| Revision as of 20:57, 8 May 2008 editBistiks (talk | contribs)66 edits The picture shows the University, that's what the section is mainly about.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:26, 10 January 2025 edit undo2a02:3100:5936:5700:352a:45b:a9dd:3315 (talk) Short description regarding Kabul: de facto it is part of Taliban's Islamic Emirate, however de jure it is part of the Islamic Republic recognised internationally by the United Nations. Please leave the article how it currently is written. Thanks!Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Capital and the largest city of Afghanistan}} | |||

| {{otherplaces}} | |||

| {{Other places}} | |||

| {{Infobox City in Afghanistan | |||

| {{Pp-move}} | |||

| | official_name =Kabul | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=September 2024}} | |||

| | native_name =کابل | |||

| {{Infobox settlement | |||

| | province_name =Kabul | |||

| <!--See the Table at Infobox settlement for all fields and descriptions of usage--> | |||

| | image =Mountains of Kabul.jpg | |||

| <!-- Basic info ---------------->| name = Kabul | |||

| | image_size = 275px | |||

| | native_name = {{lang|fa|کابل}} | |||

| | image_caption = Kabul City | |||

| | settlement_type = ] | |||

| | latd = 34.533 | |||

| <!-- images and maps ----------->| image_skyline = {{Photomontage | |||

| | longd = 69.166 | |||

| | photo1a = Kabul, Afghanistan view.jpg | |||

| | districts = 18 ] or ]s | |||

| | photo2a = 200229-D-AP390-1529 (49603221753).jpg | |||

| | population_total = 2994000| population_as_of = 2005 | |||

| | photo2b = Shah-e-Doshamshera Mosque - panoramio.jpg | |||

| | population_footnote =<ref>UN World Urbanization Prospects: | |||

| | photo3a = Sakhi mosque, Kabul.jpg | |||

| The 2005 Revision Population Database...</ref> | |||

| | photo3b = Modern Kabul - panoramio.jpg | |||

| | population_note = UN estimate of city proper | |||

| | photo4a = Kabul Afghanistan, place where I live.jpg | |||

| | population_metro = | |||

| | photo4b = | |||

| | population_metro_as_of = | |||

| | photo5a = | |||

| | population_rank = 1st | |||

| | photo5b = | |||

| | population_density_km2 = | |||

| | color = white | |||

| | area_total_km2 = | |||

| | color_border = white | |||

| | elevation_m = 1790 | |||

| | position = center | |||

| | numdistricts = | |||

| | spacing = 2 | |||

| | leader_title = ] | |||

| | size = 266 | |||

| | leader_name = Rohullah Aman | |||

| | foot_montage = | |||

| | leader_title_2 = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | leader_name_2 = Asmatullah Dawlatzai <ref>Pajhwok Afghan News, </ref> | |||

| | image_caption = <div style="background:#FEE8AB;"> '''Left-to-right from top:'''<br />Skyline in 2020, the ], ], ], modern Kabul, skyline in 2021 </div> | |||

| | image_flag = <!--Flag of Kabul.svg is no longer the flag of the city. Currently there is no flag of Kabul. So please do not add it here.--> | |||

| | image_seal = Kabul Municipality logo.png | |||

| | image_shield = | |||

| | image_map = | |||

| | map_caption = | |||

| | pushpin_map = Afghanistan#Asia | |||

| | pushpin_label_position = right | |||

| | pushpin_mapsize = 300 | |||

| | pushpin_map_caption = | |||

| | pushpin_relief = yes | |||

| | coordinates = {{Coord|34|31|31|N|69|10|42|E|region:AF-KAB_type:city(4600000)|display=inline,title}} | |||

| | motto = | |||

| | nickname = ] of ]<ref name="Golden" /><ref name="Glory" /> | |||

| | subdivision_type = Country | |||

| | subdivision_name = {{flag|Islamic Republic of Afghanistan|name=Afghanistan}} | |||

| | subdivision_type1 = ] | |||

| | subdivision_name1 = {{flagicon image|Kabul Municipality logo.png}} ] | |||

| | subdivision_type2 = No. of districts | |||

| | subdivision_name2 = 22 | |||

| | subdivision_type3 = No. of Gozars | |||

| | subdivision_name3 = 630 | |||

| | established_title = Capital formation | |||

| | established_date = 1776<ref name="Stanford" /> | |||

| | government_type = ] | |||

| <!-- Politics ----------------->| government_footnotes = | |||

| | leader_title = ] | |||

| | leader_name = ] | |||

| | leader_title2 = ] | |||

| | leader_name2 = ] Abdul Rashid<ref name="bakhtarnews">{{cite web |url=https://bakhtarnews.af/ps/د-اسلامي-امارت-په-تشکیلاتو-کې-نوي-کسان-پ/ |title=د اسلامي امارت په تشکیلاتو کې نوي کسان پر دندو وګومارل شول |date=4 October 2021 |website=باختر خبری آژانس |access-date=22 November 2021 |archive-date=16 November 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211116104819/https://bakhtarnews.af/ps/%d8%af-%d8%a7%d8%b3%d9%84%d8%a7%d9%85%d9%8a-%d8%a7%d9%85%d8%a7%d8%b1%d8%aa-%d9%be%d9%87-%d8%aa%d8%b4%da%a9%db%8c%d9%84%d8%a7%d8%aa%d9%88-%da%a9%db%90-%d9%86%d9%88%d9%8a-%da%a9%d8%b3%d8%a7%d9%86-%d9%be/ |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| <!-- Area --------------------->| area_footnotes = | |||

| | area_total_km2 = 1028.24 <!-- ALL fields dealing with a measurements are subject to automatic unit conversion--> | |||

| | area_land_km2 = 1028.24<!--See table @ Template:Infobox Settlement for details on automatic unit conversion--> | |||

| | area_water_km2 = 0 | |||

| | elevation_footnotes = <!--for references: use<ref></ref> tags--> | |||

| | elevation_m = 1791 | |||

| <!-- Population ------------>| population_footnotes = | |||

| | population_total = 4.72 million | |||

| | population_as_of = 2024 | |||

| | population_density_km2 = 6749.39702793 | |||

| | population_urban = | |||

| | population_note = | |||

| | population_demonyms = Kabuli | |||

| <!-- General information --------------->| timezone = ] | |||

| | utc_offset = +04:30 | |||

| | timezone_DST = (Not Observed) | |||

| | postal_code_type = Postal code | |||

| | postal_code = 10XX | |||

| | area_code = ] | |||

| | blank_name = ] | |||

| | blank_info = ] | |||

| | website = {{URL|km.gov.af/}} | |||

| | official_name = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| <!--Infobox ends--> | |||

| '''Kābul''' ({{PerB|کابل}}, ]: ) is the ] and largest city of ], with an estimated population of approximately three million. It is an economic and cultural centre, situated 5,900 ] (1,800 m) above-sea-level in a narrow valley, wedged between the ] mountains along the ]. Kabul is linked with ], ], ] and ] via a long ] (circular highway) that stretches across the country. It is also linked by highways with ] to the southeast and ] to the north. | |||

| '''Kabul'''{{Efn| | |||

| Kabul's main products include ]s, ], ], and ], but, since 1978, a state of nearly continuous war has limited the economic productivity of the city. | |||

| * Pronounced {{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|ɑː|b|uː|l}},<ref>], 1969.</ref> {{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|ɑː|b|əl}},<ref>{{Cite Merriam-Webster|Kabul|accessdate=22 November 2021}}</ref> {{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|ɑː|b|ʊ|l|,_|k|ə|ˈ|b|uː|l}},<ref>{{cite web|title=American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language|url=https://ahdictionary.com/word/search.html?q=kabul|accessdate=1 April 2024|archive-date=1 April 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240401032515/https://ahdictionary.com/word/search.html?q=kabul|url-status=live}}</ref> {{IPAc-en|k|ə|ˈ|b|ʊ|l}}{{citation needed|date=February 2024}} | |||

| * {{langx|ps|کابل|Kâbəl}}, {{IPA|ps|kɑˈbəl|IPA}}{{citation needed|date=February 2024}} | |||

| * {{langx|prs|کابل|Kābul}}, {{IPA|fa|kɑːˈbʊl|IPA}}{{citation needed|date=February 2024}} | |||

| }} is the capital city of ]. Located in the eastern half of the country, it is also a municipality, forming part of the ]. The city is divided for administration into ]. In 2025 its population is estimated to be 6.74 million people. In contemporary times, Kabul has served as Afghanistan's political, cultural and economical center.<ref>{{cite book |first=Fabrizio |last=Foschini |date=April 2017 |title=Kabul and the challenge of dwindling foreign aid |url=https://ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/resources/docs/USIP-pw126_kabul-and-the-challenge-of-dwindling-foreign-aid.pdf |archive-date=9 June 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200609180040/https://ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/resources/docs/USIP-pw126_kabul-and-the-challenge-of-dwindling-foreign-aid.pdf |url-status=live |series=Peaceworks no. 126 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-60127-641-4 |via=] |access-date=1 June 2021}}</ref> Rapid urbanisation has made it the country's ] and the ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.citymayors.com/statistics/largest-cities-mayors-1.html |title=Largest cities in the world and their mayors – 1 to 150 |publisher=City Mayors |date=17 May 2012 |access-date=17 August 2012 |archive-date=2 September 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110902093141/http://www.citymayors.com/statistics/largest-cities-mayors-1.html |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The modern-day city of Kabul is located high in a narrow ] in the ] mountain range, and is bounded by the ]. At an elevation of {{convert|1790|m|ft|0}}, it is one of the ]. The center of the city contains its old neighborhoods, including the areas of Khashti Bridge, Khabgah, Kahforoshi, Deh-Afghanan, Chandavel, Shorbazar, Saraji and Baghe Alimardan.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Kabul | title=Kabul | History, Culture, Map, & Facts | Britannica | date=28 June 2023 | access-date=27 June 2023 | archive-date=27 August 2021 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210827201157/https://www.britannica.com/place/Kabul | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Kabul is over 3,000 years old. Many empires have long fought over the city, due to its strategic location along the trade routes of ] and ]. In 1504, ] captured Kabul and used it as his ] until 1526, before his conquest of India. In 1776, ] made it the capital of modern Afghanistan.<ref>Britannica Concise Encyclopedia - ''Kabul''...</ref> The population of the city is predominantly ].<ref name=Encarta/><ref> "Kabul." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 17 Feb. 2008 <http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9044257>.</ref> | |||

