| Revision as of 12:13, 9 December 2005 view sourceFT2 (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Administrators55,546 editsm →Academic and professional: german paper - add proper links and clean up English← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:41, 8 January 2025 view source Delderd (talk | contribs)280 edits →Research perspectivesTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Paraphilia involving a sexual fixation on non-human animals}} | |||

| ]'', a ] copy after a lost painting by ], 1530 (])]] | |||

| {{Distinguish|Zoophily}} | |||

| ''This article is about zoophilia and bestiality. For other meanings please see ] or . | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| {{Lead too short|date=November 2023}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2021}} | |||

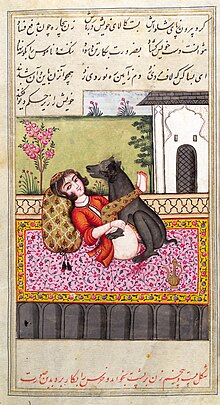

| ]}} by F.K. Forberg, illustrated by ]]] | |||

| '''Zoophilia''' is a ] in which a person experiences a sexual fixation on non-human animals.<ref name="DSM 5" /><ref>{{Cite web |last=P. Rafferty |first=John |date=21 September 2022 |title=Zoophilia |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/zoophilia |access-date=9 January 2023 |website=Encyclopedia Britannica}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Krause |first1=Caitlin E. |title=Encyclopedia of Sexual Psychology and Behavior |date=2023 |publisher=Springer, Cham |isbn=978-3-031-08956-5 |pages=1–4 |url=https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-031-08956-5_88-1 |language=en |chapter=Zoophilia |doi=10.1007/978-3-031-08956-5_88-1}}</ref> '''Bestiality''' instead refers to cross-species sexual activity between humans and non-human animals.{{efn|name=Note01|The terms are often used interchangeably, but it is important to make a distinction between the attraction (zoophilia) and the act (bestiality).<ref name="ranger">{{cite journal |last1 = Ranger |first1=R. |last2=Fedoroff |first2=P. | year = 2014 | title = Commentary: Zoophilia and the Law | journal = Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online | volume = 42 | issue = 4 | pages = 421–426 | url = http://www.jaapl.org/content/42/4/421.full | pmid = 25492067}}</ref>}} Due to the lack of research on the subject, it is difficult to conclude how prevalent bestiality is.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Holoyda |first1=Brian |last2=Sorrentino |first2=Renee |last3=Hatters Friedman |first3=Susan |last4=Allgire |first4=John |date=2018 |title=Bestiality: An introduction for legal and mental health professionals |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30306630/ |access-date=8 January 2023 |journal=Behavioral Sciences & the Law|volume=36 |issue=6 |pages=687–697 |doi=10.1002/bsl.2368 |pmid=30306630 |s2cid=52957702 }}</ref> Zoophilia, however, was estimated in one study to be prevalent in 2% of the population in 2021.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| == History == | |||

| '''Zoophilia''' (from the ] ''Zoon'', "animal", and ''Philia'', "friendship" or "love") is a ], defined as an affinity or ] by a ] to ]s. Such individuals are called '''zoophiles'''. The more recent terms '''zoosexual''' and '''zoosexuality''' also describe the full spectrum of human/animal attraction. A separate term, '''bestiality''' (more common in mainstream usage), refers to human/animal sexual activity. To avoid confusion about the meaning of ''zoophilia'' – which may refer to the affinity/attraction, paraphilia, or sexual activity – this article uses ''zoophilia'' for the former, and ''zoosexuality'' for the sexual act. The two terms are independent: not all sexual acts with animals are performed by zoophiles, not all zoophiles are interested in being sexual with animals. | |||

| {{See also|History of zoophilia}} | |||

| The historical perspective on zoophilia and bestiality varies greatly, from the ], where depictions of bestiality appear in European ],<ref name="Bahn1998" /> to the Middle Ages, where bestiality was met with execution. In many parts of the world, bestiality is illegal under ] laws or laws dealing with ] or ]. | |||

| Zoophilia is usually considered to be unnatural, and sexual acts with animals are often condemned as ] and/or outlawed as "crimes against nature". However, some, such as philosopher and animal rights author ], argue that this is not inherently the case. Although research has broadly been supportive of at least some of zoophiles' central claims, common culture is generally hostile to the concept of animal-human sexuality. | |||

| The activity or desire itself is no longer classified as a pathology under ] (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the ]) unless accompanied by distress or interference with normal functioning on the part of the person. Critics point out that that DSM-IV opinion says nothing about acceptability or the well being of the animal; defenders, on the other hand, argue that a human/animal relationship can go far beyond sexuality, that research supports their perspective, and that animals are capable of forming what is claimed to be a genuine ] that can last for years and is not considered functionally different from any other love/sex relationship. | |||

| == Terminology == | == Terminology == | ||

| ===General=== | |||

| Three key terms commonly used in regards to the subject—''zoophilia'', ''bestiality'', and ''zoosexuality''—are often used somewhat interchangeably. Some researchers distinguish between zoophilia (as a persistent sexual interest in animals) and bestiality (as sexual acts with animals), because bestiality is often not driven by a sexual preference for animals.<ref name="ranger" /> Some studies have found a preference for animals is rare among people who engage in sexual contact with animals.<ref name="earls">{{cite journal |doi=10.1177/107906320201400106 |pmid=11803597 |title=A Case Study of Preferential Bestiality (Zoophilia) |year=2002 |last1=Earls |first1=C. M. |last2=Lalumiere |first2=M. L. |journal=Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment |volume=14 |issue=1 |pages=83–88|s2cid=43450855 }}</ref> Furthermore, some zoophiles report they have never had sexual contact with an animal.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Maratea, R. J. |year=2011 |title=Screwing the pooch: Legitimizing accounts in a zoophilia on-line community |journal=Deviant Behavior |volume=32 |issue=10 |page=938 |doi=10.1080/01639625.2010.538356| s2cid=145637418}}</ref> People with zoophilia are known as "zoophiles", though also sometimes as "zoosexuals", or even very simply "zoos".<ref name="ranger" /><ref name="Handbookth">{{Cite book |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=G_MwT9OHj4AC&q=zoophilia&pg=PA201 |title=The International Handbook of Animal Abuse and Cruelty: Theory, Research, and Application |chapter=Bestiality and Zoophilia: A Discussion of Sexual Contact With Animals |isbn=978-1-55753-565-8 |editor=Ascione, Frank |author=Beetz, Andrea M. |year=2010| publisher=Purdue University Press}}</ref> ''Zooerasty'', '']'', and ''zooerastia''<ref>{{cite web |title=zooerastia definition |url=http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/zooerastia |website=Dictionary.com|access-date=13 December 2011}}</ref> are other terms closely related to the subject but are less synonymous with the former terms, and are seldom used. "Bestiosexuality" was discussed briefly by Allen (1979), but never became widely established.{{citation needed|date=February 2014}}] depicting ] having sex with a fawn, dated after 500 BC.]] | |||

| ] coined the separate term ''zoosadism'' for those who derive pleasure – sexual or otherwise – from inflicting pain on animals. Zoosadism specifically is one member of the ] of precursors to ].<ref name="MacDonald">{{cite journal |last=MacDonald |first=J. M. |title=The Threat to Kill |journal=American Journal of Psychiatry |year=1963 |volume=120 |issue=2 |pages=125–30 |url=http://journals.psychiatryonline.org/article.aspx?articleid=149172 |access-date=19 January 2013 |doi=10.1176/ajp.120.2.125 |archive-date=26 July 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140726125253/http://journals.psychiatryonline.org/article.aspx?articleid=149172}}</ref> | |||

| ===Zoophilia=== | |||

| The general term "zoophilia" was first introduced into the field of research on sexuality by ] (1894). The terms '''zoosexual''' and '''zoosexuality''', signifying the entire spectrum of emotional and sexual attraction and/or orientation to animals, have been used since the ] (cited by Miletski, 1999), to suggest an analogy to homosexual or heterosexual orientations. Individuals with a strong affinity for animals but without a sexual interest can be described as "non-sexual" (or "emotional") zoophiles, but may object to the "zoophile" label. They are commonly called ''']rs''' instead. | |||

| The term ''zoophilia'' was introduced into the field of research on sexuality in '']'' (1886) by ], who described a number of cases of "violation of animals (bestiality)",<ref>Richard von Krafft-Ebing: ], p. 561.</ref> as well as "zoophilia erotica",<ref>Richard von Krafft-Ebing: ], p. 281.</ref> which he defined as a sexual attraction to animal skin or fur. The term ''zoophilia'' derives from the combination of two nouns in ]: '''''ζῷον''''' (''zṓion'', meaning "animal") and '''''φιλία''''' ('']'', meaning "(fraternal) love"). In general contemporary usage, the term ''zoophilia'' may refer to sexual activity between human and non-human animals, the desire to engage in such, or to the specific ] (''i.e.,'' the atypical arousal) which indicates a definite preference for animals over humans as sexual partners. Although Krafft-Ebing also coined the term ''zooerasty'' for the paraphilia of exclusive sexual attraction to animals,<ref name="deviance 391">D. Richard Laws and William T. O'Donohue: , Sexual Deviance, page 391. ], 2008. {{ISBN|978-1-59385-605-2}}.</ref> {{citation needed span|date=July 2021|text=that term has fallen out of general use}}.] | |||

