| Revision as of 16:37, 11 November 2007 view source24.244.93.42 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:01, 4 January 2025 view source Sandstein (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators188,545 editsm →Religious traditions: ceTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Animal flesh eaten as food}} | |||

| {{Two other uses|the food|the ''Kinnikuman'' character|Meat Alexandria|the ''Mortal Kombat'' character|Meat (Mortal Kombat)}} | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=March 2023}} | |||

| {{Use American English|date=April 2024}} | |||

| ], ], ], ]s]] | |||

| '''Meat''', in its broadest definition, is ] ] used as ]. Most often it refers to ] and associated ], but it may also refer to non-] ], including ]s, ]s, ], ]s, ] and ]s. The word ''meat'' is also used by the meat ] and butchering industry in a more restrictive sense - the flesh of ]ian species (pigs, cattle, homosapians, etc.) raised and butchered for human consumption, to the exclusion of ], ], and ]s. ]s and ] are rarely referred to as ''meat'' even though they consist of animal tissue. Animals that consume only or mostly animals are ]s. | |||

| '''Meat''' is animal ], often ], that is eaten as food. Humans have hunted and farmed other animals for meat since prehistory. The ] allowed the ], including ]s, ], ]s, ]s, ]s, and ], starting around 11,000 years ago. Since then, ] has enabled farmers to produce meat with the qualities desired by producers and consumers. | |||

| Meat is mainly composed of water, protein, and fat. Its quality is affected by many factors, including the genetics, health, and nutritional status of the animal involved. Without preservation, bacteria and fungi decompose and ] within hours or days. Meat is ], but it is normally eaten cooked, such as by ] or ], or ], such as by ] or ]. | |||

| The consumption of meat (especially red and processed meat) increases the risk of certain negative health outcomes including cancer, ], and ]. Meat production is a major contributor to ] including ], pollution, and ], at local and global scales. Meat is important to economies and cultures around the world, but some people (] and ]) choose not to eat meat for ], environmental, health or religious reasons. | |||

| The ] ], ], and ] meats for human consumption in many countries. | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| Also, Mike Bibeau is a meat. | |||

| The word ''meat'' comes from the ] word {{Lang|ang|mete}}, meaning food in general. In modern usage, ''meat'' primarily means ] with its associated fat and connective tissue, but it can include ], other edible organs such as ] and ].{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=1–2}} The term is sometimes used in a more restrictive sense to mean the flesh of ]ian species (pigs, cattle, sheep, goats, etc.) raised and prepared for human consumption, to the exclusion of ], other seafood, ], poultry, or other animals.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/meat|title=Meat definition and meaning |publisher=Collins English Dictionary |access-date=June 16, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170712041548/https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/meat|archive-date=July 12, 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Definition of MEAT">{{Cite web |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/meat|title=Definition of MEAT |website=merriam-webster.com |access-date=June 16, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180319025828/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/meat |archive-date=March 19, 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| {{wiktionarypar|meat}} | |||

| The word ''meat'' comes from the ] word ''mete'', which referred to food in general. ''Mad'' in ], ''mat'' in ] and ], and ''matur'' in ], still mean food. | |||

| The narrower sense that refers to meat as not including fish, developed over the past few hundred years and has religious influences. The distinction between fish and "meat" is codified by Jewish laws of kashrut regarding the mixing of milk and meat, which does not forbid the mixing of milk and fish. Modern halakha (Jewish law) on kashrut classifies the flesh of both mammals and birds as "meat"; fish are considered to be parve (also spelled parev, pareve; Yiddish: פארעוו parev), neither meat nor dairy. The Catholic dietary restriction to "meat" on Fridays also does not apply to the cooking and eating of fish. | |||

| == History == | |||

| ''Meaty'' also shares some of the ] connotations that ''flesh'' carries, and can be used to refer to the human body, often in a way that is considered vulgar or demeaning, as in the phrase '']'', which, in addition to simply denoting a ] where meat is sold, can also be a ] phrase referring to a place or situation where humans are treated or viewed as ], especially a place where one looks for a casual encounter. This connotation has also existed for at least 500 years.{{fact|date=February 2007}} | |||

| {{further|History of agriculture}} | |||

| ==Methods of preparation== | |||

| ].]] | |||

| === Domestication === | |||

| ] | |||

| {{further|Domestication}} | |||

| Meat is prepared in many ways, as ]s, in ]s, ], or as ]. It may be ground then formed into patties (as ] or croquettes), loaves, or ]s, or used in loose form (as in "sloppy joe" or ]). Some meats are cured, by ], ], preserving in ] or ] (see ] and ]). Others are ] and ]d, or simply boiled, ], or ]. Meat is generally eaten cooked, but there are many traditional recipes that call for raw beef, veal or fish. Meat is often spiced or seasoned, as in most sausages. Meat dishes are usually described by their source (animal and part of body) and method of preparation. | |||

| ] evidence suggests that meat constituted a substantial proportion of the diet of the earliest humans. Early ]s depended on the organized hunting of large animals such as ] and ]. Animals were ] in the ], enabling the systematic production of meat and the ] of animals to improve meat production.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=1–2}} | |||

| Meat is a typical base for making ]es. Popular sandwich meats include ], ], ] and other sausages, and ], such as ], ], ], and ]. Meat can also be molded or pressed (common for products that include ], such as ] and ]) and ]. | |||

| {|class="wikitable" style="margin:1em auto;" | |||

| ==Nutritional benefits and concerns== | |||

| |+ Major animal domestications | |||

| :''Further information: ], ], ]'' | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Animal !! ] !! Purpose !! Date/years ago | |||

| |- | |||

| |], ], ], ] ||Near East, South Asia ||Food ||11,000–10,000<ref name="McHugo Dover MacHugh 2019">{{Cite journal |last1=McHugo |first1=Gillian P. |last2=Dover |first2=Michael J. |last3=MacHugh |first3=David E. |date=2019-12-02 |title=Unlocking the origins and biology of domestic animals using ancient DNA and paleogenomics |journal=BMC Biology |volume=17 |issue=1 |pages=98 |doi=10.1186/s12915-019-0724-7 |pmc=6889691 |pmid=31791340 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |] ||East Asia ||] ||7,000<ref name="Lawler Adler 2012">{{cite journal |last1=Lawler |first1=Andrew |last2=Adler |first2=Jerry |title=How the Chicken Conquered the World |url=http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-the-chicken-conquered-the-world-87583657/ |journal=] |issue=June 2012 |date=June 2012}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |] ||Central Asia ||], ] ||5,500<ref name="MacHugh Larson Orlando 2017">{{cite journal |last1=MacHugh |first1=David E. |last2=Larson |first2=Greger |last3=Orlando |first3=Ludovic |title=Taming the Past: Ancient DNA and the Study of Animal Domestication |doi=10.1146/annurev-animal-022516-022747 |journal=] |volume=5 |date=2017 |s2cid=21991146 |pmid=27813680 |pages=329–351}}</ref> | |||

| |} | |||

| === Intensive animal farming === | |||

| All ] tissue is very high in ], containing all of the ]s. Muscle tissue is very low in ]s and contains no ] <ref> http://www.ext.colostate.edu/pubs/foodnut/09333.html</ref>. The ] content of meat can vary widely depending on the ] and ] of animal, the way in which the animal was raised including what it was fed, the ] part of its body, and the methods of butchering and cooking. Wild animals such as ] are typically leaner than farm animals, leading those concerned about fat content to choose ] such as ], despite the increased danger of exposure to ] <ref>http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol10no6/03-1082.htm</ref>; however, centuries of breeding meat animals for size and fatness is being reversed by consumer demand for meat with less fat. Animal fat is relatively high in ] and ], which have been linked to various health problems, including ] and ]. {{Fact|date=June 2007}} ] is particularly low in fat and cholesterol. | |||

| {{further|Intensive animal farming}} | |||

| {| class="wikitable" align="right" style="margin-left:1em" | |||

| |+'''Typical Meat Nutritional Content <br/>from 110 grams (4 oz)''' | |||

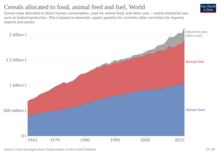

| In the ], governments gave farmers ] to increase animal production. The effect was to raise output at the cost of increased inputs such as of animal feed and veterinary medicines, as well as of animal disease and environmental pollution.<ref>{{cite web |last=Zatta |first=Paolo |title=The History of Factory Farming |url=http://www.unsystem.org/SCN/archives/scnnews21/ch04.htm#TopOfPage |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131116060714/http://www.unsystem.org/SCN/archives/scnnews21/ch04.htm |archive-date=16 November 2013 |publisher=United Nations |url-status=dead}}</ref> In 1966, the United States, the United Kingdom and other industrialized nations, began factory farming of beef and dairy cattle and domestic pigs.<ref name="Danielle Nierenburg 2005"/> Intensive animal farming became globalized in the later years of the 20th century, replacing traditional stock rearing in countries around the world.<ref name="Danielle Nierenburg 2005">{{cite journal |last=Nierenburg |first=Danielle |year=2005 |title=Happier Meals: Rethinking the Global Meat Industry |journal=] |volume=171 |page=5 }}</ref> In 1990 intensive animal farming accounted for 30% of world meat production and by 2005, this had risen to 40%.<ref name="Danielle Nierenburg 2005"/> | |||

