sfn|Canger|2011}} | |||

| The first linguist to recognize the relationship between the northern ] languages with the southern Aztecan languages was ], and the unity was confirmed in the classification of ] in 1891, the first classification to use the term "Uto-Aztecan" for the language family .<ref>Campbell, 1997, p. 135.</ref> | |||

| === Colonial period === | |||

| The subgroupings of the Nahuan dialects and languages have been the subject of discussions among linguists for the past 50 years. | |||

| With the arrival of the Spanish in 1519, Nahuatl was displaced as the dominant regional language, but remained important in Nahua communities under Spanish rule. Nahuatl was documented extensively during the colonial period in ], Cuernavaca, Culhuacan, Coyoacan, Toluca and other locations in the Valley of Mexico and beyond. In the 1970s, scholars of Mesoamerican ] have analyzed local-level texts in Nahuatl and other indigenous languages to gain insight into cultural change in the colonial era via linguistic changes, known at present as the ].{{sfn|Lockhart|1992}} Several of these texts have been translated and published either in part or in their entirety. The types of documentation include censuses, especially one early set from the Cuernavaca region,{{sfn|Hinz|1983}}{{sfn|Cline|1993}} town council records from Tlaxcala,{{sfn|Lockhart|Berdan|Anderson|1986}} as well as the testimony of Nahua individuals.{{sfn|Cline|León-Portilla|1984}} | |||

| In the early 20th century the first classifications of the Nahuan languages were proposed. Walter Lehmann suggested a basic split between languages which had the /tl/ sound and other which had /t/.<ref>Canger, 1988, p. 31</ref> In 1939 another classification was proposed by ] which distinguished "Nahuat", the dialects with /t/ from "Aztec" the dialects with /tl/. at first the assupmtion of linguists was that /t/ was the original ] and had changed into /tl/ in some dialects only.<ref>Canger, 1988, p. 34</ref> Another classification distinguishing between dialects with /tl/, /t/ and /l/ was proposed by Juan Hasler in the 1950'es but this and the earlier classifications have been criticized by Canger<ref>Canger, 1988</ref> for suffering from methodological flaws and for assuming that the t-tl-l trichotomy reflected an important historical division among the dialects. This assumption however was refuted by ] and ] in 1978 who showed that all the aztecan languages had shared the development of */t/ to /tl/ but that subsequently some dialects had changed the /tl/ back to /t/ or /l/. | |||

| <ref>Campbell & Langacker, 1978, 306</ref> | |||

| As the Spanish had made alliances with Nahuatl-speaking peoples—initially from ], and later the conquered Mexica of Tenochtitlan—Nahuatl continued spreading throughout Mesoamerica in the decades after the conquest. Spanish expeditions with thousands of Nahua soldiers marched north and south to conquer new territories. ] missions in what is now northern Mexico and the southwestern United States often included a '']'' of Tlaxcaltec soldiers who remained to guard the mission.{{sfn|Jackson|2000}} For example, some fourteen years after the northeastern city of ] was founded in 1577, a Tlaxcaltec community was resettled in a separate nearby village, ], to cultivate the land and aid colonization efforts that had stalled in the face of local hostility to the Spanish settlement.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |year=2005 |title=Saltillo, Coahuila |encyclopedia=Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México |publisher=], ] |url=http://www.e-local.gob.mx/work/templates/enciclo/coahuila/mpios/05030a.htm |access-date=2008-03-28 |edition=online version at E-Local |language=es |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070520133556/http://www.e-local.gob.mx/work/templates/enciclo/coahuila/mpios/05030a.htm |archive-date=20 May 2007 |author=INAFED (Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal) |url-status=dead}}. The Tlaxcaltec community remained legally separate until the 19th century.</ref> ] conquered Guatemala with the help of tens of thousands of Tlaxcaltec allies, who then settled outside of modern ].{{sfn|Matthew|2012}} | |||

| The most recent authoritative classifications of the Nahuan languages have been done by ]<ref>Lastra de Suárez, 1986</ref> and by ]<ref>Canger, 1988</ref>. Both classifications are based on dialectological research focusing on the delineation of ]es based on differences in phonology, grammar and vocabulary. The two classifcations are largely identical, but vary on the status of the dialects of ] which Canger places in the central group but are placed by Lastra in a group unto themselves. | |||

| ], featuring Nahuatl written using the Latin alphabet]] | |||

| As a part of their efforts, missionaries belonging to several ]s—principally ], as well as ] and ] friars—introduced the ] to the Nahuas. Within twenty years of the Spanish arrival, texts in Nahuatl were being written using the Latin script.<ref>{{harvcoltxt|Lockhart|1991|page=12}}; {{harvcoltxt|Lockhart|1992|pages=330–331}}</ref> Simultaneously, schools were founded, such as the ] in 1536, which taught both indigenous and classical European languages to both Native Americans and priests. Missionaries authored of ]s for indigenous languages for use by priests. The first Nahuatl grammar, written by ], was published in 1547—3 years before the first grammar in French, and 39 years before the first one in English. By 1645, four more had been published, authored respectively by ] (1571), ] (1595),{{sfn|Rincón|1885}} Diego de Galdo Guzmán (1642), and ] (1645).{{sfn|Carochi|1645}} Carochi's is today considered the most important colonial-era grammar of Nahuatl.{{sfn|Canger|1980|page=14}} Carochi has been particularly important for scholars working in the New Philology, such that there is a 2001 English translation of Carochi's 1645 grammar by ].{{sfn|Carochi|2001}} Through contact with Spanish the Nahuatl language adopted many loan words, and as bilingualism intensified, changes in the grammatical structure of Nahuatl followed.{{sfn|Olko|Sullivan|2013}} | |||

