| Revision as of 09:05, 24 September 2008 view sourceJagged 85 (talk | contribs)87,237 edits updated influenced← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:46, 4 January 2025 view source HKLionel (talk | contribs)372 edits added link to entry in List of Genshin Impact characters | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Arab physicist, mathematician and astronomer (c. 965 – c. 1040)}} | |||

| <!--Beginning of the ]--> | |||

| {{redirect2|Alhazen|Alhaitham|other uses|Alhazen (disambiguation)|the fictional character|List of Genshin Impact characters#Alhaitham}} | |||

| {{Infobox_Muslim scholars | | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| <!-- Scroll down to edit this page --> | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2022}} | |||

| <!-- Philosopher Category --> | |||

| {{Infobox scientist | |||

| notability = ]| | |||

| | name = Alhazen<br />{{transliteration|ar|Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham}} | |||

| era = ]| | |||

| | native_name = {{lang|ar|ابن الهيثم}} | |||

| color = #cef2e0 | | |||

| | image = Hazan.png | |||

| | birth_date = {{nowrap |{{birth-date|0965|{{circa}} 965}} ({{c.|354 ]}})<ref name=Lorch>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Lorch |first=Richard |title=Ibn al-Haytham: Arab astronomer and mathematician |publisher=Encyclopedia Britannica |date=1 February 2017 |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ibn-al-Haytham |access-date=14 January 2022 |archive-date=12 August 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180812045403/https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ibn-al-Haytham |url-status=live }}</ref>}} | |||

| | birth_place = ], ] | |||

| | death_date = {{nowrap |{{death-date|1040|{{circa}} 1040}} ({{c.|430 AH}})<ref name=Lorch />}} (aged around 75) | |||

| | death_place = ], ] | |||

| | workplaces = | |||

| | field = ], ], ] | |||

| | alma_mater = | |||

| | notable_students = | |||

| | known_for = '']'', '']'', ], ],<ref>{{Harvnb|O'Connor|Robertson|1999}}.</ref> ],<ref>{{Harvnb|El-Bizri|2010|p=11}}: "Ibn al-Haytham's groundbreaking studies in optics, including his research in catoptrics and dioptrics (respectively the sciences investigating the principles and instruments pertaining to the reflection and refraction of light), were principally gathered in his monumental opus: Kitåb al-manåóir (The Optics; De Aspectibus or Perspectivae; composed between 1028 CE and 1038 CE)."</ref> ], ], ] of ], ], ], ]ology,<ref>{{Harvnb|Rooney|2012|p=39}}: "As a rigorous experimental physicist, he is sometimes credited with inventing the scientific method."</ref> ]<ref>{{Harvnb|Baker|2012|p=449}}: "As shown earlier, Ibn al-Haytham was among the first scholars to experiment with animal psychology.</ref> | |||

| | footnotes = | |||

| | Religion = | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham''' (] as '''Alhazen'''; {{IPAc-en|æ|l|ˈ|h|æ|z|ən}}; full name {{transliteration|ar|ALA|Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥasan ibn al-Ḥasan ibn al-Haytham}} {{lang|ar|أبو علي، الحسن بن الحسن بن الهيثم}}; {{c.|lk=no|965|1040}}) was a medieval ], ], and ] of the ] from present-day Iraq.<ref>Also ''Alhacen'', ''Avennathan'', ''Avenetan'', etc.; the identity of "Alhazen" with Ibn al-Haytham al-Basri "was identified towards the end of the 19th century". ({{harvnb|Vernet|1996|p=788}})</ref><ref>{{Cite American Heritage Dictionary|Ibn al-Haytham|access-date=23 June 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Esposito|first1=John L.|title=The Oxford History of Islam|date=2000|publisher=Oxford University Press|page=192}}: "Ibn al-Haytham (d. 1039), known in the West as Alhazan, was a leading Arab mathematician, astronomer, and physicist. His optical compendium, Kitab al-Manazir, is the greatest medieval work on optics."</ref><ref name="Vernet 1996 788">For the description of his main fields, see e.g. {{harvnb|Vernet|1996|p=788}} ("He is one of the principal Arab mathematicians and, without any doubt, the best physicist.") {{Harvnb|Sabra|2008}}, {{Harvnb|Kalin|Ayduz|Dagli|2009|p=}} ("Ibn al-Ḥaytam was an eminent eleventh-century Arab optician, geometer, arithmetician, algebraist, astronomer, and engineer."), {{Harvnb|Dallal|1999|p=}} ("Ibn al-Haytham (d. 1039), known in the West as Alhazan, was a leading Arab mathematician, astronomer, and physicist. His optical compendium, Kitab al-Manazir, is the greatest medieval work on optics.")</ref> Referred to as "the father of modern optics",<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Masic |first=Izet |date=2008 |title=Ibn al-Haitham--father of optics and describer of vision theory. |journal=Medicinski Arhiv |volume=62 |issue=3 |pages=183–188 |pmid=18822953 |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/23286650}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://en.unesco.org/news/international-year-light-ibn-al-haytham-pioneer-modern-optics-celebrated-unesco|title=International Year of Light: Ibn al Haytham, pioneer of modern optics celebrated at UNESCO|website=UNESCO|language=en|access-date=2 June 2018|archive-date=18 September 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150918044445/https://en.unesco.org/news/international-year-light-ibn-al-haytham-pioneer-modern-optics-celebrated-unesco|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Khalili">{{Cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7810846.stm|work=BBC News|title=The 'first true scientist'|author=Al-Khalili, Jim|date=4 January 2009|access-date=2 June 2018|archive-date=26 April 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150426041228/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7810846.stm|url-status=live}}</ref> he made significant contributions to the principles of ] and ] in particular. His most influential work is titled '']'' (]: {{lang|ar|كتاب المناظر}}, "Book of Optics"), written during 1011–1021, which survived in a Latin edition.<ref>{{Harvnb|Selin|2008|p=}}: "The three most recognizable Islamic contributors to meteorology were: the Alexandrian mathematician/ astronomer Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen 965–1039), the Arab-speaking Persian physician Ibn Sina (Avicenna 980–1037), and the Spanish Moorish physician/jurist Ibn Rushd (Averroes; 1126–1198)." He has been dubbed the "father of modern optics" by the ]. {{Cite journal|date=1976|title=Impact of Science on Society|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4YE3AAAAMAAJ|journal=UNESCO|volume=26–27|page=140|access-date=12 September 2019|archive-date=5 February 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230205005719/https://books.google.com/books?id=4YE3AAAAMAAJ|url-status=live}}. | |||

| {{Cite web|url=http://www.light2015.org/Home/ScienceStories/1000-Years-of-Arabic-Optics.html|title=International Year of Light – Ibn Al-Haytham and the Legacy of Arabic Optics|website=www.light2015.org|language=en|access-date=9 October 2017|archive-date=1 October 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141001171116/http://www.light2015.org/Home/ScienceStories/1000-Years-of-Arabic-Optics.html|url-status=dead}}. | |||

| {{Cite web|url=https://en.unesco.org/news/international-year-light-ibn-al-haytham-pioneer-modern-optics-celebrated-unesco|title=International Year of Light: Ibn al Haytham, pioneer of modern optics celebrated at UNESCO|website=UNESCO|language=en|access-date=9 October 2017|archive-date=18 September 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150918044445/https://en.unesco.org/news/international-year-light-ibn-al-haytham-pioneer-modern-optics-celebrated-unesco|url-status=live}}. Specifically, he was the first to explain that vision occurs when light bounces on an object and then enters an eye. {{cite book|last=Adamson|first=Peter|title=Philosophy in the Islamic World: A History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KEpRDAAAQBAJ|date=2016|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-957749-1|page=77|access-date=3 October 2016|archive-date=5 February 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230205005719/https://books.google.com/books?id=KEpRDAAAQBAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> The works of Alhazen were frequently cited during the scientific revolution by ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| Ibn al-Haytham was the first to correctly explain the theory of vision,<ref name="Adamson 2016 77">{{cite book|last=Adamson|first=Peter|title=Philosophy in the Islamic World: A History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KEpRDAAAQBAJ|year=2016|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-957749-1|page=77|access-date=3 October 2016|archive-date=5 February 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230205005719/https://books.google.com/books?id=KEpRDAAAQBAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> and to argue that vision occurs in the brain, pointing to observations that it is subjective and affected by personal experience.{{sfn|Baker|2012|p=445}} He also stated the principle of least time for refraction which would later become ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Rashed |first=Roshdi |date=2019-04-01 |title=Fermat et le principe du moindre temps |journal= Comptes Rendus Mécanique |volume=347 |issue=4 |pages=357–364 |doi=10.1016/j.crme.2019.03.010 |bibcode=2019CRMec.347..357R |s2cid=145904123 |issn=1631-0721|doi-access=free }}</ref> He made major contributions to catoptrics and dioptrics by studying reflection, refraction and nature of images formed by light rays.{{sfn|Selin|2008|p=1817}}<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Boudrioua |first1=Azzedine |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6_0wDwAAQBAJ&dq=Law+of+reflection+ibn+al+haitham&pg=PT29 |title=Light-Based Science: Technology and Sustainable Development, The Legacy of Ibn al-Haytham |last2=Rashed |first2=Roshdi |last3=Lakshminarayanan |first3=Vasudevan |year=2017 |publisher=CRC Press |isbn=978-1-351-65112-7 |language=en |access-date=22 February 2023 |archive-date=6 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230306044312/https://books.google.com/books?id=6_0wDwAAQBAJ&dq=Law+of+reflection+ibn+al+haitham&pg=PT29 |url-status=live }}</ref> Ibn al-Haytham was an early proponent of the concept that a hypothesis must be supported by experiments based on confirmable procedures or mathematical reasoning{{snd}}an early pioneer in the ] five centuries before ],<ref>] (2009). "Science in Islam". Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages. {{ISSN|1703-7603}}. Retrieved 22 October 2014.</ref><ref>]. {{jstor|1=228328?pg=464}}, Toomer's 1964 review of Matthias Schramm (1963) ''Ibn Al-Haythams Weg Zur Physik''] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170326070235/http://www.jstor.org/stable/228328?pg=464 |date=26 March 2017 }} Toomer p. 464: "Schramm sums up achievement in the development of scientific method."</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.light2015.org/Home/ScienceStories/1000-Years-of-Arabic-Optics.html|title=International Year of Light – Ibn Al-Haytham and the Legacy of Arabic Optics|access-date=4 January 2015|archive-date=1 October 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141001171116/http://www.light2015.org/Home/ScienceStories/1000-Years-of-Arabic-Optics.html|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Gorini|first=Rosanna|title=Al-Haytham the man of experience. First steps in the science of vision|url=http://www.ishim.net/ishimj/4/10.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.ishim.net/ishimj/4/10.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live|journal=Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine|volume=2|issue=4|pages=53–55|date=October 2003|access-date=25 September 2008}}</ref> he is sometimes described as the world's "first true scientist".<ref name=Khalili /> He was also a ], writing on ], ] and ].<ref>], ''Ibn al-Haytham's Geometrical Methods and the Philosophy of Mathematics: A History of Arabic Sciences and Mathematics, Volume 5'', Routledge (2017), p. 635</ref> | |||

