| Revision as of 16:48, 21 August 2008 editTedickey (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers54,471 edits rv - same reason as before (editor is injecting opinion rather than reliable sources)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 13:48, 5 January 2025 edit undoDoug Weller (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Oversighters, Administrators264,061 edits Restored revision 1266086767 by BD2412 (talk): Sauer not an RS, article isn't discussing where Leifsbudir was supposed to be, Wallace believesTags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| {{euromericas}} | |||

| {{About|the Viking presence in the western Arctic|the Swedish|Swedish colonization of the Americas|Danish-Norwegian|Danish colonization of the Americas}} | |||

| As early as the 10th century ] sailors (often referred to as ]s) explored and settled areas of the ], including the northeastern fringes of ]. | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2024}} | |||

| {{Norse colonization of North America}}{{euromericas}} | |||

| The '''Norse exploration of North America''' began in the late 10th century, when ] explored areas of the North ] colonizing ] and creating a short term settlement near the northern tip of ]. This is known now as ] where the remains of buildings were found in 1960 dating to approximately 1,000 years ago.<ref name="Nydal1989">{{cite journal | last1 = Nydal | first1 = Reidar | title = A Critical Review of Radiocarbon Dating of a Norse Settlement at L'Anse Aux Meadows, Newfoundland Canada | journal = Radiocarbon | date = 1989 | volume = 31 | issue = 3 | pages = 976–985 | issn = 0033-8222 |doi = 10.1017/S0033822200012613 | pmid = | s2cid = 129636032 | url = | doi-access = free | bibcode = 1989Radcb..31..976N }}</ref><ref name="CordellLightfoot2008">{{cite encyclopedia |first1=Linda S. |last1=Cordell |first2=Kent |last2=Lightfoot |first3=Francis |last3=McManamon |first4=George |last4=Milner |title=L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site |encyclopedia=Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=arfWRW5OFVgC&pg=PA82 |date=2009 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-0-313-02189-3 |page=82 |access-date=21 October 2021 |archive-date=25 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230425150120/https://books.google.com/books?id=arfWRW5OFVgC&pg=PA82 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Kuitems|first1=Margot|last2=Wallace|first2=Birgitta L.|last3=Lindsay|first3=Charles|last4=Scifo|first4=Andrea|last5=Doeve|first5=Petra|last6=Jenkins|first6=Kevin|last7=Lindauer|first7=Susanne|last8=Erdil|first8=Pınar|last9=Ledger|first9=Paul M.|last10=Forbes|first10=Véronique|last11=Vermeeren|first11=Caroline|date=20 October 2021|title=Evidence for European presence in the Americas in ad 1021|journal=Nature|volume=601|issue=7893|language=en|pages=388–391|doi=10.1038/s41586-021-03972-8|pmid=34671168|pmc=8770119|bibcode=2022Natur.601..388K |issn=1476-4687}}</ref> This discovery helped reignite archaeological exploration for the Norse in the North Atlantic.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/vikingsnorthatla00fitz |title=Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga |date=2000 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-56098-970-7 |editor-last=Fitzhugh |editor-first=William W. |location=Washington |editor-last2=Ward |editor-first2=Elisabeth I. |url-access=registration}}</ref> This single settlement, located on the island of Newfoundland and not on the North American mainland, was abruptly abandoned. | |||

| The Norse settlements on Greenland lasted for almost 500 years. L'Anse aux Meadows, the only confirmed Norse site in present-day Canada,<ref name="Parks Canada 2018">{{cite web|title=L'Anse aux Meadows|work=L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada|publisher=Parks Canada|year=2018|url=https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/lhn-nhs/nl/meadows|access-date=21 December 2018|quote=Here Norse expeditions sailed from Greenland, building a small encampment of timber-and-sod buildings ...|archive-date=9 December 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191209172532/https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/lhn-nhs/nl/meadows|url-status=live}}</ref> was small and did not last as long. Other such Norse voyages are likely to have occurred for some time, but there is no evidence of any Norse settlement on mainland North America lasting beyond the 11th century. | |||

| Unlike ], which the Norse occupied for almost 500 years, the continental North American settlements were small and did not develop into permanent colonies. This was in part due to hostile relations with the ]s, referred to as '']'' by the Norse. Settlements in continental North America aimed to exploit natural resources such as furs and in particular lumber, which was in short supply in Greenland due to deforestation.<ref>]: '']''</ref> Despite some later voyages, there is little supporting evidence of enduring Norse settlements in North America.<ref>Irwin, Constance; Strange Footprints on the Land; Harper&Row, New York, 1980; ISBN 0-06-022772-9</ref> | |||

| The Norse exploration of North America has been subject to numerous controversies concerning the ] and settlement of ].<ref name="Feder2020">{{Cite book |last=Feder |first=Kenneth L. |title=Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology |title-link=Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries |publisher=] |year=2020 |isbn=978-0-19-009642-7 |edition=10th |location=New York |pages=127–137 |oclc=1108812780}}</ref> Pseudoscientific and pseudohistorical theories have emerged since the public acknowledgment of these Norse expeditions and settlements.<ref name="Feder2020" /> | |||

| ==Greenland== | |||

| {{POV-section|date=August 2008}} | |||

| {{Cleanup-section|date=August 2008}} | |||

| {{main|History of Greenland}} | |||

| ==Norse Greenland== | |||

| According to the ], Norsemen from ] first discovered Greenland in the 980s. ] sailed 450 miles to lead a settlement expedition there in 982. He was banished from Iceland for three years because he had killed two sons of a farmer named Thorgost, after an argument about some allegedly stolen lumber. The settlement Erik led was springy with ] and wild ] grew almost everywhere. He named the ] "Eiriksfjord" and, as an act of leadership, took the best land for himself and issued tracts of land to his followers.<ref name = ROBW>Wernick, Robert; ''The Seafarers: The Vikings,'' (1979), 176 pages, Time-Life Books, Alexandria, Virginia: ISBN 0809427095.</ref> | |||

| {{Main article|Norse settlements in Greenland }} | |||

| ] on ], covering approximately the modern municipality of ]. Eiriksfjord (Erik's fjord) and his farm ] are shown, as is the location of the bishopric at Gardar.]] | |||

| According to the ], Norsemen from ] first settled Greenland in the 980s. There is no special reason to doubt the authority of the information that the sagas supply regarding the very beginning of the settlement, but they cannot be treated as primary evidence for the history of Norse Greenland because they embody the literary preoccupations of writers and audiences in medieval Iceland that are not always reliable.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Grove |first=Jonathan |date=2009 |title=The Place of Greenland in Medieval Icelandic Saga Narrative |journal=] |volume=201 |pages=30–51 |doi=10.3721/037.002.s206 |issn=1935-1933 |jstor=26686936}}</ref> | |||

| ] (Old Norse: Eiríkr rauði), having been banished from Iceland for ], explored the uninhabited southwestern coast of Greenland during the three years of his banishment.<ref>He remained there making explorations for three years and decided to found a settlement there ({{cite web |url=http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/nda/nda27.htm |title=Norse voyages in the tenth and following centuries |access-date=27 August 2008 |last=Anderson |first=Rasmus B. |editor-first=John Bruno |editor-last=Hare |date=18 February 2004 |orig-year=1906 |work=The Norse Discovery of America |archive-date=2 January 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200102155739/https://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/nda/nda27.htm |url-status=live }}).</ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=Reeves |first1=Arthur Middleton |author-link=Arthur Middleton Reeves |first2=Rasmus B. |last2=Anderson |url=http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/nda/nda18.htm |title=Discovery and colonization of Greenland |access-date=27 August 2008 |year=1906 |work=Saga of Erik the Red |quote=The first winter he was at Eriksey, nearly in the middle of the ]; the spring after repaired he to Eriksfjord, and took up there his abode. He removed in summer to the western settlement, and gave to many places names. He was the second winter at Holm in Hrafnsgnipa, but the third summer went he to Iceland, and came with his ship into Breidafjord. |archive-date=10 January 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200110123718/https://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/nda/nda18.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> He made plans to entice settlers to the area, naming it Greenland on the assumption that "people would be more eager to go there because the land had a good name".<ref>{{ws|] at Wikisource}}</ref> The inner reaches of one long ], named ''Eiriksfjord'' after him, was where he eventually established his estate '']''. He issued tracts of land to his followers.<ref name="ROBW">{{Cite book |last=Wernick |first=Robert |title=The Vikings |date=1979 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-8094-2709-3 |series=The Seafarers |location=Alexandria, Va}}</ref> | |||

| ], ] and ]. Eiriksfjord (Erik's fjord) and his farm ] are shown, as is the location of the bishopric at Gardar.]] | |||