| Kabul is said to be over 3,500 years old, and was mentioned at the time of the ]. Located at a crossroads in ]—roughly halfway between ], in the west and ], in the east—the city is situated in a strategic location along the trade routes of ] and ]. It was a key destination on the ancient ]<ref>{{cite web |url=https://thediplomat.com/2017/11/afghanistan-the-heart-of-silk-road-in-asia/ |title=Afghanistan: The Heart of Silk Road in Asia |website=] |access-date=26 November 2019 |archive-date=9 June 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200609174051/https://thediplomat.com/2017/11/afghanistan-the-heart-of-silk-road-in-asia/ |url-status=live}}</ref> and was traditionally seen as the meeting point between ], ] and ].<ref name="undermughal">{{cite journal |first=Farah |last=Samrin |title=The City of Kabul Under the Mughals |journal=Proceedings of the Indian History Congress |year=2005 |volume=66 |pages=1307 |jstor=44145943 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/44145943 |access-date=29 June 2021 |archive-date=29 June 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210629170711/https://www.jstor.org/stable/44145943 |url-status=live }}</ref> Over the centuries Kabul has been under the rule of various dynasties and empires, including the ], ], ], the ], the ], ], the ], the ], the ], the ], the ] and the Arman Rayamajhis. | |||

| == History == | |||

| The city of Kabul is thought to have been established between 2000 ] and 1500 BCE.<ref>''The history of Afghanistan'', </ref> In the ] (composed between 1700–1100 BCE) the word "''Kubhā''" is mentioned, which appears to refer to the ]. There is a reference to a settlement called Kabura by the ] ] around 400 BCE{{Fact|date=January 2008}} which may be the basis for the use of the name Kabura by ].<ref>] conquered Kabul during his conquest of the Persian Empire. The city later became part of the ] before becoming part of the ]. The ]ns founded the town of ] near Kabul, but it was later ceded to the Mauryans in the 1st century BCE. ] Kingdoms in 565 BCE.]] | |||

| In the 16th century, the ] used Kabul as a summer capital, during which time it prospered and increased in significance.<ref name="undermughal" /> It briefly came under the control of the ] following ], until finally coming under local rule by the ] in 1747.<ref name="Dupree">{{cite web |url=http://www.aisk.org/aisk/NHDAHGTK05.php |title=An Historical Guide to Kabul – The Story of Kabul |author=] / Aḥmad ʻAlī Kuhzād |publisher=American International School of Kabul |year=1972 |access-date=18 September 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100830031416/http://www.aisk.org/aisk/NHDAHGTK05.php |archive-date=30 August 2010}}</ref> Kabul became the capital of Afghanistan in 1776 during the reign of ] (a son of ]).<ref name="Stanford" /> In the 19th century the city was occupied by the ]: after establishing foreign relations and agreements, they withdrew from ] and returned to ]. | |||

| According to many noted scholars, the ] name of Kabul is ].<ref> Ethnologische Forschungen und Sammlung von Material für dieselben, 1871, p 244, Adolf Bastian - Ethnology.</ref> <ref>The People of India: A Series of Photographic Illustrations, with ..., 1868, p 155, John William Kaye, Meadows Taylor, Great Britain India Office - Ethnology.</ref> <ref>Supplementary Glossary, p. 304, H. M. Elliot.</ref> <ref> Various Census of India, 1867, p 34.</ref> It is mentioned as ''Kophes'' or ''Kophene'' in the ] writings. ''Gazetteer of Bombay Presidency 1904'' maintains that the ancient name of Kabul was ''Kambojapura'', which ] (160 ]) mentions as ''Kaboura'' (from ''Ka(m)bo(j)pura?''). ] refers to the name as ''Kaofu'', which according to Dr. J. W. McCrindle <ref>Alexander’s Invasion, p 38, J. W. McCrindle; Megasthenes and Arrian, p 180, J. W. McCrindle.</ref>, Dr Sylvain Lévi <ref> Pre-Aryan and Pre-Dravidian in India, 1993 edition, p 100, Dr Sylvain Lévi, Jules Bloch, Jean Przyluski, Asian Educational Services - Indo-Aryan philology.</ref>, Dr. B. C. Law <ref> Some Kṣatriya Tribes of Ancient India, 1924, p 235, Dr B. C. Law - Kshatriyas; Indological Studies, 1950, p 36; Tribes in Ancient India, 1943, p 3.</ref>, Dr. R. K. Mukkerji <ref> Chandragupta Maurya and His Times, 1966, p 173, Dr Radhakumud Mookerji - History; Studies in Ancient Hindu Polity: Based on the Arthaṡâstra of Kautilya, 1914, p 40, Narendra Nath Law, Kauṭalya, Radhakumud Mookerji; The Fundamental Unity of India, 2004, p 86; The Fundamental Unity of India (from Hindu Sources), 1914, p 57, Dr Radhakumud Mookerji.</ref>, N. L. Dey <ref>Geographical Dictionary of ancient and Medieval India, Dr Nundo Lal Dey.</ref> and many other scholars <ref> The Modern Review, 1907, p 135, Ramananda Chatterjee - India; Literary History of Ancient India in Relation to Its Racial and Linguistic ..., p 165, Chandra Chakraberty; Prācīna Kamboja, jana aura janapada =: Ancient Kamboja, people and country, 1981, Dr Jiyālāla Kāmboja, Dr Satyavrat Śāstrī - Kamboja (Pakistan) etc.</ref>, is equivalent to ] ] (''Kamboj/Kambuj''). ''Kaofu'' was also the ] of one of the five tribes of the ] who had migrated from across the ] into Kabul valley around ] era <ref>The Ancient Geography of India, p 15, A Cunningham.</ref>. According to some scholars, the fifth clan mentioned among the Tochari/Yuechi may have been a clan of the ] <ref>Ancient Kamboja, People and the Country, 1981, p 43, Dr J. L. Kamboj.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Kabul is known for its historical gardens, ]s, and palaces<ref>{{cite news |last1=Gopalakrishnan |first1=Raju |title=Once called paradise, now Kabul struggles to cope |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-afghanistan-capital/once-called-paradise-now-kabul-struggles-to-cope-idUSSP20888220070416 |publisher=Reuters |date=16 April 2007 |access-date=1 June 2021 |archive-date=8 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210308151538/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-afghanistan-capital/once-called-paradise-now-kabul-struggles-to-cope-idUSSP20888220070416 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author1=Abdul Zuhoor Qayomi |title=Kabul City: Isn't just capital of Afghanistan but of palaces as well – Afghanistan Times |url=http://www.afghanistantimes.af/kabul-city-isnt-just-capital-of-afghanistan-but-of-palaces-as-well/ |website=Afghanistan Times |access-date=1 June 2021 |archive-date=15 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210515194006/http://www.afghanistantimes.af/kabul-city-isnt-just-capital-of-afghanistan-but-of-palaces-as-well/ |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author1=Sayed A Azimi |title=Reversing Kabul's Environmental Setbacks |url=https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/reversing-kabuls-environmental-setbacks-sayed-aziz-azimi |publisher=LinkedIn |language=en |access-date=1 June 2021 |archive-date=8 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210808095807/https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/reversing-kabuls-environmental-setbacks-sayed-aziz-azimi |url-status=live}}</ref> such as the ], ] and the ]. In the second half of the 20th century, the city became a stop on the ] undertaken by many ]ans<ref name="overthrown" /><ref>''Dateline Mongolia: An American Journalist in Nomad's Land'' by Michael Kohn</ref><ref>{{cite web |title='Mein Kabul': ORF-Reporterlegende Fritz Orter präsentiert im 'Weltjournal' 'seine Stadt' – am 31. August um 22.30 Uhr in ORF 2 |url=https://www.ots.at/presseaussendung/OTS_20160830_OTS0058/mein-kabul-orf-reporterlegende-fritz-orter-praesentiert-im-weltjournal-seine-stadt-am-31-august-um-2230-uhr-in-orf-2 |publisher=OTS.at |language=de |access-date=1 June 2021 |archive-date=9 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210809200243/https://www.ots.at/presseaussendung/OTS_20160830_OTS0058/mein-kabul-orf-reporterlegende-fritz-orter-praesentiert-im-weltjournal-seine-stadt-am-31-august-um-2230-uhr-in-orf-2 |url-status=live}}</ref> and gained the nickname "] of Central Asia".<ref name="Golden">{{Cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/18/weekinreview/18bumiller.html |title=Remembering Afghanistan's Golden Age |newspaper=The New York Times |date=17 October 2009 |last1=Bumiller |first1=Elisabeth |access-date=24 August 2021 |archive-date=24 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210824111805/https://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/18/weekinreview/18bumiller.html |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Glory">{{Cite news |url=https://gandhara.rferl.org/a/kabul-glory-days-kabulis-history-afghanistan/31011399.html |title=Kabul Residents, Visitors Recall Capital's Golden Era Before Conflict |newspaper=Radiofreeeurope/Radioliberty |publisher=RFE/RL |access-date=24 August 2021 |archive-date=24 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210824160030/https://gandhara.rferl.org/a/kabul-glory-days-kabulis-history-afghanistan/31011399.html |url-status=live |last1=Kohzad |first1=Nilly }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://centralasiainstitute.org/in-wake-of-taliban-peace-talks-afghan-women-hope-basic-human-rights-still-theirs/ |title=Taliban Peace Talks in Afghanistan |date=28 May 2019 |access-date=24 August 2021 |archive-date=24 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210824160028/https://centralasiainstitute.org/in-wake-of-taliban-peace-talks-afghan-women-hope-basic-human-rights-still-theirs/ |url-status=live}}</ref> This period of tranquility ended in 1978 with the ], and the subsequent ] in 1979 which sparked a 10-year ]. The 1990s were marked by ] between splinter factions of the disbanded ] which destroyed much of the city.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.lonelyplanet.com/afghanistan/kabul/history |title=History of Kabul |publisher=] |access-date=27 May 2013 |archive-date=3 April 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190403060121/https://www.lonelyplanet.com/afghanistan/kabul/history |url-status=live}}</ref> In 1996, ] after four years of ] fighting. The ] after the ] which followed the ] in the US in 2001. In 2021, ] following the ]. | |||