| <!-- Images --> | |||

| image_name = Ibn al-Haytham.png| | |||

| image_caption = Ibn al-Haytham drawing taken from a 1982 Iraqi 10-dinar note. | | |||

| signature = | | |||

| Born in ], he spent most of his productive period in the ] capital of ] and earned his living authoring various treatises and tutoring members of the nobilities.<ref>According to ]. {{Harvnb|O'Connor|Robertson|1999}}.</ref> Ibn al-Haytham is sometimes given the ] ''al-Baṣrī'' after his birthplace,<ref>{{harvnb|O'Connor|Robertson|1999}}</ref> or ''al-Miṣrī'' ("the Egyptian").<ref>{{harvnb|O'Connor|Robertson|1999|p=}}</ref><ref>Disputed: {{harvnb|Corbin|1993|p=149}}.</ref> Al-Haytham was dubbed the "Second ]" by ]<ref name=bayhaqi>Noted by ] (c. 1097–1169), and by | |||

| <!-- Information --> | |||

| * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230205005728/https://books.google.com/books?id=AsnaAAAAMAAJ |date=5 February 2023 }} p. 197 | |||

| name = '''{{Unicode|Abū ‘Alī al-Ḥasan ibn al-Ḥasan ibn al-Haytham}}'''| | |||

| * </ref> and "The Physicist" by ].<ref>{{harvnb|Lindberg|1967|p=331}}:"Peckham continually bows to the authority of Alhazen, whom he cites as "the Author" or "the Physicist"."</ref> Ibn al-Haytham paved the way for the modern science of physical optics.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mhLVHR5QAQkC|title=Ptolemy's Theory of Visual Perception: An English Translation of the Optics|last=A. Mark Smith|publisher=American Philosophical Society|year=1996|isbn=978-0-87169-862-9|page=57|access-date=16 August 2019|archive-date=5 February 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230205005720/https://books.google.com/books?id=mhLVHR5QAQkC|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| title= '''Ibn al-Haytham''' and '''Alhacen'''| | |||

| birth = 965<ref name=Britannica/> | | |||

| death = c. 1040<ref name=Britannica/> | | |||

| Ethnicity = ] and/or ] | | |||

| Region = ] (]) and ] | | |||

| main_interests = ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | | |||

| notable idea = Pioneer in ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], non-], ] | | |||

| influences = ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | | |||

| influenced = ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | | |||

| works = '']'', ''Doubts Concerning Ptolemy'', ''On the Configuration of the World'', ''The Model of the Motions'', ''Treatise on Light'', ''Treatise on Place'' | | |||

| }} | |||

| <!--End of the template--> | |||

| {{dablink|This article is about the scientist. For the crater on the Moon named after him, see ]. For the asteroid, see ].}} | |||

| {{SpecialCharsNote}} | |||

| '''{{transl|ar|ALA|Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥasan ibn al-Ḥasan ibn al-Haytham}}''' (]: ابو علی، حسن بن حسن بن هيثم, ]: '''Alhacen''' or (deprecated) '''Alhazen''') (965–c. 1039), was an ]<ref>{{Harv|Smith|1992}} <br> {{Harv|Grant|2008}} <br> {{Harv|Vernet|2008}} <br> {{citation|url=http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1E1-IbnalHay.html|contribution=Ibn al-Haytham|title=]|edition=Sixth|year=2007|accessdate=2008-01-23}}</ref> and/or ]<ref>{{Harv|Child|Shuter|Taylor|1992|p=70}} <br> {{Harv|Dessel|Nehrich|Voran|1973|p=164}} <br> {{Harv|Samuelson|Crookes|p=497}}</ref> ].<ref>{{Harv|Hamarneh|1972}}: {{quote|A great man and a universal genius, long neglected even by his own people.}} {{Harv|Bettany|1995}}: {{quote|Ibn ai-Haytham provides us with the historical personage of a versatile universal genius.}}</ref> He made significant contributions to the principles of ], as well as to ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and to ] in general with his introduction of the ]. He is sometimes called '''al-Basri''' (Arabic: البصري), after his birthplace in the city of ].<ref name=MacTutor/> He was also nicknamed ''Ptolemaeus Secundus'' ("] the Second")<ref name="Corbin149">{{Harv|Corbin|1993|p=149}}</ref> or simply "The Physicist"<ref>{{Harv|Lindberg|1967|p=331}}</ref> in medieval Europe. | |||

| == Biography == | |||

| Though born in what is now modern-day ] around the year 965<ref name=Britannica>{{Harv|Lorch|2008}}</ref>, he spent most of his life in ], ], dying there at the age of 76.<ref name="Corbin149"/> In his over-confidence about the practical application of his mathematical knowledge, he assumed that he could regulate the floods caused by the overflow of the ].<ref name=Sabra>{{Harv|Sabra|2003}}</ref> After being ordered by ], the sixth ruler of the Arab caliphate, to carry out this operation, he quickly perceived the inanity of what he was attempting to do, and retired from engineering. Fearing for his life, he ]<ref name=Britannica/><ref name=Encarta>{{Harv|Grant|2008}}</ref> and was placed under ], during and after which he devoted himself to his scientific work until his death.<ref name="Corbin149"/> | |||

| Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) was born c. 965 to a family of ]<ref name="Vernet 1996 788" /><ref name="Simon 2006">{{harvnb|Simon|2006}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Gregory |first=Richard Langton |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FpMYAAAAIAAJ |title=The Oxford Companion to the Mind |date=2004 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-866224-2 |page=24 |language=en |access-date=28 June 2023 |archive-date=4 December 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231204161231/https://books.google.com/books?id=FpMYAAAAIAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref> | |||

| Ibn al-Haytham is regarded as the "father of modern optics"<ref>{{Harv|Verma|1969}}</ref> for his influential '']'' (written while he was under house arrest), which correctly explained and proved the modern intromission theory of vision. He is also recognized so for his ]s on optics, including experiments on ], ]s, ], ], and the dispersion of ] into its constituent colours.<ref name=Deek/> | |||

| "Alhazen Arab mathematician and physicist who was born around 965 in what is now Iraq." Critical Companion to Chaucer: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work | |||

| He studied ] and the ], described the ]<ref>{{Harv|MacKay|Oldford|2000}}</ref><ref name=Hamarneh/> of light, and argued that it is made of ]<ref>{{Harv|Rashed|2007|p=19}}: {{quote|"In his optics ‘‘the smallest parts of light’’, as he calls them, retain only properties that can be treated by geometry and verified by experiment; they lack all sensible qualities except energy."}}</ref> travelling in straight lines.<ref name=Hamarneh>{{Harv|Hamarneh|1972|p=119}}</ref><ref>{{Harv|O'Connor|Robertson|2002}}</ref> | |||