| In 1570, King ] decreed that Nahuatl should become the official language of the colonies of ] to facilitate communication between the Spanish and natives of the colonies.<ref name="Suárez 1983:165">{{harvcoltxt|Suárez|1983|page=165}}</ref> This led to Spanish missionaries teaching Nahuatl to Amerindians living as far south as Honduras and El Salvador. During the 16th and 17th centuries, Classical Nahuatl was used as a literary language; a large corpus dating to the period remains extant. They include histories, chronicles, poetry, theatrical works, Christian canonical works, ethnographic descriptions, and administrative documents. The Spanish permitted a great deal of autonomy in the local administration of indigenous towns during this period, and in many Nahuatl-speaking towns the language was the de facto administrative language both in writing and speech. A large body of ] was composed during this period, including the '']'', a twelve-volume compendium of Aztec culture compiled by Franciscan ]; ''{{lang|es|]}}'', a chronicle of the royal lineage of Tenochtitlan by ]; ''{{lang|es|]}}'', a collection of songs in Nahuatl; a Nahuatl-Spanish/Spanish-Nahuatl dictionary compiled by ]; and the ''{{lang|nah|]}}'', a description in Nahuatl of the apparition of ].{{sfn|Suárez|1983|pages=140–41}} | |||

| The classification below is based on that of Lastra in combination with the classification of Campbell<ref>Campbell, 1997</ref> for the higher level groupings. | |||

| Grammars and dictionaries of indigenous languages were composed throughout the colonial period, but their quality was highest in the initial period.{{sfn|Suárez|1983|page=5}} The friars found that learning all the indigenous languages was impossible in practice, so they concentrated on Nahuatl. For a time, the linguistic situation in Mesoamerica remained relatively stable, but in 1696, ] issued a decree banning the use of any language other than Spanish throughout the ]. In 1770, another decree, calling for the elimination of the indigenous languages, did away with Classical Nahuatl as a literary language.<ref name="Suárez 1983:165" /> Until the end of the ] in 1821, the Spanish courts admitted Nahuatl testimony and documentation as evidence in lawsuits, with court translators rendering it in Spanish.{{sfn|Cline|Adams|MacLeod|2000}} | |||

| *Uto-Aztecan ''5000 BP''<sup>*</sup> | |||

| **Shoshonean (Northern Uto-Aztecan) | |||

| **Sonoran<sup>**</sup> | |||

| **Aztecan ''2000 BP'' (a.k.a. Nahuan) | |||

| ***Pochutec — ''Coast of Oaxaca'' | |||

| *** General Aztec (Nahuatl) | |||

| ****Western periphery | |||

| ****Eastern Periphery | |||

| ****Huasteca | |||

| ****Center | |||

| === 20th and 21st centuries === | |||

| See the ] page for further discussion of the sub-categories of General Aztec, which are somewhat controversial. | |||

| Throughout the modern period the situation of indigenous languages has grown increasingly precarious in Mexico, and the numbers of speakers of virtually all indigenous languages have dwindled. While the total number of Nahuatl speakers increased over the 20th century, indigenous populations have become increasingly marginalized in Mexican society. In 1895, Nahuatl was spoken by over 5% of the population. By 2000, this figure had fallen to 1.49%. Given the process of marginalization combined with the trend of migration to urban areas and to the United States, some linguists are warning of impending ].{{sfn|Rolstad|2002|page=''passim.''}} At present Nahuatl is mostly spoken in rural areas by an impoverished class of indigenous subsistence agriculturists. According to the Mexican ] (INEGI), as of 2005 51% of Nahuatl speakers are involved in the farming sector and 6 in 10 Nahuatl-speakers who work receive no wages or less than the minimum wage.{{sfn|INEGI|2005|pages=63–73}} | |||

| For most of the 20th century, Mexican educational policy focused on the ] of indigenous communities, teaching only Spanish and discouraging the use of indigenous languages.{{sfn|Suárez|1983|page=167}} As a result, one scholar estimated in 1983 that there was no group of Nahuatl speakers who had attained general literacy (that is, the ability to read the classical language) in Nahuatl,{{sfn|Suárez|1983|page=168}} and Nahuatl speakers' literacy rate in Spanish also remained much lower than the national average.{{sfn|INEGI|2005|page=49}} Nahuatl is spoken by over 1 million people, with approximately 10% of speakers being ]. As a whole, Nahuatl is not considered to be an endangered language; however, during the late 20th century several Nahuatl dialects became extinct.<ref>{{harvcoltxt|Lastra de Suárez|1986}}, {{harvcoltxt|Rolstad|2002|page=passim}}</ref> | |||

| <small> | |||

| :<sup>*</sup>Estimated split date by ] ''(BP = Before the Present).'' | |||

| :<sup>**</sup>Some scholars continue to classify Aztecan and Sonoran together under a separate group (called variously "Sonoran", "Mexican", or "Southern Uto-Aztecan"). There is increasing evidence that whatever degree of additional resemblance there might be between Aztecan and Sonoran when compared with Shoshonean is probably due to proximity contact, rather than to a common immediate parent stock other than Uto-Aztecan. | |||

