| Revision as of 22:11, 11 April 2010 editTrailfoot (talk | contribs)7 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:49, 7 January 2025 edit undoTonyTheTiger (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers401,272 edits →References: SA | ||

| (195 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Elongated mouth part}} | |||

| {{ |

{{About|the mouth part|the butterfly genus|Proboscis (genus){{!}}''Proboscis'' (genus)|the monkey|Proboscis monkey|anomaly of the human nose|Proboscis (anomaly)}} | ||

| ], two compound eyes, and a proboscis.]] | |||

| ] using its proboscis to reach the nectar of a flower]] | ] using its proboscis to reach the nectar of a flower]] | ||

| ] | |||

| A '''proboscis''' ({{IPAc-en|p|r|oʊ|ˈ|b|ɒ|s|ɪ|s|,_|-|k|ɪ|s}}) is an elongated appendage from the head of an animal, either a ] or an ]. In invertebrates, the term usually refers to tubular ] used for feeding and sucking. In vertebrates, a proboscis is an elongated nose or snout. | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| In general, a '''proboscis''' ({{IPA-en|proʊˈbɒsɪs}}; from ] προ, ''pro'' "before" and βοσκειν, ''boskein'' "to feed") is an elongated appendage from the head of an ], either a ] or an ].<ref name="Proboscis">{{cite web | url = http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/proboscis | title = proboscis | accessdate = 2008-07-27}}</ref> | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| First attested in English in 1609 from Latin {{lang|la|proboscis}}, the ] of the ] {{lang|grc|προβοσκίς}} ({{lang|grc-Latn|proboskis}}),<ref>, | |||

| Henry George Liddell, Robert S, ''A Greek–English Lexicon'', on Perseus Digital Library</ref> which comes from {{lang|grc|πρό}} ({{lang|grc-Latn|pro}}) 'forth, forward, before'<ref>, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, ''A Greek–English Lexicon'', on Perseus Digital Library</ref> + {{lang|grc|βόσκω}} ({{lang|grc-Latn|bosko}}), 'to feed, to nourish'.<ref>, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, ''A Greek–English Lexicon'', on Perseus Digital Library</ref><ref>{{OEtymD|proboscis}}</ref> The plural as derived from the Greek is {{lang|grc-Latn|proboscides}}, but in English the plural form ''proboscises'' occurs frequently. | |||

| The correct Greek plural is ''proboscides'', but in English it is more common to simply add ''-es'', forming ''proboscises''. | |||

| Although the word derives from the Greek "pro-boskein", the Latin spelling "proboscis" is taken in favor of the Greek "proboskis". | |||

| ==Invertebrates== | ==Invertebrates== | ||

| The most common usage is to refer to the tubular |

The most common usage is to refer to the tubular feeding and sucking organ of certain invertebrates such as insects (e.g., ], and mosquitoes), worms (including ], ]) and ] ]s. | ||

| ===Acanthocephala=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The ], the thorny-headed worms or spiny-headed worms, are characterized by the presence of an eversible proboscis, armed with spines, which they use to pierce and hold the ] wall of their host. | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| ===Lepidoptera mouth parts=== | ===Lepidoptera mouth parts=== | ||

| The mouth parts of Lepidoptera mainly consist of the sucking kind; this part is known as the ] or 'haustellum'.The proboscis consists of two tubes held together by hooks and separable for cleaning. The proboscis contains muscles for operating. Each tube is inardly concave, thus forming a central tube up which moisture is sucked. Suction takes place due to the contraction and expansion of a sac in the head.<ref name="Evans">Evans, Identification of Indian Butterflies'', Introduction, pp 1 to 35.</ref> | |||

| ] ('']'') feeding with extended proboscis]] | |||

| ⚫ | A few Lepidoptera species lack mouth parts and therefore do not feed in the ]. Others, such as the family ], have mouth parts of the chewing kind.<ref name=tj>Charles A. Triplehorn and Norman F. Johnson (2005). |