| </ref><ref>Esposito (2000)، The Oxford History of Islam، Oxford University Press، p. 192. : "Ibn al-Haytham (d. 1039), known in the West as Alhazan, was a leading Arab mathematician, astronomer, and physicist. His optical compendium, Kitab al-Manazir, is the greatest medieval work on optics"</ref> or ]<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mk_CBAAAQBAJ&dq=alhazen+History+and+Evolution+of+Concepts+in+Physics&pg=PA23 |title=History and Evolution of Concepts in Physics |page =24 |isbn=978-3-319-04292-3 |access-date=13 March 2023 |archive-date=20 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230620164804/https://books.google.com/books?id=mk_CBAAAQBAJ&dq=alhazen+History+and+Evolution+of+Concepts+in+Physics&pg=PA23 |url-status=live |last1=Varvoglis |first1=Harry |date=29 January 2014 |publisher=Springer }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3nBJAAAAYAAJ&dq=alhazen&pg=PA59 |title=Chemical News and Journal of Industrial Science|volume =34 |page =59 |date=6 January 1876 |access-date=13 March 2023 |archive-date=26 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230326164818/https://books.google.com/books?id=3nBJAAAAYAAJ&dq=alhazen&pg=PA59 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_NDOCwAAQBAJ&dq=Renaissance++John+Shannon+Hendrix,+Charles+eleventh+century&pg=PA77 |title=Renaissance Theories of Vision edited by John Shannon Hendrix, Charles |page =77 |isbn=978-1-317-06640-8 |access-date=13 March 2023 |archive-date=20 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230620164804/https://books.google.com/books?id=_NDOCwAAQBAJ&dq=Renaissance++John+Shannon+Hendrix,+Charles+eleventh+century&pg=PA77 |url-status=live |last1=Hendrix |first1=John Shannon |last2=Carman |first2=Charles H. |date=5 December 2016 |publisher=Routledge }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZQfcDwAAQBAJ&dq=Quantum+Mechanics+for+Beginners+alhazen&pg=PA81 |title=Quantum Mechanics for Beginners: With Applications to Quantum Communication By M. Suhail Zubairy |page =81 |isbn=978-0-19-885422-7 |access-date=13 March 2023 |archive-date=20 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230620164806/https://books.google.com/books?id=ZQfcDwAAQBAJ&dq=Quantum+Mechanics+for+Beginners+alhazen&pg=PA81 |url-status=live |last1=Suhail Zubairy |first1=M. |date=6 January 2024 |publisher=Oxford University Press }}</ref><ref>{{Harvard citation|Child|Shuter|Taylor|1992|p=70}}, {{Harvard citation|Dessel|Nehrich|Voran|1973|p=164}}, ''Understanding History'' by John Child, Paul Shuter, David Taylor, p. 70. "Alhazen, a Persian scientist, showed that the eye saw light from other objects. This started optics, the science of light. The Arabs also studied astronomy, the study of the stars. "</ref> origin in ], ], which was at the time part of the ]. His initial influences were in the study of religion and service to the community. At the time, society had a number of conflicting views of religion that he ultimately sought to step aside from religion. This led to him delving into the study of mathematics and science.<ref name=Tbakhi>{{Cite journal|last1=Tbakhi|first1=Abdelghani|last2=Amr|first2=Samir S.|date=2007|title=Ibn Al-Haytham: Father of Modern Optics|journal=Annals of Saudi Medicine|volume=27|issue=6|pages=464–467|doi=10.5144/0256-4947.2007.464|issn=0256-4947|pmc=6074172|pmid=18059131}}</ref> He held a position with the title of ] in his native Basra, and became famous for his knowledge of applied mathematics, as evidenced by his attempt to regulate the ].<ref name="Corbin 1993 149">{{Harvnb|Corbin|1993|p=149}}.</ref> | |||

| Due to his formulation of a modern ] and ] approach to ] and science, he is considered the pioneer of the modern scientific method<ref name=Gorini/><ref name=Agar>{{Harv|Agar|2001}}</ref> and the originator of the ]<ref>{{Harv|Thiele|2005}}</ref> and science<ref>{{Harv|Omar|1977}}</ref> Author Bradley Steffens describes him as the "first scientist".<ref>{{Harv|Steffens|2006}}</ref> | |||

| He is also considered by ] to be the founder of ]<ref name=Khaleefa>{{Harv|Khaleefa|1999}}</ref> for his approach to visual perception and ]s,<ref name=Steffens>{{Harv|Steffens|2006}}, Chapter 5</ref> and a pioneer of the philosophical field of ] or the study of ] from a ]. | |||

| His ''Book of Optics'' has been ranked with ]'s '']'' as one of the most influential books in the ],<ref name=Salih>{{Harv|Salih|Al-Amri|El Gomati|2005}}</ref> for starting a ] in optics<ref name=Hogendijk/> and visual perception.<ref name=Ragep/> | |||

| Upon his return to Cairo, he was given an administrative post. After he proved unable to fulfill this task as well, he contracted the ire of the caliph ],<ref>The Prisoner of Al-Hakim. Clifton, NJ: Blue Dome Press, 2017. {{ISBN|1682060160}}</ref> and is said to have been forced into hiding until the caliph's death in 1021, after which his confiscated possessions were returned to him.<ref>], ''Geschichte der arabischen Litteratur'', vol. 1 (1898), .</ref> | |||

| Ibn al-Haytham's achievements include many advances in physics and mathematics. He gave the first clear description<ref name=Kelley/> and correct analysis<ref name=Wade/> of the ]. He enunciated ] of least time and the concept of ] (]),<ref name=Salam/> and developed the concept of ].<ref name=Nasr/> He described the ] between ]es and was aware of the ] of ] due to gravity ].<ref name=Bizri>{{Harv|El-Bizri|2006}}</ref> He stated that the ] were accountable to the ] and also presented a critique and reform of ]. He was the first to state ] in ], and he formulated the ]<ref name=Rozenfeld/> and a concept similar to ]<ref name=Smith>{{Harv|Smith|1992}}</ref> now used in ]. Moreover, he formulated and solved ] geometrically using early ideas related to ] and ].<ref name=Katz/> In his optical research, he laid the foundations for the later development of ] astronomy,<ref name=Marshall>{{Harv|Marshall|1950}}</ref> as well as for the ] and the use of optical aids in ] art.<ref name=Power/> | |||

| Legend has it that Alhazen ] and was kept under house arrest during this period.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cgie.org.ir/shavad.asp?id=123&avaid=1917 |title=the Great Islamic Encyclopedia |publisher=Cgie.org.ir |access-date=27 May 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110930153427/http://www.cgie.org.ir/shavad.asp?id=123&avaid=1917 |archive-date=30 September 2011 }}{{verify source|date=February 2016}}</ref> During this time, he wrote his influential '']''. Alhazen continued to live in Cairo, in the neighborhood of the famous ], and lived from the proceeds of his literary production<ref>For Ibn al-Haytham's life and works, {{harvnb|Smith|2001|p=cxix}} recommends {{harvnb|Sabra|1989|pp=vol. 2, xix–lxxiii}}</ref> until his death in c. 1040.<ref name="Corbin 1993 149" /> (A copy of ]' ''Conics'', written in Ibn al-Haytham's own handwriting exists in ]: (MS Aya Sofya 2762, 307 fob., dated Safar 415 A.H. ).)<ref>{{cite web| url = https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/ibn-al-haytham-abu| title = A. I. Sabra encyclopedia.com Ibn Al-Haytham, Abū| access-date = 4 November 2018| archive-date = 26 March 2023| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230326025108/https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/ibn-al-haytham-abu| url-status = live}}</ref>{{rp|Note 2}} | |||

| Among his students were Sorkhab (Sohrab), a Persian from ], and ], an Egyptian prince.<ref>Sajjadi, Sadegh, "Alhazen", ''Great Islamic Encyclopedia'', Volume 1, Article No. 1917</ref>{{verify source|date=February 2016}} | |||

| ==Overview== | |||

| ===Biography=== | |||

| Abū ‘Alī al-Hasan ibn al-Hasan ibn al-Haytham (and known in Europe as Alhacen or Alhazen) was born in ], then under the rule of the ] of the ] and now part of ],<ref name=MacTutor/> and he probably died in ], ]. During the ], Basra was a "key centre of learning",<ref name=Guardian>{{Harv|Whitaker|2004}}</ref> and he was educated there and in ], the capital of the ], and the focus of the "high point of Islamic civilisation".<ref name=Guardian/> During his time in Iraq, he worked as a ] and read many ] and ] books.<ref name=MacTutor>{{Harv|O'Connor|Robertson|1999}}</ref> | |||

| == ''Book of Optics'' == | |||

| One account of his career has him summoned to Egypt by the ] ], ruler of the ], to regulate the ], a task requiring an early attempt at building a ] at the present site of the ].<ref>{{Harv|Rashed|2002b}}</ref> After his ] made him aware of the impracticality of this scheme,<ref name="Corbin149"/> and fearing the caliph's anger, he ]. He was kept under ] from 1011 until al-Hakim's death in 1021.<ref>"به گفتۀ قفطی... ابن هیثم اندکی بعد در رأس گروهی از مهندسان به بررسی نیل و مجرای آن در بخش مرتفع جنوب مصر پرداخت، اما با مشاهدۀ آثار و ابنیهای که مصریان براساس طرحهای دقیق هندسی ساخته بودند، دریافت که اگر اجرای طرحی که او در اندیشه داشت، ممکن بود، این مصریان فرهیختۀ دانا به هندسه و ریاضیات، البته پیشتر به آن دست میزدند. | |||

| {{Main|Book of Optics}} | |||

| بررسی چگونگی مرتفعات اسوان که نیل از آن میگذرد، نیز این نتیجهگیری را تأیید کرد. از اینرو نزد خلیفه به ناکامی خود اعتراف کرد. ظاهراً خلیفه واکنش تندی از خود نشان نداد، اما چنین مینماید که از این ناکامی چندان خشمناک شده بود که ابن هیثم را به جای آنکه در جایی چون دارالحکمۀ قاهره، در کنار کسانی مانند ابن یونس منجم به کار بگمارد، به شغلی دیوانی گماشت. ابن هیثم با آنکه از بیم این فرمانروای خونریز، به این شغل گردن نهاد، ولی برای رهایی از آن چاره در این دید که باز تظاهر به جنون کند. از اینرو خلیفه اموال او را مصادره کرد و کسی را به قیمومتش گماشت و در خانهاش محبوس کرد. چون الحاکم درگذشت (411ق/1020م)، ابن هیثم نیز از تظاهر به جنون دست برداشت و آزاد شد و اموالش را باز پس گرفت. " </ref> During this time, he wrote his influential '']''. | |||