| At its peak, the colony consisted of two settlements, the ] and the ], with a total population of between 3000 and 5000; at least 400 farms have been identified by archaeologists.<ref name=ROBW/> Norse Greenland had a ] (at ]) and exported walrus ], furs, rope, sheep, whale or seal ], live animals such as ]s, and cattle hides. In 1261, the population accepted the overlordship of the ] King although it continued to have its own law. In 1380, the Norwegian Kingdom entered into a personal union with the Kingdom of ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| The colony began to decline in the 1300s. The Western Settlement was abandoned around 1350 and by 1378 there was no longer a bishop at Garðar. After a marriage was recorded in 1408, no written records mention the settlers. It is probable that the Eastern Settlement was defunct by the late 1400s, although no exact date has been established. The most recent ] date found in Norse settlements as of 2002 was 1430 A.D. (+/- 15 years). Several theories have been advanced to explain the decline. The ] of this period would have made it harder to travel between Greenland and ], as well as making it more difficult for the Greenlanders to farm; in addition, Greenlandic ivory may have been supplanted in European markets by cheaper ivory from ]. Despite the loss of contact with the Greenlanders, the Norwegian-Danish ] continued to consider Greenland a possession and the existence of the island was not forgotten by European ]s. It is also possible that the lands west of Greenland were remembered. | |||

| Norse Greenland consisted of two settlements. The Eastern was at the southwestern tip of Greenland, while the ] was about 500 km up the west coast, inland from present-day ]. A smaller settlement near the Eastern Settlement is sometimes considered the ]. The combined population was around 2,000–3,000.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Lynnerup | first1 = Niels | year = 2014 | title = Endperiod Demographics of the Greenland Norse | journal = Journal of the North Atlantic | volume = 7 | issue = sp7| pages = 18–24 | doi = 10.3721/037.002.sp702 | s2cid = 163050538 | jstor= 26671842}}</ref> At least 400 farms have been identified by archaeologists.<ref name="ROBW" /> Norse Greenland had a ] (at ]) and exported ], furs, rope, sheep, whale and seal ], live animals such as ]s, supposed "unicorn horns" (in reality ]), and cattle hides. In 1126, the population requested a bishop (headquartered at Garðar), and in 1261, they accepted the overlordship of the Norwegian king. They continued to have their own law and became almost completely politically independent after 1349, the time of the ]. In 1380, the Kingdom of Norway entered into ] with the Kingdom of ].<ref name="TVA">{{cite book |last1=Wahlgren |first1=Erik |title=The Vikings and America |date=1986 |publisher=Thames and Hudson |location=New York |isbn=0-500-02109-0 |url=https://archive.org/details/vikingsamerica00wahl }}</ref> | |||

| ===Western trade and decline=== | |||

| Not knowing whether the old Norse civilization remained in Greenland or not—and worried that if it did, it would still be ] 200 years after the ]n homelands had experienced the ]—a joint merchant-clerical expedition led by the Norwegian missionary ] was sent to Greenland in 1721. Though this expedition found no surviving Europeans, it marked the beginning of Denmark's assertion of sovereignty over the island; see ]. | |||

| There is evidence of Norse trade with the natives (called the {{lang|non|]jar}} by the Norse). The Norse would have encountered both ] (the ], related to the Algonquin) and the ], the ancestors of the ]. The ] had withdrawn from Greenland before the Norse settlement of the island. Items such as comb fragments, pieces of iron cooking utensils and chisels, chess pieces, ship ], carpenter's planes, and oaken ship fragments used in Inuit boats have been found far beyond the traditional range of Norse colonization. A small ] statue that appears to represent a ] has also been found among the ruins of an Inuit community house.<ref name="TVA" /> | |||

| ] (900 to 1500)]] | |||

| The settlements began to decline in the 14th century. The Western Settlement was abandoned around 1350, and the last bishop at Garðar died in 1377.<ref name="TVA" /> After a marriage was recorded in 1408, no written records mention the settlers. It is probable that the Eastern Settlement was defunct by the late 15th century. The most recent ] date found in Norse settlements as of 2002 was 1430 (±15 years).<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Dugmore |first1=Andrew J. |last2=Keller |first2=Christian |last3=McGovern |first3=Thomas H. |date=2007 |title=Norse Greenland Settlement: Reflections on Climate Change, Trade, and the Contrasting Fates or Human Settlements in the North Atlantic Islands |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/40316683 |journal=Arctic Anthropology |volume=44 |issue=1 |pages=12–36 |doi=10.1353/arc.2011.0038 |jstor=40316683 |pmid=21847839 |s2cid=10030083 |issn=0066-6939 |access-date=27 February 2022 |archive-date=27 February 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220227031758/https://www.jstor.org/stable/40316683 |url-status=live }}</ref> Several theories have been advanced to explain the decline. | |||

| The ] of this period would have made travel between Greenland and Europe, as well as farming, more difficult; although seal and other hunting provided a healthy diet, there was more prestige in cattle farming, and there was increased availability of farms in Scandinavian countries depopulated by famine and ] epidemics.<ref name="www.spiegel.de">{{cite web |last=Stockinger |first=Günther |title=Archaeologists Uncover Clues to Why Vikings Abandoned Greenland |url=http://www.spiegel.de/international/zeitgeist/archaeologists-uncover-clues-to-why-vikings-abandoned-greenland-a-876626.html |publisher=] Online |date=10 January 2012 |access-date=12 January 2013 |archive-date=28 September 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190928002823/https://www.spiegel.de/international/zeitgeist/archaeologists-uncover-clues-to-why-vikings-abandoned-greenland-a-876626.html |url-status=live }}</ref> In addition, Greenlandic ivory may have been supplanted in European markets by cheaper ivory from Africa.<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| ==Vinland and L'Anse aux Meadows== | |||

| | last= Seaver | first= Kirsten A. | title= Desirable Teeth: the Medieval Trade in Arctic and African Ivory | journal= Journal of Global History | volume= 4 | number= 2 | date= 2009 | pages= 271–292 | doi=10.1017/S1740022809003155 | publisher= Cambridge University Press | |||

| {{main|Vinland}}{{main|L'Anse aux Meadows}} | |||

| | s2cid= 153720935 | url= https://zenodo.org/record/891057 }}</ref> Despite the loss of contact with the Greenlanders, the Norwegian-Danish ] continued to consider Greenland a possession. | |||

| According to the Icelandic sagas ("]" and the "]"—chapters of the ] and the ]), the Norse started to explore lands to the west of Greenland only a few years after the Greenland settlements were established. In 985 while sailing from Iceland to Greenland with a migration fleet consisting of 400-700 settlers<ref name=ROBW/><ref name=NM2/> and 25 other ships (14 of which completed the journey), a merchant named ] was blown off course and after three days sailing he sighted land west of the fleet. Bjarni was only interested in finding his father's farm, but he described his discovery to ] who explored the area in more detail and planted a small settlement fifteen years later.<ref name=ROBW/> | |||

| Not knowing whether the old Norse civilization remained in Greenland or not—and worried that if it did, it would still be ] 200 years after the Scandinavian homelands had undergone the ]—a joint merchant-clerical expedition led by the Norwegian missionary ] was sent to Greenland in 1721.<ref name="Nedkvitne2018">{{cite book |last1=Nedkvitne |first1=Arnved |title=Norse Greenland: Viking Peasants in the Arctic |year=2018 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-351-25958-3 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Xs5wDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT14 |access-date=19 May 2022 |archive-date=2 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502033137/https://books.google.com/books?id=Xs5wDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT14 |url-status=live }}</ref> Though this expedition found no surviving Europeans, it marked the beginning of ] over the island.<ref name="Stern2021">{{cite book |last1=Stern |first1=Pamela |title=The Inuit World |year=2021 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-000-45613-4 |pages=179–182 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Y85JEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT179 |access-date=19 May 2022 |archive-date=2 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502033135/https://books.google.com/books?id=Y85JEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT179 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The sagas describe three separate areas discovered during this exploration: ], which means "land of the flat stones"; ], "the land of forests", definitely of interest to settlers in Greenland where there were few trees; and ], which recent linguistic evidence identifies as "the land of meadows", found somewhere south of Markland. It was in Vinland that the settlement described in the sagas was planted. | |||

| === Climate and Norse Greenland === | |||

| All four of Erik the Red's children were to visit the North American continent, his sons Leif, Thorvald and Thorstein and their sister Freydis. One of the sons, Thorvald , died there. | |||