| </small> | |||

| The 1990s saw radical changes in Mexican policy concerning indigenous and linguistic rights. Developments of accords in the international rights arena<ref group="cn">Such as the 1996 adoption at a world linguistics conference in Barcelona of the ], a declaration which "became a general reference point for the evolution and discussion of linguistic rights in Mexico" {{harvcoltxt|Pellicer|Cifuentes|Herrera|2006|page=132}}</ref> combined with domestic pressures (such as social and political agitation by the ] and indigenous social movements) led to legislative reforms and the creation of decentralized government agencies like the ] (CDI) and the ] (INALI) with responsibilities for the promotion and protection of indigenous communities and languages.{{sfn|Pellicer|Cifuentes|Herrera|2006|pages=132–137}} | |||

| ==Phonology of Nahuan languages== | |||

| ===Historical phonological changes=== | |||

| The Nahuan subgroup of Uto-Aztecan is classified partly by a number of shared phonological changes from reconstructed Proto-Uto-Aztecan to the attested Nahuan languages. The changes shared between the Nahuan languages are the basis for the reconstruction of the intermediate stage of Proto-Nahuan. Some of these changes shared by all Nahuan languages are: | |||

| In particular, the federal '']'' recognizes all the country's indigenous languages, including Nahuatl, as ]s and gives indigenous people the right to use them in all spheres of public and private life. In Article 11, it grants access to compulsory ].<ref>{{Cite web |year=n.d. |title=Presentación de la Ley General de Derechos Lingüísticos |url=http://www.inali.gob.mx/ind-leyes.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080317120048/http://www.inali.gob.mx/ind-leyes.html |archive-date=17 March 2008 |access-date=2008-03-31 |website=Difusión de INALI |publisher=Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas, ] |language=es}}</ref> Nonetheless, progress towards institutionalizing Nahuatl and securing linguistic rights for its speakers has been slow.{{sfn|Olko|Sullivan|2013}} | |||

| *Proto-Uto-Aztecan *t becomes Proto-Nahuan lateral affricate *tl before Proto-Uto-Aztecan *a | |||

| *Proto-Uto-Aztecan initial *p is lost in Proto-Nahuan. | |||

| *Proto-Uto-Aztecan *u merges with *i into Proto-Nahuan *i | |||

| *Proto-Uto-Aztecan sibilants *ts and *s split into *ts, *ch and *s, *{{IPA|ʃ}} respectively. | |||

| *Proto-Uto-Aztecan fifth vowel reconstructed as *{{IPA|ɨ}} or *{{IPA|ə}} merged with *e into Proto-Nahuan *e | |||

| *a large number of metatheses in which Proto-Uto-Aztecan roots of the shape *CVCV have become *VCCV. | |||

| == Demography and distribution == | |||

| The table below presents some of the changes that are reconstructed from Proto-Uto-Aztecan to Proto-Nahuan. | |||

| {{Main|Nahuan languages|Nahua peoples}} | |||

| {| class="wikitable sortable" style="float:right; margin:0 0 0.5em 1em;" | |||

| Table of reconstructed changes from Proto-Uto-Aztecan to Proto-Nahuan | |||

| |- | |||

| {| border="1" cellpadding="4" cellspacing="0" style="margin: 0.5em 1em 0.5em 0; background: #f9f9f9; border: 1px #aaa solid; border-collapse: collapse;" | |||

| |+ Nahuatl speakers over 5 years of age in the ten states with most speakers (]). Absolute and relative numbers. Percentages given are in comparison to the total population of the corresponding state. {{harvcoltxt|INEGI|2005|page=4}} | |||

| | colspan="1" |''' PUA '''||''' Proto-Nahuan''' | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="col" | Region | |||

| ! scope="col" | Totals | |||

| ! scope="col" | Percentages | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| | style="text-align:right" | 37,450 | |||

| | style="text-align:right" | 0.44% | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|136,681 | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|4.44% | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|221,684 | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|9.92% | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|55,802 | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|0.43% | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|18,656 | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|1.20% | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|10,979 | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|0.32% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| | rowspan="1" | *ta:ka ''"man"''||*tla:ka-tla ''"man" '' | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|416,968 | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|8.21% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| | rowspan="1" | *pahi ''"water"''|| *a:-tla ''"water"'' | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|138,523 | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|6.02% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| | rowspan="1" | *muki ''"to die"''|| *miki ''"to die'' | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|23,737 | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|2.47% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| | rowspan="1" | *pu:li ''"to tie"''|| *ilpi ''"to tie" '' | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|338,324 | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|4.90% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" | Rest of Mexico | |||

| | rowspan="1" | *n{{IPA|ɨ}}mi ''"to walk"''|| *nemi ''"to live, to walk"'' | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|50,132 | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|0.10% | |||

| |- class="sortbottom" style="background-color:#F2F2F2;" | |||

| ! scope="row" | Total | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|1,448,937 | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|1.49% | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| ] | |||

| Today, a spectrum of ] are spoken in scattered areas stretching from the northern state of ] to ] in the southeast. Pipil,<ref name="Campbell 1985">{{harvcoltxt|Campbell|1985}}</ref> the southernmost Nahuan language, is spoken in El Salvador by a small number of speakers. According to IRIN-International, the Nawat Language Recovery Initiative project, there are no reliable figures for the contemporary numbers of speakers of Pipil. Numbers may range anywhere from "perhaps a few hundred people, perhaps only a few dozen".{{sfn|IRIN|2004}} | |||