| Alhazen's most famous work is his seven-volume treatise on ] ''Kitab al-Manazir'' (''Book of Optics''), written from 1011 to 1021.<ref>{{Harvnb|Al-Khalili|2015}}.</ref> In it, Ibn al-Haytham was the first to explain that vision occurs when light reflects from an object and then passes to one's eyes,<ref name="Adamson 2016 77"/> and to argue that vision occurs in the brain, pointing to observations that it is subjective and affected by personal experience.{{sfn|Baker|2012|p=445}} | |||

| Although there are stories that Ibn al-Haytham fled to Syria, ventured into Baghdad later in his life, or was even in Basra when he pretended to be insane, it is certain that he was in Egypt by 1038 at the latest.<ref name=MacTutor/> During his time in Cairo, he became associated with ], as well the city's "House of Wisdom",<ref>{{Harv|Van Sertima|1992|p=382}}</ref> known as ''Dar Al-Hekma'' (]), which was a library "second in importance" to Baghdad's ].<ref name=MacTutor/> After his house arrest ended, he wrote scores of other treatises on ], ] and ]. He later traveled to ]. During this period, he had ample time for his scientific pursuits, which included optics, mathematics, physics, ], and the development of scientific methods; he left several outstanding books on these subjects. | |||

| ''Optics'' was ] by an unknown scholar at the end of the 12th century or the beginning of the 13th century.<ref>{{harvnb|Crombie|1971|p=147, n. 2}}.</ref>{{ efn| A. Mark Smith has determined that there were at least two translators, based on their facility with Arabic; the first, more experienced scholar began the translation at the beginning of Book One, and handed it off in the middle of Chapter Three of Book Three. {{harvnb|Smith|2001}} '''91''' Volume 1: Commentary and Latin text pp.xx–xxi. See also his 2006, 2008, 2010 translations.}} | |||

| ===Legacy=== | |||

| Ibn al-Haythem made significant improvements in optics, physical science, and the scientific method which influenced the development of science for over five hundred years after his death. Ibn al-Haytham's work on optics is credited with contributing a new emphasis on experiment. His influence on ]s in general, and on optics in particular, has been held in high esteem and, in fact, ushered in a new era in optical research, both in theory and practice.<ref name=Deek/> The scientific method is considered to be so fundamental to ] that some—especially ] and practising scientists—consider earlier inquiries into nature to be ''pre-scientific''.<ref>{{Harv|Briffault|1928|p=190–202}}: | |||

| {{quote|What we call science arose as a result of new methods of experiment, observation, and measurement, which were introduced into Europe by the Arabs. Science is the most momentous contribution of Arab civilization to the modern world, but its fruits were slow in ripening. Not until long after Moorish culture had sunk back into darkness did the giant to which it had given birth, rise in his might. It was not science only which brought Europe back to life. Other and manifold influences from the civilization of Islam communicated its first glow to European life. The debt of our science to that of the Arabs does not consist in startling discoveries or revolutionary theories; science owes a great deal more to Arab culture, it owes its existence…The ancient world was, as we saw, pre-scientific. The astronomy and mathematics of Greeks were a foreign importation never thoroughly acclimatized in Greek culture. The Greeks systematized, generalized and theorized, but the patient ways of investigations, the accumulation of positive knowledge, the minute methods of science, detailed and prolonged observation and experimental inquiry were altogether alien to the Greek temperament. What we call science arose in Europe as a result of new spirit of enquiry, of new methods of experiment, observation, measurement, of the development of mathematics, in a form unknown to the Greeks. That spirit and those methods were introduced into the European world by the Arabs.}}</ref> | |||

| This work enjoyed a great reputation during the ]. The Latin version of ''De aspectibus'' was translated at the end of the 14th century into Italian vernacular, under the title ''De li aspecti''.<ref>{{Cite journal |author=] | title=Nota intorno ad una traduzione italiana fatta nel secolo decimoquarto del trattato d'ottica d'Alhazen |journal=Bollettino di Bibliografia e di Storia delle Scienze Matematiche e Fisiche | year=1871 | volume=4 |pages=1–40}}. On this version, see {{harvnb|Raynaud|2020|pp=139–153}}.</ref> | |||

| ] nominated Ibn al-Haytham's scientific method and ] as the most influential idea of the ].<ref name=Power>{{Harv|Powers|1999}}</ref> Recipient of the ] ] considered Ibn-al-Haytham "one of the greatest physicists of all time."<ref name=Salam>{{Harv|Salam|1984}}: | |||

| {{quote|Ibn-al-Haitham (Alhazen, 965–1039 CE) was one of the greatest physicists of all time. He made experimental contributions of the highest order in optics. He enunciated that a ray of light, in passing through a medium, takes the path which is the easier and 'quicker'. In this he was anticipating Fermat's Principle of Least Time by many centuries. He enunciated the law of inertia, later to become Newton's first law of motion. Part V of Roger Bacon's "''Opus Majus''" is practically an annotation to Ibn al Haitham's ''Optics''.}}</ref> | |||

| ], the father of the ], wrote that "Ibn Haytham's writings reveal his fine development of the experimental faculty" and considered him "not only the greatest Muslim physicist, but by all means the greatest of mediaeval times."<ref>{{Harv|Sarton|1927}}, "The Time of Al-Biruni": | |||

| {{quote| was not only the greatest Muslim physicist, but by all means the greatest of mediaeval times.}} | |||

| {{quote|Ibn Haytham's writings reveal his fine development of the experimental faculty. His tables of corresponding angles of incidence and refraction of light passing from one medium to another show how closely he had approached discovering the law of constancy of ratio of sines, later attributed to Snell. He accounted correctly for twilight as due to atmospheric refraction, estimating the sun's depression to be 19 degrees below the horizon, at the commencement of the phenomenon in the mornings or at its termination in the evenings.}} (] {{Harv|Dr. Zahoor|Dr. Haq|1997}})</ref> Robert S. Elliot considers Ibn al-Haytham to be "one of the ablest students of optics of all times."<ref>{{Harv|Elliott|1966}}, Chapter 1: | |||

| {{quote|Alhazen was one of the ablest students of optics of all times and published a seven-volume treatise on this subject which had great celebrity throughout the medieval period and strongly influenced Western thought, notably that of Roger Bacon and Kepler. This treatise discussed concave and convex mirrors in both cylindrical and spherical geometries, anticipated Fermat's law of least time, and considered refraction and the magnifying power of lenses. It contained a remarkably lucid description of the optical system of the eye, which study led Alhazen to the belief that light consists of rays which originate in the object seen, and not in the eye, a view contrary to that of Euclid and Ptolemy.}}</ref> The author Bradley Steffens considers him to be the "first scientist".<ref>{{Harv|Steffens|2006}}</ref> The ''Biographical Dictionary of Scientists'' wrote that Ibn al-Haytham was "probably the greatest scientist of the Middle Ages" and that "his work remained unsurpassed for nearly 600 years until the time of Johannes Kepler."<ref>"Alhazen", in {{Harv|Abbott|1983|p=75}}: | |||

| {{quote|He was probably the greatest scientist of the Middle Ages and his work remained unsurpassed for nearly 600 years until the time of Johannes Kepler.}}</ref> At a scientific conference in February 2007 as a part of the ], ] argued that Ibn al-Haytham's work on optics may have influenced the use of optical aids by ] ]ists. Falco said that his and ]'s examples of Renaissance art "demonstrate a continuum in the use of optics by artists from ''circa'' 1430, arguably initiated as a result of Ibn al-Haytham's influence, until today."<ref>{{Harv|Falco|2007}}</ref> | |||

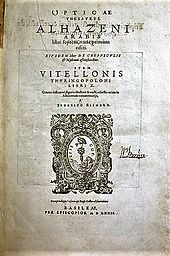

| It was printed by ] in 1572, with the title ''Opticae thesaurus: Alhazeni Arabis libri septem, nuncprimum editi; Eiusdem liber De Crepusculis et nubium ascensionibus'' (English: Treasury of Optics: seven books by the Arab Alhazen, first edition; by the same, on twilight and the height of clouds).<ref>{{Citation|url=http://www.mala.bc.ca/~mcneil/cit/citlcalhazen1.htm |title=Alhazen (965–1040): Library of Congress Citations | publisher=Malaspina Great Books |access-date=23 January 2008 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927190009/http://www.mala.bc.ca/~mcneil/cit/citlcalhazen1.htm |archive-date=27 September 2007 }}{{verify source|date=February 2016}}</ref> | |||

| The ] of his main work, ''Kitab al-Manazir'' (''Book of Optics''), exerted a great influence on Western science: for example, on the work of ], who cites him by name,<ref>{{Harv|Lindberg|1996|p=11}}, passim</ref> and on ]. It brought about a great progress in experimental methods. His research in ] (the study of optical systems using mirrors) centred on spherical and ] mirrors and ]. He made the observation that the ratio between the ] and ] does not remain constant, and investigated the ] power of a ]. His work on catoptrics also contains the problem known as "Alhazen's problem".<ref name=Deek/> | |||

| Risner is also the author of the name variant "Alhazen"; before Risner he was known in the west as Alhacen.<ref>{{harvnb|Smith|2001|p=xxi}}.</ref> | |||

| Works by Alhazen on geometric subjects were discovered in the ] in ] in 1834 by E. A. Sedillot. In all, A. Mark Smith has accounted for 18 full or near-complete manuscripts, and five fragments, which are preserved in 14 locations, including one in the ] at ], and one in the library of ].<ref>{{harvnb|Smith|2001|p=xxii}}.</ref> | |||

| === Theory of optics === | |||

| Meanwhile in the Islamic world, Ibn al-Haytham's work influenced ]' writings on optics,<ref name=Topdemir-77> | |||