| Norse Greenlanders were limited to scattered fjords on the island that provided a spot for their animals (such as cattle, sheep, goats, dogs, and cats) to be kept and farms to be established.<ref name="Pringle1997">{{Cite journal|last=Pringle|first=Heather|date=14 February 1997|title=Death in Norse Greenland|journal=Science|language=en|volume=275|issue=5302|pages=924–926|doi=10.1126/science.275.5302.924|s2cid=161540120|issn=0036-8075}}</ref><ref name="DugmoreMcGovern2012">{{Cite journal|last1=Dugmore|first1=Andrew J.|last2=McGovern|first2=Thomas H.|last3=Vésteinsson|first3=Orri|last4=Arneborg|first4=Jette|last5=Streeter|first5=Richard|last6=Keller|first6=Christian|date=2012|title=Cultural adaptation, compounding vulnerabilities and conjunctures in Norse Greenland|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America|volume=109|issue=10|pages=3658–3663|doi=10.1073/pnas.1115292109|pmid=22371594|jstor=41507015|pmc=3309771|bibcode=2012PNAS..109.3658D|doi-access=free}}</ref> In these fjords, the farms depended upon stables ('']s'') to host their livestock in the winter, and routinely culled their herds so that they could survive the season.<ref name="Pringle1997" /><ref name="DugmoreMcGovern2012" /><ref name="Berglund1986">{{Cite journal|last=Berglund|first=Joel|date=1986|title=The Decline of the Norse Settlements in Greenland|journal=Arctic Anthropology|volume=23|issue=1/2|pages=109–135|jstor=40316106}}</ref> The coming warmer seasons meant that livestock were taken from their byres to pasture, the most fertile being controlled by the most powerful farms and the church.<ref name="DugmoreMcGovern2012" /><ref name="Berglund1986" /><ref name="McGovern1980">{{Cite journal|last=McGovern|first=Thomas H.|date=1980|title=Cows, Harp Seals, and Churchbells: Adaptation and Extinction in Norse Greenland|journal=Human Ecology|volume=8|issue=3|pages=245–275|doi=10.1007/bf01561026|jstor=4602559|bibcode=1980HumEc...8..245M |s2cid=53964845}}</ref> What was produced by livestock and farming was supplemented with subsistence hunting of mainly seal and caribou as well as walrus for trade.<ref name="Pringle1997" /><ref name="DugmoreMcGovern2012" /><ref name="Berglund1986" /> The Norse mainly relied on the ''Nordrsetur'' hunt, a communal hunt of migratory ]s in the spring.<ref name="Pringle1997" /><ref name="McGovern1980" /> | |||

| Trade was highly important to the Greenland Norse and they relied on imports of lumber due to the barrenness of Greenland. In turn they exported goods such as walrus ivory and hide, live polar bears, and narwhal tusks.<ref name="Berglund1986" /><ref name="McGovern1980" /> Ultimately these setups were vulnerable as they relied on migratory patterns created by climate as well as the viability of the few fjords on the island.<ref name="DugmoreMcGovern2012" /><ref name="McGovern1980" /> A portion of the time the Greenland settlements existed was during the ] and the climate was, overall, becoming cooler and more humid.<ref name="Pringle1997" /><ref name="DugmoreMcGovern2012" /><ref name="Berglund1986" /> As climate began to cool and humidity began to increase, this brought more storms, longer winters and shorter springs, and affected the migratory patterns of the harp seal.<ref name="Pringle1997" /><ref name="DugmoreMcGovern2012" /><ref name="Berglund1986" /><ref name="McGovern1980" /> Pasture space began to dwindle and fodder yields for the winter became much smaller. This combined with regular herd culling made it hard to maintain livestock, especially for the poorest of the Greenland Norse.<ref name="Pringle1997" /> Closer to the Eastern Settlement, temperatures remained stable but a prolonged drought reduced fodder production.<ref name="Zhao 22">{{cite journal | last1=Zhao | first1=Boyang | last2=Castañeda | first2=Isla S. | last3=Salacup | first3=Jeffrey M. | last4=Thomas | first4=Elizabeth K. | last5=Daniels | first5=William C. | last6=Schneider | first6=Tobias | last7=de Wet | first7=Gregory A. | last8=Bradley | first8=Raymond S. | title=Prolonged drying trend coincident with the demise of Norse settlement in southern Greenland | journal=Science Advances | publisher=American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) | volume=8 | issue=12 | date=25 March 2022 | pages=eabm4346 | issn=2375-2548 | doi=10.1126/sciadv.abm4346 | pmid=35319972 | pmc=8942370 | bibcode=2022SciA....8M4346Z }}</ref> In spring, the voyages to where migratory harp seals could be found became more dangerous due to more frequent storms, and the lower population of harp seals meant that ''Nordrsetur'' hunts became less successful, making subsistence hunting extremely difficult.<ref name="Pringle1997" /><ref name="DugmoreMcGovern2012" /> The strain on resources made trade difficult, and as time went on, Greenland exports lost value in the European market due to competing countries and the lack of interest in what was being traded.<ref name="McGovern1980" /> Trade in elephant ivory began competing with the trade in walrus tusks that provided income to Greenland, and there is evidence that walrus over-hunting, particularly of the males with larger tusks, led to walrus population declines.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Barrett|first1=James H.|last2=Boessenkool|first2=Sanne|last3=Kneale|first3=Catherine J.|last4=O'Connell|first4=Tamsin C.|author4-link=Tamsin O'Connell|last5=Star|first5=Bastiaan|date=1 February 2020|title=Ecological globalisation, serial depletion and the medieval trade of walrus rostra|journal=Quaternary Science Reviews|volume=229|page=106122|doi=10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.106122|bibcode=2020QSRv..22906122B|issn=0277-3791|doi-access=free|hdl=2262/91845|hdl-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| In addition, it seemed that the Norse were unwilling to integrate with the ] of Greenland, through either marriage or culture. There is evidence of contact as seen through the Thule archaeological record, including ivory depictions of the Norse as well as bronze and steel artifacts. In the 20th century, there was little evidence for Thule artifacts among Norse habitations,<ref name="Pringle1997" /> however it is now known that Thule artifacts are found among Norse habitations, indicating that both groups acquired material goods from each other.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Paterson |first1=Alistair |title=A Millennium of Cultural Contact |date=16 June 2016 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-315-43572-5 |page=57 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=weFmDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA57 |language=en |access-date=3 July 2023 |archive-date=4 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230704004454/https://books.google.com/books?id=weFmDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA57 |url-status=live }}</ref> The older research posited that it was not climate change alone that led to Norse decline, but also their unwillingness to adapt.<ref name="Pringle1997" /> For example, if the Norse had decided to focus their subsistence hunting on the ] (which could be hunted year round, though individually), and decided to reduce or do away with their communal hunts, food would have been much less scarce during the winter season.<ref name="DugmoreMcGovern2012" /><ref name="Berglund1986" /><ref name="McGovern1980" /><ref name="McGovern1999">{{Cite journal|last=McGovern|first=Thomas H.|date=1991|title=Climate, Correlation, and Causation in Norse Greenland|journal=Arctic Anthropology|volume=28|issue=2|pages=77–100|jstor=40316278}}</ref> Also, had Norse individuals used skins instead of wool for their clothing, they would have fared better nearer to the coast, and would not have been as confined to the fjords.<ref name="DugmoreMcGovern2012" /><ref name="Berglund1986" /><ref name="McGovern1980" /> | |||

| However, more recent research has shown that the Norse did try to adapt in their own ways. This included increased subsistence hunting. A significant number of bones of marine animals can be found at the settlements, suggesting increased hunting with the absence of farmed food. In addition, pollen records show that the Norse did not always devastate the small forests and foliage, as previously thought. Instead they ensured that overgrazed or overused sections were given time to regrow and moved to other areas. Norse farmers also attempted to adapt; with the increased need for winter fodder and smaller pastures, they would self-fertilize their lands to try to keep up with the new demands caused by the changing climate.<ref name="Kintisch2016">{{cite web |last1=Kintisch |first1=Eli |title=Why did Greenland's Vikings disappear? |url=https://www.science.org/content/article/why-did-greenland-s-vikings-disappear |website=Science.org |access-date=21 May 2022 |language=en |date=10 November 2016 |archive-date=11 November 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211111131631/https://www.science.org/content/article/why-did-greenland-s-vikings-disappear |url-status=live }}</ref> However, even with these attempts, climate change was not the only thing putting pressure on the Greenland Norse. The economy was changing, and the exports they relied on were losing value.<ref name="McGovern1980" /> Current research suggests that the Norse were unable to maintain their settlements because of economic and climatic change happening at the same time.<ref name="Kintisch2016" /> | |||