| The ] captured Kabul from the Mauryans in the early 2nd century BCE, then lost the city to their subordinates in the ] in the mid 2nd century BCE. ] expelled the Indo-Greeks by the mid 1st century BCE, but lost the city to the ] nearly 100 years later. It was conquered by Kushan Emperor ] in the early 1st century CE and remained Kushan territory until at least the 3rd century CE.<ref> Hill, John E. 2004. ''The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu.'' Draft annotated English translation...</ref><ref> Hill, John E. 2004. ''The Peoples of the West from the Weilue'' 魏略 ''by Yu Huan'' 魚豢'': A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE.'' Draft annotated English translation... </ref> Kabul was one of the two capital cities of Kushans. | |||

| ==Toponymy and etymology== | |||

| Around 230 CE the Kushans were defeated by the ] and were replaced by Sassanid vassals known as the ] or ]. In 420 CE the ] (Kushan kings) were driven out of Afghanistan by the ] tribe known as the ], who were then replaced in the 460s by the ]. The Hephthalites were defeated in 565 CE by a coalition of Persian and Turkish armies, and most of the realm fell to those Empires. Kabul became part of the surviving ] Kingdom of ], who were also known as Kabul-Shahan. The rulers of Kabul-Shahan built a huge defensive wall around the city to protect it from invaders. This wall has survived until today and is considered a historical site. Around 670 CE the Kushano-Hephthalites were replaced by the ] or ]-Shahi dynasty. | |||

| Kabul is also spelled as '''Cabool''', '''Cabol''', '''Kabol''', or '''Cabul'''.{{citation needed|date=February 2024}} | |||

| Kabul was known by different names throughout its history.<ref name="OxfordModern">{{cite encyclopedia |last=Kakar |first=M. Hassan |editor-last=Stearns |editor-first=Peter N. |title=Kabul |year=2008 |encyclopedia=Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern World |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-517632-2 |url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195176322.001.0001/acref-9780195176322-e-840?rskey=6DESxq&result=6 |access-date=13 February 2021 |archive-date=3 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210503085215/https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195176322.001.0001/acref-9780195176322-e-840?rskey=6DESxq&result=6 |url-status=live}}</ref> Its meaning is unknown, but "certainly pre-dates the advent of Islam when it was an important centre on the route between ] and the ]".<ref name="OxfordPlaceNames">{{cite encyclopedia |editor-last=Everett-Heath |editor-first=John |title=Kabul |year=2020 |encyclopedia=Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Place Names |edition=6 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-190563-6 |url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191905636.001.0001/acref-9780191905636-e-3372?rskey=wE0hco&result=1 |access-date=13 February 2021 |archive-date=3 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210503085109/https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191905636.001.0001/acref-9780191905636-e-3372?rskey=wE0hco&result=1 |url-status=live}}</ref> In ], it was known as ''Kubha'', whereas Greek authors of ] referred to it as ''Kophen'', ''Kophes'' or ''Koa''.<ref name="OxfordModern" /> The Chinese traveler ] (fl. 7th century CE) recorded the city as ''Koafu'' (高附).<ref name="OxfordModern" /> The name "Kabul" was first applied to the ] before being applied to the area situated between the ] and ] (present-day ]).<ref name="OxfordModern" /><ref name="OxfordPlaceNames" /> This area was also known as ].<ref name="OxfordModern" /> ] (died 1893) noted in the 19th century that ''Kaofu,'' as recorded by the Chinese was in all likelihood the name of "one of the five Yuchi or Tukhari tribes".<ref name="OxfordModern" /> Cunningam added that this tribe gave its name to the city after it was occupied by them in the 2nd century BCE.<ref name="OxfordModern" /> This "supposition seems likely" as the Afghan historian ] (1898–1978) wrote that in the ] (sacred book of ]), Kabul was known as ''Vaekereta'', whereas the Greeks of antiquity referred to it as ''Ortospana'' ("High Place"), which corresponds to the Sanskrit word ''Urddhastana'', which was applied to Kabul.<ref name="OxfordModern" /> The Greek geographer ] (died {{circa|170 CE}}) recorded Kabul as Καβουρα (''Kabura'').<ref name="OxfordModern" /> | |||

| ===Islamic conquest=== | |||

| In 674, the ] reached modern-day Afghanistan and occupied Kabul. However, it was not until the 9th century when ], a coppersmith turned ruler, established ] in ]. Over the remaining centuries to come the city was successively controlled by the ], ], ], ], ], ], and finally by the ]s. | |||

| According to a legend, one could find a lake in Kabul, in the middle of which the so-called "Island of Happiness" could be found, where a joyous family of musicians lived.<ref name="OxfordModern" /> According to this same legend, the island became accessible by the order of a king through the construction of a bridge (i.e. "pul" in Persian) made out of straw (i.e. "kah" in Persian).<ref name="OxfordModern" /> According to this legend the name Kabul was thus formed as a result of these two words combined, i.e. ''kah'' + ''pul''.<ref name="OxfordModern" /> The ''Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Place Names'' argues that the "suggestion that the name is derived from the ] root ''qbl'' 'meeting' or 'receiving' is unlikely".<ref name="OxfordPlaceNames" /> | |||

| In the 13th century the ] horde passed through. In the 14th century, Kabul rose again as a trading center under the kingdom of ] (''Tamerlane''), who married the sister of Kabul's ruler at the time. But as Timurid power waned, the city was captured in 1504 by ] and made into his headquarters. ], an ]n poet who visited at the time wrote "Dine and drink in Kabul: it is mountain, desert, city, river and all else." | |||

| It remains unknown when the name "Kabul" was first applied to the city.<ref name="OxfordModern" /> It "came into prominence" following the destruction of ] and other cities in what is present-day Afghanistan by ] (c. 1162–1227) in the thirteenth century.<ref name="OxfordModern" /> The centrality of the city within the region, as well as its cultural importance as a nexus of ethnic groups in the region, caused Kabul to become known as the Paris of Central Asia in the late 20th century. | |||

| ===Modern history=== | |||

| ] of Persia captured the city in 1738 but was assassinated nine years later. ], an Afghan military commander and personal bodyguard of Nader, took the throne in 1747, asserted ] rule and further expanded his new ]. His son ], after inheriting power, transferred the capital of Afghanistan from ] to Kabul in 1776.<ref>Encyclopaedia Britannica - ''The Durrani dynasty (from Afghanistan)''...</ref> Timur Shah died in 1793 and was succeeded by his son ]. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| In 1826, the kingdom was claimed by ] and taken from him by the ] in 1839 (see ]), who installed the unpopular puppet ]. An 1841 local uprising resulted in the loss of the British mission and the subsequent ] of approximately 16,000 people, which included civilians and ]s on their retreat from Kabul to ]. In 1842 the British returned, plundering ] in revenge before retreating back to ]. Dost Mohammed returned to the throne. | |||

| {{see also|Timeline of Kabul}} | |||

| ===Antiquity=== | |||

| The British invaded in 1878 as Kabul was under ]'s rule, but the British residents were again massacred. The invaders again came in 1879 under ], partially destroying Bala Hissar before retreating to India. ] was left in control of the country. ] | |||

| {{Cleanup|subsection|reason=chaotic structure, contradicting information, etc.|date=January 2018}} | |||