| {{See also|Horopter}} | |||

| {{Harv|Topdemir|2007a|p=77}}</ref> and his legacy was further advanced through the 'reforming' of his ''Optics'' by Persian scientist ] (d. ca. 1320) in the latter's ''Kitab Tanqih al-Manazir'' (''The Revision of'' ''Optics'').<ref name=Steffens/><ref name=Bizri-2005/> The correct explanations of the rainbow phenomenon given by al-Fārisī and ] in the 14th Century depended on Ibn al-Haytham's ''Book of Optics''.<ref>{{Harv|Topdemir|2007a|p=83}}</ref> The work of Ibn al-Haytham and al-Fārisī was also further advanced in the ] by polymath ] in his ''Book of the Light of the Pupil of Vision and the Light of the Truth of the Sights'' (1574).<ref>{{Harv|Topdemir|1999}} (] {{Harv|Topdemir|2008}})</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Two major theories on vision prevailed in ]. The first theory, the ], was supported by such thinkers as ] and ], who believed that sight worked by the ] emitting ] of ]. The second theory, the ] supported by ] and his followers, had physical forms entering the eye from an object. Previous Islamic writers (such as ]) had argued essentially on Euclidean, Galenist, or Aristotelian lines. The strongest influence on the ''Book of Optics'' was from Ptolemy's ], while the description of the anatomy and physiology of the eye was based on Galen's account.<ref>{{harvnb|Smith|2001|p=lxxix}}.</ref> Alhazen's achievement was to come up with a theory that successfully combined parts of the mathematical ray arguments of Euclid, the medical tradition of ], and the intromission theories of Aristotle. Alhazen's intromission theory followed al-Kindi (and broke with Aristotle) in asserting that "from each point of every colored body, illuminated by any light, issue light and color along every straight line that can be drawn from that point".<ref name="{{harvnb|lindberg|1976|p=73}}.">{{harvnb|Lindberg|1976|p=73}}.</ref> This left him with the problem of explaining how a coherent image was formed from many independent sources of radiation; in particular, every point of an object would send rays to every point on the eye. | |||

| What Alhazen needed was for each point on an object to correspond to one point only on the eye.<ref name="{{harvnb|lindberg|1976|p=73}}." /> He attempted to resolve this by asserting that the eye would only perceive perpendicular rays from the object{{snd}}for any one point on the eye, only the ray that reached it directly, without being refracted by any other part of the eye, would be perceived. He argued, using a physical analogy, that perpendicular rays were stronger than oblique rays: in the same way that a ball thrown directly at a board might break the board, whereas a ball thrown obliquely at the board would glance off, perpendicular rays were stronger than refracted rays, and it was only perpendicular rays which were perceived by the eye. As there was only one perpendicular ray that would enter the eye at any one point, and all these rays would converge on the centre of the eye in a cone, this allowed him to resolve the problem of each point on an object sending many rays to the eye; if only the perpendicular ray mattered, then he had a one-to-one correspondence and the confusion could be resolved.<ref>{{harvnb|Lindberg|1976|p=74}}</ref> He later asserted (in book seven of the ''Optics'') that other rays would be refracted through the eye and perceived ''as if'' perpendicular.<ref>{{harvnb|Lindberg|1976|p=76}}</ref> His arguments regarding perpendicular rays do not clearly explain why ''only'' perpendicular rays were perceived; why would the weaker oblique rays not be perceived more weakly?<ref>{{harvnb|Lindberg|1976|p=75}}</ref> His later argument that refracted rays would be perceived as if perpendicular does not seem persuasive.<ref>{{harvnb|Lindberg|1976|pages=76–78}}</ref> However, despite its weaknesses, no other theory of the time was so comprehensive, and it was enormously influential, particularly in Western Europe. Directly or indirectly, his ''De Aspectibus'' (]) inspired much activity in optics between the 13th and 17th centuries. ]'s later theory of the ]l image (which resolved the problem of the correspondence of points on an object and points in the eye) built directly on the conceptual framework of Alhazen.<ref>{{harvnb|Lindberg|1976|p=86}}.</ref> | |||

| He wrote around 200 books, although very few have survived. Even some of his treatises on optics survived only through Latin translation. During the Middle Ages his books on ] were translated into Latin, ] and other languages. | |||

| Alhazen showed through experiment that light travels in straight lines, and carried out various experiments with ], ]s, ], and ].<ref name="auto">{{harvnb|Al Deek|2004}}.</ref> His analyses of reflection and refraction considered the vertical and horizontal components of light rays separately.<ref>{{harvnb|Heeffer|2003}}.</ref> | |||

| The ] on the Moon was named in his honour<ref name=Gorini/>, as was the ] "]".<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | last = | |||

| | first = | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | coauthors = | |||

| | title = 59239 Alhazen (1999 CR2) | |||

| | work = | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | date = ] | |||

| | url = http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sbdb.cgi?sstr=59239+Alhazen | |||

| | format = | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-09-20}}</ref> Ibn al-Haytham is featured on the obverse of the Iraqi 10,000 dinars banknote issued in 2003,<ref name=csmonitor>{{Harv|Murphy|2003}}</ref> and on 10 dinar notes from 1982. However, a research facility that ] suspected of conducting chemical and biological weapons research in ] Iraq was also named after him.<ref name=csmonitor/><ref>{{Harv|Burns|1999}}</ref> | |||

| Alhazen studied the process of sight, the structure of the eye, image formation in the eye, and the ]. Ian P. Howard argued in a 1996 '']'' article that Alhazen should be credited with many discoveries and theories previously attributed to Western Europeans writing centuries later. For example, he described what became in the 19th century ]. He wrote a description of vertical ]s 600 years before ] that is actually closer to the modern definition than Aguilonius's{{snd}}and his work on ] was repeated by Panum in 1858.<ref>{{harvnb|Howard|1996}}.</ref> Craig Aaen-Stockdale, while agreeing that Alhazen should be credited with many advances, has expressed some caution, especially when considering Alhazen in isolation from ], with whom Alhazen was extremely familiar. Alhazen corrected a significant error of Ptolemy regarding binocular vision, but otherwise his account is very similar; Ptolemy also attempted to explain what is now called Hering's law.<ref>{{harvnb|Aaen-Stockdale|2008}}</ref> In general, Alhazen built on and expanded the optics of Ptolemy.<ref>{{harvnb|Wade|1998|pages=240, 316, 334, 367}}; {{harvnb|Howard|Wade|1996|pages=1195, 1197, 1200}}.</ref> | |||

| ==''Book of Optics''== | |||

| {{main|Book of Optics}} | |||

| In a more detailed account of Ibn al-Haytham's contribution to the study of binocular vision based on Lejeune<ref>{{harvnb|Lejeune|1958}}.</ref> and Sabra,<ref name="{{harvnb|sabra|1989}}.">{{harvnb|Sabra|1989}}.</ref> Raynaud<ref>{{harvnb|Raynaud|2003}}.</ref> showed that the concepts of correspondence, homonymous and crossed diplopia were in place in Ibn al-Haytham's optics. But contrary to Howard, he explained why Ibn al-Haytham did not give the circular figure of the horopter and why, by reasoning experimentally, he was in fact closer to the discovery of Panum's fusional area than that of the Vieth-Müller circle. In this regard, Ibn al-Haytham's theory of binocular vision faced two main limits: the lack of recognition of the role of the retina, and obviously the lack of an experimental investigation of ocular tracts. | |||

| Ibn al-Haytham's most famous work is his seven volume ] on ], ''Kitab al-Manazir'' (''Book of Optics''), written from 1011 to 1021.<ref name="Review first">{{Harv|Steffens|2006}} (] {{cite web|url=http://www.ibnalhaytham.net/custom.em?pid=571860|title=Critical Praise for ''Ibn al-Haytham - First Scientist''|date=2006-12-01|accessdate=2008-01-23}})</ref> It has been ranked alongside ]'s '']'' as one of the most influential books in physics<ref name=Salih/> for introducing an early scientific method, and for initiating a ] in optics<ref name=Hogendijk>{{Harv|Sabra|Hogendijk|2003|pp=85–118}}</ref> and ].<ref name=Ragep>{{Harv|Hatfield|1996|p=500}}</ref> | |||

| ] according to Ibn al-Haytham. Note the depiction of the ]. —Manuscript copy of his ] (MS Fatih 3212, vol. 1, fol. 81b, ] Library, Istanbul)]] | |||

| ''Optics'' was ] by an unknown scholar at the end of the 12th century or the beginning of the 13th century.<ref>{{Harv|Crombie|1971|p=147, n. 2}}</ref> It was printed by ] in 1572, with the title ''Opticae thesaurus: Alhazeni Arabis libri septem, nuncprimum editi; Eiusdem liber De Crepusculis et nubium ascensionibus''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mala.bc.ca/~mcneil/cit/citlcalhazen1.htm|title=Alhazen (965-1040): Library of Congress Citations|publisher=Malaspina Great Books|accessdate=2008-01-23}}</ref> Risner is also the author of the name variant "Alhazen"; before Risner he was known in the west as Alhacen, which is the correct transcription of the Arabic name.<ref>{{Harv|Smith|2001|p=xxi}}</ref> This work enjoyed a great reputation during the ]. Works by Ibn al-Haytham on geometric subjects were discovered in the ] in ] in 1834 by E. A. Sedillot. Other manuscripts are preserved in the ] at ] and in the library of ]. Ibn al-Haytham's optical studies were influential in several later developments, including the ], which laid the foundations of telescopic astronomy,<ref name=Marshall/> as well as of the modern ], the ], and the use of optical aids in ] art.<ref name=Power/> | |||