| According to the 2000 census by INEGI, Nahuatl is spoken by an estimated 1.45 million people, some 198,000 (14.9%) of whom are monolingual.{{sfn|INEGI|2005|page=35}} There are many more female than male monolinguals, and women represent nearly two-thirds of the total number. The states of Guerrero and Hidalgo have the highest rates of monolingual Nahuatl speakers relative to the total Nahuatl speaking population, at 24.2% and 22.6%, respectively. For most other states the percentage of monolinguals among the speakers is less than 5%. This means that in most states more than 95% of the Nahuatl speaking population are bilingual in Spanish.{{sfn|INEGI|2005}} According to one study, how often Nahuatl is used is linked to community well-being, partly because it is tied to positive emotions.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Olko |first1=Justyna |last2=Lubiewska |first2=Katarzyna |last3=Maryniak |first3=Joanna |last4=Haimovich |first4=Gregory |last5=de la Cruz |first5=Eduardo |last6=Cuahutle Bautista |first6=Beatriz |last7=Dexter-Sobkowiak |first7=Elwira |last8=Iglesias Tepec |first8=Humberto |year=2022 |orig-date=2021 |title=The positive relationship between Indigenous language use and community-based well-being in four Nahua ethnic groups in Mexico |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34672647/ |journal=Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology |volume=28 |issue=1 |pages=132–143 |doi=10.1037/cdp0000479 |issn=1099-9809 |pmid=34672647}}</ref> | |||

| From the changes common to all Nahuan languages the subgroup has diversified somewhat and giving a complete overview of the phonologies of Nahuan languages is not suitable here. However, the table below shows a standardised phonemic inventory based on the inventory of Classical Nahuatl. Many modern dialects have undergone changes from proto-Nahuan that have resulted in different phonemic inventories. | |||

| The largest concentrations of Nahuatl speakers are found in the states of ], ], ], ], and ]. Significant populations are also found in the ], ], and the ], with smaller communities in ] and ]. Nahuatl became extinct in the states of ] and ] during the 20th century. As a result of internal migration within the country, Nahuatl speaking communities exist in all states in Mexico. The modern influx of Mexican workers and families into the United States has resulted in the establishment of small ], particularly in California, New York, ], ] and ].{{sfn|Flores Farfán|2002|page=229}} | |||

| ===Consonants=== | |||

| Table of Nahuatl consonants | |||

| == Phonology == | |||

| {| border="1" cellpadding="4" cellspacing="0" style="margin: 0.5em 1em 0.5em 0; background: #f9f9f9; border: 1px #aaa solid; border-collapse: collapse;" | |||

| Nahuan languages are defined as a subgroup of Uto-Aztecan by having undergone a number of shared changes from the ] (PUA). The table below shows the ] inventory of Classical Nahuatl as an example of a typical Nahuan language. In some dialects, the {{IPA|/t͡ɬ/}} phoneme, which was common in Classical Nahuatl, has changed into either {{IPA|/t/}}, as in ], ] and ], or into {{IPA|/l/}}, as in ].{{sfn|Sischo|1979|page=''passim''}} Many dialects no longer distinguish between short and long ]s. Some have introduced completely new vowel qualities to compensate, as is the case for ].<ref name="Tuggy 1979:page#" /> Others have developed a ], such as Nahuatl of Oapan, ].{{sfn|Amith|1989}} Many modern dialects have also borrowed phonemes from Spanish, such as {{IPA|/β, d, ɡ, ɸ/}}.<ref name="Flores Farfán 1999">{{harvcoltxt|Flores Farfán|1999}}</ref> | |||

| | colspan="1" | || ] || ] || ] || ] || ] | |||

| === Phonemes === | |||

| {{col-begin}} | |||

| {{col-2}} | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center" | |||

| |+ Classical Nahuatl consonants | |||

| ! rowspan=2 | | |||

| ! rowspan=2 scope="col" |] | |||

| ! colspan=2 scope="col" |] | |||

| ! rowspan=2 scope="col" |] | |||

| ! colspan=2 scope="col" |] | |||

| ! rowspan=2 scope="col" |] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| | rowspan="1" | ]|| {{IPA|p}} || {{IPA|t}} || || k / {{IPA|kʷ}} || {{IPA|ʔ}} ({{IPA|h}}) | |||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| ! scope="row" | plain | |||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| | rowspan="1" | ] || || {{IPA|s}}|| {{IPA|ʃ}} || || | |||

| | {{IPA link|m}}||{{IPA link|n}}|| || || || || | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| | rowspan="1" | ] || || {{IPA|tɬ}} / ts || {{IPA|tʃ}} || || | |||

| | {{IPA link|p}}||{{IPA link|t}}|| || ||{{IPA link|k}}||{{IPA link|kʷ}}||{{IPA link|ʔ}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| | rowspan="1" | ] || {{IPA|w}} || {{IPA|l}} || {{IPA|j}} || || | |||

| | ||{{IPA link|ts}}||{{IPA link|tɬ}}||{{IPA link|tʃ}}|| || || | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| | rowspan="1" | ]|| {{IPA|m}} || {{IPA|n}} || || || | |||

| | ||{{IPA link|s}}||{{IPA link|l}}||{{IPA link|ʃ}}|| || ||({{IPA link|h}})* | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| | || || ||{{IPA link|j}}|| ||{{IPA link|w}}|| | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| {|class=wikitable style="text-align: center" | |||

| ===Vowels=== | |||

| |+Classical Nahuatl vowels | |||

| ! rowspan=2| | |||

| {| border="1" cellpadding="4" cellspacing="0" style="margin: 0.5em 1em 0.5em 0; background: #f9f9f9; border: 1px #aaa solid; border-collapse: collapse;" | |||