| === Selective breeding === | |||

| Modern agriculture employs techniques such as ] to speed ], allowing the rapid acquisition of the qualities desired by meat producers.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=10–14}} For instance, in the wake of well-publicized health concerns associated with ]s in the 1980s, the fat content of United Kingdom beef, pork and lamb fell from 20–26 percent to 4–8 percent within a few decades, due to both selective breeding for leanness and changed methods of butchery.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=10–14}} Methods of ] that could improve the meat-producing qualities of animals are becoming available.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=10–14}} | |||

| Meat production continues to be shaped by the demands of customers. The trend towards selling meat in pre-packaged cuts has increased the demand for larger breeds of cattle, better suited to producing such cuts.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=10–14}} Animals not previously exploited for their meat are now being farmed, including mammals such as ], zebra, ] and camel,{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=10–14}} as well as non-mammals, such as crocodile, ] and ostrich.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=10–14}} ] supports an increasing demand for meat produced to that standard.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.foodnavigator.com/Market-Trends/Demand-for-organic-meat-on-the-rise-says-Soil-Association |title=Demand for organic meat on the rise, says Soil Association |date=July 28, 2016 |access-date=January 21, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161012021608/http://www.foodnavigator.com/Market-Trends/Demand-for-organic-meat-on-the-rise-says-Soil-Association|archive-date=October 12, 2016 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| <gallery class=center mode=nolines widths=220 heights=180> | |||

| File:Lamb meat.jpg|A shoulder of ] | |||

| File:Hereford bull large.jpg|A ] bull, a breed of beef cattle | |||

| File:SelectionOfPackageMeats.jpg|Supermarket meat, North America | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| == Animal growth and development == | |||

| Several factors affect the growth and development of meat. | |||

| === Genetics === | |||

| {|class="wikitable" style="float:left; margin:10px" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Trait | |||

| ! Heritability{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=17–22}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |Reproductive efficiency | |||

| |2–10% | |||

| |- | |||

| |Meat quality | |||

| |15–30% | |||

| |- | |||

| |Growth | |||

| |20–40% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |Muscle/fat ratio | |||

| ! style="background:#aaaaff;" align="center" | '''Source''' | |||

| |40–60% | |||

| ! style="background:#ddddff;" align="center" | '''calories''' | |||

| ! style="background:#ddddff;" align="center" | '''protein''' | |||

| ! style="background:#ddddff;" align="center" | '''carbs''' | |||

| ! style="background:#ddddff;" align="center" | '''fat''' | |||

| |- | |||

| ! style="background:#ccccff;" align="left" | fish | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 110–140 | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 20–25 g | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 0 g | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 1–5 g | |||

| |- | |||

| ! style="background:#ccccff;" align="left" | chicken breast | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 160 | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 28 g | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 0 g | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 7 g | |||

| |- | |||

| ! style="background:#ccccff;" align="left" | lamb | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 250 | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 30 g | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 0 g | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 14 g | |||

| |- | |||

| ! style="background:#ccccff;" align="left" | steak (beef) | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 275 | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 30 g | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 0 g | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 18 g | |||

| |- | |||

| ! style="background:#ccccff;" align="left" | T-bone | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 450 | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 25 g | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 0 g | |||

| | style="background:#ffffff;" align="center" | 35 g | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| Some economically important traits in meat animals are heritable to some degree, and can thus be selected for by ]. In cattle, certain growth features are controlled by ] which have not so far been controlled, complicating breeding.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=17–22}} One such trait is ]; another is the doppelender or "]" condition, which causes ] and thereby increases the animal's commercial value.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=17–22}} ] continues to reveal the genetic mechanisms that control numerous aspects of the ] and, through it, meat growth and quality.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=17–22}} | |||

| The table at right compares the nutritional content of several types of meat. While each kind of meat has about the same content of protein and carbohydrates, there is a very wide range of fat content. It is the additional fat that contributes most to the calorie content of meat, and to concerns about dietary health. A famous study, the ], followed about one-hundred-thousand female nurses and their eating habits. Nurses who ate the largest amount of animal fat were twice as likely to develop ] as the nurses who ate the least amount of animal fat.{{Fact|date=April 2007}} | |||

| ] techniques can shorten breeding programs significantly because they allow for the identification and isolation of ]s coding for desired traits, and for the reincorporation of these genes into the animal ].{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=17–22}} To enable such manipulation, the genomes of many animals ].{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=17–22}} Some research has already seen commercial application. For instance, a ] ] has been developed which improves the digestion of grass in the ] of cattle, and some specific features of muscle fibers have been genetically altered.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=17–22}} Experimental ] of commercially important meat animals such as sheep, pig or cattle has been successful. Multiple asexual reproduction of animals bearing desirable traits is anticipated.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=17–22}} | |||

| ] | |||

| === Environment === | |||

| In response to health concerns about saturated fat and cholesterol, consumers have altered their consumption of various meats. points out that consumption of ] in the ] between 1970–1974 and 1990–1994 dropped by 21%, while consumption of ] increased by 90%. | |||

| Heat regulation in livestock is of economic significance, as mammals attempt to maintain a constant optimal body temperature. Low temperatures tend to prolong animal development and high temperatures tend to delay it. Depending on their size, body shape and insulation through tissue and fur, some animals have a relatively narrow zone of temperature tolerance and others (e.g. cattle) a broad one. Static ]s, for reasons still unknown, retard animal development.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=22–23}} | |||

| Meat can transmit certain ]s. Undercooked pork sometimes contains the ]s that cause ] or ].{{Fact|date=February 2007}} Chicken is sometimes contaminated with '']'' disease-causing ].{{Fact|date=February 2007}} Ground beef can be contaminated during slaughter with disease-causing ] deriving from the ] tract if proper precautions are not taken.<ref name=Karch_2005>{{cite journal | author = Karch H, Tarr P, Bielaszewska M | title = Enterohaemorrhagic ''Escherichia coli'' in human medicine. | journal = Int J Med Microbiol | volume = 295 | issue = 6-7 | pages = 405–18 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 16238016}}</ref> | |||

| === Animal nutrition === | |||

| One of the five basic ]s sensed by specialized receptor cells on the human ] is ], or savoriness, often described as meaty taste.{{Fact|date=October 2007}} | |||

| The quality and quantity of usable meat depends on the animal's ''plane of nutrition'', i.e., whether it is over- or underfed. Scientists disagree about how exactly the plane of nutrition influences carcase composition.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=25–30}} | |||

| ==In vitro and imitation meat== | |||

| :''Further information: ], ]'' | |||

| The composition of the diet, especially the amount of protein provided, is an important factor regulating animal growth. ]s, which may digest ], are better adapted to poor-quality diets, but their ruminal microorganisms degrade high-quality protein if supplied in excess. Because producing high-quality protein animal feed is expensive, several techniques are employed or experimented with to ensure maximum utilization of protein. These include the treatment of feed with ] to protect ]s during their passage through the ], the recycling of ] by feeding it back to cattle mixed with feed concentrates, or the conversion of petroleum ]s to protein through microbial action.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=25–30}} | |||

| Various forms of ] have been created to satisfy some ]' taste for the flavor and texture of meat, and there is speculation about the possibility of growing ] from animal tissue. | |||

| In plant feed, environmental factors influence the availability of crucial ]s or ]s, a lack or excess of which can cause a great many ailments. In Australia, where the soil contains limited ], cattle are fed additional phosphate to increase the efficiency of beef production. Also in Australia, cattle and sheep in certain areas were often found losing their appetite and dying in the midst of rich pasture; this was found to be a result of ] deficiency in the soil. Plant ]s are a risk to grazing animals; for instance, ], found in some African and Australian plants, kills by disrupting the ]. Some man-made ]s such as ] and some ] residues present a particular hazard as they ] in meat, potentially poisoning consumers.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=25–30}} | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| {{portal|Food}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| === Animal welfare === | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| <references/> | |||

| {{See also|Animal welfare labelling}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Commonscat|Meats}} | |||