| Alhazen's most original contribution was that, after describing how he thought the eye was anatomically constructed, he went on to consider how this anatomy would behave functionally as an optical system.<ref>{{harvnb|Russell|1996|p=691}}.</ref> His understanding of ] from his experiments appears to have influenced his consideration of image inversion in the eye,<ref>{{harvnb|Russell|1996|p=689}}.</ref> which he sought to avoid.<ref>{{harvnb|Lindberg|1976|pages= 80–85}}</ref> He maintained that the rays that fell perpendicularly on the lens (or glacial humor as he called it) were further refracted outward as they left the glacial humor and the resulting image thus passed upright into the optic nerve at the back of the eye.<ref>{{harvnb|Smith|2004|pages=186, 192}}.</ref> He followed ] in believing that the ] was the receptive organ of sight, although some of his work hints that he thought the ] was also involved.<ref>{{harvnb|Wade|1998|p=14}}</ref> | |||

| Alhazen's synthesis of light and vision adhered to the Aristotelian scheme, exhaustively describing the process of vision in a logical, complete fashion.<ref>{{Cite journal|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/3657357|title=Alhacen's Theory of Visual Perception: A Critical Edition, with English Translation and Commentary, of the First Three Books of Alhacen's "De aspectibus", the Medieval Latin Version of Ibn al-Haytham's "Kitāb al-Manāẓir": Volume Two|author=Smith, A. Mark|year=2001|journal=Transactions of the American Philosophical Society|volume=91|issue=5|pages=339–819|doi=10.2307/3657357|jstor=3657357|access-date=12 January 2015|archive-date=30 June 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150630235046/http://www.jstor.org/stable/3657357?|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Optics=== | |||

| ] in his '']'' (1021).]] | |||

| His research in ] (the study of optical systems using mirrors) was centred on spherical and ] mirrors and ]. He made the observation that the ratio between the ] and ] does not remain constant, and investigated the ] power of a ].<ref name="auto" /> | |||

| Two major theories on vision prevailed in ]. The first theory, the ], was supported by such thinkers as ] and ], who believed that sight worked by the eye emitting ] of ]. The second theory, the intromission theory supported by ] and his followers, had physical forms entering the eye from an object. Ibn al-Haytham argued that the process of vision occurs neither by rays emitted from the eye, nor through physical forms entering it. He reasoned that a ray could not proceed from the eyes and reach the distant stars the instant after we open our eyes. He also appealed to common observations such as the eye being dazzled or even injured if we look at a very bright light. He instead developed a highly successful theory which explained the process of vision as rays of light proceeding to the eye from each point on an object, which he proved through the use of ]ation.<ref>{{Harv|Lindberg|1976|pp=60–7}}</ref> His unification of ] with ] forms the basis of modern ].<ref>{{Harv|Toomer|1964}}</ref> | |||

| === Law of reflection === | |||

| Ibn al-Haytham proved that rays of light travel in straight lines, and carried out various experiments with ], ]s, ], and ].<ref name=Deek/> He was also the first to reduce reflected and refracted light rays into vertical and horizontal components, which was a fundamental development in geometric optics.<ref>{{Harv|Heeffer|2003}}</ref> He also discovered a result similar to ] of sines, but did not quantify it and derive the law mathematically.<ref>{{Harv|Sabra|1981}} (] {{Harv|Mihas|2005|p=5}})</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Specular reflection}} | |||

| Alhazen was the first physicist to give complete statement of the law of reflection.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Stamnes |first=J. J. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dGQ-DwAAQBAJ&dq=alhazen+law+of+reflection&pg=PT15 |title=Waves in Focal Regions: Propagation, Diffraction and Focusing of Light, Sound and Water Waves |date=2017 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-351-40468-6 |language=en |access-date=22 February 2023 |archive-date=31 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230331171120/https://books.google.com/books?id=dGQ-DwAAQBAJ&dq=alhazen+law+of+reflection&pg=PT15 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Mach |first=Ernst |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7dPCAgAAQBAJ&dq=alhazen+incident+ray+reflected+ray+lie+on+same+plane&pg=PA29 |title=The Principles of Physical Optics: An Historical and Philosophical Treatment |date=2013 |publisher=Courier Corporation |isbn=978-0-486-17347-4 |language=en |access-date=22 February 2023 |archive-date=31 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230331172406/https://books.google.com/books?id=7dPCAgAAQBAJ&dq=alhazen+incident+ray+reflected+ray+lie+on+same+plane&pg=PA29 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Iizuka |first=Keigo |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h9n6CAAAQBAJ&dq=alhazen+law+of+reflection&pg=PA7 |title=Engineering Optics |date=2013 |publisher=Springer Science & Business Media |isbn=978-3-662-07032-1 |language=en |access-date=22 February 2023 |archive-date=31 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230331171118/https://books.google.com/books?id=h9n6CAAAQBAJ&dq=alhazen+law+of+reflection&pg=PA7 |url-status=live }}</ref> He was first to state that the incident ray, the reflected ray, and the normal to the surface all lie in a same plane perpendicular to reflecting plane.{{sfn|Selin|2008|p=1817}}<ref>{{Cite book |last=Mach |first=Ernst |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7dPCAgAAQBAJ&dq=alhazen+first+incident+ray+reflected+ray+lie+on+same+plane&pg=PA29 |title=The Principles of Physical Optics: An Historical and Philosophical Treatment |date=2013 |publisher=Courier Corporation |isbn=978-0-486-17347-4 |language=en |access-date=22 February 2023 |archive-date=31 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230331171118/https://books.google.com/books?id=7dPCAgAAQBAJ&dq=alhazen+first+incident+ray+reflected+ray+lie+on+same+plane&pg=PA29 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Alhazen's problem === | |||

| Ibn al-Haytham also gave the first clear description<ref name=Kelley>{{Harv|Kelley|Milone|Aveni|2005}}: {{quote|"The first clear description of the device appears in the ''Book of Optics'' of Alhazen."}}</ref> and correct analysis<ref name=Wade>{{Harv|Wade|Finger|2001}}: {{quote|"The principles of the camera obscura first began to be correctly analysed in the eleventh century, when they were outlined by Ibn al-Haytham."}}</ref> of the ] and ]. While ], ], ] (Alkindus) and ] ] had earlier described the effects of a single light passing through a pinhole, none of them suggested that what is being projected onto the screen is an image of everything on the other side of the ]. Ibn al-Haytham was the first to demonstrate this with his lamp experiment where several different light sources are arranged across a large area. He was thus the first to successfully project an entire image from outdoors onto a screen indoors with the camera obscura.<ref>{{Harv|Steffens|2006}}, </ref> | |||

| {{Main|Alhazen's problem}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| His work on ] in Book V of the Book of Optics contains a discussion of what is now known as Alhazen's problem, first formulated by ] in 150 AD. It comprises drawing lines from two points in the ] of a circle meeting at a point on the ] and making equal angles with the ] at that point. This is equivalent to finding the point on the edge of a circular ] at which a player must aim a cue ball at a given point to make it bounce off the table edge and hit another ball at a second given point. Thus, its main application in optics is to solve the problem, "Given a light source and a spherical mirror, find the point on the mirror where the light will be reflected to the eye of an observer." This leads to an ].<ref>{{harvnb|O'Connor|Robertson|1999}}, {{harvnb|Weisstein|2008}}.</ref> This eventually led Alhazen to derive a formula for the sum of ]s, where previously only the formulas for the sums of squares and cubes had been stated. His method can be readily generalized to find the formula for the sum of any integral powers, although he did not himself do this (perhaps because he only needed the fourth power to calculate the volume of the paraboloid he was interested in). He used his result on sums of integral powers to perform what would now be called an ], where the formulas for the sums of integral squares and fourth powers allowed him to calculate the volume of a ].<ref>{{harvnb|Katz|1995|pp=165–169, 173–174}}.</ref> Alhazen eventually solved the problem using ]s and a geometric proof. His solution was extremely long and complicated and may not have been understood by mathematicians reading him in Latin translation. | |||

| Later mathematicians used ]' analytical methods to analyse the problem.<ref>{{harvnb|Smith|1992}}.</ref> An algebraic solution to the problem was finally found in 1965 by Jack M. Elkin, an actuarian.<ref>{{Citation|last=Elkin|first=Jack M.|title=A deceptively easy problem|journal=Mathematics Teacher|volume=58|issue=3|pages=194–199|year=1965|doi=10.5951/MT.58.3.0194|jstor=27968003}}</ref> Other solutions were discovered in 1989, by Harald Riede<ref>{{Citation|last=Riede|first=Harald|title=Reflexion am Kugelspiegel. Oder: das Problem des Alhazen|journal=Praxis der Mathematik|volume=31|issue=2|pages=65–70|year=1989|language=de}}</ref> and in 1997 by the ] mathematician ].<ref>{{Citation|last=Neumann|first=Peter M.|author-link=Peter M. Neumann|title=Reflections on Reflection in a Spherical Mirror|journal=]|volume=105|issue=6|pages=523–528|year=1998|jstor=2589403|mr=1626185|doi=10.1080/00029890.1998.12004920}}</ref><ref>{{Citation|last=Highfield |first=Roger |author-link=Roger Highfield |date=1 April 1997 |title=Don solves the last puzzle left by ancient Greeks |journal=] |volume=676 |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/htmlContent.jhtml?html=/archive/1997/04/01/ngre01.html|url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20041123051228/http://www.telegraph.co.uk/htmlContent.jhtml?html=%2Farchive%2F1997%2F04%2F01%2Fngre01.html |archive-date=23 November 2004 }}</ref> | |||