| A 2022 study indicates that gravitational effects from a readvance of the Southern Greenland Ice Sheet caused a relative sea level rise of "up to ~3.3 m outside the glaciation zone during Viking settlement, producing shoreline retreat of hundreds of meters. Sea-level rise was progressive and encompassed the entire Eastern Settlement. Moreover, pervasive flooding would have forced abandonment of many coastal sites. These processes likely contributed to the suite of vulnerabilities that led to Viking abandonment of Greenland. Sea-level change thus represents an integral, missing element of the Viking story."<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Borreggine |first1=Marisa |last2=Latychev |first2=Konstantin |last3=Coulson |first3=Sophie |last4=Powell |first4=Evelyn |last5=Mitrovica |first5=Jerry |last6=Milne |first6=Glenn |last7=Alley |first7=Richard |title=Sea-level rise in Southwest Greenland as a contributor to Viking abandonment |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |date=17 April 2023 |volume=120 |issue=17 |pages=e2209615120 |doi=10.1073/pnas.2209615120 |pmid=37068242 |s2cid=258189345 |pmc=10151458 |bibcode=2023PNAS..12009615B }}</ref> | |||

| ==Vinland sagas== | |||

| {{Main article|Vinland|L'Anse aux Meadows}} | |||

| According to the ]{{mdash}}'']'',<ref>{{cite news |last=Sephton |first=J. |url=http://sagadb.org/eiriks_saga_rauda.en |title=The Saga of Erik the Red |year=1880 |newspaper=Icelandic Saga Database |access-date=11 August 2010 |archive-date=4 May 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160504211747/http://sagadb.org/eiriks_saga_rauda.en |url-status=live }}</ref> plus chapters of the '']'' and the '']''{{mdash}}the Norse started to explore lands to the west of Greenland only a few years after the Greenland settlements were established. In 985, while sailing from Iceland to Greenland with a migration fleet consisting of 400–700 settlers<ref name="ROBW" /> and 25 other ships (14 of which completed the journey), a merchant named ] was blown off course, and after three days' sailing he sighted land west of the fleet. Bjarni was only interested in finding his father's farm, but he described his findings to ] who explored the area in more detail and planted a small settlement fifteen years later.<ref name="ROBW" /> | |||

| The sagas describe three separate areas that were explored: ], which means "land of the flat stones"; ], "the land of forests", definitely of interest to settlers in Greenland where there were few trees; and ], "the land of wine", found somewhere south of Markland. It was in Vinland that the settlement described in the sagas was founded. | |||

| Markland was first mentioned in the ] area in 1345 by the Milanese friar ]. He probably derived it from oral sources in Genoa.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Chiesa|first=Paolo|date=2021|title=Marckalada: The First Mention of America in the Mediterranean Area (c. 1340)|url=https://doi.org/10.1080/00822884.2021.1943792|journal=Terrae Incognitae|volume=53|issue=2|pages=88–106|doi=10.1080/00822884.2021.1943792|hdl=2434/860960|issn=0082-2884|s2cid=236457428|hdl-access=free|access-date=17 September 2021|archive-date=2 May 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502033137/https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00822884.2021.1943792|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Leif's winter camp=== | ===Leif's winter camp=== | ||

| ], Vinland (]), ], (]) and ] (]) travelled by different characters in the ], mainly ] and ]. Modern English versions of the Norse names.]] | |||

| {{Cleanup-section|date=August 2008}} | |||

| Using the routes, landmarks, ], rocks, and winds Bjarni described to him Leif sailed |

Using the routes, landmarks, ], rocks, and winds that Bjarni had described to him, Leif sailed from Greenland westward across the Labrador Sea, with a crew of 35—sailing the same ] Bjarni had used to make the voyage. He described Helluland as "level and wooded, with broad white beaches wherever they went and a gently sloping shoreline."<ref name="ROBW" /> Leif and others had wanted his father, Erik the Red, to lead this expedition and talked him into it. However, as Erik attempted to join his son Leif on the voyage towards these new lands, he fell off his horse as it slipped on the wet rocks near the shore; thus he was injured and stayed behind.<ref name="ROBW" /> | ||

| Sometime around AD 1000, Leif spent the winter, when one day his foster father ] found what the saga describes as "wine-berries." ], ], and ] all grew wild in the area. There are varying explanations for Leif apparently describing ] as "grapes." | |||

| Leif spent another winter at "]" without conflict, and sailed back to ] in Greenland to assume filial duties to his father. | |||

| ===Thorvald's voyage=== | ===Thorvald's voyage=== | ||

| A couple of years later,<ref name=chronology>See chronology {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211021220517/https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03972-8/figures/6 |date=21 October 2021 }}.</ref> Leif's brother ] sailed with a crew of 30 men to Vinland and spent the following winter at Leif's camp. In the spring, Thorvald attacked nine of the native people who were sleeping under three skin-covered ]s. The ninth victim escaped and soon came back to the Norse camp with a force. Thorvald was killed by an arrow that succeeded in passing through the ]. Although brief hostilities ensued, the Norse explorers stayed another winter and left the following spring. Subsequently, another of Leif's brothers, Thorstein, sailed to the New World to retrieve his dead brother's body, but he died before leaving Greenland.<ref name="ROBW" /> | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Karlsefni's expedition=== | ===Karlsefni's expedition=== | ||

| A few years later,<ref name=chronology/> ], also known as "Thorfinn the Valiant", supplied three ] with livestock and 160 men and women (although another source sets the number of settlers at 250). After a cruel winter, he headed south and landed at '']''.<ref name="MagnussonPálsson1973">{{cite book |last1=Magnusson |first1=Magnus |last2=Pálsson |first2=Hermann |author1-link=Magnus Magnusson |title=The Vinland Sagas: The Norse Discovery of America |year=1973 |publisher=Penguin UK |isbn=978-0-14-190698-0 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mkTKZMwm2YsC&pg=PT119 |page=119 |access-date=18 May 2022 |archive-date=2 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502033135/https://books.google.com/books?id=mkTKZMwm2YsC&pg=PT119 |url-status=live }}</ref> He later moved to ''Straumsöy'', possibly because the current was stronger there. A sign of peaceful relations between the ] and the Norsemen is noted here. The two sides ]ed with furs and ] skins for milk and red cloth,<ref>{{harvnb|Magnusson|Pálsson|1973|p=30}}</ref> which the natives tied around their heads as a sort of ]. | |||

| {{POV-section|date=August 2008}} | |||

| {{Cleanup-section|date=August 2008}} | |||

| It was in 1009 that ], also known as "Thorfinn the Valient", supplied three ] with livestock and 160 men and women<ref name=NM2>Oxenstierna, Eric; ''The Norsemen'' (1965), 320 pages, New York Graphic Soc.: ISBN 1122216319</ref> (although another source sets the number of settlers at 250). After a cruel winter, he headed south and landed at ''Straumfjord'', but later moved to ''Straumsöy'' since the current was stronger there. In that small landlocked bay, the first sign of peaceful relations between the ]s and the Norsemen was noted. The two sides ]ed with furs and ] skins for ] and red cloth, which the natives tied around their heads as a sort of ]. | |||

| There are conflicting stories but one account states that a bull belonging to Karlsefni came storming out of the wood, so frightening the natives that they ran to their skin-boats |

There are conflicting stories but one account states that a bull belonging to Karlsefni came storming out of the wood, so frightening the natives that they ran to their skin-boats and rowed away. They returned three days later, in force. The natives used catapults, hoisting "a large sphere on a pole; it was dark blue in color"<ref name="HansenCurtis2016">{{cite book |last1=Hansen |first1=Valerie |last2=Curtis |first2=Ken |title=Voyages in World History |year=2016 |publisher=Cengage Learning |isbn=978-1-305-88841-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VckaCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA295 |page=295 |access-date=18 May 2022 |archive-date=2 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502033137/https://books.google.com/books?id=VckaCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA295 |url-status=live }}</ref> and about "the size of a sheep's stomach",<ref>{{harvnb|Magnusson|Pálsson|1973|p=187}}</ref> which flew over the heads of the men and "made an ugly din when it struck the ground".<ref name="HansenCurtis2016" /> | ||

| |title=The Vinland Sagas | |||

| |first1=Magnus | |||

| |last1=Magnusson | |||

| |first2=Hermann | |||

| |last2=Palsson | |||

| |publisher=Penguin Books | |||

| |isbn=9780140441543 | |||

| |year=1965 | |||

| }}</ref> which flew over the heads of the men and made an ugly din when it hit the ground.<ref name=VS/> The Norsemen retreated. ]'s half-sister ] was pregnant, and unable to keep up with the retreating Norsemen. She called out to them to stop fleeing from "such pitiful wretches", adding that if she had weapons, she could do better than that. Freydís seized the sword belonging to a man who had been killed by the natives (with a flintstone in his head) and turned to defend herself. She pulled one of her breasts out of her bodice and struck it with the sword, frightening the natives, who fled.<ref name=VS/> | |||