| The origin of Kabul, who built it and when, is largely unknown.<ref name="Adamec">Adamec, p.231</ref> The Hindu ], composed between 2000 and 1500 BC and one of the four canonical texts of ], and the Avesta, the primary canon of texts of Zoroastrianism, refer to the ] and to a settlement called ''Kubha''.<ref name="Adamec" /><ref name="Dupree-name">{{cite web |url=http://www.aisk.org/aisk/NHDAHGTK05.php |title=An Historical Guide to Kabul – The Name |author=Nancy Hatch Dupree / Aḥmad ʻAlī Kuhzād |publisher=American International School of Kabul |year=1972 |access-date=18 September 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100830031416/http://www.aisk.org/aisk/NHDAHGTK05.php |archive-date=30 August 2010}}</ref> | |||

| In the early 20th century, King ] rose to power. His reforms included electricity for the city and schooling for girls. He drove a ], and lived in the famous ]. In 1919, after the Third Anglo-Afghan War, Amanullah announced Afghanistan's independence from ] at ]. In 1929, Ammanullah Khan left Kabul due to a local uprise and his brother ] took control. King Nader Khan was assassinated in 1933 and his 19 year-old son, ], became the long lasting ]. | |||

| The Kabul valley was part of the ] (c. 678–549 BC).<ref>{{cite book |first=Graciana |last=del Castillo |author1-link=Graciana del Castillo |title=Guilty Party: The International Community in Afghanistan |publisher=Xlibris Corporation |isbn=978-1-4931-8570-2 |page=28 |date=2 April 2014}}</ref> In 549 BC, the Median Empire was annexed by ] and Kabul became part the ] (c. 550–330 BC).<ref>{{cite book |first1=Hafizullah |last1=Emadi |title=Culture and Customs of Afghanistan |publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group |isbn=978-0-313-33089-6 |page=26 |year=2005}}</ref> During that period, Kabul became a center of learning for Zoroastrianism, followed by ] and ].<ref>{{cite book |first1=Peter |last1=Marsden |title=The Taliban: War, Religion and the New Order in Afghanistan |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |isbn=978-1-85649-522-6 |page= |date=15 September 1998 |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/talibanwarreligi0000mars/page/12}}</ref> An inscription on ]'s tombstone lists Kabul as one of the 29 countries of the Achaemenid Empire.<ref name="Dupree-name" /> | |||

| ] opened for classes in early 1930s, and in 1940s, the city began to grow as an industrial center. The streets of the city began being paved in the 1950s. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In the 1960s, Kabul developed a cosmopolitan mood. The first ] store in ] was built there. ] was inaugurated in 1967, which was maintained with the help of visiting ] ]. | |||

| When ] annexed the Achaemenid Empire, the Kabul region came under his control.<ref>{{cite book |first1=Trudy |last1=Ring |title=International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania |year=1994 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-1-884964-04-6}}</ref> After his death, his empire was seized by his general ], becoming part of the ]. In 305 BC, the Seleucid Empire was extended to the ] which led to friction with the neighbouring ].<ref>{{cite book |first1=Meredith L. |last1=Runion |title=The History of Afghanistan |year=2007 |url=https://archive.org/details/historyafghanist00runi_653 |url-access=limited |publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group |isbn=978-0-313-33798-7 |page=}}</ref> | |||

| In 1969, a religious uprising at the ] protested the Soviet Union's increasing influence over Afghan politics and ]. This protest ended in the arrest of many of its organizers including ], a popular Islamic scholar. | |||

| During the Mauryan period, trade flourished because of uniform weights and measures. Irrigation facilities for public use were developed leading to an increased harvest of crops. People were also employed as artisans, jewelers, and carpenters.<ref>Romano, p.12</ref> | |||

| In July 1973, Zahir Shah was ousted in a bloodless coup and Kabul became the capital of a republic under ], the new President. ] | |||

| The ] took control of Kabul from the Mauryans in the early 2nd century BC, then lost the city to their successors in the ] around the mid-2nd century BC. Buddhism was greatly patronised by these rulers and the majority of people of the city were adherents of the religion.<ref>{{cite book |first1=John |last1=Snelling |title=The Buddhist Handbook: A Complete Guide to Buddhist Teaching and Practice |date=31 August 2011 |publisher=Random House |isbn=978-1-4464-8958-1}}</ref> ] expelled the Indo-Greeks by the mid 1st century BC, but lost the city to the ] about 100 years later.<ref name="Houtsma">{{Cite book |title=E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936 |last1=Houtsma |first1=Martijn Theodoor |volume=2 |year=1987 |publisher=BRILL |isbn=978-90-04-08265-6 |page=159 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zJU3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA159 |access-date=23 August 2010 |archive-date=3 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210503085005/https://books.google.com/books?id=zJU3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA159 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |first1=Louis |last1=Dupree |title=Afghanistan |publisher=Princeton University Press |isbn=978-1-4008-5891-0 |page=299 |date=14 July 2014}}</ref> | |||

| In 1975 an east-west electric trolley-bus system provided public transportation across the city. The system was built with assistance from ]. | |||

| ] statue at the ], early 1st millennium]] | |||

| After the ], on ], ], the ] occupied the capital. They turned the city into their command center during the 10-year conflict between the Soviet-allied government and the ] rebels. The American ] in Kabul closed on ], ]. The city fell into the hands of local ]s after the 1992 collapse of ]'s pro-communist government. As these forces divided into warring factions, the city increasingly suffered. In December, the last of the 86 city trolley buses came to a halt due to the conflict. A system of 800 public buses continued to provide transportation services to the city. | |||

| It is mentioned as ''Kophes'' or ''Kophene'' in some classical Greek writings. The Chinese Buddhist monk ] refers to the city as ''Kaofu''<ref>{{Cite book |title=Chandragupta Maurya and his times |last1=Mookerji |first1=Radhakumud |edition=4 |year=1966 |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass Publ |isbn=978-81-208-0405-0 |page=173 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=i-y6ZUheQH8C&pg=PA173 |access-date=18 September 2010 |archive-date=29 December 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111229185942/http://books.google.com/books?id=i-y6ZUheQH8C&pg=PA173 |url-status=live}}</ref> in the 7th century AD, which is the ] of one of the five tribes of the ] who had migrated from across the ] into the Kabul valley around the beginning of the ].<ref name="Elliot-2">{{cite web |url=http://persian.packhum.org/persian/pf?file=80201012&ct=99 |title=A.—The Hindu Kings of Kábul (p.2) |work=Sir H. M. Elliot |publisher=] |location=London |date=1867–1877 |access-date=18 September 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110905192644/http://persian.packhum.org/persian/pf?file=80201012&ct=99 |archive-date=5 September 2011 |url-status=dead}}</ref> It was conquered by Kushan Emperor ] in about 45 AD and remained Kushan territory until at least the 3rd century AD.<ref>Hill, John E. 2004. ''The Peoples of the West from the Weilue'' 魏略 ''by Yu Huan'' 魚豢'': A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 AD.'' Draft annotated English translation... {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171223070446/http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/weilue/weilue.html |date=23 December 2017 }}</ref><ref>Hill (2004), pp. 29, 352–352.</ref> The Kushans were ] peoples related to the Yuezhi and based in ].<ref>A. D. H. Bivar, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120118071505/http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kushan-dynasty-i-history |date=18 January 2012 }}, in ], 2010</ref> | |||

| Around 230 AD, the Kushans were defeated by the ] and replaced by Sassanid vassals known as the ]. During the Sassanian period, the city was referred to as "Kapul" in ].<ref name="Dupree-name" /> Kapol in the ] means Royal (ka) Bridge (pol), which is due to the main bridge on the Kabul River that connected the east and west of the city. In 420 AD, the Indo-Sassanids were driven out of Afghanistan by the ] tribe known as the ], who were then replaced in the 460s by the ]. It became part of the surviving ] ] ], also known as ''Kabul-Shahan''.<ref name="Elliot">{{cite web |url=http://persian.packhum.org/persian/pf?file=80201012&ct=98 |title=A.—The Hindu Kings of Kábul |work=Sir H. M. Elliot |publisher=] |location=London |date=1867–1877 |access-date=18 September 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140408220905/http://persian.packhum.org/persian/pf?file=80201012&ct=98 |archive-date=8 April 2014 |url-status=dead}}</ref> According to ''Táríkhu-l Hind'' by ], Kabul was governed by princes of ] lineage.<ref name="Elliot" /> It was briefly held by the ] between 801 and 815. | |||