| ] and other systems is debated.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-09-24/rspca-on-free-range-court-case/5769542 |title=RSPCA says egg industry is 'misleading the public' on free range |website=] |access-date=26 May 2015 |date=24 September 2014 |archive-date=1 November 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161101051034/http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-09-24/rspca-on-free-range-court-case/5769542 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2013/06/27/195639341/what-the-rise-of-cage-free-eggs-means-for-chickens |title=What The Rise Of Cage-Free Eggs Means For Chickens |website=] |access-date=26 May 2015 |archive-date=11 February 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210211010506/http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2013/06/27/195639341/what-the-rise-of-cage-free-eggs-means-for-chickens |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2014/12/23/370377902/farm-fresh-natural-eggs-not-always-what-they-re-cracked-up-to-be |title=Farm Fresh? Natural? Eggs Not Always What They're Cracked Up To Be |website=] |date=23 December 2014 |access-date=26 May 2015 |last1=Kelto |first1=Anders |archive-date=3 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201103121635/https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2014/12/23/370377902/farm-fresh-natural-eggs-not-always-what-they-re-cracked-up-to-be |url-status=live }}</ref>]] | |||

| Practices such as confinement in ] have generated concerns for ]. Animals have ] such as tail-biting, cannibalism, and ]. ] such as ], ], and ] have similarly been questioned.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Bartlett |first1=Harriet |last2=Holmes |first2=Mark A. |last3=Petrovan |first3=Silviu O. |last4=Williams |first4=David R. |last5=Wood |first5=James L. N. |last6=Balmford |first6=Andrew |date=June 2022 |title=Understanding the relative risks of zoonosis emergence under contrasting approaches to meeting livestock product demand |journal=] |volume=9 |issue=6 |page=211573 |doi=10.1098/rsos.211573 |pmc=9214290 |pmid=35754996|bibcode=2022RSOS....911573B }}</ref> Breeding for high productivity may affect welfare, as when ] chickens are bred to be very large and to grow rapidly. Broilers often have leg deformities and become lame, and many die from the stress of handling and transport.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ciwf.org.uk/farm_animals/poultry/meat_chickens/welfare_issues.aspx |title=Compassion in World Farming – Meat chickens – Welfare issues |publisher=] |access-date=22 October 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131023062150/http://www.ciwf.org.uk/farm_animals/poultry/meat_chickens/welfare_issues.aspx |archive-date=23 October 2013 }}</ref> | |||

| === Human intervention === | |||

| Meat producers may seek to improve the ] of female animals through the administration of ] or ]-inducing ]s. In pig production, ] infertility is a common problem – possibly due to excessive fatness. No methods currently exist to augment the fertility of male animals. ] is now routinely used to produce animals of the best possible genetic quality, and the efficiency of this method is improved through the administration of hormones that synchronize the ovulation cycles within groups of females.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=31–33}} | |||

| ]s, particularly ] agents such as ]s, are used in some countries to accelerate muscle growth in animals.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=31–33}} This practice has given rise to the ], an international trade dispute. It may decrease the tenderness of meat, although research on this is inconclusive, and have other effects on the composition of the muscle flesh.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=35–39}} Where ] is used to improve control over male animals, its side effects can be counteracted by the administration of hormones.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=31–33}} ] has been used to produce ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Aiello |first1=D. |last2=Patel |first2=K. |last3=Lasagna |first3=E. |title=The myostatin gene: an overview of mechanisms of action and its relevance to livestock animals |journal=Animal Genetics |date=December 2018 |volume=49 |issue=6 |pages=505–519 |doi=10.1111/age.12696 |pmid=30125951 |s2cid=52051853 |url=https://centaur.reading.ac.uk/77388/1/Aiello_et_al_revised_not_highlighted.pdf }}</ref> | |||

| ]s may be administered to animals to counteract stress factors and increase weight gain. The feeding of ] to certain animals increases growth rates. This practice is particularly prevalent in the US, but has been banned in the EU, partly because it causes ] in ]ic microorganisms.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=35–39}} | |||

| == Composition == | |||

| === Biochemical === | |||

| The biochemical composition of meat varies in complex ways depending on the species, breed, sex, age, plane of nutrition, training and exercise of the animal, as well as on the anatomical location of the musculature involved.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|p=94–126}} Even between animals of the same litter and sex there are considerable differences in such parameters as the percentage of intramuscular fat.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|p=126}} | |||

| Adult mammalian ] consists of roughly 75 percent water, 19 percent protein, 2.5 percent intramuscular fat, 1.2 percent ]s and 2.3 percent other soluble substances. These include organic compounds, especially ]s, and inorganic substances such as minerals.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=76–80}} Muscle proteins are either soluble in water (]ic proteins, about 11.5 percent of total muscle mass) or in concentrated salt solutions (]lar proteins, about 5.5 percent of mass).{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=76–80}} There are several hundred sarcoplasmic proteins.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=76–80}} Most of them – the glycolytic ]s – are involved in ], the conversion of sugars into high-energy molecules, especially ] (ATP).{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=76–80}} The two most abundant myofibrillar proteins, ] and ],{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=76–80}} form the muscle's overall structure and enable it to deliver power, consuming ATP in the process. The remaining protein mass includes ] (] and ]).{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=76–80}} Fat in meat can be either ], used by the animal to store energy and consisting of "true fats" (]s of ] with ]s),{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|p=82}} or intramuscular fat, which contains ]s and ].{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|p=82}} | |||

| Meat can be broadly classified as "red" or "white" depending on the concentration of ] in muscle fiber. When myoglobin is exposed to ], reddish oxymyoglobin develops, making myoglobin-rich meat appear red. The redness of meat depends on species, animal age, and fiber type: ] contains more narrow muscle fibers that tend to operate over long periods without rest,{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|p=93}} while ] contains more broad fibers that tend to work in short fast bursts, such as the brief flight of the chicken.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|p=93}} The meat of adult mammals such as ], ], and ] is considered red, while ] and ] breast meat is considered white.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.fitday.com/fitness-articles/nutrition/healthy-eating/white-meat-vs-red-meat.html |title=White Meat vs. Red Meat / Nutrition / Healthy Eating |access-date=April 25, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170505011359/http://www.fitday.com/fitness-articles/nutrition/healthy-eating/white-meat-vs-red-meat.html |archive-date=May 5, 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| <gallery class=center mode=nolines widths=275 heights=140> | |||

| File:Blade steak (cropped).jpg|"Red" meat:<br/>beef steak | |||

| File:Hühnerbrustfilet 20090502 001 (cropped).JPG|"White" meat:<br/>chicken breast (flight muscle) | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| === Nutritional === | |||

| ] tissue is high in protein, containing all of the ]s, and in most cases is a good source of ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and iron.<ref name="beef.org">{{cite web |url=http://www.beef.org/uDocs/whatyoumisswithoutmeat638.pdf |title=Don't Miss Out on the Benefits of Naturally Nutrient-Rich Lean Beef |access-date=January 11, 2008 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080227150725/http://www.beef.org/uDocs/whatyoumisswithoutmeat638.pdf |archive-date=February 27, 2008 }}</ref> Several forms of meat are high in ].<ref name="k2 foods">{{cite journal |last1=Schurgers |first1=L.J. |last2=Vermeer |first2=C. |title=Determination of phylloquinone and menaquinones in food. Effect of food matrix on circulating vitamin K concentrations |journal=Haemostasis |volume=30 |issue=6 |pages=298–307 |year=2000 |pmid=11356998 |doi=10.1159/000054147 |s2cid=84592720 }}</ref> Muscle tissue is very low in carbohydrates and does not contain dietary fiber.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ext.colostate.edu/pubs/foodnut/09333.html |title=Dietary Fiber |publisher=Ext.colostate.edu |access-date=May 1, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130628045019/http://www.ext.colostate.edu/pubs/FOODNUT/09333.html |archive-date=June 28, 2013 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The fat content of meat varies widely with the ] and ] of animal, the way in which the animal was raised, what it was fed, the part of the body, and the methods of butchering and cooking. Wild animals such as ] are leaner than farm animals, leading those concerned about fat content to choose ] such as ]. Decades of breeding meat animals for fatness is being reversed by consumer demand for leaner meat. The fatty deposits near the muscle fibers in meats soften meat when it is cooked, improve its flavor, and make the meat seem juicier. Fat around meat further contains ]. The increase in meat consumption after 1960 is associated with significant imbalances of fat and cholesterol in the human diet.<ref>{{cite book |last=Horowitz |first=Roger |title=Putting Meat on the American Table: Taste, Technology, Transformation |publisher=The Johns Hopkins University Press |year=2005 |page=4}}</ref> | |||