| The Norsemen retreated. Leif Erikson's half-sister ] was pregnant and unable to keep up with the retreating Norsemen. She called out to them to stop fleeing from "such pitiful wretches", adding that if she had weapons, she could do better than that. Freydís seized the sword belonging to a man who had been killed by the natives. She pulled one of her breasts out of her bodice and slapped it with the sword, frightening the natives, who fled.<ref name="BalkunImbarrato2016">{{cite book |last1=Balkun |first1=Mary McAleer |last2=Imbarrato |first2=Susan C. |title=Women's Narratives of the Early Americas and the Formation of Empire |year=2016 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |isbn=978-1-137-54320-2 |page=21 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=d3hhCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT21 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220518185559/https://books.google.com/books?id=d3hhCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT21 |url-status=dead |archive-date=18 May 2022 }}</ref><ref name="Gardeła2021">{{cite book |last1=Gardeła |first1=Leszek |title=Women and Weapons in the Viking World: Amazons of the North |date=2021 |publisher=Oxbow Books |isbn=978-1-78925-668-0 |page=93 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PvE1EAAAQBAJ&pg=PA93 |access-date=18 May 2022 |archive-date=2 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502033136/https://books.google.com/books?id=PvE1EAAAQBAJ&pg=PA93 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| As noted, the contacts between the two ]s were not always hostile given that there are records of a renewed trade between the two. In addition, different types of Norse materials have been excavated in several ]. | |||

| == |

==Historiography== | ||

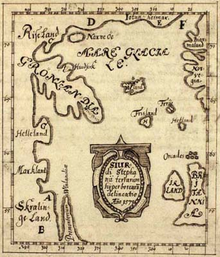

| ] showing Latinized Norse placenames in North America:<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.myoldmaps.com/renaissance-maps-1490-1800/4316-skalholt-map/4316-skalholt-map.pdf |title=Skálholt Map |date= |accessdate=13 March 2021 |archive-date=7 August 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190807191604/http://www.myoldmaps.com/renaissance-maps-1490-1800/4316-skalholt-map/4316-skalholt-map.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><br /> | |||

| ] | |||

| • Land of the '']'' (a ])<br /> | |||

| Evidence suggests that sporadic voyages to Markland for forages, timber, and trade with the native locals could have lasted as long as 400 years.<ref> Schledermann, Peter. 1996. Voices in Stone. A Personal Journey into the Arctic Past. Komatik Series no. 5. Calgary: The Arctic Institute of North America and the University of Calgary.</ref><ref> Sutherland, Patricia. 2000. “The Norse and Native Norse Americans”. In William W. Fitzhugh and Elisabeth I. Ward, eds., Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga, 238-247. Washington, DC: The Smithsonian Institution.</ref> Evidence of continuing trips includes the ], a Norwegian coin from King ]'s reign (1066-80) found in a Native American archaeological site in ], United States, suggesting an exchange between the Norse and the Native Americans late in or after the 11th century; and an entry in the Icelandic Annals from 1347 which refers to a small Greenlandic vessel with a crew of eighteen that arrived in Iceland while attempting to return to Greenland from Markland with a load of timber.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.mnh.si.edu/vikings/voyage/subset/markland/archeo.html | title= Markland and Helluland |accessdate= 2008-08-14 |author= |date= |year= |month= |format= |work= |publisher= Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History |pages= Archeology page and following |quote= }}</ref> | |||

| • ]<br /> | |||

| • ] (])<br /> | |||

| • ] (the ])<br /> | |||

| • Land of the '']'' (location undetermined)<br /> | |||

| • Promontory of ] (the ])]] | |||

| For centuries, it remained unclear whether the Icelandic stories represented real voyages by the Norse to North America. Although the idea of Norse voyages to, and a colony in, North America was discussed by Swiss scholar ] in his book ''Northern Antiquities'' (English translation 1770),<ref name="Mallet1770">{{cite book |last1=Mallet |first1=Paul Henri |title=Description of the manners, &c. of the ancient Danes |year=1770 |volume=I |publisher=T. Carnan and Company |pages=282–289 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=K9ZCAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA282 |quote=Hitherto we have seen the Norwegians only making slight efforts to establish themselves in Vinland. The year after Thorstein's death proved more favourable to the design of settling a colony. |access-date=20 May 2022 |archive-date=2 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502033136/https://books.google.com/books?id=K9ZCAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA282 |url-status=live }}</ref> the sagas first gained widespread attention in 1837 when the Danish antiquarian ] revived the idea of a Viking presence in North America.<ref name="Watts2020">{{cite book |last1=Watts |first1=Edward |title=Colonizing the Past: Mythmaking and Pre-Columbian Whites in Nineteenth-Century American Writing |year=2020 |publisher=University of Virginia Press |isbn=978-0-8139-4388-6 |pages=242–243 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Thq1DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT243 |chapter=The Norse Forefathers of the American Empire |quote=Translated to English and published on both sides of the Atlantic, Rafn's book, the interpretive translation of the Icelandic sagas originally transcribed by Snorri Sturluson and other Skaldic poets in the fourteenth century, catalyzed a transatlantic fascination with all things Viking. This would encompass more than the expected primordial land-based fantasy of a Norse origin. It also catalyzed a more durable blood-based fabrication that pushed the American appropriation of Gothic Anglo-Saxon identity deeper into the legendary past to its fictional roots in Scandinavian Teutonism by designating Anglo-Saxonism as a subculture of Norse Teutonism. |archive-date=2 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502033136/https://books.google.com/books?id=Thq1DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT242 |url-status=live }}</ref> North America, by the name ], first appeared in written sources in a work by ] from approximately 1075.<ref name="Whittock2018">{{cite book |last1=Whittock |first1=Martyn |title=Tales of Valhalla |year=2018 |publisher=Simon and Schuster |isbn=978-1-68177-912-6 |page=9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YbdTDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT9 |archive-date=2 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502033137/https://books.google.com/books?id=YbdTDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT9 |url-status=live }}</ref> The most important works about North America and the early Norse activities there, namely the ], were recorded in the 13th and 14th centuries. In 1420, some ] captives and their kayaks were taken to ].<ref name="Weaver2014">{{cite book |last1=Weaver |first1=Jace |title=The Red Atlantic: American Indigenes and the Making of the Modern World, 1000–1927 |date=2014 |publisher=UNC Press Books |isbn=978-1-4696-1439-7 |page=37 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=08IBAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA37 |archive-date=2 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502033138/https://books.google.com/books?id=08IBAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA37 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Plank2020">{{cite book |last1=Plank |first1=Geoffrey |title=Atlantic Wars: From the Fifteenth Century to the Age of Revolution |year=2020 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-086046-2 |page=5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EurkDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA5 |archive-date=2 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502033138/https://books.google.com/books?id=EurkDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA5 |url-status=live }}</ref> The Norse sites were depicted in the ], made by an Icelandic teacher in 1570 and depicting part of northeastern North America and mentioning Helluland, Markland and Vinland.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Ingstad|first1=Helga|last2=Ingstad|first2=Anne Stine|title=The Viking Discovery of America: The Excavation of a Norse Settlement in L'Anse Aux Meadows, Newfoundland|year=2001|publisher=Breeakwater Books|isbn=978-0816047161|page=111|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Gj-I5hdpzGoC&pg=PA111|archive-date=2 May 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502033138/https://books.google.com/books?id=Gj-I5hdpzGoC&pg=PA111|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ] listed ] site in Newfoundland, Canada. Archaeological evidence demonstrates that iron working, carpentry, and boat repair were conducted at the site.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Wallace |first1=Birgitta |title=L'Anse aux Meadows |url=https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/lanse-aux-meadows |website=The Canadian Encyclopedia |access-date=4 June 2020 |archive-date=27 February 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210227064113/https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/lanse-aux-meadows |url-status=live }}</ref>]] | |||

| The question was definitively settled in the 1960s when a Norse settlement was excavated at ] in ] by the outdoorsman and author ] and his wife Dr. ], an archaeologist. The location of the various lands described in the sagas is still unclear however. Many historians identify Helluland with ] and Markland with ]. The location of Vinland is a thornier question. Most believe that the L'Anse aux Meadows settlement is the Vinland settlement described in the sagas; others argue that the sagas depict Vinland as being warmer than Newfoundland and that it therefore lay further south. There are still many questions remaining and only new ] findings can supply more information. | |||