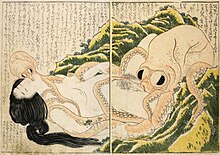

| ]<!--Katsushika is the family name so it is put first, BUT he is called by his given name-->'s (1760–1849) '']''|220x220px]] | |||

| ===Zoosexuality=== | |||

| The term ''zoosexual'' was proposed by ] in 2002<ref name="Handbookth"/> as a ''value-neutral'' term. Usage of ''zoosexual'' as a noun (in reference to a person) is synonymous with zoophile, while the adjectival form of the word – as, for instance, in the phrase "zoosexual act" – may indicate sexual activity between a human and an animal. The derivative noun "zoosexuality" is sometimes used by self-identified zoophiles in both support groups and on internet-based discussion forums to designate ] manifesting as sexual attraction to animals.<ref name="Handbookth"/> | |||

| ===Bestiality=== | |||

| The ambiguous term ], usually referring to non-procreative sex {{ref|sodomylaw}}, has sometimes been used in legal contexts to include zoosexual acts. "'''Zooerasty'''" is an older term, not in common use. In ], human/animal sex is occasionally referred to as ''farmsex'', ''dogsex'' or ''animal sex''. | |||

| Some zoophiles and researchers draw a distinction between ''zoophilia'' and ''bestiality'', using the former to describe the desire to form sexual relationships with animals, and the latter to describe the sex acts alone.<ref>{{cite web |author=Cory Silverberg |date=12 March 2010 |title=Zoophilia |url=http://sexuality.about.com/od/glossary/g/zoophilia.htm |website=Sexuality.about.com |access-date=13 May 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120321175334/http://sexuality.about.com/od/glossary/g/zoophilia.htm |archive-date=21 March 2012 |url-status=deviated}}</ref> Confusing the matter yet further, writing in 1962, William H. Masters used the term ''bestialist'' specifically in his discussion of zoosadism.{{Citation needed|reason=There is no source for this statement|date=July 2021}} | |||

| Stephanie LaFarge, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the ], and Director of Counseling at the ], writes that two groups can be distinguished: bestialists, who rape or abuse animals, and zoophiles, who form an emotional and sexual attachment to animals.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.riverfronttimes.com/1999-12-15/news/all-opposed-say-neigh/ |author=Melinda Roth |work=Riverfront Times |date=15 December 1991 |title=All Opposed, Say Neigh |access-date=24 January 2009 |archive-date=4 May 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150504031547/http://www.riverfronttimes.com/1999-12-15/news/all-opposed-say-neigh/}}</ref> ] and ] studied self-defined zoophiles via the internet and reported them as understanding the term ''zoophilia'' to involve concern for the animal's welfare, pleasure, and consent, as distinct from the self-labelled zoophiles' concept of "bestialists", whom the zoophiles in their study defined as focused on their own gratification. {{harvp|Williams|Weinberg|2003}} also quoted a British newspaper saying that ''zoophilia'' is a term used by "apologists" for ''bestiality''.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Williams CJ, Weinberg MS |title=Zoophilia in men: a study of sexual interest in animals |journal=Archives of Sexual Behavior |volume=32 |issue=6 |pages=523–35 |date=December 2003 |pmid=14574096 |doi=10.1023/A:1026085410617|s2cid=13386430 }}</ref> | |||

| Amongst zoophiles, the term "'''bestialist'''" has acquired a negative connotation implying a lower concern for animal welfare. This arises from the desire by some zoophiles to distinguish zoophilia as a fully relational outlook (sexual or otherwise), from simple "ownership with sex." Others describe themselves as zoophiles ''and'' bestialists in accordance with the dictionary definitions of the words. | |||

| {{anchor|Faunoiphilia}} | |||

| Sexual arousal from watching animals mate is known as ''faunoiphilia''.<ref>Aggrawal, Anil. . CRC Press, 2008.</ref> | |||

| In a '''non-zoophilic context''', words like "bestial" or "bestiality" are also used to signify acting or behaving savagely, animal-like, extremely viciously, or lacking in human values. (Ironically, as is often stated in literature, humans are considered far more "bestial" in this sense than animals. The classic example cited is that animals kill for food or defence, but only humans kill and torture for fun or power.) | |||

| == |

==Extent of occurrence== | ||

| ]'' ] from ]'s series, "Eight Canine Heroes of the House of Satomi", 1837 ]] | |||

| The ]s of 1948 and 1953 estimated the percentage of people in the general population of the United States who had at least one sexual interaction with animals as 8% for males and 5.1% for females (1.5% for pre-adolescents and 3.6% for post-adolescents females), and claimed it was 40–50% for the ] and even higher among individuals with lower ]al status.<ref name="deviance 391" /> Some later writers dispute the figures, noting that the study lacked a random sample in that it included a disproportionate number of prisoners, causing ]. ] has written that it is difficult to get a random sample in sexual research, but pointed out that when ], Kinsey's research successor, removed prison samples from the figures, he found the figures were not significantly changed.<ref>Richard Duberman: {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090111215816/http://www.kinseyinstitute.org/publications/duberman.html |date=11 January 2009 }}, Kinsey's Urethra ''The Nation,'' 3 November 1997, pp. 40–43. Review of ''Alfred C. Kinsey: A Public/Private Life.'' By James H. Jones.</ref>]By 1974, the farm population in the US had declined by 80 percent compared with 1940, reducing the opportunity to live with animals; Hunt's 1974 study suggests that these demographic changes led to a significant change in reported occurrences of bestiality. The percentage of males who reported sexual interactions with animals in 1974 was 4.9% (1948: 8.3%), and in females in 1974 was 1.9% (1953: 3.6%). Miletski believes this is not due to a reduction in interest but merely a reduction in opportunity.<ref>Hunt 1974, cited and re-examined by Miletski (1999)</ref> | |||

| ]'s 1973 book on ], '']'', comprised around 190 fantasies from different women; of these, 23 involve zoophilic activity.<ref>{{cite book|author=Nancy Friday|title=My Secret Garden|publisher=Simon and Schuster|edition=Revised|year=1998|isbn=978-0-671-01987-7|pages=180–185|chapter=What do women fantasize about? The Zoo|orig-year=1973|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=J9ZKmplu4agC&pg=PA180}}</ref> | |||

| The extent to which zoophilia occurs is not known with any certainty, largely because feelings which may not have been acted upon can be difficult to quantify, lack of clear divide between non-sexual zoophilia and everyday pet care, and reluctance by most zoophiles to disclose their feelings. Instead most research into zoophilia has focused on its characteristics, rather than quantifying it. | |||

| In one study, psychiatric patients were found to have a statistically significant higher prevalence rate (55 percent) of reported bestiality, both actual sexual contacts (45 percent) and sexual fantasy (30 percent) than the control groups of medical in-patients (10 percent) and psychiatric staff (15 percent).<ref name="psych">{{cite journal |pmid=1778686 |year=1991 |last1=Alvarez |first1=WA |last2=Freinhar |first2=JP |title=A prevalence study of bestiality (zoophilia) in psychiatric in-patients, medical in-patients, and psychiatric staff |volume=38 |issue=1–4 |pages=45–7 |journal=International Journal of Psychosomatics}}</ref> {{harvp|Crépault|Couture|1980}} reported that 5.3 percent of the men they surveyed had fantasized about sexual activity with an animal during heterosexual intercourse.<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1007/BF01542159 |title=Men's erotic fantasies |year=1980 |last1=Crépault |first1=Claude |last2=Couture |first2=Marcel |journal=Archives of Sexual Behavior |volume=9 |issue=6 |pages=565–81 |pmid=7458662 |s2cid=9021936}}</ref> In a 2014 study, 3% of women and 2.2% of men reported fantasies about having sex with an animal.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Joyal |first1=C. C. |last2=Cossette |first2=A. |last3=Lapierre |first3=V. |year=2014 |title=What Exactly Is an Unusual Sexual Fantasy? |journal=The Journal of Sexual Medicine |volume=12 |issue=2 |pages=328–340 |doi=10.1111/jsm.12734 |pmid=25359122 |s2cid=33785479}}</ref> A 1982 study suggested that 7.5 percent of 186 university students had interacted sexually with an animal.<ref>{{cite journal |pmid=7164870 |year=1982 |last1=Story |first1=M. D. |title=A comparison of university student experience with various sexual outlets in 1974 and 1980 |volume=17 |issue=68 |pages=737–47 |journal=Adolescence}}</ref> A 2021 review estimated zoophilic behavior occurs in 2% of the general population.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last1=Campo-Arias |first1=Adalberto |last2=Herazo |first2=Edwin |last3=Ceballos-Ospino |first3=Guillermo A. |date=March 2021 |title=Review of cases, case series and prevalence studies of zoophilia in the general population |url=http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcp/v50n1/0034-7450-rcp-50-01-34.pdf |journal=Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría |language=es |volume=50 |issue=1 |pages=34–38 |doi=10.1016/j.rcp.2019.03.003 |pmid=33648694 |s2cid=182495781 |issn=0034-7450 |archive-date=2022-02-04 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220204073102/http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcp/v50n1/0034-7450-rcp-50-01-34.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| Scientific surveys estimating the frequency of zoosexuality, as well as anecdotal evidence and informal surveys, suggest that more than 1-2% -- and perhaps as many as 8-10% -- of sexually active adults have had significant sexual experience with an animal at some point in their lives. Studies suggest that a larger number (perhaps 10-30% depending on area) have fantasized or had some form of brief encounter. Larger figures such as 40-60% for rural teenagers (living on or near livestock farms) have been cited from some earlier surveys such as the ]s, but some later writers consider these uncertain. Anecdotally, ]'s 1973 book on ] '']'' comprised around 180 women's contributions; of these, some 10% volunteered a serious interest or active participation in zoosexual activity. | |||