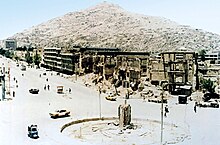

| By 1993 electricity and water in the city was completely out. At this time, ]'s militia (]) held power but the nominal prime minister ]'s ] began shelling the city, which lasted until 1996. Kabul was factionalised, and fighting continued between Jamiat-e Islami, ] and the ]. Tens of thousands of civilians were killed and many more fled as ]. The ] estimated that about 90% of the buildings in Kabul were destroyed during these years.] | |||

| ===The Jewish community=== | |||

| Kabul was captured by the ] in September of 1996, publicly lynching ex-President ] and his brother. During this time, all the fighting between different militias came to an end. Burhannudin Rabbani, Gulbuddin Heckmatyar, Abdul Rashid Dostum, ], and the rest all fled the city. | |||

| {{main|History of the Jews in Afghanistan}} | |||

| ] had a presence in Afghanistan from ancient times until 2021.<ref name=":2">{{Cite news |agency=Associated Press |date=2021-09-08 |title=Last member of Afghanistan's Jewish community leaves country |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/sep/08/afghanistans-last-jew-leaves-country |access-date=2024-07-12 |work=The Guardian |language=en-GB |issn=0261-3077}}</ref> There are records of religious correspondence establishing the presence of Jews in Kabul since the 8th century, though it is believed that they were present centuries or even millennia earlier.<ref name=":3">{{Cite web |title=Jews of Afghanistan: A History of Tolerance and Diversity |url=https://aissonline.org/en/opinions/jews-of-af.../1164 |access-date=2024-07-12 |website=aissonline.org |language=en}}</ref><ref name=":4">{{Cite web |last=Jalalzai |first=Freshta |date=2024-03-08 |title=The Little-Known Story of Afghanistan's Last Jew |url=https://newlinesmag.com/essays/the-little-known-story-of-afghanistans-last-jew/ |access-date=2024-07-12 |website=New Lines Magazine |language=en}}</ref> The 12th century Arab geographer ] wrote down his observations of a Jewish quarter in Kabul.<ref name="Ben">Ben Zion Yehoshua-Raz, “Kabul”, in: ''Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World'', Executive Editor Norman A. Stillman. First published online: 2010</ref> In the early 19th century, Kabul and other major Afghan cities became sites of refuge for Jews fleeing persecution in neighboring Iran.<ref name=":5">{{Cite web |last=Feigenbaum |first=Aaron |title=The Jewish History of Afghanistan |url=https://aish.com/the-jewish-history-of-afghanistan/ |access-date=12 July 2024 |website=Aish}}</ref> | |||

| Jews were generally tolerated for most of their time in Afghanistan, up until the passage of anti-Jewish laws in the 1870s. Jews were given a reprieve under the rule of King ] until his assassination in 1933. The influence of Nazi propaganda led to increased violence against Jews and the ]ization of their communities in Kabul and ]. Most of Afghanistan's Jews fled the country or congregated in these urban hubs.<ref name=":5" /> | |||

| Approximately five years later, in October 2001, the ] invaded Afghanistan. The Taliban abandoned Kabul in the following months due to extensive American bombing, while the ] (former mujahideen or millias) came to retake control of the city. On ], ], Kabul became the capital of the ], which transformed to the present ] that is led by US-backed President ]. | |||

| After the ], the Jewish community requested permission from King ] to migrate there. Afghanistan was the only country that allowed its Jewish residents to migrate to Israel without relinquishing their citizenship.<ref name=":3" /> Most of those remaining, approximately 2,000 in number, left after the ] in 1979.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":4" /> | |||

| Since the beginning of 2003, the city is slowly developing with the help of foreign investment. Security is also improving by the year, despite the occasional attacks on government forces. | |||

| As of 1992, there were believed to be two Jews remaining in Afghanistan, both living in a synagogue in Kabul.<ref name=":4" /> The congregation's ] was confiscated during the ]. ] was believed and widely reported to be Afghanistan's last Jew, until ] fled months after him, with her grandchildren. Moradi, who harbored a rabbi in her home throughout the first Islamic Emirate, lived in ], Kabul for decades. While she was married to a Muslim man as a child, she still covertly attended synagogue and tried to teach her children what Hebrew prayers she could remember from her childhood. As of her departure in November 2021, there are believed to be no Jews in Afghanistan.<ref name=":2" /> | |||

| ==Climate== | |||

| {{-}} | |||

| <!--Infobox begins-->{{Infobox Weather | |||

| |metric_first=yes <!--Entering Yes will display metric first. Leave blank for imperial--> | |||

| |single_line=yes <!--Entering Yes will display metric and imperial units on same line.--> | |||

| |location = {{PAGENAME}} | |||

| |Jan_Hi_°F =36 |Jan_REC_Hi_°F = <!--REC temps are optional; use sparely--> | |||

| |Feb_Hi_°F =40 |Feb_REC_Hi_°F = | |||

| |Mar_Hi_°F =52 |Mar_REC_Hi_°F = | |||

| |Apr_Hi_°F =65 |Apr_REC_Hi_°F = | |||

| |May_Hi_°F =74 |May_REC_Hi_°F = | |||

| |Jun_Hi_°F =84 |Jun_REC_Hi_°F = | |||

| |Jul_Hi_°F =88 |Jul_REC_Hi_°F = | |||

| |Aug_Hi_°F =87 |Aug_REC_Hi_°F = | |||

| |Sep_Hi_°F =80 |Sep_REC_Hi_°F = | |||

| |Oct_Hi_°F =69 |Oct_REC_Hi_°F = | |||

| |Nov_Hi_°F =57 |Nov_REC_Hi_°F = | |||

| |Dec_Hi_°F =44 |Dec_REC_Hi_°F = | |||

| |Year_Hi_°F =64 |Year_REC_Hi_°F = | |||

| ===Islamisation and Mongol invasion=== | |||

| |Jan_Lo_°F =23 |Jan_REC_Lo_°F = | |||

| {{Further|Islamic conquest of Afghanistan}} | |||

| |Feb_Lo_°F =25 |Feb_REC_Lo_°F = | |||

| ] | |||

| |Mar_Lo_°F =37 |Mar_REC_Lo_°F = | |||

| The ] reached modern-day Afghanistan in 642 AD, at a time when Kabul was independent.<ref>{{Cite book |title=Ariana antiqua: a descriptive account of the antiquities and coins of |last1=Wilson |first1=Horace Hayman |year=1998 |publisher=Asian Educational Services |isbn=978-81-206-1189-4 |page=133 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=s_K_gcxHz5YC&pg=PA133 |access-date=18 September 2010 |archive-date=3 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210503084943/https://books.google.com/books?id=s_K_gcxHz5YC&pg=PA133 |url-status=live}}</ref> Until then, Kabul was considered politically and culturally part of the Indian world.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bosworth |first=Clifford Edmund |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Z8YmAQAAMAAJ&q=The+Ghaznavids,+their+empire+in+Afghanistan+and+Eastern+Iran+994%E2%80%931040, |title=The Ghaznavids: Their Empire in Afghanistan and Eastern Iran, 994 : 1040 |date=1973 |publisher=Munshiram Manoharlal |isbn=978-1-01-499132-4 |pages=43 |language=en |access-date=5 April 2023 |archive-date=13 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230513042227/https://books.google.com/books?id=Z8YmAQAAMAAJ&q=The+Ghaznavids,+their+empire+in+Afghanistan+and+Eastern+Iran+994%E2%80%931040, |url-status=live }}</ref> A number of failed expeditions were made to ] the region. In one of them, ] arrived in Kabul from ] in the late 600s and converted 12,000 inhabitants to ] before abandoning the city. ]s were a minority until ] of Zaranj conquered Kabul in 870 from the ] and established the first ] in the region. It was reported that the rulers of Kabul were ]s with non-Muslims living close by. Iranian traveller and geographer ] described it in 921: | |||

| |Apr_Lo_°F =48 |Apr_REC_Lo_°F = | |||

| |May_Lo_°F =54 |May_REC_Lo_°F = | |||

| |Jun_Lo_°F =62 |Jun_REC_Lo_°F = | |||

| |Jul_Lo_°F =67 |Jul_REC_Lo_°F = | |||

| |Aug_Lo_°F =65 |Aug_REC_Lo_°F = | |||

| |Sep_Lo_°F =56 |Sep_REC_Lo_°F = | |||

| |Oct_Lo_°F =45 |Oct_REC_Lo_°F = | |||

| |Nov_Lo_°F =35 |Nov_REC_Lo_°F = | |||

| |Dec_Lo_°F =28 |Dec_REC_Lo_°F = | |||

| |Year_Lo_°F =45 |Year_REC_Lo_°F = | |||

| {{blockquote|Kábul has a castle celebrated for its strength, accessible only by one road. In it there are ], and it has a town, in which are ] from ].<ref name="Elliot-3">{{cite web |url=http://persian.packhum.org/persian/pf?file=80201012&ct=100 |title=A.—The Hindu Kings of Kábul (p.3) |work=Sir H. M. Elliot |publisher=] |location=London |date=1867–1877 |access-date=2010-09-18 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130726133107/http://persian.packhum.org/persian/pf?file=80201012&ct=100 |archive-date=2013-07-26 |url-status=dead}}</ref>}} | |||

| |Jan_Precip_inch =1.3 | |||

| |Feb_Precip_inch =2.1 | |||

| |Mar_Precip_inch =2.8 | |||

| |Apr_Precip_inch =2.6 | |||

| |May_Precip_inch =0.8 | |||

| |Jun_Precip_inch = | |||

| |Jul_Precip_inch =0.2 | |||

| |Aug_Precip_inch =0.1 | |||

| |Sep_Precip_inch =0.1 | |||

| |Oct_Precip_inch =0.2 | |||

| |Nov_Precip_inch =0.4 | |||

| |Dec_Precip_inch =0.8 | |||

| |Year_Precip_inch =10.7 | |||

| Over the following centuries, the city was successively controlled by the ], ], ], ], ], and ]. In the 13th century, the invading ] caused major destruction in the region. Report of a ] in the close by ] is recorded around this period, where the entire population of the valley was annihilated by the Mongol troops as revenge for the death of Genghis Khan's grandson. As a result, many natives of Afghanistan fled south toward the Indian subcontinent where some established ]. The ] and ] were vassals of ] until the dissolution of the latter in 1335. | |||