| ! colspan=2|] | |||

| | colspan="1" | || colspan="2" | front || colspan="2" | central || colspan="2" | back | |||

| ! colspan=2|] | |||

| ! colspan=2|] | |||

| |- class=small | |||

| !long||short||long||short||long||short | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| !] | |||

| | colspan="1" | || long || short || long || short || long || short | |||

| |{{IPA link|iː}}||{{IPA link|i}}|| || ||rowspan="2"|{{IPA link|oː}}~{{IPA link|uː}}||rowspan="2"|{{IPA link|o}}~{{IPA link|u}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! ] | |||

| | rowspan="1" | high ||{{IPA|iː}}||{{IPA|i}}|| || || || | |||

| |{{IPA link|eː}}||{{IPA link|e}}|| || | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! ] | |||

| | || ||{{IPA link|aː}}||{{IPA link|a}}|| || | |||

| |} | |||

| {{col-end}} | |||

| *<nowiki>*</nowiki> The glottal phoneme, called the '']'', occurs only after vowels. In many modern dialects it is realized as a {{IPA|}}, but in others, as in Classical Nahuatl, it is a glottal stop {{IPA|}}.{{sfn|Pury-Toumi|1980}} | |||

| In many Nahuatl dialects vowel length contrast is vague, and in others it has become lost entirely. The dialect spoken in Tetelcingo (nhg) developed the vowel length into a difference in quality:<ref>Pittman, R. S. (1961). . In B. F. Elson & J. Comas (Eds.), ''A William Cameron Townsend en el vigésimoquinto aniversario del Instituto Lingüístico de Verano'' (pp. 643–651). Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.</ref> | |||

| | rowspan="1" | mid || {{IPA|eː}}|| {{IPA|e}} || || ||{{IPA|oː}}||{{IPA|o}} | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| ! | |||

| ! colspan="4" scope="colgroup" | Long vowels | |||

| ! colspan="4" scope="colgroup" | Short vowels | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" | Classical Nahuatl | |||

| | rowspan="1" | low || || ||{{IPA|aː}} ||{{IPA|a}} || || | |||

| |{{IPA|/iː/}} | |||

| |{{IPA|/eː/}} | |||

| |{{IPA|/aː/}} | |||

| |{{IPA|/oː/}} | |||

| |{{IPA|/i/}} | |||

| |{{IPA|/e/}} | |||

| |{{IPA|/a/}} | |||

| |{{IPA|/o/}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" | Tetelcingo dialect | |||

| |{{IPA|/i/}} | |||

| |{{IPA|/i̯e/}} | |||

| |{{IPA|/ɔ/}} | |||

| |{{IPA|/u/}} | |||

| |{{IPA|/ɪ/}} | |||

| |{{IPA|/e/}} | |||

| |{{IPA|/a/}} | |||

| |{{IPA|/o/}} | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| == |

=== Allophony === | ||

| Most varieties have relatively simple patterns of ]. In many dialects, the voiced consonants are devoiced in word-final position and in consonant clusters: {{IPA|/j/}} devoices to a ] {{IPA|/ʃ/}},{{sfn|Launey|1992|p=16}} {{IPA|/w/}} devoices to a ] {{IPA|}} or to a ] {{IPA|}}, and {{IPA|/l/}} devoices to a ] {{IPA|}}. In some dialects, the first consonant in almost any consonant cluster becomes {{IPA|}}. Some dialects have productive ] of ] into their voiced counterparts between vowels. The ] are normally ] to the place of articulation of a following consonant. The ] {{IPA|}} is assimilated after {{IPA|/l/}} and pronounced {{IPA|}}.{{sfn|Launey|1992|page=26}} | |||

| {{main|Classical Nahuatl grammar}} | |||

| === Phonotactics === | |||

| The Nahuatl languages are ], ] languages that make extensive use of compounding, incorporation and derivation. That is, they can add many different ]es and ]es to a root until very long words are formed. Very long verbal forms or nouns created through incorporation and accumulation of prefixes are not uncommon in literary works. This also means that new words can be created at a moment's notice. | |||

| Classical Nahuatl and most of the modern varieties have fairly simple phonological systems. They allow only syllables with maximally one initial and one final consonant.<ref>{{Harvnb|Aguilar|2013}}, citing {{Harvnb|Andrews|2003}}, {{Harvnb|Bedell|2011}}, {{Harvnb|Brockway|1963}}, and {{Harvnb|Goller|Goller|Waterhouse|1974}}</ref> | |||

| Consonant clusters occur only word-medially and over syllable boundaries. Some ]s have two alternating forms: one with a vowel ''i'' to prevent consonant clusters and one without it. For example, the absolutive ] has the variant forms ''-tli'' (used after consonants) and ''-tl'' (used after vowels).{{sfn|Launey|1992|pages=19–22}} Some modern varieties, however, have formed complex clusters from vowel loss. Others have contracted syllable sequences, causing accents to shift or vowels to become long.<ref group="cn">{{harvcoltxt|Sischo|1979|page=312}} and {{harvcoltxt|Canger|2000}} for a brief description of these phenomena in Michoacán and Durango Nahuatl, respectively.</ref> | |||

| === Stress === | |||

| A minority of linguists consider the ] of Nahuatl to be ]. This was first proposed by ] in the early ]. However, by the mid-], this view was largely dismissed by the linguistic community. | |||