| ] about zoosexual acts can occur in people who do not wish to experience them in real life, and may simply reflect normal imagination and curiosity. ] zoophile tendencies may be common; the frequency of interest and sexual excitement in watching animals ] is cited as an indicator of this by Massen (1994). | |||

| == Legal status == | |||

| Zoosexual acts are illegal in many jurisdictions, while others generally outlaw the mistreatment of animals without specifically mentioning sexuality. Because it is unresolved under the law whether sexual relations with an animal are inherently "abusive" or "mistreatment", this leaves the status of zoosexuality unclear in some jurisdictions. | |||

| * Just over half of ]s explicitly outlaw sex with animals (sometimes under the term of "]"). In the 2000s, six U.S. states adopted new legislation against it: Oregon, Maine, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana. Many U.S. state laws against "sodomy" (generally in the context of male homosexuality) were repealed or struck down by the courts in ], which ruled that perceived moral disapproval on its own was an insufficient justification for banning a private act. On the other hand, the 2004 conviction of a man in Florida () demonstrated that even in states with no specific laws against zoosexual acts, animal cruelty statutes would instead be applied, and ] showed that some courts might be "desperate to avoid the plain consequences" of Lawrence and may make "narrow and strained" efforts to avoid seeing it as relevant to other consensual private acts beyond the realm of homosexuality {{ref|MuthvFrank}}. Finally, the 1999 ] case showed that when a self-confessed zoophile is assaulted and the assault is motivated by his zoophilia (ie ]), a jury can convict the assailant and a judge give a stern sentence, despite the controversial nature of the cause. | |||

| * In ], laws are determined at the state level, with all but the ] and ] explicitly outlawing it. | |||

| * In ], sex with animals is not specifically outlawed (but trading pornography showing it is, cf. ). In ], the law making it a crime (] StGB, which also outlawed homosexual acts) was removed in ]. ] before ] had no law against zoosexuality; zoosexual pornography, however, was very restricted. Certain barriers are set by the Animal Protection Law (''Tierschutzgesetz''). | |||

| * In the ], it is illegal, with of the ] reducing the sentence to a maximum of 2 years imprisonment for human penile penetration of or by an animal. | |||

| * Zoosexual acts are illegal in ] (section 160 forbidding "bestiality". The term is not defined, so it is not quite clear what it might cover.) | |||

| * Zoosexual acts are illegal in ] under a variety of sections contained in the Crimes Act 1961. Section 143, makes "beastiality" an offence, but as in Canada, the meaning of beastiality is derived from case law. There are also associated offences of indecency with an animal (section 144) and compelling an indecent act with an animal (section 142A). It is interesting to note that in the 1989 Crimes Bill considered abolition of beastiality as a criminal offence, and for it to be treated as a ] issue. In ''Police v Sheary'' (1991) 7 CRNZ 107 (HC) Fisher J considered that "he community is generally now more tolerant and understanding of unusual sexual practices that do not harm others." | |||

| * In some countries laws existed against single males living with female animals. For example, an old ]vian law prohibited single males from having a female ] (]). | |||

| == Zoophiles == | |||

| === Zoophilia as a lifestyle === | |||

| Separate from those whose interest is curiosity, pornography, or sexual novelty, are those for whom zoophilia might be called a lifestyle or orientation. A commonly reported starting age is at ], around 9 - 11, and this seems consistent for both males and females. Kinsey found that the most frequent incidence of human/animal intercourse was more than eight times a week, for the under-15 years age group. Those who discover an interest at an older age often trace it back to nascent form during this period or earlier. As with human attraction, zoophiles may be attracted only to particular species, appearances, personalities or individuals, and both these and other aspects of their feelings vary over time. | |||

| Zoophiles tend to perceive differences between animals and human beings as less significant than others do. They often view animals as having positive traits (e.g. honesty) that humans often lack, and to feel that society's understanding of non-human sexuality is misinformed. Although some feel guilty about their feelings and view them as a problem (also see '']''), others do not feel a need to be constrained by traditional standards in their private relationships. | |||

| The biggest difficulties many zoophiles report are the inability to be accepted or open about their animal relationships and feelings with friends and family, and the fear of harm, rejection or loss of companions if it became known (see '']'' and '']'', sometimes humorously referred to as "the stable"). Other major issues are hidden loneliness and isolation (due to lack of contact with others who share this attraction or a belief they are alone), and the impact of repeated deaths of animals they consider lifelong soulmates (most species have far shorter lifespans than humans and they cannot openly grieve or talk about feelings of loss). Some of these concerns are qualitatively similar to historical ] that have been legal or illegal at different times in history. Zoophiles do not usually cite internal conflicts over ] as their major issue, perhaps because zoophilia, although condemned by many religions, is not a major focus of their teachings. | |||

| Zoophilic sexual relationships vary, and may be based upon variations of human-style relationships (eg ]), animal-style relationships (each make own sexual choices), physical intimacy (touch, mutual grooming, closeness), or other combinations. | |||

| Zoophiles may or may not have human partners and families. Some zoophiles have an affinity or attraction to animals which is secondary to human attraction; others have a primary bond with an animal. In some cases human family or friends are aware of the relationship with the animal and its nature, in others it is hidden. This can sometimes give rise to issues of ] (as a result of divided loyalties and concealment) or ] within human relationships . In addition, zoophiles sometimes enter human relationships due to growing up within traditional expectations, or to deflect suspicions of zoophilia, and yet others may choose looser forms of human relationship as companions or housemates, live alone, or choose other zoophiles to live with. | |||

| === Non-sexual zoophilia === | |||

| Although the term is often used to refer to sexual interest in animals, zoophilia is not necessarily sexual in nature. In ] and ] it is sometimes used without regard to sexual implications. The first definition listed for the word on is "Affection or affinity for animals". Other definitions are: | |||

| * "Erotic attraction to or sexual contact with animals" | |||

| * "Attraction to or affinity for animals" | |||

| * "An erotic fixation on animals that may result in sexual excitement through real or fancied contact" | |||

| The common feature of "zoophilia" is some form of affective bond to animals beyond the usual, whether emotional or sexual in nature. Non-sexual zoophilia is generally accepted in society, and although sometimes ridiculed, it is usually respected or tolerated. Examples of non-sexual zoophilia can be found on animal memorial pages such as memorial and support site, or by ] "pet memorials". | |||

| === Zoophiles and other groups === | |||

| Zoophiles are often confused with '']'' or '']s (or "weres")'', that is, people with an interest in ], or people who believe they share some kind of inner connection with animals (spiritual, emotional or otherwise). While the membership of all three groups probably overlap in part, it is untrue to say that all furs or therians have a sexual interest in animals (subconscious or otherwise). Many furs find anthropomorphic adult art erotic and enjoy the companionship of animals, but have no wish to extend their interest beyond an affinity or emotional bond to sexual activity. Those who consider themselves both zoophiles and furries, often call themselves ''zoo-furs'' or ''fuzzies''. The size of this group is not known, although an oft-cited figure is 5% of furries, which is not dissimilar to typical estimates of the percentage within the population generally. Expressions of ] such as ]ing, are usually considered a form of costuming, rather than an expression of zoosexual interest and are usually legal. | |||