| |source =weatherbase.com<ref name=weather >{{cite web | |||

| | url =http://www.weatherbase.com/weather/weather.php3?s=84904&refer=&units=us | title =Historical Weather for Kabul | accessmonthday =26 July | accessyear =2007 | |||

| | publisher = | language = }}</ref> | |||

| |accessdate =2007-07-26 | |||

| }}<!--Infobox ends--> | |||

| Following the era of the Khalji dynasty in 1333, the famous ] scholar ] was visiting Kabul and wrote: | |||

| ==Administration== | |||

| {{blockquote|We travelled on to Kabul, formerly a vast town, the site of which is now occupied by a village inhabited by a tribe of Persians called Afghans. They hold mountains and defiles and possess considerable strength, and are mostly highwaymen. Their principal mountain is called ].<ref>{{Cite book |title=Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325–1354 |last1=Ibn Battuta |edition=reprint, illustrated |year=2004 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=0-415-34473-5 |page=180 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zKqn_CWTxYEC&pg=PA180 |access-date=2010-09-10 |archive-date=2017-04-16 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170416132656/https://books.google.com/books?id=zKqn_CWTxYEC&pg=PA180 |url-status=live}}</ref>}} | |||

| Kabul City is one of the 15 districts of ], and is divided into 18 '''sectors'''. Each sector covers several neighborhoods of the city. The number of Kabul's sectors were increased from 11 to 18 in 2005. | |||

| ===Timurid and Mughal era=== | |||

| Unlike other cities of the world, Kabul City has two independent councils or administrations at once: ] and ]. The ] who is also the ] of Kabul Province is appointed by the ], and is responsible for the administrative and formal issues of the entire province. The ] of Kabul City is selected by the ], who engages in the city's planning and environmental work. | |||

| {{Further|Timurid Empire|Mughal Empire}} | |||

| ] with his father ], emperors of the ]]] | |||

| ] of Kabul]]In the 14th century, Kabul became a major trading centre under the kingdom of ] (''Tamerlane''). In 1504, the city fell to ] from the north and made into his headquarters, which became one of the principal cities of his later ]. In 1525, Babur described ] in ] by writing that: | |||

| {{blockquote|There are many differing tribes in the ]; in its dales and plains are Turks and clansmen and ]; and in its town and in many villages, ]; out in the districts and also in villages are the ], ], ], ] and ] tribes. In the western mountains are the ] and ] tribes, some of whom speak the ] tongue. In the north-eastern mountains are the places of the ], such as ]. To the south are the places of the ].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.gutenberg.org/files/44608/44608-h/44608-h.htm |title=Description of Kābul |access-date=June 21, 2021 |author=] |work=] |publisher=Packard Humanities Institute |year=1525 |archive-date=June 30, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200630231822/http://www.gutenberg.org/files/44608/44608-h/44608-h.htm |url-status=live}}</ref>}} | |||

| The police and security forces belong to the prefecture and Ministry of Interior. The Chief of Police is selected by the Minister of Interior and is responsible for law enforcement and security of the city. | |||

| ], a poet from ] who visited at the time wrote: ''"Dine and drink in Kabul: it is mountain, desert, city, river and all else."'' It was from here that Babur began his 1526 conquest of Hindustan, which was ruled by the ] ] and began east of the ] in what is present-day ]. ] loved Kabul due to the fact that he lived in it for 20 years and the people were loyal to him, including the weather that he was used to. His wish to be buried in Kabul was finally granted. The inscription on his ] contains the famous Persian ], which states: | |||

| ] | |||

| اگرفردوس روی زمین است همین است و همین است و همین است | |||

| * '''Areas of Kabul City''' | |||

| ** Shahr-e Naw (New City) | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** Macro Ryans (1, 2, 3 and 4) | |||

| ** Khair Khana (1, 2 and 3) | |||

| ** Dashti Barchi | |||

| ** Kartey Sakhi | |||

| ** Qalai Wazir | |||

| ** Khushhall Khan | |||

| ** Afshar | |||

| ** Klola Pushta and Taimani | |||

| ** Kartey Parwan | |||

| ** Kartey Naw (''New Quarter'') | |||

| ** Kartey (3 & 4) | |||

| ** Darul-Aman | |||

| ** Chehlstoon | |||

| ** Chendawol | |||

| ** Shahr-e Kohna (Old City of Kabul) | |||

| ** Deh Buri | |||

| ** Bibi Mahroo | |||

| Transliteration: | |||

| == Demographics == | |||

| ] | |||

| Kabul has a population between 2.5 to approximately 3 million people. The population of the city reflects the general multi-ethnic, multi-cultural, and multi-confessional characteristics of Afghanistan. According to the 2005 ] estimate, the population of Kabul City reached 2,994,000,<ref>UN World Urbanization Prospects: The 2005 Revision Population Database...</ref> while according to the 2006 estimates from the ], the city's population is only 2,536,300.<ref>Central Statistics Office, Annual Report, Kabul-Afghanistan, </ref> | |||

| Agar fardus rui zamayn ast', hameen ast', o hameen ast', o hameen ast'. | |||

| ] form the majority of the city's population, with the predominately ] ] being the largest group,<ref name=Encarta>{{cite encyclopedia |last= |first= |author= |authorlink= |coauthors= |editor= |encyclopedia= Microsoft® Encarta® Online Encyclopedia |title= Kābul (city)|url= http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761557246/K%C4%81bul_(city).html|accessdate=2007-12-02 |accessyear= |accessmonth= |edition= 2007|date= |year= |month= |publisher= |volume= |location= |id= |doi= |pages= |quote= Tajiks are the important predominant population group of Kābul, and Pashtuns are an minority.}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2006/05/30/18259841.php |title=Kabul under Curfew after Anti-US, anti-Karzai Riots |accessdate=2007-11-27 |last=Cole |first=Juan |coauthors= |date=2006-30-05 |work= |publisher=San Francisco Bay Area Indymedia}}</ref> followed by ] ]s. There is also a large number of ] and some of them are already persianized. | |||

| (If there is a paradise on earth, it is this, and it is this, and it is this!)<ref>{{Cite book |title=War Against the Taliban: Why It All Went Wrong in Afghanistan |last1=Gall |first1=Sandy |year=2012 |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |isbn=978-1-4088-0905-1 |page= |url=https://archive.org/details/waragainsttaliba0000gall |url-access=registration |access-date=30 September 2013}}</ref> | |||

| ]-speakers, also Sunnites, form the most important minority, followed by the ] ]. There are also sizable numbers of ], ], ], as well as ] and ] who speak their native language as their mother tongue and Persian as the native language of Kabul. | |||

| Kabul remained in Mughal control for the next 200 years.<ref name=":0">{{cite web |last=Schinasi |first=May |title=Kabul iii. History From the 16th Century to the Accession of Moḥammad Ẓāher Shah |url=https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kabul-iii-history |access-date=29 June 2021 |website=Encyclopaedia Iranica |language=en-US |archive-date=29 June 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210629170713/https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kabul-iii-history |url-status=live}}</ref> Though Mughal power became centred within the ], Kabul retained importance as a frontier city for the empire; ], Emperor ] chronicler, described it as one of the two gates to Hindustan (the other being ]).<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Samrin |first=Farah |title=The City of Kabul Under the Mughals |date=2005 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/44145943 |journal=Proceedings of the Indian History Congress |volume=66 |page=1307 |jstor=44145943 |issn=2249-1937 |access-date=29 June 2021 |archive-date=29 June 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210629170711/https://www.jstor.org/stable/44145943 |url-status=live}}</ref> As part of administrative reforms under Akbar, the city was made capital of the eponymous Mughal province, ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Roy |first=Kaushik |date=January 2015 |title=Mughal Empire and Warfare in Afghanistan: 1500–1810 |url=https://academic.oup.com/book/4199/chapter-abstract/146011616?redirectedFrom=fulltext |access-date=2023-06-20 |website=academic.oup.com |archive-date=20 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230620230909/https://academic.oup.com/book/4199/chapter-abstract/146011616?redirectedFrom=fulltext |url-status=live }}</ref> Under Mughal governance, Kabul became a prosperous urban centre, endowed with bazaars such as the non-extant ].<ref name=":0" /> For the first time in its history, Kabul served as a mint centre, producing gold and silver Mughal coins up to the reign of ].<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |last=Bosworth |first=Clifford Edmund |title=Historic cities of the Islamic world |date=2008 |publisher=Brill |isbn=978-90-04-15388-2 |page=257 |oclc=231801473}}</ref> It acted as a military base for ] ] in ] and ]. Kabul was also a recreational retreat for the Mughals, who hunted here and constructed several gardens. Most of the Mughals' architectural contributions to the city (such as gardens, fortifications, and mosques) have not survived.<ref name=":0" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Foltz |first=Richard |date=1996 |title=The Mughal Occupation of Balkh 1646–1647 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/26195477 |journal=Journal of Islamic Studies |volume=7 |issue=1 |page=52 |doi=10.1093/jis/7.1.49 |jstor=26195477 |issn=0955-2340 |access-date=29 June 2021 |archive-date=29 June 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210629170710/https://www.jstor.org/stable/26195477 |url-status=live}}</ref> During this time, the population was about 60,000.<ref name="undermughal" /> | |||

| == Transport == | |||

| ] serves the population of the city as a method of traveling to other cities or countries. The airport is a hub to ], which is the national airlines carrier of Afghanistan. However, airlines from other nations also use the airport to arrive and depart. A new $35 million dollar terminal for international flight passengers, near the old terminal, is under construction and will be completed by 2008.<ref>Pajhwok Afghan News - ''Work on terminal at Kabul Airport starts''...</ref> | |||