| Most Nahuatl dialects have stress on the penultimate syllable of a word. In Mexicanero from Durango, many unstressed syllables have disappeared from words, and the placement of syllable stress has become phonemic.{{sfn|Canger|2001|page=29}} | |||

| == Morphology and syntax == | |||

| ==Vocabulary== | |||

| {{further|Classical Nahuatl grammar}} | |||

| {{wiktionarycat|type=of the Nahuatl language|category=Nahuatl language}} | |||

| {{wiktionarycat|type=of Nahuatl origin|category=Nahuatl derivations}} | |||

| The Nahuatl languages are ] and ], making extensive use of compounding, incorporation and derivation. Various prefixes and suffixes can be added to a ] to form very long words—individual Nahuatl words can constitute an entire sentence..{{sfn|Launey|1999}} | |||

| ] ]s on a ] ]] | |||

| ===Loanwords from Nahuatl in other languages=== | |||

| {{main|words of Nahuatl origin}} | |||

| Many Nahuatl words have been borrowed into the ], many of which are terms designating things indigenous to the American continent. Some of these loans are restricted to Mexican or Central American Spanish, but others have entered all the varieties of Spanish in the world and a number of them, such as "chocolate", "tomato" and "avocado" have made their way into many other languages via Spanish. For example, because of extensive ] during Spanish colonialism in both regions, there are an estimated 250 words of Nahuatl origin in the ]. | |||

| Likewise a number of English words have been borrowed from Nahuatl through Spanish. Two of the most prominent are undoubtedly ] (from ''xocolātl'', 'chocolate drink', perhaps literally 'bitter-water') and ] (from ''(xi) tomatl''). But there are others, such as ] (''coyotl''), ] (''ahuacatl'') and ] (''chilli''). The brand name ] is also derived from Nahuatl (''tzictli'' 'sticky stuff, chicle'). Other English words from Náhuatl are: ], (''aztecatl''); ] (''cacahuatl'' 'shell, rind'); ] (''mizquitl''); ] (''ocelotl''); ] (''xacalli''), and more. | |||

| The following ] shows how the verb is marked for ], ], ], and indirect object: | |||

| Many well-known toponyms also come from Nahuatl, including ''Mexico'' (''mexihco'') and ''Guatemala'' (''cuauhtēmallan''). | |||

| {{interlinear|indent=3 | |||

| In Mexico many words for common everyday concepts attest to the close contact between Spanish and Nahuatl: | |||

| |ni- mits- teː- tla- makiː -lti -s | |||

| |I- you- someone- something- give -CAUS -FUT | |||

| |"I shall make somebody give something to you"<ref group="cn">All examples given in this section and these subsections are from {{harvcoltxt|Suárez|1983|pages=61–63}} unless otherwise noted. Glosses have been standardized.</ref> (Classical Nahuatl)}} | |||

| === Nouns === | |||

| :''achiote, aguacate, ajolote, amate, atole, axolotl, ayate, cacahuate, camote, capulín, chapopote, chayote, chicle, chile, chipotle, chocolate, cuate, comal, copal, coyote, ejote, elote, epazote, escuincle, guacamole, guajolote, huipil, huitlacoche, hule, jícama, jícara, jitomate, malacate, mecate, metate, metlapil, mezcal, mezquite, milpa, mitote, molcajete, mole, nopal, ocelote, ocote, olote, paliacate, papalote, pepenar, petate, peyote, pinole, popote, pozole, quetzal, tamal, tianguis, tlacuache, tomate, zacate, zapote, zopilote.'' | |||

| The Nahuatl noun has a relatively complex structure. The only obligatory inflections are for ] (singular and plural) and possession (whether the noun is possessed, as is indicated by a prefix meaning 'my', 'your', etc.). Nahuatl has neither ] nor ], but Classical Nahuatl and some modern dialects distinguish between ] and inanimate nouns. In Classical Nahuatl the animacy distinction manifested with respect to pluralization, as only animate nouns could take a plural form, and all inanimate nouns were uncountable (as the words ''bread'' and ''money'' are uncountable in English). Now, many speakers do not maintain this distinction and all nouns may take the plural inflection.{{sfn|Hill|Hill|1980}} One dialect, that of the Eastern Huasteca, has a distinction between two different plural suffixes for animate and inanimate nouns.{{sfn|Kimball|1990}} | |||

| In most varieties of Nahuatl, nouns in the unpossessed singular form generally take an absolutive suffix. The most common forms of the absolutive are ''-tl'' after vowels, ''-tli'' after consonants other than ''l'', and ''-li'' after ''l''. Nouns that take the plural usually form the plural by adding one of the plural absolutive suffixes -''tin'' or -''meh'', but some plural forms are irregular or formed by ]. Some nouns have competing plural forms.{{sfn|Launey|1992|pages=27–28}} | |||

| (The persistent ''-te'' or ''-le'' endings on these words are Spanish reflexes of the Nahuatl 'absolutive' ending ''-tl'', ''-tli'', or ''-li'', which appears on (most) nouns when they are not possessed or in the plural.) | |||

| {{col-begin}} | |||

| ==Writing systems== | |||

| {{col-3}} | |||

| At the time of the Spanish conquest, Aztec writing used mostly ]s supplemented by a few ]s. When needed, it also used syllabic equivalences; Father ] recorded how the ''tlahcuilos'' (codex painters) could render a prayer in Latin using this system, but it was difficult to use as it was still in development. This writing system was adequate for keeping such records as genealogies, astronomical information, and tribute lists, but could not represent a full vocabulary of spoken language in the way that the writing systems of the old world or of the ] could. The Aztec writing was not meant to be read, but to be told; the elaborate codices were essentially pictographic aids for teaching, and long texts were memorized. | |||