| Finally, zoophilia is not related to sexual ] (also known as "Petplay") or ], where one person may acts like a dog, pony, horse, or other animal, while a sexual partner acts as a rider, trainer, caretaker, or breeding partner. These activities are ] whose principal theme is the voluntary or involuntary reduction or transformation of a human being to animal status, and focus on the altered mind-space created. They have no implicit connection to, nor motive in common with, zoophilia. They are instead more usually associated with ]. Zoosexual activity is not part of BDSM for most people, and would usually be considered extreme, or ]. | |||

| ==Perspectives on zoophilia== | ==Perspectives on zoophilia== | ||

| === |

=== Research perspectives === | ||

| Zoophilia has been discussed by several sciences: ] (the study of the human ]), ] (a relatively new discipline primarily studying ]), ] (the study of ]), and ] (the study of human–animal interactions and bonds). | |||

| In the fifth edition of the '']'' (DSM-5), zoophilia is placed in the classification "other specified paraphilic disorder"<ref name="DSM 5">{{cite book | title = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition | chapter = Other Specified Paraphilic Disorder, 302.89 (F65.89) | editor = American Psychiatric Association | year = 2013 | publisher = American Psychiatric Publishing | page = 705}}</ref> ("]s not otherwise specified" in the DSM-III and IV<ref name=DSM> | |||

| ] (APA, 1987) stated that sexual contact with animals is almost never a clinically significant problem by itself (Cerrone, 1991), and therefore both this and the later ] (APA, 1994) subsumed it under the residual classification "] not otherwise specified". | |||

| {{cite book |title= Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV | publisher = ] | location=Washington, DC |year=2000 |isbn=978-0-89042-025-6 |oclc=43483668 | title-link = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders }} | |||

| </ref><ref name = Milner2008> | |||

| {{cite book | editor1 = Laws, D. R. | editor2 = O'Donohue, W. T. | last = Milner | first = J. S. | author2 = Dopke, C. A. | title = Sexual Deviance, Second Edition: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment | publisher = ] | location = New York | year = 2008 | pages = |isbn=978-1-59385-605-2 |oclc=152580827| chapter = Paraphilia Not Otherwise Specified: Psychopathology and theory}} | |||

| </ref><ref name = Lovemaps> | |||

| {{cite book |author=Money, John |author-link = John Money |title=Lovemaps: Clinical Concepts of Sexual/Erotic Health and Pathology, Paraphilia, and Gender Transposition in Childhood, Adolescence, and Maturity |publisher=] |location=Buffalo, N.Y |year=1988 |isbn=978-0-87975-456-3 |oclc=19340917 }} | |||

| </ref><ref name = Seto2000> | |||

| {{cite book |editor1 = Hersen, M. |editor2 = Van Hasselt, V. B. | title = Aggression and violence: an introductory text |publisher= ] |location=Boston |year=2000 |pages= 198–213 |isbn=978-0-205-26721-7 |oclc=41380492 | last = Seto| first = MC| author2 = Barbaree HE | chapter = Paraphilias}} | |||

| </ref>). The ] takes the same position, listing a sexual preference for animals in its ] ] as "other disorder of sexual preference".<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/ |title=International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10, F65.8 Other disorders of sexual preference |website=Who.int |access-date=13 May 2012}}</ref> In the DSM-5, it rises to the level of a diagnosable disorder only when accompanied by distress or interference with normal functioning.<ref name="DSM 5" /><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Miletski |first1=H. |s2cid=146150162 |year=2015| title=Zoophilia – Implications for Therapy |journal=Journal of Sex Education and Therapy| volume=26 |issue=2| pages=85–86 |doi=10.1080/01614576.2001.11074387}}</ref> | |||

| Zoophilia may be covered to some degree by other fields such as ethics, philosophy, law, ] and ]. It may also be touched upon by sociology which looks both at zoosadism in examining patterns and issues related to ] and at non-sexual zoophilia in examining the role of animals as emotional support and companionship in human lives, and may fall within the scope of ] if it becomes necessary to consider its significance in a clinical context. The ''Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine'' (Vol. 18, February 2011) states that sexual contact with animals is almost never a clinically significant problem by itself;<ref name="Aggrawal">{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/j.jflm.2011.01.004 |title=A new classification of zoophilia |year=2011 |last1=Aggrawal |first1=Anil |journal=Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine |volume=18 |issue=2 |pages=73–8 |pmid=21315301}}</ref> it also states that there are several kinds of zoophiles:<ref name="Aggrawal"/> | |||

| The first detailed studies of zoophilia date from prior to 1910. Peer reviewed research into zoophilia in its own right has happened since around 1960. There have been several significant modern studies, from Masters (1962) to Beetz (2002), but each of them has drawn and agreed on several broad conclusions: | |||

| # The critical aspect to study was emotion, relationship, and motive, it is important not to just assess or judge the sexual act alone in isolation, or as "an act", without looking deeper. (Masters, Miletski, Beetz) | |||

| # Zoophiles' emotions and care to animals can be real, relational, authentic and (within animals' abilities) reciprocal, and not just a substitute or means of expression. (Masters, Miletski, Weinberg, Beetz) | |||

| # Most zoophiles have (or have also had) long term human relationships as well or at the same time as zoosexual ones. (Masters, Beetz) | |||

| # Society in general at present is considerably misinformed about zoophilia, its stereotypes, and its meaning (Masters, Miletski, Weinberg, Beetz) | |||

| # Contrary to popular belief, there is in fact significant popular or "latent" interest in zoophilia, either in fantasy, animal mating, or reality (Nancy Friday, Massen, Masters) | |||

| # The distinction between zoophilia and zoosadism is a critical one, and highlighted by each of these studies. | |||

| # Masters (1962), Miletski (1999) and Weinberg (2003) each comment significantly on the social harm caused by these, and other common misunderstandings: "This destroy the lives of many citizens". | |||

| {{div col|colwidth=20em}} | |||

| At times, research has been cited based upon the degree of zoosexual or zoosadistic related history within populations of juvenile and other persistent offenders, prison populations with records of violence, and people with prior psychological issues. Such studies are not viewed professionally as valid means to research or profile zoophilia, as the results would be based upon populations pre-selected as knowingly having high proportions of criminal records, abusive tendencies and/or psychological issues. This approach (used in some older research and quoted to demonstrate ]) is considered discredited and unrepresentative by researchers. | |||

| *Human-animal role-players | |||

| *Romantic zoophiles | |||

| *Zoophilic fantasizers | |||

| *Tactile zoophiles | |||

| *Fetishistic zoophiles | |||

| *Sadistic bestials | |||

| *Opportunistic zoophiles | |||

| *Regular zoophiles | |||

| *Exclusive zoophiles | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| ''Romantic zoophiles'', ''zoophilic fantasizers'', and ''regular zoophiles'' are the most common, while ''sadistic bestials'' and ''opportunistic zoophiles'' are the least common.<ref name="Aggrawal"/> | |||

| An example of such a statistic is a statement that "96% of people who commit bestiality will go on to commit crimes against people" quoted by ] , which is sourced from a study of such a population <!--(24 out of the sample of 381 criminals had zoosexual experience although the survey did not explore the motive or intent)-->. When read in full however, the study also includes the following caution regarding interpretation of their results: ''"It is difficult to assess 'normality' in a study where all 381 participants were adjudicated juvenile offenders living in state facilities ... It is possible that among other populations ... sex acts with animals might be performed out of love, the need for consolation, or other motivations. In these and other populations, there might not be any link whatsoever to offenses against humans."'' This qualification is not mentioned by PETA. | |||

| Zoophilia may reflect childhood experimentation, sexual abuse or lack of other avenues of sexual expression. Exclusive desire for animals rather than humans is considered a rare paraphilia, and they often have other paraphilias<ref name="LawsO'Donohue2008">{{cite book |author1=D. Richard Laws |author2=William T. O'Donohue |title=Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yIXG9FuqbaIC&q=zoophilia+rare&pg=PA391 |date=January 2008 |publisher=Guilford Press |isbn=978-1-59385-605-2 |page=391}}</ref> with which they present. Zoophiles will not usually seek help for their condition, and so do not come to the attention of psychiatrists for zoophilia itself.<ref name="Roukema2008">{{cite book |author=Richard W. Roukema |title=What Every Patient, Family, Friend, and Caregiver Needs to Know About Psychiatry, Second Edition |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=t7Mg3iuc9ygC&q=zoophilia+other+paraphilias&pg=PA133 |date=13 August 2008 |publisher=American Psychiatric Pub |isbn=978-1-58562-750-9 |page=133}}</ref> | |||

| === Religious perspectives=== | |||

| Most organized religions take a critical or sometimes condemnatory view of zoophilia or zoosexuality, with some variation and exceptions. | |||