| Evidence of the Norse west of Greenland came in the 1960s when archaeologist ] and author ] excavated a Norse site at ] in ]. They found a bronze, ring-headed pin like those the Norse used to fasten their cloaks inside the cooking pit of one of the larger dwellings. A stone oil lamp and a small ], used as the flywheel of a handheld spindle, were found inside another building. A fragment of a bone needle believed to have been used for knitting was discovered in the firepit of a third dwelling. A small, decorated brass fragment, once ], was also discovered. Much ] formed as a by-product from the smelting and working of iron was found on the site along with many iron boat nails or rivets.<ref name="Mueller-Vollmer2022">{{cite book |last1=Mueller-Vollmer |first1=Tristan |last2=Wolf |first2=Kirsten |title=Vikings: An Encyclopedia of Conflict, Invasions, and Raids |year=2022 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1-4408-7730-8 |pages=29–30 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MtljEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA29 |archive-date=2 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502033142/https://books.google.com/books?id=MtljEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA29 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In 2012, Canadian researchers identified possible signs of Norse outposts in ] at ] on ], as well as on Nunguvik, Willows Island, and ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2012/10/121019-viking-outpost-second-new-canada-science-sutherland/ |title=Evidence of Viking Outpost Found in Canada |access-date=28 January 2013 |last=Pringle |first=Heather |date=19 October 2012 |work=National Geographic News |publisher=] |archive-date=17 May 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160517220110/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2012/10/121019-viking-outpost-second-new-canada-science-sutherland/ |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=Vikings and Native Americans |journal=National Geographic |date=November 2012 |first=Heather |last=Pringle |volume=221 |issue=11 |url=http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2012/11/vikings-and-indians/pringle-text |access-date=28 January 2013 |archive-date=19 January 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180119110451/http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2012/11/vikings-and-indians/pringle-text |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |author=The Nature of Things |url=http://www.cbc.ca/natureofthings/episode/the-norse-an-arctic-mystery.html |title=The Norse: An Arctic Mystery |access-date=29 January 2013 |author-link=The Nature of Things |date=22 November 2012 |publisher=] |archive-date=27 November 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121127184750/http://www.cbc.ca/natureofthings/episode/the-norse-an-arctic-mystery.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Unusual fabric cordage found on Baffin Island in the 1980s and stored at the ] was identified in 1999 as possibly of Norse manufacture; that discovery led to more comprehensive exploration of the Tanfield Valley archaeological site for points of contact between Norse Greenlanders and the indigenous ].<ref>{{cite conference | first =Patricia | last =Sutherland | author-link =Patricia Sutherland | title =Strands of Culture Contact: Dorset-Norse Interactions in the Canadian Eastern Arctic | book-title =Identities and Cultural Contacts in the Arctic: Proceedings from a Conference at the Danish National Museum, Copenhagen, 30 November to 2 December 1999 | editor1-first =Martin | editor1-last =Appelt | editor2-first =Joel | editor2-last =Berglund | editor3-first =Hans Christian | editor3-last =Gulløv | pages =159–169 | publisher =The Danish National Museum & Danish Polar Center | date =2000 | location =Copenhagen, Denmark | url =https://www.historymuseum.ca/learn/research/resources-for-scholars/essays/dorset-norse-interactions-in-the-canadian-eastern-arctic/ | access-date =19 December 2018 | archive-date =4 December 2018 | archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20181204073956/https://www.historymuseum.ca/learn/research/resources-for-scholars/essays/dorset-norse-interactions-in-the-canadian-eastern-arctic/ | url-status =live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url =https://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/archeo/helluland/str0301e.html | title =Strangers, Partners, Neighbors? Helluland Archaeology Project: Recent Finds | publisher =Canadian Museum of History | access-date =19 December 2018 | archive-date =3 December 2018 | archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20181203230055/https://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/archeo/helluland/str0301e.html | url-status =live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Aftermath== | |||

| For some centuries after ]' voyages opened the Americas to large-scale colonization by Europeans, it was unclear whether these stories represented real voyages by the Norse to North America. The sagas were first taken seriously when in 1837 the Danish antiquarian ] pointed out the possibility for a Norse settlement in or voyages to North America. | |||

| ] in ]]] | |||

| ] is the first historian in the ] that referred to the ] (by the name ]). The ] remain the most important written sources about the early Norse activities in America. Purported runestones have been found in North America (e.g. the ], the ], and ]) that are thought by some to be artifacts from further Norse exploration. However, these runestones are generally considered to be forgeries. There is a map depicting North America (the ]) that some believe is related to Norse exploration, though it is almost certainly a hoax.{{Fact|date=August 2008}} | |||

| In 2021, some wood from L'Anse aux Meadows that was chopped by an axe was dated to 1021, thus providing for the first time a certain date with regard to the Norse presence at the site.<ref name="KuitemsEtAl">{{Cite journal|last1=Kuitems|first1=Margot|last2=Wallace|first2=Birgitta L.|last3=Lindsay|first3=Charles|last4=Scifo|first4=Andrea|last5=Doeve|first5=Petra|last6=Jenkins|first6=Kevin|last7=Lindauer|first7=Susanne|last8=Erdil|first8=Pınar|last9=Ledger|first9=Paul M.|last10=Forbes|first10=Véronique|last11=Vermeeren|first11=Caroline|date=20 October 2021|title=Evidence for European presence in the Americas in AD 1021|journal=Nature|volume=601 |issue=7893 |language=en|pages=388–391|doi=10.1038/s41586-021-03972-8|pmid=34671168|pmc=8770119 |bibcode=2022Natur.601..388K |s2cid=239051036|issn=1476-4687|quote=Our result of AD 1021 for the cutting year constitutes the only secure calendar date for the presence of Europeans across the Atlantic before the voyages of Columbus. Moreover, the fact that our results, on three different trees, converge on the same year is notable and unexpected. This coincidence strongly suggests Norse activity at L'Anse aux Meadows in AD 1021. In addition, our research demonstrates the potential of the AD 993 anomaly in atmospheric 14C concentrations for pinpointing the ages of past migrations and cultural interactions. }}</ref> | |||

| == |

==Pseudohistory== | ||

| Purported ]s have been found in North America, most famously the ]. These are generally considered forgeries or misinterpretations of ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kolodny |first=Annette |author-link=Annette Kolodny |date=December 2003 |title=Fictions of American Prehistory: Indians, Archeology, and National Origin Myths |url=https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/4/article/51011 |journal=] |volume=75 |issue=4 |pages=693–721 |doi=10.1215/00029831-75-4-693 |issn=0002-9831}}</ref> There are many claims of Norse colonization in New England, none well founded. | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ]'s book ''Norse America'', published in 2021, develops his thesis that the "fleeting and ill-documented" idea that Vikings "discovered America" quickly seduced Americans of northern European Protestant descent, some of whom went on to deliberately manufacture evidence to support it.<ref name="Campbell2021">{{cite book |last1=Campbell |first1=Gordon |title=Norse America: The Story of a Founding Myth |year=2021 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-886155-3 |pages=27, 212 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pHEhEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA212 |archive-date=2 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502034643/https://books.google.com/books?id=pHEhEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA212 |url-status=live }}</ref> There is no physical evidence of a Norse presence in North America except for the far east of Canada.<ref name="Rotella2007">{{cite journal |last=Rotella |first=Carlo |title=Pulp History |journal=Raritan |publisher=Rutgers University |pages=11–36 |date=Summer 2007 |volume=27 |issue=1}}</ref> Other so-called discoveries, mostly in the United States, have been rejected by scholars.<ref name="Kraft1989">{{cite journal |last1=Kraft |first1=Herbert C. |title=Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Indian/White Trade Relations in the Middle Atlantic and Northeast Regions |journal=Archaeology of Eastern North America |date=1989 |volume=17 |pages=1–29 |jstor=40914304 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/40914304 |issn=0360-1021}}</ref> Supposed physical evidence has been found to be deliberately falsified or historically baseless, often to promote a political agenda. Literary critic ] criticized attempts to evoke what she termed "plastic vikings". These were fictional characters treated as historical figures, but "depicted variously as heroic warriors and empire builders, barbarous berserker invaders, fighters for freedom, courageous explorers, would-be colonists, seamen and merchants, poets and saga men, glorious ancestors, bloodthirsty pagan pirates, and civilized Christian converts" depending on the speaker or author.<ref name="Watts2020 2243">{{cite book |last1=Watts |first1=Edward |title=Colonizing the Past: Mythmaking and Pre-Columbian Whites in Nineteenth-Century American Writing |year=2020 |publisher=University of Virginia Press |isbn=978-0-8139-4388-6 |page=243 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Thq1DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT243 |chapter=The Norse Forefathers of the American Empire}}</ref><ref name="Kolodny-2012">{{cite book |last1=Kolodny |first1=Annette |title=In Search of First Contact |year=2012 |publisher=Duke University Press |location=Durham, NC |page=204}}</ref> | |||

| Monuments claimed to be Norse include:<ref>{{Cite web |last=Klein |first=Christopher |date=23 November 2013 |title=Uncovering New England's Viking connections |url=https://www.bostonglobe.com/lifestyle/travel/2013/11/23/uncovering-new-england-viking-connections/JhxUdp7xvwZK8DjxqQ9cFO/story.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210125084907/https://www.bostonglobe.com/lifestyle/travel/2013/11/23/uncovering-new-england-viking-connections/JhxUdp7xvwZK8DjxqQ9cFO/story.html |archive-date=25 January 2021 |website=]}}</ref> | |||