| Under later ], Kabul became neglected.<ref name=":0" /> The empire lost the city when it was captured in 1738 by ], who was en route to ].<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| ] district of the city.]] | |||

| ===Durrani and Barakzai dynasties=== | |||

| Kabul has its own public buses (Millie Bus) that take ] on daily routes to many destinations throughout the city. The service currently has approximately 800 buses but is gradually expanding and upgrading with more buses being added. Plans are underway to re-introduce the modern ]es that the city once had. Besides the buses, there are yellow ]s that can be spotted just about anywhere in and around the city. | |||

| {{Further|Durrani dynasty|Barakzai dynasty}} | |||

| ], the last ], sitting at his court inside the ]]] | |||

| ] (also known as "Hendaki"), one of numerous palaces built by the Emir in the 19th century]] | |||

| Nine years after ] and his forces invaded and occupied the city as part of the more easternmost parts of his Empire, he was assassinated by his own officers, causing its rapid disintegration. ], commander of 4,000 ] ], asserted ] rule in 1747 and further expanded his new ]. His ascension to power marked the beginning of Afghanistan. By this time, Kabul had lost its status as a metropolitan city, and its population had decreased to 10,000.<ref>{{Citation |last=Ziad |first=Waleed |title=From Yarkand to Sindh via Kabul: The Rise of Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Sufi Networks in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries |date=30 October 2018 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/9789004387287_007 |work=The Persianate World |page=145 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211122095707/https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004387287/BP000012.xml |publisher=BRILL |doi=10.1163/9789004387287_007 |isbn=978-90-04-38728-7 |s2cid=197951160 |access-date=11 November 2021 |archive-date=22 November 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> Interest in the city was renewed when Ahmad Shah's son ], after inheriting power, transferred the capital of the Durrani Empire from ] to Kabul in 1776.<ref name="Stanford">Hanifi, Shah Mahmoud. p. 185. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210815092453/https://books.google.com/books?id=kh1hpPLSpcEC |date=15 August 2021 }}. ], 2011.</ref><ref name=":0" /> Kabul experienced considerable urban development during the reigns of Timur Shah and his successor ]; several religious and public buildings were constructed, and diverse groups of ], jurists, and literary families were encouraged to settle the city through land grants and stipends.<ref>{{Citation |last=Ziad |first=Waleed |title=From Yarkand to Sindh via Kabul: The Rise of Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Sufi Networks in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries |date=30 October 2018 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/9789004387287_007 |work=The Persianate World |pages=148–149 |publisher=BRILL |doi=10.1163/9789004387287_007 |isbn=978-90-04-38728-7 |s2cid=197951160 |access-date=18 December 2021 |archive-date=22 November 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211122095707/https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004387287/BP000012.xml |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name=":0" /> Kabul's first visitor from Europe was Englishman ], who described 18th-century Kabul as "the best and cleanest city in Asia".<ref name="BBC-Kabul">{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/1651814.stm |title=Kabul: City of lost glories |date=12 November 2001 |access-date=18 September 2010 |work=BBC News |archive-date=2 October 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131002212006/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/1651814.stm |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| In 1826, the kingdom was claimed by ], but in 1839 ] was re-installed with the help of the ] during the ]. In 1841 a local uprising resulted in the killing of the British resident and loss of mission in Kabul and the ] to ], in which 4,500 regular British troops and 14,000 civilians were killed by Afghan tribesmen. In 1842 the British returned to Kabul, demolishing the city's main '']'' in revenge during the ] before returning to ] (now Pakistan). ] took to the throne from 1842 to 1845 and was followed by Dost Mohammad Khan.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Story Map Cascade |url=https://www.loc.gov/ghe/cascade/index.html?appid=a0930b1f4e424987ba68c28880f088ea |access-date=2023-06-20 |website=Library of Congress |archive-date=17 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210817041928/https://loc.gov/ghe/cascade/index.html?appid=a0930b1f4e424987ba68c28880f088ea |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Private vehicles are also on the rise in Kabul, with ], ], ], ] and ] dealerships in the city. More people are buying new cars as the roads and highways are being improved. The average car driven in Kabul is a ]. With the exception of motorcycles many vehicles in the city operate on LPG. | |||

| ] | |||

| == Communications == | |||

| The ] broke out in 1879 when Kabul was under ]'s rule, as the Afghan king initially refused to accept British diplomatic missions and later the British residents were again massacred. During the war, Bala Hissar was partially destroyed by a fire and an explosion.<ref name="lib">Caption for Panorama of the Bala Hissar WDL11486 Library of Congress</ref> | |||

| ]/] mobile phone services in the city are provided by ], ], ] and ]. In November 2006, the ] signed a ] 64.5 million dollar agreement with a company (ZTE Corporation) on the establishment of a countrywide fibre optical cable network. This will improve telephone, internet, television and radio broadcast services not just in Kabul but throughout the country.<ref> Pajhwok Afghan News - ''Ministry signs contract with Chinese company''...</ref> Internet was introduced in the city in 2002 and has been expanding rapidly. | |||

| ===20th century=== | |||

| There are a number of post offices throughout the city. Package delivery services like ], ] and others are also available. | |||

| In Kabul, an established ] city, leather and textile industries developed by 1916.<ref name="pdf.usaid.gov">{{cite web |title=Draft Kabul City Master Plan |url=https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00JMMJ.pdf |website=usaid.gov |access-date=21 November 2019 |archive-date=2 April 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190402205705/https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00JMMJ.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> The majority of the population was concentrated on the south side of the river. | |||

| The city was modernised throughout the regime of King ], with the introduction of electricity, telephone, and a postal service.<ref>Tanin, Z. (2006): Afghanistan in the 20th Century. Tehran.</ref> The first modern high school, ], was established in 1903. In 1919, after the ], King ] announced Afghanistan's independence in ] at ] in Kabul. Amanullah was reform-minded and he had a plan to build a new ] on land 6 km from Kabul. This area, named ], consisted of the famous ], where he later resided. Many educational institutions were founded in Kabul during the 1920s. In 1929 King Amanullah left Kabul after a local uprising orchestrated by ], but he was imprisoned and executed after nine months in power by King ]. Three years later, in 1933, the new king was assassinated during an award ceremony in a school in Kabul. The throne was left to his 19-year-old son, ], who became the last ]. Unlike Amanullah Khan, Nader Khan and Zahir Shah had no plans to create a new capital city, and thus Kabul remained the country's ]. | |||

| The city has many local radio stations which also have programs in the ]. Besides foreign channels, the local television channels of Afghanistan include: | |||

| ] | |||

| *] | |||

| During the ], France and Germany helped to develop the country and maintained high schools and lycees in the capital, providing education for the children of the city's elite families.<ref>Anthony Hyman, "Nationalism in Afghanistan" in ''International Journal of Middle East Studies'', 34:2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002) 305.</ref> ] opened in 1932, and by the 1960s the majority of teachers were western educated Afghans<ref name="Hyman, 305">Hyman, 305.</ref> and the majority of instructors at the university had degrees from Western universities.<ref name="Hyman, 305" /> | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| Kabul's only railway service, the ], operated for six years from 1923 to 1929.<ref name="andrewgrantham.co.uk">{{cite web |title=Kabul New City light rail plan – Railways of Afghanistan |url=http://www.andrewgrantham.co.uk/afghanistan/kabul-new-city-light-rail-plan/ |website=www.andrewgrantham.co.uk |date=18 August 2015 |access-date=26 January 2018 |archive-date=26 January 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180126125644/http://www.andrewgrantham.co.uk/afghanistan/kabul-new-city-light-rail-plan/ |url-status=live}}</ref> When Zahir Shah took power in 1933, Kabul had the only {{convert|6|mi|sp=us|0|abbr=off|order=flip}} of rail and the country had few internal telegraphs, phone lines or roads. Zahir turned to the Japanese, Germans and Italians for help in developing a modern transportation and communications network.<ref>Nick Cullather, "Damming Afghanistan: Modernisation in a Buffer State" in ''The Journal of American History'' 89:2 (Indiana: Organization of American Historians, 2002) 518.</ref> A radio tower built in Kabul by the Germans in 1937 provided communication with outlying villages.<ref>Cullather, 518.</ref> A national bank and state cartels were organised to allow for economic modernisation.<ref name="Cullather, 519">Cullather, 519.</ref> Textile mills, power plants, carpet and furniture factories were built in Kabul, providing much-needed manufacturing and infrastructure.<ref name="Cullather, 519" /> | |||

| == Education == | |||

| ].]] | |||

| All public schools in Kabul began to re-open in 2002, and ever since then they are improving every year. Many boys and girls are now attending classes. Some of the public schools are ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| There are also several new universities and private colleges opened in the last few years. | |||