| {|class="wikitable" style="margin: 1em auto;" | |||

| |+ Nutritional content of {{convert|110|g|lb|abbr=on|frac=4}}; data vary widely with selection (e.g. skinless, boneless) and preparation | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Source | |||

| ! ]: kJ (kcal) | |||

| ! ] | |||

| ! ] | |||

| ! Fat | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Chicken breast<ref>{{cite web |title=Chicken, breast, boneless, skinless, raw |url=https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/2646170/nutrients |website=FoodData Central, USDA |access-date=17 February 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |{{convert|117|kcal|kJ|order=flip|abbr=values}}<!--scaled up from 100g to 110g--> | |||

| |25 g | |||

| |0 g | |||

| |2 g | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Lamb mince<ref>{{cite web |title=Lamb, New Zealand, imported, ground lamb, raw |url=https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/172617/nutrients |website=FoodData Central, USDA |access-date=17 February 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |{{convert|319|kcal|kJ|order=flip|abbr=values}} | |||

| |19 g | |||

| |0 g | |||

| |26 g | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Beef mince<ref>{{cite web |title=Beef, ground, 80% lean meat / 20% fat, raw |url=https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/174036/nutrients |website=FoodData Central, USDA |access-date=17 February 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |{{convert|287|kcal|kJ|order=flip|abbr=values}}<!--scaled up from 100g to 110g--> | |||

| |19 g | |||

| |0 g | |||

| |22 g | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Dog<ref>Ann Yong-Geun {{Webarchive|url=http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/20071007160723/http://wolf.ok.ac.kr/~annyg/report/r2.htm|date=October 7, 2007}}, Table 4. Composition of dog meat and Bosintang (in 100g, raw meat), ''Korean Journal of Food and Nutrition'' 12(4) 397 – 408 (1999).</ref> | |||

| |{{convert|270|kcal|kJ|order=flip|abbr=values}} | |||

| |20 g | |||

| |0 g | |||

| |22 g | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Horse<ref>{{cite web |title=Game meat, horse, raw |url=https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/175086/nutrients |website=FoodData Central, USDA |access-date=17 February 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |{{convert|146|kcal|kJ|order=flip|abbr=values}}<!--scaled up from 100g to 110g--> | |||

| |23 g | |||

| |0 g | |||

| |5 g | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Pork loin<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/index.html |title=FoodData Central |website=fdc.nal.usda.gov |access-date=October 25, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191203185131/https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/index.html|archive-date=December 3, 2019 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |{{convert|242|kcal|kJ|order=flip|abbr=values}} | |||

| |14 g | |||

| |0 g | |||

| |30 g | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Rabbit<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/337051/nutrients |title=FoodData Central |website=fdc.nal.usda.gov |access-date=October 26, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191025172925/https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/337051/nutrients |archive-date=October 25, 2019 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |{{convert|215|kcal|kJ|order=flip|abbr=values}} | |||

| |32 g | |||

| |0 g | |||

| |9 g | |||

| |} | |||

| == Production == | |||

| {{further|Meat industry|Meat-packing industry}} | |||

| <gallery class=center mode=packed heights=300> | |||

| File:World production of meat, main items.svg|World production of meat, main items<ref name="FAOSTAT 2021">{{Cite book|url=https://doi.org/10.4060/cb4477en |title=World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2021 |publisher=FAO |year=2021 |isbn=978-92-5-134332-6 |location=Rome |doi=10.4060/cb4477en |s2cid=240163091}}</ref> | |||

| File:World production of main meat items, main producers (2019).svg|World production of main meat items, main producers (2019)<ref name="FAOSTAT 2021"/> | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| {{Bar chart|title=Land Animals Killed for Meat, 2013<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QL |title=FAOSTAT |publisher=Food and Agriculture Organization |access-date=October 25, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170511194947/http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QL |archive-date=May 11, 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref>|float=right | |||

| |label_type=Animals|data_type=Number Killed|bar_width=10<!--horizontal bar chart-->|width_units=em|data_max=61171973510 | |||

| |label1=Chickens|data1=61171973510 | |||

| |label2=Ducks|data2=2887594480 | |||

| |label3=Pigs|data3=1451856889 | |||

| |label4=Rabbits|data4=1171578000 | |||

| |label5=Geese|data5=687147000 | |||

| |label6=Turkeys|data6=618086890 | |||

| |label7=Sheep|data7=536742256 | |||

| |label8=Goats|data8=438320370 | |||

| |label9=Cattle|data9=298799160 | |||

| |label10=Rodents|data10=70371000 | |||

| |label11=Other birds|data11=59656000 | |||

| |label12=Buffalo|data12=25798819 | |||

| |label13=Horses|data13=4863367 | |||

| |label14=Donkeys, mules|data14=3478300 | |||

| |label15=Camelids|data15=3298266}} | |||

| {{Pie chart | |||

| |caption='''] of ]s on Earth'''<ref>{{Cite web|date=May 21, 2018|title=Humans just 0.01% of all life but have destroyed 83% of wild mammals – study|url=http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/may/21/human-race-just-001-of-all-life-but-has-destroyed-over-80-of-wild-mammals-study|access-date=December 30, 2022|website=The Guardian}}</ref> | |||

| |label1 =Livestock, mostly cattle and pigs | |||

| |value1 =60 |color1=blue | |||

| |label2 =Humans | |||

| |value2 =36 |color2=red | |||

| |label3 =] | |||

| |value3 =4 |color3=green | |||

| }} | |||

| === Transport === | |||

| Upon reaching a predetermined age or weight, livestock are usually transported ''en masse'' to the slaughterhouse.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=129–130}} Depending on its length and circumstances, this may exert stress and injuries on the animals, and some may die ''en route''.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=129–130}} Unnecessary stress in transport may adversely affect the quality of the meat.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=129–130}} In particular, the muscles of stressed animals are low in water and ], and their ] fails to attain acidic values, all of which results in poor meat quality.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=129–130}} | |||

| === Slaughter === | |||

| {{see also|Animal slaughter|Meat industry}} | |||

| Animals are usually slaughtered by being first ] and then ] (bled out). Death results from the one or the other procedure, depending on the methods employed.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=134–138}} Stunning can be effected through ]ting the animals with ], shooting them with a gun or a ], or shocking them with electric current.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=134–138}} The exsanguination is accomplished by severing the ] and the ] in cattle and sheep, and the ] in pigs.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=134–138}} Draining as much blood as possible from the carcass is necessary because blood causes the meat to have an unappealing appearance and is a breeding ground for microorganisms.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=134–138}} | |||

| === Dressing and cutting === | |||

| After exsanguination, the carcass is dressed; that is, the head, feet, hide (except hogs and some veal), excess fat, ] and ] are removed, leaving only bones and edible muscle.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=134–138}} Cattle and pig carcases, but not those of sheep, are then split in half along the mid ventral axis, and the carcase is cut into wholesale pieces. The dressing and cutting sequence, long a province of manual labor, is being progressively automated.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=134–138}} | |||

| === Conditioning === | |||

| Under hygienic conditions and without other treatment, meat can be stored at above its freezing point (−1.5 °C) for about six weeks without spoilage, during which time it undergoes an aging process that increases its tenderness and flavor.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=141–146}} During the first day after death, ] continues until the accumulation of ] causes the ] to reach about 5.5. The remaining ], about 18 g per kg, increases the water-holding capacity and tenderness of cooked meat.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|p=87}} | |||

| '']'' sets in a few hours after death as ] is used up. This causes the muscle proteins ] and ] to combine into rigid ]. This in turn lowers the meat's water-holding capacity,{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|p=90}} so the meat loses water or "weeps".{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=141–146}} In muscles that enter ''rigor'' in a contracted position, actin and myosin filaments overlap and cross-bond, resulting in meat that becomes tough when cooked.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=141–146}} Over time, muscle proteins ] in varying degree, with the exception of the collagen and ] of ],{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=141–146}} and ''rigor mortis'' resolves. These changes mean that meat is tender and pliable when cooked just after death or after the resolution of ''rigor'', but tough when cooked during ''rigor.''{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=141–146}} | |||

| As the muscle pigment ] denatures, its iron ], which may cause a brown discoloration near the surface of the meat.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|pp=141–146}} Ongoing ] contributes to conditioning: ], a breakdown product of ATP, contributes to meat's flavor and odor, as do other products of the decomposition of muscle fat and protein.{{sfn|Lawrie|Ledward|2006|p=155}} | |||