| Recently, ] (MERL) researchers solved the extension of Alhazen's problem to general rotationally symmetric quadric mirrors including hyperbolic, parabolic and elliptical mirrors.<ref>{{harvnb|Agrawal|Taguchi|Ramalingam|2011}}.</ref> | |||

| === Camera Obscura === | |||

| In addition to physical optics, ''The Book of Optics'' also gave rise to the field of "physiological optics".<ref name=Russell-689>Gul A. Russell, "Emergence of Physiological Optics", p. 689, in {{Harv|Morelon|Rashed|1996}}</ref> Ibn al-Haytham discussed the topics of ], ], ] and ], which included commentaries on ]ic works.<ref>{{Harv|Steffens|2006}} (] {{cite web|url=http://ummahpulse.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=85&Itemid=54|title=Review by Sulaiman Awan|accessdate=2008-01-23}})</ref> He described the process of sight,<ref>{{Harv|Saad|Azaizeh|Said|2005|p=476}}</ref> the structure of the eye, image formation in the eye, and the ]. He also described what became known as ], vertical ]s, and ],<ref name=Howard>{{Harv|Howard|1996}}</ref> and improved on the theories of ], ] and horopters previously discussed by ], ] and ].<ref name=Wade-1998>{{Harv|Wade|1998}}</ref><ref name=Howard-Wade-1996>{{Harv|Howard|Wade|1996}}</ref> | |||

| The ] was known to the ], and was described by the ] ] ] in his scientific book '']'', published in the year 1088 C.E. ] had discussed the basic principle behind it in his ''Problems'', but Alhazen's work contained the first clear description of ].<ref>{{harvnb|Kelley|Milone|Aveni|2005|p=83}}: "The first clear description of the device appears in the ''Book of Optics'' of Alhazen."</ref> and early analysis<ref>{{harvnb|Wade|Finger|2001}}: "The principles of the camera obscura first began to be correctly analysed in the eleventh century, when they were outlined by Ibn al-Haytham."</ref> of the device. | |||

| Ibn al-Haytham used a ] mainly to observe a partial solar eclipse.<ref>German physicist Eilhard Wiedemann first provided an abridged German translation of ''On the shape of the eclipse'': {{Cite journal |author=Eilhard Wiedemann |title=Über der Camera obscura bei Ibn al Haiṭam |journal=Sitzungsberichte phys.-med. Sozietät in Erlangen |year=1914 |volume=46 | pages=155–169}} The work is now available in full: {{harvnb|Raynaud|2016}}.</ref> | |||

| His most original anatomical contribution was his description of the functional anatomy of the eye as an optical system,<ref>Gul A. Russell, "Emergence of Physiological Optics", p. 691, in {{Harv|Morelon|Rashed|1996}}</ref> or optical instrument. His experiments with the camera obscura provided sufficient ] grounds for him to develop his theory of corresponding point projection of light from the surface of an object to form an image on a screen. It was his comparison between the eye and the camera obscura which brought about his synthesis of anatomy and optics, which forms the basis of physiological optics. As he conceptualized the essential principles of pinhole projection from his experiments with the pinhole camera, he considered image inversion to also occur in the eye,<ref name=Russell-689/> and viewed the ] as being similar to an aperture.<ref>Gul A. Russell, "Emergence of Physiological Optics", p. 695-8, in {{Harv|Morelon|Rashed|1996}}</ref> Regarding the process of image formation, he incorrectly agreed with ] that the ] was the receptive organ of sight, but correctly hinted at the ] being involved in the process.<ref name=Wade-1998/> | |||

| In his essay, Ibn al-Haytham writes that he observed the sickle-like shape of the sun at the time of an eclipse. The introduction reads as follows: "The image of the sun at the time of the eclipse, unless it is total, demonstrates that when its light passes through a narrow, round hole and is cast on a plane opposite to the hole it takes on the form of a moonsickle." | |||

| It is admitted that his findings solidified the importance in the history of the ]<ref>{{Cite book|title=History of Photography|last=Eder|first=Josef|publisher=Columbia University Press|year=1945|location=New York|page=37}}</ref> but this treatise is important in many other respects. | |||

| ===Scientific method=== | |||

| Neuroscientist Rosanna Gorini notes that "according to the majority of the historians al-Haytham was the pioneer of the modern ]."<ref name=Gorini>{{Harv|Gorini|2003}}</ref><ref>{{Harv|Rashed|2002a|p=773}}</ref> Ibn al-Haytham developed rigorous experimental methods of controlled ] to verify theoretical hypotheses and substantiate ] ]s.<ref name=Bizri/> Ibn al-Haytham's scientific method was very similar to the modern scientific method and consisted of the following procedures:<ref name=Ezine/> | |||

| #] | |||

| #Statement of ] | |||

| #Formulation of ] | |||

| #Testing of hypothesis using ]ation | |||

| #Analysis of experimental ]s | |||

| #Interpretation of ] and formulation of ] | |||

| #] of findings | |||

| Ancient optics and medieval optics were divided into optics and burning mirrors. Optics proper mainly focused on the study of vision, while burning mirrors focused on the properties of light and luminous rays. ''On the shape of the eclipse'' is probably one of the first attempts made by Ibn al-Haytham to articulate these two sciences. | |||

| An aspect associated with Ibn al-Haytham's optical research is related to systemic and methodological reliance on experimentation (''i'tibar'') and ] in his scientific inquiries. Moreover, his experimental directives rested on combining classical physics ('''ilm tabi'i'') with mathematics (''ta'alim''; geometry in particular) in terms of devising the rudiments of what may be designated as a ] in scientific research. This mathematical-physical approach to experimental science supported most of his propositions in ''Kitab al-Manazir'' (''The Optics''; ''De aspectibus'' or ''Perspectivae'') and grounded his theories of vision, light and colour, as well as his research in catoptrics and ] (the study of the refraction of light). His legacy was further advanced through the 'reforming' of his ''Optics'' by ] (d. ca. 1320) in the latter's ''Kitab Tanqih al-Manazir'' (''The Revision of'' ''Optics'').<ref name=Steffens/><ref name=Bizri-2005>{{Harv|El-Bizri|2005a}} <br> {{Harv|El-Bizri|2005b}}</ref> | |||

| Very often Ibn al-Haytham's discoveries benefited from the intersection of mathematical and experimental contributions. This is the case with ''On the shape of the eclipse''. Besides the fact that this treatise allowed more people to study partial eclipses of the sun, it especially allowed to better understand how the camera obscura works. This treatise is a physico-mathematical study of image formation inside the camera obscura. Ibn al-Haytham takes an experimental approach, and determines the result by varying the size and the shape of the aperture, the focal length of the camera, the shape and intensity of the light source.<ref>{{harvnb|Raynaud|2016|pp=130–160}}</ref> | |||

| The concept of ] is also present in the ''Book of Optics''. For example, after demonstrating that light is generated by luminous objects and emitted or reflected into the eyes, he states that therefore "the ] of rays is superflous and useless."<ref>{{Harv|Smith|2001|pp=372 & 408}}</ref> | |||

| In his work he explains the inversion of the image in the camera obscura,<ref>{{harvnb|Raynaud|2016|pp=114–116}}</ref> the fact that the image is similar to the source when the hole is small, but also the fact that the image can differ from the source when the hole is large. All these results are produced by using a point analysis of the image.<ref>{{harvnb|Raynaud|2016|pp=91–94}}</ref> | |||

| ===Alhazen's problem=== | |||

| His work on ] in Book V of the Book of Optics contains a discussion of what is now known as Alhazen's problem, first formulated by ] in 150 AD. It comprises drawing lines from two points in the ] of a circle meeting at a point on the ] and making equal angles with the ] at that point. This is equivalent to finding the point on the edge of a circular ] at which a cue ball at a given point must be aimed in order to canon off the edge of the table and hit another ball at a second given point. Thus, its main application in optics is to solve the problem, "Given a light source and a spherical mirror, find the point on the mirror were{{sic}} the light will be reflected to the eye of an observer." This leads to an ].<ref name=MacTutor/><ref>{{cite web | |||

| | last = Weisstein | |||

| | first = Eric | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | coauthors = | |||

| | title = Alhazen's Billiard Problem | |||

| | work = | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | date = | |||

| | url = http://mathworld.wolfram.com/AlhazensBilliardProblem.html | |||

| | format = | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-09-24}}</ref> This eventually led Ibn al-Haytham to derive the earliest formula for the sum of ]s; by using an early ] by ], he developed a method that can be readily generalized to find the formula for the sum of any integral powers. He applied his result of sums on integral powers to find the volume of a ] through ]. He was thus able to find the ]s for ]s up to the ], and came close to finding a general formula for the integrals of any polynomials. This was fundamental to the development of ] and integral ].<ref name=Katz>{{Harv|Katz|1995|pp=165-9 & 173-4}}</ref> Ibn al-Haytham eventually solved the problem using ]s and a geometric proof, though many after him attempted to find an algebraic solution to the problem,<ref name=Smith/> until it was eventually solved by the end of the 20th century.<ref name=Steffens/> | |||

| === |

=== Refractometer === | ||

| {{Main|Refractometer}} | |||

| Chapters 15–16 of the ''Book of Optics'' covered ]. Ibn al-Haytham was the first to discover that the ] do not consist of ] matter. He also discovered that the heavens are less dense than the air. These views were later repeated by ] and had a significant influence on the ] and ]s of astronomy.<ref>{{Harv|Rosen|1985|pp=19–21}}</ref> | |||