| During the 1940s and 1950s, ] accelerated and the ] was increased in size to 68 km<sup>2</sup> by 1962, an almost fourteen-fold increase since 1925.<ref name="pdf.usaid.gov" /> The ] opened in 1945 as the first Western-style luxury hotel. In the 1950s, under the premiership of ], foreign investment and development increased. In 1955, the Soviet Union forwarded $100 million in credit to Afghanistan which financed public transportation, airports, a cement factory,a mechanised bakery, a five-lane highway from Kabul to the Soviet border and dams, including the ] to the north of Kabul.<ref>Cullather, 530.</ref> During the 1960s, Soviet-style ] housing estates were built, containing sixty blocks. The government also built many ministry buildings in the ] style.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Caryl |first1=Christian |title=When Afghanistan Was Just a Stop on the 'Hippie Trail' |url=https://www.huffpost.com/entry/strange-rebels-excerpt_b_3427854 |website=HuffPost |language=en |date=12 June 2013 |access-date=21 November 2019 |archive-date=26 June 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190626204243/https://www.huffpost.com/entry/strange-rebels-excerpt_b_3427854 |url-status=live}}</ref> In the 1960s the first ] store in ] was built in the city. ] was inaugurated in 1967, which was maintained with the help of visiting German ]. During this time, Kabul experimented with liberalisation, notably the loosening of restrictions on speech and assembly, which led to student politics in the capital and demonstrations by Socialist, Maoist, liberal or Islamist factions.<ref name="Cullather, 534">Cullather, 534.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ====Universities in Kabul==== | |||

| Foreigners flocked to Kabul as the nation's tourism industry expanded. To accompany the city's new-found tourism, western-style accommodations were opened in the 1960s, notably the Spinzar Hotel.<ref name="hotel tourists">{{cite web |url=https://ackuimages.photoshelter.com/image/I0000n5RXicm0vfM |title=Hotels and Tourists. | ACKU Images System |access-date=31 August 2021 |archive-date=31 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210831210756/https://ackuimages.photoshelter.com/image/I0000n5RXicm0vfM |url-status=live}}</ref> Western, American and Japanese tourists visited the city's attractions<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.rferl.org/a/Afghans_Prepare_For_Tourism_Development/1843909.html |title=Afghans Prepare for Tourism Development |newspaper=Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty |date=5 October 2009 |access-date=31 August 2021 |archive-date=31 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210831210754/https://www.rferl.org/a/Afghans_Prepare_For_Tourism_Development/1843909.html |url-status=live |last1=Blua |first1=Antoine }}</ref> including ]<ref name="Amstutz 1994">{{cite book |last=Amstutz |first=J. Bruce |publisher=Diane Publishing |isbn=978-0-7881-1111-2 |url=https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_RUSNyMH1aFQC |title=Afghanistan: The First Five Years of Soviet Occupation |year=1994 |oclc=948347893}}</ref> and the ] that contained some of Asia's finest cultural artifacts.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/21/travel/21kabul.html |title=The Mysteries of Kabul |newspaper=The New York Times |date=21 January 2007 |last1=Hammer |first1=Joshua |access-date=1 September 2021 |archive-date=1 September 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210901154024/https://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/21/travel/21kabul.html |url-status=live}}</ref> ] called it an upcoming "tourist trap" in 1973.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/middle-east/afghanistan/articles/when-afghanistan-was-just-the-laid-back-highlight-on-the-hippie-/ |title=When Afghanistan was just a laid-back highlight on the hippie trail |newspaper=The Telegraph |date=20 April 2018 |last1=Smith |first1=Oliver |access-date=31 August 2021 |archive-date=17 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210817013308/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/middle-east/afghanistan/articles/when-afghanistan-was-just-the-laid-back-highlight-on-the-hippie-/ |url-status=live}}</ref> Pakistanis visited to watch Indian movies that were banned in their own country.<ref name="hotel tourists" /> Kabul was nicknamed the ''Paris of Central Asia''.<ref name="Golden" /><ref name="Glory" /> According to ], an American diplomat in Kabul: | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| {{blockquote| Kabul was a pleasant city Though poor economically, it was spared the eyesore slums so visible in other Asian cities. The Afghans themselves were an imposing people, the men tall and self-assured and the women attractive.<ref name="Amstutz 1994" />}} | |||

| == Tourism and sightseeing == | |||

| The old part of Kabul is filled with ]s nestled along its narrow, crooked streets. Cultural sites include the ], notably displaying an impressive statue of ] excavated at Khair Khana, the ruined ], the ] of Emperor ] and Chehlstoon Park, the Minar-i-Istiqlal (Column of Independence) built in 1919 after the ], the mausoleum of ], and the imposing ] (founded 1893). ] is a fort destroyed by the British in 1879, in retaliation for the death of their envoy, now restored as a military college. The Minaret of Chakari, destroyed in 1998, had ] ] and both ] and ] qualities. | |||

| Until the late 1970s, Kabul was a stop on the ] from ] to the west towards ].<ref>{{cite news |title=The Lonely Planet Journey: The Hippie Trail |url=https://www.independent.co.uk/travel/europe/the-lonely-planet-journey-the-hippie-trail-6257275.html |access-date=14 June 2017 |agency=The Independent |date=5 November 2011 |archive-date=15 June 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170615005133/http://www.independent.co.uk/travel/europe/the-lonely-planet-journey-the-hippie-trail-6257275.html |url-status=live}}</ref> The city was known for its street sales of ] and became a major attraction for western ].<ref name="overthrown">{{cite news |title=Afghan King Overthrown; A Republic Is Proclaimed |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1973/07/18/archives/afghan-king-overthrown-a-republic-is-proclaimed-afghanistan-king-is.html |website=The New York Times |date=18 July 1973 |access-date=1 April 2019 |archive-date=29 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191129042317/https://www.nytimes.com/1973/07/18/archives/afghan-king-overthrown-a-republic-is-proclaimed-afghanistan-king-is.html |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ====Occupations, wars and Taliban rule (1996–2001)==== | |||

| Other places of interest include ], which is Kabul's first shopping mall, the shops around Flower Street and Chicken Street, Wazir Akbar Khan district, ], ], ], Shah Do Shamshera and other famous ]s, the Afghan National Gallery, Afghan National Archive, Afghan Royal Family Mausoleum, the ], Bibi Mahroo Hill, Kabul Cemetery, and ]. | |||

| {{Further|Soviet–Afghan War|Afghan Civil War (1989–92)}} | |||

| ] to the old city in the south bank]] | |||

| On 28 April 1978, President Daoud and most of his family were assassinated in Kabul's ] in what is called the ]. Pro-Soviet PDPA under ] seized power and slowly began to institute reforms.<ref name="Haynes, 372">Haynes, 372.</ref> Private businesses were nationalised in the Soviet manner.<ref name="Haynes, 373">Haynes, 373.</ref> Education was modified into the Soviet model, with lessons focusing on teaching ], ] and learning of other countries belonging to the Soviet bloc.<ref name="Haynes, 373" /> | |||

| Amid growing internal chaos and heightened cold war tensions, the U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan, ], was kidnapped on his way to work at the U.S. Embassy in Kabul on 14 February 1979 and killed during a rescue attempt at the Serena Hotel. There were conflicting reports of who abducted Dubs and what demands were made for his release. Several senior Soviet officials were in the lobby of the hotel during a standoff with the kidnappers, who were holding Dubs in room 117.<ref>J. Robert Moskin, American Statecraft: The Story of the U.S. Foreign Service (Thomas Dunne Books, 2013), p. 594.</ref><ref>John Prados, Safe for Democracy: The Secret Wars of the CIA (Rowman & Littlefield, 2006), p. 468.</ref> Afghan police, acting on the advice of Soviet advisors and over the objections of U.S. officials, launched a rescue attempt, during which Dubs was shot in the head from a distance of six inches and killed.<ref>Dick Camp, Boots on the Ground: The Fight to Liberate Afghanistan from Al-Qaeda and the Taliban (Zenith, 2012), pp. 8–9.</ref> Many questions about the killing remain unanswered. | |||

| Tappe-i-Maranjan is a nearby hill where Buddhist ]s and Graeco-Bactrian ]s from the 2nd century BC have been found. Outside the city proper is a citadel and the royal palace. ] and ] are interesting valleys north and east of the city. | |||

| On 24 December 1979, the ] invaded Afghanistan and Kabul was heavily occupied by ]. In Pakistan, ] of the ISI ] advocated for the idea of covert operation in Afghanistan by arming Islamic extremists who formed the mujahideen.<ref name="Jang Publishers, 1991" /> General Rahman was heard loudly saying: "''Kabul must burn! Kabul must burn!''",<ref name="Kakar">{{cite book |title=Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982 |last1=Kakar |first1=Hassan M. |year=1997 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-20893-3 |page=291 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QyTmFj5tUGsC&pg=PA291 |access-date=8 January 2013 |archive-date=3 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210503084850/https://books.google.com/books?id=QyTmFj5tUGsC&pg=PA291 |url-status=live}}</ref> and mastered the idea of ] in Afghanistan.<ref name="Jang Publishers, 1991">{{cite book |last=Yousaf |first=Mohammad |title=Silent Soldier: The Man Behind the Afghan Jehad General Akhtar Abdur Rahman |year=1991 |publisher=Jang Publishers, 1991 |location=Karachi, Sindh |page=106 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cAoNAAAAIAAJ&q=Silent+soldier: |access-date=15 December 2015 |archive-date=3 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210503084914/https://books.google.com/books?id=cAoNAAAAIAAJ&q=Silent+soldier%3A |url-status=live}}</ref> Pakistani President ] authorised this operation under General Rahman, which was later merged with ], a programme funded by the ] and carried out by the ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] in 1987, the Soviet Army headquarters during the Soviet–Afghan War]] | |||

| *'''Airports''' | |||