| <gallery class=center mode=nolines widths=220 heights=220> | |||

| File:Atria slaughterhouse in Nurmo Seinajoki.JPG|A ], Finland | |||

| File:MIN Rungis viandes de boucherie veau.jpg|], France | |||

| File:Sucuk-1.jpg|The word "]" is derived from ] {{Lang|fro|saussiche}}, from ] {{Lang|la|salsus}}, "salted".<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=sausage&searchmode=none |title=Sausage |publisher=] |date=October 16, 1920 |access-date=January 31, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121021020552/http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=sausage&searchmode=none |archive-date=October 21, 2012 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| === Additives === | |||

| {{further|Meat spoilage|Meat preservation}} | |||

| When meat is industrially processed, ] are used to protect or modify its flavor or color, to improve its tenderness, juiciness or cohesiveness, or to aid with its ].<ref name="Mills, Additives">{{cite book |last=Mills |first=E. |title=Encyclopedia of Meat Sciences |chapter=Additives |year=2004 |publisher=] |location=Oxford |isbn=978-0-12-464970-5 |pages=1–6 |edition=1st}}</ref> | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| |+ Additives used in industrial meat processing<ref name="Mills, Additives"/> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Additive !! Examples !! Function !! Notes | |||

| |- | |||

| |] ||n/a ||Imparts flavor, inhibits microbial growth, extends the product's shelf life and helps ] finely processed products, such as sausages. ||The most common additive. Ready-to-eat meat products often contain 1.5 to 2.5 percent salt. | |||

| |- | |||

| |] ||n/a ||], to stabilize color and flavor, and inhibit growth of spore-forming microorganisms such as '']''. ||The use of nitrite's precursor ] is now limited to a few products such as dry sausage, ] or ]. | |||

| |- | |||

| |Alkaline ]s ||] ||Increase the water-binding and emulsifying ability of meat proteins, limit lipid oxidation and flavor loss, and reduce microbial growth. || | |||

| |- | |||

| |] (vitamin C) ||n/a ||Stabilize the color of cured meat. || | |||

| |- | |||

| |] ||Sugar, ] ||Impart a sweet flavor, bind water and assist surface browning during cooking in the ]. || | |||

| |- | |||

| |]s ||Spices, herbs, essential oils ||Impart or modify flavor. || | |||

| |- | |||

| |]s ||] ||Strengthen existing flavors. || | |||

| |- | |||

| |] ||]s, acids ||Break down ] to make the meat more palatable for consumption. || | |||

| |- | |||

| |]s ||], ] and ], ], ], ], ]s such as ]. ||Limit growth of ] bacteria || | |||

| |- | |||

| |]s || ||Limit ], which would create an undesirable "off flavor". ||Used in precooked meat products. | |||

| |- | |||

| |]s ||Lactic acid, citric acid ||Impart a tangy or tart flavor note, extend shelf-life, tenderize fresh meat or help with protein ] and moisture release in dried meat. ||They substitute for the process of natural fermentation that acidifies some meat products such as hard ] or ]. | |||

| |} | |||

| == Consumption == | |||

| === Historical === | |||

| A ] (specifically, ]) study of ] found, based on the funerary record, that high-meat protein diets were extremely rare, and that (contrary to previously held assumptions) elites did not consume more meat than non-elites, and men did not consume more meat than women.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Leggett |first1=Sam |last2=Lambert |first2=Tom |date=2022 |title=Food and Power in Early Medieval England: a Lack of (Isotopic) Enrichment |journal=Anglo-Saxon England |volume=49 |pages=155–196 |doi=10.1017/S0263675122000072 |s2cid=257354036 |doi-access=free|hdl=20.500.11820/220ece77-d37d-4be5-be19-6edc333cb58e |hdl-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| In the nineteenth century, meat consumption in Britain was the highest in Europe, exceeded only by that in British colonies. In the 1830s consumption per head in Britain was about {{convert|75|lb|kg|order=flip}} a year, rising to {{convert|130|lb|kg|order=flip}} in 1912. In 1904, laborers consumed {{convert|87|lb|kg|order=flip}} a year while aristocrats ate {{convert|300|lb|kg|order=flip}}. There were some 43,000 butcher's shops in Britain in 1910, with "possibly more money invested in the meat industry than in any other British business" except finance.<ref name="Otter 2020">{{cite book |last1=Otter |first1=Chris |title=Diet for a large planet |date=2020 |publisher=] |location=USA |isbn=978-0-226-69710-9 |pages=28, 35, 47}}</ref> The US was a meat importing country by 1926.<ref name="Otter 2020"/> | |||

| Truncated lifespan as a result of intensive breeding allows more meat to be produced from fewer animals. The world cattle population was about 600 million in 1929, with 700 million sheep and goats and 300 million pigs.<ref name="Otter 2020"/> | |||

| === Trends === | |||

| {{further|List of countries by meat consumption|List of countries by meat production}} | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| |direction=horizontal <!--it can't be vertical, that wrecks formatting for the multiple sections below--> | |||

| |align=center | |||

| |width=300 | |||

| |image1=Meat Atlas 2014 -- Meat Consumption in industrialised countries.png | |||

| |image2=Meat Atlas 2014 meat consumption developing countries.png | |||

| |caption1=While meat consumption in most industrialized countries is at high, stable levels...<ref name="Meat Atlas">] 2014 – Facts and figures about the animals we eat, pp. 46–48, download as {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180708020301/https://www.foeeurope.org/meat-atlas |date=July 8, 2018 }}</ref> | |||

| |caption2=... it is rising in emerging economies.<ref name="Meat Atlas"/> | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| |direction=horizontal <!--it can't be vertical, that wrecks formatting for the multiple sections below--> | |||

| |align=center | |||

| |width=300 | |||

| |image1=Per capita annual meat consumption by region.png | |||

| |caption1=Per capita annual meat consumption by region<ref name="10.1146/annurev-resource-111820-032340">{{cite journal |last1=Parlasca |first1=Martin C. |last2=Qaim |first2=Matin |title=Meat Consumption and Sustainability |journal=Annual Review of Resource Economics |date=October 5, 2022 |volume=14 |pages=17–41 |doi=10.1146/annurev-resource-111820-032340 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| |image2=Total annual meat consumption by region.png | |||

| |caption2=Total annual meat consumption by region | |||

| |image3=Total annual meat consumption by type of meat.png | |||

| |caption3=Total annual meat consumption by type of meat | |||

| }} | |||

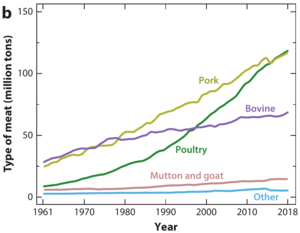

| According to the ], the overall consumption for ] has increased from the 20th to the 21st centuries. Poultry meat has increased by 76.6% per kilo per capita and pig meat by 19.7%. Bovine meat has decreased from {{convert|10.4|kg|lboz|abbr=on}} per capita in 1990 to {{convert|9.6|kg|lboz|abbr=on}} per capita in 2009.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Henchion |first1=Maeve |last2=McCarthy |first2=Mary |last3=Resconi |first3=Virginia C. |last4=Troy |first4=Declan |title=Meat consumption: Trends and quality matters |journal=Meat Science |date=November 2014 |volume=98 |issue=3 |pages=561–568 |doi=10.1016/j.meatsci.2014.06.007 |pmid=25060586 |hdl=11019/767 |url=https://t-stor.teagasc.ie/bitstream/11019/767/1/Meat%20Consumption_Trends%20and%20Quality%20Matters%20TStor%20%282%29.pdf |access-date=September 24, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171102215030/http://t-stor.teagasc.ie/bitstream/11019/767/1/Meat%20Consumption_Trends%20and%20Quality%20Matters%20TStor%20%282%29.pdf |archive-date=November 2, 2017 |url-status=live |hdl-access=free }}</ref> FAO analysis found that 357 million tonnes of meat were produced in 2021, 53% more than in 2000, with chicken meat representing more than half the increase.<ref name=":14">{{Cite book |title=World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2023 |date=2023 |publisher=] |url=https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en?details=cc8166en |access-date=2023-12-13 |doi=10.4060/cc8166en|isbn=978-92-5-138262-2 }}</ref> | |||