||

| The mouth parts of ] (] and ]s) mainly consist of the sucking kind; this part is known as the proboscis or 'haustellum'. The proboscis consists of two tubes held together by hooks and separable for cleaning. The proboscis contains muscles for operating. Each tube is inwardly concave, thus forming a central tube up which moisture is sucked. Suction takes place due to the contraction and expansion of a sac in the head.<ref name="Evans">Evans, W. H. (1927) , The Diocesan press. Introduction, pp. 1–35.</ref> A specific example of the proboscis being used for feeding is in the species '']''. In this species, the moth hovers in front of the flower and extends its long proboscis to attain its food.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ysJZBhHe8IcC&q=deilephila+elpenor+behavior&pg=PA85|title=From Animals to Animats 7: Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Simulation of Adaptive Behavior|last1=Hallam|first1=Bridget|last2=Floreano|first2=Dario|last3=Hallam|first3=John|last4=Hayes|first4=Gillian|last5=Meyer|first5=Jean-Arcady|date=2002|publisher=MIT Press|isbn=9780262582179|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | A few Lepidoptera species lack mouth parts and therefore do not feed in the ]. Others, such as the family ], have mouth parts of the chewing kind.<ref name=tj>Charles A. Triplehorn and Norman F. Johnson (2005). ''Borror and Delong's Introduction to the Study of Insects'' (7th edition). Thomson Brooks/Cole, Belmont, CA. {{ISBN|0-03-096835-6}}</ref> | ||

| The study of insect mouthparts was helpful for the understanding of the functional mechanism of the proboscis of ] (Lepidoptera) to elucidate the evolution of new form-function.<ref name="Krenn-2000-2">{{cite journal|vauthors=Krenn HW, Kristensen NP |year=2000|title=Early evolution of the proboscis of Lepidoptera: external morphology of the galea in basal glossatan moths, with remarks on the origin of the pilifers|journal=Zoologischer Anzeiger |volume=239|pages= 179–196}}</ref><ref name="Krenn-2004">{{cite journal|vauthors=Krenn HW, Kristensen NP |year=2004|title= Evolution of proboscis musculature in Lepidoptera|journal= European Journal of Entomology |volume=101|issue=4|pages= 565–575|doi=10.14411/eje.2004.080|doi-access=free|s2cid=54538516 |url=http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/995a/3e78385f79d354a601ac1ff9b6a09fd56086.pdf}}</ref> The study of the proboscis of butterflies revealed surprising examples of adaptations to different kinds of fluid food, including ], ], tree sap, dung<ref name="Krenn-2001">{{cite journal|title=Proboscis morphology and food preferences in Nymphalidae (Lepidoptera, Papilionoidea)|journal=J. Zool. Lond.|year= 2001|volume=253|pages=17–26|vauthors=Krenn HW, Zulka KP, Gatschnegg T |doi=10.1017/S0952836901000528}}</ref><ref name="Krenn-2003">{{cite journal|title=Efficiency of fruit juice feeding in ''Morpho peleides'' (Nymphalidae, Lepidoptera)|journal=Journal of Insect Behavior|volume=16|pages=67–77|doi=10.1023/A:1022849312195|year=2003|last1=Knopp|first1=M. C. N.|last2=Krenn|first2=H. W.|issue=1 |bibcode=2003JIBeh..16...67K |s2cid=33428687}}</ref><ref name="Krenn-2010">{{cite journal|doi=10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085338|pmid=19961330|pmc=4040413|title=Feeding Mechanisms of Adult Lepidoptera: Structure, Function, and Evolution of the Mouthparts|journal=Annual Review of Entomology|volume=55|pages=307–27|year=2010|last1=Krenn|first1=Harald W.}}</ref> and of adaptations to the use of ] as complementary food in '']'' butterflies.<ref name="Krenn-2009">{{cite journal|title=Mechanical damage to pollen aids nutrient acquisition in ''Heliconius'' butterflies (Nymphalidae)|journal=Arthropod-Plant Interactions|volume=3|issue=4|pages=203–208|doi=10.1007/s11829-009-9074-7|pmid=24900162|year=2009|last1=Krenn|first1=Harald W.|last2=Eberhard|first2=Monika J. B.|last3=Eberhard|first3=Stefan H.|last4=Hikl|first4=Anna-Laetitia|last5=Huber|first5=Werner|last6=Gilbert|first6=Lawrence E.|authorlink6=Lawrence E. Gilbert|pmc=4040415|bibcode=2009APInt...3..203K }}</ref><ref name="2011-2">{{cite journal|pmid=22208893|pmc=3281465|title=Pollen processing behavior of ''Heliconius'' butterflies: A derived grooming behavior|journal=Journal of Insect Science|volume=11|issue=99|pages=99|year=2011|last1=Hikl|first1=A. L.|last2=Krenn|first2=H. W.|doi=10.1673/031.011.9901}}</ref> An extremely long proboscis appears within different groups of flower-visiting insects, but is relatively rare. | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| === Gastropods === | |||