| Singular noun: | |||

| {{interlinear|indent=3|kojo -tl|coyote -ABS|"coyote" (Classical Nahuatl)}} | |||

| {{col-2}} | |||

| Plural animate noun: | |||

| {{interlinear|indent=3|kojo -meʔ|coyote -PL|"coyotes" (Classical Nahuatl)}} | |||

| {{col-end}} | |||

| Plural animate noun with reduplication: | |||

| The Spanish introduced the Roman script, which was then utilized to record a large body of Aztec prose and poetry, a fact which somewhat mitigated the devastating loss of the thousands of Aztec manuscripts which were burned by the Spanish. Important lexical works (e.g. ]'s classic ''Vocabulario'' of 1571) and grammatical descriptions (of which ]'s 1645 ''Arte'' is generally acknowledged the best) were produced using variations of this ]. | |||

| {{interlinear|indent=3|/koː~kojo-ʔ/|PL~coyote-PL|"coyotes" (Classical Nahuatl)}} | |||

| Carochi's ortography used two different accents: a ] to represent long vowels and a ] for the ''saltillo''. | |||

| Nahuatl distinguishes between possessed and unpossessed forms of nouns. The absolutive suffix is not used on possessed nouns. In all dialects, possessed nouns take a prefix agreeing with number and person of its possessor. Possessed plural nouns take the ending ''-{{IPA|/waːn/}}''.{{sfn|Launey|1992|pages=88–89}} | |||

| The classic orthography is not perfect, and in fact there were many variations in how it is applied, due in part to dialectal differences and in part to differing traditions and preferences that developed. (The writing of Spanish itself was far from totally standardized at the time.) Today, although almost all written Nahuatl uses some form of Latin-based orthography, there continue to be strong dialectal differences, and considerable debate and differing practices regarding how to write sounds even when they are the same. Major issues are | |||

| *whether to follow Spanish in writing the {{IPA|/k/}} sound sometimes as ''c'' and sometimes as ''qu'' or just to use ''k'' | |||

| *how to write {{IPA|/kʷ/}} | |||

| *what to do about {{IPA|/w/}}, the realization of which varies considerably from place to place and even within a single dialect | |||

| *how to write the "saltillo", phonetically a ] ({{IPA|}}) or an {{IPA|}}, which has been spelled with ''j'', ''h'', and a straight apostrophe ('), but which traditionally was often omitted in writing. | |||

| There are a number of other issues as well, such as | |||

| *whether and how to represent vowel length | |||

| *how and whether to represent sound variants (allophones) which sound like different Spanish sounds , especially variants of ''o'' which come close to ''u'' | |||

| *to what extent writing in one variant should be adapted towards what is used in other variants. | |||

| {{col-begin}} | |||

| The '']'' (Ministry of Public Education) has adopted an alphabet for its bilingual education programs in rural communities in ] in which ''k'' is used and {{IPA|/w/}} is written as ''u'', and this decision has been controversial; SEP's modern ortography does not recognise ''saltillo'' nor long vowels so many people still prefer the classical ortography. The recently established (2004) "]" (]) will also be involved in these issues. | |||

| {{col-2}} | |||

| :''For the pictographic writing system used by the precolumbian Nahua peoples see also'' ] and ] | |||

| Absolutive noun: | |||

| :''For more detail about the different orthographies used to transliterate Nahuatl in the Latin script see ] | |||

| {{interlinear|indent=3|kal -li|house -ABS|"house" (Classical Nahuatl)}} | |||

| {{col-2}} | |||

| Possessed noun: | |||

| {{interlinear|indent=3|no- kal|my- house|"my house" (Classical Nahuatl)}} | |||

| {{col-end}} | |||

| Possessed plural: | |||

| The has adopted a classical Carochi-based writing system, including the use of long accents (macrons) for represent long vowels /ā/, /ē/, /ī/ and /ō/. | |||

| {{interlinear|indent=3|no- kal -waːn|my- house -PL|"my houses" (Classical Nahuatl)}} | |||

| The 25-letter alphabet is: | |||

| <big><center>'''a c ch cu e hu i l* m n o p qu t tl tz x y z ā ē ī ō ll* h*'''</center></big> | |||

| Notes:¨ | |||

| *"cu" and "hu" are inverted to "uc" and "uh" when occuring at the end of a syllable. | |||

| *These (*) letters have not capital form except in foreign names. | |||

| *"h" is used as saltillo. | |||

| Nahuatl does not have ] but uses what is sometimes called a ] to describe spatial (and other) relations. These ]s cannot appear alone but must occur after a noun or a possessive prefix. They are also often called ]s<ref>{{harvcoltxt|Hill|Hill|1986}} re Malinche Nahuatl</ref> or locative suffixes.<ref>{{harvcoltxt|Launey|1992}} Chapter 13 re classical Nahuatl</ref> In some ways these locative constructions resemble and can be thought of as locative case constructions. Most modern dialects have incorporated ] from Spanish that are competing with or that have completely replaced relational nouns.{{sfn|Suárez|1977|pages=''passim''}} | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{ |