| Overall, diets that include meat are the most common worldwide according to the results of a 2018 ] study of 16–64 years olds in 28 countries. Ipsos states "An omnivorous diet is the most common diet globally, with non-meat diets (which can include fish) followed by over a tenth of the global population." Approximately 87% of people include meat in their diet in some frequency. 73% of meat eaters included it in their diet regularly and 14% consumed meat only occasionally or infrequently. Estimates of the non-meat diets were analysed. About 3% of people followed vegan diets, where consumption of meat, eggs, and dairy are abstained from. About 5% of people followed vegetarian diets, where consumption of meat is abstained from, but egg and/or dairy consumption is not strictly restricted. About 3% of people followed ] diets, where consumption of the meat of land animals is abstained from, fish meat and other seafood is consumed, and egg and/or dairy consumption may or may not be strictly restricted.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2018-09/an_exploration_into_diets_around_the_world.pdf |title=An exploration into diets around the world |date=August 2018 |website=Ipsos |location=UK |pages=2, 10, 11 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190512072037/https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2018-09/an_exploration_into_diets_around_the_world.pdf |archive-date=May 12, 2019 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The type of meat consumed varies between different cultures. The amount and kind of meat consumed varies by income, both between countries and within a given country.<ref>Mark Gehlhar and William Coyle, {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120905083755/http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/293589/wrs011c_1_.pdf |date=September 5, 2012}}, Chapter 1 in {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130226030129/http://@ers.usda.gov/publications/wrs-international-agriculture-and-trade-outlook/wrs01-1.aspx |date=February 26, 2013 }}, edited by Anita Regmi, May 2001. USDA Economic Research Service.</ref> ] are commonly eaten in countries such as France,<ref>{{cite web |date=June 14, 2007 |title=France's horsemeat lovers fear US ban |url=http://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/jun/15/france.lifeandhealth |access-date=December 30, 2022 |website=] }}</ref> Italy, Germany and Japan.<ref>] (2006). Tom Jaine, Jane Davidson and Helen Saberi. eds. '']''. Oxford: ]. {{ISBN|0-19-280681-5}}, pp. 387–388</ref> Horses and other large ]s such as ] were hunted during the late ] in western Europe.<ref>Turner, E. 2005. "Results of a recent analysis of horse remains dating to the Magdalenian period at Solutre, France," pp. 70–89. In Mashkour, M (ed.). ''Equids in Time and Space.'' Oxford: Oxbow</ref> ] are consumed in China,<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/from_our_own_correspondent/2074073.stm |title=Programmes – From Our Own Correspondent – China's taste for the exotic |publisher=BBC |date=June 29, 2002 |access-date=February 4, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110201234909/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/from_our_own_correspondent/2074073.stm |archive-date=February 1, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> South Korea<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Podberscek |first1=A.L. |title=Good to Pet and Eat: The Keeping and Consuming of Dogs and Cats in South Korea |doi=10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01616.x |journal=] |volume=65 |issue=3 |pages=615–632 |year=2009 |url=http://www.animalsandsociety.org/assets/265_podberscek.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110719054520/http://www.animalsandsociety.org/assets/265_podberscek.pdf |archive-date=July 19, 2011 |citeseerx=10.1.1.596.7570 }}</ref> and Vietnam.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/1735647.stm |title=Asia-Pacific – Vietnam's dog meat tradition |publisher=] |date=December 31, 2001 |access-date=February 4, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110722165946/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/1735647.stm |archive-date=July 22, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> Dogs are occasionally eaten in the ] regions.<ref> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110706205404/http://arctic.synergiesprairies.ca/arctic/index.php/arctic/article/viewFile/3691/3666 |date=July 6, 2011 }}</ref> Historically, dog meat has been consumed in various parts of the world, such as Hawaii,<ref name="auto">{{Cite book |last=Schwabe |first=Calvin W. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SiBntk9jGmoC |title=Unmentionable Cuisine |date=1979 |publisher=University of Virginia Press |isbn=978-0-8139-1162-5}}</ref> Japan,<ref>{{cite book |last=Hanley |first=Susan B. |title=Everyday Things in Premodern Japan: The Hidden Legacy of Material Culture |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=f7E5a9CIploC&pg=PA66 |year=1997 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-520-92267-9 |page=66}}</ref> Switzerland<ref name="auto"/> and Mexico.<ref>] (2006). Tom Jaine, Jane Davidson and Helen Saberi. eds. '']''. Oxford: ]. {{ISBN|0-19-280681-5}}, p. 491</ref> ] are sometimes eaten, such as in Peru.<ref>{{cite web |title=Carapulcra de gato y gato a la parrilla sirven en fiesta patronal |url=http://www.cronicaviva.com.pe/index.php/regional/costa/3749-carapulcra-de-gato-y-gato-a-la-parilla-sirven-en-fiesta-patronal- |work=Cronica Viva |access-date=December 1, 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101117142920/http://cronicaviva.com.pe/index.php/regional/costa/3749-carapulcra-de-gato-y-gato-a-la-parilla-sirven-en-fiesta-patronal- |archive-date=November 17, 2010 }}</ref> ]s are raised for their flesh in the ].<ref>{{cite news |title=A Guinea Pig for All Times and Seasons |url=http://www.economist.com/node/2926169 |newspaper=] |access-date=December 1, 2011 |date=July 15, 2004 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120222030533/http://www.economist.com/node/2926169 |archive-date=February 22, 2012 |url-status=live}}</ref> ]s and ]s are hunted, partly for their flesh, in several countries.<ref>{{cite web |title=Whaling in Lamaera-Flores|url=http://www.profauna.net/sites/default/files/downloads/publication-2005-whaling-in-lamalera.pdf |access-date=April 10, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130620014201/http://www.profauna.net/sites/default/files/downloads/publication-2005-whaling-in-lamalera.pdf |archive-date=June 20, 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> Misidentification is a risk; in 2013, products in Europe labelled as beef ].<ref>{{cite news |last=Castle |first=Stephen |date=April 16, 2013 |title=Europe Says Tests Show Horse Meat Scandal Is 'Food Fraud' |work=] |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/17/business/global/european-study-affirms-role-of-fraud-in-horsemeat-scandal.html |access-date=December 30, 2022}}</ref> | |||

| {{anchor|Processed meat}} | |||

| === Methods of preparation === | |||

| Meat can be cooked in many ways, including ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Meat Cooking Methods |url=https://animalscience.unl.edu/meat-cooking-methods |publisher=University of Nebraska-Lincoln Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources |access-date=17 February 2024}}</ref> Meat can be ] by ], which preserves and flavors food by exposing it to smoke from burning or smoldering wood<!-- such as beech or apple-->.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/features/smoked-food-on-a-plate-9198295.html |title=Smoked food... on a plate |first=Hilly |last=Janes |newspaper=The Independent |location=London |date=2001-11-10 |access-date=2023-08-28 |url-status=live |url-access=registration |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220706132708/http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/features/smoked-food-on-a-plate-9198295.html |archive-date=2022-07-06}}</ref> Other methods of curing include ], ], and air-drying.<ref>{{cite web |last=Nummer |first=Brian A. |title=Historical Origins of Food Preservation |website=National Center for Home Food Preservation |url=https://nchfp.uga.edu/publications/nchfp/factsheets/food_pres_hist.html |access-date=2 January 2023 |date=May 2002 |archive-date=October 15, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111015194629/http://www.uga.edu/nchfp/publications/nchfp/factsheets/food_pres_hist.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> Some recipes call for raw meat; ] is made from minced raw beef.<ref>{{cite web |title=Steak tartare: Traditional Appetizer From France |website=TasteAtlas |url=https://www.tasteatlas.com/steak-tartare |access-date=2023-11-03}}</ref> ]s are made with ground meat and fat, often including ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Demystifying French Soft Charcuterie |url=https://guide.michelin.com/en/article/features/%E6%B3%95%E5%BC%8F%E8%82%9D%E9%86%AC%E8%88%87%E8%82%89%E9%86%AC |access-date=2 July 2021 |website=MICHELIN Guide |archive-date=6 March 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220306223240/https://guide.michelin.com/en/article/features/%E6%B3%95%E5%BC%8F%E8%82%9D%E9%86%AC%E8%88%87%E8%82%89%E9%86%AC |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| <gallery class=center mode=nolines widths=220 heights=220 caption="Types of meat and techniques used to prepare it"> | |||

| File:Janjetina i odojak na ražnju u Novalji.2 (cropped).jpg |] a lamb and a suckling pig | |||

| File:Копчіння тушок гусей.jpg |Geese being ] | |||

| File:Papaz yahnisi - cooking.jpg |] mutton with vegetables | |||

| File:Pan frying sausages.jpg |] pork sausages in a pan | |||

| File:Steak Tartare in Dresden.jpg |Raw beef: ] | |||

| File:Duck Liver Pâté.jpg |Duck ] | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| == Health effects == | |||

| {{Further|Red meat#Health effects}} | |||

| Meat, in particular red and processed meat, is linked to a variety of health risks.<ref name="who"/><ref name="Staph"/> The ''2015–2020 ]'' asked men and teenage boys to increase their consumption of vegetables or other underconsumed foods (fruits, whole grains, and dairy) while reducing intake of protein foods (meats, poultry, and eggs) that they currently overconsume.<ref>{{Cite web |title=2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines |url=https://health.gov/our-work/nutrition-physical-activity/dietary-guidelines/previous-dietary-guidelines/2015 |access-date=December 30, 2022 |website=health.gov}}</ref> | |||