| {{expand section|date=August 2023|with=more information, examples, and links.}} | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| |align=right | |||

| |total_width=375 | |||

| |image1=Mitra-mitra.jpg | |||

| ⚫ | |caption1=Proboscis of a predatory marine snail '']''. | ||

| |image2=Kelletia kelletii 4.jpg | |||

| |caption2=] feeding on a dead fish using a long, prehensile proboscis.}} | |||

| Some ] of ]s have evolved a proboscis. In gastropods, the proboscis is an elongation of the snout with the ability to retract inside the body; it can be used for feeding, sensing the environment, and in some cases, capturing prey or attaching to hosts. Three major types of proboscises have been identified: pleurembolic (partially retractable), acrembolic (fully retractable), and intraembolic (variable in structure). Acrembolic proboscises are usually found in ] gastropods.<ref>{{cite journal|journal=Malacopedia|issn=2595-9913|edition=Volume 2(4): 22–29|last=Simone|first=Luiz|date=September 2019|title=The proboscis of the Gastropoda 1: its evolution|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336014299}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|journal=Journal of Molluscan Studies|author=Ball, A.D. and Andrews, E.B. and Taylor, J.D.|title=THE ONTOGENY OF THE PLEUREMBOLIC PROBOSCIS IN ''NUCELLA LAPILLUS'' (GASTROPODA: MURICIDAE) |volume=63|number=1|pages=87–89|date=1997-02-01|doi=10.1093/mollus/63.1.87 |issn=0260-1230|url=https://academic.oup.com/mollus/article-pdf/63/1/87/3011806/63-1-87.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| ==Vertebrates== | ==Vertebrates== | ||

| ⚫ | The |

||

| ] | |||

| The ] is named for its enormous nose, and an elongated human ] is sometimes facetiously called a proboscis. | |||

| ⚫ | The elephant's trunk and the ]'s elongated nose are called "proboscis", as is the snout of the male ]. | ||

| An abnormal facial appendage that sometimes accompanies ocular and nasal abnormalities in humans is also called a proboscis. | |||

| Notable mammals with some form of proboscis are: | Notable mammals with some form of proboscis are: | ||

| * Members of the ] family (see ]). | |||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] |

* ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * '']'' (extinct) | |||

| ⚫ | * '']'' (extinct) | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * Members of the ] family | |||

| The ] is named for its enormous nose. | |||

| The human nose is sometimes called a proboscis, especially when large or prominent. | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * {{annotated link|Beak}} | |||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * {{annotated link|Nostril}} | |||

| * {{annotated link|Rostrum (anatomy) }} | |||

| * {{annotated link|Snout}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| ⚫ | {{Reflist|30em}} | ||

| * http://stuartgibson.aminus3.com/image/2007-09-07.html | |||

| ⚫ | {{Reflist}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| {{animal-stub}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 22:49, 7 January 2025

Elongated mouth part This article is about the mouth part. For the butterfly genus, see Proboscis (genus). For the monkey, see Proboscis monkey. For anomaly of the human nose, see Proboscis (anomaly).