| In the seventh tract of his book of optics, Alhazen described an apparatus for experimenting with various cases of refraction, in order to investigate the relations between the angle of incidence, the angle of refraction and the angle of deflection. This apparatus was a modified version of an apparatus used by Ptolemy for similar purpose.<ref>{{Cite book |url=http://archive.org/details/history-of-science-and-technology-in-islam-fuat-sezgin |title=History Of Science And Technology In Islam Fuat Sezgin |date=2011}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Gaukroger |first=Stephen |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QVwDs_Ikad0C&dq=ptolemy+alhazen+refractometer&pg=PA142 |title=Descartes: An Intellectual Biography |date=1995 |publisher=Clarendon Press |isbn=978-0-19-151954-3 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Newton |first=Isaac |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gNrLQN0VbAoC&dq=ptolemy+alhazen+refractometer&pg=PA175 |title=The Optical Papers of Isaac Newton|volume =1: The Optical Lectures 1670–1672 |date=1984|publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-25248-5 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| === Unconscious inference === | |||

| In ], Ibn al-Haytham is considered a pioneer of ]. He articulated a relationship between the physical and observable ] and that of ], ] and ]s. His theories regarding ] and ], linking the domains of science and religion, led to a philosophy of ] based on the direct observation of ] from the observer's point of view.<ref>{{Harv|Dr. Gonzalez|2002}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Unconscious inference}} | |||

| Alhazen basically states the concept of unconscious inference in his discussion of colour before adding that the inferential step between sensing colour and differentiating it is shorter than the time taken between sensing and any other visible characteristic (aside from light), and that "time is so short as not to be clearly apparent to the beholder." Naturally, this suggests that the colour and form are perceived elsewhere. Alhazen goes on to say that information must travel to the central nerve cavity for processing and:<blockquote>the sentient organ does not sense the forms that reach it from the visible objects until | |||

| after it has been affected by these forms; thus it does not sense color as color or light as light until after it has been affected by the form of color or light. Now the affectation received by the sentient organ from the form of color or of light is a certain change; and change must take place in time; .....and it is in the time during which the form extends from the sentient organ's surface to the cavity of the common nerve, and in (the time) following that, that the sensitive faculty, which exists in the whole of the sentient body will perceive color as color...Thus the last sentient's perception of color as such and of light as such takes place at a time following that in which the form arrives from the surface of the sentient organ to the cavity of the common nerve.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Boudrioua |first1=Azzedine |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WD0PEAAAQBAJ&dq=the+sentient+organ+does+not+sense+the+forms+that+reach+it+from+the+visible+objects+until+after+it+has+been+a&pg=PA76 |title=Light-Based Science: Technology and Sustainable Development, The Legacy of Ibn al-Haytham |last2=Rashed |first2=Roshdi |last3=Lakshminarayanan |first3=Vasudevan |date=2017 |publisher=CRC Press |isbn=978-1-4987-7940-1 |language=en}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| === Color constancy === | |||

| In ], Ibn al-Haytham is considered the founder of ] by ],<ref name=Khaleefa/> for his pioneering work on the psychology of visual perception and ]s.<ref name=Steffens/> In the '']'', Ibn al-Haytham was the first scientist to argue that vision occurs in the brain, rather than the eyes. He pointed out that personal experience has an effect on what people see and how they see, and that vision and perception are subjective.<ref name=Steffens/> | |||

| {{Main|Color constancy}} | |||

| Alhazen explained ] by observing that the light reflected from an object is modified by the object's color. He explained that the quality of the light and the color of the object are mixed, and the visual system separates light and color. In Book II, Chapter 3 he writes:<blockquote>Again the light does not travel from the colored object to the eye unaccompanied by the color, nor does the form of the color pass from the colored object to the eye unaccompanied by the light. Neither the form of the light nor that of the color existing in the colored object can pass except as mingled together and the last sentient can only | |||

| perceive them as mingled together. Nevertheless, the sentient perceives that the visible object is luminous and that the light seen in the object is other than the color and that these are two properties.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Boudrioua |first1=Azzedine |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WD0PEAAAQBAJ&dq=Al-Haytham+described+color+constancy+by+observing+that+light+reflected+by+an+object+is+modified+by+the+color+of+the+object&pg=PA78 |title=Light-Based Science: Technology and Sustainable Development, The Legacy of Ibn al-Haytham |last2=Rashed |first2=Roshdi |last3=Lakshminarayanan |first3=Vasudevan |date=2017|publisher=CRC Press |isbn=978-1-4987-7940-1 |language=en}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| === Other contributions === | |||

| He came up with a theory to explain the ], which played an important role in the scientific tradition of medieval Europe. It was an attempt to the solve the problem of the Moon appearing larger near the horizon than it does while higher up in the sky. Arguing against Ptolemy's refraction theory, he redefined the problem in terms of perceived, rather than real, enlargement. He said that judging the distance of an object depends on there being an uninterrupted sequence of intervening bodies between the object and the observer. With the Moon however, there are no intervening objects. Therefore, since the size of an object depends on its observed distance, which is in this case inaccurate, the Moon appears larger on the horizon. Through works by ], ] and ] based on Ibn al-Haytham's explanation, the Moon illusion gradually came to be accepted as a psychological phenomenon, with Ptolemy's theory being rejected in the 17th century.<ref>{{Harv|Hershenson|1989| pp=9–10}}</ref> | |||

| The ''Kitab al-Manazir'' (Book of Optics) describes several experimental observations that Alhazen made and how he used his results to explain certain optical phenomena using mechanical analogies. He conducted experiments with ]s and concluded that only the impact of ] projectiles on surfaces was forceful enough to make them penetrate, whereas surfaces tended to deflect ] projectile strikes. For example, to explain refraction from a rare to a dense medium, he used the mechanical analogy of an iron ball thrown at a thin slate covering a wide hole in a metal sheet. A perpendicular throw breaks the slate and passes through, whereas an oblique one with equal force and from an equal distance does not.<ref>{{harvnb|Russell|1996|p=695}}.</ref> He also used this result to explain how intense, direct light hurts the eye, using a mechanical analogy: Alhazen associated 'strong' lights with perpendicular rays and 'weak' lights with oblique ones. The obvious answer to the problem of multiple rays and the eye was in the choice of the perpendicular ray, since only one such ray from each point on the surface of the object could penetrate the eye.<ref>{{harvnb|Russell|1996|p=}}.</ref> | |||

| Omar Khaleefa has argued that |

Sudanese psychologist Omar Khaleefa has argued that Alhazen should be considered the founder of ], for his pioneering work on the psychology of visual perception and ]s.<ref name="auto2">{{harvnb|Khaleefa|1999}}</ref> Khaleefa has also argued that Alhazen should also be considered the "founder of ]", a sub-discipline and precursor to modern psychology.<ref name="auto2" /> Although Alhazen made many subjective reports regarding vision, there is no evidence that he used quantitative psychophysical techniques and the claim has been rebuffed.<ref>{{harvnb|Aaen-Stockdale|2008}}.</ref> | ||

| Alhazen offered an explanation of the ], an illusion that played an important role in the scientific tradition of medieval Europe.<ref>{{harvnb|Ross|Plug|2002}}.</ref> Many authors repeated explanations that attempted to solve the problem of the Moon appearing larger near the horizon than it does when higher up in the sky. Alhazen argued against Ptolemy's refraction theory, and defined the problem in terms of perceived, rather than real, enlargement. He said that judging the distance of an object depends on there being an uninterrupted sequence of intervening bodies between the object and the observer. When the Moon is high in the sky there are no intervening objects, so the Moon appears close. The perceived size of an object of constant angular size varies with its perceived distance. Therefore, the Moon appears closer and smaller high in the sky, and further and larger on the horizon. Through works by ], ] and Witelo based on Alhazen's explanation, the Moon illusion gradually came to be accepted as a psychological phenomenon, with the refraction theory being rejected in the 17th century.<ref>{{harvnb|Hershenson|1989|pp=9–10}}.</ref> Although Alhazen is often credited with the perceived distance explanation, he was not the first author to offer it. ] ({{circa}} 2nd century) gave this account (in addition to refraction), and he credited it to ] ({{circa}} 135–50 BCE).<ref>{{harvnb|Ross|2000}}.</ref> Ptolemy may also have offered this explanation in his ''Optics'', but the text is obscure.<ref>{{harvnb|Ross|Ross|1976}}.</ref> Alhazen's writings were more widely available in the Middle Ages than those of these earlier authors, and that probably explains why Alhazen received the credit. | |||

| ==Other works on physics== | |||

| ===Optical treatises=== | |||

| Besides the ''Book of Optics'', Ibn al-Haytham wrote several other treatises on ]. His ''Risala fi l-Daw’'' (''Treatise on Light'') is a supplement to his ''Kitab al-Manazir'' (''Book of Optics''). The text contained further investigations on the properties of ] and its ] dispersion through various ] media. He also carried out further examinations into anatomy of the ] and ] in ]. He analyzed the ] and ], and investigated the ] of the ] and the ] of the atmosphere. Various ] phenomena (including the ], twilight, and ]) were also examined by him. He also made investigations into ], ], ], ] and ] mirrors, and ].<ref name=Bizri/> | |||

| == Scientific method == | |||

| In his treatise, ''Mizan al-Hikmah'' (''Balance of Wisdom''), Ibn al-Haytham discussed the ] of the ] and related it to ]. He also studied ]. He discovered that the ] only ceases or begins when the Sun is 19° below the horizon and attempted to measure the height of the atmosphere on that basis.<ref name=Deek>{{Harv|Dr. Al Deek|2004}}</ref> | |||