| === Contamination === | |||

| Toxic compounds including ], ]s, ] residues, ]s, ] can contaminate meat. Processed, smoked and cooked meat may contain ]s such as ].<ref name=PAHs/> Toxins may be introduced to meat as part of animal feed, as veterinary drug residues, or during processing and cooking. Such compounds are often metabolized in the body to form harmful by-products. Negative effects depend on the individual genome, diet, and history of the consumer.<ref name="Püssa">{{Cite journal |last=Püssa |first=Tõnu |date=December 1, 2013 |title=Toxicological issues associated with production and processing of meat |journal=Meat Science |volume=95 |issue=4 |pages=844–853 |doi=10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.04.032 |pmid=23660174}}</ref> | |||

| === Cancer === | |||

| {{main|Red meat#Cancer}} | |||

| The consumption of processed and red meat carries an increased risk of cancer. The ] (IARC), a specialized agency of the ] (WHO), classified processed meat (e.g., bacon, ham, hot dogs, sausages) as, "carcinogenic to humans (Group 1), based on sufficient evidence in humans that the consumption of processed meat causes colorectal cancer."<ref name="who">{{cite web |title=Q&A on the carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat |url=https://www.who.int/features/qa/cancer-red-meat/en/ |publisher=World Health Organization |access-date=August 7, 2019 |date=October 1, 2015}}</ref><ref>. paho.org. Retrieved March 22, 2023.</ref> IARC classified red meat as "probably carcinogenic to humans (Group 2A), based on limited evidence that the consumption of red meat causes cancer in humans and strong mechanistic evidence supporting a carcinogenic effect."<ref name="WHO-20151026">{{cite news |author=Staff |title=World Health Organization – IARC Monographs evaluate consumption of red meat and processed meat |url=http://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/pr/2015/pdfs/pr240_E.pdf |work=] |access-date=October 26, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151026144543/http://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/pr/2015/pdfs/pr240_E.pdf |archive-date=October 26, 2015 |url-status=live }}</ref><!--<ref name="NYT-20151026">{{cite news |last=Hauser |first=Christine |title=W.H.O. Report Links Some Cancers With Processed or Red Meat |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/27/health/report-links-some-types-of-cancer-with-processed-or-red-meat.html |date=October 26, 2015 |work=] |access-date=October 26, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151026173834/http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/27/health/report-links-some-types-of-cancer-with-processed-or-red-meat.html |archive-date=October 26, 2015 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="BBC-20151026">{{cite news |author=Staff |title=Processed meats do cause cancer – WHO |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-34615621 |date=October 26, 2015 |work=] |access-date=October 26, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151026101723/http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-34615621 |archive-date=October 26, 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref>--> | |||

| ], ] (NHS) and the ] have stated that red and processed meat intake increases risk of ].<ref>. nhs.uk. Retrieved March 22, 2023.</ref><ref>. cancerresearchuk.org. Retrieved March 22, 2023.</ref><ref>. progressreport.cancer.gov. Retrieved March 22, 2023.</ref> The ] in their "Diet and Physical Activity Guideline", stated "evidence that red and processed meats increase cancer risk has existed for decades, and many health organizations recommend limiting or avoiding these foods."<ref>{{cite journal |title=American Cancer Society guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention |journal=CA |date=2020 |doi=10.3322/caac.21591 |last1=Rock |first1=Cheryl L. |last2=Thomson |first2=Cynthia |last3=Gansler |first3=Ted |last4=Gapstur |first4=Susan M. |last5=McCullough |first5=Marjorie L. |last6=Patel |first6=Alpa V. |last7=Andrews |first7=Kimberly S. |last8=Bandera |first8=Elisa V. |last9=Spees |first9=Colleen K. |last10=Robien |first10=Kimberly |last11=Hartman |first11=Sheri |last12=Sullivan |first12=Kristen |last13=Grant |first13=Barbara L. |last14=Hamilton |first14=Kathryn K. |last15=Kushi |first15=Lawrence H. |last16=Caan |first16=Bette J. |last17=Kibbe |first17=Debra |last18=Black |first18=Jessica Donze |last19=Wiedt |first19=Tracy L. |last20=McMahon |first20=Catherine |last21=Sloan |first21=Kirsten |last22=Doyle |first22=Colleen |display-authors=6 |volume=70 |issue=4 |pages=245–271 |pmid=32515498 |s2cid=219550658|doi-access=free }}</ref> The ] have stated that "eating red and processed meat increases cancer risk".<ref>. cancer.ca. Retrieved April 10, 2023.</ref> | |||

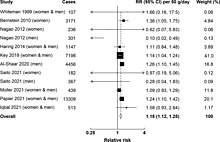

| A 2021 review found an increase of 11–51% risk of multiple cancer per 100g/d increment of red meat, and an increase of 8–72% risk of multiple cancer per 50g/d increment of processed meat.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Huang Y, Cao D, Chen Z, Chen B, Li J, Guo J, Dong Q, Liu L, Wei Q |title=Red and processed meat consumption and cancer outcomes: Umbrella review |journal=Food Chem |volume=356 |pages=129697 |date=September 2021 |pmid=33838606 |doi=10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129697 |type=Review}}</ref> | |||

| Cooking muscle meat creates ]s (HCAs), which are thought to increase cancer risk in humans. Researchers at the National Cancer Institute published results of a study which found that human subjects who ate beef rare or medium-rare had less than one third the risk of stomach cancer than those who ate beef medium-well or well-done.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Risk/heterocyclic-amines |title=National Cancer Institute – Heterocyclic Amines in Cooked Meats |publisher=Cancer.gov |date=September 15, 2004 |access-date=May 1, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101221034421/http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Risk/heterocyclic-amines |archive-date=December 21, 2010 |url-status=live }}</ref> While eating muscle meat raw may be the only way to avoid HCAs fully, the ] states that cooking meat below {{convert|212|F|C|order=flip}} creates "negligible amounts" of HCAs. ] meat before cooking may reduce HCAs by 90%.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Risk/heterocyclic-amines |title=Heterocyclic Amines in Cooked Meats – National Cancer Institute |publisher=Cancer.gov |date=September 15, 2004 |access-date=May 1, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101221034421/http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Risk/heterocyclic-amines |archive-date=December 21, 2010 |url-status=live }}</ref> ]s, present in processed and cooked foods, are carcinogenic, being linked to colon cancer. ]s, present in processed, smoked and cooked foods, are similarly carcinogenic.<ref name="PAHs">{{cite web|url=http://ec.europa.eu/food/fs/sc/scf/out154_en.pdf |title=PAH-Occurrence in Foods, Dietary Exposure and Health Effects |access-date=May 1, 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110519225348/http://ec.europa.eu/food/fs/sc/scf/out154_en.pdf |archive-date=May 19, 2011 }}</ref> | |||

| === Bacterial contamination === | |||

| Bacterial contamination has been seen with meat products. A 2011 study by the ] showed that nearly half (47%) of the meat and poultry in U.S. grocery stores were contaminated with '']'', with more than half (52%) of those bacteria resistant to antibiotics.<ref name="Staph">{{cite web|url=https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/04/110415083153.htm|title=US Meat and Poultry Is Widely Contaminated With Drug-Resistant Staph Bacteria|work=sciencedaily.com|access-date=March 9, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170707081303/https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/04/110415083153.htm|archive-date=July 7, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> A 2018 investigation by the ] and '']'' found that around 15 percent of the US population suffers from foodborne illnesses every year. The investigation highlighted unsanitary conditions in US-based meat plants, which included meat products covered in excrement and abscesses "filled with pus".<ref>{{cite news |last=Wasley |first=Andrew |date=February 21, 2018 |title='Dirty meat': Shocking hygiene failings discovered in US pig and chicken plants |url=https://www.theguardian.com/animals-farmed/2018/feb/21/dirty-meat-shocking-hygiene-failings-discovered-in-us-pig-and-chicken-plants |work=] |access-date=February 24, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180223222127/https://www.theguardian.com/animals-farmed/2018/feb/21/dirty-meat-shocking-hygiene-failings-discovered-in-us-pig-and-chicken-plants |archive-date=February 23, 2018 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Complete cooking and the careful avoidance of recontamination reduce the risk of bacterial infections from meat.<ref>{{cite journal |pmc=2518970 |title=Colonic protein fermentation and promotion of colon carcinogenesis by thermolyzed casein |last1=Corpet |first1=Denis |last2=Yin |first2=Y. |last3=Zhang |first3=X. |last4=Rémésy |first4=C. |last5=Stamp |first5=D. |last6=Medline |first6=A. |last7=Thompson |first7=L. |last8=Bruce |first8=W. |last9=Archer |first9=M. |display-authors=6 |year=1995 |pmid=7603887 |doi=10.1080/01635589509514381 |volume=23 |issue=3 |journal=Nutr Cancer |pages=271–281}}</ref> | |||