A proboscis (/proʊˈbɒsɪs, -kɪs/) is an elongated appendage from the head of an animal, either a vertebrate or an invertebrate. In invertebrates, the term usually refers to tubular mouthparts used for feeding and sucking. In vertebrates, a proboscis is an elongated nose or snout.

Etymology

First attested in English in 1609 from Latin proboscis, the latinisation of the Ancient Greek προβοσκίς (proboskis), which comes from πρό (pro) 'forth, forward, before' + βόσκω (bosko), 'to feed, to nourish'. The plural as derived from the Greek is proboscides, but in English the plural form proboscises occurs frequently.

Invertebrates

The most common usage is to refer to the tubular feeding and sucking organ of certain invertebrates such as insects (e.g., moths, butterflies, and mosquitoes), worms (including Acanthocephala, proboscis worms) and gastropod molluscs.

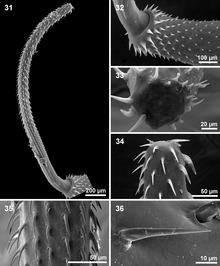

Acanthocephala

The Acanthocephala, the thorny-headed worms or spiny-headed worms, are characterized by the presence of an eversible proboscis, armed with spines, which they use to pierce and hold the gut wall of their host.

Lepidoptera mouth parts

The mouth parts of Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) mainly consist of the sucking kind; this part is known as the proboscis or 'haustellum'. The proboscis consists of two tubes held together by hooks and separable for cleaning. The proboscis contains muscles for operating. Each tube is inwardly concave, thus forming a central tube up which moisture is sucked. Suction takes place due to the contraction and expansion of a sac in the head. A specific example of the proboscis being used for feeding is in the species Deilephila elpenor. In this species, the moth hovers in front of the flower and extends its long proboscis to attain its food.

A few Lepidoptera species lack mouth parts and therefore do not feed in the imago. Others, such as the family Micropterigidae, have mouth parts of the chewing kind.

The study of insect mouthparts was helpful for the understanding of the functional mechanism of the proboscis of butterflies (Lepidoptera) to elucidate the evolution of new form-function. The study of the proboscis of butterflies revealed surprising examples of adaptations to different kinds of fluid food, including nectar, plant sap, tree sap, dung and of adaptations to the use of pollen as complementary food in Heliconius butterflies. An extremely long proboscis appears within different groups of flower-visiting insects, but is relatively rare.

Gastropods

| This section needs expansion with: more information, examples, and links.. You can help by adding to it. (August 2023) |

Proboscis of a predatory marine snail Mitra mitra.

Proboscis of a predatory marine snail Mitra mitra. Kellet's whelks feeding on a dead fish using a long, prehensile proboscis.

Kellet's whelks feeding on a dead fish using a long, prehensile proboscis.

Some evolutionary lineages of gastropods have evolved a proboscis. In gastropods, the proboscis is an elongation of the snout with the ability to retract inside the body; it can be used for feeding, sensing the environment, and in some cases, capturing prey or attaching to hosts. Three major types of proboscises have been identified: pleurembolic (partially retractable), acrembolic (fully retractable), and intraembolic (variable in structure). Acrembolic proboscises are usually found in parasitic gastropods.

Vertebrates

The elephant's trunk and the tapir's elongated nose are called "proboscis", as is the snout of the male elephant seal.

Notable mammals with some form of proboscis are:

- Aardvark

- Anteater

- Elephant

- Elephant shrew

- Hispaniolan solenodon

- Echidna

- Elephant seal

- Leptictidium (extinct)

- Moeritherium (extinct)

- Numbat

- Proboscis monkey

- Saiga antelope

- Members of the tapir family

The proboscis monkey is named for its enormous nose.