| * Passages in ] 18:23 ("And you shall not lie with any beast and defile yourself with it, neither shall any woman give herself to a beast to lie with it: it is a perversion." RSV) and 20:15-16 ("If a man lies with a beast, he shall be put to death; and you shall kill the beast. If a woman approaches any beast and lies with it, you shall kill the woman and the beast; they shall be put to death, their blood is upon them." RSV) are cited by ], ], and ] theologians as categorical denunciation of zoosexuality. Some theologians (especially Christian) extend this, to consider ]ful thoughts for animal as a sin. Alternatively, many Christians and some non-Orthodox Jews do not regard the full Levitical laws as binding upon them, and may consider them irrelevant. Some zoophiles take this injunction to indicate that sex with animals in the ] is forbidden, but that other positions are not specifically mentioned nor apparently against the divine will. | |||

| * Views of its seriousness in ] seem to cover a wide spectrum. This may be because it is not explicitly mentioned or prohibited in the ], or because sex and sexuality were not treated as ] in Muslim society to the same degree as in Christianity. Some sources claim that sex with animals is abhorrent, others state that while condemned, it is treated with "relative indulgence" and in a similar category to ] and ]ism (Bouhdiba: Sexuality in Islam, Ch.4 ). A book "]", cited on the internet, which quotes the ] approving of sex with animals under certain conditions, is unconfirmed and possibly a forgery. | |||

| * There are several references in ] scriptures to religious figures engaging in sexual activity with animals (e.g. the god ] lusting after and having sex with a bear, a human-like sage being born to a deer mother), and actual ] rituals involving zoosexual activity (see ]), as well as explicit depictions of people having sex with animals included amongst the thousands of sculptures of "Life events" on the exterior of the ] at ]. Orthodox Hindu doctrine holds that sex should be restricted to married couples, thereby forbidding zoosexual acts. A greater punishment is attached to sexual relations with a sacred cow than with other animals. However, the ] sect of Hinduism makes use of ritual sexual practices, which could include sexual contact with animals. | |||

| * ] addresses sexual conduct primarily in terms of what brings harm to oneself or to others, and the admonition against sexual misconduct is generally interpreted in modern times to prohibit zoosexual acts, as well as ], ], ], or ]. Zoosexuality (as well as various other sexual activity) is expressly forbidden for Buddhist monks and nuns. | |||

| * In the ] sexual acts involving children and/or animals are universally condemned, as are those in which a human who is too naive to understand is involved. The Satanic Bible states (p.66) that animals and children are treated as sacred as they are regarded as the most natural expression of life. | |||

| The first detailed studies of zoophilia date prior to 1910. Peer-reviewed research into zoophilia in its own right started around 1960. However, a number of the most oft-quoted studies, such as Miletski, were not published in ] journals. There have been several significant modern books, from psychologists William H. Masters (1962) to Andrea Beetz (2002);<ref name="Beetz2002">Beetz 2002, section 5.2.4 – 5.2.7.</ref> their research arrived at the following conclusions: | |||

| ===Animal studies perspectives=== | |||

| ''(Main article: ])'' | |||

| *Most zoophiles have (or have also had) long term human relationships as well or at the same time as bestial ones, and bestial partners are usually dogs and/or horses.<ref name="Beetz2002"/><ref name="Aggrawal2008">{{cite book|author=Anil Aggrawal|title=Forensic and Medico-legal Aspects of Sexual Crimes and Unusual Sexual Practices|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uNkNhPZQprcC&q=zoophilia+most+common+animal&pg=PA257|access-date=13 May 2012|date=22 December 2008|publisher=CRC Press|isbn=978-1-4200-4309-9|page=257}}</ref> | |||

| The common concept of animals as heterosexual and only interested in their own species, is seen as scientifically inaccurate by researchers into animal behavior. Animals are in the main, considered as sexual opportunists by science, rather than sexually naive. ] such as ] who study animal behavior, as well as formal studies, have consistently documented significant homosexuality in a wide range of animals, apparently freely chosen or in the presence of the opposite gender, as well as homosexual animal couples, homosexual raising of young, and cross-species sexual advances. Peter Singer reports of one such incident witnessed by ] (a notable ethologist considered by many the world's foremost authority on ]): | |||

| *Zoophiles' emotions and care for animals can be real, relational, authentic and (within animals' abilities) reciprocal{{how|date=January 2025}}, and not just a substitute or means of expression.<ref>(Masters, Miletski, Weinberg, Beetz)</ref> Beetz believes zoophilia is not an inclination which is chosen.<ref name="Beetz2002"/> | |||

| :''"While walking through the camp with Galdikas, my informant was suddenly seized by a large male orangutan, his intentions made obvious by his erect penis. Fighting off so powerful an animal was not an option, but Galdikas called to her companion not to be concerned, because the orangutan would not harm her, and adding, as further reassurance, that "they have a very small penis." As it happened, the orangutan lost interest before penetration took place, but the aspect of the story that struck me most forcefully was that in the eyes of someone who has lived much of her life with orangutans, to be seen by one of them as an object of sexual interest is not a cause for shock or horror. The potential violence of the orangutan's come-on may have been disturbing, but the fact that it was an orangutan making the advances was not."'' | |||

| * Society in general is considerably misinformed about zoophilia, its stereotypes, and its meaning.{{Clarify|date=November 2024}}<ref name="Beetz2002"/> The distinction between zoophilia and zoosadism is a critical one to these researchers, and is highlighted by each of these studies. Masters (1962), Miletski (1999) and Weinberg (2003) each comment significantly on the social harm caused by misunderstandings regarding zoophilia: "This destroy the lives of many citizens".{{Clarify|date=November 2024}}<ref name="Beetz2002"/> | |||

| More recently, research has engaged three further directions: the speculation that at least some animals seem to enjoy a zoophilic relationship assuming ] is not present, and can form an affectionate bond.<ref>Masters, 1962.</ref> | |||

| === Animal rights and welfare concerns=== | |||

| Beetz described the phenomenon of zoophilia/bestiality as being somewhere between crime, paraphilia, and love, although she says that most research has been based on ] reports, so the cases have frequently involved violence and psychiatric illness. She says only a few recent studies have taken data from volunteers in the community.<ref>. Scie-SocialCareOnline.org.uk. {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101115133416/http://www.scie-socialcareonline.org.uk/profile.asp?guid=fac3acab-5377-4f9a-a9f0-007248ee2e43 |date=15 November 2010 }}</ref> As with all volunteer surveys and sexual ones in particular, these studies have a potential for ] bias.<ref name="Slade2001">{{cite book|author=Joseph W. Slade|title=Pornography and Sexual Representation: A Reference Guide|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Opv9nz2M5c0C&q=%22volunteer+selection%22+sex&pg=PA980|year=2001|publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group|isbn=978-0-313-31521-3|page=980}}</ref> | |||

| One of the primary critiques of zoophilia is the argument that zoosexuality is harmful to animals. Some state this categorically; that any sexual activity is necessarily abuse. Critics also point to examples in which animals were clearly abused, having been tied up, assaulted, or injured. Defenders of zoophilia argue that animal abuse is neither typical of nor commonplace within zoophilia, and that just as sexual activity with humans can be both abusive and not, so can sexual activity with animals. | |||

| Medical research suggests that some zoophiles only become aroused by a specific species (such as horses), some zoophiles become aroused by multiple species (which may or may not include humans), and some zoophiles are not attracted to humans at all.<ref name="earls" /><ref>{{cite journal |pmid=15895645 |year=2005 |last1=Bhatia |first1=MS |last2=Srivastava |first2=S |last3=Sharma |first3=S |s2cid=5744962 |title=1. An uncommon case of zoophilia: A case report |volume=45 |issue=2 |pages=174–75 |journal=Medicine, Science, and the Law |doi=10.1258/rsmmsl.45.2.174}}</ref> | |||

| ] Ph.D in her book on sex and violence with animals (2002) reports: "in most references to bestiality, violence towards the animal is automatically implied. That sexual approaches to animals may not need force or violence but rather, sensitivity, or knowledge of animal behavior, is rarely taken into consideration." | |||

| In comment on ]'s article , which controversially argued that zoosexuality need not be abusive and if so loving relationships could form, Ingrid Newkirk, then president of the ] ] group ], added this endorsement: "If a girl gets sexual pleasure from riding a horse, does the horse suffer? If not, who cares? If you ] your dog and he or she thinks it's great, is it wrong? We believe all exploitation and abuse is wrong. If it isn't exploitation and abuse, it may not be wrong." | |||

| (A few years later, Newkirk wrote to the editor of the Canada Free Press in response to a , making clear that she was strongly opposed to any exploitation, and all sexual activity, with animals. This was necessary since some had sought to interpret her former statement as condoning zoosexuality. Accordingly, the response was a clarification of her position regarding zoosexual acts, rather than a different response ''per se'' to Singer's actual philosophical point, namely "if it isn't exploitation and abuse ") | |||