| * ] in ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * The ] on ], from the ] in ] ] on display in the Alexandria Chamber of Commerce and Runestone Museum.]] | |||

| === Kensington Runestone === | |||

| {{main article|Kensington Runestone}} | |||

| In late 1898, Swedish immigrant Olof Öhman stated that he found this rune in ], while clearing land he had recently acquired.<ref name="Campbell2021173">{{cite book |last1=Campbell |first1=Gordon |title=Norse America: The Story of a Founding Myth |year=2021 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-886155-3 |page=173 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pHEhEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA173 |archive-date=2 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502034643/https://books.google.com/books?id=pHEhEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA173 |url-status=live }}</ref> He stated that the rune was lying face down and tangled in various roots near the crest of a small ] within an area of wetlands. After ] (1853–1916), professor of Scandinavian Languages and Literature in the Scandinavian Department at the ] analyzed the inscriptions, he declared the rune-stone to be a forgery and published a discrediting article in '']'' in 1910.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Breda |first=Olaus |date=1910 |title=Kensington-stenen |pages=65–80 |work=Symra}}</ref> Breda also forwarded copies of the inscription to various contemporary Scandinavian linguists and historians, such as ], ], ], ] and ]. They "unanimously pronounced the Kensington inscription a fraud and forgery of recent date".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Blegen |first=Theodore Christian |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/190744 |title=The Kensington rune stone; new light on an old riddle |date=1968 |publisher=Minnesota Historical Society |isbn=0-87351-044-5 |location=St. Paul |oclc=190744}}</ref> | |||

| ===Horsford's Norumbega=== | |||

| {{main article|Eben Norton Horsford#Viking}} | |||

| The nineteenth-century Harvard chemist ] connected the ] Basin to places described in the ]s and elsewhere, notably ].<ref name="Fleming1995">{{cite journal|author=Robin Fleming|title=Picturesque History and the Medieval in Nineteenth-Century America|journal=The American Historical Review|volume=100|issue=4|pages=1079–1082|year=1995|jstor=2168201|doi=10.1086/ahr/100.4.1061|author-link=Robin Fleming}}</ref> He published several books on the topic and had plaques, monuments, and statues erected in honor of the Norse.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Eben Norton Horsford|author2=Edward Henry Clement|title=The discovery of the ancient city of Norumbega: A communication to the president and council of the American Geographical Society at their special session in Watertown, November 21, 1889|url=https://archive.org/details/discoveryancien00yorkgoog|year=1890|publisher=Houghton, Mifflin|page=}}</ref> His work received little support from mainstream historians and archeologists at the time, and even less today.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Williams |first=Stephen |url=https://archive.org/details/fantasticarchaeo00will |title=Fantastic Archaeology: The Wild Side of North American Prehistory |date=1991 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-8122-8238-2 |location=Philadelphia |url-access=registration}}</ref><ref>Gloria Polizzotti Greis {{cite web |url=http://greisnet.com/needhist.nsf/VikingsontheCharles?OpenPage |title=Vikings on the Charles or The Strange Saga of Dighton Rock, Norumbega, and Rumford Double-Acting Baking Powder |access-date=18 February 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110716041144/http://greisnet.com/needhist.nsf/VikingsontheCharles?OpenPage |archive-date=16 July 2011 }}. Needham Historical Society</ref> | |||

| Other nineteenth-century writers, such as Horsford's friend ], in his ''A Sheaf of Papers'' (1875), and ], in his ''The Goths in New England'', seized upon such false notions of ] history also to promote the superiority of ] (as well as to oppose the ]). Such misuse of Viking history and imagery reemerged in the twentieth century among some groups promoting ].<ref>{{cite magazine |last=Regal |first=Brian |date=November–December 2019 |title=Everything Means Something in Viking |magazine=] |publisher=] |volume=43 |issue=6 |pages=44–47}}</ref> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| === Vinland Map === | |||

| {{Main|Vinland Map}}During the mid-1960s, ] announced the acquisition of a map purportedly drawn around 1440 that showed ] and a legend concerning Norse voyages to the region.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Cummings |first=Mike |date=1 September 2021 |title=Analysis unlocks secret of the Vinland Map — it's a fake |url=https://news.yale.edu/2021/09/01/analysis-unlocks-secret-vinland-map-its-fake |access-date=25 April 2022 |website=YaleNews |language=en |archive-date=15 September 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210915094955/https://news.yale.edu/2021/09/01/analysis-unlocks-secret-vinland-map-its-fake |url-status=live }}</ref> However certain experts doubted the authenticity of the map, based on linguistic and cartographic inconsistencies. Chemical analysis of the map's ink later shed further doubts on its authenticity. Scientific debate continued until in 2021 the university finally acknowledged that the Vinland Map is a forgery.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Yuhas |first=Alan |date=30 September 2021 |title=Yale Says Its Vinland Map, Once Called a Medieval Treasure, Is Fake |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/30/us/yale-vinland-map-fake.html |access-date=14 December 2021 |issn=0362-4331 |archive-date=21 November 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211121140732/https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/30/us/yale-vinland-map-fake.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Misattributed archeological findings === | |||

| Archeological findings in 2015 at ],<ref name="CBC2018">{{cite news|last=Bird|first=Lindsay|date=30 May 2018|title=Archeological quest for Codroy Valley Vikings comes up short – Report filed with province states no Norse activity found at dig site|publisher=CBC|url=http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/codroy-valley-vikings-report-1.4684066|access-date=18 June 2018|archive-date=3 June 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180603023906/http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/codroy-valley-vikings-report-1.4684066|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="TCP2018">{{cite news|last=McKenzie-Sutter|first=Holly|title=No Viking presence in southern Newfoundland after all, American researcher finds|publisher=The Canadian Press|url=http://www.timescolonist.com/no-viking-presence-in-southern-newfoundland-after-all-american-researcher-finds-1.23320719|url-status=dead|access-date=18 June 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180618203935/http://www.timescolonist.com/no-viking-presence-in-southern-newfoundland-after-all-american-researcher-finds-1.23320719|archive-date=18 June 2018}}</ref> on the southwest coast of Newfoundland, were originally thought to reveal evidence of a turf wall and the roasting of ] ore, and therefore a possible 10th century Norse settlement in Canada.<ref name="NatGeo">{{cite news|last=Strauss|first=Mark|date=31 March 2016|title=Discovery Could Rewrite History of Vikings in New World|newspaper=]|url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/03/160331-viking-discovery-north-america-canada-archaeology/|quote=Sarah Parcak, a National Geographic Fellow and "space archaeologist" who has used satellite imagery to locate lost Egyptian cities, temples, and tombs supported, in part, by a grant from the National Geographic Society led a team of archaeologists to Point Rosee last summer to conduct a "test excavation," a small-scale dig to search for initial evidence that the site merits further study.|access-date=22 May 2016|archive-date=21 April 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160421233343/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/03/160331-viking-discovery-north-america-canada-archaeology/|url-status=dead}}</ref> Findings from the 2016 excavation suggest the turf wall and the roasted bog iron ore discovered in 2015 were the result of natural processes.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Pringle|first1=Heather|date=March 2017|title=Vikings|url=http://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2017/03/vikings-ship-burials-battle-reenactor/|journal=National Geographic|volume=231|issue=3|access-date=14 May 2017|quote=During a small excavation in 2015, Parcak and her colleagues found what looked like a turf wall But a larger excavation last summer cast serious doubt on those interpretations, suggesting that the turf wall and accumulation of bog ore were the results of natural processes|archive-date=7 May 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170507122114/http://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2017/03/vikings-ship-burials-battle-reenactor/|url-status=dead}}</ref> The possible settlement was initially discovered through ] in 2014,<ref name="TWS2017">{{cite journal|last1=Kean|first1=Gary|date=30 September 2017|title=Update: Archaeologist thinks Codroy Valley may have once been visited by Vikings|url=http://www.thewesternstar.com/news/regional/update-archaeologist-thinks-codroy-valley-may-have-once-been-visited-by-vikings-121840/|journal=The Western Star|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180926100125/http://www.thewesternstar.com/news/regional/update-archaeologist-thinks-codroy-valley-may-have-once-been-visited-by-vikings-121840/|archive-date=26 September 2018|access-date=13 March 2018|quote=The expedition was documented by the PBS show "NOVA" in partnership with the BBC. The two-hour documentary, titled "Vikings Unearthed," will air on PBS }}</ref> and archaeologists excavated the area in 2015 and 2016.<ref name="TWS2017" /><ref name="NatGeo" /> ], one of the leading experts of Norse archaeology in North America and an expert on the Norse site at L'Anse aux Meadows, is unsure of the identification of Point Rosee as a Norse site.<ref name="CBC">{{cite news|last=Barry|first=Garrett|date=1 April 2016|title=Potential Viking site found in Newfoundland|publisher=]|url=http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/vikings-newfoundland-1.3515747/|access-date=1 January 2018|archive-date=3 April 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160403150322/http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/vikings-newfoundland-1.3515747|url-status=live}}</ref> Archaeologist Karen Milek was a member of the 2016 Point Rosee excavation and is a Norse expert. She also expressed doubt that Point Rosee was a Norse site as there are no good landing sites for their boats and there are steep cliffs between the shoreline and the excavation site.<ref name="CBC2016">{{cite news|last=Bird|first=Lindsay|date=12 September 2016|title=On the Trail of Vikings: Latest search for Norse in North America|publisher=CBC|url=http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/viking-dig-point-rosee-newfoundland-2016-1.3751129|access-date=12 March 2018|archive-date=31 May 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180531181120/http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/viking-dig-point-rosee-newfoundland-2016-1.3751129|url-status=live}}</ref> In their 8 November 2017 report,<ref name="SP2017">{{cite news|last1=Parcak|first1=Sarah|last2=Mumford|first2=Gregory|date=8 November 2017|title=Point Rosee, Codroy Valley, NL (ClBu-07) 2016 Test Excavations under Archaeological Investigation Permit #16.26|publisher=geraldpennyassociates.com, 42 pages|url=http://vocm.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/PENNEY-2017-Point-Rosee-Codroy-Valley-NL-Test-Excavation-Report.pdf|url-status=dead|access-date=19 June 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180620074156/http://vocm.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/PENNEY-2017-Point-Rosee-Codroy-Valley-NL-Test-Excavation-Report.pdf|archive-date=20 June 2018|quote= found no evidence whatsoever for either a Norse presence or human activity at Point Rosee prior to the historic period. ... None of the team members, including the Norse specialists, deemed this area as having any traces of human activity.}}</ref> ] and Gregory Mumford, co-directors of the excavation, wrote that they "found no evidence whatsoever for either a Norse presence or human activity at Point Rosee prior to the historic period"<ref name="TCP2018" /> and that "none of the team members, including the Norse specialists, deemed this area as having any traces of human activity."<ref name="CBC2018" /> | |||