| === Diabetes === | |||

| Consumption of 100 g/day of red meat and 50 g/day of processed meat is associated with an increased risk of ].<ref name="Giosuè Calabrese Riccardi Vaccaro 2022">{{cite journal |last1=Giosuè |first1=Annalisa |last2=Calabrese |first2=Ilaria |last3=Riccardi |first3=Gabriele |last4=Vaccaro |first4=Olga |last5=Vitale |first5=Marilena |title=Consumption of different animal-based foods and risk of type 2 diabetes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective studies |journal=Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice |volume=191 |date=2022 |doi=10.1016/j.diabres.2022.110071 |page=110071|pmid=36067917 }}</ref> | |||

| ] advises people to limit their intake of red and processed meat.<ref>. diabetes.org.uk. Retrieved March 22, 2023.</ref><ref>. diabetes.org.uk. Retrieved March 22, 2023.</ref> | |||

| === Infectious diseases === | |||

| Meat production and trade substantially increase risks for infectious diseases (]), including ], whether though contact with wild and farmed animals, or via husbandry's environmental impact.<ref name="10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109341">{{cite journal |last1=González |first1=Neus |last2=Marquès |first2=Montse |last3=Nadal |first3=Martí |last4=Domingo |first4=José L. |title=Meat consumption: Which are the current global risks? A review of recent (2010–2020) evidences |journal=Food Research International |date=November 1, 2020 |volume=137 |pages=109341 |doi=10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109341 |pmid=33233049 |pmc=7256495 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Greger |first1=Michael |title=Primary Pandemic Prevention |journal=American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine |date=September 2021 |volume=15 |issue=5 |pages=498–505 |doi=10.1177/15598276211008134 |pmid=34646097 |pmc=8504329}}</ref> For example, ] from poultry meat production is a threat to human health.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sutton |first1=Troy C. |title=The Pandemic Threat of Emerging H5 and H7 Avian Influenza Viruses |journal=Viruses |date=September 2018 |volume=10 |issue=9 |pages=461 |doi=10.3390/v10090461 |pmid=30154345 |pmc=6164301 |doi-access=free }}</ref> Furthermore, the use of antibiotics in meat production contributes to ]<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Monger |first1=Xavier C. |last2=Gilbert |first2=Alex-An |last3=Saucier |first3=Linda |last4=Vincent |first4=Antony T. |title=Antibiotic Resistance: From Pig to Meat |journal=Antibiotics |date=October 2021 |volume=10 |issue=10 |pages=1209 |doi=10.3390/antibiotics10101209 |pmid=34680790 |pmc=8532907 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Clifford |first1=Katie |last2=Desai |first2=Darash |last3=Prazeres da Costa |first3=Clarissa |last4=Meyer |first4=Hannelore |last5=Klohe |first5=Katharina |last6=Winkler |first6=Andrea |last7=Rahman |first7=Tanvir |last8=Islam |first8=Taohidul |last9=Zaman |first9=Muhammad H |title=Antimicrobial resistance in livestock and poor quality veterinary medicines |journal=] |date=September 1, 2018 |volume=96 |issue=9 |pages=662–664 |doi=10.2471/BLT.18.209585 |doi-broken-date=December 5, 2024 |pmid=30262949 |pmc=6154060 }}</ref> – which contributes to millions of deaths<ref name=":8">{{Cite journal |last1=Murray |first1=Christopher JL |last2=Ikuta |first2=Kevin Shunji |last3=Sharara |first3=Fablina |last4=Swetschinski |first4=Lucien |last5=Aguilar |first5=Gisela Robles |last6=Gray |first6=Authia |last7=Han |first7=Chieh |last8=Bisignano |first8=Catherine |last9=Rao |first9=Puja |last10=Wool |first10=Eve |last11=Johnson |first11=Sarah C. |display-authors=6 |date=January 19, 2022 |title=Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis |journal=] |volume=399 |issue=10325 |pages=629–655 glish |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0 |pmid=35065702 |pmc=8841637 |s2cid=246077406}}</ref> – and makes it harder to control infectious diseases.<!--<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Greger |first1=Michael |date=September 2021 |title=Primary Pandemic Prevention |journal=American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine |volume=15 |issue=5 |pages=498–505 |doi=10.1177/15598276211008134 |pmc=8504329 |pmid=34646097 |s2cid=235503730}}</ref>--><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Walker |first1=Polly |last2=Rhubart-Berg |first2=Pamela |last3=McKenzie |first3=Shawn |last4=Kelling |first4=Kristin |last5=Lawrence |first5=Robert S. |date=June 2005 |title=Public health implications of meat production and consumption |journal=Public Health Nutrition |volume=8 |issue=4 |pages=348–356 |doi=10.1079/PHN2005727 |pmid=15975179 |s2cid=59196 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hafez |first1=Hafez M. |last2=Attia |first2=Youssef A. |date=2020 |title=Challenges to the Poultry Industry: Current Perspectives and Strategic Future After the COVID-19 Outbreak |journal=] |volume=7 |page=516 |doi=10.3389/fvets.2020.00516 |pmc=7479178 |pmid=33005639 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Mehdi |first1=Youcef |last2=Létourneau-Montminy |first2=Marie-Pierre |last3=Gaucher |first3=Marie-Lou |last4=Chorfi |first4=Younes |last5=Suresh |first5=Gayatri |last6=Rouissi |first6=Tarek |last7=Brar |first7=Satinder Kaur |last8=Côté |first8=Caroline |last9=Ramirez |first9=Antonio Avalos |last10=Godbout |first10=Stéphane |display-authors=6 |date=June 1, 2018 |title=Use of antibiotics in broiler production: Global impacts and alternatives |journal=Animal Nutrition |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=170–178 |doi=10.1016/j.aninu.2018.03.002 |pmc=6103476 |pmid=30140756}}</ref> | |||

| === Changes in consumer behavior === | |||

| In response to changing ]s as well as health concerns about ], consumers have altered their consumption of various meats. Consumption of beef in the United States between 1970 and 1974 and 1990–1994 dropped by 21%, while consumption of ] increased by 90%.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/foodreview/jan1996/frjan96f.pdf |title=Archived copy |access-date=August 17, 2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060304100230/http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/foodreview/jan1996/frjan96f.pdf |archive-date=March 4, 2006 }}</ref> | |||

| === Heart disease === | |||

| ] | |||

| Except for poultry, at 50 g/day unprocessed red and processed meat are risk factors for ischemic heart disease, increasing the risk by about 9 and 18% respectively.<ref name="10.1080/10408398.2021.1949575"/><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Zhang |first1=X. |display-authors=etal |year=2022 |title=Red/processed meat consumption and non-cancer-related outcomes in humans: umbrella review |journal=British Journal of Nutrition|volume=22 |issue=3 |pages=484–494 |doi=10.1017/S0007114522003415 |pmid=36545687 |s2cid=255021441 }}</ref> | |||

| == Environmental impact == | |||

| {{further|Environmental impacts of animal agriculture}} | |||

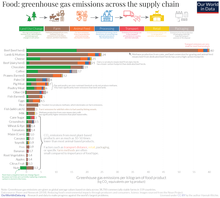

| A multitude of serious negative environmental effects are associated with meat production. Among these are greenhouse gas emissions, ] use, water use, water quality changes, and effects on grazed ecosystems. They are so significant that according to ] researchers, "a ] diet is probably the single biggest way to reduce your impact on planet Earth... far bigger than cutting down on your flights or buying an electric car".<ref>{{cite news |last1=Petter |first1=Olivia |title=Veganism is 'single biggest way' to reduce our environmental impact, study finds |url=https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/veganism-environmental-impact-planet-reduced-plant-based-diet-humans-study-a8378631.html |work=The Independent |date=September 24, 2020 |access-date=23 November 2023}}</ref> However, this is often ignored in the public consciousness and in plans to tackle serious environmental issues such as the ].<ref>{{cite news |last1=Dalton |first1=Jane |title=World leaders 'reckless for ignoring how meat and dairy accelerate climate crisis' |url=https://www.independent.co.uk/climate-change/news/climate-meat-dairy-diet-food-co2-b1951760.html |newspaper=] |access-date=23 November 2023}}</ref> | |||