| ] (1990, cited by Rosenbauer 1997) coined the separate term ''"]"'' for those who derive pleasure from inflicting pain on an animal, sometimes with a sexual component. Some extreme examples of zoosadism include ], the sexual enjoyment of killing animals (similar to "]" in humans), sexual penetration of fowl such as hens (fatal in itself) and strangling at orgasm, mutilation, sexual assault with objects (including screwdrivers and knives), interspecies ], and ] on immature animals such as puppies. Some horse-ripping incidents have a sexual connotation (Schedel-Stupperich, 2001). The link between sadistic sexual acts with animals and sadistic practices with humans or lust murders has been heavily researched. Some murderers tortured animals in their childhood and also sexual relations with animals occurred. Ressler et al. (1986) found that 8 of their sample of 36 sexual murderers showed an interest in zoosexual acts. (Main article: '']'') | |||

| Sexology information sites (if sufficiently detailed) are usually careful to distinguish zoosadism from zoophilia: and . | |||

| ===Historical and cultural perspectives=== | ===Historical and cultural perspectives=== | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|Historical and cultural perspectives on zoophilia}} | ||

| ]. This German illustration shows Jews performing bestiality on a '']'', while Satan watches.]] | |||

| == Health and safety == | |||

| Instances of zoophilia and bestiality have been found in the Bible,<ref name="aggrawal_2009_16_3">{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/j.jflm.2008.07.006 |title=References to the paraphilias and sexual crimes in the Bible |year=2009 |last1=Aggrawal |first1=Anil |journal=Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine |volume=16 |issue=3 |pages=109–14 |pmid=19239958}}</ref> but the earliest depictions of bestiality have been found in a cave painting from at least 8000 BC in the Northern Italian ] a man is shown about to penetrate an animal. Raymond Christinger interprets the cave painting as a show of power of a tribal chief,<ref>, Link to web page and photograph, archaeometry.org</ref> it is unknown if this practice was then more acceptable, and if the scene depicted was usual or unusual or whether it was symbolic or imaginary.<ref name="Bevan2006">{{cite book|author=Lynne Bevan|title=Worshippers and warriors: reconstructing gender and gender relations in the prehistoric rock art of Naquane National Park, Valcamonica, Brecia, northern Italy|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WzxmAAAAMAAJ&q=Coren+del+Valento+animal|year=2006|publisher=Archaeopress|isbn=978-1-84171-920-7}}</ref> According to the Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art, the penetrating man seems to be waving cheerfully with his hand at the same time. ] of the same time period seem to have spent time depicting the practice, but this may be because they found the idea amusing.<ref name="Bahn1998">{{cite book|author=Paul G. Bahn|author-link=Paul Bahn|title=The Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xwm_D1u_UTsC&q=%22prehistoric+art%22+bestiality&pg=PA188|year=1998|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-45473-5|page=188}}</ref> The anthropologist Dr "''Jacobus X"'',{{efn|name=Note02|Professor Marc Epprecht states that authors such as ''Jacobus X'' do not deserve respect because their methodology is based on hearsay, and was designed for voyeuristic titillation of the reader.<ref>{{cite journal|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dJdErRqoBeQC&q=%22Jacobus+X%22+taboos&pg=PA193|title="Bisexuality" and the politics of normal in African Ethnography|journal= Anthropologica|volume=48|pages=187–201|number=2|year=2006|author=Marc Epprecht|jstor=25605310|doi=10.2307/25605310}}</ref>}} said that the cave paintings occurred "before any known taboos against sex with animals existed".<ref>''Abuses Aberrations and Crimes of the Genital Sense'', 1901.</ref> William H. Masters claimed that "since pre-historic man is ] it goes without saying that we know little of his sexual behavior";<ref>Masters, Robert E. L., ''Forbidden Sexual Behavior and Morality'', p. 5.</ref> depictions in cave paintings may only show the artist's subjective preoccupations or thoughts.{{citation needed|date=June 2023}} | |||

| ], ], and ] claimed the Egyptians engaged in ritual congress with goats.<ref name="BulloughBullough1994">{{cite book|author1=Vern L. Bullough|author2=Bonnie Bullough|title=Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=y5HFtMkmFMYC&q=bestiality+%22ancient+egypt%22+religious&pg=PA61 |date=1 January 1994|publisher=Taylor & Francis|isbn=978-0-8240-7972-7|page=61}}</ref> Such claims about other cultures do not necessarily reflect anything about which the author had evidence, but may be a form of propaganda or ], similar to ].{{citation needed|date=March 2016}} | |||

| Humans and animals cannot make each other pregnant, but infections due to improper cleaning could be an issue for either party. Most diseases are specific to particular species and cannot be transmitted sexually, so humans and animals cannot catch many diseases from zoosexual acts. However, a few uncommon but treatable ] (known as ]) such as ] can be transferred. ] is fragile and only lives in primates (humans, apes and monkeys) and is not believed to survive long in other species. Animals' and humans' bodily fluids are not incompatible, but allergic reactions can sometimes (rarely) occur. | |||

| Several cultures built temples (], India) or other structures (], ], Sweden) with zoophilic carvings on the exterior, however at ], these depictions are not on the interior, perhaps depicting that these are things that belong to the profane world rather than the spiritual world, and thus are to be left outside.{{citation needed|date=March 2016}} | |||

| In terms of physical compatibility and injury, many medium/large domesticated species appear to be physically compatible with humans. The main non-deliberate physical risks are of injury, either through ignorance of physical differences, forcefulness, or, for female animals, excessive friction or infection. Humans may also be at substantial physical risk and seriously harmed by sexual activity with animals. Larger animals may have the strength and defensive attributes (e.g. hooves, teeth) to injure a human, either in rejecting physical or sexual contact, or in the course of sexual arousal. For example, the penis of a sexually aroused dog has a broad bulb at the base which can cause injury if forcibly pulled from a body orifice, equines can thrust suddenly and "flare", and many animals bite as part of sexual excitement and foreplay. In ], a man died in ], ] after being ] by a stallion. ("The prosecutor's office says no animal cruelty charges were filed because there was no evidence of injury to the horses.") | |||

| In the Church-oriented culture of the ], zoophilic activity was met with execution, typically burning, and death to the animals involved either the same way or by hanging, as "both a violation of ] and a degradation of man as a spiritual being rather than one that is purely animal and carnal".<ref>Masters (1962)</ref> Some witches were accused of having congress with the devil in the form of an animal. As with all accusations and confessions extracted under torture in the ], their validity cannot be ascertained.<ref name="BulloughBullough1994"/> | |||

| == Arguments about zoophilia or zoosexuality == | |||

| ===Religious perspectives=== | |||

| Platonic love for animals is usually viewed positively, but most people express concern or disapproval of sexual interest, sometimes very strongly. Criticisms come from a variety of sources, including moral, ethical, psychological, and social arguments. They include: | |||

| Passages in ] (Lev 18:23: "And you shall not lie with any beast and defile yourself with it, neither shall any woman give herself to a beast to lie with it: it is a perversion." RSV) and 20:15–16 ("If a man lies with a beast, he shall be put to death; and you shall kill the beast. If a woman approaches any beast and lies with it, you shall kill the woman and the beast; they shall be put to death, their blood is upon them." RSV) are cited by Jewish, Christian, and Muslim theologians as categorical denunciation of bestiality. However, the teachings of the ] have been interpreted by some as not expressly forbidding bestiality.<ref name="Plummer">{{cite conference |last=Plummer |first=Keith |title=To beast or not to beast: does the law of Christ forbid zoophilia? |year=2001 |url=http://place.asburyseminary.edu/trenpapers/892 |conference=53rd National Conference of the Evangelical Theological Society |location=Colorado Springs, CO}}</ref> | |||

| In Part II of his '']'', medieval philosopher ] ranked various "unnatural vices" (sex acts resulting in "venereal pleasure" rather than procreation) by degrees of sinfulness, concluding that "the most grievous is the sin of bestiality".<ref> Aquinas on Unnatural Sex</ref> Some Christian theologians extend ]'s view that ] to imply that thoughts of committing bestial acts are likewise sinful. | |||

| * "Sexual activity between species is unnatural." | |||

| * "Animals are not sentient, and therefore unable to consent." (similar to arguments against sex with human minors) | |||

| * "Animals are incapable of relating to or forming relationships with humans." | |||

| * "Zoosexuality is simply for those unable/unwilling to find human partners." | |||

| * "Sexual acts with animals by humans constitute physical abuse." | |||

| * "Zoosexuality is 'profoundly disturbed behaviour.'" (cf. the UK ] review on sexual offences, 2002) | |||

| * "It offends human dignity or is forbidden by religious law." | |||

| * "Animals mate for no purpose other than to produce young." | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Defenders of zoophilia or zoosexuality counterargue that: | |||