| ==Duration of Norse contact== | |||

| Settlements in continental North America aimed to exploit natural resources such as furs and in particular lumber, which was in short supply in Greenland.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Diamond |first=Jared M. |author-link=Jared Diamond |title=Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed |title-link=Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed |date=2005 |publisher=Viking |isbn=978-0-670-03337-9 |location=New York}}</ref> It is unclear why the short-term settlements did not become permanent, though it was likely in part because of hostile relations with the indigenous peoples, referred to as the '']'' by the Norse.<ref>{{cite book |title=Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People, Compact |first1=John M |last1=Murrin |first2=Paul E |last2=Johnson |first3=James M |last3=McPherson |first4=Gary |last4=Gerstle |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4aNIeXqWz9YC&pg=PA6 |page=6 |publisher=Thomson Wadsworth |year=2008 |isbn=978-0-495-41101-7 |access-date=24 November 2010 |archive-date=2 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502034644/https://books.google.com/books?id=4aNIeXqWz9YC&pg=PA6 |url-status=live }}</ref> Nevertheless, it appears that sporadic voyages to Markland for forages, timber, and trade with the locals could have lasted as long as 400 years.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Schledermann |first=Peter |title=Voices in Stone: A Personal Journey into the Arctic Past |date=1996 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-919034-87-7 |series=Komatik series |location=Calgary}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Sutherland |first=Patricia |title=Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga |date=2000 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-56098-970-7 |editor-last=Fitzhugh |editor-first=William W. |location=Washington |chapter=The Norse and Native North Americans |editor-last2=Ward |editor-first2=Elisabeth I. |chapter-url=http://luna.cas.usf.edu/~rtykot/ant4149/Sutherland%202000.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| ] writes:<blockquote>From 985 to 1410, Greenland was in touch with the world. Then silence. In 1492 the ] noted that no news of that country "at the end of the world" had been received for 80 years, and the bishopric of the colony was offered to a certain ecclesiastic if he would go and "restore Christianity" there. He didn't go.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Curran|first=James Watson|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eSxCAAAAIAAJ|title=Here was Vinland: The Great Lakes Region of America|publisher=]|year=1939|location=Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario|pages=207|archive-date=2 May 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502034645/https://books.google.com/books?id=eSxCAAAAIAAJ|url-status=live}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * ] | |||

| *] - a feature film based on Vikings encountering Native Americans. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{commons category|Norse colonization of the Americas}} | |||

| * , Parks Canada website | |||

| * , Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage website | |||

| * at Dartmouth College Library | |||

| {{Canadian colonies}} | |||

| {{European Colonization of North America}} | |||

| {{Germanic peoples}} | |||

| {{Polar exploration|state=collapsed}} | |||

| {{Greenland topics}} | |||

| {{Pre-Columbian North America}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Norse Colonization Of The Americas}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 13:48, 5 January 2025

This article is about the Viking presence in the western Arctic. For the Swedish, see Swedish colonization of the Americas. For Danish-Norwegian, see Danish colonization of the Americas.

| Part of a series on the |

| Norse colonization of North America |

|---|

Leiv Eirikson Discovering America, 1893 painting by Christian Krohg Leiv Eirikson Discovering America, 1893 painting by Christian Krohg |

| Places |

| Alleged artifacts |

| Explorers |

| Literature |

| Researchers |

| Part of a series on |

| European colonization of the Americas |

|---|

|

|

|

The Norse exploration of North America began in the late 10th century, when Norsemen explored areas of the North Atlantic colonizing Greenland and creating a short term settlement near the northern tip of Newfoundland. This is known now as L'Anse aux Meadows where the remains of buildings were found in 1960 dating to approximately 1,000 years ago. This discovery helped reignite archaeological exploration for the Norse in the North Atlantic. This single settlement, located on the island of Newfoundland and not on the North American mainland, was abruptly abandoned.

The Norse settlements on Greenland lasted for almost 500 years. L'Anse aux Meadows, the only confirmed Norse site in present-day Canada, was small and did not last as long. Other such Norse voyages are likely to have occurred for some time, but there is no evidence of any Norse settlement on mainland North America lasting beyond the 11th century.

The Norse exploration of North America has been subject to numerous controversies concerning the European exploration and settlement of North America. Pseudoscientific and pseudohistorical theories have emerged since the public acknowledgment of these Norse expeditions and settlements.

Norse Greenland

Main article: Norse settlements in Greenland

According to the Sagas of Icelanders, Norsemen from Iceland first settled Greenland in the 980s. There is no special reason to doubt the authority of the information that the sagas supply regarding the very beginning of the settlement, but they cannot be treated as primary evidence for the history of Norse Greenland because they embody the literary preoccupations of writers and audiences in medieval Iceland that are not always reliable.

Erik the Red (Old Norse: Eiríkr rauði), having been banished from Iceland for manslaughter, explored the uninhabited southwestern coast of Greenland during the three years of his banishment. He made plans to entice settlers to the area, naming it Greenland on the assumption that "people would be more eager to go there because the land had a good name". The inner reaches of one long fjord, named Eiriksfjord after him, was where he eventually established his estate Brattahlíð. He issued tracts of land to his followers.

Norse Greenland consisted of two settlements. The Eastern was at the southwestern tip of Greenland, while the Western Settlement was about 500 km up the west coast, inland from present-day Nuuk. A smaller settlement near the Eastern Settlement is sometimes considered the Middle Settlement. The combined population was around 2,000–3,000. At least 400 farms have been identified by archaeologists. Norse Greenland had a bishopric (at Garðar) and exported walrus ivory, furs, rope, sheep, whale and seal blubber, live animals such as polar bears, supposed "unicorn horns" (in reality narwhal tusks), and cattle hides. In 1126, the population requested a bishop (headquartered at Garðar), and in 1261, they accepted the overlordship of the Norwegian king. They continued to have their own law and became almost completely politically independent after 1349, the time of the Black Death. In 1380, the Kingdom of Norway entered into a personal union with the Kingdom of Denmark.

Western trade and decline

There is evidence of Norse trade with the natives (called the Skrælingjar by the Norse). The Norse would have encountered both Native Americans (the Beothuk, related to the Algonquin) and the Thule, the ancestors of the Inuit. The Dorset had withdrawn from Greenland before the Norse settlement of the island. Items such as comb fragments, pieces of iron cooking utensils and chisels, chess pieces, ship rivets, carpenter's planes, and oaken ship fragments used in Inuit boats have been found far beyond the traditional range of Norse colonization. A small ivory statue that appears to represent a European has also been found among the ruins of an Inuit community house.