The human nose is sometimes called a proboscis, especially when large or prominent.

See also

- Beak – Part of a bird

- Nostril – Nose orifice that enables the entry and exit of air.

- Rostrum (anatomy) – Anatomy term

- Snout – Extended part of an animal's mouth

References

- προβοσκίς, Henry George Liddell, Robert S, A Greek–English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- πρό, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- βόσκω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- Harper, Douglas. "proboscis". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Amin OA, Heckmann RA, Ha NV (2014). "Acanthocephalans from fishes and amphibians in Vietnam, with descriptions of five new species". Parasite. 21: 53. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014052. PMC 4204126. PMID 25331738. Art. No. 53.

- Evans, W. H. (1927) Identification of Indian Butterflies, The Diocesan press. Introduction, pp. 1–35.

- Hallam, Bridget; Floreano, Dario; Hallam, John; Hayes, Gillian; Meyer, Jean-Arcady (2002). From Animals to Animats 7: Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Simulation of Adaptive Behavior. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262582179.

- Charles A. Triplehorn and Norman F. Johnson (2005). Borror and Delong's Introduction to the Study of Insects (7th edition). Thomson Brooks/Cole, Belmont, CA. ISBN 0-03-096835-6

- Krenn HW, Kristensen NP (2000). "Early evolution of the proboscis of Lepidoptera: external morphology of the galea in basal glossatan moths, with remarks on the origin of the pilifers". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 239: 179–196.

- Krenn HW, Kristensen NP (2004). "Evolution of proboscis musculature in Lepidoptera" (PDF). European Journal of Entomology. 101 (4): 565–575. doi:10.14411/eje.2004.080. S2CID 54538516.

- Krenn HW, Zulka KP, Gatschnegg T (2001). "Proboscis morphology and food preferences in Nymphalidae (Lepidoptera, Papilionoidea)". J. Zool. Lond. 253: 17–26. doi:10.1017/S0952836901000528.

- Knopp, M. C. N.; Krenn, H. W. (2003). "Efficiency of fruit juice feeding in Morpho peleides (Nymphalidae, Lepidoptera)". Journal of Insect Behavior. 16 (1): 67–77. Bibcode:2003JIBeh..16...67K. doi:10.1023/A:1022849312195. S2CID 33428687.

- Krenn, Harald W. (2010). "Feeding Mechanisms of Adult Lepidoptera: Structure, Function, and Evolution of the Mouthparts". Annual Review of Entomology. 55: 307–27. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085338. PMC 4040413. PMID 19961330.

- Krenn, Harald W.; Eberhard, Monika J. B.; Eberhard, Stefan H.; Hikl, Anna-Laetitia; Huber, Werner; Gilbert, Lawrence E. (2009). "Mechanical damage to pollen aids nutrient acquisition in Heliconius butterflies (Nymphalidae)". Arthropod-Plant Interactions. 3 (4): 203–208. Bibcode:2009APInt...3..203K. doi:10.1007/s11829-009-9074-7. PMC 4040415. PMID 24900162.

- Hikl, A. L.; Krenn, H. W. (2011). "Pollen processing behavior of Heliconius butterflies: A derived grooming behavior". Journal of Insect Science. 11 (99): 99. doi:10.1673/031.011.9901. PMC 3281465. PMID 22208893.

- Simone, Luiz (September 2019). "The proboscis of the Gastropoda 1: its evolution". Malacopedia (Volume 2(4): 22–29 ed.). ISSN 2595-9913.

- Ball, A.D. and Andrews, E.B. and Taylor, J.D. (1997-02-01). "THE ONTOGENY OF THE PLEUREMBOLIC PROBOSCIS IN NUCELLA LAPILLUS (GASTROPODA: MURICIDAE)" (PDF). Journal of Molluscan Studies. 63 (1): 87–89. doi:10.1093/mollus/63.1.87. ISSN 0260-1230.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)