| There are a few references in ] temples to figures engaging in symbolic sexual activity with animals such as explicit depictions of people having sex with animals included amongst the thousands of sculptures of "Life events" on the exterior of the ] at ]. The depictions are largely symbolic depictions of the sexualization of some animals and are not meant to be taken literally.<ref>Swami Satya Prakash Saraswati, ''The Critical and Cultural Study of the Shatapatha Brahmana'', p. 415.</ref> According to the Hindu tradition of erotic painting and sculpture, having sex with an animal is believed to be actually a human having sex with a god incarnated in the form of an animal.<ref name="PodberscekBeetz2005">{{cite book|first1=Anthony L. |last1=Podberscek |first2=Andrea M. |last2=Beetz |title=Bestiality and Zoophilia: Sexual Relations with Animals |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Z-GbOvrbniQC&pg=PT12 |access-date=4 January 2013 |date=1 September 2005 |publisher=Berg |isbn=978-0-85785-222-9 |page=12}}</ref> However, in some Hindu scriptures, such as the '']'' and the '']'', having sex with animals, especially the cow, leads one to ], where one is tormented by having one's body rubbed on trees with razor-sharp thorns.<ref name = "mani">{{cite book|author = Mani, Vettam|title = Puranic Encyclopaedia: A Comprehensive Dictionary With Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature|url = https://archive.org/details/puranicencyclopa00maniuoft|publisher = Motilal Banarsidass|year = 1975|location = Delhi|isbn = 978-0-8426-0822-0|oclc=2198347|pages = }}</ref> Similarly, the ] in verse 11.173 also condemns the act of bestiality and prescribes punishments for it: <blockquote>A man who has had sexual intercourse with nonhuman females, or with a menstruating woman,—and he who has discharged his semen in a place other than the female organ, or in water,—should perform the ‘Sāntapana Kṛcchra.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://gyaandweep.com/manusmriti/11/ | title=Gyaandweep | Manu Smriti , Adhyaya - 11 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.academia.edu/31478379 | title=Manu Smriti Sanskrit Text with English Translation | last1=Ganth | first1=Srimani }}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| * "'Natural' is debatable, and not necessarily relevant." | |||

| * "Animals are capable of sexual consent - and even initiation - in their own way." | |||

| * "Animals do form mutual relationships with humans." | |||

| * "Many zoophiles appear to have human partners and relationships; many others simply do not have a ] to humans." | |||

| * "It is a misperception that zoosexual activity need necessarily be inherently harmful/abusive. Usually it needs only sensitivity, mutuality, and understanding of everyday animal behavior." | |||

| * "The psychological profession consensus does not consider it intrinsically pathological." | |||

| * "Academic and clinical research consistently tends to substantiate rather than deny zoophiles' claims." | |||

| * "Perspectives on human dignity and religious viewpoints differ and are personal; many individuals do not consider them relevant." | |||

| * "Both male and female domestic animals of several species can experience the physical sensation of ], and can strongly solicit and demonstrate appreciation for it in their body language, similarly to humans." | |||

| == Legal status == | |||

| They also assert that some of these arguments rely on double standards, such as expecting informed consent from animals for sexual activity (and not accepting consent given in their own manner), but not for surgical procedures including aesthetic mutilation and castration, potentially lethal experimentation and other hazardous activities, euthanasia, and slaughter. Likewise, if animals cannot give consent, then it follows that they must not have sex with each other (amongst themselves). ]''] | |||

| <!-- PLEASE DO NOT ADD THE IMAGE Legality of bestiality by country.png TO THIS ARTICLE. tHE IMAGE IS CONSIDERED IMPROPERLY SOURCED/VERIFIED AND WILL BE REMOVED. IF YOU WISH TO DISCUSS THIS MATTER, PLEASE USE THE TALK PAGE. --> | |||

| {{Sex and the Law}} | |||

| In many jurisdictions, all acts of bestiality are prohibited; others outlaw only the mistreatment of animals, without specific mention of sexual activity. In the United Kingdom, ] (also known as the Extreme Pornography Act) outlaws images of a person performing or appearing to perform an act of intercourse or oral sex with another animal (whether dead or alive).<ref name=opsisect63>{{cite web|url=http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2008/4/section/63|work=Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008|title=Section 63 – Possession of extreme pornographic images|year=2008}}</ref> Despite the ]'s explanatory note on extreme images saying "It is not a question of the intentions of those who produced the image. Nor is it a question of the sexual arousal of the defendant",<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cps.gov.uk/legal/d_to_g/extreme_pornography/ |title=Extreme Pornography |publisher=Crown Prosecution Service |access-date=23 September 2015}}</ref> "it could be argued that a person might possess such an image for the purposes of satire, political commentary or simple grossness", according to '']''.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Jackman |first1=Myles |author-link=Myles Jackman |date=21 September 2015 |title=Is it illegal to have sex with a dead pig? Here's what the law says about the allegations surrounding David Cameron's biography |url=https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/is-it-illegal-to-have-sex-with-a-dead-pig-heres-what-the-law-says-about-the-allegations-surrounding-10510743.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20230123023727/https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/is-it-illegal-to-have-sex-with-a-dead-pig-heres-what-the-law-says-about-the-allegations-surrounding-10510743.html |archive-date=23 January 2023 |url-access=subscription |access-date=23 January 2023 |newspaper=]}}{{cbignore}}</ref> | |||

| Many laws banning sex with non-human animals have been made recently, such as in the United States (]<ref name="Newhampshire">{{cite news |title=New Hampshire HB1547 – 2016 – Regular Session |url=http://legiscan.com/NH/text/HB1547/id/1286995 |access-date=17 April 2017 |website=Legiscan.com}}</ref> and ]<ref name="Ohio">{{cite web |title=Ohio SB195 – 2015–2016 – 131st General Assembly |url=http://legiscan.com/OH/text/SB195/2015 |access-date=16 November 2017 |website=Legiscan.com}}</ref>), Germany,<ref>{{cite web |url=https://dejure.org/gesetze/TierSchG/3.html|title=§ 3 TierSchG |website=Dejure.org|access-date=20 October 2018}}</ref> Sweden,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.webpronews.com/sweden-joins-an-increasing-number-of-european-countries-that-ban-bestiality-2013-06|title=Sweden Joins An Increasing Number of European Countries That Ban Bestiality|website=Webpronews.com|date=13 June 2013|access-date=16 November 2017}}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.mbl.is/monitor/frettir/2014/04/07/stundar_kynlif_med_hundinum_sinum/|title=Stundar kynlíf með hundinum sínum|website=www.mbl.is}}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://politik.tv2.dk/2015-04-21-flertal-for-lovaendring-nu-bliver-sex-med-dyr-ulovligt|title=Flertal for lovændring: Nu bliver sex med dyr ulovligt|date=21 April 2015|access-date=20 October 2018}}</ref> ],<ref> {{dead link|date=October 2018}}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.elpais.cr/2016/03/09/diputados-aclaran-alcances-y-limites-de-la-nueva-ley-de-bienestar-animal/|title=Diputados aclaran alcances y límites de la nueva Ley de Bienestar Animal |website=Elpais.cr|date=10 March 2016|access-date=16 November 2017}}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.derechoteca.com/gacetabolivia/ley-no-700-del-01-de-junio-de-2015/ |title=LEY No 700 del 01 de Junio de 2015 |website=Derechoteca.com |access-date=16 November 2017}}</ref> and ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://gt.transdoc.com/articulos/archivos-leyes/Ley-de-Proteccin-y-Bienestar-Animal/62680 |title=Ley de Protección y Bienestar Animal |website=Transdoc Archivos Leyes |language=es |access-date=16 November 2017 |archive-date=2 December 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201202194637/https://gt.transdoc.com/articulos/archivos-leyes/Ley-de-Proteccin-y-Bienestar-Animal/62680}}</ref> The number of jurisdictions around the world banning it has grown in the 2000s and 2010s. | |||

| People's views appear to depend significantly upon the nature of their interest and nature of exposure to the subject. ''People who have been exposed to zoosadism'', who are unsympathetic to ] in general, or who know little about zoophilia, often regard it as an extreme form of ] and/or indicative of serious psychosexual issues. ''Mental health professionals and personal acquaintances'' of zoophiles who see their relationships over time tend to be less critical, and sometimes supportive. '']'' who study and understand animal behaviour and body language, have documented animal sexual advances to human beings and ], and tend to be matter-of-fact about animal sexuality and animal approaches to humans; their research is generally supportive of some of the claims by zoophiles regarding animal cognition, behaviour, and sexual/relational/emotional issues. Because the majority opinion is condemnatory, many individuals may be more accepting in private than they make clear to the public. Regardless, there is a clear consensus which regards zoophilia with either suspicion or outright opposition. | |||