{{col-begin}} | ||

| {{col-2}} | |||

| Uses of relational noun/postposition/locative ''-pan'' with a possessive prefix: | |||

| ==Bibliography== | |||

| {{interlinear|indent=3|no-pan|my-in/on|"in/on me" (Classical Nahuatl)}} | |||

| {{ref indent}} <!--Begin hanging indent style --> | |||

| {{interlinear|indent=3|iː-pan|its-in/on|"in/on it" (Classical Nahuatl)}} | |||

| {{refbegin}} <!--Begin refs-small style --> | |||

| {{interlinear|indent=3|iː-pan kal-li|its-in house-ABS|"in the house" (Classical Nahuatl)}} | |||

| : {{cite book |author={{aut|Beller, Richard}} |coauthors=and {{aut|Patricia Beller}} |year=1979 |chapter=Huasteca Nahuatl |editor=Ronald W. Langacker (ed.) |title=Studies in Uto-Aztecan Grammar 2: Modern Aztec Grammatical Sketches |pages=pp.199–306 |series=Summer Institute of Linguistics Publications in Linguistics, 56 |location=Dallas, TX |publisher=] and the University of Texas at Arlington |isbn=0883120720 |oclc=6086368}} | |||

| : {{cite journal |author={{aut|Boas, Franz}} |authorlink=Franz Boas |year=1917 |title=El dialecto mexicano de Pochutla, Oaxaca |journal=] |volume=1 |issue=1|pages=pp.9–44 |location=Chicago |publisher=University of Chicago Press|issn=0020-7071 |oclc=56221629}} {{es icon}} | |||

| : {{cite book |author={{aut|Campbell, Lyle}} |authorlink=Lyle Campbell |year=1985 |title=The Pipil Language of El Salvador |series=Mouton Grammar Library (No. 1) |location=Berlin |publisher=Mouton Publishers |isbn=0-89925-040-8 |oclc=13433705}} | |||

| : {{Cite book |author={{aut|Campbell, Lyle}} |authorlink=Lyle Campbell |year=1997 |title=American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America (Oxford Studies in Anthropological Linguistics, 4) |publisher=Oxford University Press|location= New York |isbn=0-195-09427-1}} | |||

| : {{cite journal |author={{aut|Campbell, Lyle}} |authorlink=Lyle Campbell |coauthors=and {{aut|]}} |title=Proto-Aztecan vowels: Parts I-III.|year=1978 |journal=]|volume=44 |issue= |pages=pp.85–102, 197–210, 262–79|location=Chicago |publisher=University of Chicago Press|issn=0020-7071}} | |||

| : {{cite book |author={{aut|Carochi, Horacio}} |authorlink=Horacio Carochi |year=1983 |origyear=1645 |title=Arte de la lengua mexicana: con la declaración de los adverbios della |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=lIACAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA1&dq=adverbios+della |format=Reprint |location=México D.F. |publisher=Porrúa}} {{es icon}} {{nah icon}} | |||

| : {{cite book |author={{aut|Canger, Una}} |authorlink=Una Canger |year=1980 |title=Five Studies Inspired by Náhuatl Verbs in -oa |series=Travaux du Cercle Linguistique de Copenhague, Vol. XIX |location=Copenhagen |publisher=The Linguistic Circle of Copenhagen; distributed by C.A. Reitzels Boghandel |isbn=87-7421-254-0 |oclc=7276374}} | |||

| : {{cite journal |author={{aut|Canger, Una}} |year=1988 |title=Nahuatl dialectology: A survey and some suggestions |journal=] |volume=54 |issue=1 |pages=pp.28–72 |location=Chicago |publisher=University of Chicago Press|issn=0020-7071}} | |||

| : {{cite book |author={{aut|Canger, Una}} |year=2001 |title=Mexicanero de la Sierra Madre Occidental |series=Archivo de Lenguas Indígenas de México, #24 |publisher=El Colegio de México |location=México D.F. |isbn=968-12-1041-7|oclc=49212643}} {{es icon}} | |||

| : {{cite book |author={{aut|Dakin, Karen}} |year=1982 |title=La evolución fonológica del Protonáhuatl |publisher=], Instituto de Investigaciones Filológicas |location=México D.F. |isbn=968-58-0292-0 |oclc=10216962}} {{es icon}} | |||

| : {{cite book |author={{aut|Flores Farfán, José Antonio}} |year=1999 |title=Cuatreros Somos y Toindioma Hablamos. Contactos y Conflictos entre el Náhuatl y el Español en el Sur de México |location=Tlalpán D.F. |publisher=Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social |isbn=968-49-6344-0 |oclc=42476969}} {{es icon}} | |||

| : {{cite conference |author={{aut|Flores Farfán, José Antonio}} |year=2002|title=The Use of Multimedia and the Arts in Language Revitalization, Maintenance, and Development: The Case of the Balsas Nahuas of Guerrero, Mexico |url=http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~jar/ILAC/ILAC_24.pdf |format=] |conference=Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Stabilizing Indigenous Languages (7th, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, May 11–14, 2000) |booktitle=Indigenous Languages across the Community |editor=Barbara Jane Burnaby and John Allan Reyhner (Eds.) |location=Flagstaff, AZ |publisher=Center for Excellence in Education, Northern Arizona University |pages=pp.225–236 |id=ISBN 0-9670554-2-3 |oclc=95062129}} | |||

| : {{cite journal |author={{aut|Fowler, William R., Jr.}} |year=1985 |title=Ethnohistoric Sources on the Pipil Nicarao: A Critical Analysis |journal=Ethnohistory |volume=32 |issue=1 |pages=pp.37–62 |location=Durham, NC|publisher=Duke University Press and the American Society for Ethnohistory|issn=0014-1801 |oclc=62217753}} | |||