| West Germany legalized bestiality in 1969<ref>{{cite news |title=Animal welfare: Germany moves to ban bestiality |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-20523950 |access-date=28 May 2021 |work=] |date=28 November 2012}}</ref> but banned it again in 2013.<ref>{{cite web |title=Tierschutzgesetz § 3 |url=https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/tierschg/__3.html |language=de |publisher=Bundesministerium der Justiz |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190129114917/https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/tierschg/__3.html |archive-date=29 January 2019 |url-status=live}}</ref> The 2013 law was unsuccessfully challenged before the ] in 2015.<ref>{{Cite press release |date=18 February 2016 |url=https://www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/DE/2016/bvg16-011.html |publisher=Bundesverfassungsgericht |language=de |title=Erfolglose Verfassungsbeschwerde gegen den Ordnungswidrigkeitentatbestand der sexuellen Handlung mit Tieren |website=www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de |access-date=26 February 2020 |trans-title=Unsuccessful constitutional complaint against the administrative offense of sexual acts with animals |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200129211855/https://www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/DE/2016/bvg16-011.html |archive-date=29 January 2020|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://apnews.com/5f6ffb7e5cd2472f9bc5b5e1f6cf8e37 |access-date=26 February 2020|title=Top German court rejects challenge to law against bestiality |date=18 February 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200129222233/https://apnews.com/5f6ffb7e5cd2472f9bc5b5e1f6cf8e37|archive-date=29 January 2020|url-status=live |website=AP NEWS}}</ref><ref>{{Cite magazine |url=https://time.com/4230863/germany-sex-animals/ |title=German Court Rules Sex With Animals Still Illegal |magazine=Time|access-date=26 February 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161229005235/http://time.com/4230863/germany-sex-animals/|archive-date=29 December 2016|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-35611906 |title=Bid to end German animal-sex ban fails |work=BBC News |date=19 February 2016 |access-date=26 February 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180131051614/http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-35611906 |archive-date=31 January 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.thelocal.de/20160218/top-court-throws-out-bid-to-legalize-bestiality |title=Top court throws out bid to legalize bestiality |newspaper=The Local Germany |date=18 February 2016 |access-date=29 January 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200129211847/https://www.thelocal.de/20160218/top-court-throws-out-bid-to-legalize-bestiality |archive-date=29 January 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref>{{Excessive citations inline|date=November 2021}} | |||

| <!-- Note for references: Animal sexual advances have been documented by ethologists such as ] and ] --> | |||

| Romania banned zoophilia in May 2022.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web |title=LEGE (A) 205 26/05/2004 - Portal Legislativ |url=https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/255132 |access-date=2024-01-18 |website=legislatie.just.ro}}</ref> | |||

| == Mythology and fantasy literature== | |||

| ] copulating with a goat; marble sculpture from the ancient city of ]]] | |||

| From cave paintings onward and throughout human history, zoophilia has been a recurring subject in art, literature, and fantasy. | |||

| Laws on bestiality are sometimes triggered by specific incidents.<ref>Howard Fischer: , | |||

| In ] mythology, the god ] is said to have impregnated a ] to sire a young bull god. In ], ] appeared to ] in the form of a ], and her children ] and ] resulted from that sexual union. Zeus also seduced ] in the form of a ], and carried off the youth ] in the form of an eagle. The half-human/half-bull ] was the offspring of Queen ] and a white bull. King ] continued to seduce the nymph ] despite her transforming into (among other forms) a lion, a bird, and a snake. The god ], often depicted with goat-like features, has also been frequently associated with animal sex. As with other subjects of ] mythology, some of these have been depicted over the centuries since, in western painting and sculpture. In ], ] had intercourse with a stallion and gave birth to ], see also ]. | |||

| ''Arizona Daily Star'', 28 March 2006. In Arizona, the motive for legislation was a "spate of recent cases."</ref> While some laws are very specific, others employ vague terms such as "]" or "bestiality", which lack legal precision and leave it unclear exactly which acts are covered. In the past, some bestiality laws may have been made in the belief that sex with another animal could result in monstrous offspring, as well as offending the community. Modern anti-cruelty laws focus more specifically on ] while anti-bestiality laws are aimed only at offenses to community "standards".<ref name="posner">Posner, Richard, A Guide to America's Sex Laws, The ], 1996. {{ISBN|978-0-226-67564-0}}. Page 207.</ref> | |||

| In Sweden, a 2005 report by the Swedish Animal Welfare Agency for the government expressed concern over the increase in reports of ] incidents. The agency believed animal cruelty legislation was not sufficient to protect animals from abuse and needed updating, but concluded that on balance it was not appropriate to call for a ban.<ref>{{cite web |title=Sweden highlights bestiality problem |date=29 Apr 2005 |website=TheLocal.se |url=http://www.thelocal.se/article.php?ID=1357 |access-date=13 May 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130515124451/http://www.thelocal.se/article.php?ID=1357 |archive-date=15 May 2013}}</ref> In New Zealand, the 1989 Crimes Bill considered abolishing bestiality as a criminal offense, and instead viewing it as a mental health issue, but they did not, and people can still be prosecuted for it. Under Section 143 of the Crimes Act 1961, individuals can serve a sentence of seven years duration for animal sexual abuse and the offence is considered 'complete' in the event of 'penetration'.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1961/0043/latest/DLM329260.html |title=Crimes Act 1961 No 43 (as at 01 October 2012), Public Act |publisher=New Zealand Legislation |date=1 October 2012 |access-date=4 January 2013}}</ref> | |||

| ] and the Bull'' by ], c. 1869]] | |||

| Fantasy literature has included a variety of seemingly zoophilic examples, often involving human characters enchanted into animal forms: '']'' (a young woman falls in love with a physically beast-like man), ]'s '']'' (Queen Titania falls in love with a character transformed into a donkey), '']'' (a princess champions a man enchanted into ape form), the ] ]'s '']'' (explicit sexuality between a man transformed into a donkey and a woman), and ]'s '']'' (a love affair between a soldier and a panther). In more modern times, zoosexuality of a sort has been a theme in science fiction and horror fiction, with the giant ape ] fixating on a human woman, alien monsters groping human females in pulp novels and comics, and depictions of ] in Japanese ] and ]. | |||

| As of 2023, bestiality is illegal in 49 U.S. states. Most state bestiality laws were enacted between 1999 and 2023.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Wisch |first=Rebecca F. |date=2022 |title=Table of State Animal Sexual Assault Laws |website=Animal Legal & Historical Center |url=https://www.animallaw.info/topic/table-state-animal-sexual-assault-laws |access-date=2022-09-30 |publisher=Michigan State University College of Law}}</ref> Bestiality remains legal in ], while 19 states have statutes that date to the 19th century or even the ]. The recent statutes are distinct from older sodomy statutes in that they define the proscribed acts with precision.<ref>{{cite magazine |url=https://newrepublic.com/amp/article/160448/meat-bestiality-artificial-insemination |title=The Meat Industry's Bestiality Problem |magazine=] |author1=Jan Dutkiewicz |author2=Gabriel N. Rosenberg |date=11 December 2020}}</ref> | |||

| Modern erotic ] fantasy art and stories are sometimes associated with zoophilia, but many creators and fans disagree with this, pointing out that the characters are predominantly humanoid fantasy creatures who are thinking, reasoning beings that consider and consent to sex in the same manner humans would. "Furry" characters have been compared to other intelligent and social non-human fictional characters who are subjects of love/sexuality fantasies without being commonly regarded as zoophilic, such as the ] and ]s in '']'', or ] in fantasy fiction. Animals and ], when shown in furry art are usually shown engaged with others of similar kind, rather than humans. | |||

| == |

=== Pornography === | ||

| {{Main|Obscenity|Legal status of Internet pornography}} | |||

| {{category see also|Animal pornography}} | |||

| {{more citations needed section|date=May 2021}} | |||

| ] | |||

| In the ], zoophilic pornography would be considered ] if it did not meet the standards of the ] and therefore is not openly sold, mailed, distributed or imported across state boundaries or within states which prohibit it. Under U.S. law, 'distribution' includes transmission across the Internet.{{Citation needed|date=November 2023}} The state of Oregon explicitly prohibits possession of media that depicts bestiality when such possession is for erotic purposes.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://oregon.public.law/statutes/ors_167.341| title=ORS 167.341 - Encouraging sexual assault of an animal | access-date=27 April 2024}}</ref> | |||

| Similar restrictions apply in ] (see ]). In ], the possession, making or distribution of material promoting bestiality is illegal.{{Citation needed|date=November 2023}} | |||

| Because of its controversial standing, different countries and medias vary in how they treat discussion of zoosexuality. Often sexual matters are the subject of legal or regulatory requirement. For example, in 2005, the UK broadcasting regulator (]) updated its code stating that: | |||

| :"Freedom of expression is at the heart of any democratic state. It is an essential right to hold opinions and receive and impart information and ideas. Broadcasting and freedom of expression are intrinsically linked. However, with such rights come duties and responsibilities ... The focus is on adult audiences making informed choices within a regulatory framework which gives them a reasonable expectation of what they will receive, while at the same time robustly protecting those too young to exercise fully informed choices for themselves ..." | |||